Abstract

Background and Purpose

The effects of 4-O-methylhonokiol (MH), a constituent of Magnolia officinalis, were investigated on human prostate cancer cells and its mechanism of action elucidated.

Experimental Approach

The anti-cancer effects of MH were examined in prostate cancer and normal cells. The effects were validated in vivo using a mouse xenograft model.

Key Results

MH increased the expression of PPARγ in prostate PC-3 and LNCap cells. The pull-down assay and molecular docking study indicated that MH directly binds to PPARγ. MH also increased transcriptional activity of PPARγ but decreased NF-κB activity. MH inhibited the growth of human prostate cancer cells, an effect attenuated by the PPARγ antagonist GW9662. MH induced apoptotic cell death and this was related to G0-G1 phase cell cycle arrest. MH increased the expression of the cell cycle regulator p21, and apoptotic proteins, whereas it decreased phosphorylation of Rb and anti-apoptotic proteins. Transfection of PC3 cells with p21 siRNA or a p21 mutant plasmid on the cyclin D1/ cycline-dependent kinase 4 binding site abolished the effects of MH on cell growth, cell viability and related protein expression. In the animal studies, MH inhibited tumour growth, NF-κB activity and expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, whereas it increased the transcriptional activity and expression of PPARγ, and the expression of apoptotic proteins and p21 in tumour tissues.

Conclusions and Implication

MH inhibits growth of human prostate cancer cells through activation of PPARγ, suppression of NF-κB and arrest of the cell cycle. Thus, MH might be a useful tool for treatment of prostate cancer.

Keywords: 4-O-methylhonokiol, PPAR-γ, NF-κB, p21, cancer cells, growth inhibition

Introduction

The root and stem bark of Magnolia officinalis are used in oriental medicine and this medicinal herb and its bioactive constituents, such as honokiol, obovatol and magnolol, have been shown to exhibit a variety of biological actions, including anti-tumour, anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic and anxiolytic effects (Lee et al., 2011). Several studies have shown that honokiol has anti-angiogenic, anti-proliferative and anti-invasive activities in colon and prostate cancer cells as well as in lung, breast and ovarian cancer cells (Yang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; Wolf et al., 2007; Hahm et al., 2008; Fried and Arbiser, 2009). Magnolol has also been shown to induce apoptosis and suppress the proliferation of cancer cells, and inhibit tumour metastasis in various cancer cells, including those of the colon and prostate (Lin et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2009). Further, we recently found that obovatol also inhibits colon and prostate cancer cell growth (Lee et al., 2008).

PPARs are members of the nuclear hormone-receptor superfamily of ligand-dependent transcriptional factors and have three major subtypes (α, β and γ). PPARs have been demonstrated to have a number of pathophysiological roles and there is mounting evidence suggesting that PPARγ is important in the control of cancer cell growth (Kim et al., 2003). PPARγ is up-regulated in many malignant tissues and PPARγ ligands induce terminal differentiation, cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in a variety of cancer cells including those of the prostate (Haydon et al., 2002; Yamakawa-Karakida et al., 2002). PPARγ negatively regulates gene expression of cell proliferation and pro-apoptotic genes in a ligand-dependent manner by antagonizing the activities of NF-κB in prostate cancer cells (Hirsch et al., 2011). Cell-cycle regulatory proteins, such as p21, have been shown to play a critical role in the PPARγ-induced inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth (Radhakrishnan and Gartel, 2005). Moreover, the well-known PPARγ agonist, 15-deoxy-PGJ2 and other activators induce inhibitory effects on cancer cell growth in a PPARγ-dependent manner through inactivation of NF-κB (Kim et al., 2003; Papineni et al., 2008).

NF-κB is a transcription factor regulating various genes involved in the production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules and growth factors (Richmond, 2002). NF-κB mediates tumour promotion and progression, angiogenesis, metastasis of cancer cells and promotes resistance to various chemotherapeutics by increasing the expression of genes participating in cancer development (Pikarsky et al., 2004; Dolcet et al., 2005). NF-κB also regulates the expression of a number of anti-apoptotic proteins and apoptotic genes as well as proliferation genes (Wang et al., 1998). Interestingly, NF-κB is constitutively activated in various solid tumours including animal and human prostate tumours (Lind et al., 2001; Suh and Rabson, 2004). Constitutive activation of NF-κB has been found to up-regulate the expression of anti-apoptotic and proliferation genes, and therefore, disrupt the balance between apoptosis and proliferation leading to cancer cell growth (Garg and Aggarwal, 2002). Thus, inhibition of NF-κB has been presented as a key regulator of cell growth of various cancer cells (Lee et al., 2002; Allen et al., 2007). We have also demonstrated that suppression of NF-κB by naturally occurring compounds, such as inflexinol, thiacremonone and cobra toxin, inhibits colon and prostate cancer cell growth (Son et al., 2007; Ban et al., 2009a; 2009b).

Functional inactivation of the p21 pathway has been observed in most human tumours (Biggs and Kraft, 1995) and p21 is an important cellular checkpoint protein for the inhibition of cell growth through the control of cyclin-cycline-dependent kinases (CDKs) activities in human cancer cells (Ivanovska et al., 2008). NF-κB and PPARγ are also important in p21-mediated cell cycle arrest of human cancer cells (Hellin et al., 2000; Prakobwong et al., 2011); the expression of p21 is increased in the resistant human cancer cells in a NF–κB- and PPARγ-dependent manner (Chang and Miyamoto, 2006; Jarvis et al., 2005). Moreover, many investigators, using components and crude extracts isolated from the Magnolia family, have shown that p21-mediated cell cycle arrest leads to cell growth inhibition (Hahm and Singh, 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009). We recently isolated a bioactive compound, 4-O-methylhonokiol (MH) from M. officinalis, and found it suppressed NF-κB activity in macrophages and colon cancer cells (Oh et al., 2009; 2012). The growth inhibitory effects of the bioactive constituents of M. officinalis, obovatol, honokiol and magnolol, are thought to be associated with the inhibitory ability of these compounds on NF-κB activity in cancer cells (Lee et al., 2007; 2008). In addition, we recently found that MH-induced inhibition of colon tumour growth was accompanied by a suppression of NF-κB activity (Oh et al., 2012).

Thus, we hypothesized that MH inhibits the growth of human prostate cancer cells through activation of PPARγ and inactivation of NF-κB, and these effects are mediated by the induction of p21. Here, we showed that MH enhances PPARγ activity but decreases NF-κB activity, and thus inhibits prostate cancer cell growth through induction of p21.

Methods

Reagents

MH (Supporting Information Figure S1A) was isolated from the bark of M. officinalis Rehd. et Wils, by subsequently extracting with n-hexane, ethyl acetate and n-BuOH, and then identified by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR as described elsewhere (Oh et al., 2009). MH was supplied by Bioland Ltd. (Chungnam, Korea) as a brown oilish solution of 99.6% purity. The stock solution of MH was diluted in 0.05% DMSO (final concentration, 50 mM).

Cell culture

PC-3, LNCaP human prostate cancer and PWR-1E human prostate normal cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The PC-3 (11 passages) and LNCap (43 passages) prostate cancer cells were grown in RPMI1640, and the CCD 112-CoN cells were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium with 10% FBS, 100 U·mL−1 penicillin, and 100 μg·mL−1 streptomycin. The PWR-1E cells were cultured in a keratinocyte growth medium supplemented with 5 ng·mL−1 human recombinant EGF and 0.05 mg·mL−1 bovine pituitary extract (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Cell growth assay

Cells (5 × 104 cells per well) were plated onto 24-well plates. The cell growth inhibitory effect of MH was evaluated in cells treated with MH (0–30 μM) for 0–72 h, using an excluded trypan blue assay.

Transfection and assay of luciferase activity

Cells (1 × 105 cells per well) were plated in 24-well plates and transiently transfected with pNF-κB-Luc plasmid (5× NF-κB; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) or plasmid pFA-GAL4-PPARγ, using a mixture of plasmid and lipofectamine PLUS in OPTI-MEN according to manufacturer's specification (Invitrogen). The transfected cells were treated with MH in the absence (for assay of PPARγ activity) or presence (for assay of NF-κB activity) of TNF-α (10 ng·mL−1) for 8 h. To induce NF-κB luciferase activity, we co-treated the cells with TNF-α (10 ng·mL−1). Luciferase activity was measured by using the luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI).

Electromobility shift assay

Electromobility shift assay was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Promega) as described elsewhere (Oh et al., 2009).

Western blot analysis

Protein (40 μg) from cultured cells was separated on a SDS/12%-polyacrylamide gel, and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were then immunoblotted with primary specific antibodies: rabbit polyclonal antibodies for PPARγ, p65, bax, bcl-2, GSK-3β (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Santa Cruz, CA, USA), caspase-3, caspase-9, pp53, survivin, c-IAP1 (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Beverly, MA), and cIAP2 (1:1000 dilution, Abcam Ltd., Cambridge, UK) and mouse monoclonal antibodies for p50, p53, CDK6 (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), CDK4, p21, cyclin D, cyclin E (1:1000 dilution, Medical and Biology Laboratories Co. Ltd., Nagoya, Japan), iNOS and COX-2 (1:1000 dilution, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The blot was then incubated with the corresponding conjugated anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:2000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.).

Cell-cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Subconfluent cells were treated with MH (0–30 μM) in culture medium for 0–72 h. The analysis methods are as described elsewhere (Ban et al., 2009a).

Transfection of siRNA and p21 mutant plasmid

Cells were transfected with 100 nM of CDKN1A (p21), NF-κB (p50 or 65) siRNA or non-specific siRNA (Bioneer, Co., Daejon, Korea) and p21 mutant plasmid (CDKN1A p21, obtained from Dr Anindya Dutta, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA, USA), which has mutated cyclin D1/CDK4 complex binding site (Cy1 site, △17–24) using WelFect-EX plus transfection reagent (WelGENE, Seoul, Korea) prepared in a serum-free culture medium at 37°C (Hsu et al., 2007). After 6 h, a complete medium was added and the cells were further cultured for 24 h.

Detection of apoptosis

Cells (1 × 104 cells per well) were cultured in 8-well chamber slides (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) for 24 h. The method used to detect apoptotic cell death was as described elsewhere (Ban et al., 2009b). The apoptotic index was determined as the number of DAPI-stained TUNEL-positive stained cells divided by the total number of cells counted × 100.

Pull-down assays

MH bead conjugation was prepared and a pull-down assay conducted as described previously (Shim et al., 2008). MH was conjugated with cyanogen bromide (CNBr)-activated Sepharose 4B (Sigma Chemical Co.). Briefly, MH (1 mg) was dissolved in 500 μL of coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 6.0). The CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B was swelled and washed with 1 mM HCl, then washed with the coupling buffer. CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads were added to the MH-containing coupling buffer and incubated at 4°C for 24 h. The MH-conjugated Sepharose 4B was washed with three cycles of alternating pH wash buffers (buffer 1, 0.1 M acetate and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.0; buffer 2, 0.1 M Tris-HCl and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.0). MH-conjugated beads were then equilibrated with binding buffer (0.05 M Tris-HCl and 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.5). The control unconjugated CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads were prepared as described earlier in the absence of MH. For the pull-down assay, PPARγ proteins (Abcam Ltd.) or cell lysate from PC-3 prostate cancer cells were incubated with MH-Sepharose 4B beads in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, 2 μg·mL−1 BSA, 0.02 mM PMSF, 1 × proteinase inhibitor). The beads were washed five times with buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, 0.02 mM PMSF), and proteins bound to the beads were analysed by immunoblotting with the PPARγ antibodies or cell lysates.

Molecular modelling

The dimeric structure of PPARγ complexed with nitrated fatty acids LNO2 with 2.4 Å resolution (PDB ID: 3CWD) (Cheng et al., 2009) was selected for docking with MH and only half of it was used for the study. For MH, rotational flexibility was allowed for all ligand backbone bonds. The initial search with the VINA docking calculation was done at the binding pocket where the LNO2 ligand binds. Then, to get a better sampling of all possible binding sites on the PPARγ, the search was expanded to include one monomer of the PPARγ protein. The grid box was centred on the PPARγ monomer and the size of the grid box was adjusted to completely include the whole PPARγ monomer. All bonds able to be rotated on the MH were allowed to rotate during the molecular simulation. Docking experiments were performed at various exhaustive values of the default value, 25, 50 and 100. All these experiments identified the binding site with the highest affinity at the same binding pocket with essentially identical binding conformation on the MH backbone.

Antitumour activity study in in vivo xenograft animal model

Six-week-old male BALB/c athymic nude mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan). All experiments were approved and carried out according to the Guideline for ‘Care and Use of Animals' of the Chungbuk National University Animal Care Committee. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). SW620 and PC3 cells were injected s.c. (1 × 107 cells in 0.1 mL PBS per animal) into the lower right flanks of mice. After 20 days, when the tumours had reached an average volume of 300–400 mm3 or about 50 mm3 (for prostate), the tumour-bearing nude mice were i.p. injected with MH (40 and 80 mg·kg−1 dissolved in 0.1% DMSO) twice per week for 3 weeks. Cisplatin (10 mg·kg−1, Choongwae Pharma Co., Seoul, Korea) was also i.p. injected once a week as a positive control. The group treated with 0.1% DMSO was designated as the control. The tumour volumes were measured with vernier calipers and calculated by the following formula: (A × B2)/2, where A is the larger and B is the smaller of the two dimensions.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described elsewhere (Ban et al., 2009a) with 5 μm thick tissue sections using primary mouse PCNA, PPARγ, Ki-67 and p65 (1:200 dilution) antibodies or primary rabbit p50 and cleaved caspase-3 antibody (1:100 dilution) followed by a secondary biotinylated anti-mouse or rabbit antibody. For quantification, 200 cells at three randomly selected areas were assessed, and the positively stained cells were counted and are expressed as a percentage of stained cells.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 4 software (Version 4.03, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were assessed by one-way anova. If the P-value in the anova test was significant, the differences (P < 0.05) between the pair of means were assessed by Dunnet's test. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments with triplicates.

Results

MH increased the expression, transcription and DNA binding activities, and nuclear translocation of PPARγ

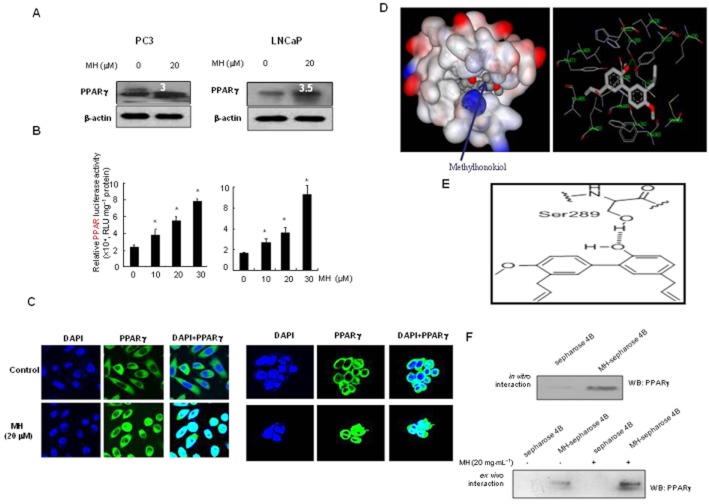

To investigate whether the inhibitory effect of MH on cell growth is dependent on PPARγ, the expression of PPARγ was first determined in two prostate cancer cells. The expression of PPARγ was easily detected in the untreated cells was increased (3- or 3.5-fold increase) after MH treatment (20 μM) in both cells (Figure 1A). To investigate whether MH is able to activate PPARγ-dependent transcription in these cells, the functional status of endogenous PPARγ was determined using a luciferase reporter assay system. MH significantly increased PPARγ transcription activity, in a concentration-dependent manner, in cells transiently transfected with the PPARγ construct (Figure 1B). The other related compounds isolated from M. officinalis had a similar effect on PPARγ transcription activity that was about 90% of that induced by a well-known PPAR-γ agonist, 15-deoxy-PGJ2, determined in PC3 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S1B). We also performed a gel mobility shift assay to assess whether MH increased the DNA binding activity of PPARγ. The DNA binding activity of PPARγ in untreated cells was not significant, but a substantial increase of binding activity was observed in the cells treated with MH and other compounds isolated from M. officinalis (Figure 1B). This binding activity was inhibited in the presence of cold PPAR response element (PPRE) oligonucleotides, but not in unrelated labelled PPRE oligonucleotides and the DNA-binding complex was supershifted by anti-PPARγ (data not shown). MH caused nuclear translocation of PPARγ, which is localized predominantly in the perinuclear region and cytoplasms in the untreated cells (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Expression of PPARγ in prostate PC-3 and LNCap cells. (A) Cells were treated with 20 μM MH for 24 h. Whole cell extracts were prepared and PPARγ expression was determined by Western blot analysis as described in Methods. The value above the band indicates fold increase of PPARγ expression. (B) Transcriptional activation determined by luciferase activity. Luciferase activity was determined in the cells transfected with PPARγ plasmid construct after treatment with MH for 24 h as described in Methods. Values are mean ± SD of three experiments, with triplicate results for each experiment. (C) Immunoreactivity of PPARγ in PC-3 cells and in LNCaP cells treated with 20 μM MH. Untreated cells showed that PPARγ was localized predominantly in the perinuclear region and cytoplasm. Cells treated with MH demonstrated nuclear translocation of PPARγ. D-(a), Representations of the interaction between PPARγ and MH. MH binds to a tight-binding cavity within the agonist binding pocket in the ligand-binding domain of PPARγ shown in surface model. D-(b), The surrounding peptide residues that interact with MH are shown in the second picture. (E) Hydrogen-bonding interaction between hydroxyl group of MH and hydroxyl side chain of Ser289 of PPARγ. (F) MH-Sepharose 4B was used to pull down with PPARγ protein (Abcam Ltd.). WB, Western blot.

In the molecular docking experiment, MH was predicted to bind at the identical ligand binding site as other PPARγ agonists, such as 15-deoxy-PGJ2 (Waku et al., 2009) and the fatty acid ligand LNO2 (Cheng et al., 2009). This implies that MH may activate PPARγ in the same manner as 15-deoxy-PGJ2 and other PPARγ agonists. According to the binding model, MH also forms hydrophobic interactions with Phe282, Cys285, Ile326, Tyr327, Leu330, Phe363, Met364, Leu453, Leu465 and Leu469 (Figure 1D). One hydrogen bond was observed between the hydroxyl group of the MH and the hydroxyl side chain of Ser289 in PPARγ (Figure 1E). The interaction was thus assessed in a pull-down assay using MH-sepharose 4B beads. The binding of MH to PPARγ was then detected by immunoblotting with anti-PPARγ in in vitro and ex vivo tests and MH was found to bind with recombinant PPARγ protein (Figure 1F).

MH inhibited cancer cell growth, caused G0/G1 phase arrest and induced apoptotic cell death, and PPARγ antagonist reversed the effects of MH

We then investigated whether PPARγ activation resulted in cell growth inhibition. MH (0–30 μM) treatment resulted in a significant concentration- and time-dependent inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth (Figure 2A). However, MH was not cytotoxic in the normal prostate PWR-1E cells at the concentrations tested (Figure 1C). Even though it was clear that the the LNCaP grew much faster than the PC-3 cells, in contrast to previous observations (Horoszewicz et al., 1983; Lin et al., 1998), it is noteworthy that the doubling times of these two cells are similar (Yu et al., 2008), and the doubling time of LNCaP (androgen dependent cells) can be easily changed by the culture condition such as concentration of serum, and presence of other hormones and status of specific genes carrying as demonstrated by Horoszewicz et al. (1983) and Ghosh et al. (2006). We next measured apoptotic cell death, to determine whether MH-induced cell growth inhibition was due to apoptotic cell death. Apoptotic cell numbers were increased to 3 ± 5, 10 ± 6, 30 ± 20 and 75 ± 2% in PC3 cells, and 0 ± 6, 6 ± 2, 50 ± 6 and 63 ± 2% in LNCaP cells by 0–30 μM MH, respectively (Figure 2B). To further study the involvement of PPARγ in the MH-induced cell growth inhibition and induction of apoptotic cell death, we employed the PPARγ antagonist SW9662 (0–30 μM). Pretreating cells with SW9662 30 min before incubating them with MH for 72 h reversed MH-induced cell growth inhibition in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C), and also reversed the induction of apoptotic cell death (Figure 2D). To determine whether the apoptotic cell death resulted from cell cycle arrest, we examined cell cycle arrest for 72 h. Exposure of cells to MH (0–30 μM) increased the number of prostate cancer cells in the G0/G1 fraction in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Figure 3A).

Figure 2.

Effect of MH and WS9662 on cancer cell growth and apoptotic cell death. (A and C) Cells were treated with 0–30 μM MH for different times (0–72 h) (A) or treated with SW9662 for 72 h (C). Cell counting was performed as described in Methods. (B and D) Cells were treated with 0–30 μM MH for 24 h or the cells were pretreated with SW9662 for 24 h. DAPI and TUNEL staining were performed as described in Methods. Columns, mean of triplicate; bars, SD. *P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the untreated group. #P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the MH treated group.

Figure 3.

Effect of MH on cell cycle, and expression of proteins regulating cell growth, cell cycle and apoptotic cell death, and NF-κB DNA binding, transcriptional activity and translocation of p50 and p65. (A) Cells were treated with 0–30 μM MH for 72 h. Cell cycle was performed as described in Methods. (B and C) Cells were treated with 0–30 μM MH for 24 h, and used for Western blotting as described in Methods. The blots were representative of three experiments. (D and F) Cells were treated with 0–30 μM MH for 1 h. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (D) and immunofluorescence (F) were performed as described in Methods. Numbers, fold activation in relation to the control (D). (E) Cells were transfected with pNF-κB-Luc plasmid (5× NF-κB) for 6 h and then incubated with complete media containing 0–30 μM MH with TNF-α (10 ng·mL−1) for 8 h. Luciferase activity was assessed as described in Methods. Columns, mean of triplicate; bars, SD. #P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the untreated group. *P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the TNF-α-treated group.

MH altered the expression of regulatory proteins involved in cell growth, cell cycle and apoptotic cell death

From the apoptotic cell death and cell cycle pattern, MH decreased the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins of bcl-2 and the inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1/2 (cIAP1/2) as well as GSK-3β and survivin, but increased the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins of bax, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-9 (Figure 3B). Moreover, MH significantly decreased the expression of COX-2 and iNOS, which are involved in the tumour promotion of prostate cancer (Figure 3B). MH also caused a rapid and marked decrease in the protein levels of CDK2, CDK4, cyclin D1 and cyclin E (Figure 3C). As p21 and p27 regulated the transition of G0/G1 by binding to CDK/cyclin complexes, which phosphorylate Rb, leading to cell-cycle progression (Hsu et al., 2007), we determined the effect of MH on p21 and p27 protein levels and on the phosphorylation of Rb by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 3C, MH markedly increased the protein expression of p21, slightly increased that of p27, but suppressed Rb phosphorylation (Figure 3C).

MH inhibited NF-κB activity and cancer cell growth

Highly activated NF-κB is associated with cell survival as well as with the resistance against therapeutics of prostate cancer cells. Activation of PPARγ and inhibition of cancer cell growth could be coupled with inhibition of NF-κB. Thus, we determined the ability of MH to inhibit the DNA binding activity of NF-κB. In untreated human prostate cancer cells (PC3 and LNCaP), we found a high level of constitutive activation of the DNA binding activity of NF-κB and MH (0–30 μM) for 1 h inhibited this DNA binding activity of NF-κB in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3D). In addition, MH (0–30 μM) inhibited TNF–α-induced NF-κB luciferase activity concentration-dependently (Figure 3E), and confocal microscope analysis further demonstrated that the translocation of the NF-κB subunits, p50 and p65, into the nucleus was also decreased by MH (Figure 3F). When we compared cell growth inhibition and the PPARγ and NF-κB DNA binding activities of honokiol, magnolol, obovatol and MH, the extent of cell growth inhibition was associated with the activation of PPARγ (transcriptional and DNA binding activities); significant inhibition of NF-κB was also observed in the cells treated with magnolol and obovatol (Figure 1B and D).

Knock-down of p21 abolished the inhibitory effects of MH on cancer cell growth and NF-κB, and its activation of PPARγ

p21 is a cell cycle inhibitory protein regulating cell cycle progression and is known to be a critical target of the Magnolia family of compounds. Thus, to further investigate the role of p21 in the MH-induced cell cycle arrest, we examined the effect of siRNA p21 and a mutation of p21 on MH-induced cell growth inhibition. Knock-down of p21 with p21 siRNA abolished of the inhibitory effect of MH on cancer cell growth (Figure 4A) and its induction of apoptotic cell death (Figure 4B). Moreover, in p21 siRNA-transfected cells MH-induced inhibition of the G0/G1 cell cycle-regulatory protein expression of CDK and CD4, translocation of p65 and p60, and expression of PPARγ were all abolished (Figure 4C). Similarly, in cells transfected with mutant p21 (mutation of cyclin D1 and CDK4 complex binding site of p21) the inhibitory effects of MH on cell growth (Figure 4D), its induction of apoptotic cell death (Figure 4E), as well as cell cycle-regulatory protein expression and p50 and p65 translocation, and increased expression of PPARγ were all abolished (Figure 4F). These results indicate that the PPARγ and NF-κB signal-mediated inhibitory effects of MH on the growth of PC3 cells are associated with activation of the p21 signal pathway.

Figure 4.

Transfection of PC3 cells with p21 siRNA or p21 mutant plasmid abolished the effect of MH on cell viability, apoptosis and related protein expression. (A–C) The cells were transfected with p21 siRNA for 6 h, grown for 24 h in complete media, and treated with 20 μM MH for 24 h. (D–F) The cells were treated with p21 mutant plasmid which has mutated cyclin D1/cdk4 complex binding site (Cy1 site, 17–24) for 6 h, grown for 24 h in complete media, and treated with 20 μM MH for 24 h. Cell counting (A,D), DAPI and TUNEL staining (B, E), and Western blotting (C, F) were performed as described in Methods. Columns, mean of triplicate; bars, SD. *P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the untreated group.

MH inhibited the growth of SW620 and PC3 tumours in an in vivo xenograft model

In PC3 xenograft studies, MH was administered i.p. daily for 4 weeks to mice with tumours ranging from 100 to 300 mm3 in volume. On day 28, the final tumour weight was recorded. Tumour volumes in mice treated with MH at 40 and 80 mg·kg−1, and cisplatin at 10 mg·kg−1 were 71.0, 57.7 and 46.6% of the control group in PC3 tumour xenografts, respectively. Tumour weight in mice treated with MH at 40 and 80 mg·kg−1 and cisplatin at 10 mg·kg−1 were 40.1, 30.9 and 22.1% of the control group in PC3 tumour xenografts, respectively (Figure 5A). Immunohistochemical analysis of tumour sections by H&E, and proliferation antigens against PCNA and Ki67 staining revealed that both 40 and 80 mg·kg−1 dose-dependently inhibited the growth of the tumour cells (Figure 5B). In addition, there was a trend towards decreased intensity of nuclear staining of p65 and p50 in MH-treated tumour tissue (Figure 5B). Moreover, PPARγ immunoreactivity against anti-PPARγ was also more intense in the tumours treated with MH than in untreated tumour tissues. Similar to its inhibitory effect in vitro, MH enhanced the DNA binding activity of PPARγ, but inhibited NF-κB activity in tumour tissue (Figure 5C). MH increased the expression of bax and cleaved caspases-3, but decreased the expression of bcl-2 in tumour tissue (Figure 5D). Immunohistochemical analysis also showed that the expression of cleaved caspases-3 positive cells was considerably increased in the MH-treated tumour tissue compared with those of the control group. Apoptotic cell death was also significantly increased in the MH-treated tumour tissue (Figure 5B). Moreover, MH significantly increased the expression of p21 and PPARγ in the tumour tissues (Figure 5B–D).

Figure 5.

Effect of 4-O-methylhonokiol (MH) on the tumour growth in PC3 xenografts, in vivo model. Mice with SW620 or PC3 xenografts were treated with MH (40 or 80 mg·kg−1 everyday) or cisplatin (10 mg·kg−1 once a week) for 4 weeks. (A) Tumour volume and weight were measured as described in Methods. Data respresent mean of ten animals; bars show SD. *P < 0.05. (B) Immunohistochemistry; (C) electrophoretic mobility shift assay; and D, Western blotting were performed as described in Methods. Columns, mean of three animals; bars, SD. *P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the untreated group.

Discussion and conclusions

The present data show that MH inhibited the growth of prostate cancer cells through G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptotic cell death. These effects were associated with increased expression of PPARγ and p21, and activation of PPARγ but inhibition of NF-κB activity. Knock-down of p21 with siRNA and mutation of p21 prevented this MH-induced increase in PPARγ expression and activation, NF-κB inactivation, apoptotic cell death as well as the expression of CDK4/cyclin D1. These results suggest that MH inhibits the growth of prostate cancer cells by increasing the expression of p21 as a result of activation of PPAR-γ, but inactivation of NF-κB.

In the present study, MH activated PPARγ and its nuclear translocation, but decreased NF-κB activity and nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 in prostate cancer cells. MH also effectively and significantly induced apoptotic cell death in prostate cancer cells. These effects support the notion that activation of PPARγ, but inactivation of NF-κB, inhibit the growth of cancer cells by promoting apoptotic cell death (Garg and Aggarwal, 2002). Activation of PPARγ and inactivation of NF-κB are implicated in the regulation of growth arrest and/or apoptotic cell death by regulating expression of target genes such as bax, caspase-3, caspase-9, bcl-2, IAP, survivin and GSK-3β (Garg and Aggarwal, 2002). Our data clearly showed that MH inhibited the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation (cyclin D1 and COX-2) and of anti-apoptotic proteins (cIAP1/2 and bcl-2), which are regulated by PPARγ and NF–κB, but increased the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins (cleaved caspase-3 and 9, and bax) in vitro as well as in vivo. This study showed, for the first time, that MH increases PPARγ activity and thus inhibited the growth of prostate cancer cells. These results corroborate previous findings where it was shown that PPARγ agonists, such as troglitazone, curcumin and anti-tumoural pigment epithelium-derived factor, inhibit colon biliary and prostate cancer cell growth through activation of PPARγ, but inactivation of NF-κB (Yamakawa-Karakida et al., 2002; Hirsch et al., 2011; Prakobwong et al., 2011). These effects of MH are similar to those obtained with honokiol and magnolol isolated from M. officinalis; these compound were found to have anti-tumour activity, both in vitro and in vivo, on a variety of cancer cells including prostate cancer cells through inactivation of NF-κB, and inhibition NF-κB target gene expression (Wang et al., 2004; Hahm et al., 2008). In addition, we previously found that MH inhibited colon cancer cells through the inactivation of NF-κB (Oh et al., 2012). These data suggest that the ability of MH to enhance PPARγ activation and its inhibitory action on the constitutive activation of NF-κB are involved in its inhibitory effect on the growth of prostate cancer cells.

The p21 protein regulates G1/S transition by inhibiting CDKs (Chen et al., 1996). MH increased the induction of p21 protein and this was accompanied by a reduced expression of the G0/G1 cell cycle-regulatory proteins, cyclin D1 and CDK4. However, this reduction in expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4 was abolished in the cells after knock-down of p21 with siRNA. Likewise, cells transfected with p21, which had a cyclin/CDK binding site mutation, did not respond to MH. That is, the MH-induced cell growth inhibition, inhibition of the expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4, and phosphorylation of pRb were not observed in p21 mutant cells. These results suggest that the induction of p21 expression may be important in the MH-induced arrest of human prostate cancer cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle. Similar to our findings, honokiol and magnolol induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest via induction of p21 in several cancer cells including prostate cancer cells (Hahm and Singh, 2007; Hsu et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Vaid et al., 2010). We previously found that MH induced cell cycle arrest by induction of p21 in colon cancer cells (Oh et al., 2012). PPARγ and NF-κB are also important for the p21-mediated cell cycle arrest of cancer cell growth (Hellin et al., 2000). Increased NF–κB-dependent p21 expression was observed in human cancer cells resistant to chemotherapeutics (Chang and Miyamoto, 2006). In the present study, the effects of MH on PPARγ, and reciprocal converse effects of NF-κB with p21 and p27 expression were found to correlate with its ability to inhibit cell growth inhibition and induce apoptotic cell death. The MH-induced PPARγ activation and NF-κB inactivation were abolished in the cells after knock-down of p21 with siRNA as well as in the cells transfected with mutant p21. We also found that MH, concomitant with the increased expression of p21 and p27, also enhanced the phosphorylation of Rb, the downstream target gene of p21. MH also increased the expression of p21 and p27 with decreased expression of the G0/G1 phase of cell cycle regulatory proteins of cycline D1 and E, and CDK2 and CDK4 in prostate cancer xenograft nude mice tumour tissue. Similar to our results, a recent study demonstrated that an aqueous extract of M. officinalis increased p21 expression and decreased NF-κB in human urinary bladder cancer cells (Lee et al., 2007). Moreover, recent studies have shown that anti-cancer drugs are able to inhibit the growth of several human cancer cells through up-regulation of p21 accompanied by activation of PPARγ, but inhibition of NF-κB activation. For example, pioglitazone, a PPARγ agonist inhibited p21-mediated prostate cancer cell growth (Hirsch et al., 2011). PPARγ stimulates sulindac sulfide-mediated p21 expression in prostate epithelial cells (Jarvis et al., 2005). Soy peptide increased p21 in human breast MCF-7 tumour cells via inactivation of NF-κB, and thus inhibited their growth (Park et al., 2009). Curcumin inhibited human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell growth via NF-κB inactivation-induced up-regulation of p21 (Chiu and Su, 2009). Lycopene inhibited the growth of prostate cancer cells by inactivation of NF-κB and up-regulation of p21 (Palozza et al., 2010). We also found that MH inhibited colon cancer cell growth by p21-mediated NF-κB inactivation (Oh et al., 2012). These data and ours suggest that both the enhancing ability of MH on PPARγ and its inhibitory effect on the constitutive activation of NF-κB are related to the increased expression of p21, and the modification of these cooperative signals is involved in its inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth. However, it is not clear how changes in the expression of p21 alter PPARγ and NF-κB, or whether p21 is downstream of PPARγ and/or NF-κB or vice versa. It is noteworthy that there are PPRE as well as a NF–κB-binding element on the p21 promoter (Han et al., 2004; Sue et al., 2009). Thus, increased activity of PPAR-γ or reduced activity of NF-κB induced by MH could enhance or inhibit the expression of p21. It is also interesting to note that the PPARγ agonist thiazolidinedione inhibits cancel growth via inhibition of nucleophosmin (NPM) expression, which is known to induce p53 phosphorylation and p21 expression (Galli et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that the activating effect of MH on PPARγ may affect the expression of proteins like NPM, which increase p21 expression. These data suggest that p21 acts downstream of PPARγ and NF-κB.

Pharmacokinetic data have shown that MH has good oral and intestinal absorption as determined by the Caco-2a with easy distribution into tissues (unpublished data). The dosage of MH used in the present in vivo study are within the range employed in other previous studies showing anti-tumour effects of the compounds isolated from M. officinalis; i.p. administration of honokiol at 80 mg·kg−1 for 31 days displayed significant anti-cancer activity (Chen et al., 2004). Treatment with liposomal honokiol at 25 mg·kg−1 reduced the tumour sizes by 42% compared with the untreated tumour in Lewis lung carcinoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice (Hu et al., 2008). In toxicology studies, we demonstrated that M. officinalis extract did not produce any toxic effects in the 21 and 90 day toxicity studies, and that up to 240 mg·kg−1 is a no-observed-adverse-effects-level (Liu et al., 2007), which is similar to the range of doses used in the present study if it is assumed the extract has about 15% of 4-O-methyhonokiol, as described elsewhere (Oh et al., 2009). We have also evaluated the long-term toxicity including carcinogenicity of MH using a prediction program (preADME version 1.0.2, BMDRC, Seoul, Korea), and found that it was predicted not to be toxic or carcinogenic to rodents (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that MH should be considered for further clinical investigation to determine its possible chemopreventive and/or therapeutic efficacy against human prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (MRC, 2011-0029480).

Glossary

- CDK

cycline-dependent kinase

- CNBr

cyanogen bromide

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- GSK-3 β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 β

- IAP1

inhibitor of apoptosis 1

- iNOS

inducible NOS

- MH

4-O-methylhonokiol

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Chemical structure of MH, cell viability in normal prostate cells, and luciferase activity, DNA binding activity of PPARγ and NF-κB by other components isolated from Magnolia officinalis. (A) Chemical structure of MH. (B) PWR-1E normal prostate cells were treated with various doses (0–30 μM) MH for 72 h. Morphological changes were observed under a microscope. Cell viability was determined by direct cell counting using trypan blue as described in Methods. (C,D) Transcriptional and DNA binding activities were determined by luciferase activity and EMSA. Luciferase activity was determined in the cells transfected with PPAR-γ plasmid construct after treatment of MH and other several agents MH for 24 h as described in Methods. Columns, mean of triplicate; bars, SD. Prostate cancer cells treated with MH and other agents were incubated for 1 h. Nuclear extract from cells treated with MH, honokiol, magnolol and obovotaol for 1 h was incubated in binding reactions of 32P-end-labelled oligonucleotide containing the PPRE or κB sequence (D). EMSA was performed as described in Methods. D, After Cells were treated with 0–20 μM of MH, honokiol (H), magnolol (M) and obovatol (O) for 24 h, cell viability was determined by direct cell counting using trypan blue. Points and Columns, mean of triplicate; bars, SD. *, P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences from the untreated group.

References

- Allen CT, Ricker JL, Chen Z, Van Waes C. Role of activated nuclear factor-kappaB in the pathogenesis and therapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2007;29:959–971. doi: 10.1002/hed.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban JO, Lee HS, Jeong HS, Song S, Hwang BY, Moon DC, et al. Thiacremonone augments chemotherapeutic agent-induced growth inhibition in human colon cancer cells through inactivation of nuclear factor-{kappa}B. Mol Cancer Res. 2009a;7:870–879. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban JO, Oh JH, Hwang BY, Moon DC, Jeong HS, Lee S, et al. Inflexinol inhibits colon cancer cell growth through inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activity via direct interaction with p50. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009b;8:1613–1624. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs JR, Kraft AS. Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase and cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 1995;73:509–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00198902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PY, Miyamoto S. Nuclear factor-kappaB dimer exchange promotes a p21(waf1/cip1) superinduction response in human T leukemic cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:101–112. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Wang T, Wu YF, Gu Y, Xu XL, Zheng S, et al. Honokiol: a potent chemotherapy candidate for human colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3459–3463. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i23.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Saha P, Kornbluth S, Dynlacht BD, Dutta A. Cyclin-binding motifs are essential for the function of p21CIP1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4673–4682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LC, Liu YC, Liang YC, Ho YS, Lee WS. Magnolol inhibits human glioblastoma cell proliferation through upregulation of p21/Cip1. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:7331–7337. doi: 10.1021/jf901477g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F, Shen J, Xu X, Luo X, Chen K, Shen X, et al. Interaction models of a series of oxadiazole-substituted alpha-isopropoxy phenylpropanoic acids against PPARalpha and PPARgamma: molecular modeling and comparative molecular similarity indices analysis studies. Protein Pept Lett. 2009;16:150–162. doi: 10.2174/092986609787316207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu TL, Su CC. Curcumin inhibits proliferation and migration by increasing the Bax to Bcl-2 ratio and decreasing NF-kappaBp65 expression in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:469–475. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcet X, Llobet D, Pallares J, Matias-Guiu X. NF-kB in development and progression of human cancer. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-1264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LE, Arbiser JL. Honokiol, a multifunctional antiangiogenic and antitumor agent. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1139–1148. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli A, Ceni E, Mello T, Polvani S, Tarocchi M, Buccoliero F, et al. Thiazolidinediones inhibit hepatocarcinogenesis in hepatitis B virus-transgenic mice by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-independent regulation of nucleophosmin. Hepatology. 2010;52:493–505. doi: 10.1002/hep.23669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear transcription factor-kappaB as a target for cancer drug development. Leukemia. 2002;16:1053–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AK, Steele R, Ray RB. Knockdown of MBP-1 in human prostate cancer cells delays cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23652–23657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm ER, Singh SV. Honokiol causes G0-G1 phase cell cycle arrest in human prostate cancer cells in association with suppression of retinoblastoma protein level/phosphorylation and inhibition of E2F1 transcriptional activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2686–2695. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm ER, Arlotti JA, Marynowski SW, Singh SV. Honokiol, a constituent of oriental medicinal herb Magnolia officinalis, inhibits growth of PC-3 xenografts in vivo in association with apoptosis induction. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1248–1257. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Sidell N, Fisher PB, Roman J. Up-regulation of p21 gene expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in human lung carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1911–1919. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon RC, Zhou L, Feng T, Breyer B, Cheng H, Jiang W, et al. Nuclear receptor agonists as potential differentiation therapy agents for human osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1288–1294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellin AC, Bentires-Alj M, Verlaet M, Benoit V, Gielen J, Bours V, et al. Roles of nuclear factor-kappaB, p53, and p21/WAF1 in daunomycin-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:870–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J, Johnson CL, Nelius T, Kennedy R, Riese W, Filleur S. PEDF inhibits IL8 production in prostate cancer cells through PEDF receptor/phospholipase A2 and regulation of NFkappaB and PPARgamma. Cytokine. 2011;55:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Kawinski E, Karr JP, Rosenthal H, Chu TM, et al. Mirand EA,Murphy GP. LNCaP model of human prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1809–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YF, Lee TS, Lin SY, Hsu SP, Juan SH, Hsu YH, et al. Involvement of Ras/Raf-1/ERK actions in the magnolol-induced upregulation of p21 and cell-cycle arrest in colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:275–283. doi: 10.1002/mc.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Chen LJ, Liu L, Chen X, Chen PL, Yang G, et al. Liposomal honokiol, a potent anti-angiogenesis agent, in combination with radiotherapy produces a synergistic antitumor efficacy without increasing toxicity. Exp Mol Med. 2008;40:617–628. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovska I, Ball AS, Diaz RL, Magnus JF, Kibukawa M, Schelter JM, et al. MicroRNAs in the miR-106b family regulate p21/CDKN1A and promote cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2167–2174. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01977-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MC, Gray TJ, Palmer CN. Both PPARgamma and PPARdelta influence sulindac sulfide-mediated p21WAF1/CIP1 upregulation in a human prostate epithelial cell line. Oncogene. 2005;24:8211–8215. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Park KS, Chung SY, Sheen YY, Moon DC, Song YS, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activator 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits neuroblastoma cell growth through induction of apoptosis: association with extracellular signal-regulated kinase signal pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:505–517. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Szczepanski MJ, Lee YJ. Magnolol induces apoptosis via inhibiting the EGFR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in human prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:1113–1122. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Koo TH, Hwang BY, Lee JJ. Kaurane diterpene, kamebakaurin, inhibits NF-kappa B by directly targeting the DNA-binding activity of p50 and blocks the expression of antiapoptotic NF-kappa B target genes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18411–18420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Kim HM, Cho YH, Park K, Kim EJ, Jung KH, et al. Aqueous extract of Magnolia officinalis mediates proliferative capacity, p21WAF1 expression and TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB activity in human urinary bladder cancer 5637 cells; involvement of p38 MAP kinase. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:729–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Yuk DY, Song HS, Yoon Y, Jung JK, Moon DC, et al. Growth inhibitory effects of obovatol through induction of apoptotic cell death in prostate and colon cancer by blocking of NF-kappaB. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;582:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Lee YM, Lee CK, Jung JK, Han SB, Hong JT. Therapeutic applications of compounds in the Magnolia family. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:157–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MF, Meng TC, Rao PS, Chang C, Schonthal AH, Lin FF. Expression of human prostatic acid phosphatase correlates with androgen-stimulated cell proliferation in prostate cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5939–5947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SY, Liu JD, Chang HC, Yeh SD, Lin CH, Lee WS. Magnolol suppresses proliferation of cultured human colon and liver cancer cells by inhibiting DNA synthesis and activating apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2002;84:532–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind DS, Hochwald SN, Malaty J, Rekkas S, Hebig P, Mishra G, et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B is upregulated in colorectal cancer. Surgery. 2001;130:363–369. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Zhang X, Cui W, Li N, Chen J, Wong AW, et al. Evaluation of short-term and subchronic toxicity of magnolia bark extract in rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;49:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JH, Kang LL, Ban JO, Kim YH, Kim KH, Han SB, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of 4-O-methylhonokiol, compound isolated from Magnolia officinalis through inhibition of NF-kappaB [corrected] Chem Biol Interact. 2009;180:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JH, Ban JO, Cho MC, Jo M, Jung JK, Ahn B, et al. 4-O-methylhonokiol inhibits colon tumor growth via p21-mediated suppression of NF-kappaB activity. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palozza P, Colangelo M, Simone R, Catalano A, Boninsegna A, Lanza P, et al. Lycopene induces cell growth inhibition by altering mevalonate pathway and Ras signaling in cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1813–1821. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papineni S, Chintharlapalli S, Safe S. Methyl 2-cyano-3,11-dioxo-18 beta-olean-1,12-dien-30-oate is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist that induces receptor-independent apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:553–565. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K, Choi K, Kim H, Kim K, Lee MH, Lee JH, et al. Isoflavone-deprived soy peptide suppresses mammary tumorigenesis by inducing apoptosis. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41:371–381. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.6.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, Kasem S, et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakobwong S, Gupta SC, Kim JH, Sung B, Pinlaor P, Hiraku Y, et al. Curcumin suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in human biliary cancer cells through modulation of multiple cell signaling pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1372–1380. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan SK, Gartel AL. The PPAR-gamma agonist pioglitazone post-transcriptionally induces p21 in PC3 prostate cancer but not in other cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:582–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond A. Nf-kappa B, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:664–674. doi: 10.1038/nri887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JH, Choi HS, Pugliese A, Lee SY, Chae JI, Choi BY, et al. (–)-Epigallocatechin gallate regulates CD3-mediated T cell receptor signaling in leukemia through the inhibition of ZAP-70 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28370–28379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802200200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son DJ, Park MH, Chae SJ, Moon SO, Lee JW, Song HS, et al. Inhibitory effect of snake venom toxin from Vipera lebetina turanica on hormone-refractory human prostate cancer cell growth: induction of apoptosis through inactivation of nuclear factor kappaB. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:675–683. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue YM, Chung CP, Lin H, Chou Y, Jen CY, Li HF, et al. PPARdelta-mediated p21/p27 induction via increased CREB-binding protein nuclear translocation in beraprost-induced antiproliferation of murine aortic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C321–C329. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00069.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh J, Rabson AB. NF-kappaB activation in human prostate cancer: important mediator or epiphenomenon? J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:100–117. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid M, Sharma SD, Katiyar SK. Honokiol, a phytochemical from the Magnolia plant, inhibits photocarcinogenesis by targeting UVB-induced inflammatory mediators and cell cycle regulators: development of topical formulation. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:2004–2011. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waku T, Shiraki T, Oyama T, Morikawa K. Atomic structure of mutant PPARgamma LBD complexed with 15d-PGJ2: novel modulation mechanism of PPARgamma/RXRalpha function by covalently bound ligands. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Chen F, Chen Z, Wu YF, Xu XL, Zheng S, et al. Honokiol induces apoptosis through p53-independent pathway in human colorectal cell line RKO. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2205–2208. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i15.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf I, O'Kelly J, Wakimoto N, Nguyen A, Amblard F, Karlan BY, et al. Honokiol, a natural biphenyl, inhibits in vitro and in vivo growth of breast cancer through induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:1529–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa-Karakida N, Sugita K, Inukai T, Goi K, Nakamura M, Uno K, et al. Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma induces apoptosis of leukemia cells by down-regulating the c-myc gene expression via blockade of the Tcf-4 activity. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:513–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SE, Hsieh MT, Tsai TH, Hsu SL. Down-modulation of Bcl-XL, release of cytochrome c and sequential activation of caspases during honokiol-induced apoptosis in human squamous lung cancer CH27 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:1641–1651. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CH, Kan SF, Pu HF, Jea Chien E, Wang PS. Apoptotic signaling in bufalin and cinobufagin-treated androgen-dependent and -independent human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2467–2476. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.