Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the acute effects of initiating a diuretic drug on risk of fracture. We evaluated the relationship between initiating a diuretic drug and the occurrence of hip fracture.

Methods

The study sample included 2, 118, 793 persons aged ≥ 50 years enrolled in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) between 1986–2010. The effect of a new start of a diuretic drug or comparator medication (ACE-Inhibitor) on risk of hip fracture was assessed using a case-crossover and case-control study during the 1–7, 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 days following drug initiation.

Results

Included were 28, 703 individuals with an incident hip fracture over a mean of 7.9 years follow-up. In the case-crossover study, the risk of experiencing a hip fracture was increased during the first 7 days following loop diuretic drug initiation (OR=1.8; 95% CI: 1.2, 2.7). The elevated risk did not continue during the 8–14, 15–21, or 22–28 days following drug initiation. For thiazide diuretics, the risk of hip fracture was elevated 8-14 days after drug initiation (OR=2.2; 95% CI: 1.2, 3.9). No such association was observed in the 1–7, 15–21, or 22–28 days following thiazide drug initiation. ACE-inhibitor initiation was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of hip fracture. Similar results were observed using a case-control study.

Conclusions

The risk of hip fracture was transiently elevated around two-fold shortly after the new start of a loop or thiazide diuretic drug. Awareness of these short term risks may reduce hip fractures and other injurious falls in vulnerable adults.

Keywords: loop diuretic, thiazide diuretic, hip fracture, acute risk

Introduction

Diuretics may affect hip fracture risk through their effects on bone mineral density as well as risk of falls. Thiazide diuretics, which promote renal calcium absorption, have been associated with an increase in bone mineral density at the spine and hip [1, 2], whereas loop diuretics, which promote renal calcium excretion, have been associated with a decrease in bone mineral density at the hip and ultradistal forearm [3, 4]. Use of any diuretic has been associated with a modest increase in the risk of falls (OR=1.07; 95% CI: 1.01-1.14) [5].

Conflicting data exists with regards to diuretic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. For example, most studies suggest that thiazide diuretic use is associated with a decreased risk of hip fracture [6, 7, 8, 9], whereas a few studies suggest that thiazide diuretic use is associated with an increased fracture risk [10, 11]. Loop diuretic use has been associated with an increased risk of hip fracture in some [10, 12], but not all [3, 13] studies. These conflicting results may be explained in part, by differential effects of diuretics on fracture risk based on duration of use. We hypothesized that new users of a diuretic would be at a particularly high risk of hip fracture immediately following initiation of the diuretic drug. We speculated that this would be due to acute urinary symptoms associated with drug initiation that could result in an injurious fall while hurrying to the toilet.

In order to examine the potential association between initiation of a diuretic drug and the acute risk of hip fracture, we performed a nested case-crossover and case-control study among more than 2 million individuals aged ≥ 50 years of The Health Improvement Network (THIN). To test our hypothesis that urinary symptoms are responsible for the increased risk of fracture, we also examined the effects of initiating a comparator medication (ACE-inhibitor) that would not be expected to produce urinary symptoms.

Methods

Subjects

THIN is a voluntary, primary care database comprised of some clinical and all administrative data from more than 400 practices and 7 million persons in the United Kingdom. During the study period (1986–2010), 2, 118, 793 persons aged ≥ 50 years were enrolled in THIN. Participants of our study included 28, 703 members with a hip fracture between years 1987–2010.

Case-Crossover Study

The case-crossover design was specifically developed to assess the effects of a transient exposure on an acute event [14]. In a case-crossover analysis, exposure during a relevant period of time preceding the event (hazard period) is compared with exposure status during periods of time without an event (control period) in the same individual. Self-matching eliminates confounding by risk factors that are constant within an individual over the sampling period.

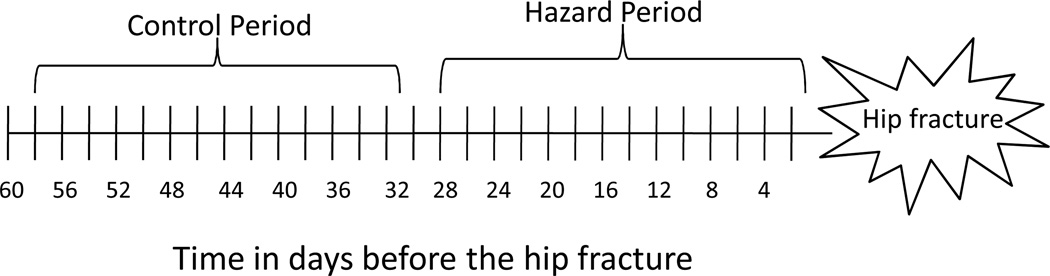

Specifically, for each incident hip fracture, we compared the prescription of a new diuretic drug during the 1–7 days before the hip fracture (hazard period) with the prescription during the 31–38 days before the hip fracture (control period; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the case-crossover study design used to determine the effect of diuretic drug initiation on the acute risk of hip fracture.

Because it is unknown when a new diuretic drug might have its maximal influence on the risk of hip fracture, we considered alternative hazard periods: 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 days before the hip fracture, respectively. Corresponding control periods were selected 30 days before each hazard block. This method of varying the hazard period has been recommended in situations where the biological effects of the exposure are unknown [14].

Case-Control Study

For each case of an incident hip fracture, a matched control was selected from the source population. Controls were matched to cases by age, sex, and date of entry into THIN in a 1:1 ratio. Exposure to a new diuretic drug among cases was assessed within the 7 days immediately prior to the occurrence of the hip fracture. For controls, exposure was assessed within the 7 days before the index date (i.e., date when the matched case experienced a hip fracture). Similar to the case-crossover study, we considered alternative exposure periods of interest: 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 days before the hip fracture or index date.

Hip Fracture Ascertainment

We defined incident hip fracture as any fracture of the proximal femur that occurred ≥ 365 days from the time of enrollment or study entry as classified by diagnostic and procedural Read codes (Appendix 1). Read codes have previously been validated to identify 96% of hip fractures as compared with medical record confirmation [15].

Diuretic Drug Ascertainment

Using prescription codes, a new diuretic prescription was defined as an enteral diuretic prescription without a history of use within the past 180 days. Diuretics were categorized into two categories: loop diuretic (e.g., bumetanide, ethacrynic acid, furosemide, torsemide) and thiazide and thiazide-related diuretic (e.g., bendroflumethiazide, chlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, clopamide, cyclopenthiazide, hydroflumethiazide, hydrochlorothiazide, indapamide, methyclothiazide, metolazone, polythiazide, quinethazone, and xipamide).

Comparator Medication

We selected a comparator class of medications that is used to manage similar clinical conditions as diuretics but is not associated with urinary urgency: angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I). A new ACE-I prescription was defined as an enteral ACE-I prescription without a history of use within the past 180 days.

Covariate Assessment

We collected information on additional characteristics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, prior history of fracture, and use of osteoporosis medications. BMI was categorized as normal (<25kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2). Smoking status was categorized as never smoker, former smoker, and current smoker. Prior history of fracture (yes versus no) was ascertained using diagnostic and historical Read codes. A fracture at any site except the face, hands, or toes was considered. Osteoporosis medications included any use of oral estrogen, raloxifene, calcitonin, oral and IV bisphosphonates, or teriparatide.

Statistical analysis

We used conditional logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for a hip fracture in the days following a new prescription for a loop diuretic or thiazide diuretic separately, compared with periods without a new drug prescription. In the case-crossover analysis, participants were compared with themselves 30 days earlier, minimizing the need to adjust for time invariant covariates. Models in the case-crossover analysis included an indicator term to adjust for a concomitant new prescription for an ACE-I. For the case-control study, models were adjusted for BMI, smoking status, prior history of fracture, and use of osteoporosis medications.

In order to explore the hypothesis that urinary symptoms, rather than changes in blood pressure, were responsible for the acute increased risk of hip fracture, we performed an additional case-crossover analysis using a comparator class of medications (ACE-I).

In an effort to understand the absolute effect of a new diuretic prescription on the acute risk of hip fracture, we estimated the absolute risk of hip fracture after initiation of a diuretic drug. Absolute risk was calculated using the following formula: (IRR*OR) – IRR, where IRR represents the baseline rate of incident hip fracture, and OR represents the odds ratio as calculated by the case-crossover study. We used SAS version 9.2 for all analyses.

Results

Of the 2, 118, 793 eligible THIN members, 28, 703 experienced an incident hip fracture during a mean follow-up time of 7.9 ± 5.0 years. Participants with an incident hip fracture were less likely to be obese compared with those without a hip fracture (6.5 vs 11.3%; Table 1). Participants with an incident hip fracture were more likely to have a history of fracture (18.8 vs 8.6%) and use osteoporosis medications (12.5 vs 10.0%) compared with those without a hip fracture.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cases and controls in the THIN cohort as categorized by whether they experienced a hip fracture (mean ± standard deviation or %, as indicated)

| Hip fracture (n=28,213) |

No hip fracture (n=28,213) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74 ± 11 | 74 ± 11 |

| Female (%) | 77.2 | 77.2 |

| Body mass index categorization (%) |

||

| Normal | 35.9 | 27.2 |

| Overweight | 16.9 | 21.8 |

| Obese | 6.5 | 11.3 |

| Missing | 40.7 | 39.7 |

| Smoking status (%) | ||

| Never smoker | 43.9 | 47.1 |

| Former smoker | 17.1 | 17.4 |

| Current smoker | 12.2 | 7.5 |

| Missing | 26.8 | 28 |

| Prior fracture (%) | 18.8 | 8.6 |

| Osteoporosis medication (%) | 12.5 | 10 |

Case-crossover analysis

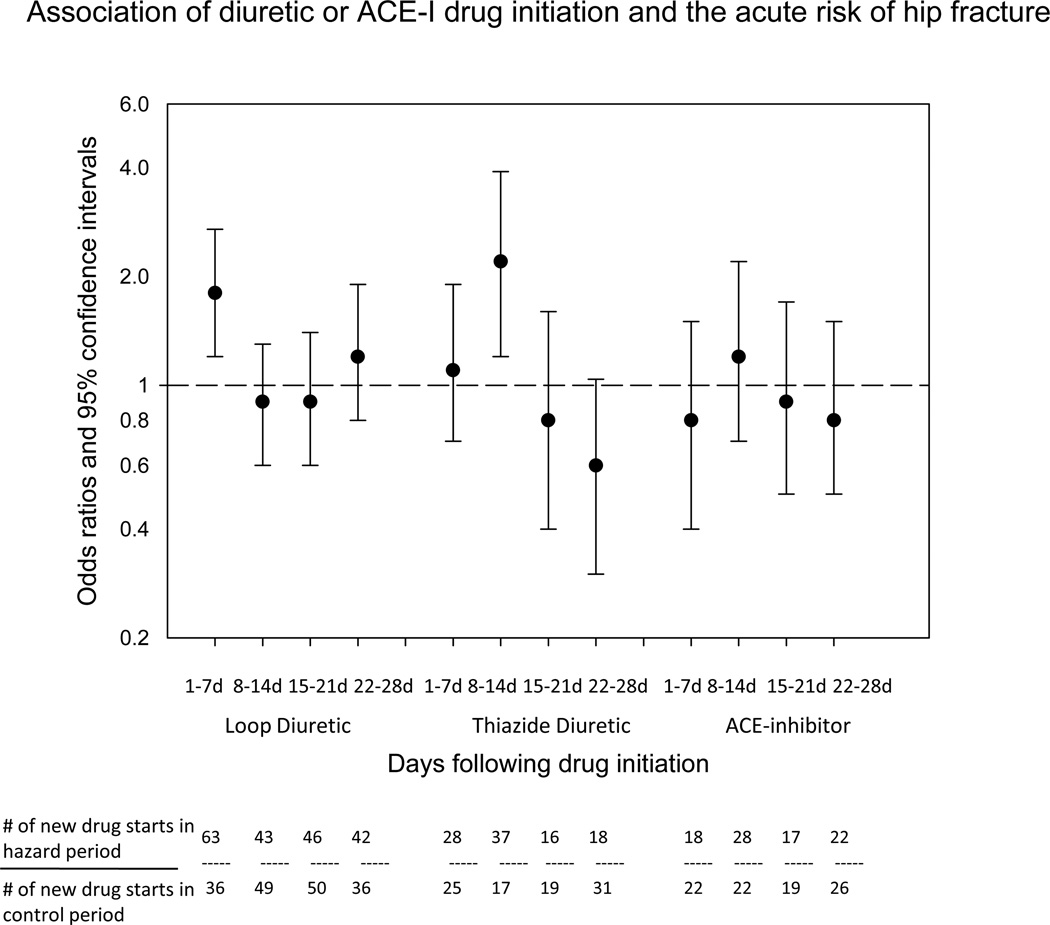

Among participants, 63 hip fractures occurred within the 7 days following loop diuretic initiation (Figure 2). The majority of the new loop diuretic prescriptions during the hazard period were for furosemide. The odds of hip fracture were elevated in the 7 days following loop diuretic drug initiation compared with periods of time with no diuretic drug starts (OR=1.8; 95% CI: 1.2, 2.7). There was no increased risk of hip fracture observed during days 8–14, 15–21, or 21–28 following loop diuretic drug initiation (OR=0.9, 0.9, and 1.2, respectively).

Figure 2.

Association between diuretic or ACE-I initiation and the acute risk of hip fracture in a case-crossover study of 28,703 persons from The Health Improvement Network with hip fracture.

Only 28 participants experienced a hip fracture within 7 days of initiating a thiazide diuretic drug. There was no increased risk of fracture observed in the first 7 days following thaizide drug initiation (OR=1.1; 95% CI: 0.7, 1.9). The maximum effect of a thiazide diuretic on the acute risk of hip fracture occurred 8–14 days following drug initiation (OR=2.2, 95% CI: 1.2, 3.9), with no significant risk of hip fracture during days 15–21 or 22–28.

Case-control analysis

Of 28, 213 cases with incident hip fracture included in the case-control analysis, 62 (0.2%) had a new loop diuretic prescription during the 7 days prior to the hip fracture. The corresponding number of controls with a new loop diuretic prescription was 29. The risk of experiencing a hip fracture was increased during the first 7 days following loop diuretic drug initiation (OR=2.1; 95% CI: 1.4, 3.4; Table 2). The elevated risk remained in the 8–14, 15–21 and 22–28 days following loop diuretic drug initiation, with marginal statistical significance (OR: 1.7, 1.5, and 1.9, respectively).

Table 2.

Odds ratios of hip fracture after a new start of a diuretic drug in a case-control study of 28,213 THIN participants with hip fracture

| Diuretic drug type | Time relative to index dateb |

# of new prescriptions among cases |

# of new prescriptions among controls |

Unadjusted odds ratio |

95% confidence intervals |

Adjusteda odds ratio |

95% confidence intervals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loop diuretic | 1–7 days | 62 | 29 | 2.1 | 1.4, 3.3 | 2.1 | 1.4, 3.4 |

| 8–14 days | 43 | 24 | 1.8 | 1.1, 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.0, 2.9 | |

| 15–21 days | 46 | 29 | 1.6 | 1.0, 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.0, 2.5 | |

| 22–28 days | 42 | 26 | 1.6 | 1.0, 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.1, 3.2 | |

| Thiazide diuretic | 1–7 days | 28 | 24 | 1.2 | 0.7, 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.7, 2.3 |

| 8–14 days | 37 | 15 | 2.5 | 1.4, 4.5 | 2.7 | 1.5, 5.0 | |

| 15–21 days | 16 | 25 | 0.6 | 0.3, 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.3, 1.2 | |

| 22–28 days | 18 | 25 | 0.7 | 0.4, 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.4, 1.4 | |

adjusted for BMI, smoking status, fracture history, and osteoporosis medication use

For cases, the index date is the date of hip fracture. For controls, the index date is the date when the matched case experienced a hip fracture.

For thiazide diuretics, 28 cases (0.1%) had a new prescription during the 7 days prior to the hip fracture, compared with 24 new prescriptions in the controls. The risk of experiencing a hip fracture was elevated in the 8–14 days following thiazide drug initiation (OR=2.7; 95% CI: 1.5, 5.0), but not during the other time periods.

Comparator drug class analysis

There was no statistically significant association between initiation of an ACE-I drug and the acute risk of hip fracture in the first 28 days (Figure 2). The maximum risk of hip fracture occurred 8–14 days after ACE-I initiation (OR=1.2; 95% CI: 0.7, 2.2).

Absolute risk estimate

The baseline rate of incident hip fracture in the THIN cohort was 1.9 hip fractures/1,000 person years. We estimate the absolute risk of hip fracture within 7 days of a new loop diuretic prescription is 2.9 per 100,000 new loop diuretic prescriptions. The absolute risk of hip fracture 8–14 days following thiazaide drug initiation is 4.4 per 100,000 new thiazide drug prescriptions.

Conclusions

Our results from a population based study suggest that the relative risk of experiencing a hip fracture is increased nearly two-fold during the 7 days following initiation of a loop diuretic drug. This acute risk of hip fracture appears to be greatest during the first week, but not the second week, following loop diuretic drug initiation. For thiazide diuretics, the risk of experiencing a hip fracture was increased in the 8–14 days following drug initiation. Similar results were obtained using both a case-crossover and case-control approach, although the case-control estimates were larger, likely due to unmeasured confounding.

Although the absolute risk of hip fracture associated with diuretic initiation was small (i.e., roughly 3-4 excess hip fractures per 100,000 new diuretic prescriptions), our findings are important as it is likely that initiation of these drugs increases the risk of other injurious falls as well. Our study identifies a narrow window of time following drug initiation when diuretic users are particularly vulnerable to injurious falls and when interventions to reduce falls might be effective. Providers should inform patients of the transient risk of injury associated with drug initiation in an effort to prevent hip fractures and other injurious falls.

Previous studies of diuretic drugs have primarily focused on the long term risk of fracture as mediated by their effects on bone mineral density and fall risk [16, 17]. In these studies, long term use of diuretics (≥ 1–3 years) [13, 18] and increased doseage [18] are important determinants of fracture risk. In our study, we were interested in the effect of initiating a diuretic drug on the acute risk of hip fracture as mediated exclusively by falls rather than bone mineral density. We found the odds ratio of hip fracture in the 7 days following a new loop diuretic prescription was 1.8 (95% CI 1.2, 2.7). This represents a greater relative risk in comparison with the effect of loop diuretic drug use on falls as estimated by Leipzig (OR, 0.90; 95% CI 0.73–1.12) [19] or any diuretic drug use on falls as estimated by Woolcott (OR, 1.07; 95% CI 1.01–1.14) [5]. Thus, new loop diuretic drug users seem to be particularly vulnerable to falls and injury in the days immediately following the new prescription.

Previous work by our group supports a heightened risk of falls immediately following a new loop diuretic prescription: among nursing home residents, a new prescription or dose increase of a loop diuretic was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of falls in the one day following the prescription drug change [20]. We speculate that this acute effect on falls may be mediated by urinary urgency and frequency that is common with loop diuretic drug initiation, and it could result in a fall while hurrying to the toilet. Tolerance to loop diuretics occurs quickly such that diuresis and naturesis is greatest after the first dose of a loop diuretic, with a reduced response to subsequent doses [21]. Although we cannot exclude acute changes in blood pressure associated with drug initiation as the cause of falls and injury, we found a smaller and non-statistically significant association between new ACE-inhibitor prescriptions, a powerful antihypertensive, and the acute risk of hip fracture. Our findings are consistent with a self-controlled case series study by Gribbin et al, that demonstrated only a mild, and non-statistically significant elevated risk of falls in the 21 days following ACE-I initiation (IRR=1.27; 95% CI, 0.88, 1.84) [22].

For thiazide diuretic drugs, we found an increased relative risk of hip fracture in the second week, but not the first week, following drug initiation. This finding could be due to chance. However, Gribbin et al. also found that new users of thiazide diuretics were at more than a two-fold increased risk of falls during the 21 days following drug initiation [22]. We are not aware of any pharmacologic differences in thiazide diuretics that would explain the delayed effect that we observed. Instead, it is possible that new users of thiazide diuretics are less likely to begin their prescription immediately, resulting in misclassification of the first two hazard blocks. Future studies should confirm the temporal association between thiazide initiation and injurious falls.

Our study has several limitations. First, hip fractures were ascertained through administrative data. Traumatic fractures and fractures related to malignancy may have been included. Of note, the observed rate of incident hip fractures in our study (1.9 hip fractures/1,000 person years) is similar to the estimated rate of hip fracture in women in England and Wales (1.7 hip fractures/1,000 person years) [23]. Thus, it is unlikely that we misclassified a large number of hip fractures. Second, we are unable to verify that participants were adherent with new drug prescriptions. If non-adherence was common, the true effect of diuretic drug initiation on the acute risk of hip fracture may be even greater than we estimated. Third, we were unable to confirm that hip fractures were related to a fall. A cross-sectional study of post-menopausal women suggests that >95% of hip fractures are related to a fall [24]. Thus, exclusion of non-fall related hip fractures would be unlikely to change our results.

Finally, we are unable to completely separate the effects of the new diuretic prescription from the associated medical condition with respect to risk of hip fracture. This limitation is not unique to our study, but rather it applies to all observational pharmacoepidemiologic studies [25]. We recognize that in the case-control study, cases with a hip fracture may have been more likely to have cardiovascular disease as compared with controls, given the known association between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease [26]. We feel this is unlikely to fully explain our results, given the similar effect estimates obtained using a self-matched, case-crossover study. Nonetheless, in the case-crossover study, acute changes in medical status including elevated blood pressure and cardiac decompensation are still possible between the control and hazard periods and may contribute to the risk of hip fracture. We did not have information on the indication for which the drug was prescribed, and therefore, we were unable to adjust for acute changes in medical status. Our finding that a new prescription of an ACE-I, which is also used to manage heart failure and hypertension, was not associated with the acute risk of hip fracture suggests that the fracture risk we observed may be attributable, at least in part, to the diuretic drug itself.

In conclusion, we found that new users of loop and thiazide diuretics are at an elevated risk of hip fracture in the days following drug initiation. We suggest that clinicians inform patients of these transient risks. Frequent toileting may be useful for continent patients in an effort to reduce a fall due to hurrying. Future studies should consider both the acute and long term effects of regularly administered medications on the risk of falls and injury.

Acknowledgements and Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the NIA (K23 AG033204), NIAMS (P60AR047785), Boston University School of Medicine, and the Men’s Associates of Hebrew SeniorLife.

Analyses were presented in part on September 16, 2011 at the American Society for Bone & Mineral Research annual meeting in San Diego, CA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bolland MJ, Ames RW, Horne AM, Orr-Walker BJ, Gamble GD, et al. The effect of treatment with a thiazide diuretic for 4 years on bone density in normal postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:479–486. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0259-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaCroix AZ, Ott SM, Ichikawa L, Scholes D, Barlow WE. Low-dose hydrochlorothiazide and preservation of bone mineral density in older adults. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:516–526. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-7-200010030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim LS, Fink HA, Blackwell T, Taylor BC, Ensrud KE. Loop diuretic use and rates of hip bone loss and risk of falls and fractures in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Heickendorff L, Andreasen F, Mosekilde L. Loop diuretics increase bone turnover and decrease BMD in osteopenic postmenopausal women: results from a randomized controlled study with bumetanide. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:163–170. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1952–1960. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Reduced fracture risk in users of thiazide diuretics. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;76:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felson DT, Sloutskis D, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Kiel DP. Thiazide diuretics and the risk of hip fracture. Results from the Framingham Study. Jama. 1991;265:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlienger RG, Kraenzlin ME, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of beta-blockers and risk of fractures. Jama. 2004;292:1326–1332. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoofs MW, van der Klift M, Hofman A, de Laet CE, Herings RM, et al. Thiazide diuretics and the risk for hip fracture. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:476–482. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidrich FE, Stergachis A, Gross KM. Diuretic drug use and the risk for hip fracture. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:1–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taggart HM. Do drugs affect the risk of hip fracture in elderly women? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:1006–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk in patients treated with loop diuretics. J Intern Med. 2006;259:117–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carbone LD, Johnson KC, Bush AJ, Robbins J, Larson JC, et al. Loop diuretic use and fracture in postmenopausal women: findings from the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:132–140. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:144–153. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez LAG, Cea-Soriano L, Ruigomez A, Johansson S. A UK Primary Care Study on Acid-Supressive Drugs and Hip Fracture: is there a link? GUT. 2012;60(Supplement 3) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiens M, Etminan M, Gill SS, Takkouche B. Effects of antihypertensive drug treatments on fracture outcomes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Intern Med. 2006;260:350–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aung K, Htay T. Thiazide diuretics and the risk of hip fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD005185. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005185.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomon DH, Mogun H, Garneau K, Fischer MA. Risk of fractures in older adults using antihypertensive medications. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1561–1567. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry SD, Mittleman MA, Zhang Y, Solomon DH, Lipsitz LA, et al. New loop diuretic prescriptions may be an acute risk factor for falls in the nursing home. Pharm Drug Saf. 2012;21:560–563. doi: 10.1002/pds.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudy DW, Voelker JR, Greene PK, Esparza FA, Brater DC. Loop diuretics for chronic renal insufficiency: a continuous infusion is more efficacious than bolus therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:360–366. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gribbin J, Hubbard R, Gladman J, Smith C, Lewis S. Risk of falls associated with antihypertensive medication: self-controlled case series. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:879–884. doi: 10.1002/pds.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517–522. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyberg L, Gustafson Y, Berggren D, Brannstrom B, Bucht G. Falls leading to femoral neck fractures in lucid older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:156–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klungel OH, Martens EP, Psaty BM, Grobbee DE, Sullivan SD, et al. Methods to assess intended effects of drug treatment in observational studies are reviewed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sennerby U, Melhus H, Gedeborg R, Byberg L, Garmo H, et al. Cardiovascular diseases and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2009;302:1666–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]