Abstract

Myotubular myopathy is a subtype of centronuclear myopathy with X-linked inheritance and distinctive clinical and pathologic features. Most boys with myotubular myopathy have MTM1 mutations. In remaining individuals, it is not clear if disease is due to an undetected alteration in MTM1 or mutation of another gene. We describe a boy with myotubular myopathy but without mutation in MTM1 by conventional sequencing. Array-CGH analysis of MTM1 uncovered a large MTM1 duplication. This finding suggests that at least some unresolved cases of myotubular myopathy are due to duplications in MTM1, and that array-CGH should be considered when MTM1 sequencing is unrevealing.

Keywords: Myotubular myopathy, Congenital myopathy, MTM1, Gene duplication, Diagnostic testing

1. Introduction

Centronuclear myopathies (CNMs) are a group of congenital myopathies characterized by hypotonia, proximal weakness, ophthalmoparesis, ptosis, and respiratory insufficiency [1,2]. Onset is variable from birth to adulthood. Several inheritance patterns have been described including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and X-linked. Diagnosis is typically based on pathological features and molecular genetic testing. The most prominent pathologic feature is centrally placed nuclei [3,4]. Other, more variable, pathologic features typically include type I fiber predominance, myofiber hypotrophy, increased connective tissue and fibro-adipose replacement. Currently, mutations in four genes are associated with CNM: dynamin-2 (DNM2) [5], ryanodine receptor (RYR1) [6], amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) [7] and myotubularin (MTM1) [8]. Mutations in MTM1 are specifically associated with myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a subtype of centronuclear myopathy with X-linked inheritance and some distinctive clinical features.

Typically, the most severe cases of CNM have been associated with MTM1 mutations [1] or occasional rare mutations of RYR1 or BIN1 [6,7]. Over 200 different disease- causing mutations have been identified in MTM1 including missense, nonsense, intronic, small deletions/ duplications and large rearrangements [8–22]. While MTM1 mutations have been identified in the vast majority of patients with a consistent clinical and histopathologic history, 10% of males with a suspected diagnosis of myotubular myopathy remain genetically unresolved [23], suggesting either additional genetic causes for myotubular myopathy or that MTM1 mutations in some individuals are not recognized by conventional diagnostic techniques. A recent case report by Trump and colleagues [9], described a patient with a severe presentation of CNM. Routine sequencing did not identify a pathogenic mutation in MTM1. MLPA analysis was performed and identified a duplication of exon 10. This report emphasizes the importance of screening for complex rearrangements in MTM1. In the current study, we report a patient with a severe presentation of CNM due to a large duplication in MTM1, suggesting that analysis for MTM1 deletions and duplications should be carried out in cases of suspected myotubular myopathy where conventional sequencing does not detect a mutation.

2. Case report

This male patient was born at 33 4/7 weeks by C-section for a breech position. Birth weight was 1890 grams (10th – 25th percentile) and length was 49.5 cm (97th percentile). During the pregnancy, the mother reported reduced fetal movements, though all prenatal ultrasounds were normal. At birth, the patient was hypotonic and was in respiratory distress. CPAP was used initially, but at 4 days of age the patient was intubated.

In terms of motor function, at one day of age the patient was able to move his hands; at one week, he was able to move all limbs. Weakness of the neck and extra-ocular muscles was noted on exam. Difficulties swallowing and excessive secretions led to the placement of a naso-gastric tube. The patient passed away at 8 weeks of age due to acute respiratory failure.

No family history of neuromuscular diseases was reported. The initial diagnostic workup consisted of chromosomal analysis and molecular testing for myotonic dystrophy type I, both of which were negative. These tests were followed by a muscle biopsy and additional molecular testing.

2.1. Pathologic findings

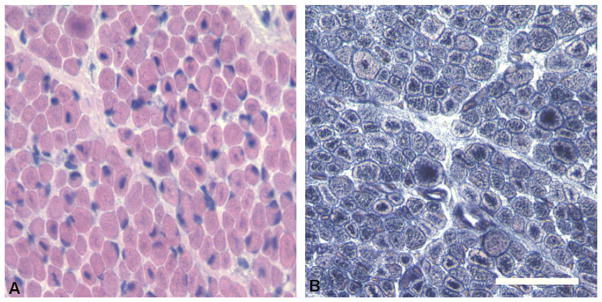

The patient underwent muscle biopsy of the right thigh at 6 weeks of age. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of muscle biopsy tissue revealed uniformly small myofibers and a numerous fibers containing large, centrally located nuclei (Fig. 1). Some fibers contained central areas with either excessive basophilic staining or clearing of the cytoplasm, which corresponded to aggregates of organelles on histochemical stains for reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and cytochrome oxidase (COX). No spoked-wheel structures were seen on NADH stain. Central nuclei were found in both fiber types, and there was no evidence of grouping or other fiber type-specific changes on ATPases at pH 4.3 and 9.8. Dystrophin antibodies showed no abnormalities. Overall, the presence of small myofibers, markedly increased numbers of fibers with large, central nuclei, and central accumulations of organelles was highly consistent with a pathological diagnosis of XLMTM or severe CNM.

Fig. 1.

Pathological findings on muscle biopsy. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of frozen muscle tissue reveals small round myofibers and numerous fibers containing large, centrally placed nuclei. Central areas with clear or basophilic staining are present within many fibers, which contain aggregates of mitochondria and other organelles, and are best visualized on NADH staining (B). Bar = 50 mm.

2.2. Molecular analyses

Molecular genetic testing for several causes of CNM was performed. This included conventional sequencing from genomic DNA (i.e. Sanger sequencing of all coding exons as well as all intron–exon boundaries) of MTM1, DNM2 and RYR1. No pathogenic mutations were detected in any of the 3 genes. Research based whole exome sequencing also failed to detect any mutations in these three genes as well as in BIN1. Since the patient’s symptoms and biopsy findings were strongly suggestive of XLMTM, we pursued additional testing of MTM1.

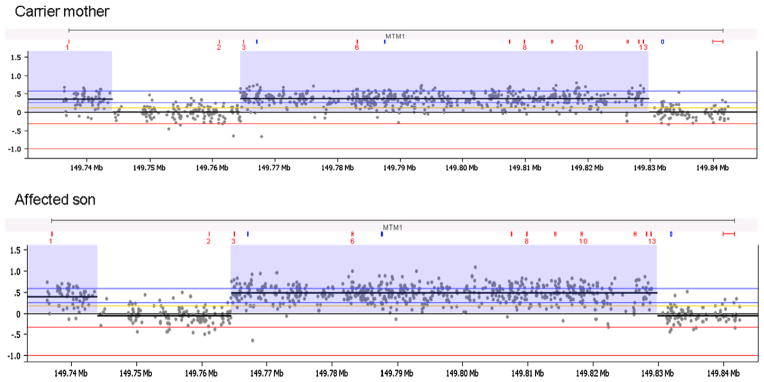

Deletion and duplication testing of the MTM1 gene was performed on the patient and his mother using a custom high resolution, targeted 8 × 60 K array-CGH platform containing the MTM1 gene and an additional 44 genes (Agilent Technologies). A total of 965 probes spanning the MTM1 gene and flanking regions were present on this custom array. All experimental procedures were conducted using the manufacture recommended protocol. Microarray data was analyzed using the Nexus software (BioDiscovery, El Segundo, CA) for copy number analysis. This analysis identified a previously unreported duplication of MTM1 in the patient and his mother. The duplication appeared to be complex with a large duplicated region involving MTM1 exons 1 (chrX: g.(?_149,736,384)_(149, 743,600_149,744,456)dup [hg19]), 3–13 (chrX:g.(149,764,500_149,764,537)_(149,828,980_149, 830,745)dup [hg19]) interrupted by a non-duplicated region involving exon 2 (Fig. 2). The last two coding exons of the MTM1 gene (exons 14 and 15) were also not involved in this rearrangement. This duplication is predicted to affect the production of a normal MTM1 transcript.

Fig. 2.

Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) results for MTM1. Deletion and duplication testing of the MTM1 gene locus was performed using a custom designed 8 × 60 K array-CGH platform (Agilent Technologies) that contained probes for 45 genes including MTM1. Analysis of genomic DNA of the affected male patient and his mother revealed a duplication of the MTM1 gene involving exons 1, 3–13 and no duplication of exons 2, 14 and 15. Regions of MTM1 copy number gains are highlighted in purple and evidenced by the elevated log2 fluorescence ratios. Each dot shows a log2 ratio of the hybridization signals of patient versus gender-match control for each probe in the MTM1 gene. The positions of the MTM1 exons are indicated in red above each aCGH chart. The x and y axes represent genomic coordinates and the log2 hybridization signals, respectively.

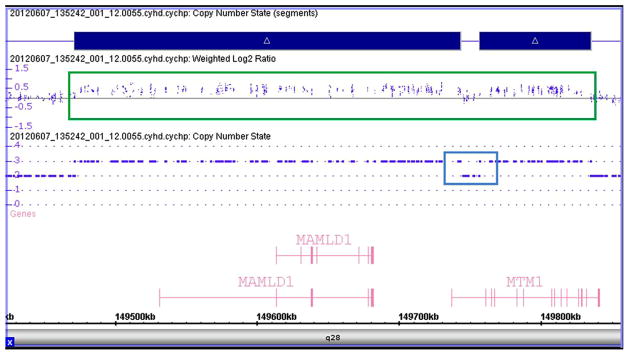

To better define the proximal end of the duplication upstream of MTM1 exon 1, SNP array analysis of the mother’s sample was performed using the CytoScan HD Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The CytoScan HD Array is a whole-genome array containing over 2.6 million markers, including 750,000 SNPs. SNP array analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Results were processed and visualized using Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) 1.2.3 software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). An interstitial duplication of the long arm of chromosome X in the cytogenetic band position Xq28 was observed (arrXq28(149,474,705–149,830,745)x3 [hg19]). The duplication spanned approximately 356 kb and was interrupted by a non-duplicated region, confirming the finding on the MTM1 targeted array-CGH. The duplication involved the MTM1 gene, excluding its terminal end, and the entire proximal MAMLD1 gene (MIM 300120) (Fig. 3). Of note, the duplication was not identified in the whole exome sequencing data.

Fig. 3.

SNP array results for MTM1 duplication. SNP array was performed to define the proximal end of the MTM1 gene duplication using the Affymetrix CytoScan HD Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Analysis using the ChAS software showed a 356 kb duplication that includes the MTM1 and MAMLD1 genes in the patient’s mother, and was detected as an increase in the weighted log2 ratio and copy number state. Duplicated probes are shown within the green box, while probes in this region with a normal copy number are shown within the blue box.

To further investigate the potential effect of the duplication on MTM1, we examined RNA isolated from skin fibroblasts from the proband’s mother. RT-PCR analysis was performed using different combinations of primers designed at the distal end of the duplication under the assumption that the repeated copy was arranged in tandem. This included multiple forward primers in exon 13 and reverse primers in exons 2 and 3. This analysis failed to identify the position of this breakpoint under the above assumption. This is consistent with either further complexity of this rearrangement or instability of the duplicated transcript.

3. Discussion

This report reinforces the importance of complete testing of MTM1 as previously suggested by Trump and colleagues [9]. For those patients where sequencing of MTM1 is negative, but the diagnosis is strongly suspected, it is important to pursue testing for intronic mutations (via RT-PCR and/or Western blot analysis) and for large rearrangements (deletions/duplications, tested via array-CGH or MPLA) of the gene. The value of confirming this specific diagnosis is many fold. Myotubular myopathy due to MTM1 mutation carries a risk of non-muscle related phenotypes not reported in other CNMs that include pyloric stenosis, spherocytosis, gallstones, kidney stones or nephrocalcinosis, a vitamin K-responsive bleeding diathesis, hepatic peliosis, and liver dysfunction manifested by pruritus and elevated serum transaminases [22]. Additionally, the implications for familial inheritance and genetic counseling are important since this is an X-linked condition whereas all other CNMs have been found to have an autosomal inheritance pattern.

The duplication identified in this report includes MTM1 and MAMLD1. A previous report described a patient with a deletion of these genes with a phenotype consistent with XLMTM and genital abnormalities [24], though not all patients with deletions of these genes have the genital phenotype (potentially as a result of an MTMR1–MAMLD1 fusion transcript) [15]. While the patient in this report did not have any genital abnormalities, this is perhaps not surprising, as a duplication of the MAMLD1 gene would not necessarily be predicted to result in genital abnormalities, and to date only loss function mutations/ deletions of the MAMLD1 gene have been associated with hypospadias – OMIM #300758 [25]). Additionally, the mechanism leading to the duplication and how it affects gene function are unclear at this time.

In terms of the MTM1 duplication itself, our prediction is that it results in a non-functional MTM1 transcript. The fact that exon 2 is not duplicated would indicate that the resulting transcript should produce an out-of-frame coding sequence and a premature stop codon. Such a transcript is likely to be degraded by nonsense-mediated decay mechanisms and not translated into MTM1 protein. This assertion is supported by our data, where we were unable to detect any of the abnormal transcript from total RNA isolated from fibroblasts from the mother. However, there was insufficient remaining sample from the proband’s biopsy to definitely demonstrate the absence of either MTM1 transcript or MTM1 protein.

In summary, we present a case study of a male infant with a clinical history consistent with myotubular myopathy and with a large duplication at the MTM1 gene locus. This study emphasizes the utility of duplication testing by MPLA or array-CGH in situations where MTM1 mutation is suspected by not detected by conventional gene sequencing.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the family and their participation in this study and to Elizabeth DeChene, M.S., C.G.C. for assistance in ascertainment and enrollment of this patient. JJD is supported by NIH K08 AR054835, MDA186999, and the Taubman Medical Institute. AHB is supported by NIH R01 AR044345, MDA 201302, and the Lee and Penny Anderson Family Foundation. MWL is supported by K08 AR059750 and L40 AR057721. The authors all gratefully acknowledge the continued support for research into the congenital myopathies by the Joshua Frase Foundation.

References

- 1.Jungbluth H, Wallgren-Pettersson C, Laporte J. Centronuclear (myotubular) myopathy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero NB, Bitoun M. Centronuclear myopathies. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2011;18(4):250–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero NB. Centronuclear myopathies: a widening concept. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(4):223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierson CR, Tomczak K, Agrawal P, Moghadaszadeh B, Beggs AH. X-linked myotubular and centronuclear myopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(7):555–64. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000171653.17213.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitoun M, Maugenre S, Jeannet PY, et al. Mutations in dynamin 2 cause dominant centronuclear myopathy. Nat Genet. 2005;37(11):1207–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilmshurst JM, Lillis S, Zhou H, et al. RYR1 mutations are a common cause of congenital myopathies with central nuclei. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(5):717–26. doi: 10.1002/ana.22119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicot AS, Toussaint A, Tosch V, et al. Mutations in amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) disrupt interaction with dynamin 2 and cause autosomal recessive centronuclear myopathy. Nat Genet. 2007;39(9):1134–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laporte J, Hu LJ, Kretz C, et al. A gene mutated in X-linked myotubular myopathy defines a new putative tyrosine phosphatase family conserved in yeast. Nat Genet. 1996;13(2):175–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trump N, Cullup T, Verheij JB, et al. X-linked myotubular myopathy due to a complex rearrangement involving a duplication of MTM1 exon 10. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(5):384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McEntagart M, Parsons G, Buj-Bello A, et al. Genotype–phenotype correlations in X-linked myotubular myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(10):939–46. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biancalana V, Caron O, Gallati S, et al. Characterisation of mutations in 77 patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy, including a family with a very mild phenotype. Hum Genet. 2003;112(2):135–42. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0869-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laporte J, Biancalana V, Tanner SM, et al. MTM1 mutations in X-linked myotubular myopathy. Hum Mutat. 2000;15(5):393–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200005)15:5<393::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanner SM, Schneider V, Thomas NS, et al. Characterization of 34 novel and six known MTM1 gene mutations in 47 unrelated X-linked myotubular myopathy patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 1999;9(1):41–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(98)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herman GE, Kopacz K, Zhao W, et al. Characterization of mutations in fifty North American patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy. Hum Mutat. 2002;19(2):114–21. doi: 10.1002/humu.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai TC, Horinouchi H, Noguchi S, et al. Characterization of MTM1 mutations in 31 Japanese families with myotubular myopathy, including a patient carrying 240 kb deletion in Xq28 without male hypogenitalism. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15(3):245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flex E, De Luca A, D’Apice MR, et al. Rapid scanning of myotubularin (MTM1) gene by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(5):501–5. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schara U, Kress W, Tucke J, Mortier W. X-linked myotubular myopathy in a female infant caused by a new MTM1 gene mutation. Neurology. 2003;60(8):1363–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058763.90924.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertini E, Biancalana V, Bolino A, et al. 118th ENMC International workshop on advances in myotubular myopathy, 26–28 September 2003, Naarden, The Netherlands (5th Workshop of the international consortium on myotubular myopathy) Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14(6):387–96. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laporte J, Guiraud-Chaumeil C, Vincent MC, et al. Mutations in the MTM1 gene implicated in X-linked myotubular myopathy. ENMC International Consortium on Myotubular Myopathy European Neuro-Muscular Center. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(9):1505–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Gouyon BM, Zhao W, Laporte J, et al. Characterization of mutations in the myotubularin gene in twenty six patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(9):1499–504. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosch V, Vasli N, Kretz C, et al. Novel molecular diagnostic approaches for X-linked centronuclear (myotubular) myopathy reveal intronic mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(6):375–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herman GE, Finegold M, Zhao W, de Gouyon B, Metzenberg A. Medical complications in long-term survivors with X-linked myotubular myopathy. J Pediatr. 1999;134(2):206–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laporte J, Kress W, Mandel JL. Diagnosis of X-linked myotubular myopathy by detection of myotubularin. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(1):42–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laporte J, Kioschis P, Hu LJ, et al. Cloning and characterization of an alternatively spliced gene in proximal Xq28 deleted in two patients with intersexual genitalia and myotubular myopathy. Genomics. 1997;41(3):458–62. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukami M, Wada Y, Miyabayashi K, et al. CXorf6 is a causative gene for hypospadias. Nat Genet. 2006;38(12):1369–71. doi: 10.1038/ng1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]