Abstract

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and GLP-1 analogs have received much recent attention due to the success of GLP-1 mimetics in treating type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM), but these compounds may also have the potential to treat obesity. The satiety effect of GLP-1 may involve both meal entero-enteric reflexes and across meal central signaling mechanisms to mediate changes in appetite and promote satiety. Here, we review the data supporting the role of both peripheral and central GLP-1signaling in the control of gastrointestinal motility and food intake. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the appetite suppressive effects of GLP-1 may help in developing targeted treatments for obesity.

Keywords: GLP-1, appetite, gastrointestinal motility, food intake

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) has been the focus of much research because of the success of GLP-1 mimetics in treating T2DM, acting as incretins (see glossary) in the pancreas. It is becoming clear that GLP-1 may also have potential for the treatment of obesity. GLP-1 or its synthetic analogues, exendin 4 (Ex 4) and liraglutide, are potent inhibitors of food intake in both animal models and human subjects. Thus, understanding the mechanisms underlying the appetite suppressive effects of GLP-1 may help in developing targeted treatments for obesity.

GLP-1 biology and physiological properties

GLP-1 is derived from the proglucagon gene, which in the gastrointestinal tract and brain is post-translationally modified and cleaved into the biologically active forms, GLP-1 (7-36) amide and GLP-1 (7-37) 1. The major circulating bioactive species in humans is the truncated form GLP-1 (7-36) amide 2. The hormone has been identified as playing a prominent role in glucose homeostasis, gastrointestinal motility, appetite and additional roles beyond ingestive behaviors 3–5.

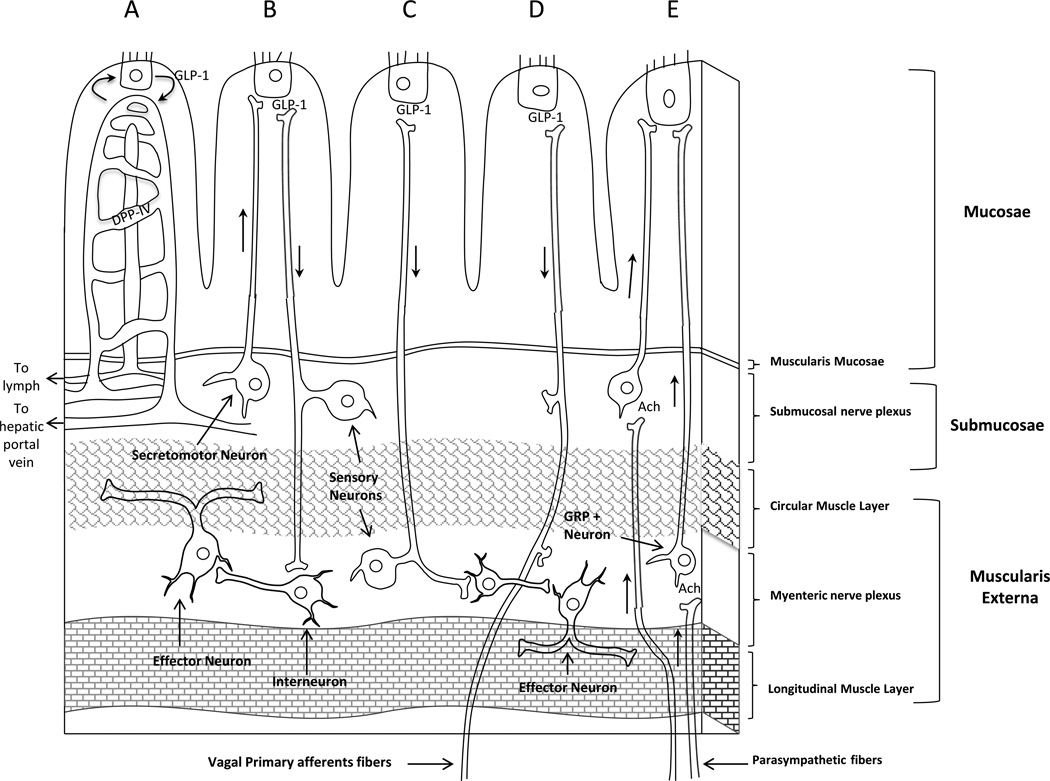

GLP-1 is secreted from mucosal endocrine L cells of the intestine in response to intraluminal nutrients, but non-nutrient driven increases in GLP-1 also have been reported such as cephalic6 and meal anticipatory increases 7. With regards to nutrients, there are two peaks in GLP-1 secretion that are seen in response to a meal in humans 8. The first peak appears within 15 min after meal initiation before nutrients may even access the L-cells lower in the intestine. This rapid rise in GLP-1 levels appears to involve a neuroendocrine loop where nutrients in the stomach or proximal intestine stimulate the release of hormones, such as gastric inhibitory peptide 9 and gastrin-releasing peptide 10, that act through vagal pathways to stimulate L cells to secrete GLP-1 11 (Figure 1E). The enteric nervous system may contribute to this early GLP-1 rise after a meal 11 (Figure 1B). The second peak occurs later, is larger, and is thought to derive from direct nutrient contact with intestinal L cells. Thus, nutrients within the gastrointestinal tract have the ability to stimulate GLP-1 directly and indirectly through hormonal and neural mechanisms.

Figure 1. GLP-1 action in the gut.

(A) GLP-1 released from the L cells diffuses into the lamina propria and enters the lymph or capillaries. DPP-IV is expressed in the capillaries and can immediately begin to degrade GLP-1 before it even reaches the hepatic portal vein. GLP-1 released from the L cell can mediate changes in the submucosal (B) and myenteric nerves (C). (D) GLP-1 can have a direct effect on vagal primary afferents. (E) Luminal nutrients in the proximal GI tract may stimulate distal GLP-1 secretion through an enteroendocrine loop that involves vagal and enteric neural connections. Hormones released from the stomach or proximal intestine stimulate vagal pathways that synapse on GRP neurons in the myenteric plexus to cause downstream stimulation of GLP-1 fom the L cell in the mucosal epithelium.

Ach: acetylcholine, GRP: gastrin-releasing peptide, DPP-IV: dipeptidyl peptidase-4, GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide-1.

GLP-1 is also expressed by neurons within the nucleus of the solitary tract of the brainstem (NTS) and is released from terminals across a variety of brain areas including hypothalamic nuclei and hippocampal and cortical sites 12. Central GLP-1 appears to be an important link in the downstream mediation of anorexia produced by a number of factors. Stimulation of the endogenous caudal brainstem GLP-1 activity has been implicated in the mediation of the anorexic effect of lipopolysacharide (LPS; 13, 14), lithium chloride (LiCl; 14, 15), cholecystokinin (CCK; 14) leptin 16 and oxytocin 17. Many of these factors administered to rodents at doses that decrease food intake, increase c-fos expression in GLP-1 neurons 14 and the anorexic effects are attenuated or eliminated with central injection of a GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) antagonist 13, 15, 17. The central GLP-1 pathway involved in reducing appetite may involve some of the same neural circuits known to be involved in ingestive behaviors because GLP-1 fibers are found within these brain sites 12 and GLP-1 actively binds to receptors in these same areas 18, 19. However, there does appear to be a mismatch between the density of GLP-1 nerve fibers and GLP-1 receptors. There are few GLP-1 nerve fibers present in some brain nuclei where GLP-1 binding is high 12, a finding that suggests a role for peripheral GLP-1 in the central GLP-1 receptor activation.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor

The actions of GLP-1 are mediated by the activation of a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R). GLP-1R is a G-protein coupled receptor that is expressed throughout the periphery (ie. enteric nerves, vagal nerves, pancreas, stomach, small and large intestine and adipose tissue 20–22) and brain (ie. caudal brainstem, hypothalamic, hippocampal, cortical nuclei 12, 23). It is still not completely clear if peripheral GLP-1 acts locally to alter gastrointestinal motility and appetite, or if GLP-1 can directly activate brain GLP-1R to modulate these functions/behaviors. Endogenous GLP-1 released from the L cells diffuses into the lamina propria and enters the lymph or capillaries 24 (Figure 1A). Once GLP-1 enters the capillaries, it is rapidly degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), an enzyme expressed on the capillary walls 25 and throughout the body 26, 27. It has been estimated that only 25% of the absorbed GLP-1 reaches the liver through the hepatic portal vein26. It is possible, though, that GLP-1 could act on GLP-1R on vagal afferents in the lamina propria or enteric nerves in the intestinal wall, before entering the capillaries 22, 28 (Figure 1B,C and D). It also may be possible that greater and longer increases in GLP-1 could saturate the available DPP-IV and allow for more GLP-1 to enter into general circulation. This idea is supported by an accumulation of evidence showing that mRNA expression or blood levels of DPP-IV are altered under a variety of conditions and, thus, could be a mechanism by which greater GLP-1R stimulation could occur throughout the body 29–31. If GLP-1 survives degradation from DPP-IV, it is possible that it could activate central GLP-1R, because circulating GLP-1 appears to pass the blood brain barrier by simple diffusion to circumventricular organs 32 and elsewhere 33. As mentioned above, peripheral GLP-1 activation of central receptors appears likely because there are few GLP-1 nerve fibers present in feeding related brain nuclei such as the arcuate nucleus12, where GLP-1 binding is high 18, 19. It has also been suggested that there are regional differences in DDP-IV present in rat cerebral capillaries that could account for a more precise control of brain access of peripherally derived GLP-1 33.

GLP-1 and gastrointestinal motor functions

One mechanism by which GLP-1 can alter appetite is through changes in gastrointestinal function. GLP-1 decreases gastric emptying and intestinal motility 34, 35 and contributes to the ileal break 36, an inhibitory feedback mechanism that functions to optimize nutrient digestion and absorption. GLP-1 appears to affect gastrointestinal motor functions through both peripheral and central nervous system mechanisms. Vagal-mediated pathways have been shown to participate in the attenuation of gastric motility and emptying induced by GLP-1 in non-human animal models 37, 38 and in intestinal motility in humans 34. Interactions with brain GLP-1R may also contribute to these changes because intracerebroventricular (icv) injection of GLP-1 inhibits gastric emptying through non-cholinergic and non-adrenergic pathways in rats 37. A third, more direct route of GLP-1 mediated changes in motor function can occur through GLP-1R activation in enteric neurons in the gastrointestinal wall. GLP-1R immunoreactivity is present on myenteric neurons and a few submucosal neurons of the duodenum and proximal colon in mice 28. In mouse intestinal explants, the hormone was found to inhibit intestinal motility through direct interaction and activation of GLP-1R, in enteric neurons 28. More specifically, GLP-1 appears to inhibit evoked activity (provided by electrical field stimulation on parallel sides of intestinal segments from mice) in the circular muscle of the intestine by modulating parasympathetic cholinergic input presynaptically 28. GLP-1 administered intra-arterially in an ex vivo canine prep also inhibits evoked activity of the circular muscle and this response is blocked by a GLP-1 receptor antagonist, exendin-9 (Ex 9) 39. Conversely, GLP-1 does not affect spontaneous circular muscle activity or evoked or spontaneous activity in the longitudinal muscle28, 40. Taken together, these results suggest that GLP-1 may modulate neural input to the circular, but not the longitudinal, muscle layer and are consistent with the notion that the circular muscle layer contraction is dominant in peristalisis. These results also show that GLP-1 may only inhibit evoked, but not spontaneous, neural action on motility. This finding may provide insight into the mechanisms underlying the ability of GLP-1to inhibit gastrointestinal function only in normal, but not vagotomized patients 41. Much of the neural stimulation of the gut wall is provided by the parasympathetic fibers of the vagus nerve and severing this connection would block electrical stimulation of the circular muscle of the intestine. Since the role of GLP-1 appears to be to modulate cholinergic stimulation of the circular muscle, an attenuated response to GLP-1 in vagotomized human patients would be expected.

In contrast to the inhibitory effect of GLP-1 in the stomach and small intestine, GLP-1 increases colonic transit and this effect may be mediated through a central mode of action 42, 43. Indeed, icv, but not intraperitoneal (ip), injections of GLP-1 dose-dependently accelerate colonic transit 44. The central GLP-1 effect on colonic transit was attenuated by methods that blocked the parasympathetic nervous system, such as vagotomy, use of the competitive antagonist for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor atropine, or the ganglionic blocker hexamethonium, but not the sympathetic nervous system (ie. guanethidine) 44. Cholinergic stimulation enhances colonic motor activity and transit in humans 45, thus, GLP-1 may act within the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus to mediate changes in the parasympathetic innervation to alter motor contractions in the colon.

GLP-1 and satiety

Peripheral action of GLP-1 in reducing food intake

GLP-1 decreases food intake after peripheral (ip) 46, intravenous 47 48, 49 and central administration (icv) 50, 51, but the relative roles of peripheral and central GLP-1R in the actions of endogenous intestinal GLP-1 remain to be clarified. The story is complicated by the fact that many of the studies investigating the action of GLP-1 use ip or iv administration of the GLP-1 synthetic analogues Ex 4 or liraglutide, which escape the degradation of DPP-IV and are able to cross the blood brain barrier 47, 52. Thus, the effectiveness of these GLP-1R agonists may depend in part on an enhanced ability to access additional GLP-1R, compared with endogenously released or exogenously administered GLP-1. There is some evidence, though, to support a peripheral action of GLP-1 in reducing food intake. For example, central administration of the GLP-1R antagonist Ex 9 is not able to block the decreases in food intake produced after peripheral administration of GLP-1, but is able to block decreases in food intake after central injection of GLP-1 53. Ex 9 administered peripherally is also able to block decreases in food intake after a nutrient preload and a peripheral GLP-1 injection 53. These data suggest that the satiety actions of intestinally derived GLP-1 are through peripheral receptors.

It is not clear where in the periphery GLP-1 may be acting to decrease appetite. The rapid degradation of GLP-1 that occurs soon after release into the capillaries of the intestinal wall, supports the notion that GLP-1 may act locally on enteric or vagal neurons. The results from studies using varying routes of administration of GLP-1 do not clearly support this idea, though. The decreases in food intake after ip GLP-1 in rats 54 and Ex-4 in mice 55 are attenuated by complete sub-diaphragmatic vagotomy or by capsaicin administration (a procedure that lesions sensory nerves), respectively. When GLP-1 is infused in rats at the onset of the first spontaneous dark-phase meal (a model that may mimic the initial meal-induced secretion of GLP-1 from the intestine), decreases in food intake occurred after hepatic portal vein (HPV), vena cava (vc) and ip infusions of GLP-1 56. Sub-diaphragmatic vagal deafferentation attenuates the decrease in food intake after ip GLP-1 infusion, but not after HPV GLP-1 infusions 56. Moreover, the effect of iv infusion of GLP-1 to reduce sucrose intake was not abolished by capsaicin treatment or vagotomy 57. Thus, the satiating effect of ip, but not HPV or iv GLP-1, requires vagal afferent signaling. The different findings with different routes of administration suggest that in each case GLP-1 could be binding to different GLP-1R populations, even though each is producing a decrease in food intake after administration. It is possible that only ip, and not HPV, vc or iv, infusion of GLP-1 may be able to access the GLP-1R on enteric or vagal nerves of intestinal origin that are normally and immediately accessible to endogenous GLP-1 released from intestinal L cells. HPV, vc and iv infusions of GLP-1 could mimic endogenous circulating GLP-1 if enough GLP-1 is able to escape degradation from DPP-IV in the capillaries of the intestine and enter the HPV and systemic circulation, at each step encountering more DPP- IV. Thus, just where in the periphery GLP-1 acts to inhibit feeding behavior remains unresolved. A study that investigates whether local administration of Ex 9 in the intestinal wall increases food intake would prove useful in defining the role of local GLP-1R.

Central action of GLP-1 in reducing food intake

Central mechanisms are certainly important in the mediation of the satiety actions of both peripheral and central GLP-1. Even if peripheral GLP-1 acts locally on enteric or vagal neurons, the downstream neural or hormonal responses must activate many brain circuits to affect food intake. For example, lesions of the projections from the brainstem to the hypothalamus reduce the appetite suppression mediated by peripheral GLP-1 in rats 54. Even though peripheral and central GLP-1 utilizes brain mechanisms to inhibit feeding, some differing neural substrates appear to be involved. Both peripheral and central injections of GLP-1 induce cfos in the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus (PVN), but only central and not peripheral GLP-1 injection induces cfos in the Arc 58, suggesting differential mechanisms underlying the ability of central versus peripheral GLP-1 in decreasing appetite.

Central injections of GLP-1 inhibit food intake 50, 51 and this central effect does not require the presence of food in the stomach or an inhibition of gastric emptying 59. The caudal brainstem appears to be sufficient in mediating GLP-1-induced decreases in food intake. Ip or 4th ventricular Ex-4 are still able to decrease intake in chronic supracollicular decrebrate rats 60. Only a 4th ventricular injection of Ex-9, not a forebrain injection with aquaduct occlusion, blocked the decreases in food intake induced by LPS administration 13. Moreover, 4th ventricular injection of Ex-9 prior to 4th ventricular leptin administration attenuates the inhibitory effect of leptin. Co-administration of Ex-4 and leptin into the 4th ventricle suppresses food intake in an additive manner 16. Within the brainstem, leptin receptors are exclusively expressed within the medial NTS and the medial NTS has been suggested as the main site of action for GLP-1 16, 61. This would mean that the central endogenous GLP-1 produced exclusively in the NTS, might act on GLP-1R within the same nuclei. Such a local feedback loop may play defined roles in satiety, but this is only part of an integrated process that also involves forebrain processing.

Endogenous brainstem GLP-1 and feeding control

A role of endogenous brainstem GLP-1 in overall feeding control is supported by data showing that knockdown of the proglucagon gene in the NTS using RNA interference, results in hyperphagia and weight gain 62. NTS GLP-1 neurons project widely throughout the brain and, thus, this food intake and body weight response could be mediated by multiple neural circuits. Sandoval et al. 63 have demonstrated that GLP-1 administration into the Arc affected glucose metabolism and insulin release, while PVN GLP-1 reduced food intake. Many others, though, have provided evidence that the Arc does play a role in GLP-1 mediated anorexic effects. This discrepancy may result from differences in the methods for manipulating GLP-1 signaling in the Arc, and if it was targeting both orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons or differentiating between the two.

Arc orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons are known to respond to many ingestive signals, including GLP-1. Receptors for GLP-1 are present on the orexigenic neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide (NPY/AgRP) neurons, and the anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, and icv injections of GLP-1 induces cfos immunoreactivity within the Arc 64. Seo et al., 65 found that icv injection of GLP-1 at doses that decrease fasting induced feeding, attenuates fasting induced increases in NPY and AgRP mRNA levels, and decreases in POMC and CART mRNA levels. In the Arc, fasting induced increases in AMP-activated kinase α2 (AMPKα2) mRNA levels and phoshorylation of AMPKα and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) are also attenuated by icv GLP-1 65. These data suggest that NTS-GLP-1 projections to the Arc could mediate satiety by affecting both orexigenic and anorexigenic signaling. Further data, though, have suggested that GLP-1 actions are mediated through the anorexigenic component and not the orexigenic one. Icv injections of GLP-1 in fasted or ad libitum fed rats did not alter Arc NPY expression levels 50. Ex-4 administration also failed to alter hypothalamic NPY gene expression 66. In addition, responses to central GLP-1 remain after NPY/AgRP neurons are destroyed by lesions induced by saporin, a ribosomal inactivating toxin conjugated to NPY (NPY-SAP) 67. Although GLP-1 may not directly decrease Arc NPY mRNA levels to induce satiety, GLP-1R signaling may still affect NPY signaling. If GLP-1R is blocked by icv administration of Ex-9, prior to icv injection of NPY, there is a significant increase in food intake beyond that with NPY alone 50. Along these lines, the contribution of POMC neurons in producing anorexia under a variety of stimuli has been well documented and involves POMC projections to other brain sites expressing melanocortin receptors. POMC neurons project to the NTS 68 where GLP-1 producing cells are located and may be a component of a forebrain- brainstem circuit in which a variety of signals interact with GLP-1 signaling. Arc POMC cells also project to melanocortin receptor expressing cells within the PVN 68, suggesting a circuit where GLP-1 may indirectly affect PVN mediated decreases in food intake.

There are direct, reciprocal neural connections between the PVN and NTS which allow for an additional integration of anorexic signals with GLP-1 signaling 68. GLP-1 producing neurons of the NTS have strong projections to GLP-1R expressing cell bodies in the PVN 14 and central GLP-1 activates oxytocin (OT) and corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) neurons within the PVN 64. OT neurons express GLP-1R and the anorexigenic effect of OT is eliminated in rats injected in the 3rd ventricle with GLP-1R antagonist, but an OT antagonist does not block the anorexigenic effect of GLP-1 17. This suggests that NTS GLP-1 producing cells may act through OT GLP-1R positive cells to alter OT cell signaling or OT release. GLP-1 also activates the HPA axis through CRH neurons 69 and GLP-1 positive nerve terminals densely innervate CRH neurons 70. Thus, GLP-1 mediated decreases in food intake may be at least partially mediated by activation of the stress axis. CRH neuronal activity is essential for LPS induced decreases in food intake and may utilize this additional hypothalamic-brainstem circuit to activate NTS GLP-1 neurons 71. Thus, the satiety effects of GLP-1 may be mediated by both hypothalamic Arc and PVH connections to brainstem.

GLP-1 neurons in the NTS also project directly to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) 72 and nucleus accumbens 37 core and shell 72, 73, nuclei involved with food reward that have also been demonstrated to express GLP-1R. GLP-1 or Ex-4 injected into the VTA and NAc core, decrease food intake of rats on chow, high-fat diet, or sucrose solution 72, 73. Dissimilar effects of GLP-1 are found in the NAc core versus the shell. Ex-4 injected into the NAc shell was also able to decrease high-fat food intake, but Ex-4 and GLP-1 had no effect on intake of chow or sucrose solution 72, 73 at this site. In each case where there was a decrease in food intake with agonist administration, a GLP-1 antagonist was able to induce an increase in chow, high-fat diet, or sucrose solution intake. These data suggest a role for endogenous GLP-1R in the VTA and NAc in mediating satiety and that this effect may be due to modifying reward signaling.

GLP-1 and conditioned taste aversion

A concern about the specificity of the feeding inhibitory actions of GLP-1 has arisen due to the idea that the decreases in food intake after treatment with GLP-1 or a synthetic analogue are attributable to visceral illness or feelings of nausea 74. GLP-1 is able to induce a conditioned taste aversion (CTA) under a variety of conditions, but the satiety and CTA effects appear to be nuclei specific 74. Lateral and fourth ventricle injections of GLP-1 in rats decreased food intake similarly, but only lateral ventricle GLP-1 injections produced CTA 75. Furthermore, direct injections of GLP-1 into the PVN decreases food intake without a CTA 76. In contrast, the typical CTA response after LiCl administration is attenuated by bilateral injections of a GLP-1R antagonist into the central nucleus of the amygdala 29 75. These data suggest that the illness response to GLP-1 may be dependent on discrete receptors outside of the brainstem or PVN.

GLP-1 and control of meal size

A final issue is whether endogenously released GLP-1 works as a within-meal or across- meal stimulus for reducing food intake. The decreases in food intake that are typically elicited by GLP-1 (or Ex-4) are attributed to decreases in meal size, not meal number 48, 53, 56, 77. Ruttimann 56 and others have shown that GLP-1 works within a meal if administered during a first meal, and decreases meal size of that first meal without affecting intermeal interval or total food intake. In line with these results, Ex-4 decreased meal size across a 6h daily feeding period in non-human primates 77. Chelikani et al 48 reported that 3 h intrajugular infusions of GLP-1 reduced meal frequency in addition to meal size, but the reduction in meal size came before meal frequency. However, they further demonstrated that feeding remained reduced following the termination of the GLP-1 infusion, suggesting lasting effects on subsequent meals. Thus, examinations of the role for endogenous GLP-1 in the controls of meal size have produced mixed results. This may have to do with the timing of antagonist administration relative to the initiation of food intake.

The release and effects of GLP-1 may involve within meal enteroenteric reflexes and across meal central signaling to mediate changes in appetite. The timing and levels of GLP-1 may signal the type of nutrients, amount of food and/or timing of ingestion and the body may receive this information based on which central or peripheral receptors are activated. Additional knowledge on the modes and mechanisms of action of GLP-1 induced reductions in food intake may contribute to the development of obesity treatments targeting GLP-1 signaling.

Concluding Remarks

We have concentrated on reviewing the actions of endogenous GLP-1 on appetite in an attempt to understand its normal physiological role. Certainly the GLP-1 analogues that escape degradation by DPP-IV are effective at decreasing appetite, but the high incidence of side-effects reported in patients taking these analogs raises concerns about their utility for treating obesity. The GLP-1 analogues appear to activate additional mechanisms that are not utilized by endogenous GLP-1. GLP-1 and the synthetic analogues share a similar mode and binding affinity to the human GLP-1R, thus, it seems likely that the side effects are caused by greater GLP-1R stimulation from the long-lasting GLP-1 analogues 78. Understanding which GLP-1R populations are stimulated under endogenous GLP-1-induced decreases in appetite may help in designing effective obesity drugs without the negative side effects.

Acknowledgements

The drawing is courtesy of Alexander A. Moghadam.

Glossary

- Colonic transit

the time it takes a substance to enter the colon and move completely through the colon to be excreted.

- Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV)

an enzyme that degrades incretins such as GLP-1 and thus plays a major role in glucose metabolism. A new class of oral hypoglycemics called dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors work by inhibiting the action of this enzyme, thereby prolonging incretin effect in vivo.

- Exenatide

a GLP-1 like agonist used for the treatment of T2DM. It belongs to the group of incretin mimetics. Exenatide enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion by pancreatic beta- cells, suppresses glucagon secretion, and slows gastric emptying.

- Exendin-4 (Ex-4)

a hormone found in the saliva of the venomous lizard Gila monster. Ex-4, similar to GLP-1, regulates glucose metabolism and insulin secretion.

- Evoked activity

brain activity that is the result of a task, sensory input or motor output. It is the opposite of spontaneous brain activity that takes place in the absence of any explicit task.

- Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)

a gut hormone secreted from intestinal L cell. It is derived from selective cleavage of the proglucagon gene. The biologically active forms of GLP-1 are GLP-1-(7-37) and GLP-1-(7-36)amide.

- Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R)

G-protein-coupled receptor that binds specifically GLP1. GLP1R is expressed in pancreatic beta cells and in the brain where it is involved in the control of appetite. Activated GLP1R stimulates adenylyl cyclase resulting in increased insulin synthesis and release. Therefore, GLP1R has been suggested as a potential target for the treatment of diabetes.

- Ileal brake

the primary inhibitory feedback mechanism to control transit of a meal through the gastrointestinal tract. It helps optimize nutrient digestion and absorption.

- Incretins

a group of gastrointestinal hormones. They increase insulin release from pancreatic beta cells after eating, even before blood glucose levels rise. They also inhibit glucagon release from pancreatic alpha cells. Incretins slow the rate of absorption of nutrients into the blood stream by reducing gastric emptying and may directly reduce food intake.

- Liraglutide

a long-acting GLP-1 like agonist and anti-diabetic medication.

- Peristalsis

is a radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles, which propagates in a wave down the muscular tube, in an anterograde fashion. In humans, peristalsis is found in the contraction of smooth muscles to propel contents through the digestive tract.

- Secretagogue

a substance that causes another substance to be secreted.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mojsov S, et al. Preproglucagon gene expression in pancreas and intestine diversifies at the level of post-translational processing. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11880–11889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orskov C, et al. Tissue and plasma concentrations of amidated and glycine-extended glucagon-like peptide I in humans. Diabetes. 1994;43:535–539. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edholm T, et al. Differential incretin effects of GIP and GLP-1 on gastric emptying, appetite, and insulin-glucose homeostasis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 22:1191–1200. e1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre RS, et al. The neuroprotective effects of GLP-1: Possible treatments for cognitive deficits in individuals with mood disorders. Behav Brain Res. 237C:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drucker DJ, Rosen CF. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, obesity and psoriasis: diabetes meets dermatology. Diabetologia. 54:2741–2744. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2297-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vahl TP, et al. Meal-anticipatory glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in rats. Endocrinology. 151:569–575. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dailey MJ, et al. Disassociation between preprandial gut peptide release and food-anticipatory activity. Endocrinology. 153:132–142. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rask E, et al. Impaired incretin response after a mixed meal is associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic men. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1640–1645. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberge JN, Brubaker PL. Regulation of intestinal proglucagon-derived peptide secretion by glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide in a novel enteroendocrine loop. Endocrinology. 1993;133:233–240. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.1.8319572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reimer RA, et al. A human cellular model for studying the regulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4522–4528. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocca AS, Brubaker PL. Role of the vagus nerve in mediating proximal nutrient- induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1687–1694. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen PJ, et al. Distribution of glucagon-like peptide-1 and other preproglucagon- derived peptides in the rat hypothalamus and brainstem. Neuroscience. 1997;77:257–270. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grill HJ, et al. Attenuation of lipopolysaccharide anorexia by antagonism of caudal brain stem but not forebrain GLP-1-R. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1190–R1193. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00163.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinaman L. Interoceptive stress activates glucagon-like peptide-1 neurons that project to the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R582–R590. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.2.R582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinaman L. A functional role for central glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors in lithium chloride-induced anorexia. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1537–R1540. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.5.R1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao S, et al. Hindbrain leptin and glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor signaling interact to suppress food intake in an additive manner. Int J Obes (Lond) doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinaman L, Rothe EE. GLP-1 receptor signaling contributes to anorexigenic effect of centrally administered oxytocin in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R99–R106. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu I, et al. Identification and localization of glucagon-like peptide-1 and its receptor in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1987;121:1076–1082. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-3-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanse SM, et al. Identification and characterization of glucagon-like peptide-1 7-36 amide-binding sites in the rat brain and lung. FEBS Lett. 1988;241:209–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vahl TP, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptors expressed on nerve terminals in the portal vein mediate the effects of endogenous GLP-1 on glucose tolerance in rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4965–4973. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bullock BP, et al. Tissue distribution of messenger ribonucleic acid encoding the rat glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2968–2978. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa A, et al. Receptor gene expression of glucagon-like peptide-1, but not glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, in rat nodose ganglion cells. Auton Neurosci. 2004;110:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merchenthaler I, et al. Distribution of pre-pro-glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor messenger RNAs in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403:261–280. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990111)403:2<261::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Alessio D, et al. Fasting and postprandial concentrations of GLP-1 in intestinal lymph and portal plasma: evidence for selective release of GLP-1 in the lymph system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R2163–R2169. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00911.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen L, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36)amide is transformed to glucagon-like peptide-1-(9-36)amide by dipeptidyl peptidase IV in the capillaries supplying the L cells of the porcine intestine. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5356–5363. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kieffer TJ, et al. Degradation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and truncated glucagon-like peptide 1 in vitro and in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3585–3596. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holst JJ, Deacon CF. Glucagon-like peptide-1 mediates the therapeutic actions of DPP-IV inhibitors. Diabetologia. 2005;48:612–615. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1705-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amato A, et al. Peripheral motor action of glucagon-like peptide-1 through enteric neuronal receptors. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 22:664–e203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turcot V, et al. DPP4 gene DNA methylation in the omentum is associated with its gene expression and plasma lipid profile in severe obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19:388–395. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyazaki M, et al. Increased hepatic expression of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with insulin resistance and glucose metabolism. Mol Med Report. 5:729–733. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran GW, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 expression is reduced in Crohn's disease. Regul Pept. 177:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orskov C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide I receptors in the subfornical organ and the area postrema are accessible to circulating glucagon-like peptide I. Diabetes. 1996;45:832–835. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.6.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kastin AJ, et al. Interactions of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) with the blood-brain barrier. J Mol Neurosci. 2002;18:7–14. doi: 10.1385/JMN:18:1-2:07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schirra J, et al. Endogenous glucagon-like peptide 1 controls endocrine pancreatic secretion and antro-pyloro-duodenal motility in humans. Gut. 2006;55:243–251. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.059741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellstrom PM, et al. GLP-1 suppresses gastrointestinal motility and inhibits the migrating motor complex in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:649–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoder SM, et al. Stimulation of incretin secretion by dietary lipid: is it dose dependent? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G299–G305. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90601.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imeryuz N, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits gastric emptying via vagal afferent- mediated central mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G920–G927. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wettergren A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits gastropancreatic function by inhibiting central parasympathetic outflow. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G984–G992. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.5.G984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daniel EE, et al. Local, exendin-(9-39)-insensitive, site of action of GLP-1 in canine ileum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G595–G602. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00110.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tolessa T, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 retards gastric emptying and small bowel transit in the rat: effect mediated through central or enteric nervous mechanisms. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2284–2290. doi: 10.1023/a:1026678925120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wettergren A, et al. The inhibitory effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) 7-36 amide on gastric acid secretion in humans depends on an intact vagal innervation. Gut. 1997;40:597–601. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gulpinar MA, et al. Glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) is involved in the central modulation of fecal output in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G924–G929. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.6.G924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayachi SE, et al. Contraction induced by glicentin on smooth muscle cells from the human colon is abolished by exendin (9-39) Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:302–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakade Y, et al. Glucagon like peptide-1 accelerates colonic transit via central CRF and peripheral vagal pathways in conscious rats. Auton Neurosci. 2007;131:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Law NM, et al. Cholinergic stimulation enhances colonic motor activity, transit, and sensation in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1228–G1237. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams DL, et al. Leptin regulation of the anorexic response to glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor stimulation. Diabetes. 2006;55:3387–3393. doi: 10.2337/db06-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClean PL, et al. The diabetes drug liraglutide prevents degenerative processes in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 31:6587–6594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0529-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chelikani PK, et al. Intravenous infusion of glucagon-like peptide-1 potently inhibits food intake, sham feeding, and gastric emptying in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1695–R1706. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00870.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larsen PJ, et al. Systemic administration of the long-acting GLP-1 derivative NN2211 induces lasting and reversible weight loss in both normal and obese rats. Diabetes. 2001;50:2530–2539. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turton MD, et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 1996;379:69–72. doi: 10.1038/379069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang-Christensen M, et al. Central administration of GLP-1-(7-36) amide inhibits food and water intake in rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R848–R856. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V. Entry of exendin-4 into brain is rapid but may be limited at high doses. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:313–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams DL, et al. Evidence that intestinal glucagon-like peptide-1 plays a physiological role in satiety. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1680–1687. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbott CR, et al. The inhibitory effects of peripheral administration of peptide YY(3-36) and glucagon-like peptide-1 on food intake are attenuated by ablation of the vagal-brainstem- hypothalamic pathway. Brain Res. 2005;1044:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Talsania T, et al. Peripheral exendin-4 and peptide YY(3-36) synergistically reduce food intake through different mechanisms in mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3748–3756. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruttimann EB, et al. Intrameal hepatic portal and intraperitoneal infusions of glucagon- like peptide-1 reduce spontaneous meal size in the rat via different mechanisms. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1174–1181. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J, Ritter RC. Circulating GLP-1 and CCK-8 reduce food intake by capsaicin- insensitive, nonvagal mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 302:R264–R273. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00114.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baggio LL, et al. Oxyntomodulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 differentially regulate murine food intake and energy expenditure. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:546–558. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strubbe JWP, van Dijk G. Involvement of central GLP-1 circuitry in gastrointestinal motility. In. European Winter Conference on Brain Research. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hayes MR, et al. Caudal brainstem processing is sufficient for behavioral, sympathetic, and parasympathetic responses driven by peripheral and hindbrain glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor stimulation. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4059–4068. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayes MR, et al. Endogenous leptin signaling in the caudal nucleus tractus solitarius and area postrema is required for energy balance regulation. Cell Metab. 11:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barrera JG, et al. Hyperphagia and increased fat accumulation in two models of chronic CNS glucagon-like peptide-1 loss of function. J Neurosci. 31:3904–3913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2212-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sandoval DA, et al. Arcuate glucagon-like peptide 1 receptors regulate glucose homeostasis but not food intake. Diabetes. 2008;57:2046–2054. doi: 10.2337/db07-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Larsen PJ, et al. Central administration of glucagon-like peptide-1 activates hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons in the rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4445–4455. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seo S, et al. Acute effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on hypothalamic neuropeptide and AMP activated kinase expression in fasted rats. Endocr J. 2008;55:867–874. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang H. The school of human ecology. Louisiana State University; 2009. The role of glucagon-like peptide-1 on food intake, glucokinase expression and fatty acid metabolism. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bugarith K, et al. Basomedial hypothalamic injections of neuropeptide Y conjugated to saporin selectively disrupt hypothalamic controls of food intake. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1179–1191. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blevins JE, Baskin DG. Hypothalamic-brainstem circuits controlling eating. Forum Nutr. 63:133–140. doi: 10.1159/000264401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kinzig KP, et al. CNS glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors mediate endocrine and anxiety responses to interoceptive and psychogenic stressors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6163–6170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06163.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarkar S, et al. Glucagon like peptide-1 (7-36) amide (GLP-1) nerve terminals densely innervate corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res. 2003;985:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Uehara A, et al. Anorexia induced by interleukin 1: involvement of corticotropin- releasing factor. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R613–R617. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.3.R613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alhadeff AL, et al. GLP-1 neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract project directly to the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens to control for food intake. Endocrinology. 153:647–658. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dossat AM, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptors in nucleus accumbens affect food intake. J Neurosci. 31:14453–14457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3262-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiele TE, et al. Central infusion of GLP-1, but not leptin, produces conditioned taste aversions in rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R726–R730. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kinzig KP, et al. The diverse roles of specific GLP-1 receptors in the control of food intake and the response to visceral illness. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10470–10476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10470.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McMahon LR, Wellman PJ. Decreased intake of a liquid diet in nonfood-deprived rats following intra-PVN injections of GLP-1 (7-36) amide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:673–677. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scott KA, Moran TH. The GLP-1 agonist exendin-4 reduces food intake in nonhuman primates through changes in meal size. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R983–R987. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00323.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morioka T, et al. Enhanced GLP-1- and sulfonylurea-induced insulin secretion in islets lacking leptin signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 26:967–976. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mann RJ, et al. The major determinant of exendin-4/glucagon-like peptide 1 differential affinity at the rat glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor N-terminal domain is a hydrogen bond from SER-32 of exendin-4. Br J Pharmacol. 160:1973–1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]