Inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) of the liver are uncommon benign lesions of unclear etiology and behavior that were first described in 1953 by Pack and Baker.1,2 Histologically, these lesions are composed of inflammatory cells, histiocytes, and fibroblasts, and IPTs have been described in the literature as plasma cell granulomas, xanthogranulomas, histiocytomas, myofibrohistiocytic proliferations, or inflammatory myofibroblastic lesions. In addition to the liver, IPTs may develop in diverse extrahepatic locations such as the lungs, central nervous system, major salivary glands, larynx, bladder, breasts, pancreas, spleen, lymph nodes, skin, and soft tissues.3–12 Although uncommon, IPTs of the liver have been increasingly recognized in recent years, mainly in Asian countries. These lesions are often treated via hepatic resection because they are mistaken for malignant lesions.1,2

Case Report

A 40-year-old white Portuguese man with no significant medical history presented with a 4-week history of asthenia, malaise, headache, sore throat, vague upper abdominal discomfort, and intermittent fever. The patient also reported a weight loss of less than 10% of his body weight. The patient had not travelled outside of Europe but had been to France on a vacation approximately 1 month prior to symptom onset. He reported a recent change in his alimentary pattern, with heavy daily consumption of a variety of French cheeses that he had brought from France and continued to consume upon his return to Portugal. Empiric treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics had been attempted, with no clinical improvement. A physical examination did not reveal any stigmata of chronic liver disease or hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests revealed an aspartate aminotransferase level of 73 IU/L (normal, 10-37 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase level of 212 IU/L (normal, 10-37 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level of 550 IU/L (normal, 34-104 IU/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level of 922 IU/L (normal, 10-55 IU/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 72 (normal, 1-7), and cancer antigen (CA) 19.9 level of 45 ng/mL (normal, <37 ng/mL). In addition, the patient had negative serologic results for hepatotropic viruses, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and HIV 1 and 2.

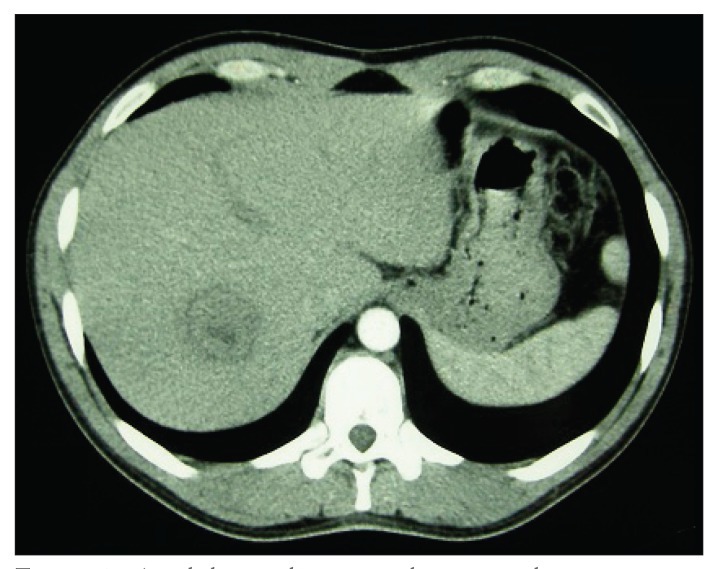

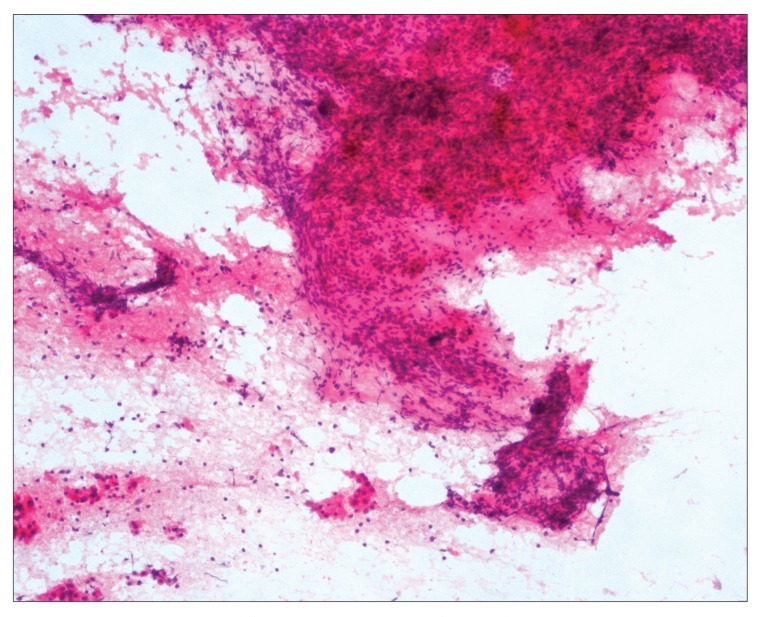

An abdominal ultrasound (US) of the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe revealed a heterogeneous, solid, mainly hypoechoic mass measuring 54 mm χ 50 mm and presenting with intrinsic vascularization on Doppler study. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a hypodense lesion measuring 41 mm χ 36 mm in liver segments VII/VIII, with a hypodense peripheral halo and no significant enhancement after endovenous iodine contrast (Figures 1). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed 1 week later revealed a well-circumscribed nodular lesion measuring 32 mm χ 31 mm in the segment VII/VIII transition; findings included the nonspecific features of a hypointense T1 central area and a hyperintense T2 central area with no contrast uptake, a hypointense peripheral halo in T1-weighted and T2-weighted images with progressive contrast uptake, and no washout on the dynamic study. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the lesion revealed a polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate with macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasmocytes in a prominent myxoid collagen stroma, with no atypical hepatocytes and rare bile ducts; these findings were suggestive of an IPT (Figures 2).

Figure 1.

An abdominal computed tomography scan showing a hypodense lesion measuring 41 mm x 36 mm in liver segments VII/VIII, with a hypodense peripheral halo and no significant contrast enhancement.

Figure 2.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology showing a polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate in myxoid collagen stroma, with no atypical hepatocytes and rare bile ducts, compatible with an inflammatory pseudotumor (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 100χ magnification).

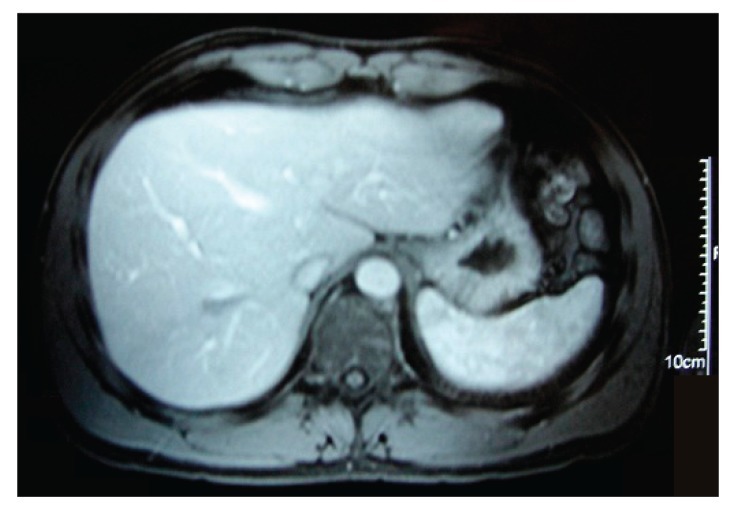

Follow-up via clinical, analytic, and radiologic surveillance was adopted, and no empiric treatment was initiated. The patient became asymptomatic approximately 6 weeks after symptom onset. Laboratory test results 2 months after the patient’s initial presentation showed significant improvement. An abdominal US performed 1 month later revealed a normal homogeneous hepatic parenchyma with no residual lesions. An MRI scan performed within 3 months revealed a small nodular area measuring 20 mm χ 15 mm that was hypointense in both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images without contrast uptake; this finding was interpreted to be residual fibrosis in the location of the IPT (Figures 3). Findings from subsequent US abdominal imaging (performed at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years) were entirely normal. Laboratory test results at the same time points were also normal.

Figure 3.

An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging scan at 3 months showing a small area of residual fibrosis that was hypointense in both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images without contrast uptake.

Discussion

The majority of hepatic IPTs occur in childhood and early adulthood.2 In adults, the male-to-female ratio ranges from 1:1 to 3.5:1.2 IPTs of the liver appear to be more common in non-European populations.13 Our patient was a white Portuguese man who had no significant medical history, no history of travelling outside of Europe, and who lived in good environmental salubrity conditions. As with our patient, most liver IPTs that have been reported in the literature have been solitary solid tumors, mainly arising in the right hepatic lobe.2

The etiology and pathogenesis of hepatic IPTs remain unknown, although they are thought to involve a reactive inflammatory process. Etiologic causes that have been hypothesized include infections, trauma, vascular causes, and autoimmune disorders.14 Most reported cases of hepatic IPTs have a possible antecedent cause, such as travel to the tropics, biliary disease, gastrointestinal infection, or ulcerating gastric carcinoma.1 IPTs of the liver could represent an atypical or exaggerated response to microorganisms entering the liver through the portal circulation. However, no evidence of infectious organisms has been demonstrated in most of the reported case series. Nevertheless, some cases have reportedly involved EBV-positive tumors, and other liver IPTs have contained parasitic fragments or microorganisms such as Gram-positive cocci, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Escherichia coli.15 These observations suggest that an infectious agent may be involved in the development of IPTs of the liver, although no single organism has been consistently implicated. We could speculate whether our patient’s IPT was triggered by his recent ingestion of large amounts of cheese that had been kept under suboptimal storage conditions for several weeks; however, no common symptoms of gastrointestinal infection (such as vomiting or diarrhea) were observed, and a direct cause-effect relationship could not be firmly established.

Biologically, no specific laboratory markers are useful for diagnosing IPTs. As was seen in our patient, a high serum CA 19-9 level has been reported with IPTs.16 Serum analyses are usually normal or may reveal an acute-phase response with an elevated ESR and/or white blood cell count. Liver function tests may reveal elevated ALP and GGT levels; bilirubin levels are usually not elevated unless the patient has preexisting liver disease.15

The imaging features of liver IPTs have not been discussed much in the literature. On CT scans, these lesions may appear to be well-circumscribed or poorly marginated heterogeneous lesions. Yoon and associates summarized CT findings suggestive of IPTs of the liver.17 Most importantly, the enhancement pattern of a hepatocellular carcinoma differs from that of an IPT, as the former pattern is hyperdense in the arterial phase and hypodense with capsule enhancement on a delayed-phase CT scan; in addition, the latter pattern has nonspecific features and (as with our patient) usually shows a hypoattenuating mass and a hypodense peripheral halo with no significant enhancement after endovenous contrast.

Tissue sampling is required for establishing the diagnosis of IPT. The histologic appearance of IPTs may be highly variable. Generally, there is a benign spindle-cell proliferation in a myxoid collagen stroma with an inflammatory component of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes.2 Ideally, the diagnosis of IPT should be made via a core biopsy. Nevertheless, as with our patient, FNA of the lesion can support the diagnosis of an IPT. However, when the lesion is highly fibrotic, FNA samples can be difficult to obtain and can lead to misdiagnosis.15

The natural history of liver IPTs is not often discussed in the literature because initial misdiagnoses and local complications often lead to surgical resection. However, as with our patient, spontaneous and complete regression of hepatic IPTs has been reported for intrahepatic tumors of the right lobe. In these cases, the average time between diagnosis and spontaneous regression was 4 months.2 IPTs of the liver are often misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinomas, cholangiocarcinomas, secondary tumors, or abscesses because of their nonspecific clinical, radiologic, and biochemical presentations. Thus, management of IPTs ranges from conservative treatment to hepatic resection or even liver transplantation.1,2 Conservative treatment has included antibiotics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; if the patient has biliary obstruction, biliary stents may be placed.18–20

Differentiating IPTs from malignant liver tumors has been assuming greater importance because hepatic surgery is being performed more frequently, due to its increased safety and the adoption of a more aggressive treatment approach via resection of liver masses. Thus, some doctors have advocated the use of hepatic resection for IPTs of the liver, taking into account the possible destructive nature of the lesions and the uncertainty of their potential for malignancy. However, immunohistochemical analysis has shown that IPTs are benign lesions with no evidence of malignant transformation. Moreover, a number of reports published in the literature suggest that the natural history of these lesions leads to complete resolution.15 These observations provide good evidence that progressive IPTs of the liver are exceedingly rare and typically resolve without treatment. Complete and sustained resolution was observed in our patient at 36 months.

In conclusion, if an atypical solid mass is found in the liver, IPT should be considered as a diagnosis, particularly if the mass is accompanied by a clinical inflammatory process. In addition, liver needle biopsy should be performed to prevent unnecessary surgery. Conservative management is appropriate if the diagnosis is confirmed via the biopsy specimen and the patient is followed with clinical examinations and imaging until resolution of the lesion.

References

- 1.Pack GT, Baker HW . Total right hepatic lobectomy; report of a case. Ann Surg. 1953;138:253–258. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195308000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lévy S, Sauvanet A, Diebold MD, Marcus C, Da Costa N, Thiefin G. Spontaneous regression of an inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver presenting as an obstructing malignant biliary tumor. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:371–374. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(01)70422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahale A, Venugopal A, Acharya V, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung (pseudotumor of the lung) Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2006;16:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sitton JE, Harkin JC, Gerber MA. Intracranial inflammatory pseudotumor. Clin Neuropathol. 1992;11:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams SB, Foss RD, Ellis GL. Inflammatory pseudotumours of the major salivary glands. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:896–902. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albizzati C, Ramesar KC, Davis BC. Plasma cell granuloma of the larynx (case report and review of the literature) JLaryngol Otol. 1988;102:187–189. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100104487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrick DD, Kabalin JN, Daniels GF, Jr, Epstein AB, Fielding IM. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the bladder. J Urol. 1992;148:141–144. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettinato G, Manivel JC, Insabato L, De Chiara A, Petrella G. Plasma cell granu-loma (inflammatory pseudotumor) of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;90:627–632. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/90.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palazzo JP, Chang CD. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the pancreas. Histopa-thology. 1993;23:475–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu KH, Liu HW, Leung CY. Inflammatory pseudotumours of the spleen. Histopathology. 1990;16:302–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrone T, De Wolf-Peeters C, Frizzera G. Inflammatory pseudotumor of lymph nodes. A distinctive pattern of nodal reaction. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:351–361. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198805000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurt MA, Santa Cruz DJ. Cutaneous inflammatory pseudotumor. Lesions resembling “inflammatory pseudotumors” or “plasma cell granulomas” of extracu-taneous sites. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:764–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid A, Janig D, Bohuszlavizki A, Henne-Bruns D. Inflammatory pseudo-tumor of the liver presenting as incidentaloma: report of a case and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1009–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsou YK, Lin CJ, Liu NJ, Lin CC, Lin CH, Lin SM. Inflammatory pseu-dotumor of the liver: report of eight cases, including three unusual cases, and a literature review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:2143–2147. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koea JB, Broadhurst GW, Rodgers MS, McCall JL. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: demographics, diagnosis, and the case for nonoperative management. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:226–235. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa T, Yokoi H, Kawarada Y. A case of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver causing elevated serum CA 19-9 levels. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2551–2555. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon KH, Ha HK, Lee JS, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: CT histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1999;211:373–379. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma36373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jai’s P, Berger JF, Vissuzaine C, et al. Regression of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver under conservative therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:752–756. doi: 10.1007/BF02064975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakozaki Y, Katou M, Nakagawa K, Shirahama T, Matsumoto T. Improvement of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver after nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1121–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pokorny CS, Painter DM, Waugh RC, McCaughan GW, Gallagher ND, Tattersall MH. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver causing biliary obstruction. Treatment by biliary stenting with 5-year follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:338–341. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199106000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]