Abstract

Non-haemolytic transfusion reactions are the most common type of transfusion reaction and include transfusion-related acute lung injury, transfusion-associated circulatory overload, allergic reactions, febrile reactions, post-transfusion purpura and graft-versus- host disease. Although life-threatening anaphylaxis occurs rarely, allergic reactions occur most frequently. If possible, even mild transfusion reactions should be avoided because they add to patients' existing suffering. During the last decade, several new discoveries have been made in the field of allergic diseases and transfusion medicine. First, mast cells are not the only cells that are key players in allergic diseases, particularly in the murine immune system. Second, it has been suggested that immunologically active undigested or digested food allergens in a donor's blood may be transferred to a recipient who is allergic to these antigens, causing anaphylaxis. Third, washed platelets have been shown to be effective for preventing allergic transfusion reactions, although substantial numbers of platelets are lost during washing procedures, and platelet recovery after transfusion may not be equivalent to that with unwashed platelets. This review describes allergic transfusion reactions, including the above-mentioned points, and focusses on their incidence, pathogenesis, laboratory tests, prevention and treatment.

Keywords: allergic transfusion reaction, IgE, tryptase, basophil activation test, washed platelets

Incidence

Although reports revealed that allergic reactions with platelets (PLTs) and red blood cells (RBCs) have an incidence rate of 3·7% and 0·15%, respectively, a review of the literature showed that the incidence rate varied by more than 100-fold, probably because of differences in pre-medication use, patient characteristics, product manufacturing, storage time, reporting rates, reaction definitions and monitoring standards (Geiger & Howard, 2007). A Canadian group showed similar allergic reaction incidences with PLTs and RBCs and an allergic reaction incidence of 0·19% with plasma transfusions (Kleinman et al, 2003). Thus, transfusions with PLTs are apparently associated with a higher risk than those with other components, although it is unknown whether these differences are due to the nature of each component or patient factors, including background diseases and history of previous transfusions.

Allergen-dependent pathways

Plasma proteins as allergens

The allergens that cause allergic transfusion reactions are plasma proteins such as IgA (Vyas et al, 1968; Schmidt et al, 1969; Sandler et al, 1995) and haptoglobin (Hp) (Koda et al, 2000; Shimada et al, 2002). Although there are case reports of anaphylactic reactions, many of which were serious (Vyas et al, 1968; Schmidt et al, 1969; Sandler et al, 1995; Koda et al, 2000; Shimada et al, 2002), there are no reliable estimates regarding the incidence of IgA- and Hp-mediated allergic transfusion reactions. The number of patients who have IgA- or Hp-deficiency and specific antibodies but are never diagnosed because of the absence of symptoms after transfusion remains unknown. Therefore, at least with regard to IgA deficiency, reactions usually do not occur and anaphylaxis appears to be relatively rare (Sandler, 2006).

Although most IgA-related anaphylactic reactions occur in those who are IgA-deficient (serum IgA <0·5 mg/l) and in whom there are detectable serum class-specific IgA antibodies, there are patients with normal serum concentrations of IgA and subclass (IgA1 or IgA2)- or allotype [IgA2m(1) or IgA2m(2)]-specific IgA antibodies who have experienced severe acute reactions to blood transfusions (Sandler et al, 1995).

Plasma Hp levels should be carefully measured because they are known to decrease to below detectable levels in certain pathological conditions, such as haemolysis and liver dysfunction (Rougemont et al, 1980). In these instances, a DNA diagnosis of Hp deficiency is useful (Koda et al, 2000).

Of note, evident racial differences in the incidence of IgA- and Hp-deficiency and consequent racial differences in the prevalence of anaphylactic shock mediated by these antibodies have been observed. The HPdel allele frequency in East and South-east Asian populations is 1·5–3%. Therefore, the incidence of its deficiency is 1/1 000 to 1/4 000. However, this allele has not been detected in African, Western and Southern Asian or European populations (Koda et al, 2000; Shimada et al, 2007; Soejima et al, 2007). In contrast, the incidence of IgA deficiency among the Japanese was reported to be approximately 1/30 000, which was lower than that reported among Europeans (1/2 500) (Ropars et al, 1982; Kanoh et al, 1986). Therefore, Hp-deficiency and Hp antibodies should be considered among Eastern Asians, while IgA deficiency and IgA antibodies should be considered among Europeans, respectively, as the cause of transfusion-related anaphylactic reactions.

Although rare, anaphylactic shock after transfusions has been reported in complement C4-deficient (Lambin et al, 1984; Westhoff et al, 1992) and von Willebrand factor-deficient (Bergamaschini et al, 1995) patients. Factor IX inhibitors in haemophilia B patients occasionally induce anaphylactic shock after Factor IX transfusions (Warrier & Lusher, 1998).

Chemical allergens

Besides plasma proteins, methylene blue, which is a reagent used for viral inactivation of fresh frozen plasma, has been reported to cause anaphylactic shock after plasma transfusion (Dewachter et al, 2011; Nubret et al, 2011). Although the risk appears to be extremely low in light of the widespread use of this blood component, precautions need to be taken in countries and regions that have a methylene blue inactivation system.

Food allergens

Recently, an intriguing case report suggested that transfusion-related anaphylaxis occurred after passive transfer of peanut allergens to a sensitized person (Jacobs et al, 2011). Briefly, a 6-year-old boy had an anaphylactic reaction with rash, angioedoema, hypotension and difficult breathing during a PLT transfusion. Laboratory tests ruled out possible deficiencies in IgA, Hp and C4; allergies to drugs or latex; the presence of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) antibodies and transfusion-associated acute lung injury (TRALI). However, the patient had a history of serious peanut allergy at the age of 1 year and his serum contained specific IgE antibodies against the major peanut allergen Ara h2, which is very resistant to digestion by pepsin. In addition, three of five blood donors recalled having eaten several handfuls of peanuts the evening before they donated blood. This circumstantial evidence suggested that an anaphylactic reaction occurred after the passive transfer of peanut allergens. This is consistent with the fact that substantial amounts of food antigens are absorbed into the blood circulation in a digested form but retain a certain molecular size and antigenicity (Untersmayr & Jensen-Jarolim, 2008). The direct way to prove this hypothesis would be to show these allergens in the transfused blood. However, no data demonstrating the presence of peanut allergens in the donors' blood were provided. The authors only referred to a previous report, which showed that a digestion-resistant peptide of Ara h2 was detected in the serum for up to 24 h after ingestion (Baumert et al, 2010). In addition, other investigators have unsuccessfully attempted to detect any circulating peanut proteins in volunteers after very large ingestions (Vickery et al, 2011). There is scepticism regarding the assumption that physiologically relevant contamination had occurred when only three of five donors had consumed several handfuls of peanuts the evening before they donated blood (Vickery et al, 2011). The true incidence of these reactions is obscure. Therefore, we need to assume a cautious attitude towards this issue until more concrete evidence is provided.

IgE-, FcεR-, mast cell- and histamine-mediated sub-pathway versus IgG-, FcγRs-, basophil- and platelet-activating factor (PAF)-mediated sub-pathway

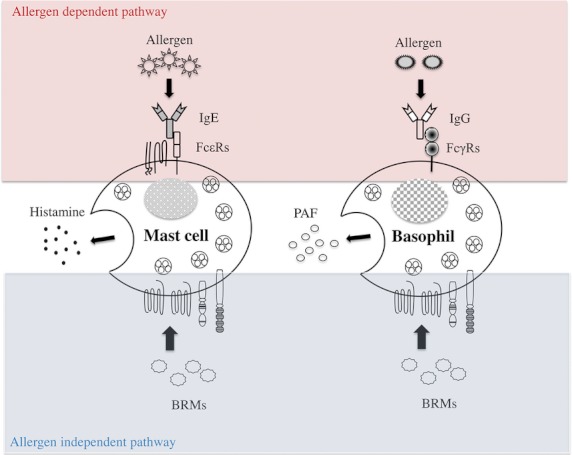

IgG antibodies are usually detected in both IgA- and Hp-mediated anaphylaxis, while IgE antibodies have also been detected in several studies (Burks et al, 1986; Harper et al, 1995; Dioun et al, 1998; Shimada et al, 2002). Therefore, both IgG- and IgE-mediated mechanisms are possible. In cases of anaphylaxis, it is important to examine for IgG antibodies and, if possible, the IgE class. Although IgE, FcεR, mast cells and histamine are considered to play major roles in anaphylaxis, IgG-mediated systemic anaphylaxis was recently demonstrated in the murine system involving FcγRs, basophils and PAF as major players (Fig 1). In this reaction, PAF rather than histamine was the major chemical mediator that induced systemic anaphylaxis (Tsujimura et al, 2008). Although it remains uncertain whether this pathway is present in humans, there is supportive evidence for this mechanism.

Fig. 1.

Allergen-dependent and -independent pathways and mast cell-mediated and basophil-mediated sub-pathways in the murine immune system. The allergen-dependent pathway is triggered when allergens bind to antibodies that are bound by FcRs expressed on mast cells and basophils. Subsequently, activated mast cells and basophils release chemical mediators. The allergen-independent pathway is triggered when biological response modifiers (BRMs) bind to their respective receptors expressed on mast cells and basophils, which results in the activation of these cells. In the allergen-dependent mast cell-mediated sub-pathway, IgE and FcεR come into play and histamine is released. In contrast, in the allergen-dependent basophil-mediated sub-pathway, IgG and FcγRs come into play and platelet-activating factor (PAF) is released. Neutrophils and monocytes are reported to be other key players in allergy. IgG and FcγRs are involved and PAF is released.

For example, allergen-specific IgG antibodies rather than IgE antibodies were detected in individuals who manifested systemic anaphylaxis against medical reagents, such as protamine, dextran and recombinant IgG, including anti-tumour necrosis factor-α (Kraft et al, 1982; Weiss et al, 1989; Adourian et al, 1993; Cheifetz et al, 2003). Vadas et al (2008) investigated the roles of PAF and PAF acetylhydrolase, the enzyme that inactivates PAF, in anaphylaxis in humans. They concluded that a failure of PAF acetylhydrolase to inactivate PAF may contribute to the severity of anaphylaxis on the basis of the following observations: (i) serum PAF levels were directly correlated with anaphylaxis severity, (ii) serum PAF acetylhydrolase activity was inversely correlated with anaphylaxis severity and (iii) PAF acetylhydrolase activity was significantly lower in patients who had fatal anaphylactic reactions to peanuts than in controls (Vadas et al, 2008).

In addition to basophils, neutrophils (Jönsson et al, 2011, 2012) and monocytes (Strait et al, 2002) have also been reported to play critical roles in the onset of anaphylaxis in the murine system. In these pathways, FcγRs, IgG and PAF are involved. However, the exact players, antibody class(es) and the chemical mediators in the human system remain to be determined. Nevertheless, extensive studies are needed before a final conclusion is reached on the IgG-, FcγRs- and PAF-mediated pathways in the human system.

Allergen-independent pathways

An alternative, putative mechanism underlying allergic transfusion reactions is that biological response modifiers (BRMs), such as inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, accumulate in blood components during storage, are infused along with transfused blood and result in allergic reactions (Fig 1). Stored PLT concentrate supernatants (PC-SNs) accumulate striking levels of BRMs during storage, including vascular endothelial growth factor, soluble CD40 ligand, histamine, transforming growth factor-β1 and RANTES (Wadhwa et al, 1996; Edvardsen et al, 1998; Phipps et al, 2001; Wakamoto et al, 2003; Garraud et al, 2012). There is reason to believe that these molecules are infused at what may be clinically significant doses and possibly alter a recipient's immune functions. Although the roles of these BRMs in the onset of allergic reactions remain largely unknown, it is possible that these or other substances induce or modulate allergic reactions.

Patient factors other than allergens and antibodies

It is known that sera from some patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria have detectable histamine-releasing activity (HRA). Based on this fact, Azuma et al (2009a) published a unique report on patient factors in allergic reactions. They noted HRA-like activity, which is the ability to induce Ca2+ influx into cultured mast cells (CaIA), in the pre-transfusion sera of patients with transfusion reactions. This suggested that CaIA may be attributed to adverse reactions, particularly urticaria-like manifestations (Azuma et al, 2009a). Because a calcium influx is known to precede histamine release from mast cells (Ozawa et al, 1993; Baba et al, 2008), they speculated that a serum sample showing CaIA activity could potentially induce histamine release, although in small amounts, and that mast cells may be pre-activated to a certain degree beforehand and tend to degranulate when an allergenic blood component is transfused.

This group also encountered another transfusion reaction case that suggested the presence of patient factors. This was a life-threatening reaction with hypotension that occurred after transfusion of fresh frozen plasma containing CD36 (Nak) isoantibodies (Morishita et al, 2005). These CD36 antibodies exhibited PLT-activating capability mediated though FcγRIIa, and, interestingly, PLTs from healthy human subjects exhibited a considerable degree of heterogeneity in their responsiveness to this plasma. The PLT surface expression levels of CD36 and FcγRIIa and their degree of binding to these antibodies were apparently associated with the profound differences in PLT responsiveness to this plasma (Wakamoto et al, 2005).

Passive transfer of antibodies and passive sensitization

Passive transfer of antibodies

In a study of IgA-deficiency among 73,569 blood donors, Vyas et al (1975) found 113 donors who were IgA-deficient. Of these, 13 had class-specific or high-titre IgA antibodies. However, no noticeable adverse reactions were observed (Vyas et al, 1975). In another study, Winters et al (2004) reviewed 22 apheresis PC transfusions derived from four IgA-deficient donors with IgA antibodies and observed no allergic reactions. Therefore, passive transfer of IgA antibodies may not elicit a transfusion reaction. To date, no reports on the effects of passive transfer of Hp antibodies have been published. Therefore, the risk of immediate-type allergic reactions elicited by passive transfusion of plasma protein antibodies appears to be very low.

Passive sensitization

When IgE antibodies against certain allergens, usually foods, inhalant allergens or drugs, are infused into a patient as part of a transfusion, the patient's mast cells and basophils will capture the infused IgE antibodies via the FcεRs expressed on these cells' surfaces. This is so-called passive sensitization. Allergic reactions can occur after a patient ingests or inhales these allergens. One study found that 23% of donors had significant levels of IgE antibodies to common allergens (Johansson et al, 2005a). Therefore, the risk of passive sensitization by blood and plasma transfusion is probably not low.

The same group of investigators subsequently performed an in vivo study in which two units (each approximately 300 ml) containing known concentrations of IgE antibodies to timothy grass pollen (8–205 kilo units antigen (kUA)/l) were selected and transfused into patients (Johansson et al, 2005b). IgE in the transfused plasma could be detected in the circulation of the recipients within 3 h after transfusion; the mean half-life of IgE was 1·13 d. Basophil sensitization was obvious in the 3 h sample, and it increased rapidly to a peak after 3·4 d and then declined over days to weeks. This indicated that IgE antibodies to certain allergens could sensitize patient basophils.

Actual cases of passive sensitization have also been reported. Branch and Gifford (1979) reported generalized urticaria in a recipient who received cephalothin 2 d after a whole blood transfusion from four donors. One of these donors was allergic to cephalothin and had developed antibodies against this antibiotic. Cephalothin antibodies were identified in the recipient's blood after the transfusion, but not before the transfusion.

Recently, a unique case of passive transfer of nut allergy after transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) was reported (Arnold et al, 2007). A non-atopic female patient received a transfusion of two FFP units. Two days later, she ate a muffin and some peanut butter and developed throat tightness, dyspnoea, dysphagia and a pruritic rash within minutes. One week later, a skin prick test for peanut protein was positive, and peanut-specific IgE levels were 2·7 kU/l (normal levels: <0·35 kU/l). Two months later, a second skin prick test was negative and peanut-specific IgE was undetectable. No reaction was observed following a supervised oral peanut challenge test 3 months after her transfusion. One of the FFP units was traced back to a whole blood donor with a history of peanut allergy and anaphylaxis. A subsequent peanut skin prick test for that donor was positive, and her peanut-specific IgE levels were >100 kU/l.

Laboratory tests

Plasma protein levels and plasma protein antibodies against IgA and Hp of both the IgG and IgE classes, if possible, need to be examined first. In-house systems are typically used to detect these deficiencies and antibodies, although commercial systems recently became available for detecting IgA deficiency and IgA antibodies (Palmer et al, 2012). Even without identifying the allergens and antibodies, it is possible to examine whether transfused blood products were causative and whether the reactions were allergic in nature on the basis of the following two tests.

Tryptase test

Tryptase is the most abundant secretory granule-derived serine proteinase contained in mast cells. Elevated tryptase levels in serum, plasma and other biological fluids are consistent with mast cell activation in systemic anaphylaxis and other immediate hypersensitivity allergic reactions (Schwartz et al, 1987, 1995). In the above-mentioned anaphylaxis case that occurred after passive transfer of peanut allergens to a sensitized boy, the serum tryptase levels after this reaction were significantly high and suggested a causative relationship between the reaction and the transfusion (Jacobs et al, 2011). In two of three recent anaphylactic reaction cases that occurred after transfusions of methylene blue-treated plasma, serum tryptase levels were elevated and aided in the diagnoses (Dewachter et al, 2011; Nubret et al, 2011). In Japan, serum tryptase levels are measured in patients suffering from non-haemolytic transfusion reactions if an allergic reaction is suspected and the patients' serum samples are available. It has been shown that the tryptase test is useful in diagnosing allergic transfusion reactions (Hirayama, 2010). However, it has a couple of drawbacks.

First, it is often difficult to obtain a patient's serum sample for a tryptase test because of the short tryptase half-life, which is only 2 h after its release into the circulation (Schwartz, 1990). Second, only a small amount of tryptase is produced by basophils, the other mediator of allergic reactions (Castells et al, 1987; Foster et al, 2002). In contrast, the basophil activation test (BAT) has no restrictions regarding the timing for patient sample collection and can assess basophil activation.

Basophil activation test (BAT)

The BAT was recently developed for managing allergic diseases. In this test, a patient's whole blood sample is incubated with an allergen. Subsequent basophil activation is assessed using flow cytometry on the basis of upregulation of cell degranulation/activation markers, CD63 or CD203c (Bühring et al, 1999; Boumiza et al, 2005). This test was recently applied to transfusion medicine. In the three above-mentioned anaphylactic reaction cases that occurred after methylene blue-treated plasma transfusion, the BAT was positive (Dewachter et al, 2011; Nubret et al, 2011). All three patients showed a positive reaction to methylene blue and/or patent blue, a methylene blue-related dye that is more antigenic than methylene blue. One patient was also BAT-positive for transfused FFP.

We assessed whether the BAT could be applied to transfusion medicine using PC-SNs from nine cases with allergic transfusion reactions and 12 cases without transfusion reactions (Matsuyama et al, 2009). Basophils were obtained from whole blood samples of healthy subjects because the patients' blood was not available. Three of 9 PC-SNs with allergic reactions activated basophils in at least one of five blood samples. The degree of basophil activation was quite different among the blood panels, suggesting the involvement of patient factors in the onset of allergic reactions. In contrast, only one of 12 PC-SNs without allergic reactions elicited basophil activation; this was probably a false BAT-positive result because that PC-SN was BAT-positive only to one of the five blood samples. Furthermore, the extent of CD203c up-regulation was minimal and close to the cut-off point. These data suggest that the BAT may be a useful tool for examining allergic transfusion reactions.

Allergic transfusion reactions are usually diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and their time of onset (immediate or after transfusion). Tests for plasma protein deficiency and antibodies are not always performed. Even if these tests are performed, they are usually negative. Therefore, in many allergic reaction cases, there is no evidence other than that the reactions were truly allergic in nature and the transfusion was causative. If a BAT is performed using residual transfused blood and the patient's blood is positive, it may be possible to conclude that the transfused blood elicited the reaction. Unfortunately, the BAT has only just begun to be used in transfusion medicine. Therefore, its usefulness has not yet been fully evaluated. In addition, its sensitivity and specificity remain to be determined (Hirayama, 2010). Therefore, similar but larger-scale studies are required to make a final evaluation of the BAT.

Prevention

Pre-transfusion medications

Acetaminophen, a representative antipyretic, and diphenhydramine, a well-known anti-histaminic, are widely used as pre-transfusion medications to prevent transfusion reactions, despite the lack of evidence regarding their preventative effects.

Kennedy et al (2008) conducted a large, prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of acetaminophen and diphenhydramine as pre-transfusion medications for preventing transfusion reactions versus a placebo and focused on the two major reaction types: febrile and allergic. Study medications were administered 30 min before the transfusions. Patients were monitored for reaction symptoms that developed within 4 h of the transfusion. A total of 315 eligible haematology/oncology patients were enrolled. Of these, 62 developed transfusion reactions while receiving a total of 4199 transfusions. Twenty-nine reactions occurred in patients who received the active drug and who had received a total of 2008 transfusions (1·44/100 transfusions), while 33 reactions occurred in patients who received the placebo and who had received a total of 2191 transfusions (1·51/100 transfusions). The majority of these reactions (36/62) were urticarial in nature and occurred at the same rate between the active drug and placebo groups. However, there was a limitation to this study; it was unknown whether diphenhydramine was useful for preventing recurrent reactions because patients with a history of allergic reactions were excluded.

Sanders et al (2005) performed a retrospective study of 7900 transfusions administered to 385 paediatric patients with cancer or who required haematopoietic stem cell transplantations. The incidence of allergic reactions was 0·75%. Allergic reactions were associated with 0·9% transfusions in patients who were administered diphenhydramine compared with 0·56% in those patients who were not administered this drug.

These two reports marginally support the common practice of pre-transfusion medication, particularly for chronically transfused patients. One drawback is that diphenhydramine may not be sufficiently strong to prevent allergic reactions. However, this assumption remains unconfirmed because the effects of stronger pre-medications, such as steroids, remain unknown.

Plasma-reduced (or concentrated) PLTs and washed PLTs

Although it remains unknown whether allergic reactions after PLT transfusions are caused by plasma proteins and their associated antibodies or BRMs, it has been noted that decreased amounts of plasma decreases the risk of allergic reactions. Decreasing the amount of plasma in PLT preparations can be achieved in three ways. One is to use PLTs from several buffy coats, which are pooled and supplemented with a solution other than plasma. This decreases the residual plasma content to 30–40% of the total volume (plasma-reduced PLTs). The second approach is to use apheresis PLTs in which highly concentrated PLTs are prepared using an apheresis device such as Trima Accel (Daskalakis et al, 2012; Johnson et al, 2012) or Amicus (Vassallo et al, 2010) with (plasma-reduced PLTs) or without (concentrated PLTs) adding a supplemental solution. The third approach is to use both pooled and apheresis PLTs. As much plasma as possible is removed using centrifugation or a cell processor, such as the Cobe 2991, after which PLTs are re-suspended in a supplemental solution (washed PLTs).

Using these methods, the residual plasma amounts with washed PLTs are usually <10%. Five studies evaluated plasma-reduced PLTs, concentrated PLTs and washed PLTs for their preventative effects against allergic transfusion reactions. These results are summarized in Table I. The conclusions drawn from these studies are as follows:

Table I.

Summary of studies investigating the effectiveness of plasma-reduced and washed PLT transfusion

| Findings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study type | Pooled or apheresis | Plasma-reduced or washed | Residual plasma content | Additional Solution | Patients (n) | Cases/allergic reactions per transfusion (n) | Transfusion reactions | Timing of transfusion after preparation | Other observations |

| de Wildt-Eggen et al (2000) | Randomized | Pooled | Plasma-reduced | Approximately 30% | PAS-II | 21 | Control: 5/192 plasma-reduced: 0/132 | Total reactions: 23/192 (12%) in control vs. 7/132 (5·3%) in plasma-reduced group, P < 0·05; allergic: 5/192 in control vs. 0/132 in plasma-reduced group, P < 0·05. | Up to 4 d. but no information about how long preventive effects last after preparation. | PLT count recovery: no information |

| 1-h and 20-h CCI after plasma-reduced PLT transfusion were slightly, but significantly lower than CCI after control PLT transfusion. | ||||||||||

| Tobian et al (2011) | Observational | Apheresis | Plasma-reduced (concentrated) | Less than 33% | None | 91 | Control: 160/3 193 concentrated: 23/3 326 | Concentrated PLTs reduced allergic reactions in 91 of 135 patients (67%) who had developed significant or multiple allergic reactions. 160/3 193 (5·0%) in control vs 23/3 326 (0·7%) in concentrated, P < 0·001. | No information | PLT count recovery and CCI: see Karafin et al (2012) below |

| Washed RBCs also significantly reduced allergic reactions to RBCs. | ||||||||||

| Washed by Cobe 2 991 | No information | Saline | 44 | Control: 89/1 413 concentrated: 50/1 001 washed: 12/2 857 | Concentrated PLTs failed to reduce allergic reactions in 44 of 135 patients (33%) who had developed significant or multiple allergic reactions. 89/1 413 (6·3%) in control vs 50/1 001 (5·0%) in concentrated, P = 0·176. Transfusion with washed PLTs significantly reduced allergic reactions [12/2 857 (0·4%), P < 0·001]. | |||||

| 44 | Control: 57/969 washed: 9/1 225 | Washed PLTs reduced allergic reactions in 44 patients who had developed severe or life-threatening allergic reactions. | ||||||||

| 57/969 (5·9%) in control vs 9/1 225 (0·7%) in washed, P < 0·001 | ||||||||||

| Karafin et al (2012) | Observational | Plasma-reduced (concentrated) | Less than 33% | None | PLT count recovery: 79% (P < 0·001). | |||||

| 0-1-h CCI was comparable, but 20-h CCI was reduced by 25% (P < 0·03). | ||||||||||

| Washed by Cobe 2991 | No information | Saline | PLT recovery: 80% (P < 0·001). | |||||||

| 1-h and 20-h CCI were reduced by 21% and 41%, respectively (P < 0·001) | ||||||||||

| Silvergleid et al (1977) | Observational | Pooled | Washed by centrifugation | Less than 1% | Hand-made solution* | 6 | Incidence is not clearly described | Massive ulticaria, extensive ulticaria, and severe serum sickness were prevented. | Immediately | PLT count recovery: more than 90 - 95% |

| Buck et al (1986) | Observational | Pooled & apheresis | Washed by Cobe 2991 | 94% for pooled PLT | Saline | 6 | Control: no information washed: 0/207 | 6 patients with a history of severe allergic reactions received 207 washed PLTs, and showed no further allergic reactions. | Within 4 h | PLT count recovery: 88%. 1-h and 24-h CCI were comparable between the two groups. No effects on febrile reaction |

| Azuma et al (2009b) | Observational | Apheresis | Washed by centrifugation | <20 ml (<10%) | M-sol† (hand-made) | 12 | Control: 117/276 washed: 1/156 | 12 patients developed 117 reactions (mostly allergic reactions) after unwashed 276 PLT transfusions. Only one minor allergic reaction was reported after 156 washed transfusions. | Within 1 d | PLT count recovery: 87% (n = 75) Satisfactory CCI and no clinically evident bleeding were observed in washed groups. |

| 2009b | ||||||||||

Plasma-reduced: 60-70% of plasma was removed, and additional solution was supplemented.

Concentrated: 60-70% of plasma was removed, but additional solution was not supplemented.

Washed: more than 90% of plasma was removed.

Control: unmanipulated PLT.

Sodium Citrate: 10 mM, citric acid: 5 mM, dextrose: 209 mM, albumin: 0·7 mM.

77 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 21 mM Na acetate, 15 mM glucose, 9·4 mM Na3 citrate, 4·8 mM citric acid, 44 mM HaHCo3, 1.6 mM MgSO4.

PLT, platelet; CCI, corrected count increment.

The preventative effects of plasma-reduced or concentrated PLTs are significant, although they may be limited.

Washed PLTs are more effective than plasma-reduced or concentrated PLTs.

Residual plasma after PLT washing should be <10% or 20 ml to achieve highly preventative effects.

However, there are some limitations to using washed PLTs. First, washed PLTs are not prepared by blood centres as an approved blood component in any country. Second, washing PLTs is time-consuming; this hampers the number of washed PLTs that can be prepared at one time. Blood centres require high throughput automated devices to produce washed PLTs as an approved blood component. Third, washing weakens the antimicrobial/microbicidal activity of plasma (Hirayama et al, 2011). Fourth, the duration for which the preventative effects last after washing remains unknown. Although these effects seem to last for a day after preparation (Azuma et al, 2009b), the duration of their effectiveness after that remains unclear. Fifth, it is uncertain whether plasma proteins or BRMs, which are probably released from platelet granules, cause allergic reactions. If BRMs are responsible, they would re-accumulate in the PLT components and washing would no longer be effective after a certain point. Sixth, platelet recovery after washing is 80–95% of unwashed PLTs, and the corrected count increment (CCI) may be slightly lower in washed PLTs than in unwashed PLTs, as shown in Table I. Seventh, PLTs may be activated. PLT activation may lead to up-regulation of CD62, resulting in shorter in vivo survival, and enhance the release of BRMs from PLTs, which may cause adverse reactions.

These issues need to be resolved before blood centres begin to routinely supply high-quality washed PLTs. Regarding the last limitation, additive solutions have been developed that can attenuate PLT activation. Adding magnesium and potassium ions to the commercial additive solutions PASII and PASIII completely prevented PLT activation, as evidenced by comparable levels of CD62p expression, BMR release, glucose consumption and lactate production (de Wildt-Eggen et al, 2002; Gulliksson et al, 2003; Shanwell et al, 2003). In addition, M-sol, which contains magnesium and potassium ions, reportedly has attenuating effects on PLT activation (Hirayama et al, 2007). Although there has been no reported study of washed PLTs re-suspended in PASII and PASIII containing magnesium and potassium ions, a study of washed PLTs re-suspended in M-sol has been reported (Azuma et al, 2009b; Table I). Detailed evaluations of each additive solution are needed before making any final conclusions on this issue.

Recently, the Japanese Society of Transfusion Medicine and Cell Therapy issued guidelines (http://www.jstmct.or.jp/jstmct/Document/Guideline/Ref9-2.pdf) for washed PLTs and their preparation in hospitals. These guidelines recommended M-sol as a supplemental solution (Hirayama et al, 2007). However, a solution that is made in-house, such as M-sol, is not approved for producing approved blood components. This issue also needs to be resolved before blood centres prepare washed PLTs as an approved blood component.

Transfusions to IgA- or Hp-deficient patients

Transfusions for IgA- and Hp-deficient patients require special attention. FFP should be IgA- or Hp-free. In Japan, blood centres screen for IgA- and Hp-deficient donors and store a sufficient number of FFP preparations for IgA- and Hp-deficient patients. Deficient donors are registered for FFP donations only. IgA- or Hp-free PLTs and RBCs are usually supplied as washed components to deficient patients. RBCs can be washed up to 3 times to remove as much plasma as possible; however, it is difficult to perform the same procedure with PLTs. In these cases, PLTs may be obtained from registered donors.

Immune tolerance induction to IgA-deficient patients with IgA anaphylactic reactions

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) involves low levels of most or all of the immunoglobulin classes, a lack of B lymphocytes or plasma cells that can produce antibodies and frequent bacterial infections. Patients with CVID frequently develop IgA antibodies that may induce anaphylaxis after intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) preparations or blood transfusions are administered. These patients may develop tolerance to IgA if IgA-depleted IVIG preparations are used. Ahrens et al (2007) induced tolerance in five CVID patients with a history of anaphylaxis by infusing IgA-depleted IVIG preparations that contained only small amounts of IgA, until IgA antibody activity was decreased significantly or became undetectable. Subsequently, all five patients developed complete tolerance to IVIG preparations. Although the precise mechanism underlying tolerance is unknown, the most plausible explanation is that the infused residual IgA molecules in IVIG preparations block IgA antibodies and that high-dose IVIG inhibits IgA antibody production. However, more studies are needed before drawing any final conclusions on this treatment.

Treatment

Although pre-transfusion medications are not effective, most transfusion reactions are easily treated (Geiger & Howard, 2007; Roback et al, 2011). When urticaria occurs, diphenhydramine may be administered. Severe urticarial reactions may require treatment with methylpredonisolone or predonine. Once a severe reaction develops or anaphylaxis occurs, prompt action should be taken to maintain oxygenation levels and stabilize hypotension. Epinephrine may be administered intramuscularly or subcutaneously. If the patient is unconscious or in shock, epinephrine may be given intravenously. If bronchospasm is present, respiratory symptoms may not respond to epinephrine, and adding a beta II agonist or aminophylline may be required.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Plasma protein deficiencies and antibodies are not always evaluated in cases of allergic reactions. Even when evaluated, they are rarely identified; therefore, the cause of the allergic reaction is not specified and the causative relationship between the reaction and the transfusion remains obscure in many cases. This is usually not a problem because allergic reactions are generally self-limiting and respond well to treatment in many cases. However, in life-threatening cases, the pathoaetiology needs to be determined to prevent these reactions during the next transfusion. Underlying diseases, medicines and infections may elicit symptoms like those of allergic reactions. To confirm the causative relationship between a reaction and a transfusion, the tryptase test and the BAT should be useful, although the BAT has only just begun to be used in transfusion medicine, and its usefulness has not been fully evaluated. These tests only assess the involvement of mast cells and basophils in allergy. Because studies on the murine immune system suggest the involvement of neutrophils and monocytes in allergy, tests that assess their involvement may need to be developed.

Regarding recurrent cases, allergic reactions are usually preventable by using washed PLTs and RBCs. Although these practical techniques are beneficial for patients, a fundamental solution in which the exact mechanism of a reaction is identified should be sought, and prevention should then be based on this underlying mechanism.

One of the keys to a solution may be obtained by determining the duration for which washed PLTs retain allergic reaction-preventing capabilities after the washing procedures. If washed PLTs prove to be effective long enough to allow the re-accumulation of BRMs after washing, the BRM-mediated, allergen-independent pathway would be disproved and the allergen-dependent pathway would be affirmed. We would then need to search for plasma protein deficiencies and antibodies other than those we have identified. In addition, an extensive search for other allergens, like food allergens, should be made, although the importance of food allergens is currently quite controversial. In contrast, if washed PLTs are effective for only a short time after washing, this would indicate that BRMs that accumulate in PLT components are responsible. In this case, we would need to focus on identifying the responsible BRMs and determine how these BRMs induce allergic reactions. This would ultimately lead to the development of new strategies for the prevention and treatment of allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs. Rika A. Furuta, Shigenori Tanaka, Kazuta Yasui, Nobuki Matsuyama and Tomoya Hayashi for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Adourian U, Shampaine EL, Hirshman CA, Fuchs E, Adkinson NF., Jr High-titer protamine-specific IgG antibody associated with anaphylaxis: report of a case and quantitative analysis of antibody in vasectomized men. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:368–372. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199302000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens N, Höflich C, Bombard S, Lochs H, Kiesewetter H, Salama A. Immune tolerance induction in patients with IgA anaphylactoid reactions following long-term intravenous IgG treatment. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;151:455–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DM, Blajchman MA, Ditomasso J, Kulczycki M, Keith PK. Passive transfer of peanut hypersensitivity by fresh frozen plasma. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:853–854. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma H, Yamaguchi M, Takahashi D, Fujihara M, Sato S, Kato T, Ikeda H. Elevated Ca²+ influx-inducing activity toward mast cells in pretransfusion sera from patients who developed transfusion-related adverse reactions. Transfusion. 2009a;49:1754–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma H, Hirayama J, Akino M, Miura R, Kiyama Y, Imai K, Kasai M, Koizumi K, Kakinoki Y, Makiguchi Y, Kubo K, Atsuta Y, Fujihara M, Homma C, Yamamoto S, Kato T, Ikeda H. Reduction in adverse reactions to platelets by the removal of plasma supernatant and resuspension in a new additive solution (M-sol) Transfusion. 2009b;49:214–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba Y, Nishida K, Fujii Y, Hirano T, Hikida M, Kurosaki T. Essential function for the calcium sensor STIM1 in mast cell activation and anaphylactic responses. Nature Immunology. 2008;9:81–88. doi: 10.1038/ni1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert JL, Bush RK, Levy MB. Distribution of intact peanut protein and digestion-resistant Ara h2 peptide in human serum and saliva. Journal Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;123:S268. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschini L, Mannucci PM, Federici AB, Coppola R, Guzzoni S, Agostoni A. Posttransfusion anaphylactic reactions in a patient with severe von Willebrand disease: role of complement and alloantibodies to von Willebrand factor. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1995;125:348–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumiza R, Debard AL, Monneret G. The basophil activation test by flow cytometry: recent developments in clinical studies, standardization and emerging perspectives. Clinical and Molecular Allergy. 2005;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch DR, Gifford H. Allergic reaction to transfused cephalothin antibody. Journal of American Medical Association. 1979;241:495–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck SA, Kickler TS, McGuire M, Braine HG, Ness PM. The utility of platelet washing using an automated procedure for severe platelet allergic reactions. Transfusion. 1986;27:391–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1987.27587320530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühring HJ, Simmons PJ, Pudney M, Müller R, Jarrossay D, van Agthoven A, Willheim M, Brugger W, Valent P, Kanz L. The monoclonal antibody 97A6 defines a novel surface antigen expressed on human basophils and their multipotent and unipotent progenitors. Blood. 1999;94:2343–2356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burks AW, Sampson HA, Buckley RH. Anaphylactic reactions after gamma globulin administration in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia. Detection of IgE antibodies to IgA. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314:560–564. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602273140907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells MC, Irani AM, Schwartz LB. Evaluation of human peripheral blood leukocytes for mast cell tryptase. Journal of Immunology. 1987;138:2184–2189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheifetz A, Smedley M, Martin S, Reiter M, Leone G, Mayer L, Plevy S. The incidence and management of infusion reactions to infliximab: a large center experience. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98:1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis M, Schulz-Huotari C, Burger M, Klink I, Umhau M. Evaluation of the performance of Trima Accel® v5.2 for the collection of concentrated high-dose platelet products and concurrent plasma from high platelet count donors, in Germany. Journal of Clinical Apheresis. 2012;27:75–80. doi: 10.1002/jca.21205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewachter P, Castro S, Nicaise-Roland P, Chollet-Martin S, Le Beller C, Lillo-le-Louet A, Mouton-Faivre C. Anaphylactic reaction after methylene blue-treated plasma transfusion. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2011;106:687–689. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dioun AF, Ewenstein BM, Geha RS, Schneider LC. IgE-mediated allergy and desensitization to factor IX in hemophilia B. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1998;102:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsen L, Taaning E, Mynster T, Hvolris J, Drachman O, Nielsen HJ. Bioactive substances in buffy-coat-derived platelet pools stored in platelet-additive solutions. British Journal of Haematology. 1998;10:445–448. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster B, Schwartz LB, Devouassoux G, Metcalfe DD, Prussin C. Characterization of mast-cell tryptase-expressing peripheral blood cells as basophils. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;109:287–293. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraud O, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Cognasse F. Platelets and cytokines: how and why? Transfusion Clinique et Biologique. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2012.02.004. doi:org/ 10.1016/j.tracli.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger TL, Howard SC. Acetaminophen and diphenhydramine premedication for allergic and febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions: good prophylaxis or bad practice? Transfus Medicine Reviews. 2007;21:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliksson H, AuBuchon JP, Cardigan R, van Meer PF, Murphy S, Prowse C, Richter E, Ringwald J, Smacchia C, Slichter S, de Wildt-Eggen J. Storage of platelets in additive solutions: a multicentre study of the in vitro effects of potassium and magnesium. Vox Sanguinis. 2003;85:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JL, Gill JC, Hopp RJ, Evans J, Haire WD. Induction of immune tolerance in a 7-year-old hemophiliac with an anaphylactoid inhibitor. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1995;74:1039–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama F. Recent advances in laboratory assays for nonhemolytic transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2010;50:252–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama J, Azuma H, Fujihara M, Homma C, Yamamoto S, Ikeda H. Storage of platelets in a novel additive solution (M-sol), which is prepared by mixing solutions approved for clinical use that are not especially for platelet storage. Transfusion. 2007;47:960–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama J, Azuma H, Fujihara M, Akino M, Homma C, Kato T, Ikeda H. Comparison between bacterial growth in platelets (PLTs) washed with M-sol and that in PLT-rich plasma. Transfusion. 2011;51:1592–1594. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JF, Baumert JL, Brons PP, Joosten I, Koppelman SJ, van Pampus EC. Anaphylaxis from passive transfer of peanut allergen in a blood product. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:1981–1982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1101692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson SG, Nopp A, Florvaag E, Lundahl J, Söderström T, Guttormsen AB, Hervig T, Lundberg M, Oman H, van Hage M. High prevalence of IgE antibodies among blood donors in Sweden and Norway. Allergy. 2005a;60:1312–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson SG, Nopp A, van Hage M, Olofsson N, Lundahl J, Wehlin L, Söderström L, Stiller V, Oman H. Passive IgE-sensitization by blood transfusion. Allergy. 2005b;60:1192–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L, Winter KM, Hartkopf-Theis T, Reid S, Kwok M, Marks DC. Evaluation of the automated collection and extended storage of apheresis platelets in additive solution. Transfusion. 2012;52:503–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson F, Mancardi DA, Kita Y, Karasuyama H, Iannascoli B, Van Rooijen N, Shimizu T, Daëron M, Bruhns P. Mouse and human neutrophils induce anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1484–1496. doi: 10.1172/JCI45232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson F, Mancardi DA, Zhao W, Kita Y, Iannascoli B, Khun H, van Rooijen N, Shimizu T, Schwartz LB, Daëron M, Bruhns P. Human FcγRIIA induces anaphylactic and allergic reactions. Blood. 2012;119:2533–3544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh T, Mizumoto T, Yasuda N, Koya M, Ohno Y, Uchino H, Yoshimura K, Ohkubo Y, Yamaguchi H. Selective IgA deficiency in Japanese blood donors: frequency and statistical analysis. Vox Sanguinis. 1986;50:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1986.tb04851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafin M, Fuller AK, Savage WJ, King KE, Ness PM, Tobian AA. The impact of apheresis platelet manipulation on corrected count increment. Transfusion. 2012;52:1221–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LD, Case LD, Hurd DD, Cruz JM, Pomper GJ. A prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of acetaminophen and diphenhydramine pretransfusion medication versus placebo for the prevention of transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2008;48:2285–2291. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman S, Chan P, Robillard P. Risks associated with transfusion of cellular blood components in Canada. Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 2003;17:120–162. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2003.50009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koda Y, Watanabe Y, Soejima M, Shimada E, Nishimura M, Morishita K, Moriya S, Mitsunaga S, Tadokoro K, Kimura H. Simple PCR detection of haptoglobin gene deletion in anhaptoglobinemic patients with antihaptoglobin antibody that causes anaphylactic transfusion reactions. Blood. 2000;95:1138–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft D, Hedin H, Richter W, Scheiner O, Rumpold H, Devey ME. Immunoglobulin class and subclass distribution of dextran-reactive antibodies in human reactors and non reactors to clinical dextran. Allergy. 1982;37:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1982.tb02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambin P, Le Pennec PY, Hauptmann G, Desaint O, Habibi B, Salmon C. Adverse transfusion reactions associated with a precipitating anti-C4 antibody of anti-Rodgers specificity. Vox Sanguinis. 1984;47:242–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1984.tb01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama N, Hirayama F, Wakamoto S, Yasui K, Furuta RA, Kimura T, Taniue A, Fukumori Y, Fujihara M, Azuma H, Ikeda H, Tani Y, Shibata H. Application of the basophil activation test in the analysis of allergic transfusion reactions. Transfusion Medicine. 2009;19:274–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K, Wakamoto S, Miyazaki T, Sato S, Fujihara M, Kaneko S, Yasuda H, Yamamoto S, Azuma H, Kato T, Ikeda H. Life-threatening adverse reaction followed by thrombocytopenia after passive transfusion of fresh frozen plasma containing anti-CD36 (Nak) isoantibody. Transfusion. 2005;45:803–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nubret K, Delhoume M, Orsel I, Laudy JS, Sellami M, Nathan N. Anaphylactic shock to fresh-frozen plasma inactivated with methylene blue. Transfusion. 2011;51:125–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K, Szallasi Z, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Mischak H, Mushinski JF, Beaven MA. Ca2 + -dependent and Ca2 + -independent isozymes of protein kinase C mediate exocytosis in antigen-stimulated rat basophilic RBL-2H3 cells. Reconstitution of secretory responses with Ca2 + and purified isozymes in washed permeabilized cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DS, O'Toole J, Montreuil T, Scalia V, Goldman M. Evaluation of particle gel immunoassays for the detection of severe immunoglobulin A deficiency and anti-human immunoglobulin A antibodies. Transfusion. 2012;52:1792–1798. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps RP, Kaufman J, Blumberg N. Platelet derived CD154 (CD40 ligand) and febrile responses to transfusion. Lancet. 2001;357:2023–2024. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roback JD, Grossman BJ, Harris T, Hillyer CD. Technical Manual. Bethesda: American Association of Blood Banks; 2011. p. 744. [Google Scholar]

- Ropars C, Muller A, Paint N, Beige D, Avenard G. Large scale detection of IgA deficient blood donors. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1982;54:183–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougemont A, Quilici M, Delmont J, Ardissone JP. Is the HpO phenomenon in tropical populations really genetic? Human Heredity. 1980;30:201–213. doi: 10.1159/000153127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RP, Maddirala SD, Geiger TL, Pounds S, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, Pui CH, Howard SC. Premedication with acetaminophen or diphenhydramine for transfusion with leucoreduced blood products in children. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;130:781–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler SG. How I manage patients suspected of having had an IgA anaphylactic transfusion reaction. Transfusion. 2006;46:10–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler SG, Mallory D, Malamut D, Eckrich R. IgA anaphylactic transfusion reactions. Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 1995;9:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(05)80026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AP, Taswell HF, Gleich GJ. Anaphylactic transfusion reactions associated with anti-IgA antibody. New England Journal of Medicine. 1969;280:188–193. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196901232800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB. Tryptase from human mast cells: biochemistry, biology and clinical utility. Monographs in Allergy. 1990;27:90–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB, Metcalfe DD, Miller JS, Earl H, Sullivan T. Tryptase levels as an indicator of mast-cell activation in systemic anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;316:1622–1626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706253162603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB, Sakai K, Bradford TR, Ren S, Zweiman B, Worobec AS, Metcalfe DD. The alpha form of human tryptase is the predominant type present in blood at baseline in normal subjects and is elevated in those with systemic mastocytosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96:2702–2710. doi: 10.1172/JCI118337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanwell A, Falker C, Gulliksson H. Storage of platelets in additive solutions: the effects of magnesium and potassium on the release of RANTES, beta-thromboglobulin, platelet factor 4 and interleukin-7, during storage. Vox Sanguinis. 2003;85:206–212. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada E, Tadokoro K, Watanabe Y, Ikeda K, Niihara H, Maeda I, Isa K, Moriya S, Ashida T, Mitsunaga S, Nakajima K, Juji T. Anaphylactic transfusion reactions in haptoglobin-deficient patients with IgE and IgG haptoglobin antibodies. Transfusion. 2002;42:766–773. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada E, Odagiri M, Chaiwong K, Watanabe Y, Anazawa M, Mazda T, Okazaki H, Juji T, O'Charoen R, Tadokoro K. Detection of Hpdel among Thais, a deleted allele of the haptoglobin gene that causes congenital haptoglobin deficiency. Transfusion. 2007;47:2315–2321. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvergleid AJ, Hafleigh EB, Harabin MA, Wolf RM, Grumet FC. Clinical value of washed-platelet concentrates in patients with non-hemolytic transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 1977;17:33–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1977.17177128881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soejima M, Koda Y, Fujihara J, Takeshita H. The distribution of haptoglobin-gene deletion (Hp del) is restricted to East Asians. Transfusion. 2007;47:1948–1950. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strait RT, Morris SC, Yang M, Qu XW, Finkelman FD. Pathways of anaphylaxis in the mouse. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:658–668. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.123302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobian AA, Savage WJ, Tisch DJ, Thoman S, King KE, Ness PM. Prevention of allergic transfusion reactions to platelets and red blood cells through plasma reduction. Transfusion. 2011;51:1676–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimura Y, Obata K, Mukai K, Shindou H, Yoshida M, Nishikado H, Kawano Y, Minegishi Y, Shimizu T, Karasuyama H. Basophils play a pivotal role in immunoglobulin-G-mediated but not immunoglobulin-E-mediated systemic anaphylaxis. Immunity. 2008;28:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untersmayr E, Jensen-Jarolim E. The role of protein digestibility and antacids on food allergy outcomes. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121:1301–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadas P, Gold M, Perelman B, Liss GM, Lack G, Blyth T, Simons FE, Simons KJ, Cass D, Yeung J. Platelet-activating factor, PAF acetylhydrolase, and severe anaphylaxis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:28–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo RR, Adamson JW, Gottschall JL, Snyder EL, Lee W, Houghton J, Elfath MD. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of apheresis platelets stored for 5 days in 65% platelet additive solution/35% plasma. Transfusion. 2010;50:2376–2385. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickery BP, Burks AW, Sampson HA. Anaphylaxis from peanuts ingested by blood donors? New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:867–868. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1106934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas GN, Perkins HA, Fudenberg HH. Anaphylactoid transfusion reactions associated with anti-IgA. Lancet. 1968;10:312–315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas GN, Perkins HA, Yang YM, Basantani GK. Healthy blood donors with selective absence of immunoglobulin A: prevention of anaphylactic transfusion reactions caused by antibodies to IgA. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1975;85:838–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa M, Seghatchian MJ, Lubenko A, Contreras M, Dilger P, Bird C, Thorpe R. Cytokine levels in platelet concentrates: quantitation by bioassays and immunoassays. British Journal of Haemotology. 1996;93:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.4611002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamoto S, Fujihara M, Kuzuma K, Sato S, Kato T, Naohara T, Kasai M, Sawada K, Kobayashi R, Kudoh T, Ikebuchi K, Azuma H, Ikeda H. Biologic activity of RANTES in apheresis PLT concentrates and its involvement in nonhemolytic transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2003;43:1038–1046. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamoto S, Fujihara M, Urushibara N, Morishita K, Kaneko S, Yasuda H, Takayama H, Yamamoto S, Azuma H, Ikeda H. Heterogeneity of platelet responsiveness to anti-CD36 in plasma associated with adverse transfusion reactions. Vox Sanguinis. 2005;88:41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrier I, Lusher JM. Development of anaphylactic shock in haemophilia B patients with inhibitors. Blood Coagulation and Fibrinolysis. 1998;9(Suppl. 1):S125–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss ME, Nyhan D, Peng ZK, Horrow JC, Lowenstein E, Hirshman C, Adkinson NF., Jr Association of protamine IgE and IgG antibodies with life-threatening reactions to intravenous protamine. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;320:886–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904063201402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhoff CM, Sipherd BD, Wylie DE, Toalson LD. Severe anaphylactic reactions following transfusions of platelets to a patient with anti-Ch. Transfusion. 1992;32:576–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32692367205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wildt-Eggen J, Nauta S, Schrijver JG, van Marwijk Kooy M, Bins M, van Prooijen HC. Reactions and platelet increments after transfusion of platelet concentrates in plasma or an additive solution: a prospective, randomized study. Transfusion. 2000;40:398–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40040398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wildt-Eggen J, Schrijver JG, Bins M, Gulliksson H. Storage of platelets in additive solutions: effects of magnesium and/or potassium. Transfusion. 2002;42:76–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters JL, Moore SB, Sandness C, Miller DV. Transfusion of apheresis PLTs from IgA-deficient donors with anti-IgA is not associated with an increase in transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2004;44:382–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2003.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]