1. Introduction

Recent approaches to reduce rural poverty among small farm households include increasing opportunities for off-farm work alongside ongoing efforts to improve agricultural productivity and market access (World Bank 2007). For rural households living at subsistence levels, off-farm work helps to augment farm income, diversify against risk, and enhance returns to education (Abdulai and Delgado 1999; Reardon 1997; Yang 1997). Work outside the agricultural sector accounts for one-third to one-half of rural incomes in developing countries and has continued to increase over time (El-Osta, Mishra, and Morehart 2008; Haggblade, Hazell, and Reardon 2007). Given the importance of off-farm work for combating rural poverty, this paper examines patterns of off-farm employment in a subsistence-level farming community in the Brazilian Amazon.

The literature on rural livelihoods in Latin America has explored how participation in off-farm work is influenced by individual characteristics (i.e. age, sex, and level of education) and features of the household (i.e. size, income, physical capital, and location) (Berdegué et al. 2001; Ferreira and Lanjouw 2001; Murphy 2001; Reardon, Berdegué, and Escobar 2001; Yúnez-Naude and Taylor 2001). We build upon this research by examining the critical role of social capital in securing off-farm work. We also distinguish between low-pay and higher-pay off-farm work, as their effect on reducing poverty differs. This paper draws upon a detailed survey of rural households to analyze individual participation in off-farm employment, within the context of coordinating resources and work at the farm level.

2. Study Region

Our study area is in the agricultural zone south of the city of Santarém in the Brazilian state of Pará. Santarém’s location at the confluence of the Amazon and Tapajós Rivers has made it a key trading center for centuries and attracted several waves of settlers.i Santarém is located at the northern end of the Cuiabá-Santarém Highway (BR-163) and is home to a newly-constructed deep water port. The paving of BR-163 and the opening of the port have increased the region’s importance in the movement and export of products from the interior of the Amazon (including Brazil’s largest soy producing state of Mato Grosso) to international markets.

Land use practices, along with soil quality, have led to precarious small-holder agriculture in the region. The biophysical characteristics of the upland area include weak sandy soils that quickly drain water away from the surface and lead to a lack of accessible water in the dry season (Grubb 1995). With much of the cropland producing poorly, small farm settlers rely on diverse land use strategies, paid labor, and informal activities to secure their livelihoods.ii

At the time of our data collection in 2003, the region was experiencing a soy boom,iii which is restructuring rural and urban labor markets. The growth of an export-oriented soy sector is facilitating the shift from an area dominated by family agriculture to one characterized by mechanized, large-farm agriculture (D’Antona and VanWey 2007). National policies and regional actors have played a key role in the expansion of paid work in the area. National pro-export policies since the late 1990s have supported the completion of massive infrastructure projects (e.g. Cargill’s deep water port and the paving of highway BR-163), funded new agricultural research initiatives, and offered tax credits for the cultivation of crops with high global market prices, such as soy (Futemma 2000; Steward 2007). At the same time, local elites have promoted the entry of soy in Santarém. As early as 1995, local leaders began funding research projects to develop locally-viable soy seed.iv They also stepped in with crucial political support when environmental activists mobilized international attention to try and close down the newly-constructed deep water port (Greenpeace 2006; Steward 2007). The growth of soy agribusiness has created opportunities for paid work on commercial farms and in the nearby expanding urban service sector.

All these changes have occurred in the context of a national labor market deeply divided between formal and informal jobs. While the federal government has established a series of stringent labor and employment laws (Tafner 2006), only a minority of Brazil’s labor force enjoys the benefits and protections entitled to formally contracted workers. Brazil’s rural poor, the population represented in this article, remain concentrated in work outside of the formal sector. As share croppers and daily wage workers, they lack basic wage protection and access to most welfare benefits (World Bank 2003). While the formal sector guarantees unemployment insurance, retirement benefits, paid vacation and bonuses, and a minimum salary, most paid work in our study region is in the informal sector. One unique non-contributory social program that many small-holder farmers can avail is through Brazil’s Regime Geral de Previdência (RGPS).v Through RGPS, retired farmers (both men and women) are eligible to receive a monthly income (Packard 2003).

3. Theoretical Orientation

We treat participation in off-farm employment as an economically-motivated and socially-mediated activity. In most cases, households deploy available human resources to improve chances for survival and increase the collective quality of life, within the constraints of social norms and local opportunities. In this regard, individuals and households residing on the same family farm cooperate to capitalize on strengths and combine assets to maximize income and minimize risk. In addition, the composition of assets—human, social, physical and financial—of a farm property influences the livelihood diversification strategies of households, including the likelihood that individuals work off the farm (Ellis 2000).

However, we argue that human capital and commonly-studied household assets only partially explain participation in off-farm work. We examine two aspects of how these decisions are likely to be socially embedded. First, we consider the role of social networks in linking farm residents to jobs outside the farm property. We also examine if the farm owner’s relationship to other residents on the farm influences their likelihood for participating in off-farm work. After discussing the importance of social capital in securing off-farm work, the remainder of this section examines additional characteristics previously shown to influence patterns of work. In our discussion, when possible, we differentiate between low-pay and higher-pay off-farm work. The factors influencing the likelihood of participating in each type of work differs, as do their social and economic consequences.

Social capital

We define “social capital” as the social context of family and kinship networks, consisting of interpersonal relationships constrained by trust, obligation and other cultural values and norms, through which individuals command scarce resources (including employment) by virtue of their membership in a group (Portes 1998; Zhou 1992). The migration literature highlights how social capital plays a critical role in linking sending and receiving communities, thereby reducing the costs and risks to migrants (Massey 1998). Recent research in rural sociology suggests that social networks, interpersonal trust, and norms of reciprocity are three key components of social capital (Jicha et al. 2011). We focus mainly on the social network aspect of social capital in the relationships that we model. Among small farms throughout much of the world, labor is commonly mobilized through community-level social networks (Berry 1993). In the Brazilian Amazon, family networks are the common source of rural jobs and paid opportunities for farm work are likely to be allocated through existing social relationships.

We posit that having a relation or close friend work off the farm creates an information network and reduces the costs and risks associated with such work. Therefore, knowing another person who works off the farm is likely to increase an individual’s opportunity to do so as well, both in lower-wage and higher-pay off-farm work. However, the network effects will be specific to the type of employment; that is, a family member working off the farm in low-wage work will be helpful for securing low-wage work and not for higher-wage jobs.

In addition, as already mentioned, farm owners are likely to play an influential role in deploying available labor on and off the farm. Individuals more closely related to a farm owner may have greater ability and opportunity to engage in off-farm work, by virtue of their higher status. Alternatively, a property owner and those closely related to the owner are likely to have greater responsibilities on the farm leaving less time to engage in off-farm work. Despite the importance of farm-level relationships, they are rarely incorporated into efforts to model work outcomes in rural settlements. We explicitly test whether a farm owner’s relationship to an individual influences his or her likelihood of participating in off-farm work.

Other key assets: human capital, labor supply, and location

We expect small farm households to deploy labor across different types of work such that they take advantage of differences in human capital to maximize economic and social returns.vi Past research suggests that human capital plays a role in whether someone works off the farm and the type of work that they do (Lanjouw 1999; Ruben and van den Berg 2001; Yúnez-Naude and Taylor 2001). Income, job security and other returns to human capital (such as status) are generally higher in the non-farm sector (i.e., government jobs, the service sector, trade, mining or construction) (López and Valdés 2000). These coveted jobs usually require a higher minimal level of education or skill expertise. In contrast, most low-wage work requires skills and training that are similar to farm work. Therefore, individuals with lower levels of education are likely to remain on the farm or work in the agricultural sector off the farm, while individuals with more education are likely to participate in stable higher-pay work. Since individuals accumulate education, skills, and networks as they age, we expect the likelihood of working off the farm to initially increase with age and decline later in the life course. Participation in off-farm employment is also influenced by social norms, which structure the type of work people do (Ellis 2000; Haddad, Hoddinott, and Alderman 1997). The differentiation of labor by gender in our study region leads most men to concentrate in agriculture and heavy manual labor, while women engage disproportionately in housework, child-rearing, animal care, and less labor-intensive roles. We expect the likelihood of male participation to be higher particularly for low-pay off-farm work, given that most of this work involves manual labor. Past research also suggests that females have much lower levels of participation in off-farm work in the agricultural sector (Ruben and van den Berg 2001). Girls in our study region tend to stay in school longer than boys, who often leave school to provide manual farm labor (Siqueira et al. 2003). This trend likely equips women with skills and credentials important for higher-pay off-farm work.

Along with human capital considerations, the available labor supply and demand influence patterns of work. The labor supply on a farm includes all of the adults and adolescents living on the farm property. A farm family with more adults and adolescents increases the likelihood that basic labor requirements are fulfilled (Keister and Nee 2001; Murphy 2001). In recent decades, the fertility rate in the region has substantially decreased (IBGE 2009).vii Smaller families, in the absence of increased mechanization, make labor shortages more likely and off-farm work more difficult. Small-holder farmers in the region often fulfill labor shortages by having related households or friends co-reside and work on the same property (VanWey and Cebulko 2007). In this situation, the property owner generally plays an influential role in determining labor requirements and the allocation of workers on and off the farm. Along with the number of workers on the property, the presence of dependents affects the available supply of labor. Care taking responsibilities can reduce the time available for other types of work. The presence of a young child may restrict the ability of a care giver (i.e. usually mother) to work off the farm. With regards to the elderly, as mentioned earlier, they are eligible for a pension in Brazil; retired male farmers age 60 and above and females above age 55 may receive a monthly income. By bringing additional income to the farm property, elderly are less dependent on their family members (Carvalho Filho 2008).

The demand for farm labor depends on a variety of characteristics, such as the type of crops grown, the area planted, the types and number of animals raised, and the accessibility of water. The greater the labor needs on a farm, the less likely that adults will work off the farm in low-pay agricultural work. In these instances, those who do work off the farm are more likely to participate in higher-pay work (Murphy 2001).

Other characteristics of farm property create access advantages and increase the likelihood that residents of the property will work off the farm (Bird & Shepherd 2003). Individuals living on farms with better access to transportation infrastructure are more easily able to participate in off-farm work. We expect that road quality will play an important role in determining patterns of low-wage work, since this work often involves local travel within our study region. We also expect that individuals with shorter travel times to the city will be more likely to work in the urban service sector (i.e. with relatively higher-paying jobs), and will have a greater chance of developing and maintaining social networks in urban areas. We do not expect travel time to the city to influence the likelihood of participating in low-pay off-farm work.

4. Methodology and Data

We treat Santarém as a case study to understand patterns of off-farm work in a rural settlement.viii We use a rich data set that includes property, household and individual-level information. The data for the case study were collected through in-person interviews in July through September of 2003; multistage stratified random sampling was used to select farm properties (D’Antona and VanWey 2007; VanWey and Cebulko 2007). On each selected property, the farm owner(s) were interviewed. Many farm properties consist of multiple households and every household on a selected property was interviewed. Male and female heads of household were interviewed separately. The female head of household was asked about demographic characteristics of the household, including information about the education, occupation, marital status and location of all of household members and the women’s living children. The male head of household was asked about land use, agro-pastoral production and other characteristics of the property. If either of these individuals was not available, children or other individuals who were knowledgeable about the topics answered.ix In total, 402 households were interviewed on 244 sample properties.

We restrict our analysis to properties consisting of less than 250 hectares. Our restricted sample therefore includes 241 small farm properties, consisting of 397 households and 1,787 individuals. Given our interest in understanding patterns of work on and off the farm, we further restrict our sample to individuals aged 12 to 59 years old. The upper limit of 59 corresponds with the age that men are able to receive rural retirement income from the government (Carvalho Filho 2008). The lower limit of 12 corresponds with the youngest age that children in the area are involved in off-farm work. With this additional restriction, our sample includes 216 farm properties, consisting of 350 households and 1,092 individuals aged 12–59.x

Operationalization of key concepts

Our dependent variable and key outcome of interest is participation in off-farm work, with three possible outcomes: on-farm work, low-pay off-farm work, and higher-pay off-farm work. We focus on paid employment, and are particularly interested in higher-wage jobs, because of their potential to reduce rural poverty by increasing incomes and connecting workers to important markets and opportunities. This operationalization of work does not cover the entire range of livelihood options, as other informal activities such as handicraft sales may contribute to the incomes of small farms. We define on-farm workers as those individuals who only work on the farm property. We define low-pay off-farm work as any paid activity off the farm that earns a daily wage of less than 15 Brazilian Reals, or approximately $5.22 USD at the July 2003 exchange rate; this value is two times the prevailing daily agricultural wage of 7–8 Reals. Of the 1092 individuals in our restricted sample, 106 individuals (9.7 percent of the sample) participate in low-pay off-farm work. We define higher-pay off-farm work as employment that is associated with a monthly salary, which implies more stable work, or a daily wage greater than or equal to 15 Reals. In our sample, 92 individuals (8.3 percent) participate in high-pay work. We have limited information about off-farm work beyond daily or monthly income. Based on our field experience and examination of the available data, women tend to work in the low-skill service sector and as teachers and government employees. Men in higher-pay jobs work as small machine operators, construction workers, service workers (e.g. drivers or guards), and as technicians. Figure 1 shows work outcomes by sex across age groups. While men and women participate in activities on the farm at similar rates, men work off the farm at higher rates than women across age groups.

Figure 1. Farm work* and off farm work, by gender.

* Farm work includes one or more of the following activities: housekeeping, caring for animals, milking cows, land clearing or maintenance, harvesting, or making flour.

We also look at two aspects of social capital: having a close relative/friend who works off the farm and an individual’s relationship to the farm owner. We operationalize the first concept according to whether an individual has a co-resident on the farm property who works off the farm. We create dummy-coded variables for whether there is another person on the property who works off the farm, and differentiate between higher-pay and low-pay work. Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics and the expected effects of social capital and other key characteristics on work outcomes. Approximately 25.4 percent of households have more than one farm resident working off the property. In addition, 12.6 percent of households have more than one higher-pay off-farm worker, while 11.7 percent of households have more than one lower-pay off- farm worker (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Social Capital and Other Individual and Farm-level Characteristics and Their Expected Effects on Off-Farm Work (N = 1,023 Individuals in 350 Households on 216 Farms, Santarém, Brazil, 2003).

| Descriptive statistics |

Expected effects on off-farm work outcomes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | High-pay off farm |

Low-pay off farm |

| 1. Social Capital (household-level) | ||||

| Another off-farm worker (1=yes) | 0.254 | 0.436 | + | + |

| Another HP off-farm worker (1=yes) | 0.126 | 0.332 | + | none |

| Another LP off-farm worker (1=yes) | 0.117 | 0.322 | none | + |

| Owner of farm (1=yes) | 0.591 | 0.492 | + | + |

| Child of owner (1=yes) | 0.277 | 0.448 | + | + |

| Relative/ friend of owner (1=yes) | 0.131 | 0.338 | − | − |

| 2. Human Capital | ||||

| Age (in years) | 28.980 | 13.448 | + | + |

| Female (1=yes) | 0.452 | 0.498 | + | − |

| Education (0–3 years) (1=yes) | 0.389 | 0.488 | − | none |

| Education (4–6 years) (1=yes) | 0.359 | 0.480 | + | none |

| Education (7 + years) (1=yes) | 0.252 | 0.434 | + | none |

| 3. Labor Supply/Demand on farm | ||||

| No. females 12–18 on farm | 0.699 | 1.010 | + | none |

| No. females 19–54 on farm | 1.500 | 1.287 | + | none |

| No. males 12–18 on farm | 0.787 | 1.437 | none | + |

| No. males 19–59 on farm | 1.972 | 1.717 | none | + |

| Children on property (1=yes) | 0.755 | 0.431 | none | − |

| Senior on property (1=yes) | 0.523 | 0.501 | none | none |

| Property size (hectares) | 31.771 | 42.773 | none | − |

| 4. Location of farm property | ||||

| Region with poor road quality (1=yes) | 0.486 | 0.501 | − | − |

| Travel time to city (min) | 105.880 | 49.200 | − | none |

We operationalize an individual’s relationship to the property owner by mapping property-level relationships through three dummy variables: (1) the property owner’s household; (2) the household of a child of the property owner, or (3) the household of a non-child relative or friend of the owner. Table 1 shows that the majority of households are headed by the property owner (59.1 percent), with households headed by the children of a property owner accounting for over a quarter of the households (27.7 percent) in the sample. Households headed by non-child relatives or friends of the property owner account for 13.1 percent of the sample.

Based on past research, we control for human capital, labor supply and demand, and the location of the farm property. We operationalize human capital by examining an individual’s age, sex, and level of education. Age is both a continuous variable in years and a squared variable, since we expect the likelihood of working off the farm to initially increase and eventually decrease with age. The descriptive statistics illustrate that the mean age of individuals in our sample is 28.98 years (Table 1). With regards to sex, males are the reference category for the dummy-coded variable. The descriptive statistics show that there are a greater number of adult males in our population compared to adult females, with females making up 45.2 percent of the sample (Table 1). Education is represented by three dummy variables: (1) zero to three years of education; (2) four to six years of education; (3) seven plus years of education. The reference group is zero to three years of education. The descriptive statistics illustrate that 38.9 percent of the sample has zero to three years of schooling, 35.9 percent has four to six years of schooling, and 25.2 percent has seven plus years of schooling (Table 1).

With regards to labor supply, we distinguish between adults and adolescents (ages 12–18) on the farm, as many adolescents are not full participants in the household economy.xi We also differentiate the supply of labor by gender. The four continuous variables for the availability of labor include: (1) number of adolescent females; (2) number of adult females; (3) number of adolescent males; (4) number of adult males. The descriptive statistics illustrate that on average, farm properties have less than one (0.67) adolescent female, 1.5 adult females, 0.79 adolescent males, and almost two (1.97) males aged 19–59 (Table 1). We operationalize the demand for care giving, which we expect to reduce participation in off-farm work, through two dummy variables: the presence of seniors and the presence of children aged 0 to 11 on a property. Seventy-five percent of properties have one child or more, while 52.3 percent of properties have at least one senior (Table 1). Property size, which is a continuous variable in hectares, serves as a proxy for the demand for farm labor (Murphy 2001). The mean property size in our sample is 31.8 hectares (Table 1).

Finally, we examine two locational characteristics of the farm property: quality of the surrounding roads and proximity to the city. We operationalize road quality based on the location of the farm property within one of four regions in our study area. We create a dummy-coded variable with the reference area consisting of two regions with better road access via state or federal highways. The descriptive statistics indicate that just under half of the properties (48.6 percent) are in older settlement areas with relatively poorer road access (Table 1). We operationalize proximity to the city based on the stated travel time (in minutes) from the property to the city. We believe that travel time is a better measure of proximity to the city than distance, as some households have access to private transportation, while most use buses. The descriptive statistics suggest that the average travel time to the city is more than an hour and 45 minutes (Table 1).

Modeling Strategy

We explore the characteristics that influence an individual’s likelihood to participate in work off the farm and examine two ways in which social relationships influence this process. We use a multinomial regression model to model three possible outcomes: works on the farm, works off the farm in low-pay work, and works off the farm in higher-pay work. We include individual, household, and property-level characteristics in our analysis.xii The individual characteristics include the human capital variables (i.e. gender, age, and education). The household and property level characteristics include the social capital, labor supply and demand, and location variables. From our restricted sample of 1,092 individuals, our model includes 1,023 individuals; we are missing data on education for 69 individuals. Given the sampling method, we use robust standard errors and cluster at the property level in our regression analysis.

5. Results

Table 2 shows the results from our multinomial regression model. With regards to social capital, two findings are noteworthy. First, we find that having a close relative or friend work of the farm increases an individual’s likelihood for participation in off-farm work. More specifically, if a co-resident works off the farm in a low-pay activity, an individual’s propensity to participate in low-pay off-farm work is substantially higher than without such a co-resident; this pattern holds true for both male and female co-residents, though the effect is stronger with a male co-resident off-farm worker. We also find that if a male co-resident on the farm is employed in higher-pay off-farm work, an individual’s propensity for employment in higher-pay off-farm work is higher than if the co-resident did not work off the farm in higher-pay employment. Based on the regression in Table 2, Table 3 shows predicted probabilities for different work outcomes by select characteristics for a 30 year old with other variables held at their mean values. A 30 year old male’s predicted probability of participating in low-pay off-farm work is seven times greater if a male co-resident is participating in low-pay off-farm work compared to if all co-residents work on the farm property (Table 3, Column 1). The same individual’s predicted probability for participating in higher-pay off-farm work nearly doubles if he has a male co-resident who works off the farm in higher-pay work compared to if all co-residents work on the farm.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression of Work Type: On-Farm, Low-Pay Off Farm, or High-Pay Off-Farm (N = 1,023 Individuals, Santarém, Brazil, 2003).

| Variables | Low-pay work vs. Only on-farm |

High-pay work vs. Only on-farm |

High-pay work vs. Low-pay work |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Capital | |||

| Work-related Soc. Capital | |||

| (reference: no off-farm worker) | |||

| Low-pay F off-farm worker | 1.578*** | −0.634 | −2.212*** |

| (0.557) | (0.667) | (0.644) | |

| High-pay F off-farm worker | 0.292 | 0.425 | 0.133 |

| (0.354) | (0.349) | (0.446) | |

| Low-pay M off-farm worker | 2.668*** | −0.040 | −2.708*** |

| (0.468) | (0.362) | (0.518) | |

| High-pay M off-farm worker | 0.135 | 0.715* | 0.580 |

| (0.329) | (0.401) | (0.491) | |

| Relation to Owner | |||

| (reference: owner) | |||

| Child of owner | −0.945** | 0.415 | 1.360** |

| (0.430) | (0.336) | (0.563) | |

| Relative/ friend of owner | −1.338* | 0.220 | 1.558 |

| (0.804) | (0.463) | (0.972) | |

| 2. Human Capital | |||

| Female | −2.129*** | −1.304*** | 0.825* |

| (reference: male) | (0.403) | (0.273) | (0.481) |

| Age | 0.392*** | 0.354*** | −0.038 |

| (0.076) | (0.064) | (0.098) | |

| Age2 | −0.006*** | −0.004*** | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Education | |||

| (reference: 0–3 years) | |||

| 4–6 years | −0.314 | 0.586* | 0.900** |

| (0.313) | (0.341) | (0.441) | |

| 7 + years | −0.253 | 1.743*** | 1.996*** |

| (0.374) | (0.369) | (0.488) | |

| 3. Labor Supply/Demand | |||

| No. Females 12–18 | −0.154 | 0.062 | 0.217 |

| (0.129) | (0.134) | (0.161) | |

| No. Females 19–54 | −0.046 | 0.098 | 0.144 |

| (0.109) | (0.112) | (0.134) | |

| No. Males 12–18 | −0.084 | 0.116 | 0.200** |

| (0.069) | (0.074) | (0.084) | |

| No. Males 19–59 | 0.072 | −0.301*** | −0.373*** |

| (0.090) | (0.117) | (0.134) | |

| Children on property | −0.176 | 0.059 | .236 |

| (reference: no child) | (.462) | (.341) | (.510) |

| Senior on property | −0.153 | −0.074 | 0.079 |

| (reference: no senior) | (0.298) | (0.281) | (0.371) |

| Property size (hectares) | −0.011*** | −0.006* | 0.005 |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| 4. Location | |||

| Poorer road quality region | −0.484* | −0.246 | 0.237 |

| (reference: region on state hwy) | (0.248) | (0.288) | (0.335) |

| Proximity to city (minutes) | −0.001 | −0.006** | −0.005* |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Constant | −7.380*** | −8.177*** | −0.797 |

| (1.275) | (1.156) | (1.747) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.296 | ||

| Number of observations | 1,023 | ||

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses;

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Table 3.

Predicted probabilities of work outcomes by select individual and household characteristics*

| Co-resident works off-farm?+ (1) |

Relation to farm owner (2) |

Gender (3) |

Education (4) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work outcomes |

NO only on- farm work |

YES, low-pay work (male) |

YES, high-pay work (male) |

Self/ owner |

Child | Non- child relative/ friend |

Male | Female | 0–3 years |

4–6 years |

7+ years |

| On farm | 0.802 | 0.404 | 0.703 | 0.805 | 0.834 | 0.865 | 0.689 | 0.923 | 0.852 | 0.843 | 0.709 |

| Low-pay, off farm | 0.074 | 0.536 | 0.074 | 0.120 | 0.048 | 0.034 | 0.179 | 0.029 | 0.101 | 0.073 | 0.066 |

| High-pay, off farm | 0.124 | 0.060 | 0.223 | 0.075 | 0.118 | 0.101 | 0.132 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.084 | 0.225 |

Predicted values calculated using model in Table 2, for a 30 year old with other variables held at mean values.

For a 30 year old male with other variables held at mean values.

Second, an individual’s relationship to the property owner helps to predict work outcomes in our study region. We find that an individual living in a household headed either by a child of the property owner or by a non-child relative or friend of the property owner is less likely to participate in low-pay off-farm work (Table 2). At the same time, the regression results indicate that an individual in a household headed by a child of the property owner has a greater propensity to work off the farm in higher-pay work relative to low-pay off-farm work. Table 3 column 2 shows the predicted probabilities for different work outcomes based on an individual’s relationship to the farm owner. A 30 year old individual living in a household headed by a non-child relative or friend of the property owner has the highest probability for working on the farm. The same individual living in a household headed by a child of the property owner has the highest probability of working off-farm in higher-pay work. If the same individual lives in the property owner’s household, he or she has a higher probability of participating in low-pay off-farm work compared to counterparts living in other households on the same farm.

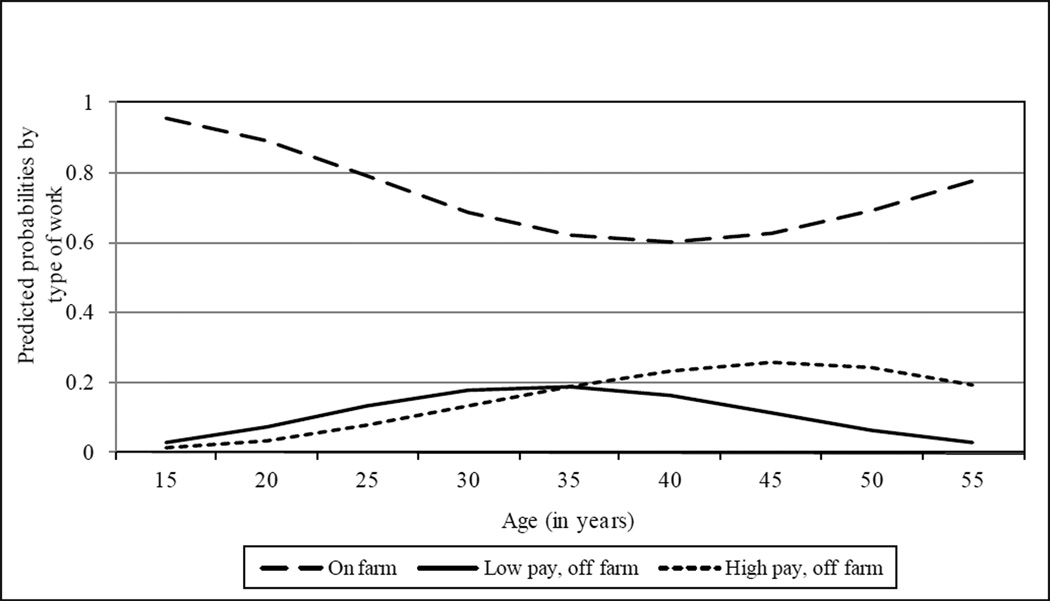

As we would expect from past research, human capital influences work outcomes (Table 2). Age has the expected curvilinear shape for men (Figure 2) and women (Figure 3), with the probability of engaging in low-wage off-farm work peaking around age 35 and in higher-pay off-farm work peaking around age 45.xiii On-farm work predominates for both sexes; however, while a 30 year old female has a 0.92 probability of working on the farm, her male counterpart has 0.69 probability of doing so (Table 3, Column 3).xiv A 30 year old male’s predicted probability of working off the farm in low-pay work (0.179) is greater than his probability of working off the farm in higher-pay work (0.132); the reverse holds true for females (Table 3, Column 3). Women are far less likely to work off the farm, but among those who do they are more are likely to engage in higher-pay work. Education helps to predict the likelihood of participating in higher-pay off-farm work. For a 30 year old with seven plus years of education, the likelihood of working off-farm in higher-pay work (.225) is more than three times greater than the probability of working for low-pay (.066) (Table 3, Column 4). Education is not significant in predicting the likelihood of whether someone works only on the farm versus off the farm in low-pay work.

Figure 2. Predicited probabilities of work outcomes by age for males.

(Predicted probabilities calculated for five year age groups using model in Table 2, with remaining variables held at mean values)

Figure 3. Predicited probabilities of work outcomes by age for females.

(Predicted probabilities calculated for five year age groups using model in Table 2, with remaining variables held at mean values)

Several other findings in Table 2 are worth highlighting. With regards to the labor supply, each additional adult male aged 19–59 on the property decreases an individual’s likelihood of working off the farm in higher-pay work. At the same time each additional adolescent male increases an individual’s likelihood of working off the farm in higher-pay work. The presence of dependents—children or seniors—does not help to predict patterns of work. With regards to labor demand (as measured by property size), individuals living on larger properties are associated with a greater propensity to work only on the farm. The relative effect of property size is more strongly negative on the likelihood of working off the farm in low-pay work. Location also influences an individual’s likelihood of participating in off-farm work. In areas with poor roads, an individual has a greater likelihood of only working on the farm compared to participating in low-pay off-farm work. In addition, as travel time to the city increases, an individual’s likelihood of working off the farm in higher-pay work decreases relative to both on-farm and off-farm low-pay work.

6. Discussion

This paper explores the role of social capital in securing off-farm work among small, subsistence-level farms in a rural settlement in the Santarém region of the Brazilian State of Pará. We differentiate our analysis by type of off-farm work, as the social and economic consequences of low-pay versus higher-pay work differ. Building off past research, we find evidence that human capital (i.e. gender, age and education), labor supply and demand, and the location of the farm property influence patterns of off-farm work. The historical trajectory of our case is heavily shaped by government policies which created settler colonies in the Amazon and more recently facilitated the expansion of commercial agriculture in the region. Therefore, we believe that the results from this paper will have particular relevance for rural settlements in the Amazon, as well as for a broader set of communities experiencing a decline in family agriculture and the expansion of commercial farming.

The findings advance our understanding of how work outcomes on subsistence-level farms are socially-embedded. First, we find evidence for the theory that farm-level social networks help to create an information network that reduces the cost and risks associated with participation in work off the farm property. If another individual on the property works off the farm, an individual has a much higher likelihood of working off the farm in low-pay work. While this trend is particularly strong for low-wage work, it also holds true for higher-wage work among men. The specific policy and investment context of Santarém at this time was arguably conducive to getting low-wage employment and a limited number of higher paying jobs in commercial agriculture, with local government and federal incentives encouraging the expansion of soy production and export facilities. Social connections appear to quickly move these farm-sector opportunities through families. Second, we find that the social position of a household on the farm property structures opportunities for off-farm work, an activity that brings scarce but much needed cash income. Children of the property owner have the highest likelihood of working off-farm in higher-pay work. Individuals living in households headed by a non-child relative or friend of the property owner are less likely to work off the farm in low-pay work; their presence on a farm is to fulfill existing labor needs on the property itself. Our findings suggest farm-level relationships play an important role in shaping patterns of work on and off the farm.

Similar to past research, we find the importance of human capital in securing off-farm work. Individuals with more schooling have a greater likelihood of working off the farm in higher-pay work, while the level of education is unlikely to vary significantly between those who work on the farm and those who work off the farm in low-pay work. With regards to sex, we find that men participate in off-farm work at much higher rates than women. Among those women who do work off-farm, more are likely to engage in higher-pay work, while the reverse holds true for men. We do not, however, find evidence of sex-specific transmission of information. That is, there is not a significant interaction between the sex of the co-resident who works off the farm and the sex of the individual in regression models (results not shown). Instead, there is simply a stronger effect of a male off-farm worker than of a female off-farm worker on the likelihood of any individual working off the farm.

We recognize two possible shortcomings in our analysis. First, an alternative explanation for the difference in higher-pay versus low-pay results across men and women is that the social norms in the region may make it more undesirable for women to work away from the household. In this instance, women will work off-farm only if the opportunity cost of working on the farm is higher (i.e. if the off-farm wages are higher). Second, there is the possibility of reverse causality, such that the work outcome determines the household structure (or another independent variable in our analysis). We hope that by grounding our model in a strong theoretical framework, the empirical analysis offers rich descriptive insights into the processes at work in our study site.

Collectively, the findings suggest a number of general conclusions. On-farm social capital is important for accessing off-farm work in the agricultural sector. This social capital helps to provide cash income for farms through low-wage work, potentially loosening budget constraints and raising standards of living. While such a strategy provides additional income it does not provide a pathway out of poverty. Better jobs give individuals and families both stability and more income, which can be combined with farm work to attain secure livelihoods. Past research has shown that broader social networks, beyond one’s family and close-knit community, are critical for securing higher-paying jobs in the modern economy (Granovetter 1973; Munshi and Rosenzweig 2006; Woolcock 1998).

Increasing opportunities for higher-pay work outside the agricultural sector is an important area for rural development policies. While recent rural development policies affecting our study region have promoted the expansion of commercial agricultural, these changes have displaced family agriculture while creating only a limited number of opportunities for higher-pay work (which tend to employ men). The implementation of bolsa família, which provides government cash transfers to families with the requirement that children stay in school, is likely to increase the future supply of educated rural workers in the region and throughout Brazil.xv A rural population with higher levels of education will create additional demands for higher-pay jobs, particularly among girls in our study region who, on average, are staying in school longer than their male counterparts. Throughout Brazil, rural women participate at higher rates in the non-farm sector. The expansion of the non-farm rural sector is likely to increase prospects for off-farm work for women and the possibilities for higher-pay work more broadly. Therefore, rural development policies that expand work opportunities in the non-farm sector will be crucial for reducing poverty and securing improved rural livelihoods for current and future generations.

Acknowledgments

Grants/ funding information: Leah VanWey (Co-PI) National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH grant #R01-HD3581 “Amazonian Deforestation and the Structure of Households;” Trina Vithayathil, National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program

Footnotes

In the 20th century, there have been three substantial waves of rural settlers in our study region (i.e. in the 1930s, 1950s, and 1970–1980s). The most recent wave of settlers arrived after federal policies in the 1970s provided free land in the Amazon to landless families from other parts of Brazil (Brondizio et al. 2002). Cohorts of homesteaders started arriving and settling in the region, as part of the government’s effort to create a small farm sector in the rainforest and following the construction of the Transamazon Highway (Moran 1981). The study area has been the site of a boom-and-bust-cycle, including rubber (1860–1920), and, most recently, jute (WinklerPrins 2006). Much of this area has experienced corresponding cycles of ownership and use by rural residents and urban elites, with extensive clearing in the 1970s for cattle ranching that also failed (Uhl and Buschbacher 1985).

Informal activities, including micro enterprises that produce bake goods and handicrafts for sale in a local market, are common in the region.

The production of soy was negligible in the Santarém municipality prior to the year 2002. While 200 hectares of land were in soy production in 2002, soy cultivation expanded to 4,600 hectares in 2003, the year the survey was conducted; in 2007, over 15,000 hectares of soy were planted in Santarém (IBGE 2009). While soy production has increased significantly, a fungus affecting soybeans after 2004 and the high prices for agricultural inputs have since challenged the industry.

In 1995, the Pará governor financed a private study on the potential for commercial agriculture in Santarém and neighboring municipalities (Steward 2007). This study played a role in the subsequent implementation of soy pilot projects in the region.

Regime Geral de Previdência (RGPS) is Brazil’s public pension system for workers in the private sector. Since the passage of this legislation in 1991, the program has systematically expanded its reach to rural areas. Special contribution and benefit parameters for rural workers under the RGPS make it easier for farmers to become eligible for old-age pensions. Most rural beneficiaries receive the minimum pension, which is equal to the minimum wage since implementation of the RGPS.

By human capital, we mean the knowledge, skills, resources, health and experiences that an individual possesses and has accumulated (Becker 1993).

In 1980, the state of Pará had a rural total fertility rate of 7.8 and by 2000 it was 4.6. The rural fertility rate in the state of Pará remains higher than Brazil’s national rural fertility rate of 3.5 in 2000 (IBGE 2009).

The case study approach is concerned with the “detailed examination of an aspect of a historical episode to develop or test historical explanations that may be generalizable to other events” (George and Bennett 2005: 5).

Among the farm properties included in this analysis, 19 percent of the properties had proxy respondents.

The twenty-five farm properties excluded from the additionally restricted sample have no 12–59 year olds living on them, but do have elderly residents.

Adults are defined as 19–54 years for women and 19–59 for men; the upper bound corresponds with the gender-specific age threshold for receiving government retirement income.

To account for the possible effects of including household and property-level characteristics in an individual level model, we also ran a series of fixed-effects logit models to simulate a fixed-effects multinomial logit model and found similar results. These results have not been included but can be provided upon request.

Men have a higher probability of working in low-pay jobs relative to higher-pay jobs until age 35; then, the trend reverses (Figure 2). As women age, they have an increasing probability of participating in higher-pay off-farm work relative to low-pay off-farm work (Figure 3).

Table 3 column 3 actually understates the difference between the sexes because women, on average, complete more education than men.

The changing policy context since 2003 suggests that the current generation of school-attending children will attain higher levels of education, as the implementation of the bolsa família program (which consolidated and expanded from existing programs in the mid-2000s; Rocha 2011) provides cash transfers to families with the requirement that children stay in school. Given the importance of education to secure better jobs, the current generation of children will be in an enhanced position to secure coveted higher-pay off-farm jobs.

Contributor Information

Leah VanWey, Department of Sociology, Associate Director, Population Studies & Training Center, Core Faculty, Environmental Change Initiative, Brown University.

Trina Vithayathil, Department of Sociology, Trainee, Population Studies & Training Center, Trainee, Graduate Program in Development, Brown University.

References

- Abdulai A, Delgado CL. Determinants of Non-farm Earnings of Farm-Based Husbands and Wives in Northern Ghana. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 1999;81:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary Stanley. Human Capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [1964] [Google Scholar]

- Berdegué Julio A, Ramírez Eduardo, Reardon Thomas, Escobar German. Rural Nonfarm Employment and Incomes in Chile. World Development. 2001;29:411–425. [Google Scholar]

- Berry S. No Condition Is Permanent. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bird K, Shepherd A. Livelihoods and Chronic Poverty in Semi-Arid Zimbabwe. World Development. 2003;31:591–610. [Google Scholar]

- Brondízio ES, McCracken SD, Moran EF, Siqueira AD, Nelson DR, Rodriguez-Pedraza C. The Colonist Footprint: toward a Conceptual Framework of Deforestation Trajectories among Small Farmers in Frontier Amazônia. In: Wood C, Porro R, editors. Deforestation and Land Use in the Amazon. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press; 2002. pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho Filho IE. Old-Age Benefits and Retirement Decisions of Rural Elderly in Brazil. Journal of Development Economics. 2008;86:129–146. [Google Scholar]

- D’Antona, Álvaro de O, VanWey Leah K. Estratégia para Amostragem da População e da Paisagem em Pesquisas sobre Uso e Cobertura da Terra. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População. 2007;24:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- El-Osta HS, Mishra AK, Morehart MJ. Off-Farm Labor Participation Decisions of Married Farm Couples and the Role of Government Payments. Review of Agricultural Economics. 2008;30:311–332. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Frank. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira F, Lanjouw P. Rural Non-Farm Activities and Poverty in the Brazilian Northeast. World Development. 2001;29:509–528. [Google Scholar]

- Futemma Celia. PhD Dissertation. Bloomington, IN: School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University; 2000. Collective Action and Assurance of Property Rights to Natural Resources: A Case Study from the Lower Amazon Region, Santarém, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- George Alexander, Bennett Andrew. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter Mark. The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;48:1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Greenpeace International. Eating up the Amazon. [Retrieved January 10, 2010];2006 http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/en/media-center/reports/eating-up-the-amazon. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb PJ. Mineral Nutrients and Soil Fertility in Tropical Rainforests. In: Lugo AE, Lowe C, editors. Tropical Forests: Management and Ecology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad Lawrence, Hoddinott John, Alderman Harold. Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Developing Countries. Baltimore, MD & London: John Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Haggblade Steven, Hazell PBR, Reardon Thomas. Transforming the Rural Nonfarm Economy. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. Censo Demografico 1970/2000. [Retrieved January 10, 2010];2009 http://www.ibge.gov.br.

- Jicha Karl A, Thompson Gretchen H, Fulkerson Gregory M, May Jonathan E. Individual Participation in Collective Action in the Context of a Caribbean Island State: Testing the Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Social Capital. Rural Sociology. 2011;76:229–256. [Google Scholar]

- Keister Lisa, Nee Victor G. The Rational Peasant in China. Rationality and Society. 2001;13:33–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lanjouw Peter. Rural Nonagricultural Employment and Poverty in Ecuador. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1999;48:91–122. [Google Scholar]

- López Ramón, Valdés Alberto. Fighting Rural Poverty and Latin America: New Evidence and Policy. In: Ramón López, Valdés Alberto., editors. Rural Poverty in Latin America. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas J. Worlds in Motion. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moran EF. Developing the Amazon. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Munshi Kaivan, Rosenzweig Mark. Traditional Institutions Meet the Modern World: Caste, Gender, and Schooling Choice in a Globalizing Economy. American Economic Review. 2006;96:1225–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy Laura L. Colonist Farm Income, Off-Farm Work, Cattle, and Differentiation in Ecuador’s Northern Amazon. Human Organization. 2001;60:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Packard Truman. Social Insurance of Social Assistance for Brazil's Rural Poor. In: World Bank, editor. Rural Poverty Alleviation in Brazil. Washington D.C.: The World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon Thomas. Using Evidence of Household Income Diversification to Inform Study of the Rural Nonfarm Labor Marker in Africa. World Development. 1997;25:735–747. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon Thomas, Berdegué Julio, Escobar Germán. Rural Nonfarm Employment and Income in Latin America: Overview and Policy Implications. World Development. 2001;29:395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha Sonia. O Programa Bolsa Família: Evolução e Efeitos sobre a Pobreza. Economia e sociedade. 2011;20:113–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ruben Ruerd, van den Berg Marrit. Nonfarm Employment and Poverty Alleviation of Rural Farm Households in Honduras. World Development. 2001;29:549–560. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira Andréa D, McCracken Stephen D, Brondízio Eduardo S, Moran Emilio F. Women in a Brazilian Agricultural Frontier. In: Clark Gracia., editor. Gender at Work in Economic Life. Society for Economic Anthropology Monograph Series, No. 20. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press; 2003. pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Steward Corrina. From Colonization to ‘Environmental Soy;’ A Case Study of Environmental and Socio-Economic Valuation in the Amazon Soy Frontier. Agriculture and Human Values. 2007;24:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tafner Paulo SB. Brasília: IPEA; 2006. [Retrieved March 20, 2012]. Políticas Públicas de Emprego, Trabalho e Renda no Brasil in Brasil—O Estado de uma Nação. http://en.ipea.gov.br/index.php?s=11&a=2006&c=c7. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl Christopher, Buschbacher Robert. A Disturbing Synergism between Cattle Ranch Burning Practices and Selective Tree Harvesting in the Eastern Amazon. Biotropica. 1985;17:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- VanWey Leah K, Cebulko Kara B. Intergenerational Coresidence among Small Farmers in Brazilian Amazonia. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1257–1270. [Google Scholar]

- WinklerPrins Antoinette MGA. Jute Cultivation in the Lower Amazon, 1940–1990: An Ethnographic Account from Santarém, Pará. Journal of Historical Geography. 2006;32:818–838. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock Michael. Social Capital and Economic Development. Theory and Society. 1998;27:151–208. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Agriculture for Development: World Development Report 2008. Washington DC: World Bank; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Rural Poverty Alleviation in Brazil. Washington D.C.: The World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Dennis Tao. Education and Off-Farm Work. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1997;45:613–632. [Google Scholar]

- Yúnez-Naude Antonio, Taylor J. Edward. The Determinants of Nonfarm Activities and Incomes of Rural Households in Mexico, with Emphasis on Education. World Development. 2001;29:561–572. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Min. Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]