Abstract

Macrophages represent an important therapeutic target, because their activity has been implicated in the progression of debilitating diseases such as cancer and atherosclerosis. In this work, we designed and characterized pH-responsive polymeric micelles that were mannosylated using ‘click’ chemistry in order to achieve CD206 (mannose receptor)-targeted siRNA delivery. CD206 is primarily expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells, and upregulated in tumor-associated macrophages, a potentially useful target for cancer therapy. The mannosylated nanoparticles improved siRNA delivery into primary macrophages by 4-fold relative to a non-targeted version of the same carrier (p < 0.01). Further, 24h of treatment with the mannose-targeted siRNA carriers achieved 87±10% knockdown of a model gene in primary macrophages, cell type that is typically difficult to transfect. Finally, these nanoparticles were also avidly recognized and internalized by human macrophages and facilitated the delivery of 13-fold more siRNA into these cells relative to model breast cancer cell lines. We anticipate that these mannose receptor-targeted, endosomolytic siRNA delivery nanoparticles will become an enabling technology to target macrophage activity in various diseases, especially those where CD206 is up-regulated in macrophages present within the pathologic site. This work also establishes a generalizable platform that could be applied for click functionalization with other targeting ligands to direct siRNA delivery.

Keywords: mannose, nanoparticles, macrophages, siRNA, drug delivery, immunotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages perform a spectrum of functions, some of which have cytotoxic effects (i.e., when fighting infection) and others which promote cell growth, matrix remodeling, and wound healing.1 However, the dysregulation of these multifaceted activities can initiate pathogenesis and promote disease progression. For example, in many cancers, significant levels of resident macrophages have been observed, and this has been correlated with poor prognoses.2 This is hypothesized to occur because tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) overexpress angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF, and matrix-remodeling enzymes including cathepsins and metalloproteinases, promoting tumor growth and invasiveness.3 Further, TAMs also secrete immunosuppressive cytokines including IL-10 and TGF-β, which discourage the infiltration of anti-tumor lymphocytes and further promote an environment conducive to unchecked tumor progression.4 Therefore, macrophages potentially represent a viable therapeutic target that can address a major underlying cause of cancer progression. Based on this hypothesis, technologies that enable cell-specific phenotypic modulation of aberrant macrophage activity would be especially high-impact in cancer research.

A promising strategy to reprogram macrophage behavior is through the use of RNA interference (RNAi) therapy. One approach to therapeutically harnessing RNAi involves the delivery of small interfering RNA (siRNA). siRNA is processed by the target cell’s inherent transcriptional regulation machinery, with the ultimate effect of gene silencing through cleavage and degradation of mRNA complementary to the antisense strand of the delivered siRNA duplex.5 By silencing master genes that regulate undesirable macrophage activity, RNAi therapy has the potential to directly block macrophage functions that lead to disease progression. A number of studies in genetically-engineered knockout models suggest that genes within the Jak/Stat pathways drive pathologic macrophage polarization and activity in a variety of diseases.6–9 Recently, Kortylewski et al. showed that siRNA-mediated silencing of Stat3 in tumor-infiltrating leukocytes drove immune-mediated tumor rejection.10 In a related approach, it has also been shown that siRNA-mediated knockdown of CCR2 in monocytes reduces their ability to enter tumor sites, resulting in fewer TAMs and reduced tumor volumes.11 Finally, in a study aimed at reduction of classically-activated, pro-inflammatory macrophages, Aouadi et al. showed that siRNA-mediated silencing of Map4k4 suppressed systemic inflammation by reducing macrophage production of TNFα.12 The authors note that this approach is applicable to autoimmune diseases and atherosclerosis, where classically-activated macrophages promote disease progression. These studies provide strong precedent for use of RNAi to modulate macrophage function and further motivate the broad applicability of macrophage-targeted siRNA nanocarriers to treat a variety of diseases.

Due to their highly degradative phagocytic, endosomal, and lysosomal compartments, delivery and cytoplasmic release of siRNA in macrophages is particularly challenging, especially in primary cells.13 Conventional transfection methods have led to limited success, because they involve chemically-mediated transfection, based on strongly cationic materials which can be cytotoxic and have been largely restricted to the laboratory bench.14 While strategies exist for targeting macrophages at pathologic sites, some of these strategies require prior knowledge of the locations of these sites, in order to design injection routes for local delivery directly into the site of the macrophages.10, 15 For example, intratumoral or peritumoral injections may be useful when treating a primary tumor site but are poorly translatable to the treatment of dispersed, metastatic cancers. Alternative strategies require expensive technologies with uncertain practical clinical applicability, such as macrophage extraction, ex vivo modification, and adoptive transfer;8 antibody-nanoparticle conjugates;16, 17 or custom phospholipids,18 as reviewed elsewhere.19 Very few of these proposed approaches can be practically scaled for pharmaceutical purposes. Some of these methods deliver drugs to multiple cell types non-specifically, and systemic interference with macrophage behavior may lead to unintended side effects, including autoimmune manifestations. Therefore, the clinical translation of macrophage-targeted drug delivery is complicated by barriers including targeting method, synthesis, and cost.

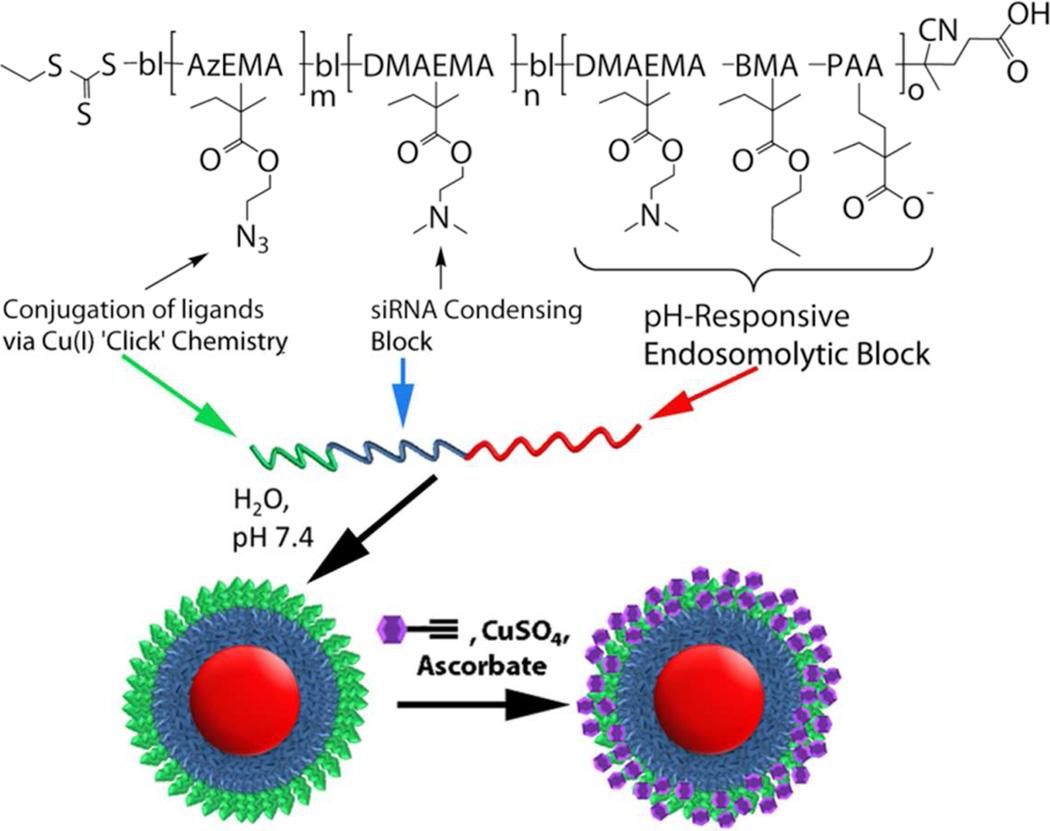

We designed and evaluated a polymeric glycoconjugate that can be assembled into pH-responsive, endosomolytic nanocarriers for macrophage-specific siRNA delivery (Figure 1). These agents expand on a non-targeted polymeric formulation previously reported by Convertine et al.,20 which is capable of mediating the escape of its cargo from the endosomal pathway, due to their ability to disrupt phospholipid membranes at the acidic environment characteristic within late endosomes (pH < 6.5).

FIGURE 1. Smart Polymeric Nanoparticles for Mannose Receptor-Targed Cytosolic Delivery of siRNA.

Schematic representation of the triblock copolymers and formulation into multi-functional nanoscale siRNA delivery vehicles. The blocks include (red) a pH-responsive block that is capable of disrupting endosomes at low pH, (blue) a cationic block for condensation of nucleic acids, and (green) an azide-displaying block for conjugation of targeting motifs (purple) via ‘click’ chemistry.

The macromolecular structure includes a hydrophobic, pH-responsive block, a cationic, siRNA-condensing block, and a terminal block with reactive sites for ‘click’ bioconjugation (Figure 1). These multifunctional polymers were synthesized via reverse addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, which has the advantage of enabling the polymerization of a variety of monomers displaying a wide range of chemical functionalities.21 Additionally, RAFT yields highly monodisperse polymers and is an industrially-scalable method, making it appropriate for pharmaceutical applications. In aqueous media at pH 7.4, the polymers self-assemble into stable micelles that can be surface-functionalized with a wide range of possible molecular structures through the azide-alkyne ‘click’ reaction chemistry. ‘Click’ reactions have been widely employed to perform covalent conjugations for biological applications, due to their orthogonality, specificity, speed, and efficiency.22

Mannose was chosen as the targeting motif, since mannose receptor (CD206) is primarily expressed by alternatively-activated, M2-like macrophages and some dendritic cells.23, 24 In these cells, CD206 mediates the recognition and endocytosis of mannosylated, fucosylated, or N-acetylglucosaminated substrates, which occurs via clathrin-coated vesicles.25 While most macrophages express low baseline levels of CD206, it is upregulated in TAMs, and the potential to directly target this specific macrophage subset via mannose has not been explored.4, 26 Mannose is also readily available at significantly lower costs than most alternative targeting motifs (i.e., antibodies and peptides), improving the practicality of the approach. We believe that coupling mannose-mediated targeting with pH-responsive endosomolytic polymers will lead to a reliable and translatable platform for macrophage-targeted RNAi therapies and investigational reagents.

In this study, the capabilities of the mannose receptor-targeted nanoparticles (ManNPs) for cytosolic siRNA delivery and gene knockdown were evaluated in primary, murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). Specificity of the carriers was examined based on the ability of the glycoconjugated nanoparticles to preferentially deliver siRNA into immortalized human macrophages relative to cancer cell lines. Results support that the described carrier offers significant opportunities for drug and siRNA targeting to TAMs.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

All reagents and materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used as received unless described otherwise. Monomers for radical polymerization, including BMA, DMAEMA, PAA, and AzEMA, were all purified by vacuum distillation and stored at 4°C in clean, inhibitor-free containers. Riboshredder RNase blend was purchased from Epicentre (Madison, WI). Immortalized cell lines were acquired from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cell culture supplies, including media, fetal bovine serum, antibiotics, and non-essential amino acids were obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). The siRNA sequences purchased for transfections were: FAM-labeled anti-GAPDH siRNA (FAM-siRNA; Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) and anti-PPIB siRNA (Integrated DNA Technologies; Coralville, IA). Horse serum was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA).

Synthesis of 2-Azidoethyl methacrylate (AzEMA)

In a 500 mL round-bottom flask, 15.6 g of sodium azide (0.24 mol) was dissolved in 100 mL of nanopure water, followed by the addition of 5.67 mL of 2-bromoethanol (10 g, 0.08 mol; Supplementary Figure S1). After capping with a septum, the reaction was heated to 80°C and allowed to stir overnight, during which the reaction darkens from yellow to orange. Next, the reaction was allowed to cool to room temperature, the product was extracted 4x with 75 mL diethyl ether. Following two extractions, the aqueous phase changed colors from orange to clear. The pooled organic fractions were concentrated by rotary evaporation to yield pure 2-azidoethanol (>90% by HPLC; UV trace at 215 nm), which is a clear, colorless oil (95% yield; 6.66 g : 27.6137g – 20.9532g). 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO): δ (ppm) 3.20 – 3.27 (t, 2H, CH2N3), 3.44 (s, 1H, OH), 3.54 – 3.60 (q, 2H, CH2O). FT-IR (KBr pellet): 3380 cm−1 (broad, O-H), 2100 cm−1 (N3), 1295 cm−1 (C-N), 1050 cm−1 (C-O).

In a round-bottom flask, 10 g of 2-azidoethanol (0.11 mol) was mixed with 30.6 mL of Et3N (22.3 g, 0.22 mol) in 50 mL of CH2Cl2 in a dry ice-acetone bath (−78°C; Supplementary Figure S1). The reaction vessel was capped with a septum and degassed by alternating evacuation of the vessel and equilibration with nitrogen gas, 6x. Next, 8.6 mL of methacryloyl chloride (9.2 g, 0.088 mol) was injected into the system dropwise, and the reaction proceeded overnight (Caution: azide compounds may become shock-sensitive above 75–80°C, and this step is highly exothermic). The dry ice-acetone bath was allowed to warm to room temperature during this reaction. The crude product was extracted 3x with 1N hydrochloric acid to remove excess Et3N, extracted 2x with 1N aqueous NaOH, and precipitated in nanopure water. After drying the organic fraction over MgSO4the product was concentrated under rotary evaporation to yield a dark red-orange liquid, which was further distilled under high vacuum to produce pure 2-azidoethyl methacrylate. RAFT polymerization kinetics of AzEMA are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 1.97 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.5 (t, 2H, CH2N3), 4.33 (t, 2H, CH2O), 5.62 (s, 1H), 6.18 (s, 1H).

Synthesis of alkyne-functionalized mannose

The reaction diagram has been shown in Supplementary Figure S3A. In a round-bottom flask, 11 g of D-mannose (60 mmol) were dissolved into 30 mL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). To activate the sugar into a nucleophile, 10 mL Et3N (triethylamine; 72 mmol) was added to the reaction, prior to the addition of 5 g propargyl chloride (67 mmol). After flushing the reaction with argon, the reaction proceeded for 24 h at 40°C. Excess reagents were removed by 5X extraction into diethyl ether. The remaining ether-insoluble phase was dissolved into nanopure water and further extracted 5X with dichloromethane to remove other byproducts and DMSO. The product was flash-frozen in liquid N2 and lyophilized. HPLC characterization, 1H- and 13C-NMR are presented in Supplementary Figure S3B–D.

RAFT Polymerizations

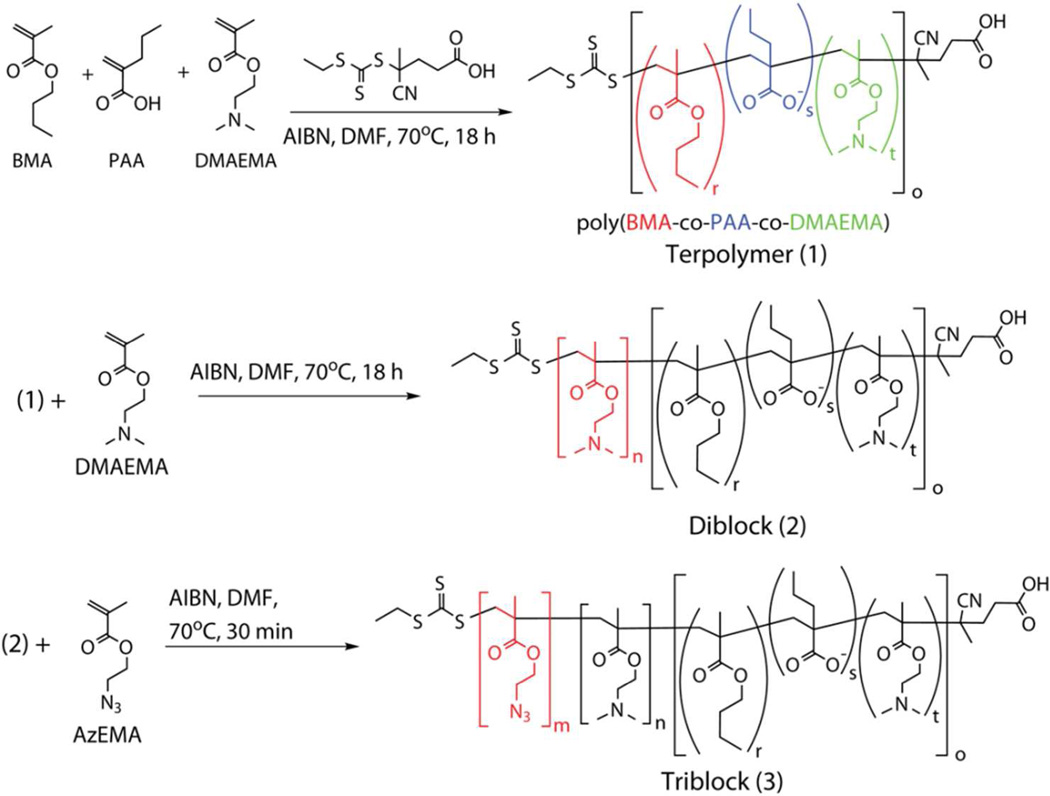

Synthesis of the RAFT chain transfer agent (CTA) 4-cyano-4-(ethylsulfanylthiocarbonyl) sulfanylpentanoic acid (ECT) and 2-propylacrylic acid monomer have been described in detail previously.20, 27 Block copolymers were synthesized based on the scheme shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. RAFT Polymerizations.

Synthetic scheme for RAFT polymerization of triblock copolymers composed of blocks of 2-azidoethyl methacrylate (AzEMA), 2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA), and the DMAEMA-co-BMA-co-PAA terpolymer (butyl methacrylate = BMA; 2-propylacrylic acid = PAA).

Polymerization of the 47%BMA-25%PAA-28%DMAEMA terpolymer (1 in Scheme 1; compositions based on 1H-NMR of the product) was conducted at 70°C under N2 for 18 h with DMF as the solvent (90 wt% in feed), an initial monomer to CTA molar ratio of 100, and a CTA to initiator molar ratio of 10. After rapidly cooling the reaction in an ice bath, the organic mixture was mixed 1:1 (by volume) with aqueous HCl at pH 2, which initially results in a turbid mixture that quickly turns clear-yellowish. Next, the polymer was precipitated 7x in hexanes and 2x in diethyl ether to remove residual, unreacted monomers. Finally, the polymers were dialyzed across 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane (Pierce, Rockford, IL) against nanopure water (pH 5) overnight. Lyophilization yielded pure terpolymer, which was a yellowish powder (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of Polymers Synthesized via RAFT Polymerization

| Polymer | Abbreviation | dn/dc (mL/g) a |

Target Mn (Da) |

Mn (Da) b |

Mw (Da) b |

PDI | Dh (nm) |

ζ-Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA) c | Terpolymer | 0.081 | 14000 | 11400 | 13900 | 1.22 | ||

| poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA) | Diblock | 0.049 | 21000 | 16800 | 20700 | 1.23 | 32.2 ± 6.8 | 15.0 ± 5.3 |

| poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA)-blpoly(AzEMA) | Triblock | --- | 22000 | 22300 | 28900 | 1.29 | 28.0 ± 1.5 | 19.6 ± 11.7 |

Measured in off-line batch mode in a Shimadzu RID-10A differential refractive index (dRI) detector, with DMF + 0.1M LiBr as the solvent.

Measured via gel-permeation chromatography with MALS and dRI in-line with columns.

Terpolymer was insoluble in aqueous buffer at pH 7.4, so no Dh or ζ-potential could be measured via DLS.

The same monomer:macroCTA:I molar ratios, and 90 wt% DMF conditions were used to polymerize the DMAEMA block onto the terpolymer macroCTA (1). To purify the poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA) diblock copolymers (2 in Scheme 1; henceforth referred to as ‘Diblock’), the reaction was precipitated in diethyl ether at −20°C for 1h, and then pelleted by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min. The polymer was dialyzed against deionized water for 48 h using 10kDa-MWCO membrane, and lyophilization yielded a light yellow powder.

Finally, the AzEMA block was polymerized from the diblock (2) to form poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA)-bl-poly(AzEMA) triblock copolymers (3 in Scheme 1; henceforth referred to as ‘Triblock’) according to a similar reaction conditions. This mixture was then dialyzed against nanopure water across 10kDa MWCO membrane overnight to yield pure triblock. The triblock copolymer was dissolved in deionized water at 1 mg/mL and stored at −20°C until ready for use in ‘click’ reactions.

1H-NMR spectra for all polymers are shown in Supplementary Figure S4.

Mannose ‘Click’ Functionalization

In a scintillation vial, 1 mL of poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA)-bl-poly(AzEMA) copolymer (3; 1 mg/mL in nanopure H2O) was mixed with 6 mg alkyne-functionalized mannose (27.5 mmol). After the addition of CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate to final concentrations of 1 mM and 5 mM, respectively, the reaction was allowed to proceed at 37°C on an orbital shaker in the dark for 48 h. Excess copper was removed by treating the crude product with Chelex 100 Resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The product was filtered through a 0.45 µm Teflon filter to remove the resin, and then dialyzed through a 2 kDa-MWCO membrane against deionized water to remove excess reactants. Lyophilization yielded the ManNPs, which were reconstituted in nuclease-free water at 1–4 mg/mL before use in experiments. 1H-NMR characterization of the micelles before and after ‘click’ chemistry is shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

siRNA Protection Experiments

50 pmol FAM-labeled siRNA was complexed with mannosylated nanoparticles at N:P (NH+:PO4−) ratios of: 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, and 4:1. Ratios were calculated by using the concentration of NH+ (based on the degree of polymerization of the DMAEMA homopolymer block) and PO4− (based off the number of siRNA base pairs). Because the pKa of the DMAEMA occurs at around pH 7.5, we assumed that the DMAEMA polymer block was 50% charged for the calculation of N:P ratios. The complexes were loaded onto a 2% agarose gel containing 1.5 µM ethidium bromide.

The RNase protection experiment was performed on siRNA complexes with either untargeted nanoparticles comprised of the diblock copolymers or mannosylated nanoparticles (1:2 or 4:1 N:P ratios), as described elsewhere.28

Hemolysis Assays

Assays were performed as described previously.29 Briefly, human blood samples were obtained from consenting, anonymous, healthy adults under a Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol. Plasma was removed and RBCs were washed with 150 mM NaCl. RBCs were ultimately diluted into phosphate buffers adjusted to pH 5.6, 6.2, 6.8, or 7.4, and percent hemolysis in these buffers was assessed for polymers at concentrations of 1, 5, and 40 µg/mL. PBS (negative control) or 20% Triton X-100 (positive control) were used as controls. Polymer-RBC solutions were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1 h, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and supernatants transferred into a new plate. The percent RBC lysis was quantified based on absorbance at 450 nm relative to samples treated with Triton X-100 (assume 100% lysis) and PBS (to subtract background absorbance).

Animals and Cell Lines

Animal work was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were on an FVB background strain. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated from tibiae and femurs immediately after sacrificing the mice and cultured as described elsewhere.30 Cells were seeded at 300,000 cells/cm2 for all experiments. Detailed information on culturing of immortalized cell lines can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Transfections

ManNP formulations were prepared as described above, and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX® (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions as a commercially-available benchmark. Cells were rinsed twice with PBS and given serum-free medium, which is composed of DMEM with 4.5 g/L glucose, 1 U/mL penicillin, 1 µg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. Complexes were then added to the wells such that the final concentration of siRNA in the wells was 50 nM (ten-fold dilution from stock). For some experiments, cells were co-incubated with complexes and 100 mg/mL free D-mannose (Sigma-Aldrich) to examine CD206-dependence of nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery. At set time points, wells were rinsed with PBS and processed according to the desired experiment as described below.

Transfected cells were analyzed for cell viability using a Live-Dead kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of live and dead cells was done by flow cytometry.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cell samples using the RNeasy Kit and QiaShredder columns (Qiagen). After the removal of genomic contamination through DNAse treatment (DNA-free kit, Life Technologies), cDNA libraries were constructed using a reverse transcriptase kit (Life Technologies).

For qRT-PCR, Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). PPIB sense: 5’-TTCCATCGTGTCATCAAG-3’ and antisense: 5’-GAAGAACTGTGAGCCATT-3’. GAPDH sense: 5’-TGAGGACCAGGTTGTCTCCT-3’ and antisense: 5’-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTAT-3’. Quantitative RT-PCR was done using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. Details on data analysis for relative GAPDH expression can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a BD FACSCalibur system (Franklin Lakes, NJ), operated via a BD Cellquest Pro (version 5.2) software. The FL1 channel (emission filter at 530 ± 15 nm) was used for the quantification of FAM emission of each cell.

Confocal Microscopy

Transfections were performed as described above for 1, 2, or 4 h. To prepare cells for confocal microscopy, they were washed with PBS, fixed for 15 min with 10% buffered formalin, rinsed 3x with PBS, and then stained with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 10 min. After rinsing cells 3x with PBS, slides were mounted with the Invitrogen ProLong Antifade kit. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM 710 system (Oberkochen, Germany). Image processing is described in the Supplementary Information.

Statistical Analysis

For all experiments, statistical significance was assessed using the unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate and indicated in the text, with p<0.05 considered significantly different.

RESULTS

Modular Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of Mannosylated siRNA Delivery Vehicles

The synthesis of the mannosylated delivery vehicles was successfully completed through three stages: (I) the polymeric components were synthesized in three sequential iterations of RAFT polymerization and purification (Figure 1, Scheme 1), (II) alkyne-functionalized mannose was separately synthesized (Supplementary Figure S3), and (III) the polymers from (I) are formed into micelles and reacted with the alkyne-functionalized mannose from (II). These steps result in immobilization of mannose onto the micelle corona through reaction with the distal azide groups via ‘click’ chemistry (Figure 1).

The polymers that make up the ManNPs were synthesized via RAFT polymerization. These modules include a pH-responsive block (Figure 1, red), a cationic block for condensing nucleic acids (blue) and an azide-presenting block (green) for the attachment of alkyne-functionalized ligands. First, a ~14 kDa random terpolymer block composed of 47% butyl methacrylate (BMA), 25% 2-propylacrylic acid (PAA), and 28% 2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA) was synthesized (Scheme 1; Table 1). The percentages represent molar composition of each monomer in the copolymer structure, as determined by 1H-NMR (Supplementary Figure S4). The terpolymer forms a turbid suspension on exposure to aqueous media at pH 7.4, but dissolves effectively when pH is lowered to < 6.0, consistent with the pH-sensitive characteristics of this block.

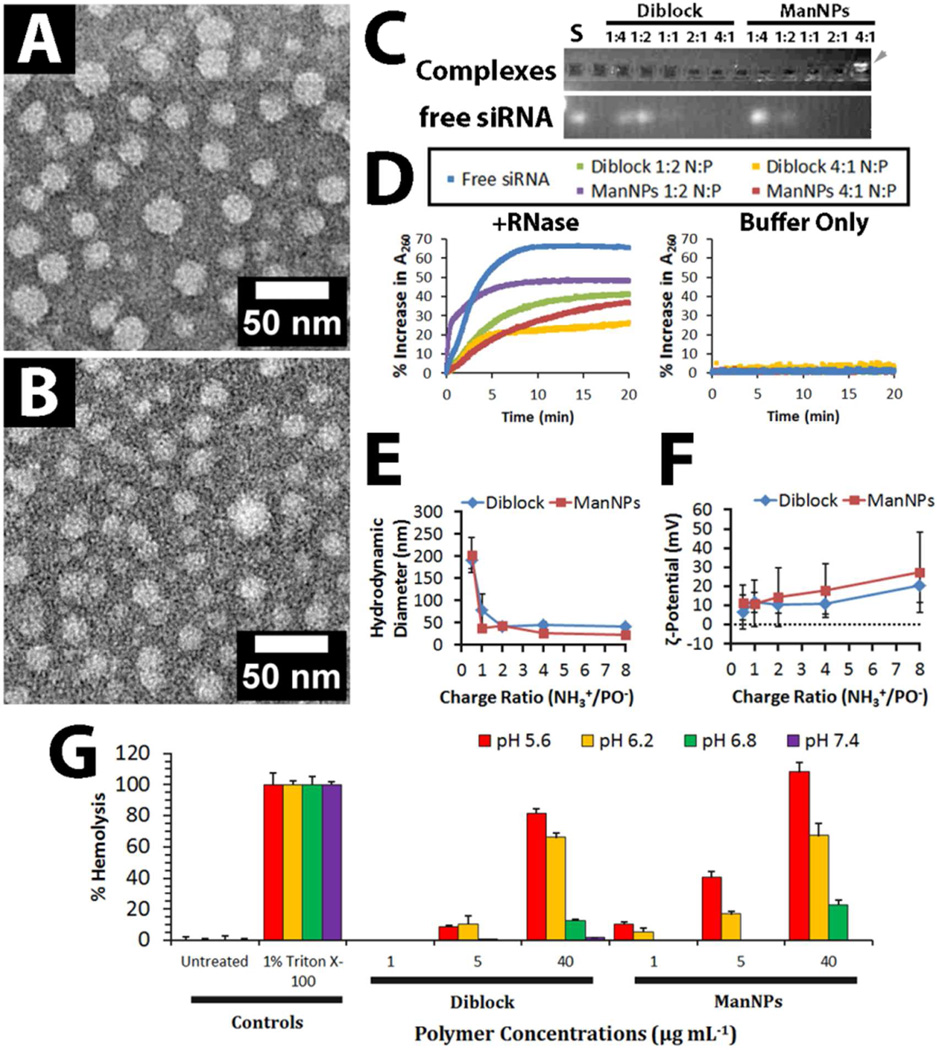

To form a hydrophilic, corona-forming segment, a cationic DMAEMA block (8.9 kDa by 1H-NMR) was polymerized from the terpolymer macro-CTA, yielding a diblock copolymer (22.8 kDa; Figure 1, red and blue; Table 1). This diblock copolymer self-assembles into micellar nanoparticles on exposure to aqueous media (Figure 2A), consistent with previous work by others.20, 31–33 Diameters of the diblock copolymer micelles were measured at 13.0 ± 6.1 nm by TEM and 32.2 ± 6.8 nm by DLS.

FIGURE 2. Morphologic and Functional Characterization of Micelles composed of Diblock Copolymers and Mannosylated Triblock Copolymers.

(A–B) Uranyl acetate-counterstained transmission electron micrographs of (A) micelles of diblock copolymers (See 2 in Scheme 1), which had an average diameter of 13.0 ± 6.1 nm (n = 367). (B) ManNPs had an average diameter of 9.7 ± 6.2 nm (n = 415). Scale bars = 50 nm. (C) Gel retardation assay of siRNA-loaded ManNPs confirmed increased complexation of siRNA with increasing NH+:PO− ratios. Free FAM-labeled siRNA (S) appears as a control. The cationic ManNPs migrate in the opposite direction from the siRNA (gray arrowhead), consistent with their opposing charges. (D) Protection of siRNA from degradation by RNases. Micelle/siRNA complexes were incubated with RNase cocktails. RNase-mediated degradation of siRNA was characterized by a hyperchromic effect at 260 nm, and within 10–15 min, all siRNA in each sample has completely degraded as signified by asymptotic behavior of the results. siRNA and micelle/siRNA complexes which were left in buffer without RNases did not exhibit this hyperchromic effect. (E–F) Dynamic light scattering was used to analyze the (E) hydrodynamic diameters and (F) ζ-potentials of the polymeric micelles following complexation with siRNA. (G) Both polymers exhibit pH- and concentration-dependent hemolysis, with minimal disruption of erythrocyte phospholipid membranes at physiologic pH, but increased disruption at pH ranges mimicking endosomal pH (pH < 6.5). Error bars represent standard deviation of 4 replicates.

Finally, an azide-presenting block composed of 2-azidoethyl methacrylate (AzEMA) was extended from the DMAEMA terminus of these polymers (Supplementary Figure S4). The synthetic route for AzEMA (Supplementary Figure S1) was modified from published schemes for the synthesis of 3-azidopropyl methacrylate, a similar monomer.34, 35 The controlled polymerization kinetics of AzEMA have also been shown here (Supplementary Figure S2).

The resulting triblock copolymers retained the ability to self-assemble into micelles in aqueous media. Morphologically, the triblock copolymers are expected to form assemblies as depicted in Figure 1, where the azide-presenting block effectively shields the DMAEMA block in the final micellar structures. Because addition of the final, AzEMA block to the base diblock leads to a 4 nm decrease in the hydrodynamic diameter of the resulting micelles and a slight increase in ζ-potential (Table 1), NMR spectra of the micelles were obtained in D2O in order to better understand the particle morphology in aqueous environments (Supplementary Figure S4). The base diblock micelles (poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA); 2) featured peaks in chemical shift regions characteristic of pure poly(DMAEMA), while the micelles composed of the triblock (poly(BMA-co-PAA-co-DMAEMA)-bl-poly(DMAEMA)-blpoly( AzEMA); 3) produced peaks corresponding to the azido-protons in addition to poly(DMAEMA) peaks (Supplementary Figure S4–5). Therefore, micelles consisting of the diblocks display a corona of DMAEMA, while the triblock copolymers form micelles that present azide groups at their corona, enabling the facile immobilization of alkyne-functionalized ligands onto the micelles.

The synthesis of alkyne-functionalized mannose (Supplementary Figure S3A) was adapted from a synthetic scheme for derivatized sugars presented by Plotz and Rifai.36 The resulting NMR spectra of the product indicated the successful alkyne-functionalization of the monosaccharide (Supplementary Figure S3C–D). HPLC confirmed that the product is 70–80% pure following synthesis. No further purification was done, and non-functionalized mannose was subsequently removed via dialysis of the final ManNPs.

Following the ‘click’ reaction to functionalize the polymers with mannose, the polymers retained the ability to form micellar nanoparticles, similar to those formed by the diblock copolymers lacking the azide block and mannose (Figure 2A–B). The ManNPs exhibited diameters of 9.7 ± 6.2 nm by TEM and 21.8 ± 2.6 nm by DLS. The ManNPs also exhibited a distinct NMR signature compared to that of the micelles made of triblock copolymer before the ‘click’ mannosylation reaction (Supplementary Figure S5). This is particularly evident in the 3.2–3.7 ppm region, where the appearance of peaks corresponding to mannose is consistent with the success of the ‘click’ reaction.

ManNPs Form Complexes with siRNA and Protect Cargo from Degradation

Like the diblock copolymers, the completed ManNPs are able to complex siRNA in an N:P ratio-dependent fashion as evidenced by a gel retardation assay (Figure 2C). The free, uncomplexed siRNA band apparent in the gel decreased in brightness with increased N:P. We also performed experiments to characterize the ability of ManNPs to protect siRNA cargo from nuclease degradation (Figure 2D). In this study, the degradation of siRNA results in a hyperchromic effect, which is characterized by increased sample absorbance at 260 nm.28 The 65% increase in Abs260 of free siRNA within 10 min of RNase treatment is a demonstration of this effect and is used as a positive control. The same siRNA incubated in buffer alone did not exhibit this trend, confirming that RNase activity is necessary for the hyperchromic effect. Both polymers were able to protect their cargo from rapid degradation by RNases, and this ability is elevated at higher N:P ratios.

Finally, dynamic light scattering confirmed that, the siRNA-polymer complexes increased in hydrodynamic diameter with decreasing N:P (less polymer per siRNA, from 8:1 towards 1:2; Figure 2E). However, at N:P < 2 these complexes became less stable, and > 100 nm diameter clumps were measured. Decreasing N:P ratios also corresponded with decreasing nanoparticle ζ-potential (Figure 2F). Both polymers formed complexes with siRNA which exhibited ζ-potentials of < +25 mV, but these complexes remain colloidally stable if left at room temperature for at least 24 h without any observable flocculation. This suggests that the nanoparticles may be good candidates for in vivo applications.

ManNPs Exhibit pH-Dependent Hemolysis, and are Cytocompatible

We next sought to investigate the ability of the ManNPs to create pH-dependent membrane disruption of red blood cells as a surrogate measure for escape from acidified endosomes following endocytotic uptake. Erythrocyte hemolysis assays are commonly employed to model polymer-endosome interactions because relative membrane disruption can be quantified through the release of hemoglobin from the cells (Figure 2G).29 Both the diblock and the ManNPs did not cause significant levels of hemolysis at pH 7.4 (1.8 ± 2% and 0.0 ± 0.1%, respectively, at 40 µg/mL dose, relative to detergent-treated erythrocytes; n = 4). However, as the environmental pH was decreased to 6.2, significantly higher hemolysis was measured (66.1 ± 2.7% and 67.3 ± 7.6% for diblocks and ManNPs, respectively). This effect was even greater at pH 5.6 (81.5 ± 3.1% for diblock, 108.2 ± 6.1% for ManNPs), which is similar to pH ranges encountered in late endosomes and lysosomes.29 These data suggest that, during circulation, the nanoparticles are unlikely to cause adverse effects due to cell membrane lysis. Importantly, these results also suggest that, following endocytosis, the polymeric components will be able to facilitate pH-dependent disruption of endosomal membranes and cytosolic delivery of the cargo.

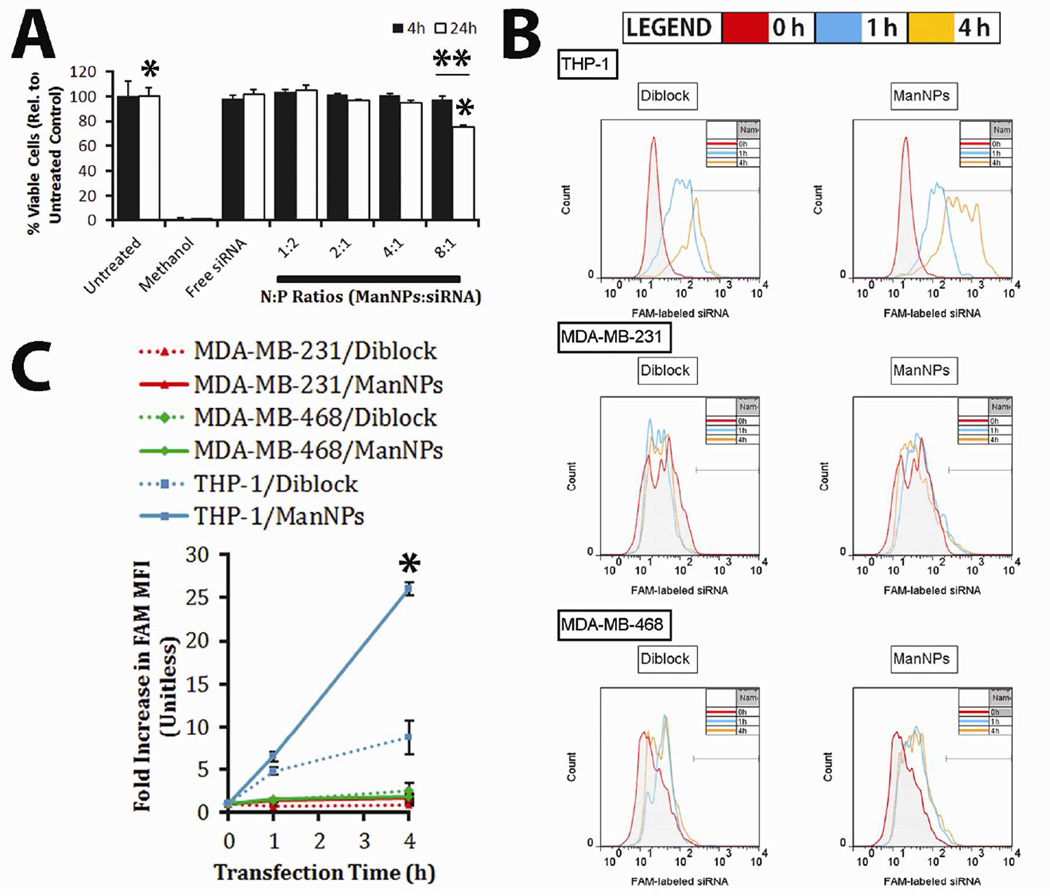

To further demonstrate that the polymers do not cause significant cytotoxicity under physiologic pH conditions, immortalized human THP-1 macrophages were incubated with siRNA-loaded ManNPs at various N:P ratios, and cell viability was assessed via calcein AM/ethidium homodimer incorporation at 4 or 24 h after ManNP delivery. Experimental groups were quantified via flow cytometry relative to untreated cells (100%) or methanol-killed cells (set to 0%; Figure 3A). For all N:P ratios investigated, negligible cytotoxicity was observed at 4 h of treatment. However, at 24 h, 76 ± 1% of the cells treated at the 8:1 N:P ratio remained viable, indicating that prolonged treatment of BMDMs with ManNPs/siRNA at this charge ratio resulted in mild but significant levels of cytotoxicity (*,** p < 0.01; n = 3). The 4:1 N:P ratio was selected for further experiments based on previous precedent20, 27, 37 and because it did not result in significant cytotoxicity at 24 h.

FIGURE 3. ManNPs are Cytocompatible and Selectively Enhance siRNA Delivery into Immortalized Human Macrophages.

(A) Cytotoxicity assay of immortalized THP-1 macrophages, treated with ManNPs complexed with siRNA at various N:P ratios. Error bars represent standard deviation from 3 experiments (*,** p < 0.01; n = 3). (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms of THP-1, MDA-MB-231, or MDA-MB-468 cells at 0 (red), 1 (blue), or 4 h (orange) after transfection with FAM-siRNA loaded into diblock micelles (left column) or ManNPs (right column). (C) Mean fluorescence intensities of all of the groups in (B) have been quantified and shown. Error bars represent standard deviation of n = 3 experiments. ManNPs enhanced siRNA delivery to macrophages up to 26-fold over two model breast cancer cell lines, and 3-fold in macrophages relative to untargeted diblock carriers, as measured via flow cytometry. (*p < 0.01 vs. all other treatment groups at 4 h timepoint).

Relative to Non-targeted Diblock Micelles, ManNPs Enhance siRNA Delivery into Human Macrophages, but not into Cancer Cells

To examine the potential of using the ManNPs to selectively target TAMs, ManNPs loaded with FAM-siRNA were incubated with immortalized human macrophages (THP-1) or human breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231 & MDA-MB-468) for up to 4 h. Cellular internalization of the siRNA was assessed via flow cytometry (Figure 3B–C). All measurements were normalized against the inherent FAM-intensity measured in untreated cells. As controls, cells treated with siRNA-loaded micelles made with the diblock copolymers were also measured. For both breast cancer cell lines, modest intracellular delivery of FAM-siRNA/ManNPs was observed with either carrier investigated (diblocks or ManNPs). both cell types experienced approximately a two-fold increase in FAM mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) over the 4 h study period. With the macrophages, the same treatment period led to a 26-fold increase in the FAM MFI of the cells, confirming that these cells preferentially internalize the constructs relative to the model cancer cell lines (Figure 3C; *p < 0.01 vs. all other treatment groups at 4 h). Further, ManNPs facilitated a 3-fold increase in siRNA delivery to the macrophages, relative to the diblock micelles.

ManNPs Mediate CD206-Dependent Intracellular siRNA Delivery and Target Gene Knockdown in Primary Murine Macrophages

siRNA delivery and gene knockdown were examined in primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). Within 4 h of siRNA administration, ManNPs improved delivery of FAM-siRNA into macrophages by more than 40-fold relative to free siRNA or fourfold relative to the untargeted, diblock copolymers (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure S6; p < 0.01). Notably, the uptake of ManNPs can be partially blocked via co-administration with D-mannose, indicating that internalization of the ManNPs is mediated by the mannose receptor CD206. These phenomena are also observed when transfections are performed in serum-containing media (Figure 4A right).

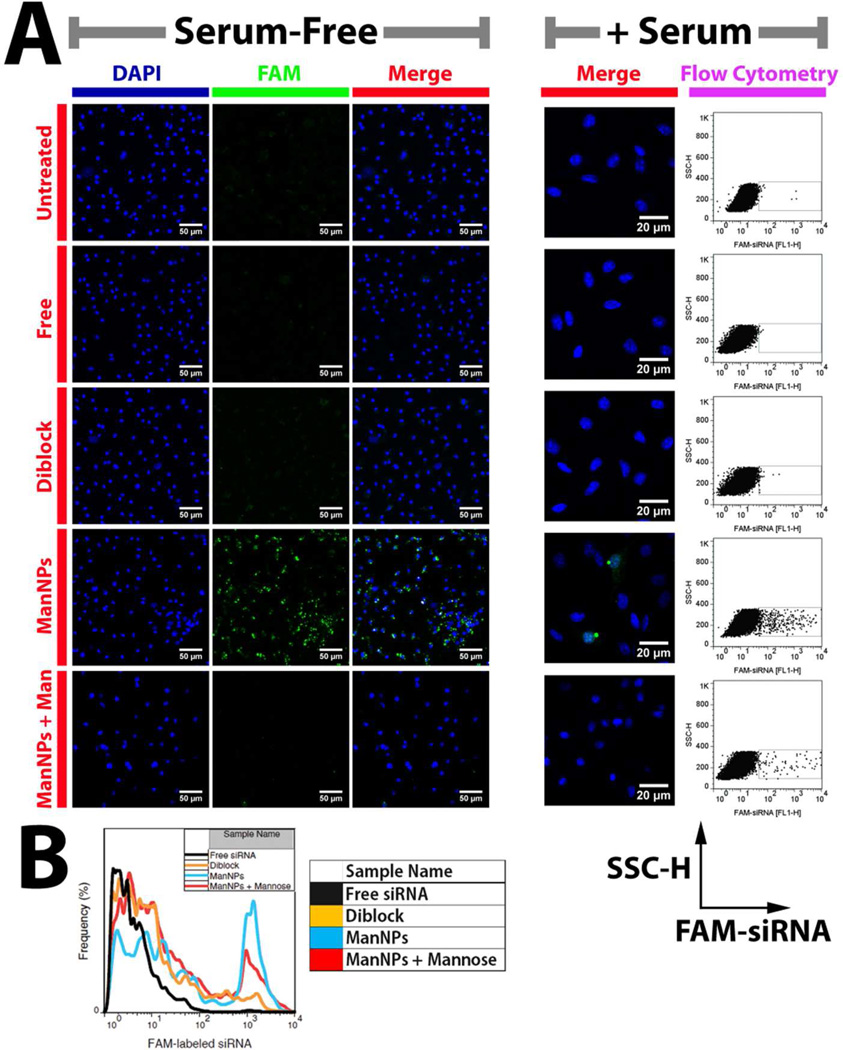

FIGURE 4. CD206-dependent siRNA Delivery to Primary Macrophages using ManNPs.

(A) Following 4h of transfection with FAM-siRNA (green; free or complexed into nanoparticles), BMDMs were fixed, nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), and imaged via confocal microscopy. (Scale bars = 50 µm for Serum-free; 20 µm for + Serum). Mannosylation of the polymeric vehicles enhanced their internalization by BMDMs. This could be competitively inhibited through co-administration of the ManNPs with D-mannose. A similar trend was observed when transfections were performed under serum conditions. FAM brightness and contrast were enhanced equally for all samples within the ‘+ Serum’ condition, but unaltered for the ‘Serum-Free’ condition. For the ‘Serum-free condition’, brightness & contrast were also enhanced in the DAPI channel to account for small differences in staining between samples. (B) Flow cytometry quantification of FAM-siRNA delivery into BMDMs via ManNPs (blue) relative to untargeted nanoparticles (orange) or free siRNA without vehicle (black) within 4 h of administration under serum-free conditions. Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity in each treatment group is in Supplementary Figure S6.

In support of these observations, imaging of the uptake of fluorescently-labeled siRNA into BMDMs was accomplished by confocal microscopy (Figures 4A, 5, Supplementary Figure S7). Consistent with the flow cytometry results, mannose targeting significantly increased siRNA delivery into macrophages, and co-administration of D-mannose with the ManNPs reduced FAM-siRNA signal in the BMDMs. Significant levels of FAM-siRNA can be visualized in the BMDMs within 1–2 h of administration.

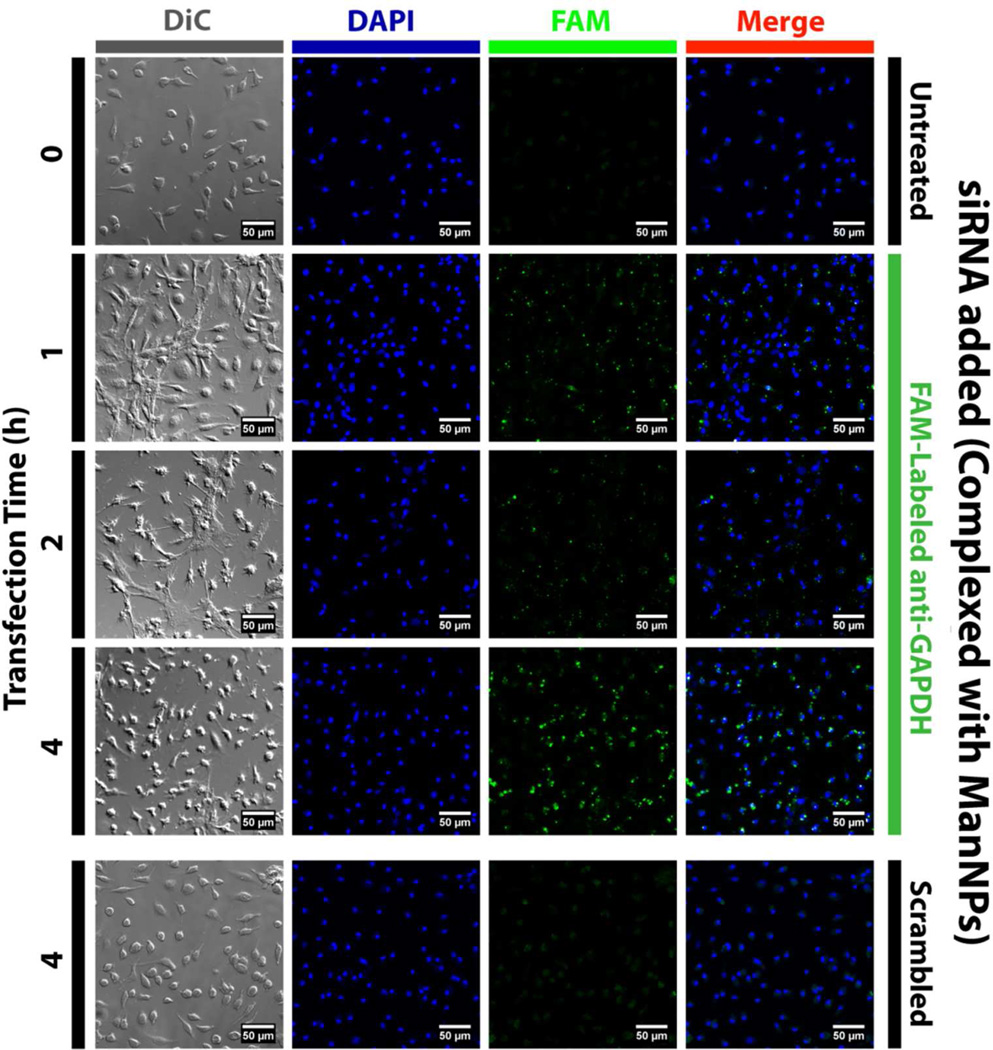

FIGURE 5. Kinetics of ManNP-Mediated siRNA Delivery into Primary Macrophages.

BMDMs were transfected with FAM-siRNA (green; complexed into ManNPs) for 1–4 h prior to being fixed, stained with DAPI (blue), and imaged via confocal microscopy. (Scale bars = 50 µm). As a comparison, BMDMs treated with non-fluorescent, scrambled siRNA (also complexed into ManNPs) are also shown. Brightness & contrast were enhanced in the DAPI channel to account for small differences in staining between samples. All settings were identical for FAM imaging. Punctate green signal is observed within 1–2 h of administration, suggesting internalization of siRNA into vesicles. At 4h, more green fluorescence has accumulated and the staining pattern is more diffuse, consistent with endosomal escape of the siRNA into the cytosol.

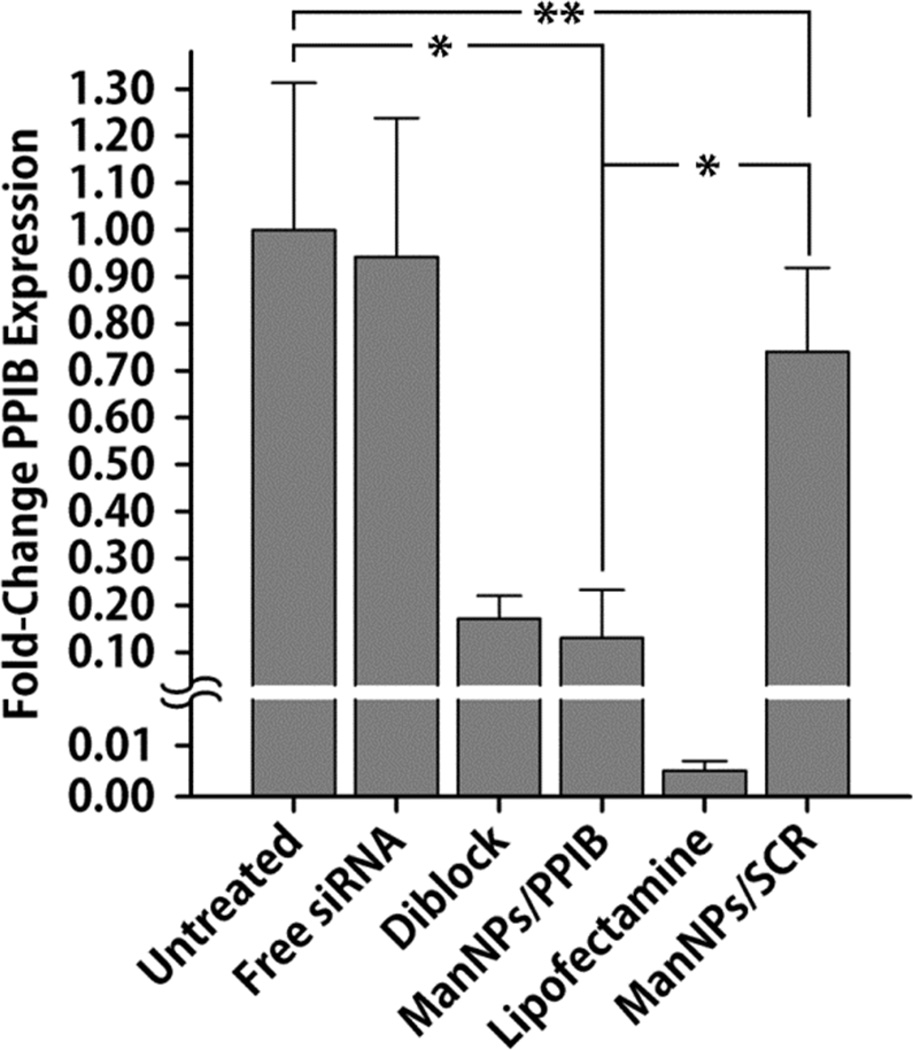

The enhanced delivery of siRNA via the ManNPs also corresponded with knockdown in expression of a model gene (PPIB; cyclophilin-B) in BMDMs relative to non-transfected cells and cells treated with complexes of ManNPs with scrambled siRNA (ManNPs/SCR; Figure 6; *p < 0.05). The commercially-available Lipofectamine RNAiMAX® transfection reagent was a reliable positive control, and was the most effective vehicle at facilitating the knockdown of PPIB expression (0.5 ± 0.2% residual PPIB expression). In spite of lower levels of siRNA delivery into the BMDMs relative to ManNPs (Figure 4), the diblock nanoparticles also facilitated a significant level of PPIB knockdown (p = 0.55 relative to ManNPs, via one-way ANOVA).

FIGURE 6. ManNPs Mediate Knockdown of PPIB Expression in BMDMs.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of PPIB expression using different transfection vehicles relative to controls. qRT-PCR confirmed ManNPs carrying anti-PPIB siRNA (ManNPs/PPIB) mediated 87 ± 10% decrease in target gene expression following 24 h of treatment, relative to non-transfected (NT) cells. Data was normalized to expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH as an internal control. Error bars represent standard deviation of 3 independent experiments (*p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA; **Not statistically significant). Some BMDMs were also transfected with ManNPs carrying scrambled siRNA (ManNPs/SCR) as an additional negative control.

DISCUSSION

Due to their central role in promoting the progression of a number of debilitating diseases, such as cancer and atherosclerosis, macrophages represent an important target for immunotherapy.19, 38 Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery is an attractive way to achieve this goal, because macrophages are phagocytes capable of efficiently internalizing particulate substances.39, 40 However, macrophages play functional roles in maintaining healthy physiology of many tissues, including bone, liver, and spleen.41–43 Therefore, to reduce the likelihood of off-target impact on healthy immune function, it is very important to specifically target macrophages at desired pathological sites. In this work, we demonstrated the design, synthesis, and characterization of mannosylated micellar nanoparticles to target CD206 expression, which is upregulated in tumor-associated macrophages.23, 24, 44, 45 The creation of these nanoparticles centers around a generalizable platform that can be utilized for ‘clicking’ ligands to be displayed on the surfaces of siRNA-condensing, polymeric nanoparticles. We opted for this strategy, involving the highly-efficient Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction, otherwise known as azide-alkyne ‘click’ chemistry (Figure 1), because it provides the necessary orthogonal chemistry to enable the synthesis of the block copolymers for siRNA delivery, followed by site-selective functionalization of the nanocarrier coronas with the ligand of interest in a final step. The resulting ManNPs exhibited diameters of <40 nm (Figure 2), a size range which confers the additional advantage of exhibiting improved passive accumulation into tumors.39, 46

The presented approach extends previous work by Convertine et al. describing polymers for siRNA delivery applications, which exhibited broad, nonselective transfection activity driven by their cationic corona.20 The diblock copolymers tested in the current work were patterned after these polymers and provide a reliable benchmark against which the ManNPs can be reasonably compared.20, 47 To improve the cellular specificity of these carriers, variants have been recently developed that target folate receptor and CD22.32, 33 These polymers included a micelle core-forming terpolymer block, which confers pH-responsiveness to the final polymers. Due to the pKa of these monomers (DMAEMA – 7.5, PAA – 6.7),48, 49 at pH 7.4, approximately 50% of the amine groups on DMAEMA are protonated (NH+), and 50% of the carboxylic groups on PAA are deprotonated (COO−). Therefore, the terpolymer is approximately charge neutral at pH 7.4 when DMAEMA cations and PAA anions are present in relatively balanced quantities, leading to the insolubility of the terpolymer in water at this pH. When the terpolymer is paired with a hydrophilic block to form an amphiphilic diblock structure, the terpolymer block’s electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions enable it to self-assemble into a micelle core at pH 7.4.20, 27, 47 With decreasing pH, the PAA and DMAEMA become increasingly protonated, leading to a net cationic charge on this block that triggers micelle disassembly.20 The exposed terpolymer is hypothesized to disrupt endosomal and lysosomal membranes and ferry siRNA into the cytoplasm. The block copolymers described here behave in a fashion consistent with this hypothesis, as they exhibit pH-dependent hemolysis at pH ranges that mimic the acidic environments of late endosomes (Figure 2G).

These polymeric siRNA nanocarriers have cationic ζ-potential due to the presence of the poly(DMAEMA) block (blue in Figure 1), and previous observations by others suggest that such agents can exhibit charge-dependent cytotoxicity.14 Consistent with these reports, a moderate level of cytotoxicity at N:P ratios of > 4:1 was not surprising. To counter this, all polyplexes for subsequent experiments were prepared at N:P ratios for which negligible cytotoxicity was observed at 24 h treatment time (Figure 3A). Nevertheless, the tradeoff between cytotoxicity versus micelle/siRNA delivery is an interesting area for study in order to determine the optimal charge ratio for biological applications, and is a characteristic that has been investigated by others working with similar siRNA delivery systems. Because of negligible cytotoxicity at N:P = 4:1, many test agents have been optimized and evaluated at this charge ratio.20, 27, 37 When optimally formulated with siRNA, it is anticipated that the presented polymeric delivery system for preferential macrophage targeting can be safely leveraged to treat diseases, such as cancer, where infiltrating macrophages at pathologic sites exhibit upregulated CD206 expression.50

The ManNPs show cell selectivity, and the data suggest that in a tumor environment where cancer cells coexist with a significantly smaller population of macrophages, the ManNPs will enter macrophages markedly faster than the cancer cells (Figure 3B–C). While this increased internalization rate was also observed for the diblock copolymer micelles, the effect was enhanced for the mannosylated constructs.

The ManNPs also facilitated improved siRNA delivery into primary murine macrophages and generated robust knockdown of a model gene (Figures 4–6). The untargeted, diblock polymers also achieved potent gene knockdown despite delivering significantly lower amounts of siRNA into the macrophages. However, like the ManNPs, the diblock polymers are capable of efficiently escaping from the endosomal compartment in a pH-dependent manner, as modeled via the hemolysis assay (Figure 2G).29 Therefore, even if the diblock copolymers are not as efficiently internalized into BMDMs as are the ManNPs, the diblock copolymers still deliver sufficient siRNA to cause significant levels of gene knockdown. This effect can depend on the potency of the siRNA sequence itself, as different siRNA sequences against the same target gene can exhibit widely different abilities to recognize the targeted mRNA sequence for knockdown.51

These results are significant because primary macrophages possess highly degradative phagocytic, endosomal and lysosomal compartments, providing a formidable barrier to the cytosolic delivery of siRNA.13 Moreover, since the ManNPs are internalized via an endocytotic receptor, these data indicate that ManNPs successfully mediate escape from the endosomal pathway, through a mechanism that is likely mediated by the pH-responsive, endosomolytic behavior of the core-forming terpolymer block.20

CONCLUSIONS

This report demonstrates a novel nanocarrier design for selectively targeting CD206-positive macrophages. The ManNPs’ hydrodynamic radius was ~20 nm by DLS, which is appropriate for in vivo tumor biodistribution through the enhanced permeation and retention effect. This novel carrier has finely-tuned pH-dependent membrane disruptive behavior, to overcome the macrophage’s highly degradative phagosomal and endosomal compartments. Nanocarrier characteristics enable biologics to be delivered into the macrophage cytosol, and promote access of the payload to intracellular drug targets and processes. Importantly, this generalized azide-containing siRNA delivery platform also has potential for click functionalization with alternative targeting ligands, and this is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of a ‘clickable’, pH-responsive, endosomolytic micelle for siRNA delivery. These strategies will potentially open up new areas in cancer immunotherapy, enabling selective intervention with siRNA therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported through a Concept Award through the Department of Defense CDMRP Breast Cancer Research Program (#W81XWH-10-1-0684). Bone marrow-derived macrophages were supported through a multi-investigator, collaborative IDEA Award through the Department of Defense CDMRP Breast Cancer Research Program (#W81XWH-11-1-0344 & #W81XWH-11-1-0242). Polymer development was also supported in part through NIH R21 EB012750. CML acknowledges partial support through a fellowship from the Vanderbilt Undergraduate Summer Research Program (VUSRP). Portions of this work were performed at the Vanderbilt Institute of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, using facilities renovated under NSF ARI-R2 DMR-0963361. Confocal microscopy was supported in part by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA068485, utilizing the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Shared Resource. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Shared Resource is also supported by NIH grants DK020593, DK058404, HD015052, DK059637 and EY08126. qRTPCR was performed in the laboratory of Prof. David G. Harrison (Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center). The authors also acknowledge Ryan A. Ortega (Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University) for reading and editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AzEMA

2-azidoethyl methacrylate

- BMA

butyl methacrylate

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophage

- CD206

macrophage mannose receptor

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DMAEMA

2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate

- FAM-siRNA

FAM-labeled anti-GAPDH siRNA

- ManNPs

mannosylated triblock copolymer nanoparticles

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- N:P:

charge ratio (NH+:PO4−)

- PAA

2-propylacrylic acid

- PPIB

Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase B (cyclophilin B)

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real time PCR

- RAFT

reverse addition-fragmentation chain transfer

- TAM

tumor-associated macrophage

- THP-1

immortalized human leukemic monocytes/macrophages

Footnotes

Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions SSY oversaw all materials design and synthesis, experimental design, and data collection, analysis and interpretation, with extensive input from FEY, CLD, and TDG. CML collected, analyzed, and interpreted data. WJO and HMO designed and selected the biological models used in this study, and assisted in biological experiments with SSY and CML, under the oversight of FEY. CEN and HL helped design protocols for the synthesis and purification of polymeric products, and contributed new reagents and analytic tools crucial to the experiments shown. SSY wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kindt TJ, Goldsby RA, Osborne BA, Kuby J. Kuby immunology. 6th ed. W.H. Freeman; New York: 2007. p xxii, 574, A-31, G-12, AN-27, I-27 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):605–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dirkx AE, Oude Egbrink MG, Wagstaff J, Griffioen AW. Monocyte/macrophage infiltration in tumors: modulators of angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(6):1183–1196. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0905495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasievich EA, Huang L. The Suppressive Tumor Microenvironment: A Challenge in Cancer Immunotherapy. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2011;8(3):635–641. doi: 10.1021/mp1004228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391(6669):806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Locati M. Macrophage Diversity and Polarization in Atherosclerosis: A Question of Balance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(10):1419–1423. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porta C, Rimoldi M, Raes G, Brys L, Ghezzi P, Di Liberto D, Dieli F, Ghisletti S, Natoli G, De Baetselier P, Mantovani A, Sica A. Tolerance and M2 (alternative) macrophage polarization are related processes orchestrated by p50 nuclear factor kappaB. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(35):14978–14983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809784106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagemann T, Lawrence T, McNeish I, Charles KA, Kulbe H, Thompson RG, Robinson SC, Balkwill FR. "Re-educating" tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-kappaB. J Exp Med. 2008;205(6):1261–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(5):1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kortylewski M, Swiderski P, Herrmann A, Wang L, Kowolik C, Kujawski M, Lee H, Scuto A, Liu Y, Yang C, Deng J, Soifer HS, Raubitschek A, Forman S, Rossi JJ, Pardoll DM, Jove R, Yu H. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(10):925–932. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leuschner F, Dutta P, Gorbatov R, Novobrantseva TI, Donahoe JS, Courties G, Lee KM, Kim JI, Markmann JF, Marinelli B, Panizzi P, Lee WW, Iwamoto Y, Milstein S, Epstein-Barash H, Cantley W, Wong J, Cortez-Retamozo V, Newton A, Love K, Libby P, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK, Koteliansky V, Langer R, Weissleder R, Anderson DG, Nahrendorf M. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29(11):1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aouadi M, Tesz GJ, Nicoloro SM, Wang M, Chouinard M, Soto E, Ostroff GR, Czech MP. Orally delivered siRNA targeting macrophage Map4k4 suppresses systemic inflammation. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1180–1184. doi: 10.1038/nature07774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stacey KJ, Ross IL, Hume DA. Electroporation and DNA-dependent cell death in murine macrophages. Immunol Cell Biol. 1993;71(2):75–85. doi: 10.1038/icb.1993.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv H, Zhang S, Wang B, Cui S, Yan J. Toxicity of cationic lipids and cationic polymers in gene delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;114(1):100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins SK, Egilmez NK, Suttles J, Stout RD. IL-12 rapidly alters the functional profile of tumor-associated and tumor-infiltrating macrophages in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178(3):1357–1362. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briley-Saebo KC, Cho YS, Shaw PX, Ryu SK, Mani V, Dickson S, Izadmehr E, Green S, Fayad ZA, Tsimikas S. Targeted Iron Oxide Particles for In Vivo Magnetic Resonance Detection of Atherosclerotic Lesions With Antibodies Directed to Oxidation-Specific Epitopes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(3):337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipinski MJ, Amirbekian V, Frias JC, Aguinaldo JG, Mani V, Briley-Saebo KC, Fuster V, Fallon JT, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. MRI to detect atherosclerosis with gadolinium-containing immunomicelles targeting the macrophage scavenger receptor. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(3):601–610. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cormode DP, Skajaa T, van Schooneveld MM, Koole R, Jarzyna P, Lobatto ME, Calcagno C, Barazza A, Gordon RE, Zanzonico P, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJ. Nanocrystal core high-density lipoproteins: a multimodality contrast agent platform. Nano Lett. 2008;8(11):3715–3723. doi: 10.1021/nl801958b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu SS, Ortega RA, Reagan BW, McPherson JA, Sung H-J, Giorgio TD. Emerging applications of nanotechnology for the diagnosis and management of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2011;3(6):620–646. doi: 10.1002/wnan.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Convertine AJ, Benoit DS, Duvall CL, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. Development of a novel endosomolytic diblock copolymer for siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2009;133(3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyer C, Bulmus V, Davis TP, Ladmiral V, Liu J, Perrier S. Bioapplications of RAFT polymerization. Chem Rev. 2009;109(11):5402–5436. doi: 10.1021/cr9001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolb HC, Sharpless KB. The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8(24):1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allavena P, Chieppa M, Bianchi G, Solinas G, Fabbri M, Laskarin G, Mantovani A. Engagement of the Mannose Receptor by Tumoral Mucins Activates an Immune Suppressive Phenotype in Human Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/547179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor PR, Gordon S, Martinez-Pomares L. The mannose receptor: linking homeostasis and immunity through sugar recognition. Trends in Immunology. 2005;26(2):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.East L, Isacke CM. The mannose receptor family. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2002;1572(2–3):364–386. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(5):1065–1073. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson CE, Gupta MK, Adolph EJ, Shannon JM, Guelcher SA, Duvall CL. Sustained local delivery of siRNA from an injectable scaffold. Biomaterials. 2012;33(4):1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirkland-York S, Zhang Y, Smith AE, York AW, Huang F, McCormick CL. Tailored design of Au nanoparticle-siRNA carriers utilizing reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymers. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(4):1052–1059. doi: 10.1021/bm100020x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans BC, Nelson CE, Yu SS, Kim AJ, Li H, Nelson HM, Giorgio TD, Duvall CL. Ex Vivo Red Blood Cell Hemolysis Assay for the Evaluation of pH-responsive Endosomolytic Agents for Cytosolic Delivery of Biomacromolecular Drugs. J Vis Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/50166. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connelly L, Jacobs AT, Palacios-Callender M, Moncada S, Hobbs AJ. Macrophage endothelial nitric-oxide synthase autoregulates cellular activation and pro-inflammatory protein expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(29):26480–26487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duvall CL, Convertine AJ, Benoit DS, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. Intracellular Delivery of a Proapoptotic Peptide via Conjugation to a RAFT Synthesized Endosomolytic Polymer. Mol Pharm. 2010;7(2):468–476. doi: 10.1021/mp9002267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benoit DSW, Srinivasan S, Shubin AD, Stayton PS. Synthesis of Folate-Functionalized RAFT Polymers for Targeted siRNA Delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(7):2708–2714. doi: 10.1021/bm200485b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palanca-Wessels MC, Convertine AJ, Cutler-Strom R, Booth GC, Lee F, Berguig GY, Stayton PS, Press OW. Anti-CD22 antibody targeting of pH-responsive micelles enhances small interfering RNA delivery and gene silencing in lymphoma cells. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19(8):1529–1537. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crownover E, Duvall CL, Convertine A, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. RAFTsynthesized graft copolymers that enhance pH-dependent membrane destabilization and protein circulation times. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2011;155(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumerlin BS, Tsarevsky NV, Louche G, Lee RY, Matyjaszewski K. Highly Efficient “Click” Functionalization of Poly(3-azidopropyl methacrylate) Prepared by ATRP. Macromolecules. 2005;38(18):7540–7545. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plotz PH, Rifai A. Stable, Soluble, Model Immune-Complexes Made with a Versatile Multivalent Affinity-Labeling Antigen. Biochemistry. 1982;21(2):301–308. doi: 10.1021/bi00531a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benoit DSW, Henry SM, Shubin AD, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. pH-Responsive Polymeric siRNA Carriers Sensitize Multidrug Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells to Doxorubicin via Knockdown of Polo-like Kinase 1. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2010;7(2):442–455. doi: 10.1021/mp9002255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollard JW. Macrophages define the invasive microenvironment in breast cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84(3):623–630. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu SS, Lau CM, Thomas SN, Jerome WG, Maron DJ, Dickerson JH, Hubbell JA, Giorgio TD. Size-and charge-dependent non-specific uptake of PEGylated nanoparticles by macrophages. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2012;7:799–813. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S28531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daldrup-Link HE, Golovko D, Ruffel B, DeNardo D, Castaneda R, Ansari C, Rao J, Tikhomirov GA, Wendland MF, Corot C, Coussens LM. MR Imaging of Tumor Associated Macrophages with Clinically-Applicable Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin P. Wound Healing--Aiming for Perfect Skin Regeneration. Science. 1997;276(5309):75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouwens L, Baekeland M, de Zanger R, Wisse E. Quantitation, tissue distribution and proliferation kinetics of kupffer cells in normal rat liver. Hepatology. 1986;6(4):718–722. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Felix R, Cecchini MG, Hofstetter W, Elford PR, Stutzer A, Fleisch H. Rapid publication: Impairment of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production and lack of resident bone marrow macrophages in the osteopetrotic op/op Mouse. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1990;5(7):781–789. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linehan SA, Martinez-Pomares L, Gordon S. Mannose receptor and scavenger receptor: two macrophage pattern recognition receptors with diverse functions in tissue homeostasis and host defense. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2000;479:1–14. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46831-X_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stahl PD, Ezekowitz RAB. The mannose receptor is a pattern recognition receptor involved in host defense. Current Opinion in Immunology. 1998;10(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen EK, Nielsen T, Wittenborn T, Birkedal H, Vorup-Jensen T, Jakobsen MH, Ostergaard L, Horsman MR, Besenbacher F, Howard KA, Kjems J. Size-Dependent Accumulation of PEGylated Silane-Coated Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Murine Tumors. ACS Nano. 2009 doi: 10.1021/nn900330m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Convertine AJ, Diab C, Prieve M, Paschal A, Hoffman AS, Johnson PH, Stayton PS. pH-Responsive Polymeric Micelle Carriers for siRNA Drugs. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(11):2904–2911. doi: 10.1021/bm100652w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van de Wetering P, Moret EE, Schuurmans-Nieuwenbroek NM, van Steenbergen MJ, Hennink WE. Structure-activity relationships of water-soluble cationic methacrylate/methacrylamide polymers for nonviral gene delivery. Bioconjugate chemistry. 1999;10(4):589–597. doi: 10.1021/bc980148w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grainger SJ, El-Sayed MEH. Stimuli-Sensitive Particles for Drug Delivery. In: Jabbari E, Khademhosseini A, editors. Biologically-Responsive Hybrid Biomaterials. Singapore: World Scientific; 2010. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo Y, Zhou H, Krueger J, Kaplan C, Lee S-H, Dolman C, Markowitz D, Wu W, Liu C, Reisfeld RA, Xiang R. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages as a novel strategy against breast cancer. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(8):2132–2141. doi: 10.1172/JCI27648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rettig GR, Behlke MA. Progress toward in vivo use of siRNAs-II. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2012;20(3):483–512. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.