Abstract

Hematopoiesis—the process that generates distinct lineage-committed blood cells from a single multipotent hematopoietic stem cell—is a complex process of cellular differentiation regulated by a set of dynamic transcriptional programs. Cytokines and growth factors, transcription factors, chromatin remodeling, and modifying enzymes have been suggested to enact critical roles during hematopoiesis, leading to the development of myeloid, lymphoid, erythroid and platelet precursors. How is such a complex process orchestrated? Is there a higher order of hematopoiesis regulation? These are some of the unresolved questions in the field of hematopoiesis. Here, we suggest that cohesin, which is known to mediate chromosomal cohesion between sister chromatids, may have a central role in the orchestration of hematopoiesis and serve as a master transcriptional regulator.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are competent to reconstitute the entire repertoire of blood cells. How the HSCs originate in the body is unclear, although it is generally accepted that mesodermal cells in the early embryo are induced to produce these multipotent cells [1]. HSCs undergo both self-renewal and hematopoietic differentiation (hematopoiesis) continuously throughout the lifespan of an individual [2]. The enormity of the hematopoietic program can be well appreciated from the following two numbers: 3.5 × 1011, the number of blood cells produced each day in an adult human [3], and 0.7 to 1.5, the mean number of HSCs per 108 nucleated bone marrow cells in an adult human [4]. Importantly, at least under normal circumstances, blood cells are not produced in excess, indicating that there are stringent mechanisms regulating hematopoiesis. Impairment of these mechanisms results in defective differentiation and/or uncontrolled production of specific blood cells, a process that can result in leukemogenesis (see [5] for a review). Understanding the biology of hematopoietic stem cells, as well as hematopoiesis in general, is necessary for improved treatments of hematologic malignancies, congenital disorders, chemotherapy-related cytopenias, and reconstitution after stem cell transplantation. Here we attempt to underscore the enormity and complexity of molecular processes that dictate hematopoiesis. Specifically, we will discuss how the chromosomal cohesin complex can act as a master regulator of transcription and chromatin reconfiguration in orchestrating hematopoiesis at a global level.

Hematopoiesis: an overview

Classically, hematopoiesis was thought to be comprised of the following cell compartments: (1) self-renewable hyper-proliferative cells that differentiate into (2) multipotent cells with limited proliferative capacity, which further differentiate into (3) mature blood cells [6]. During the last half a century, finer details have emerged delineating the potency and hierarchy of hematopoietic cell types [2,7,8]. HSCs are the undifferentiated precursors to all blood cell types, and are the starting point of hematopoietic differentiation. The HSCs have the ability to self-renew and to differentiate into progenitor cells that further differentiate into multiple cell types (Fig. 1). It is unclear how this process occurs, and how the cell decides whether to self-renew or to differentiate into one of the progenitors. One theory is that cell-fate determination is a stochastic process. The intrinsic genetic and epigenetic make up of the HSC, as well as cues from the external environment, determine a cell’s fate “by chance” to decide a path [6,7,9]. The differentiation of HSCs involves multiple steps that have been extensively reviewed ([2,8,10–13]; see illustration in Fig. 1). According to one of the accepted models [12], HSCs differentiate into two types of multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs): the megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor, which gives rise to the erythroid lineage, and the lymphomyeloid bipotent progenitor, which generates the lymphoid and myeloid lineages. The lymphomyeloid bipotent progenitor diversifies into the common lymphoid progenitors that generate B cells and natural killer cells; the early thymic progenitor differentiates into the T-cell lineages, and the granulocyte-macrophage progenitor that gives rise to myeloid cells.

Figure 1.

A schematic of hematopoietic differentiation. The solid curved arrow represents higher potential of self-renewal of LT-HSCs. This schematic merges several models as discussed in references 2, 8, 10–13. LT-HSC=Long-term HSC; ST-HSC=short-term HSC; CMP=common myeloid progenitor; LMPP=lymphoid-primed MPP; ETP=early T-lineage progenitor; MEP=megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor; GMP=granulocyte-monocyte progenitor; CLP=common lymphoid progenitor; Ery=erythrocyte; Mka=megakaryocyte; Gra=granulocyte; Mac= macrophage; Neu=neutrophil; Eos=eosinophil; Den=dendritic cell; B=B-cells; T=T-cells; NK=natural killer cells.

Till and colleagues [6] expanded on a “birth and death” model of hematopoietic differentiation, where the HSC renews itself (birth) or loses its identity by differentiating into a different cell type (death). Irrespective of what turns on either birth or death signals in the otherwise quiescent HSCs, it is conceivable that both the birth and death processes involve significant alterations in the epigenome and transcriptome. Because the overall proteome of a cell at a given time confers the cell’s identity, the representative cells at each step during hematopoietic differentiation are expected to differ in their overall transcriptional signature.

The path of differentiation is normally unidirectional; that is, a cell loses the ability to regain multipotency once committed to the process of differentiation. This notion presupposes that genes essential to the identity of the differentiated cell should not be expressed in the stem or progenitor cell. In this context, it can be noted that leukemia was once considered a disease of proliferation at particular stages during hematopoiesis, and distinct leukemic cells were expected to maintain the gene expression signature typical of the cell types from which they were derived. However, several studies reported expression of multilineage gene signatures in leukemic cells, and these genes were interpreted as misregulated in these leukemias [14]. Interestingly, similar multilineage gene expression signatures were subsequently observed in multipotent progenitors [15], which reportedly occur before unilineage commitment [16]. It is now established that MPPs exhibit cross-lineage signatures of gene expression, and the same is true for the HSCs as well [17,18]. In recent studies, numerous enhancer elements in both the lymphoid and myeloid genes are found to be activated in progenitor cells by virtue of underlying histone H3 lysine monomethylation at position 4 (H3K4me1) [19]. Thus, the HSCs and multipotent progenitors express several genes related to multiple lineages, and several lineage-specific genes undergo repression during the process of differentiation. Such dynamics reveals two important aspects of transcriptional complexity: first, openness to multilineage gene signatures in the HSCs, and second, gradual restriction to unilineage gene signatures during differentiation.

The first requisite of an HSC being conducive to the process of differentiation is considered entering a state of “priming,” where the chromatin allows expression of genes related to multiple lineage specifications. Next, there is a progressive repression of genes related to undesired lineages, representing a gradual acquisition of “plasticity” in lineage choices. Two independent groups uncovered a major mechanism by which pluripotent stem cells prime genes for expression. Developmental genes in stem cells are marked with both protranscriptional (H3K4me3 and H3K9ac) and repressive (H3K27me3) histone modifications (called “bivalent” chromatin domains) to keep them poised for transcription [20,21]. Two distinct levels of priming can be envisaged in the context of stem cell differentiation. Creating a transcription-conducive chromatin architecture ready to respond to stimuli forms the first level of priming (molecular/transcriptional priming), while the resultant cross-lineage transcriptome primes the cell as a whole to respond to prospective lineage choices (cellular priming). This discussion reveals that the path from an HSC to a differentiated blood cell is extremely complex and involves multiple levels of transcription regulation. At the molecular level, hematopoiesis (or any path of differentiation) is characterized by a succession of changes in gene expression patterns. That is, an intricate balance of dynamic transcriptional activation and repression of key hematopoietic genes define a particular stage of hematopoiesis. Alterations in existing gene expression patterns can be achieved by asymmetrical cell division, where the resulting daughter cells differ in the pool of transcripts and proteins [22], or by the cell’s microenvionment (niche) that exposes the cell to transcriptional stimulants [23]. Thus, a cell experiences gradual suppression of a set of genes and simultaneous activation of other key genes during hematopoiesis. Indeed, extensive gene expression profiling experiments during hematopoiesis carried out over the past decade support this notion [17,24]. The key genes that show such dynamic alterations in expression are usually the ones that code for transcription factors (TFs). For instance, the majority of the HOX genes are preferentially expressed in the HSCs with moderate expression in progenitors, whereas they are repressed during downstream hematopoietic differentiation [25]. Therefore, the entire transcriptional programs can be considered to be centered on TFs. Consistent with this notion, review of the existing literature reveals a TF-centric picture of hematopoiesis, where specific TFs drive specific hematopoietic programs [26–29].

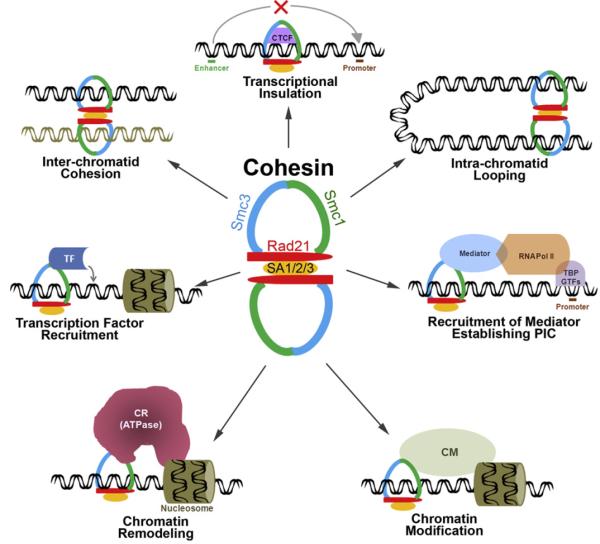

In addition to the sequence-specific TFs, the eukaryotic transcription regulation is a result of extensive interplay among numerous players including basal transcription machinery (comprised of the general transcription factors and the RNA polymerase), the mediator complex, chromatin modifiers and remodelers, co-activators, co-repressors, and effector molecules [30]. How such numerous players collaborate to ultimately establish a specific gene expression signature of a cell is not fully understood. It is conceivable that there may be master regulators that play key roles in conducting transcription by communicating with all known classes of factors that influence gene expression. We propose that cohesin, the ring-like protein complex responsible for chromosomal cohesion, is one such potential candidate that can function as a master regulator orchestrating the repertoire of complex gene expression programs in hematopoiesis. As discussed below, and as depicted in Figure 2, cohesin not only reportedly interacts with sequence-specific TFs, RNA polymerase II and the associated components including the mediator, and chromatin remodelers and modifiers, but also mediates chromatin looping to facilitate both transcription activation and repression.

Figure 2.

Cohesin as a master-regulator of transcription and chromatin reconfiguration. Apart from ensuring sister chromatid cohesion, cohesin cooperates with CTCF to effectuate transcriptional insulation, forms looping of chromatin to bring enhancers and promoters closer, recruits the mediator complex to support establishment of the pre-initiation complex (PIC), interacts with and recruits tissue- and signal-specific TFs, and interacts with chromatin remodeling (CR) and chromatin modifying (CM) enzymes to possibly recruit these activities to the promoter to support transcription.

Cohesin as a conductor of transcription and chromatin reconfiguration

DNA replication in S-phase produces two identical copies of the chromosomal DNA, called sister chromatids. The sister chromatids are held together until the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, when they are set apart to segregate to opposite poles. Holding the sister chromatids together, or cohesion, is accomplished by the cohesin ring [31,32]. Cohesin is composed of a tripartite ring formed with Smc1, Smc3, and Rad21, along with one of the stromal antigen proteins SA1 or SA2 (see Table 1). Based on the molecular associations of cohesin subunits, we have recently provided evidence for a handcuff model of the cohesin complex, which consists of two rings [33]. Each ring has a set of Rad21, Smc1, and Smc3 molecules. The handcuff is established when two Rad21 molecules in the cohesins move into anti-parallel orientation that is enforced by either SA1 or SA2. In this model, each sister chromatid is entrapped by a ring, and cohesion is completed when two rings join to form the handcuff. Cohesin is a multiprotein complex that not only comprises of four core subunits (Smc1, Smc3, Rad21, and SA1/2), but also a number of associated proteins that support cohesin function (see Table 1). The cohesin cycle includes loading of cohesin onto chromatin, establishment of cohesion between two sister chromatids, cohesion maintenance, cohesin unloading, and dissolution. In higher eukaryotes, the majority of cohesins are removed from chromosome arms in early prophase in a process that requires the kinase PLK1, phosphorylation of SA2 and the cohesin-associated protein WAPAL and PDS5 [31,32]. Work in our laboratory recently proposed that the cohesin-associated protein Sororin coordinates PLK1’s mediation of chromosomal arm separation [34]. Additionally, we have demonstrated that calcium-inducible cleavage of Rad21 by Calpain-1 also promotes chromosomal arm separation [35]. The residual cohesins from the centromeres are removed at the onset of anaphase by a Separase-mediated cleavage of Rad21, culminating in separation of the sisters [36].

Table 1.

Cohesin and cohesin-associated proteins in humans

| Cohesin structural units | Rad21, Smc1, Smc3, SA1 (STAG1)/SA2 (STAG2) |

|---|---|

| Cohesin associated proteins with a role in: | |

| Cohesin loading: | Nipbl, Scc4 |

| Cohesion establishment: | Esco1, Esco2 |

| Cohesin maintenance: | Pds5A, Pds5b, Wapl, Sororin |

| Cohesin dissolution: | Separase, Securin, Sororin, Shugoshin, Plk1, Calpain-1 |

Apart from its canonical role in sister chromatid cohesion, cohesin has been implicated in a number of cellular processes, including hematopoiesis, apoptosis, DNA damage response, replication, transcription regulation, and centrosome function [31,37]. While some of these functions still rely on the “cohesive” function of cohesin (e.g., DNA damage response, DNA replication), transcription regulation by cohesin stands out as its “noncohesive” function. In recent years, regulation of transcription by cohesin has unambiguously established itself as a new field of research [37]. The initial clues to cohesin’s involvement in gene regulation came from works on Nipped-B, which is required for transcription of select genes in Drosophila [38]; its human counterpart NIPBL was later identified as a cohesin-loader [39]. Reduced level of Drosophila Nipped-B affects transcription of select genes without affecting chromosome cohesion [37], while reduction in the level of either NIPBL or cohesin affects the expression of the same set of genes [40]. Several recent reports have demonstrated direct roles of cohesin in transcription regulation. Cohesin has been mapped to genomic loci along with RNA polymerase II in Drosophila [41], as well as to transcriptionally active loci along with the boundary element regulator CTCF in human [42] and mouse [43] cells. Cohesin also directly regulates transcription of the c-Myc gene in zebrafish, a phenomenon that is evolutionarily conserved [44].

A critical necessity in the regulation of transcription is the task of bringing distant enhancers and basal promoters together, or to block such communications altogether (Fig. 2). Along with CTCF, cohesin organizes the looping of chromatin to bring enhancers and promoters to close proximity [45–47], as well as to ensure gene repression by blocking the enhancer-promoter communication [48,49]. Cohesin also coordinates transcription independently of CTCF and in collaboration with tissue-specific TFs [50], indicating that cohesin may play a direct role in TF recruitment. Cohesin also physically interacts with the mediator complex and mediates looping between the enhancer and the promoter [51]. Recently, cohesin has been demonstrated to selectively bind to and regulate genes with paused RNA polymerase [52]. These observations argue for cohesin as a potent regulator of transcription [53].

Importantly, cohesin’s potential as a highly promising “master regulator” or “conductor” of transcription is demonstrated by its interactions with chromatin remodeling and modification machinery. Cohesin forms a functional multiprotein complex along with the human chromatin remodelers SNF2h and NuRD, and preferentially associates with Alu-rich sequences enriched with certain histone modifications [54]. Cohesin has also been reported to function in collaboration with two budding yeast chromatin remodelers RSC [55,56] and Ino80 [57], and has been identified as an epigenetic silencing factor, along with DNA methyl transferase DNMT3A and histone deacetylase HDAC1 [58]. Interestingly, the cohesin component RAD21 was identified in Drosophila as a trithorax-group protein [59], further suggesting that it is an epigenetic regulator. Recently, we have identified chromatin remodeler CHD4, the histone methyl transferase SETD3, linker histone H1 and its chaperone NAP1L1 as specific interactors of cohesin [60].

This model (see Fig. 2) portrays cohesin as a transcription regulator that organizes chromatin domains that are conducive or inhibitory to transcription, thereby mediating both activation and repression of transcription; interacts with several tissue-specific TFs, demonstrating its flexibility as a potent transcription regulator; co-occupies chromatin loci with RNA polymerase and also physically interacts with chromatin, TF, mediator complex (an essential component of the core transcription machinery); and interacts with (possibly recruits) both chromatin remodeling and modifying complexes. All these qualities are vital and, in our opinion, adequate, to consider cohesin as a “master regulator” of transcription.

Role of cohesin in hematopoiesis

Although this discussion presents a promising picture of cohesin as a master regulator of transcription, cohesin’s involvement in hematopoiesis or hematologic malignancies argue for its important regulatory role in hematopoietic differentiation. A number of recent studies have described the role of cohesin and cohesin-associated-proteins affecting hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies. Haploinsufficiency in Rad21 causes impaired clonogenic regeneration of the bone marrow stem cells [61] and cohesin components Rad21 and Smc3 were reported in a zebrafish model to regulate the expression of the hematopoietic regulator Runx1. In this model loss of cohesin RAD21 represses RUNX1, and the bone marrow cells fail to develop differentiated blood cells [62]. In mouse bone marrow depletion of the cohesion-resolving protease Separase results in death of all nonerythroid cells and in severe bone marrow aplasia within 3 days [63]. Cohesin and cohesin-linked proteins have also been implicated in leukemia. Abnormally high level of Separase expression has been reported for chronic myeloid leukemia blast crisis and chronic phase cells [64]. We have reported higher Separase enzymatic activity in several leukemia-derived cell lines (acute myeloid leukemia) and leukemia patient samples [65]. Recently, we have reported in a murine model that reduced Separase function cooperates with p53 to cause aggressive lymphoma and leukemia with an early latency [66]. Interestingly, cohesin component genes RAD21 and STAG2/SA2 have been found to be deleted in leukemia patient samples [67], while non-TCR chromosome translocations t(3;11)(q25;p13) and t(X;11)(q25;p13) activating LMO2 by juxtaposition with MBNL1 and SA2 in leukemia have also been reported [68]. Interestingly, the cohesin-associated protein PDS5A has recently been identified as a new fusion partner of MLL [69]. In these cases, it is not clear whether the cohesive or noncohesive function (or both) of cohesin is impaired. However, recurring mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients have recently been identified in the genes encoding all four components of the cohesin complex [70]. Interestingly, 18 of the 19 such acute myeloid leukemia genomes did not exhibit aneuploidy, suggesting impairment of the noncohesive function of cohesin in leukemia. Additionally, in an attempt to characterize the cohesin-interactome, we have recently identified YBX1, the hematopoietic transcription factor, as a specific interactor of cohesin [60]. Collectively, these findings highlight the strong involvement of cohesin and cohesin-associated proteins in hematopoietic differentiation.

Conclusions

Cohesin has recently emerged as a new regulator of transcription and it communicates with sequence-specific TFs and basal transcription machinery, mediates architectural chromatin organization, and communicates with chromatin remodeling and modification molecules. The role of cohesin has not been adequately investigated in any particular system of cellular differentiation. However, based on the available data, we propose cohesin as a potential master regulator of hematopoietic transcriptional programs, playing a central role in the higher-order orchestration of hematopoiesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Margaret Goodell and Terzah Horton for critically reading the manuscript.

Funding disclosure This study was supported by grants awarded to D. Pati from the National Cancer Institute (1RO1 CA109478).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure No financial interest/relationships with financial interest relating to the topic of this article have been declared.

References

- 1.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis and stem cells: plasticity versus developmental heterogeneity. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:323–328. doi: 10.1038/ni0402-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:640–653. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaziri H, Dragowska W, Allsopp RC, Thomas TE, Harley CB, Lansdorp PM. Evidence for a mitotic clock in human hematopoietic stem cells: loss of telomeric DNA with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9857–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abkowitz JL, Catlin SN, McCallie MT, Guttorp P. Evidence that the number of hematopoietic stem cells per animal is conserved in mammals. Blood. 2002;100:2665–2667. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown G, Hughes PJ, Ceredig R, Michell RH. Versatility and nuances of the architecture of haematopoiesis—Implications for the nature of leukaemia. Leuk Res. 2012;36:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Till JE, McCulloch EA, Siminovitch L. A stochastic model of stem cell proliferation, based on the growth of spleen colony-forming cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;51:29–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingli D, Pacheco JM. Modeling the architecture and dynamics of hematopoiesis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:235–244. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceredig R, Rolink AG, Brown G. Models of haematopoiesis: seeing the wood for the trees. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:293–300. doi: 10.1038/nri2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abkowitz JL, Catlin SN, Guttorp P. Evidence that hematopoiesis may be a stochastic process in vivo. Nat Med. 1996;2:190–197. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo M. Lymphoid and myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Immunol Rev. 2010;238:37–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murre C. Developmental trajectories in early hematopoiesis. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2366–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.1861709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida T, Ng SY, Georgopoulos K. Awakening lineage potential by Ikaros-mediated transcriptional priming. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Determinants of lymphoid-myeloid lineage diversification. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:705–738. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCulloch EA. Stem cells in normal and leukemic hemopoiesis (Henry Stratton Lecture, 1982) Blood. 1983;62:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greaves MF, Chan LC, Furley AJ, Watt SM, Molgaard HV. Lineage promiscuity in hemopoietic differentiation and leukemia. Blood. 1986;67:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu M, Krause D, Greaves M, et al. Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Genes Dev. 1997;11:774–785. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akashi K, He X, Chen J, et al. Transcriptional accessibility for genes of multiple tissues and hematopoietic lineages is hierarchically controlled during early hematopoiesis. Blood. 2003;101:383–389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyamoto T, Iwasaki H, Reizis B, et al. Myeloid or lymphoid promiscuity as a critical step in hematopoietic lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2002;3:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercer EM, Lin YC, Benner C, et al. Multilineage priming of enhancer repertoires precedes commitment to the B and myeloid cell lineages in hematopoietic progenitors. Immunity. 2011;35:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, et al. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:532–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiner SL, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Division of labor with a workforce of one: challenges in specifying effector and memory T cell fate. Science. 2007;317:622–625. doi: 10.1126/science.1143775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang LD, Wagers AJ. Dynamic niches in the origination and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:643–655. doi: 10.1038/nrm3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kluger Y, Lian Z, Zhang X, Newburger PE, Weissman SM. A panorama of lineage-specific transcription in hematopoiesis. Bioessays. 2004;26:1276–1287. doi: 10.1002/bies.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Argiropoulos B, Humphries RK. Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6766–6776. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engel I, Murre C. Transcription factors in hematopoiesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:575–579. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dias S, Xu W, McGregor S, Kee B. Transcriptional regulation of lymphocyte development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dore LC, Crispino JD. Transcription factor networks in erythroid cell and megakaryocyte development. Blood. 2011;118:231–239. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-285981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swiers G, Patient R, Loose M. Genetic regulatory networks programming hematopoietic stem cells and erythroid lineage specification. Dev Biol. 2006;294:525–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters JM, Tedeschi A, Schmitz J. The cohesin complex and its roles in chromosome biology. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3089–3114. doi: 10.1101/gad.1724308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onn I, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Guacci V, Unal E, Koshland DE. Sister chromatid cohesion: a simple concept with a complex reality. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:105–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang N, Kuznetsov SG, Sharan SK, Li K, Rao PH, Pati D. A handcuff model for the cohesin complex. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1019–1031. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang N, Panigrahi AK, Mao Q, Pati D. interaction of sororin with polo-like kinase 1 mediates the resolution of chromosomal arm cohesion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41826–41837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panigrahi AK, Zhang N, Mao Q, Pati D. Calpain-1 cleaves Rad21 to promote sister chromatid separation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4335–4347. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06075-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauf S, Waizenegger IC, Peters JM. Cohesin cleavage by separase required for anaphase and cytokinesis in human cells. Science. 2001;293:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1061376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorsett D. Cohesin: genomic insights into controlling gene transcription and development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rollins RA, Morcillo P, Dorsett D. Nipped-B, a Drosophila homologue of chromosomal adherins, participates in activation by remote enhancers in the cut and Ultrabithorax genes. Genetics. 1999;152:577–593. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonkin ET, Wang TJ, Lisgo S, Bamshad MJ, Strachan T. NIPBL, encoding a homolog of fungal Scc2-type sister chromatid cohesion proteins and fly Nipped-B, is mutated in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:636–641. doi: 10.1038/ng1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaaf CA, Misulovin Z, Sahota G, et al. Regulation of the Drosophila Enhancer of split and invected-engrailed gene complexes by sister chromatid cohesion proteins. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misulovin Z, Schwartz YB, Li XY, et al. Association of cohesin and Nipped-B with transcriptionally active regions of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Chromosoma. 2008;117:89–102. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, et al. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature. 2008;451:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature06634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell. 2008;132:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhodes JM, Bentley FK, Print CG, et al. Positive regulation of c-Myc by cohesin is direct, and evolutionarily conserved. Dev Biol. 2010;344:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hadjur S, Williams LM, Ryan NK, et al. Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus. Nature. 2009;460:410–413. doi: 10.1038/nature08079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hou C, Dale R, Dean A. Cell type specificity of chromatin organization mediated by CTCF and cohesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3651–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majumder P, Boss JM. Cohesin regulates MHC class II genes through interactions with MHC class II insulators. J Immunol. 2011;187:4236–4244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mishiro T, Ishihara K, Hino S, et al. Architectural roles of multiple chromatin insulators at the human apolipoprotein gene cluster. EMBO J. 2009;28:1234–1245. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nativio R, Wendt KS, Ito Y, et al. Cohesin is required for higher-order chromatin conformation at the imprinted IGF2-H19 locus. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt D, Schwalie PC, Ross-Innes CS, et al. A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription. Genome Res. 2010;20:578–588. doi: 10.1101/gr.100479.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fay A, Misulovin Z, Li J, et al. Cohesin selectively binds and regulates genes with paused RNA polymerase. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1624–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhodes JM, McEwan M, Horsfield JA. Gene regulation by cohesin in cancer: is The Ring An Unexpected Party to proliferation? Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1587–1607. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hakimi MA, Bochar DA, Schmiesing JA, et al. A chromatin remodelling complex that loads cohesin onto human chromosomes. Nature. 2002;418:994–998. doi: 10.1038/nature01024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang J, Laurent BC. A Role for the RSC chromatin remodeler in regulating cohesion of sister chromatid arms. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:973–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baetz KK, Krogan NJ, Emili A, Greenblatt J, Hieter P. The ctf1330/CTF13 genomic haploinsufficiency modifier screen identifies the yeast chromatin remodeling complex RSC, which is required for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1232–1244. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1232-1244.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogiwara H, Enomoto T, Seki M. The INO80 chromatin remodeling complex functions in sister chromatid cohesion. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1090–1095. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.9.4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poleshko A, Einarson MB, Shalginskikh N, et al. Identification of a functional network of human epigenetic silencing factors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:422–433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hallson G, Syrzycka M, Beck SA, et al. The Drosophila cohesin subunit Rad21 is a trithorax group (trxG) protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12405–12410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801698105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panigrahi AK, Zhang N, Otta SK, Pati D. A Cohesin-RAD21 Interactome. Biochem J. 2012;442:661–670. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu H, Balakrishnan K, Malaterre J, et al. Rad21-cohesin haploinsufficiency impedes DNA repair and enhances gastrointestinal radiosensitivity in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Horsfield JA, Anagnostou SH, Hu JK, et al. Cohesin-dependent regulation of Runx genes. Development. 2007;134:2639–2649. doi: 10.1242/dev.002485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wirth KG, Wutz G, Kudo NR, et al. Separase: a universal trigger for sister chromatid disjunction but not chromosome cycle progression. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:847–860. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel H, Gordon MY. Abnormal centrosome-centriole cycle in chronic myeloid leukaemia? Br J Haematol. 2009;146:408–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basu D, Zhang N, Panigrahi AK, Horton TM, Pati D. Development and validation of a fluorogenic assay to measure separase enzyme activity. Anal Biochem. 2009;392:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mukherjee M, Ge G, Zhang N, et al. Separase loss of function cooperates with the loss of p53 in the initiation and progression of T- and B-cell lymphoma, leukemia and aneuploidy in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rocquain J, Gelsi-Boyer V, Adelaide J, et al. Alteration of cohesin genes in myeloid diseases. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:717–719. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen S, Nagel S, Schneider B, et al. Novel non-TCR chromosome translocations t(3;11)(q25;p13) and t(X;11)(q25;p13) activating LMO2 by juxtaposition with MBNL1 and STAG2. Leukemia. 2011;25:1632–1635. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Put N, Van Roosbroeck K, Broek IV, Michaux L, Vandenberghe P. PDS5A, a novel translocation partner of MLL in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2011;9:1587–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150:264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]