Abstract

In signed languages, the arguments of verbs can be marked by a system of verbal modification that has been termed “agreement” (more neutrally, “directionality”). Fundamental issues regarding directionality remain unresolved and the phenomenon has characteristics that call into question its analysis as agreement. We conclude that directionality marks person in American Sign Language, and the ways person marking interacts with syntactic phenomena are largely analogous to morpho-syntactic properties of familiar agreement systems. Overall, signed languages provide a crucial test for how gestural and linguistic mechanisms can jointly contribute to the satisfaction of fundamental aspects of linguistic structure.

1. Introduction

Spoken languages display multiple devices for making clear the relationships between verbs and their arguments, including discourse patterns, word order, case morphology on nouns, and ‘person marking’, which can include agreement morphology on verbs as well as (possibly weak or clitic) pronouns (Siewierska 2004). Languages vary in their use of these devices. English mainly relies on word order, while case and verb agreement are vestigial. In typical Romance languages such as Spanish, rich systems of subject-verb agreement allow relatively flexible word order and null arguments. In topic-prominent languages such as Mandarin, word order allows the overt arguments of a verb to be identified, and default patterns of discourse interpretation contribute to the identification of a verb’s null arguments despite the absence of agreement morphology.

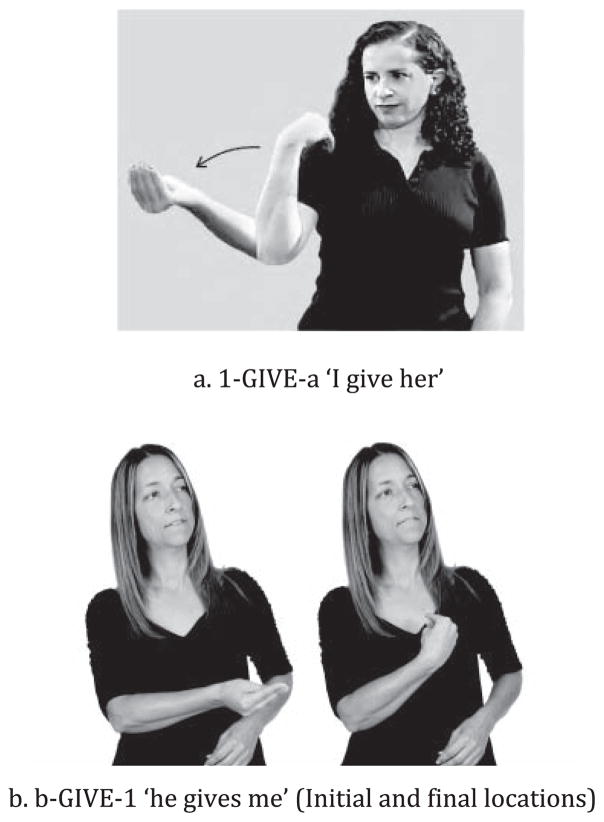

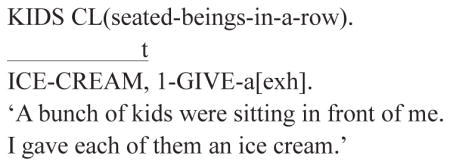

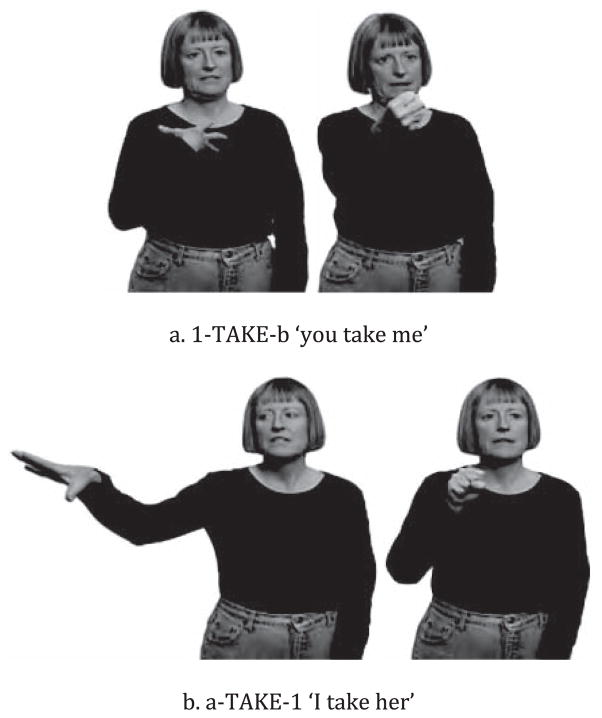

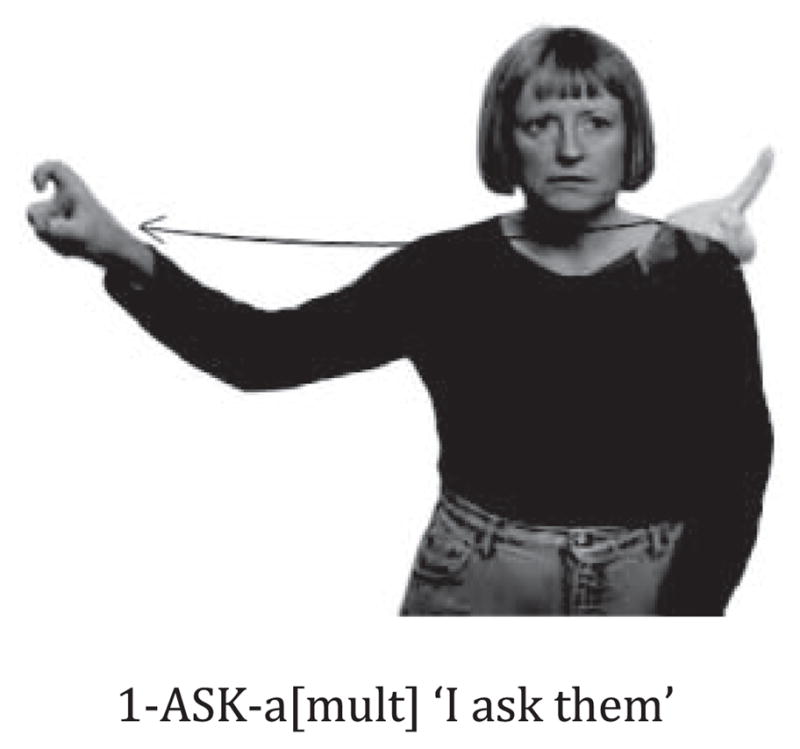

In signed languages, the arguments of verbs are identified by word order, by discourse interpretation patterns for null arguments like those of Mandarin, and/or by a system of verbal modification that has been termed “agreement” (see Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006 for an overview). A label for this phenomenon that is neutral with respect to its proper grammatical analysis is “directionality” (Fischer & Gough 1978, Casey 2003a); verbs that participate in the system are directional verbs. As we will review, much thought has gone into the analysis of directionality in signed languages. To see why, consider a form such as 1-GIVE-a ‘I give her’ or b-GIVE-1 ‘he gives me’; as illustrated in Figure 1, these forms resemble gestural enactments of the actions of one person giving an object to another. But such verbs, however iconic, have also been treated as inflected forms that agree in person and number with subject and object. As we will discuss, fundamental issues remain unresolved in the analysis of these verb forms.

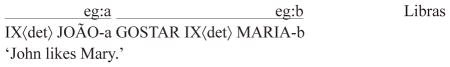

Figure 1.

Verb directionality

This paper describes the phenomenon of directionality, which is characterized primarily by the movement of verb signs between locations within the signing space. We then outline the agreement analysis, and review the arguments against an analysis in terms of agreement. A major concern about the agreement analysis pertains to the spatial locations with which verbs appear to agree. Scott Liddell (2000) argued that it is impossible to give a uniform morphophonological analysis of the spatial locations used in directional verbs. With this problem in mind, he concluded that directionality is not verb agreement; in fact, he argued, directionality is not linguistic, because it requires reference to things clearly outside of the language system. His analysis instead treats certain verbs as ‘indicating’ their arguments gesturally. On this view, there is no grammatical phenomenon of verb agreement in sign languages at all.

We suggest that it is profitable to approach this debate from a slightly different viewpoint than has been adopted in the past. Rather than asking only whether the phenomenon under discussion is properly considered agreement, we will ask whether it is appropriate to consider directionality to be a kind of person marking. Siewierska (2004) identifies several different types of person marking across the world’s languages, characterizing them according to whether they may or may not co-occur with a local or non-local controller. On her classification, whether the form itself is independent or dependent (affix or clitic) is not the crucial issue. When we conclude, as we will, that directionality marks person in American Sign Language, we will be able to conclude that directional verbs are marked for at least a subset of the phi-features that are generally associated with agreement in spoken languages (namely, person and number). Furthermore, we will show that the ways person marking interacts with syntactic phenomena are analogous to the morpho-syntactic properties of familiar agreement systems.

This revised view is discussed in the light of two types of arguments which have been raised against the agreement analysis. One set of arguments concerns aspects of directionality that lead some researchers (including Liddell) to conclude that it is non-linguistic and gestural. This view is considered in Section 4, and arguments against it are provided. There we support the view that person marking exists as a grammatical phenomenon in sign languages. Our claim is that the challenges to an agreement analysis raised in this section can be addressed by re-considering the interface between language and gesture, which we discuss in Section 5.

The second set of arguments accept the phenomenon as linguistic, but challenge its analysis as agreement in the sense familiar from the study of European languages. We outline these concerns in Section 6, and discuss them within the person-marking viewpoint. Our goal in this section is to outline the points that any specific detailed analysis will need to account for; we do not intend to propose a full analysis here. In Section 7, we put forward additional arguments for an analysis involving person marking of the sort usually associated with agreement, showing that the morpho-syntactic effects of directionality provide support for an agreement analysis.

We will generally be discussing data from American Sign Language (ASL)1, but essentially similar systems are found in all mature sign languages that have been described in the literature. On occasion, we will present data from other sign languages, particularly when discussing the syntactic ramifications of directionality. Implications of the near-universality of directionality in sign languages will be discussed in Section 6.

The target article concludes with discussion of some unresolved issues. We note that – to the extent that the system proves to be gestural – then signed languages will provide a crucial test for how gestural and linguistic mechanisms can jointly contribute to the satisfaction of fundamental aspects of linguistic structure, such as the identification of a verb’s arguments and the tracking of referents within and across utterances.

2. The phenomenon

In order to describe the system of verb directionality in sign languages, we start with the use of locations in space to pick out individuals. Central issues in the analysis of agreement (such as the existence of person distinctions) are already apparent when considering the properties of independent pronouns, as described in section 2.1. In section 2.2 we provide a more detailed introduction to verb directionality, although many important characteristics of this phenomenon will only be discussed later, when we discuss the pros and cons of the agreement analysis.

2.1. Independent pronouns

In sign languages, locations are used for reference (Friedman 1975; Klima and Bellugi 1979). To begin, we take the simplest case and focus on what are typically analyzed as overt lexical pronouns, but many of the same comments will be made subsequently with reference to the locations used with verbs showing directionality.2

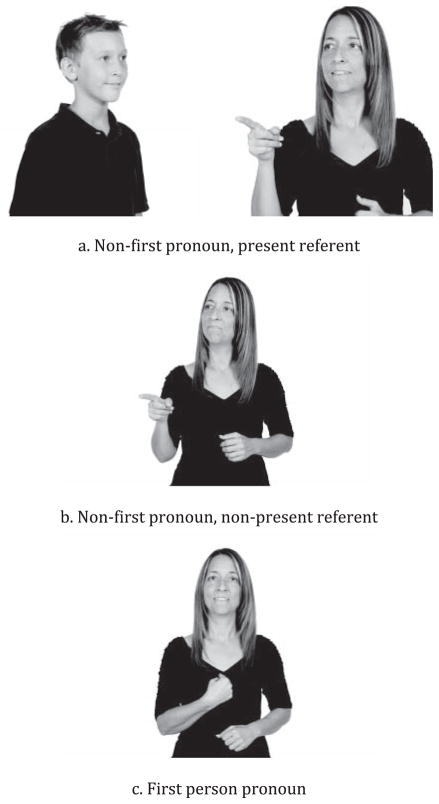

To refer to him- or herself, the ASL signer points to the center of his/her torso (see Figure 2c). Is this pointing sign, apparently the same as points to self used by non-signers, best analyzed as a gestural indication meaning “this one”? Or is it appropriately analyzed as a personal pronoun meaning “I” or “me” (as in Meier 1990)? We will argue below that the appropriate analysis is in terms of person.

Figure 2.

Linguistic pointing

For referents that are not first person, the space around a signer is used. For example, pointing toward a person actually located in the immediate physical context of a signed utterance can be analyzed as a deictic pronoun referring to that person (see Figure 2b). When a referent is not present in the immediate physical context of the conversation, signers will point toward an abstract location (see Figure 2c). This location is associated with its referent through various means (Padden 1983; Rinfret 2009), including linguistic statements (roughly, “(imagine) Carol is here on my right”). A point to such an abstract location can also be analyzed as a deictic pronoun, picking out the referent previously associated with that location. We adopt the term R(eferential)-loci for spatial locations used in this way.3 We distinguish the physical spatial locations toward which a signer points from the notion of a R(eferential)-index, an abstract grammatical device indicating reference within and across sentences.4

Already some curious properties of reference in sign languages can be detected. For example, there is a clear linguistic distinction between first and non-first pronouns, but not between second and third (Meier 1990). Engberg-Pedersen (1993) came to the same conclusion for Danish Sign Language, as did Smith (1990) for Taiwan Sign Language. Non-first pronominal forms always consist of a point to the location of their referent (or to a location assigned to that referent), whether that referent is an addressee or not. The non-first forms are entirely decomposable in this way. However, there are several ways in which the first person forms are different. Following are some of the arguments for distinctive first-person pronominal forms in signed languages; many of these were already noted by Meier (1990):

There are cross-linguistic differences in the form of first-person pronouns. For example, in Japanese Sign Language (JSL) and languages related to it (Japan Sign Language Research Institute 1997; Smith & Ting 1979), one variant of the first person pronoun contacts the nose, whereas the first person pronoun in most signed languages has contact at the center of the chest.5

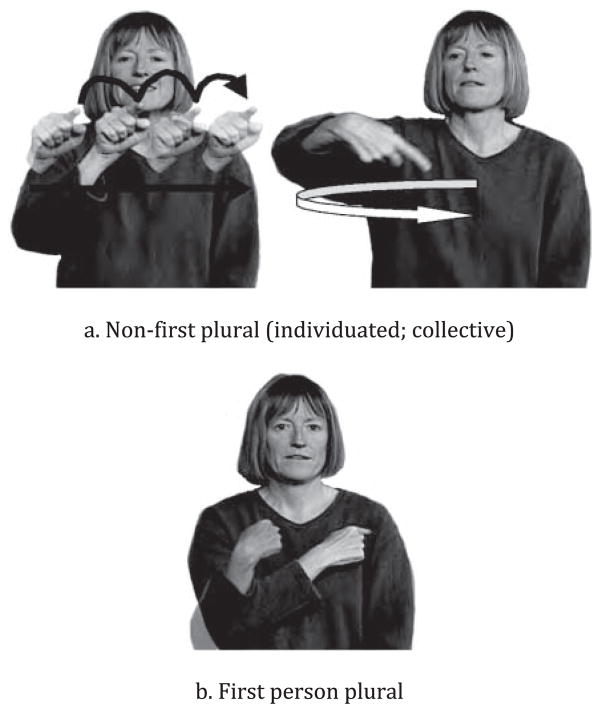

Non-first person plural forms are compositional. There are two variants used in ASL. One can be analyzed as the singular non-first person form plus an arc; the second as a series of non-first pronouns. On the other hand, there are idiosyncratic first-person plural pronoun forms (WE and OUR) that are not compositional products of first-person and plural morphemes.6 See Figure 3 for illustrations of these forms.

In direct quotation, a first person point contacting the center of the signer’s chest is interpreted as referring to the quoted signer, not to the actual signer. Non-first forms always pick out the referent pointed to. (Indirect quotation behaves like other kinds of embedding: pointing to the center of the signer’s chest is interpreted as referring to the current signer, not to the signer of whatever is being quoted.)

Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) has a distinctive B-hand possessive form that is restricted to first-person possessors; two other possessive pronouns can be used with all persons (Pizzio, Rezende & Quadros 2009).

Figure 3.

Plural pronouns

At this time, we know of no arguments for manual distinctions between second- and third-person signs (whether pronouns or, as we will see, agreeing verbs). The forms of pronouns picking out the addressee and non-addressed participants are identical; the only distinction is the discourse role played by the person so picked out. To date, arguments for a grammatical distinction between second- and third-person in signed languages have hinged on observations of the patterns of gaze to addressees versus non-addressed participants. For example, Berenz (2002) argues on the basis of data from Brazilian Sign Language that gaze, head, chest, and hand will typically align along the midline of the signer’s body in second-person forms, but that there will be a disjunction (typically with hand deviating from the midline while gaze continues at midline) in third-person forms (see also Alibašić Ciciliani and Wilbur 2006 on Croatian Sign Language). Berenz indicates that this contrast between second- and third-person forms is consistent in her data (although she provides no quantitative information).

To be conclusive, such arguments must demonstrate systematic differences in the signer’s eye gaze to an addressee, as a function of whether that addressee is being referred to or not. Since the signer is likely to gaze at the addressee throughout much of an interaction, it is important to demonstrate that gaze to the addressee accompanying reference to the addressee goes beyond what would be expected from baseline gaze behavior. Inasmuch as signers also look to spatial locations associated with non-addressed participants when they are referring to those non-addressed participants, comparisons of gaze to addressees versus non-addressed participants are needed.

We conducted a mini-study employing the measures suggested here, using a corpus of 24 minutes of conversation between a native Deaf signer and a fluent (but non-native) hearing signer, collected for a different purpose. Gaze produced during points to self (n = 35) was used as a rough estimate of baseline gaze direction, inasmuch as the signer cannot direct his own gaze to his own location. (Points produced during direct questions were excluded from analysis. Questioning constitutes an independent reason for gaze to addressee, as such gaze is often cited as one of the non-manual markers accompanying questions; e.g., Baker and Cokely 1980.) The results are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Gaze produced during points to self, addressee, and non-addressed referent (24-minute sample)

| Gaze

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressee | Non-addressed referent | Other | ||

|

| ||||

| Point | Self | 0.6 | 0.06 | 0.34 |

| Addressee | 0.67 | 0 | 0.33 | |

| Non-addressed referent | 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.06 | |

The results presented in Table I make it clear that at least for the mini-corpus used for this analysis, gaze to addressee during points to the addressee is not anywhere near 100% consistent, and in fact, not significantly above baseline gaze to addressee during points to self (p = .48, one-tailed exact binomial). Furthermore, the proportion of gaze to addressee does not differ for points to addressee versus points to non-addressed referents (p = .59, Fisher exact probability, one-tailed; total points to addressee were 9 and total points to non-addressed referents were 16.). These data indicate that gaze direction is not sufficient to differentiate points to addressee and points to non-addressed referents as a grammatical marking of second versus third person.

A stronger tendency for gaze to differ between points to addressee and points to non-addressed referents appears in a sample drawn from Auslan (Australian Sign Language). In a preliminary report based on 116 pointing forms from a large corpus, Johnston (2010) reported that points to addressee were accompanied by gaze at addressee approximately 90% of the time. Points to a non-addressed referent were accompanied by gaze to the addressee approximately 45% of the time, and by gaze to the target approximately 40% of the time (the remaining 15% of the time gaze is in some other unspecified direction). No baseline information from gaze during points to self or non-pointing signs is available. In Johnston’s Auslan corpus there is a stronger tendency for points to the addressee to be accompanied by gaze to the addressee than we found in our mini-study. However, the contrast expected by Berenz’ proposal between alignment during reference to addressee and disjunction during reference to non-addressees is not substantiated by the Auslan data. The large proportion of cases during which points to a non-addressed referent were accompanied by gaze to that referent (i.e., cases of ‘alignment’ with third-person referents) indicate that gaze is not a sufficient grammatical marker for distinguishing second and third person in Auslan.

Another puzzling property of reference in sign language pronouns is that multiple non-first referents can be unambiguously distinguished because pointing refers back to the specific R-locus associated with a specific referent (Lillo-Martin and Klima 1990). Thus, unlike person categories such as third singular in spoken languages, pronouns (and, as we will see, directional verbs) are not ambiguous – they pick out particular referents, not a class of referents (e.g., the class of male humans) from which an individual must be selected using pragmatic information. In example (1a), the pronoun (a-IX) picks out Mary by virtue of pointing to the location associated with her; similarly, in (1b), the pronoun (b-IX) picks out Sue.

-

(1)

-

a-MARY a-INFORM-b b-SUE a-IX PASS TEST.‘Maryi informed Suej that shei passed the test.’

-

a-MARY a-INFORM-b b-SUE b-IX PASS TEST.‘Maryi informed Suej that shej passed the test.’

-

In context, of course, most spoken language pronouns are disambiguated (e.g., Grosz et al. 1995), just as signed pronouns are only understood as picking out a particular referent when the context has established how a particular locus is to be understood. However, the explicitness of the connection between a pronoun and its referent even in a particular discourse is quite different between signed and spoken languages.

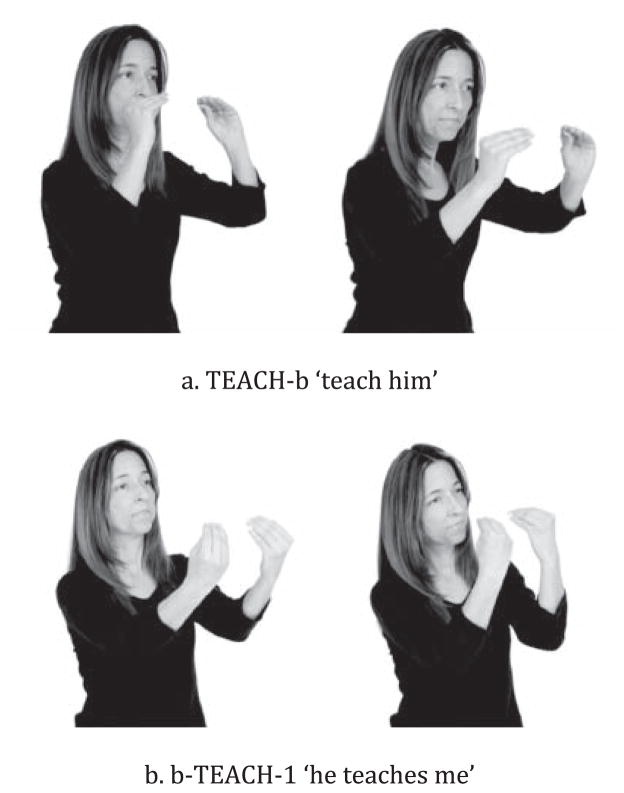

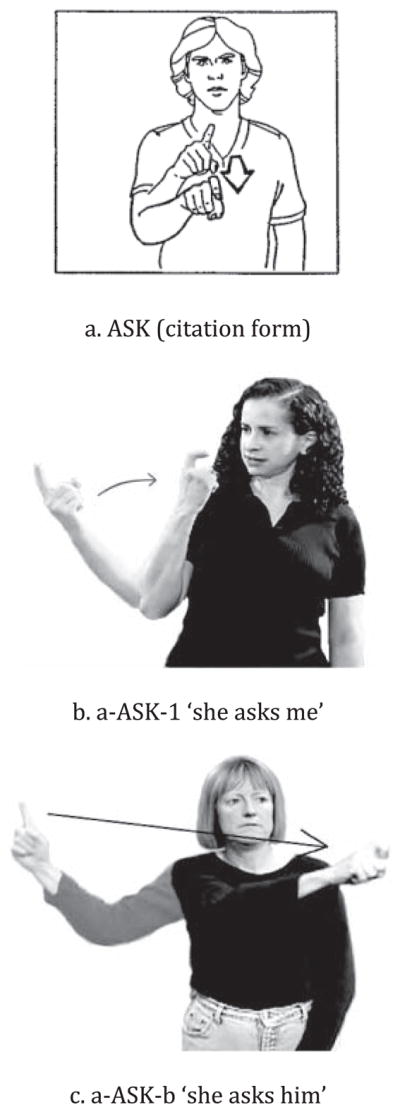

2.2. Directional verbs

Many of the linguistic properties of independent pronouns in ASL also manifest themselves in directional verbs, inasmuch as the R-loci used in the pro nominal system also form the basis for this linguistic phenomenon. Some verbs will (sometimes) change their movement trajectory and/or facing of the hand so that the verb starts at the R-locus associated with the subject of the verb and ends directed at the R-locus associated with its object (Fischer and Gough 1978; Meir 1998; Padden 1983) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Verb directionality (person)

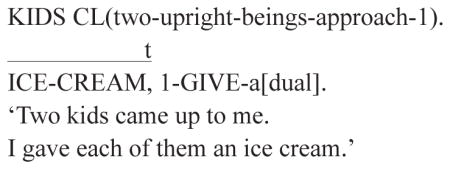

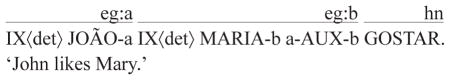

In almost all signed languages described to date (see Section 6.2 for discussion of exceptions), at least three verb classes have been identified. The first class contains verbs which show directionality to indicate a human subject/object, such as GIVE, HELP, and ASK. These verbs, often referred to as simply (person) agreeing verbs, are claimed to show agreement in person (first vs. non-first) and number with subject and object. To show number, the signs are modified in the number of loci used; for example, one type of plural marking in directional verbs, as in pronouns, employs the addition of an arc movement (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Directionality with plural marking

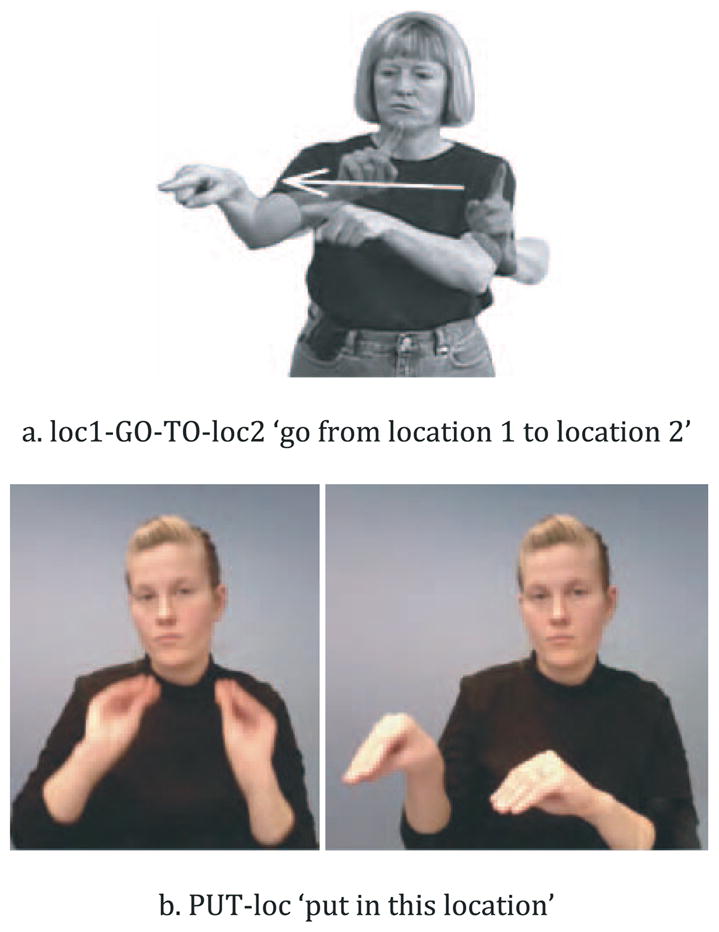

The second class contains spatial verbs, sometimes called location agreeing verbs. These verbs, such as PUT, MOVE, and GO-TO, move with respect to locations associated with locative arguments/adjuncts of those verbs. Some of these verbs move between two loci, indicating movement from a source to a goal (see Figure 6a). Others are signed in a particular locus that indicates the location or endpoint/goal of an event (see Figure 6b).7

Figure 6.

Verb directionality (location)

The third class contains plain verbs, such as EAT, KNOW, LOVE, and LIKE, which are generally non-directional (see Figure 7a). Although this class of verbs is considered non-agreeing, some of them can actually be signed in a locus associated with a location of an event (e.g. WANT, BUY, and LEAVEALONE) (see Figures 7b and 7c).

Figure 7.

Plain verbs

There has been considerable discussion in the literature about the classification of verbs in these three categories (see, e.g., Quadros and Quer 2008). However, at least descriptively, the vast majority of known sign languages display the basic properties of directionality as just described. There are some cross-linguistic differences in the categorization of verbs for specific concepts, though even that is strikingly near-uniform (see Meir 1998). The field of sign linguistics has come to the point that it would be surprising to come across (established) sign languages without this type of verbal system (cf. Newport and Supalla 2000).

3. Agreement-like characteristics

In what way is directionality as just described analyzable as verb agreement? To answer this question, let us consider the prototypical case of agreement and see how directionality measures up.

Agreement can be analyzed as the sharing of features between a ‘controller’ and a ‘target’ (Corbett 2006). According to Barlow & Ferguson (1998: 1), under agreement “a grammatical element X matches a grammatical element Y in property Z within some grammatical configuration.” In spoken languages, a subject noun phrase might be marked as first-person singular or third-person plural due to lexical choices (e.g., pronouns) or morphological marking (e.g., plurality). If a verb agrees with its subject, the form of the verb changes (for example, it might appear with a particular affix) depending on the features of the subject.

Directionality can be considered as a similar sort of feature sharing (Cormier et al. 1998; Aronoff et al. 2005). The verb’s argument (subject/object/locative) is the ‘controller’; the shared features include person (expressed through an R-locus) and number. Under such a view, agreement is seen as “structure-sharing of the index value of one expression with the index value of another expression” (Cormier et al. 1998: 222). However, as Aronoff et al. (2005: 316) point out, agreement morphology is the expression of these shared index values, “but mediated by the partly arbitrary referential and classificatory morphosyntactic categories of the individual language.” Thus, the morphosyntactic idiosyncrasies of sign language verb agreement (such as verb classification) might be seen as expected under the normal range of cross-linguistic variation.

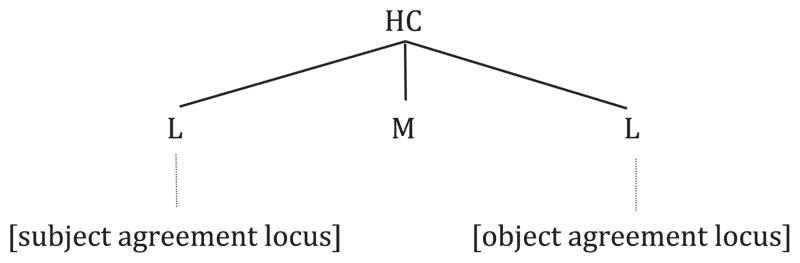

What is the morphological form of agreement under such feature-sharing approaches? Often directionality has been described as a sort of holistic change in the movement path. However, since Liddell (1984) and Sandler (1989), it has been clear that agreement should be described with reference to the linear structure of verbs. Under Sandler’s approach, signs are segmented according to locations (L) and movements (M), with the typical sign having the structure LML (a starting location, with movement to an ending location); the hand configuration (HC) spreads across all three segments. Using a templatic approach to morphology, the lexical representation of a (doubly) agreeing verb, such as GIVE, would not be specified for certain features of its initial and final location segments. These features are filled in through the agreement process. This analysis is schematized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Verb agreement template (Sandler 1989)

The ‘agreement’ analysis has been the standard view of directional verbs in the sign literature for three decades (e.g. Fischer and Gough 1978; Padden 1983; Janis 1995; Meir 1998), despite the acknowledgment of challenges and occasional alternative linguistic analyses (e.g. Fischer 1975; Kegl 2003). However, since about 1990 it has been seriously challenged by an alternative, non-linguistic analysis, which has gained prominence.

4. Challenge to the agreement analysis –The linguistic treatment of spatial loci

Several properties of the phenomenon we are calling directionality have raised doubts about its status as verb agreement. As we noted at the outset, a major concern has to do with the analysis of spatial loci as markers of agreement. In a series of articles, Liddell argued that it is impossible to give a uniform morpho-phonological analysis of the R-loci used in directionality. With this problem in mind, Liddell (2000) concluded that directionality is not verb agreement; in fact, he argued, directionality is not even linguistic, because it requires reference to things clearly outside of the language system. His alternative analysis treats certain verbs as ‘indicating’ their arguments gesturally. On his view, there is no grammatical phenomenon of verb agreement in sign languages at all.

In the following sub-sections, we review this challenge to the agreement analysis of directional verbs, focusing for the moment on issues concerning subject/object (person) marking rather than spatial (location) marking. We acknowledge that a number of Liddell’s observations are important considerations for any analysis of directional verbs. However, we reject any conclusion that directionality is entirely non-linguistic. As we go over the arguments made by Liddell and by others, we will point out that despite these concerns, directionality must at the very least be considered a linguistic process of person marking.

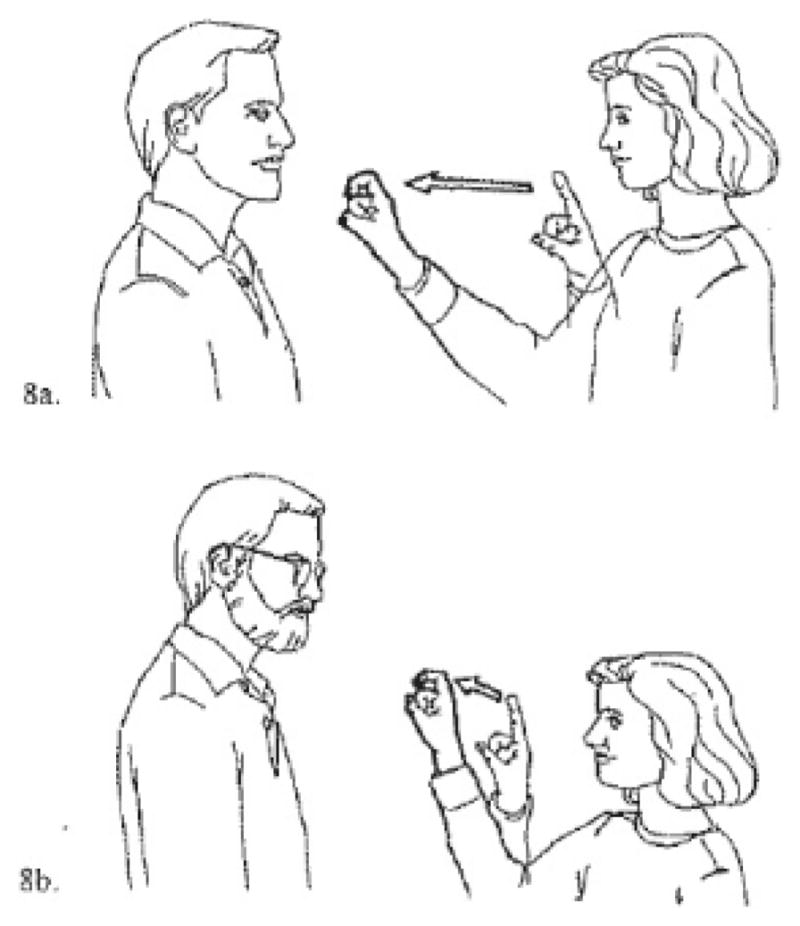

4.1. Present/real-world referents and surrogates

Liddell (1990, 1994, 1995, 2000, 2003) points out that the loci used for pronouns and for agreement are often tied to either actual or imagined real-world locations. To illustrate the complexity of this situation, consider the fact that verbs may be lexically specified for height within the sign space. Such specifications are part of the phonological information about the verb, though they may be partially motivated on the basis of the verb’s meaning. We will refer to the verb’s specified height as its y value, as in coordinate geometry. For example, the sign ASK begins at the chin height of the asker and is directed toward the chin height of the person being asked. Thus, when the sign is marked for agreement with a present referent whose height is approximately equal to that of the signer, the verb sign moves along a horizontal plane (see Figure 9a). However, Liddell pointed out that when such a verb is marked for agreement with a taller present referent, the verb sign moves upward toward the chin height of the person being asked (see Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

The sign ASK directed toward addressees of different heights (Liddell 1990: 182; reproduced by permission of Gallaudet University Press)

Signers adjust their signing space to accommodate the visual area of their addressees, so changes such as the one illustrated in Figure 9 might be seen as a part of a general raising of the signing space when addressing a taller referent. However, the adjustment exemplified in this figure can also take place when referring to a non-present referent in the presence of an addressee of a height similar to that of the signer. In other words, it is the relevant conceived height of the referent (present or not) that affects the sign’s y value.

The problem is this: if the description of the loci used in verb ‘agreement’ requires reference to the world (the current physical situation), are those loci really part of the linguistic system? If the loci are not linguistic, how can the process using them be? Liddell’s conclusion in his 2000 paper is that the loci are not linguistic, and that therefore there is no system of verb agreement. Instead, verbs indicate their arguments gesturally.8

Previously, researchers had used terms such as “establishing an index” to discuss the relationship between loci and referents. They might talk about a locus as standing for a referent. On Liddell’s view, the relation between a referent and a locus is not referential equality (Referenta = Locusa), but rather, it is location fixing (Referenta is at Locusa). Present referents are clearly understood as at a locus, their actual current physical locations. Non-present referents may be understood as fixed in a certain locus with either a full-size imagined projection (‘surrogate’), or a smaller-sized ‘token’ with some depth (to accommodate height differences between verbs).

If a locus is simply a location at which a referent is imagined, Liddell’s argument goes, then it is properly considered outside the grammar. Liddell takes the position that loci are simply locations, not part of the realization of some grammatical notion such as person, because of his reluctance to employ an abstract agreement morpheme whose exact form cannot be specified linguistically. In regard to the problem of analyzing loci, he says:

“Attempting a morphemic solution … would either require an unlimited number of location and direction morphemes or it would require postulating a single morpheme whose form was indeterminate.” (Liddell 1995: 24–25)

The implication is that linguists should refrain from postulating morphemes with indeterminate form. It is this latter point with which we disagree. As we discuss in more detail in Section 5, we agree that a locus cannot be understood as a geometric point; we also agree that the process which determines the physical locations used in reference must make direct connection with the gestural component of language. However, we do not exclude the possibility of postulating abstract morphemes with indeterminate form. Abstract grammatical morphemes are characteristic of many linguistic phenomena, such as reduplication. In such cases, a formal analysis of a linguistic process is possible through the use of templatic morphology – just as has been proposed for sign language agreement.

An example of abstract grammatical morphemes used in an agreement system is presented by Aronoff et al. (2005). In literal alliterative agreement, as found in languages such as Bainouk (Niger-Congo), agreement can take the form of copying phonological information from one element onto another. In Bainouk agreement on a determiner takes in certain cases the form of a copy of the initial CV of the noun stem. Although such agreement systems are rare, they have an important aspect in common with sign language verb directionality, by which the verb and its argument share elements of form.

Clearly, languages do use abstract grammatical morphemes for processes including person marking. Thus, although we accept Liddell’s points about the need to use aspects of gesture in explaining the form of directionality, we nonetheless maintain that directionality is a grammatical system for marking person.

4.2. What features are agreed with?

As described, the expression of verb agreement has to do with movement between loci in signing space. Do sign language verbs agree with their arguments in (traditional) φ-features, generally taken to include person, number, and gender?

The clearest case is number, as there are arguably identifiable morphemes distinguishing agreement with singular versus plural referents. Most descriptions include dual, multiple, and ‘exhaustive’ forms, as illustrated in (2); see also Figure 5 above.

-

(2)

Liddell (2003) discusses the plural forms of verbs, but rejects characterizing the process as number agreement. Rather, he sees marking of multiple referents on a verb as part of the same gestural indicating process that marks single referents. However, others have supported the idea that forms such as those described here constitute number marking (cf. Rathmann and Mathur 2002). McBurney (2002), discussing pronouns, specifically argues that the distinction between singular, dual, and plural shows grammatical number marking. Her arguments can also be applied to the case of number marking on verbs.

It has been claimed that some sign languages, particularly those in East Asia, also have identifiable morphemes for gender agreement (Fischer 1996). Our understanding of these gender morphemes is that they are used only to refer to non-present referents, that is, with referents that are not present in the immediate conversational context. We will not attempt to explore the consequences of such a restriction on the analysis of agreement here.

The most controversial question regarding φ-features has to do with person. As we reviewed earlier, Meier (1990) proposed that ASL distinguishes first person from non-first person in pronouns. The conclusion that ASL pronouns encode person distinctions does not force the issue for directional verbs; instead, directional verbs could simply move between spatial locations that are associated with referents. However, we argue that the same person distinctions which hold for pronouns also hold for directional verbs.

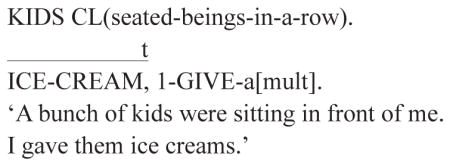

In Section 2 we observed that pronouns show idiosyncratic morphological forms for first person. First-person agreement shows similar effects. As first noted in Meier (1990), idiosyncratic first-person object verb forms are attested both in ASL (e.g., CONVINCE) and in Danish Sign Language (e.g., COMFORT; Engberg-Pedersen 1993). The first-person object form of ASL CONVINCE has final contact on the signer’s neck. However, the citation form of this verb and also the non-first person object forms are articulated in neutral space; see Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Idiosyncratic first-person object agreement

Importantly, Liddell (2003) catalogues a number of idiosyncrasies in first-person pronominals and in verb forms directed to a first-person object (a first-person ‘landmark’ in his terms). As he says, the locus used for first-person object marking is typically bilaterally central, from chest to nose height (depending on the y value of the verb’s location). However, the first-person object form of the verb REMIND is produced on the signer’s dominant shoulder, more specifically, the shoulder that is ipsilateral to the signing hand. Other verbs, such as FLIRT, have no first-person object form (although this possibility may be largely precluded on articulatory grounds; see Mathur 2000 for discussion). Liddell concludes from such evidence that, for each ASL verb, whether it has a first-person object form must be listed lexically. Furthermore, he concludes that the phonological shape of each first-person object verb form must be specified in the lexicon.

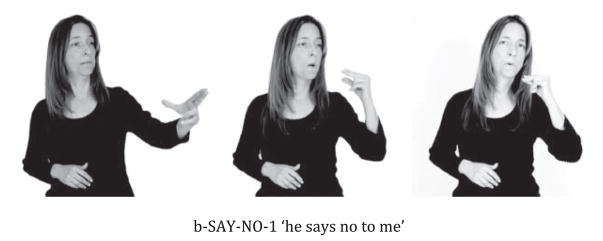

Our own view is that most first-person object forms can be described by morphological rule, although idiosyncratic forms must be lexically specified. As Liddell notes, first person-object verbs have a final location on the midline (although not necessarily in contact with the body); the height dimension of first-person object verb forms must, following Liddell (2000), be lexically specified, such that the sign INVITE moves between locations at the level of the abdomen, GIVE moves between locations that are chest-high, and SAYNO-TO (Figure 11) moves between locations that are nose-high (or slightly below it).

Figure 11.

Lexical specification for height

For verb forms that mark non-first person objects, the height dimension is again lexically-specified, but the verb’s endpoint in the horizontal plane is determined by the physical location of the referent or by the “arbitrary” location that has been assigned to that referent. In other words, our working hypothesis is this: for first and non-first person object verb forms, the x and z dimensions can be assigned by rule, but the y dimension is lexically specified. We assume that the height specification of non-first person object verb forms will be predictable from that of the citation form. An exception to this generalization is the first-person object form of REMIND, inasmuch as this first-person object form is displaced to the ipsilateral side (and thus lexical specification for the x value of the first-person object verb form is necessary).

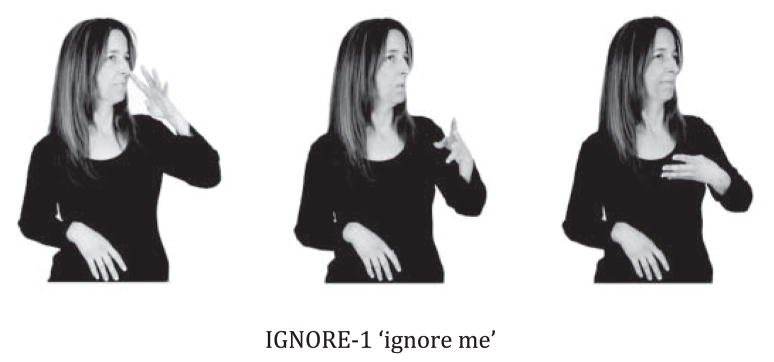

The first person object forms of some verbs allow contact on the body (e.g., GIVE); others appear to disallow it (e.g., SAY-NO-TO). Some verbs that are lexically-specified for initial contact on the body in their citation forms appear to have a height specification for their first-person object forms that is distinct from the height specification of the other directional forms belonging to these lexemes. Thus these verbs have the midline of the upper torso as their final place of articulation. This is true for first-person object forms of TELL (which has initial contact at the chin), INFORM (which has initial contact at the forehead), CALL-BY-PHONE (which has initial contact at the cheek), HONOR (which has initial contact at the forehead), and IGNORE (which has initial contact at the nose; see Figure 12). We hypothesize that this area may be a default first-person object location.

Figure 12.

Default first person object location

We take these exceptional forms as further evidence of the distinction between first and non-first person marking. Our hypothesis is that, as with the pronouns, only the first-person forms show lexical exceptions in the form of person marking. We cannot attempt a full analysis here, but we suggest that – with respect to first-person object verb forms – verb lexemes may be idiosyncratic on the following five dimensions:

Unexpected places of articulation in the first-person object forms of verbs whose citations forms are produced in neutral space: CONVINCE – neck; REMIND – ipsilateral shoulder; and, similarly to ASL REMIND, the German Sign Language verb BESCHEID-SAGEN (‘to let someone know’) – ipsilateral shoulder.9

Lexically-specified height specifications for the first-person object forms of verbs such as TELL or INFORM whose other directional forms may, on Liddell’s analysis, be produced at other heights within the sign space.

Unpredictable specification for final contact. Verbs such as GIVE allow final contact at the finger tips, but the verb ASK – specifically, the lexeme that exhibits a handshape change from a crooked index finger to an extended one – does not.

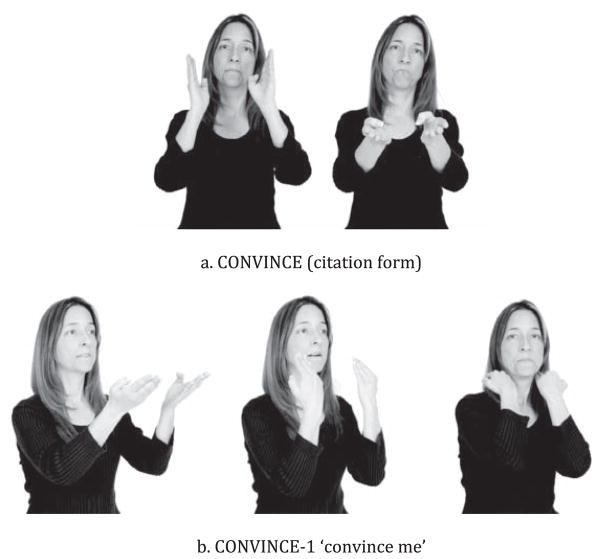

Unpredictable specification for which part of the hand is oriented toward the object; that is, unpredictable “facing”. In all directional forms of the verb GIVE the fingertips are oriented toward or “face” the object; however, TEACH is a two-faced verb – for some signers the little finger edge of the hand is oriented toward the locations of non-first person object referents, but in the first-person object form the fingertips are oriented toward the signer. See Figure 13 for photographs of two forms of the verb TEACH.

Absent first-person forms. Some verbs disallow any first-person object form (e.g., FLIRT, on the analysis of Liddell 2003). Whether such gaps in verbal paradigms are unpredictable or whether they can be explained on articulatory grounds remains a question for detailed analysis.

Figure 13.

Unpredictable facing

We conclude from this discussion of first-person object forms that directionality is a kind of person-marking, in the sense of Siewierska. Evidence for this conclusion is the distinction made between first- and non-first person object forms. Although many first-person object forms can be generated by a morphological rule, others must be separately listed in the ASL lexicon. We further conclude that directional verbs mark at least a subset of the φ-features that are marked by agreement systems generally; in most sign languages, those φ-features are person and number, but not gender.

In contrast, there is little or no evidence that a second-/third-person distinction is linguistically supported in the morphology of directional verbs, just as seems true for independent pronouns (Meier 1990). There is no difference in the forms used to express second versus third person. It is typically considered to be a universal phenomenon of language that a three-way person distinction is grammaticized (Forchheimer 1953; Lyons 1977). What, then, should be made of the apparent lack of such a distinction in sign languages?

First, it is useful to explore the putatively universal, three-way contrast further. Cysouw (2005) undertook a search for rare phenomena in the domain of person marking (including pronouns and verbal inflections). In his survey, he identified 31 languages which display syncretisms in person marking resulting in a first versus non-first distinction in the singular, and 42 in the non-singular. Of these languages, 15 blur the second/third distinction in plural independent pronouns, and one (Qawesqar, an Alcalufan language) does so in singular independent pronouns. Cysouw (2005: 242) summarizes:

Although indeed all languages may have some way to distinguish between the reference to speaker, addressee and other, it is not true that this threefold division is obligatorily made in each person marking system of every language. There are quite some cases in which the distinction between the persons is blurred to some extent.

Even if one spoken language treats person distinctions in pronouns like ASL does, the overwhelming tendency for spoken languages to mark a three-way distinction makes the person system found in ASL (and, apparently, in other signed languages) quite important typologically. We return to this point in Section 8, after we have reviewed additional factors that will contribute to our proposal. For now, we emphasize that this surprising typological property of ASL is more important to the analysis of pronouns and spatial loci than to whether verb modifications should be considered ‘person marking’ or not. For example, on an index-copying model of agreement, the verb will simply have whatever features it copies from the noun. The lack of a second-/third-person distinction in verb marking follows from its absence in the pronoun system and does not pose additional problems for the linguistic analysis.

4.3. How to treat the multiple non-first loci?

Neidle et al. (2000: 31) seem to consider the multiple non-first forms simply as multiple persons: “spatial locations constitute an overt instantiation of φ-features (specifically, person features).” They propose (p. 36) that the use of space “allows for finer person distinctions than are traditionally made in languages that distinguish grammatically only among first, second, and third person.” This is problematic, however, because these multiple non-first forms are potentially infinite, in that any location in space can be a distinctive R-locus. In practice, of course, any particular discourse is not likely to make use of more than two or three different loci, and typically these loci involve maximally contrastive spatial locations (e.g., one on the right, one on the left, one in the middle). The problem is in specifying the morpho-phonological forms of the R-loci: they cannot be listed in the mental lexicon (Lillo-Martin and Klima 1990; Rathmann and Mathur 2002). How then are the right forms derived?

Lillo-Martin and Klima (1990) discussed this issue with respect to pronouns. They proposed that there is just one (non-first)10 pronoun, not an indefinite/infinite list. Crucially, abstract grammatical referential indices in sign languages are realized overtly, through referential loci. At the abstract level, they supposed that all referring expressions are assigned a referential index. Discourse mechanisms ensure that within a discourse, co-referentiality (usually) corresponds to co-indexing (with some well-known exceptions; e.g., Rein-hart 1983). Typically, once a referent is associated with an R-locus, the same R-locus will be used for this referent throughout the discourse, unless these is some reason for the locus to change (e.g., Padden 1990 discusses cases of locus shifting when the event described involves a change of location for the referent).

Lillo-Martin and Klima proposed that in sign languages, unlike spoken languages, expressions with different referential indices will be pronounced differently (i.e., articulated toward different loci), while those with the same index will be directed toward the same locus. Thus, the indices are realized overtly.

The index sharing agreement analyses of Cormier et al. (1998) and Aronoff et al. (2005) described earlier apply this type of analysis to the agreement phenomenon. It is assumed then that there is essentially one non-first pronoun, unspecified for locus, and one non-first agreement morpheme, similarly unspecified for locus. An agreeing verb copies the index of its argument, including values for person (first/non-first) and number. Co-indexing is interpreted as coreference at the meaning level, and is expressed by directing the sign (pronoun or verb) to the same locus. Number features are expressed through the addition of the relevant markers (realized as, for example, an arc path).

5. Person marking and connections to gesture

Given the considerations discussed in Section 4, we agree with Liddell that actual real-world locations of referents are not part of the grammar, so in order for a linguistic object to ‘point to’ such locations, language must interface closely with the gestural system. Studies of the relationship between language and gesture show that they are tightly interconnected, and that both linguistic and gestural information can be expressed simultaneously in the same channel even for speech (Okrent 2002). Okrent proposes that several criteria can be applied to the problem of drawing a distinction between language and gesture. These criteria include degree of conventionalization, site of conventionalization, and restrictions on combinations. While there is not an obvious conclusion that can immediately be drawn from these criteria, we find that the first-/non-first person and number distinctions marked in directionality are of a suitable degree of conventionalization for linguistic phenomena. In addition, the restrictions on combinations of feature values are expected under the linguistic analysis (as one example, the multiple plural form can only be used with objects, while the dual and exhaustive forms can be used with subjects or objects).

On our view, the grammar doesn’t care which point in space is used for a particular referent. Abstract indices are part of the grammar,11 but loci are determined outside of grammar. Therefore, the connection between referents and loci requires language to interface with gesture. We see this combination of linguistic and gestural as equivalent to the combination of speech and gesture (cf. Lillo-Martin 2002; Rathmann and Mathur 2002). In other words, a sign language pronoun is equivalent to a spoken language pronoun plus a pointing gesture, as illustrated in Table II.

Table II.

Relationship between grammar and gesture in sign and spoken languages

| Sign language | Spoken language | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammar | IX (sign underspecified for loc) | Pronoun |

| Gesture | Location | Point to location |

On our proposal, there are some differences between the two language modalities. In spoken languages, pronoun and gesture can be unbundled, although speech and gesture are generally co-temporal. In sign languages, the pronoun and gesture (location) occupy a single perceptual channel, and therefore cannot be unbundled; they must be simultaneously articulated. Therefore, the packaging of the gesture with respect to words is different across modalities.

This view can readily be extended to directionality. We have argued that directionality is a grammatical phenomenon for person marking, and have referred to index-sharing analyses of it. The index which is shared by the verb and its argument is realized through a kind of pointing to locations which are determined on the surface by connection to para-linguistic gesture. Having reached the conclusion that directionality is person-marking, we now consider other challenges to an analysis in terms of ‘agreement’ per se.

6. More challenges

We have made the case that directionality should be considered as a type of ‘person marking’. By choosing this label, we mean to encompass a range of further, more specific analyses in terms of verb agreement or types of pronominal marking or cliticization. In this paper, we do not attempt to make such a more specific proposal. Our goal is to identify the factors that must be considered for any such proposal.

In the following subsections, we review two additional challenges to the agreement analysis. The first challenge is specifically to the analysis of directionality as morphological agreement, on a par with, for example, subject-verb agreement in Spanish. The points that are raised are troublesome for an analysis based on agreement if one considers the ‘canonical’ properties of agreement systems as proposed by Corbett (2006). As we briefly review below, sign languages show some non-canonical properties in verb directionality.12 These properties can be incorporated into an agreement analysis, but they may also be an indication that an analysis using another approach would be more successful.

The second challenge comes from consideration of the existence of highly similar patterns of directionality across different sign languages. The near ubiquity of directionality across established sign languages – and the nature of the cases lacking it – cries out for explanation just as any other linguistic generalization (see Aronoff et al. 2005 for discussion of this point).

6.1. Non-canonical aspects of directionality as agreement

If directionality is to be analyzed as agreement, it must be acknowledged that some aspects of the system are non-canonical. Here we discuss in detail two such aspects: verb classification and the relative prominence of subject versus object marking.

It has long been noted that not all verbs show directionality, and of those which do show it, not all show it in the same way. Some verbs move with respect to locations associated with person arguments (typically, these are simply called agreement verbs); others move with respect to locations such as source and goal (spatial verbs); and others show no directionality (plain verbs) at all. Padden (1983, 1990) and others assumed that whether or not a verb could take ‘agreement’ would be listed in the lexicon (in arbitrary lexical categories). Although many languages have different verb classes based on which form of agreement they take (e.g., -ar, -er, and -ir verbs in Spanish), the classification of verbs in sign languages has posed a significant hurdle to gaining a better understanding of how the system works.

Since the 1970’s, a number of authors have proposed that gaining this better understanding should start with consideration of a set of verbs which are known as ‘backwards’ verbs. In these verbs, the movement starts from the locus associated with the object, and moves toward the locus associated with the subject, ‘backwards’ from the typical subject-to-object movement (see Figure 14). Furthermore, these verbs have a clear semantic/thematic peculiarity: in the backwards verbs (including COPY, PICK, TAKE), the subject is interpreted as a goal argument, while the object is a source.

Figure 14.

Backwards verb

Friedman (1975) proposed to unify backwards verbs and regular verbs by analyzing agreement as uniformly moving from source NP to goal NP. Padden (1983) argued that this thematic analysis missed important syntactic generalizations which apply uniformly to subjects and to subject agreement, whether the verbs are regular or backwards. For example, Padden argued that the possibility of omitting agreement markers (previously noted by Meier 1982) holds of subjects, whether the verb is regular or backwards. That is, it is not source agreement marking (or goal) that can be omitted, but specifically subject marking – hence, there must be a coherent category of subject agreement.

Meir (1998, 2002) made a proposal to capture both the thematic generalization regarding direction of movement and the syntactic observations made by Padden. She noted that (in Israeli Sign Language, ISL) the facing of the hands is consistently toward the object, whether the verb is regular or backwards. A comparison of the verbs illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 14 will show the point for ASL as well. Figures 4b and 14a illustrate verbs agreeing with first-person object. In both these verbs, the palm is toward the object (‘me’), although the movement of the verb is toward the signer in Figure 4b and away from the signer in Figure 14a. Based on this observation, Meir argued that the facing of the verb marks its syntactic object. Person agreeing verbs use this mechanism, which Meir (2002) proposes is actually dative case marking rather than agreement. This step allowed Meir to separately consider the movement path, which, as Friedman noted, is consistently source-goal.

With this in mind, Meir argued that thematic structure determines agreement class. On her analysis, verbs of ‘transfer’ (whether literal or metaphorical) show person agreement. This analysis entails that the subject and object of an agreeing verb must be [+human], on the view that only humans can be possessors, so only humans can be the instigator or recipient of a transfer.13 Meir further argued that verbs denoting ‘path’ show location agreement. Both person agreement and location agreement use the direction of the movement path to mark source and goal on her account.

Meir’s proposal indicates that some semantic/thematic information may well help to establish verb categories, but there is no consensus on how to determine verb classification. Furthermore, the existence of categories of agreement-marking, location-marking, and non-agreeing verbs is typologically unusual. The classification offered by Meir is a great improvement over the arbitrary lexical listing account, yet important questions remain. For example, can verb classification be determined lexically, or does sentence context need to be taken into account? For example, many verbs, such as BLAME, SEE, and PICK, can appear with either [+human] or [−human] arguments. Do such verbs fail to mark agreement when they appear with [−human] arguments? Meir does not discuss such cases, but our data indicates that for cases like BLAME, if agreement is present with nonhuman arguments the argument is perhaps personified; for cases like SEE, it appears that agreement takes on the characteristics of location marking rather than person marking (Padden 1983; Janis 1995).

Quadros and Quer (2008, 2010) found numerous other difficulties with a thematic account such as that proposed by Meir. They claimed that verbs (in Libras and Catalan Sign Language, LSC) do not necessarily move from source to goal, citing examples having a theme or patient object (rather than goal). They also claimed that verbs may agree with inanimate objects, and that agreement may reflect both a location and a subject at the same time. They argued that there is no concrete listing of verb types; rather, verbs behave in different ways in different contexts. This conclusion is substantiated by two corpus studies (Johnston and Schembri 2007; Quadros and Lillo-Martin 2007), which found that particular verbs vary quite a bit in their realization of directionality, showing agreement with human arguments, with locatives, or no agreement at all. However, if the thematic account is abandoned, this leaves open the question of what accounts for the full range of patterns observed.

The second non-canonical aspect of directionality under the agreement analysis is the apparent primacy of object over subject marking. For example, some transitive verbs mark agreement with the object only (e.g., ANSWER), but no verbs mark agreement with only the subject (indeed, intransitive verbs are not directional). In addition, it has been observed that subject marking is optional (Meier 1982; Padden 1983). Agreement is generally seen as an obligatory (formal) phenomenon, so a system permitting agreement to be optional is already unconventional. Potentially more egregious is the observation that it is object agreement that is obligatory, while subject agreement is optional. Across spoken languages, subject agreement is much more systematic. Many languages can be identified as marking agreement systematically only with subjects, but the marking of object only is much more rare (but see Siewierska 2004, ch. 4, for discussion).

Meir et al. (2007) offer a new way of looking at the apparent primacy of object over subject marking in sign languages. They propose that for many non-agreeing verbs, the signer’s body is used to represent the subject of the action. For example, in the verb EAT, the hands move toward the signer, not because the signer’s locus represents first person, but because it represents the subject – the eater, in this example. In agreeing verbs, the signer’s body changes its function, from representing subject to representing first-person. Meir et al. propose that single-agreement verbs (such as ASLANSWER) are a hybrid – in such verbs, the body marks the subject, while the manual sign shows object agreement. On this account, subject is still marked in such verbs, although by a different mechanism than agreement.

Although this analysis is interesting in many ways, it does not completely capture the primacy of object, especially with respect to the issue of optionality of subject agreement. When subject agreement is ‘dropped’, the verb is signed from a neutral location near the signer’s locus (or to this neutral location in backwards verbs). In such forms, the signer’s body is not representing the subject any more than it does in the fully agreeing form. Something else must account for the possibility of using such a form. Neidle et al. (2000) argue that such forms represent not the absence of agreement, but a neutral agreeing form (as in a zero affix). However, it is not clear that such forms behave syntactically like forms with agreement (see Section 7).

The properties discussed in this section – the optionality of agreement, the classification of agreeing and non-agreeing verbs, the existence of two kinds of agreement, the set of backwards verbs – show that agreement in signed languages is not canonical in Corbett’s (2006) sense. However, cross-linguistic research has revealed a wide variety of agreement systems, and many of the properties that at first make sign language agreement seem unusual are in fact attested across the world’s languages. For example, ASL falls into one of the common patterns for monotransitive/ditransitive alignment observed by Haspelmath (2005); in such languages, object agreement is triggered by the patient of a monotransitive or by the recipient of a ditransitive (the so-called “primary” object), but not by the theme of a ditransitive (the “secondary” object). A related factor that conditions verb agreement in many spoken languages is animacy, such that verbs may not show agreement with NPs that are low on the animacy hierarchy (Comrie 1989).

Much future research will be necessary in order to sort through the various noncanonical properties exhibited by agreement in ASL and other signed languages.

6.2. Sign-language universality

As we have noted, similar systems of directional verbs seem to be found in all established sign languages (though not necessarily early in their emergence, as we discuss below; among many references, see Bos 1990 on Sign Language of the Netherlands (SLN); Brennan 1981 on British Sign Language; Engberg-Pedersen 1993 on Danish Sign Language (DSL); Fischer 1996 on JSL; Pizzuto et al. 1990 on Italian Sign Language; Smith 1990 on Taiwan Sign Language). Mathur (2000) conducted a comparison across four sign languages and found significant similarities in the patterns of directionality, with differences mainly due to language-specific lexical forms. Newport and Supalla (2000) and Aronoff et al. (2005) have argued that the system of verb directionality is a modality effect, present across sign languages because the modality makes available spatial resources which are brought into linguistic structure. On the view of Aronoff et al. the path movement of directional verbs is a morpheme DIR that takes agreement, that encodes transference, and that is available universally to established signed languages because of the iconic resources of the modality.

It is possible, however, to identify sign languages which do not have the tripartite division of verbs observed in established signed languages. Aronoff et al. (2004) and Meir et al. (2007) report that Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL) has spatial verbs, but not person-agreeing verbs. They attribute this to the relatively young age of the language, but its status as a ‘village sign language’ (a sign language used by both deaf and hearing members of a close-knit village) may also play a role. It is also reported that directionality is absent from some other village signed languages (Nyst in press cites Washabaugh 1986 for Providence Island Sign Language and Marsaja 2008 for Kata Kolok).

Researchers have inferred grammaticization of agreement in Nicaraguan Sign Language (LSN), which has emerged since the founding in 1977 of a school for the deaf in Managua (Senghas 2003). Senghas and Coppola (2001) analyzed the use of space in the first and second cohorts of signers to have entered the Managua school, where these cohorts were defined as having exposure to LSN before or after 1983. Second cohort signers showed significantly more spatial modulations per verb than did first cohort signers; moreover second cohort signers were more likely to use spatial locations to refer back to referents that had been previously associated with some location in space.

Within established signed languages, there is also evidence of diachronic change in directional verbs. Engberg-Pedersen (1993) has reported that older Danish signers do not mark first person objects through directionality; instead directionality is limited to non-first person objects. For these older signers, the movement of a directional verb cannot be “reversed”, thereby barring movement toward the signer (that is, toward the R-locus of a first person object). In a variety of signed languages, there is evidence that directionality is sufficiently productive that new directional verbs may be added to the lexicon. In ASL, some so-called “loan signs” that have their historical origins in the fingerspelling system have become directional verbs (Battison 1978; Padden 1998). For example, verbs derived from the fingerspelled expressions N-O and F-B (“feedback”) have been nativized as the directional verbs SAY-NO (Figure 10 above) and FEEDBACK (“to provide feeback to someone”). In Taiwan Sign Language, a sign representing the Chinese character “introduce” has been nativized as a directional verb INTRODUCE (Chen 2007).

These observations about the emergence of agreement lead to the following overall picture. Apparently, the use of spatial locations is a strong characteristic of the visual modality. Directionality is used in a wide range of circumstances; it appears in the gesture of nonsigners, the prelinguistic gesture of hearing children, and the early gestures and signs of deaf children (Casey 2003b). However, the use of directionality to mark the distinction between first- and non-first person is not quite so widespread, as illustrated by the existence of spatial but not person agreement in ABSL. Berk (2003) found a similar asymmetry in two children acquiring ASL with relatively late exposure – they produced location agreement relatively accurately, but made many errors with person agreement. Likewise, the systematization of directional verbs in LSN, the cross-generational differences in the marking of first-person objects in DSL, and the assimilation of loan signs into the set of directional verbs (resulting in the nativization of these “foreign” signs) suggest that person agreement systems do not emerge fullblown from gesture. Instead the emergence of agreement systems – whether understood as fully linguistic or fully gestural or some combination of language and gesture – takes time (Meier 2002).

An alternative proposal considers the emergence of agreement in established sign languages to be due to cliticization or incorporation of pronouns – a path for the grammaticization of inflection in many spoken languages (Fischer 1975; Pfau and Steinbach 2006). Considering directionality as cliticization might be useful in consideration of some of the non-canonical agreement properties discussed in Section 6.1 (cf. Nevins 2009). One challenge for such an approach, however, is the existence of backwards verbs in both established and young sign languages (Aronoff et al. 2004). In these verb types, the subject pronoun which appears before the verb (for S-O languages) does not share a locus with the beginning of the verb; likewise, the ending locus of the verb is not coincident with the locus of the object. One possible explanation for the differential development of directionality in backwards verbs was proposed by Quadros and Quer (2010). They suggested that backwards verbs derive from handling verbs and that they actually mark location agreement rather than subject-object agreement.

7. Morpho-syntactic properties of person marking

Our proposal is that verb directionality is a linguistic process whose realization makes contact with para-linguistic gesture. With some verbs, it is a kind of person marking, providing information about the arguments of verbs; with other verbs, it marks locatives. Our more tentative hypothesis is that these directional verbs are a manifestation of an agreement process. Given this analysis, it would be expected that certain syntactic consequences would follow. In this section we review several syntactic properties associated with verb directionality which support our view of it as agreement.

7.1. Word order

It has been observed since early studies of ASL that word order is more flexible with directional verbs than with plain verbs (Fischer 1975); see examples in (3)–(4).14

| (3) | a. | a-MARY a-HELP-b b-JOHN | SVO |

| b. | a-MARY b-JOHN a-HELP-b | SOV | |

| c. | b-JOHN a-MARY b-HELP-a | OSV | |

| ‘Mary helps John.’ | |||

| (4) | a. | a-MARY LOVE b-JOHN | SVO |

| b. | *a-MARY b-JOHN LOVE | SOV | |

| c. | *b-JOHN a-MARY LOVE | OSV | |

| ‘Mary loves John.’ |

From a functional point of view, it can be said that the marking of subject and object conveyed by directionality frees word order from this function, allowing word order to be flexible or to be used for other purposes, such as information structure. Under formal approaches, the difference between the verbs with agreement and those without might be reflected in more complex syntactic structures which open up positions for movement of subject and/or object in the former but not the latter (Quadros and Lillo-Martin 2010). In either case, recognizing the grammatical difference between the directional and plain verbs is crucial to accounting for the different syntactic effects.

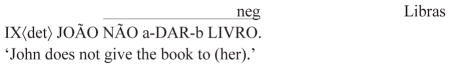

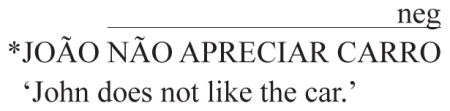

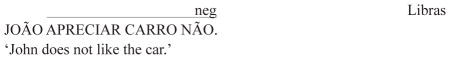

An even more striking illustration of word order differences between sentences containing directional verbs and those not marked is found in Libras (but not in ASL). In this language, the negative sign NÃO can appear in the preverbal position only with directional verbs, as shown in (5). When the verb is plain, the negative sign can only appear in the sentence-final position (6), an option also available for sentences with directional verbs.

-

(5)

-

(6)

According to the analysis proposed by Quadros (1999), this difference follows from the same difference in phrase structure for agreeing versus plain verbs mentioned earlier in this section, along with some assumptions regarding the licensing of agreeing versus plain verbs. Whatever the details of the analysis, it is clear that any analysis must treat as syntactically different the structures associated with agreeing versus non-agreeing verbs to account for the differences between them in the possibility of word order variations.

7.2. Null arguments

As commonly found in languages with ‘rich’ agreement systems, ASL (and other sign languages; see Quadros 1999 for similar data from Libras) allows the arguments of verbs with directionality to be null. Examples from Lillo-Martin (1986: 421) are given in (7)–(8).

-

(7)

- Did John send Mary the letter?

-

YES, a-SEND-b.‘Yes, (he-) sent (it) to (-her).’

-

(8)

-

a-JOHN KNOW-WELL PAPER FINISH a-GIVE-b.‘Johni knows (hei-) gave the paper to (-her).’

-

a-JOHN KNOW-WELL PAPER FINISH b-GIVE-a.‘Johni knows (shei-) gave the paper to (-him).’

-

Languages with rich agreement tend to allow null arguments, so the existence of null arguments in ASL is consistent with the analysis of directionality as agreement. As it happens, sentences with plain verbs may also contain null arguments, as illustrated in (9)–(10).

-

(9)

-

a-JOHN a-FLY-b b-CALIFORNIA LAST-WEEK.ENJOY SUNBATHE[dur].‘John flew to California last week.(He’s) enjoying a lot of sunbathing.’

-

-

(10)

- Did you eat my candy?

-

YES, EAT-UP.‘Yes, (I) ate (it) up.’

According to Lillo-Martin (1986), the null arguments with plain verbs show different syntactic behavior from those with agreeing verbs, and thus, the licensing mechanisms for these two types of null arguments are different. On this analysis, agreement itself identifies the null arguments that appear with agreeing verbs. Such a proposal crucially depends on the existence of a class of agreeing verbs with associated syntactic consequences. Bahan et al. (2000) argue contrary to Lillo-Martin that the null arguments of both verb types are licensed by agreement, but only non-manual agreement is used with plain verbs. Although this proposal differs from Lillo-Martin’s with respect to the licensing of null arguments and their syntactic type, it shares a reliance on the notion of morpho-syntactic agreement. See Koulidobrova (2010) for yet another view of the licensing of null arguments in ASL and the relationship between null arguments and verb directionality.

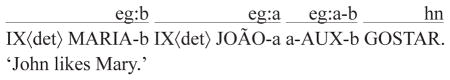

7.3. AUX

Some sign languages (though not ASL) use an auxiliary sign to show person marking with plain verbs. Authors have described similar signs across a variety of sign languages (see Steinbach and Pfau 2007 for a summary), but they have used different labels and proposed different analyses for these signs, including AUX (auxiliary; Smith 1990 for Taiwan Sign Language; Fischer 1996 for JSL; Quadros 1999 for Libras), ACT-ON (Bos 1994 for SLN), and PAM (person agreement marker; Rathmann 2000 for German Sign Language). What these various signs have in common is that, like directional verbs, they move from the locus of a subject, to the locus of an object. In some sign languages, they show up only with plain verbs; in others, they may co-occur with directional verbs.

An example of the use of AUX in Libras is given in (11). In (11a), only SVO word order is available to show the grammatical relations between the subject and the object. In (11b) and (11c), both nouns occur before the verb. It is only the presence of the AUX sign, moving from subject to object, that clarifies this relationship. In the presence of AUX, the nouns can appear in either order (S-O or O-S).

-

(11)

Although the different AUX signs show different patterns of distribution, what they have in common is directionality much like that we have called person marking. The grammatical interactions between AUX and sentence structure are highly rule-governed and language-specific. For example, in Libras the AUX virtually never co-occurs with a verb showing agreement; however, this ‘double marking’ is permitted in a range of sign languages (Steinbach and Pfau 2007). As Quadros and Quer (2010) point out, the AUX that co-occurs with backwards verbs in LSC is in fact a more straightforward marker of agreement than verb directionality is, since the path of the AUX is subject-object, not source-goal.

Steinbach and Pfau identify several different grammaticization sources of auxiliaries across sign languages, but they find a good number of them are best seen as pure markers of agreement. As with the other syntactic properties discussed in this section, the existence of such elements strongly confirms the linguistic status of directionality, and is consistent with an analysis in terms of agreement.

8. Conclusions

We have argued here that directional verbs in ASL and other signed languages are properly analyzed as marking grammatical person. A significant source of evidence for our claim came from an analysis of first-person object verb forms. The person-marking grammatical rule yields a characteristic form in regular cases. However, exceptional, irregular cases also exist. For these verb forms, it is not enough to know the citation-form verb and the spatial locations associated with its arguments. Idiosyncratic properties of these first-person verbs must be listed in the lexicon. Similar arguments led to the conclusion that the pronominal system of ASL and other signed languages encodes first person. Additional support for our claim comes from the observation that not only do directional verbs display a kind of person-marking morphology, but they also have syntactic correlates in sign order, null arguments, and auxiliary verb forms that are similar to the syntactic correlates of agreement in spoken languages. For these reasons, we not only think that directional verbs are properly considered to be person-marking morphology, but we also argue that person-marking in ASL is a morphosyntactic manifestation of verb agreement. There is much to work out yet, starting with a fuller analysis of first-person object verb forms than we have attempted here. Detailed data on the full variety of forms attested would be needed for such an analysis. Nonetheless, we maintain that person systems characterize signed and spoken languages.

Even though we use some terminology that is familiar from the analysis of spoken languages, directional verbs display many properties that make them unlike familiar verb agreement systems in spoken language. Although signed and spoken languages have personal pronouns and also person-marking in their verbal morphology, ASL does not appear to mark the range of person distinctions typical of person-marking systems in spoken languages; we find little evidence in ASL (or other signed languages) for a grammaticized (or lexicalized) distinction between second and third person.

The visual-gestural modality affords rich spatial resources to signed languages. Directional verbs draw heavily on those resources, so heavily that directional verbs and ostensive gesture are tightly bonded in signed languages. In spoken languages, where gestural support is often not available, person-marking in pronouns and agreeing verbs does more of the referential work than is done by person-marking in signed languages, where gestural support is always available. We conclude that the linguistics of person in signed and in spoken languages is affected by modality-specific properties of the transmission channel in which a given language is used.

A further concern is the ubiquity of directional verbs in national signed languages, and therefore the ubiquity of what we call agreement across these signed languages. It is possible that this problem will find its solution in an analysis of the origins of directional spatial verbs in highly iconic action gestures. We know, however, that the emergence of systems of directional verbs in national signed languages can take time. We also know that, to our surprise, some village signed systems, notably ABSL, appear to make no use of person-marking verbs, but are instead reliant on word order to mark argument structure. An important issue therefore is: how does the grammaticization of agreement proceed in signed languages and why is the outcome so uniform, given that some nascent signed languages seem to make little systematic use of directionality? In spoken languages, agreement generally begins with the grammaticization of once-independent pronouns. This route may well be available in signed languages, but there also may be another route that begins in the reanalysis of action gestures. A particular test for these competing treatments of the emergence of agreement will likely be the class of backward verbs that we discussed earlier. We speculate that different language modalities may clear different grammaticization paths, but leading to a common endpoint (person-marking).

There are other issues that we have not addressed here, notably the acquisition of directional verbs by signing children. This is an issue about which we have each had much to say in the past (e.g., Meier 1982, 2002; Lillo-Martin 1991; Quadros and Lillo-Martin 2007). The analysis of the acquisition of directional verbs is complicated by many of the linguistic issues that we have touched on here (e.g., the apparent optionality of directionality in many linguistic contexts); resolution of issues in the linguistics of directionality will immediately inform acquisition research. However, acquisition research will also inform linguistic work: in particular, we think that continued analyses of ontogenetic change in children’s knowledge and use of directional verbs may have much to say about how agreement emerged diachronically within particular signed languages. Children may make unique contributions to the emergence of signed languages. In the linguistic analysis of agreement in signed languages, in the analysis of how agreement emerges over time, and in the analysis of how agreement is acquired over the timecourse of child development, we leave many unresolved issues. We hope that we have convinced you that the resolution of these issues has implications beyond the research community that focuses on the linguistic analysis of signed languages.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Award Number R01DC000183 from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health. Additional support came from the Robert D. King Centennial Professorship of Liberal Arts at UT Austin.

We sincerely thank our sign consultants, models, illustrators, and research assistants: Stella Egbert, Lynn Hou, Laura Levesque, Kirsi Grigg, Annie Marks, Frank A. Paul, Franky Ramont, Brenda Scherz, Doreen Simons, and Sam Supalla.

Appendix

| Notational Conventions | |

|---|---|

| SIGN | Signs are glossed using upper-case (near) translation equivalents. |

| SIGN-SIGN | If the translation equivalent for a single sign requires more than one written word, the words are conjoined with a hyphen. |

| IX | Pointing signs are glossed using IX. |

| 1-SIGN-b | Spatial loci used to indicate referents are marked as prefixes (for the starting point) or suffixes (for the ending point). ‘1’ is used for first-person locus; different letters stand for different loci in an utterance. |