Abstract

Introduction

Children presenting for the first time with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) offer a unique opportunity to study aetiological agents before the confounders of treatment. Microaerophilic bacteria can exploit the ecological niche of the intestinal epithelium; Helicobacter and Campylobacter are previously implicated in IBD pathogenesis. We set out to study these and other microaerophilic bacteria in de-novo paediatric IBD.

Patients and Methods

100 children undergoing colonoscopy were recruited including 44 treatment naïve de-novo IBD patients and 42 with normal colons. Colonic biopsies were subjected to microaerophilic culture with Gram-negative isolates then identified by sequencing. Biopsies were also PCR screened for the specific microaerophilic bacterial groups: Helicobacteraceae, Campylobacteraceae and Sutterella wadsworthensis.

Results

129 Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterial isolates were identified from 10 genera. The most frequently cultured was S. wadsworthensis (32 distinct isolates). Unusual Campylobacter were isolated from 8 subjects (including 3 C. concisus, 1 C. curvus, 1 C. lari, 1 C. rectus, 3 C. showae). No Helicobacter were cultured. When comparing IBD vs. normal colon control by PCR the prevalence figures were not significantly different (Helicobacter 11% vs. 12%, p = 1.00; Campylobacter 75% vs. 76%, p = 1.00; S. wadsworthensis 82% vs. 71%, p = 0.312).

Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive overview of the microaerophilic microbiota of the paediatric colon including at IBD onset. Campylobacter appear to be surprisingly common, are not more strongly associated with IBD and can be isolated from around 8% of paediatric colonic biopsies. S. wadsworthensis appears to be a common commensal. Helicobacter species are relatively rare in the paediatric colon.

Trial Registration

This study is publically registered on the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network Portfolio (9633).

Introduction

Paediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) represents a variant phenotype characterised by more extensive disease activity at onset and a progressive course [1]. Immunological differences can be identified between paediatric and adult Crohn’s disease (CD) [2]. While paediatric disease represents a distinct phenotype of IBD, it is surprisingly not explained by a significantly different genotype [3]. One implication might be that the paediatric phenotype is an expression of different environmental triggers rather than inherited factors. Recent studies showing a rise in the incidence of IBD in childhood and, perhaps more worryingly, a younger age at onset in those affected support an urgent need for aetiological studies to explain these trends [4]–[7]. The discovery that the use of antibiotics early in life and in multiple courses confers an increased risk of subsequent IBD development demonstrates the importance of microbial perturbation in disease development [8], [9]. Recent genetic discoveries reinforce the essential role for host defence against infection in IBD pathogenesis [10].

The biological importance of the gastrointestinal microbiota and its symbiotic relationship with the human host is now firmly established [11], [12]. It is increasingly clear that disturbance of the resident microbiota can induce human disease, with the most studied example being the “dysbiosis” of IBD and its resultant inflammation [13], [14]. The route from health to IBD through dysbiosis is unclear but may involve a trigger event such as bacterial infection [15], [16]. We recently postulated that Proteobacteria with adherent and invasive properties may exploit weaknesses in host defences to drive this dysbiotic change [16]. Helicobacter species (microaerophilic members of the Epsilonproteobacteria; “microaerophilic” describing bacteria that thrive in low oxygen concentrations) have been shown to initiate IBD in both rodent and primate models and may also be implicated in infectious proctitis in humans [17]. Conflicting evidence exists from human studies to support Helicobacter as agents in human IBD [18]–[26]; nevertheless the compelling animal data has made the genus worthy of consideration as a potential pathogen in IBD. Campylobacter concisus (another microaerophilic Epsilonproteobacterium) was cultured from mucosal biopsies from a paediatric CD patient by Zhang et al [27]. This organism has since been shown to be more prevalent in IBD and to be capable of adhering to and invading epithelial cells and driving a pro-inflammatory change [28]–[31].

Much of the current literature on IBD microbiology utilises convenient cohorts of patients with established disease, potentially introducing major confounders when interpreting results [32]. Paediatric IBD offers an opportunity to explore these problems, since children are relatively free of additional significant co-morbidities and are generally treatment naïve at IBD diagnosis. For these reasons we set up the “Bacteria in Inflammatory bowel disease in Scottish Children Undergoing Investigation before Treatment” (BISCUIT) study, with the specific aims of:

Recruiting a robustly described, prospective clinical cohort of newly presenting children with untreated IBD alongside children with normal colons as controls

Isolating and identifying microaerophilic bacteria (particularly Helicobacter and Campylobacter) that may be of clinical relevance at the onset of IBD

Confirming the true prevalence of specific microaerophilic organisms within the colonic mucosa by molecular methods.

The BISCUIT study recruited 100 Scottish children over a 30 month period. The data contained within this paper documents the isolation and identification of microaerophilic bacteria alongside the molecular (true) prevalence of Helicobacter and Campylobacter species and Sutterella wadsworthensis within colonic biopsies from the entire BISCUIT cohort. In a complementary but distinct analysis we previously published a full hypothesis-free bacterial diversity assessment using pyrosequencing on a subset of the cohort (37 BISCUIT subjects in total) [32].

Methods

Patients were recruited to the BISCUIT study from elective colonoscopy lists in three paediatric centres (Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital, Aberdeen; Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow and Ninewells Hospital, Dundee). An approach with study information was made either on the day of admission (the day before endoscopy) or by post in advance of admission. Patients were excluded if they received systemic antibiotics or steroids 3 months prior to their colonoscopy, immunosuppression at any time, or if they had a previous IBD diagnosis. IBD investigations were as per the Porto criteria. IBD diagnosis and phenotype were assigned with reference to the Lennard-Jones, Montreal and Paris criteria (Table S2) [33]–[36]. Comprehensive clinical data were also collected at recruitment by a single investigator through use of a standardised verbal questionnaire.

Initial recruitment was into two macroscopically-defined categories, those with likely IBD, at first presentation, with macroscopic colonic inflammation and those undergoing colonoscopy who subsequently had a normal colon macroscopically. Final diagnosis and disease categorisation was assigned once endoscopic, histological and radiological investigations were complete after a minimum of six months follow-up.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was granted by North of Scotland Research Ethics Service (09/S0802/24) on behalf of all participating centres and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all subjects. Informed assent was also obtained from older children who were deemed capable of understanding the nature of the study.

This study is publically registered on the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network Portfolio (9633).

Biopsies were taken from a single site, from the distal colon in controls (rectum/sigmoid) or from the most distal inflamed site in those with colonic inflammation. 5–6 biopsies were collected using standard endoscopic forceps from all recruits. 1–2 biopsies were used for microaerophilic culture work by transferring these biopsies immediately into individual 2 ml screw-top containers with ∼700 µl Brucella broth which were incubated at room temperature until plated. 2–3 biopsies were collected for DNA analysis into a sterile 1.5 ml Eppendorf container and placed immediately onto ice before transfer to −80°C storage. The remaining biopsy was collected in paraformaldehyde for future fluorescent in-situ hybridisation studies.

Culture work was performed as described in Mukhopadhya et al [37] utilising five selective plates and one plain blood agar plate, each incubated in microaerophilic gas conditions generated by Anoxomat® (Mart® Microbiology, Drachten, Netherlands) and reviewed twice weekly for up to one month. Gram-negative and oxygen sensitive (by virtue of failed subculture in room air) bacterial isolates were identified by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. A minimum read length of 400 bp was obtained for attributing bacterial identities, the result of which was searched against the NCBI BLAST database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

DNA extraction of mucosal biopsies was performed using the commercially available Qiagen QIAamp Mini kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) with minor modifications as described previously [25]. A test polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with biopsy DNA was performed utilising universal bacterial primers to confirm the suitability of the DNA for further analysis (Table S1) [38]. Conventional PCR was undertaken to determine the prevalence of Helicobacter genus, Campylobacter genus and Sutterella wadsworthensis using primers and conditions described previously (Table S1) [25], [30], [37]. PCR products from Helicobacter and Campylobacter genus reactions were either directly sequenced on an Applied Biosystems model 3730 automated capillary DNA sequencer or cloned first into JM109 competent cells with pGEM-T-easy vector if sequence analyses indicated a mixed sequencing profile [30].

Helicobacter pylori serology was performed using the Premier H. pylori enzyme immunoassay which detects IgG antibody (Meridian Bioscience).

All statistical comparisons were undertaken using SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM Software 2010).

Results

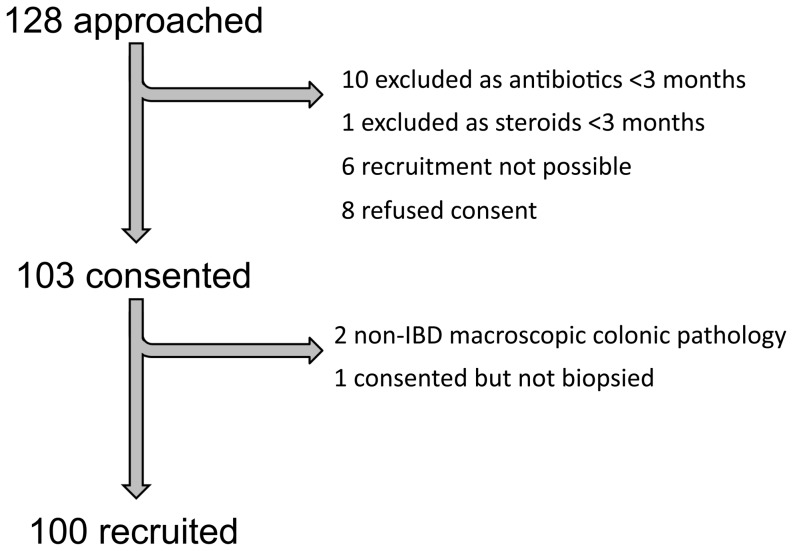

128 Scottish children were approached for the study with 100 being recruited ( Figure 1 ). Final categorisation was based on a thorough review of macroscopic, microscopic and available radiological data and is presented in Table 1 and Table 2 alongside categorical, demographic and numerical clinical data respectively. 44 IBD subjects were diagnosed as CD (29), ulcerative colitis (UC) (13) and IBD-type unclassified (IBD-U) (2). Individual IBD phenotypes are shown in Table S2. Granulomata were identified in at least one biopsy site in 21 of 29 (72.4%) CD recruits. A priori, the intention was to compare IBD recruits against those with a normal colon, however in order to achieve this, those with microscopic pathology were further sub-categorised. “Normal colon control” subjects had both a macroscopically and microscopically normal colon. “Eosinophilic controls” had histologically significant eosinophilic infiltration of their colonic mucosa in at least one site. “Non-specific inflamed, non-IBD” subjects had microscopic evidence of inflammation but insufficient grounds for an IBD diagnosis. The single “proto-IBD” recruit would have been classified within the “eosinophilic control” category but has since been re-evaluated and has subsequently developed CD. Data from each of these latter three phenotypic groups are presented in full; however statistical analyses compare the IBD and normal colon control groupings only.

Figure 1. Recruitment flowchart of recruits to BISCUIT study.

Those where recruitment was not possible were approached by post but could not then be recruited on their day of colonoscopy. The one child consented but not biopsied was due to unavailability of the investigator on the day in question.

Table 1. BISUIT Study Categorical Clinical Data.

| Eosinophilic control | IBD | Crohn’s disease | IBD-type unspecified | Ulcerative colitis | Non-specific inflamed non-IBD | NormalColoncontrol | Proto-IBD | AllRecruits | IBD vs. Normal Colon ControlFisher’s Exact Test (2-sided) | |

| Total number | 7 | 44 | 29 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 42 | 1 | 100 | |

| Male (%) | 3 (42.9) | 30 (68.2) | 20 (69.0) | 1 (50) | 9 (69.2) | 2 (33.3) | 33 (78.6) | 1 (100) | 69 (69.0) | 0.334 |

| Concurrent upper endoscopy (%) | 6 (85.7) | 44 (100) | 29 (100) | 2 (100) | 13 (100) | 2 (33.3) | 35 (83.3) | 1 (100) | 88 (88.0) | 0.005 |

| Evidence of histological gastritis(% of upper endoscopies) | 4 (66.7) | 38 (86.4) | 27 (93.1) | 1 (50.0) | 10 (76.9) | 0 (0) | 12 (34.3) | 1 (100) | 55 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| H. pylori on histology(% of upper endoscopies) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.7) | 0.035 |

| Symptoms over duration of illness (yes/no) | ||||||||||

| Abdominal Pain (%) | 7 (100) | 35 (79.5) | 23 (79.3) | 2 (100) | 10 (76.9) | 4 (66.7) | 36 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 82 (82.0) | 0.573 |

| Diarrhoea (%) | 5 (71.4) | 37 (84.1) | 23 (79.3) | 2 (100) | 12 (92.3) | 3 (50.0) | 25 (59.5) | 1 (100) | 71 (71.0) | 0.016 |

| Tenesmus (%) | 4 (57.1) | 30 (68.2) | 18 (62.1) | 1 (50.0) | 11 (84.6) | 2 (33.3) | 24 (57.1) | 1 (100) | 61 (61.0) | 0.373 |

| Blood in stool (%) | 5 (71.4) | 31 (70.5) | 16 (55.2) | 2 (100) | 13 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (57.1) | 1 (100) | 67 (67.0) | 0.262 |

| Constipation (%) | 2 (28.6) | 16 (36.4) | 12 (41.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (50.0) | 11 (26.2) | 0 (0) | 32 (32.0) | 0.358 |

| Blood on wiping bottom (%) | 6 (85.7) | 29 (65.9) | 17 (58.6) | 1 (50.0) | 11 (84.6) | 5 (83.3) | 17 (40.5) | 1 (100) | 58 (58.0) | 0.03 |

| Anorexia (%) | 3 (42.9) | 31 (70.5) | 22 (75.9) | 1 (50.0) | 8 (61.5) | 1 (16.7) | 14 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 49 (49.0) | 0.001 |

| Nausea (%) | 3 (42.9) | 17 (38.6) | 14 (48.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (33.3) | 14 (33.3) | 1 (100) | 37 (37.0) | 0.658 |

| Vomiting (%) | 3 (42.9) | 10 (22.7) | 8 (27.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) | 1 (100) | 20 (20.0) | 0.258 |

| Heartburn (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) | 10 (23.8) | 0 (0) | 17 (17.0) | 0.423 |

| Parentally reported weight loss (%) | 1 (14.3) | 25 (56.8) | 18 (62.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (53.8) | 0 (0) | 19 (45.2) | 0 (0) | 45 (45.0) | 0.388 |

| Parentally reported poor growth (%) | 2 (28.6) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (17.2) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 13 (13.0) | 0.522 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||

| Asthma (%) | 3 (42.9) | 10 (22.7) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 1 (100) | 21 (21.0) | 0.409 |

| Eczema (%) | 1 (14.3) | 10 (22.7) | 9 (31.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 1 (100) | 19 (19.0) | 0.409 |

| Hayfever (%) | 3 (42.9) | 13 (29.5) | 8 (27.6) | 2 (100) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) | 0 (0) | 22 (22.0) | 0.063 |

| Allergies (%) | 3 (42.9) | 8 (18.2) | 6 (20.7) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (33.3) | 9 (21.4) | 1 (100) | 23 (23.0) | 0.79 |

| Any previous surgery/proceduresunder anaesthetic (%) | 2 (28.6) | 12 (27.3) | 7 (24.1) | 0 (0) | 5 (38.5) | 2 (33.3) | 17 (40.5) | 0 (0) | 33 (33.0) | 0.255 |

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery/proceduresunder anaesthetic (%) | 2 (28.6) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) | 0 (0) | 15 (15.0) | 0.758 |

| Previous non-gastrointestinalsurgery/procedures under anaesthetic (%) | 1 (14.3) | 8 (18.2) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (16.7) | 15 (35.7) | 0 (0) | 25 (25.0) | 0.089 |

| Neonatal History | ||||||||||

| Vaginal delivery (%) | 7 (100) | 35 (79.5) | 24 (82.8) | 1 (50.0) | 10 (76.9) | 4 (66.7) | 35 (83.3) | 1 (100) | 82 (82.0) | 0.784 |

| Breastfed initially (%) | 3 (42.9) | 19 (43.2) | 15 (51.7) | 1 (50.0) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (33.3) | 13 (31.0) | 0 (0) | 37 (37.0) | 0.265 |

| Drug History | ||||||||||

| Previous antibiotics (%) | 6 (85.7) | 40 (90.9) | 27 (93.1) | 2 (100) | 11 (84.6) | 5 (83.3) | 39 (92.9) | 1 (100) | 91 (91.0) | 1.0 |

| Previous steroids (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (100) | 8 (8.0) | 1.0 |

| Previous acid suppression (%) | 1 (14.3) | 11 (25.0) | 8 (27.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (33.3) | 11 (26.2) | 0 (0) | 25 (25.0) | 1.0 |

| Social History | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity white UK (%) | 7 (100) | 41 (93.2) | 26 (89.7) | 2 (100) | 13 (100) | 6 (100) | 40 (95.2) | 1 (100) | 95 (95.0) | 1.0 |

| Smoking at home (%) | 4 (57.1) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (66.7) | 13 (31.0) | 0 (0) | 28 (28.0) | 0.128 |

| Pets at home (%) | 7 (100) | 32 (72.7) | 23 (79.3) | 2 (100) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (83.3) | 32 (76.2) | 1 (100) | 77 (77.0) | 1.0 |

| Total number | 7 | 44 | 29 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 42 | 1 | 100 | |

Table 2. BISCUIT Study Demographic and Numerical Clinical Data.

| Eosinophilic control | IBD | Crohn’s disease | IBD-type unspecified | Ulcerative colitis | Non-specific inflamednon-IBD | Normal colon control | Proto-IBD | All Recruits | IBD vs. Normal Colon Controlt-Test (2-tailed) | |

| Total number | 7 | 44 | 29 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 42 | 1 | 100 | |

| Age (years) | 10.3 (+/−3.6) | 11.9 (+/−2.9) | 11.9 (+/−3.0) | 12.0 (+/−2.0) | 11.7 (+/−2.9) | 7.9 (+/−5.3) | 10.6 (+/−3.5) | 8.2 | 11.0 (+/−3.5) | 0.067 |

| Height Z-score | −0.67 (+/−0.89) | −0.20 (+/−1.28) | −0.42 (+/−1.27) | 0.26 (+/−0.11) | 0.22 (+/−1.32) | 0.72 (+/−1.40) | 0.08 (+/−1.16) | 0.98 | −0.02 (+/−1.23) | 0.285 |

| Weight Z-score | −0.15 (+/−0.84) | −0.44 (+/−1.29) | −0.70 (+/−1.39) | 0.16 (+/−0.27) | 0.05 (+/−1.01) | 0.67 (+/−0.81) | 0.77 (+/−1.90) | 0.40 | 0.16 (+/−1.62) | 0.001 |

| BMI Z-Score | 0.28 (+/−0.97) | −0.53 (+/−1.39) | −0.74 (+/−1.46) | 0.04 (+/−0.37) | −0.15 (+/−1.29) | 0.48 (+/−1.03) | 0.82 (+/−1.70) | −0.27 | 0.15 (+/−1.60) | <0.001 |

| Symptom duration (months) | 41.9 (+/−60.6) | 9.2 (+/−12.6) | 9.3 (+/−14.0) | 16.0 (+/−11.3) | 7.7 (+/−9.7) | 19.2 (+/−6.3) | 23.3 (+/−20.4) | 18 | 18.1 (+/−23.5) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.5 (+/−1.6) | 11.6 (+/−1.6) | 11.6 (+/−1.4) | 11.5 (+/−2.7) | 11.8 (+/−2.1) | 11.8 (+/−1.1) | 13.4 (+/−1.5) | 12.7 | 12.4 (+/−1.7) | <0.001 |

| White cell count (x109/l) | 8.4 (+/−1.0) | 9.2 (+/−3.3) | 9.1 (+/−3.2) | 6.1 (+/−2.2) | 9.9 (+/−3.7) | 6.9 (+/−0.6) | 7.2 (+/−2.9) | 10.8 | 8.3 (+/−3.1) | 0.007 |

| Platelet count (x109/l) | 330.5 (+/−84.9) | 439.0 (+/−161.0) | 461.9 (+/−159.0) | 293.5 (+/−47.4) | 407.8 (+/−167.6) | 309.3 (+/−46.5) | 300.7 (+/−69.6) | 338 | 370.3 (+/−138.7) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive Protein (g/dl) | 5.7 (+/−3.4) | 21.8 (+/−25.0) | 26.0 (+/−28.2) | 4.5 (+/−2.1) | 13.6 (+/−)11.6 | 4.0 (+/−3.4) | 5.8 (+/−5.7) | 6 | 13.3 (+/−19.3) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 43.8 (+/−5.6) | 35.9 (+/−6.9) | 34.8 (+/−6.8) | 39.5 (+/−6.4) | 38.2 (+/−7.2) | 42.0 (+/−5.5) | 44.5 (+/−2.9) | N/A | 40.1 (+/−6.9) | <0.001 |

| Gestation at birth (weeks) | 37.9 (+/−2.0) | 39.8 (+/−1.6) | 39.9 (+/−1.5) | 40.3 (+/−0.4) | 39.4 (+/−1.9) | 39.6 (+/−0.9) | 39.6 (+/−2.4) | 40 | 39.6 (+/−2.0) | 0.748 |

| Birth weight (Kg) | 2.84 (+/−0.37) | 3.54 (+/−0.60) | 3.50 (+/−0.54) | 3.53 (+/−0.66) | 3.66 (+/−0.74) | 3.44 (+/−0.41) | 3.30 (+/−0.59) | 3.69 | 3.39 (+/−0.60) | 0.073 |

| Age at weaning (months) | 6.1 (+/−2.4) | 4.6 (+/−1.2) | 4.6 (+/−1.2) | 6.0 | 4.3 (+/−1.3) | 5.5 (+/−0.9) | 4.5 (+/−1.3) | 5 | 4.7 (+/−1.4) | 0.895 |

| Total number | 7 | 44 | 29 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 42 | 1 | 100 |

Comparisons of clinical data are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 . Histological gastritis was more common in the IBD cohort than normal colon controls who underwent gastroscopy (p<0.001; Table 1 ). Conversely, histological identification of H. pylori was higher in the normal colon controls and absent in the IBD cohort (p = 0.035; Table 1 ).

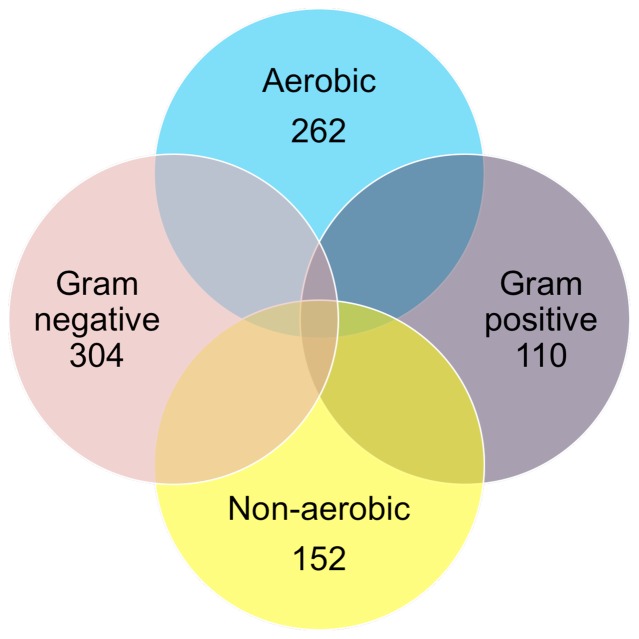

Of 555 attempted bacterial subcultures, 494 demonstrated some growth within 7 days, with 414 yielding sufficient growth to allow Gram-staining and aerobic subculture challenge to be completed ( Figure 2 ). 129 bacterial isolates met the requirements for further identification (Gram-negative but failed aerobic subculture). Of these, 114 yielded sufficient growth for DNA based identification. 112 were confirmed as Gram-negative microaerophilic bacteria after formal sequence identification. The formal identities of these 112, including 73 distinct patient isolates, are presented in Table 3 . The identities of the remaining two isolates matched two separate Gram-positive species (Bifidobacterium longum and Enterococcus faecalis) hence they were removed.

Figure 2. Basic phenotypic assessment of 414 bacterial isolates obtained from the paediatric colonic mucosa.

129 were both Gram-negative and non-aerobic, of which 114 were formally identified by sequencing.

Table 3. Bacterial Isolates Identified based on 16S rDNA sequencing.

| Isolate | Number of SubculturesObtained (May include duplicates from same patientderived fromdifferent growth media) | DistinctPatientIsolates | Source | 16SSequenceLength | PercentageSimilarityon BLAST |

| Alistipes finegoldii | 1 | 1 | IBD-type unspecified | 515 bp | 100% |

| Bacteroides caccae | 3 | 2 | Non-specific inflamednon-IBD (1), IBD-typeunspecified (1) | 513–795 bp | 99% |

| Bacteroides dorei | 1 | 1 | Normal colon control | 684 bp | 100% |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 | 1 | Crohn’s disease | 526 bp | 99% |

| Bacteroides nordii | 1 | 1 | Normal colon control | 566 bp | 99% |

| Bacteroides ovatus | 2 | 2 | Normal colon control (2) | 433 bp | 99% |

| Bacteroides salyersiae | 2 | 1 | IBD-type unspecified (2) | 697 bp, 823 bp | 99% |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | 1 | 1 | Crohn’s disease | 415 bp | 100% |

| Bacteroides uniformis | 1 | 1 | Normal colon control | 503 bp | 99% |

| Butyricimonas virosa | 2 | 2 | Normal colon control (1), IBD-type unspecified (1) | 569 bp, 676 bp | 98–99% |

| Campylobacter concisus | 6 | 3 | Crohn’s disease (2), Ulcerative colitis (1) | 1357–1423 bp | 99–100% |

| Campylobacter curvus | 1 | 1 | Normal colon control | 1537 bp | 99% |

| Campylobacter lari | 1 | 1 | Normal colon control | 647 bp | 100% |

| Campylobacter rectus | 1 | 1 | Normal colon control | 401 bp | 100% |

| Campylobacter showae | 6 | 3 | Normal colon control (2), Crohn’s disease (1) | 1325–1422 bp | 99% |

| Eikenella corrodens | 2 | 1 | Crohn’s disease | 776–802 bp | 99–100% |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | 8 | 7 | Crohn’s disease (3), Ulcerative colitis (2),Normal colon control (2) | 455–807 bp | 99–100% |

| Odoribacter splanchnicus | 1 | 1 | Eosinophilic control | 819 bp | 99% |

| Parabacteroides distasonis | 7 | 7 | Normal colon control (6),Ulcerative colitis (1) | 412–786 bp | 99% |

| Sutterella wadsworthensis | 61 | 32 | Normal colon control (11), Crohn’sdisease (8), Ulcerative colitis (6),Eosinophilic control (3),Non-specific inflamed non-IBD (2),IBD-type unspecified (1), Proto-IBD (1) | 411–1423 bp | 97–100% |

| Terrahaemophilus aromaticivorans | 3 | 3 | Crohn’s disease (1), Ulcerativecolitis (1), Normal colon control (1) | 554 672 bp | 99% |

| Total | 112 | 73 |

PCR prevalence data and Helicobacter pylori serology results for each of the phenotypic categories are shown in Table 4 and for each of the subjects in Table S2. There was no significant difference in PCR prevalence for Helicobacter, Campylobacter or Sutterella wadsworthensis between the IBD cohort and normal colon controls (Table 4). No H. pylori seropositive subject was positive for Helicobacter PCR and vice-versa. Table 5 documents Campylobacter PCR sequencing data to species-level stratified by clinical phenotype. It is apparent from the data that individuals can harbour multiple distinct species. Of the 72 positive subjects, 44 had a single Campylobacter identified with two species being identified in 17 and three species in the remaining 11 ( Table 6 ). Campylobacter curvus, Campylobacter gracilis and Campylobacter ureolyticus were never identified in isolation. The Helicobacter sequencing data was far less complex with only 12 subjects yielding positive PCR product. Of these, 5 were from normal colon controls, 5 from IBD (4 CD, 1 UC) and 2 were from eosinophilic controls. After sequencing the PCR product, 8 of the 12 (4 normal colon controls, 2 IBD- both CD, 2 eosinophilic controls) were identified as Wolinella succinogenes, another Epsilonproteobacteria and member of the Helicobacteraceae. The four remaining Helicobacter positive results were not identifiable by direct sequencing and underwent cloning and sequencing analysis. This revealed the presence of both W. succinogenes and Helicobacter brantae (from a CD patient) and confirmed the presence of Helicobacter hepaticus from a second CD patient. The two remaining patient samples remained unidentifiable despite repeated cloning attempts.

Table 4. PCR Prevalence and Helicobacter pylori Serology Data from BISCUIT Study.

| Helicobacter pylori Serology Positive | Helicobacter Genus PCR Positive | Campylobacter Genus PCR Positive | Sutterella wadsworthensis PCR Positive | Total Subjects | |

| IBD | 1 (2.3%) | 5 (11.4%) | 33 (75.0%) | 36 (81.8%) | 44 |

| (Crohn’s disease) | 0 (0%) | 4 (13.8%) | 22 (75.9%) | 23 (79.3%) | 29 |

| (Ulcerative colitis) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (7.7%) | 9 (69.2%) | 11 (84.6%) | 13 |

| (IBD-type unspecified) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 2 |

| Normal colon control | 6 (14.3%) | 5 (11.9%) | 32 (76.2%) | 30 (71.4%) | 42 |

| Eosinophilic control | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 4 (57.1%) | 7 (100%) | 7 |

| Non-specific inflamed non-IBD | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 5 (83.3%) | 6 |

| Proto-IBD | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 |

| Total | 8 (8.0%) | 12 (12.0%) | 72 (72.0%) | 79 (79.0%) | 100 |

| IBD vs. Normal colon control by Fisher’sexact test (2-sided, n = 86) | p = 0.055 | p = 1.00 | p = 1.00 | p = 0.312 |

Table 5. Campylobacter Results Obtained Through Sequence Analysis.

| Campylobacter Genus PCR Positive | Campylobacter concisus | Campylobacter curvus | Campylobacter gracilis | Campylobacter hominis | Campylobacter lari | Campylobacter rectus | Campylobacter showae | Campylobacter ureolyticus | TotalSubjects | |

| IBD | 33 (75.0%) | 17 (38.6%) | 2 (4.5%) | 1 (2.3%) | 15 (34.1%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (2.3%) | 14 (31.8%) | 0 (0%) | 44 |

| (Crohn’s disease) | 22 (75.9%) | 13 (44.8%) | 2 (6.9%) | 1 (3.4%) | 9 (31.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (31.0%) | 0 (0%) | 29 |

| (Ulcerative colitis) | 9 (69.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0 (0%) | 13 |

| (IBD-type unspecified) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 |

| Normal colon control | 32 (76.2%) | 16 (38.1%) | 3 (7.1%) | 2 (4.8%) | 14 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.5%) | 9 (21.4%) | 2 (4.8%) | 42 |

| Eosinophilic control | 4 (57.1%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 0 (0%) | 7 |

| Non-specific inflamed non-IBD | 3 (50.0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 |

| Proto-IBD | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%)0 | 1 |

| Total | 72 (72.0%) | 37 (37.0%) | 5 (5.0%) | 3 (3.0%) | 31 (31.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 6 (6.0%) | 26 (26.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 100 |

Table 6. Campylobacter Sequencing Results at Species-Level by Number of Species per Subject.

| Single Species | Number of Subjects | Source |

| Campylobacter concisus | 18 | Normal colon control (6), Crohn’s disease (8), Ulcerative colitis (2), Non-specific inflamed non-IBD (2) |

| Campylobacter hominis | 10 | Normal colon control (5), Crohn’s disease (1), Ulcerative colitis (2), Non-specific inflamed non-IBD (1), IBD-type unspecified (1) |

| Campylobacter lari | 1 | Crohn’s disease (1) |

| Campylobacter rectus | 5 | Normal colon control (3), Eosinophilic control (1), IBD-type unspecified (1) |

| Campylobacter showae | 10 | Normal colon control (5), Crohn’s disease (2), Ulcerative colitis (2), Eosinophilic control (1) |

| Total | 44 | |

| Two Species | Number of Subjects | Source |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter curvus | 2 | Normal colon control (1), Crohn’s disease (1) |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter hominis | 5 | Normal colon control (4), Crohn’s disease (1) |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter showae | 2 | Normal colon control (1), Eosinophilic control (1) |

| Campylobacter gracilis+Campylobacter hominis | 1 | Crohn’s disease (1) |

| Campylobacter gracilis+Campylobacter showae | 1 | Normal colon control (1) |

| Campylobacter hominis+Campylobacter showae | 5 | Crohn’s disease (4), Ulcerative colitis (1) |

| Campylobacter hominis+Campylobacter ureolyticus | 1 | Normal colon control (1) |

| Total | 17 | |

| Three Species | Number of Subjects | Source |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter curvus+Campylobacter showae | 2 | Normal colon control (1), Crohn’s disease (1) |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter curvus+Campylobacter hominis | 1 | Normal colon control (1) |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter gracilis+Campylobacter hominis | 1 | Normal colon control (1) |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter hominis+Campylobacter rectus | 1 | Normal colon control (1) |

| Campylobacter concisus+Campylobacter hominis+Campylobacter showae | 5 | Crohn’s disease (2), Ulcerative colitis (2), Eosinophilic control (1) |

| Campylobacter hominis+Campylobacter showae+Campylobacter ureolyticus | 1 | Normal colon control (1) |

| Total | 11 |

Discussion

This study comprehensively describes the microaerophilic microbiota of the paediatric colon with specific reference to untreated, new-onset paediatric IBD and also those with a normal colon. Our main findings are of a high molecular prevalence and culture recovery rate of unusual Campylobacter species and S. wadsworthensis and of a low molecular prevalence of Helicobacteraceae. There was no difference in the prevalence of microaerophilic species between IBD patients and controls. We acknowledge that the microaerophilic microbiota comprises a relatively small proportion of the bacterial community present within the colon, with the majority of species being obligate anaerobes. Evidence supporting a role for these microaerophilic species in IBD cannot however be ignored and they are therefore worthy of targeted study.

The possibility that Helicobacter species may be involved in IBD pathogenesis is an intriguing one that has been the subject of many studies and much debate [17]–[26]. The earliest observation that H. pylori seropositivity is negatively associated with IBD [39] was not directly replicated in this study, however in our recruits undergoing concurrent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, microscopic evidence of H. pylori was entirely absent from the IBD cohort and significantly higher in normal colon controls. C. concisus is an organism that has generated significant interest following culture recovery from the colon of children with CD, with subsequent work describing the adherent, invasive and pro-inflammatory capabilities of the organism [27], [29]. Other authors have suggested that the organism may be increased in IBD against controls [28], [30], [31], yet our data contradicts this finding by demonstrating a comparable prevalence between the two groupings. Our data are the first to specifically address these organisms at the onset of IBD. The low prevalence of Helicobacteraceae and equivalent prevalence of C. concisus at the onset of IBD which we have shown makes it unlikely that these organisms have a role in disease pathogenesis in children; nevertheless their identification in the colon of subjects with established disease in other studies suggests that roles within disease chronicity may still be possible.

We have described a surprisingly diverse and prevalent colonisation of the paediatric colon with unusual Campylobacter species, including the possibility of up to three distinct species co-existing in close proximity in the same individual. The importance of these Campylobacter in paediatric health and disease warrants further consideration, particularly given the unquestionable pathogenicity of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli, the two most commonly identified representatives of the genus in paediatric faecal samples [40]. Our data suggest a more diverse and prevalent colonic colonisation with Campylobacter species than previously reported. This finding may be a direct reflection of the sampling bias introduced by studying faeces alone which is known to represent a distinct ecosystem [41]. We have shown that unusual Campylobacter species can be identified in the colon of 7/10 children and cultured successfully from 8/100. Additional studies are required to increase the culture yield for these organisms and to characterise individual species and further outline their role in health and disease.

Sutterella wadsworthensis is an organism that has rarely been discussed in the literature, having first been described as a potential gastrointestinal pathogen in 1996 [42]. We recently examined the molecular prevalence of this organism in an adult study including those with UC and those with a normal colon and found a similar and high prevalence in both groups [37]. Phenotypic and genotypic comparison of isolates suggested no difference between the two clinical groups. We suggested therefore that S. wadsworthensis is likely a common intestinal commensal. A recent paper on 32 children has however linked S. wadsworthensis to autism [43], generating considerable discussion in the process [44], [45]. We again find within the paediatric population, that this organism is commonly identified and easily recovered from biopsies by culture. Given the high prevalence (79% overall) of this organism in our whole cohort, we consider it unlikely that it is specific to the autistic intestine as has been suggested. This of course does not exclude differential immunological reaction to the organism within autistic children, which requires further exploration.

The limitations of this study cohort have been discussed previously [32] and will be repeated here briefly. All subjects received stimulant bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Although this may have altered the bacteria within the colonic mucosa, the treatment was given to all and would likely act equivalently between groups. A study where children undergo colonoscopy under general anaesthetic without bowel preparation would be unethical. The controls in this study were all children undergoing colonoscopy for gastrointestinal symptoms. There were therefore no strictly “healthy” controls. We have tried to address this by describing our subcategorisation of recruits in detail and selecting only those with a macroscopically and microscopically normal colon as our main control group.

This study rejects a role for the microaerophilic bacteria Helicobacter, Campylobacter and S. wadsworthensis at the initiation of paediatric IBD, however hypothesis-free analysis of a subgroup of the same study using pyrosequencing has shown that differences in the IBD microbiota are apparent at the onset of disease. Of particular interest to the culture results from this study, we have shown that Parabacteroides appear to be significantly reduced in UC against normal colon controls [32]. This appears to be reflected further in our culture recovery rate of Parabacteroides distasonis reported here (6 isolates derived from normal colon controls against a single UC isolate). This observation would fit with the discoveries that P. distasonis antigens can attenuate murine colitis and are specifically recognised by colonic T regulatory cells [46], [47]. P. distasonis might be suitable for consideration as a probiotic bacterium for topical colonic treatment in UC.

Conclusion

This study has provided novel data describing a hitherto unrecognised high prevalence and diversity of unusual Campylobacter species and a high prevalence of S. wadsworthensis in the paediatric colon. We have also shown a low prevalence of organisms within the Helicobacteraceae. Although we have not demonstrated any organisms of likely significance to IBD pathogenesis, we have explored two likely candidate genera specifically at the onset of disease and demonstrated that their involvement in disease initiation is unlikely. Our data on S. wadsworthensis refutes the suggestion that this organism is specific to the paediatric autistic intestine, and alongside our previous work, suggests this organism is a common intestinal commensal. Our isolates of P. distasonis from the normal paediatric colon might be suitable for consideration as probiotics. We have shown that a targeted culture and molecular microbiology study in the paediatric population can demonstrate surprising results and offer a high yield for the enumeration of unusual and rarely described organisms.

Supporting Information

PCR Primers Used in This Study.

(DOCX)

BISCUIT Patient Cohort PCR and H. pylori Serology Results for Individual Recruits with Phenotype.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Mrs Karen McIntyre was invaluable in identifying patients for recruitment in Dundee. Mrs Ann Morrice provided administrative support in Aberdeen. We appreciate the generosity of the families who freely gave their time and samples to make this study possible and the theatre staff of all centres who allowed time for sample collection during busy endoscopy lists.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by a Clinical Academic Training Fellowship from the Chief Scientist Office in Scotland (CAF/08/01) which also funded the salary of RH. The Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow IBD team is generously supported by the Catherine McEwan Foundation and the Yorkhill IBD fund. RKR is supported by an NHS Research Scotland career fellowship award. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, Aldhous MC, Round NK, et al. (2008) Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 135(4): 1114–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kugathasan S, Saubermann LJ, Smith L, Kou D, Itoh J, et al. (2007) Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 56(12): 1696–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Imielinski M, Baldassano RN, Griffiths A, Russell RK, Annese V, et al. (2009) Common variants at five new loci associated with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 41: 1335–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Henderson P, Hansen R, Cameron FL, Gerasimidis C, Rogers P, et al. (2012) Rising incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 18(6): 999–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hope B, Shahdadpuri R, Dunne C, Broderick AM, Grant T, et al. (2012) Rapid rise in incidence of Irish paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dis Child. 97(7): 590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martín-de-Carpi J, Rodríguez A, Ramos E, Jiménez S, Martínez-Gómez MJ, et al.. (2012) Increasing incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Spain (1996–2009): The SPIRIT registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, Van den Heuvel M, Van Limbergen J, et al. (2011) Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of international trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 17(1): 423–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaw SY, Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN (2010) Association between the use of antibiotics in the first year of life and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 105(12): 2687–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kronman MP, Zaoutis TE, Haynes K, Feng R, Coffin SE (2012) Antibiotic exposure and IBD development among children: A population-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 130(4): e794–e803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, et al. (2012) Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 491(7422): 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Knight R, Abubucker S, Badger JH, et al. (2012) Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 486(7402): 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, et al. (2010) A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 464(7285): 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tamboli CP, Neut C, Desreumaux P, Colombel JF (2004) Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 53(1): 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Round JL, Mazmanian SK (2009) The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 9: 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hansen R, Thomson JM, El-Omar EM, Hold GL (2010) The role of infection in the aetiology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 45(3): 266–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mukhopadhya I, Hansen R, El-Omar EM, Hold GL (2012) IBD- what role do proteobacteria play? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9(4): 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hansen R, Thomson JM, Fox JG, El-Omar EM, Hold GL (2010) Could Helicobacter organisms cause inflammatory bowel disease? FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 61(1): 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bell SJ, Chisholm SA, Owen RJ, Borriello SP, Kamm MA (2003) Evaluation of Helicobacter species in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 18(5): 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grehan M, Danon S, Lee A, Daskalopoulos G, Mitchell H (2004) Absence of mucosa-associated colonic Helicobacters in an Australian urban population. J Clin Microbiol. 42(2): 874–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bohr URM, Glasbrenner B, Primus A, Zagoura A, Wex T, et al. (2004) Identification of enterohepatic Helicobacter species in patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Microbiol. 42(6): 2766–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang L, Day A, McKenzie G, Mitchell H (2006) Nongastric Helicobacter species detected in the intestinal tract of children. J Clin Microbiol. 44(6): 2276–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Man SM, Zhang L, Day AS, Leach S, Mitchell H (2008) Detection of enterohepatic and gastric Helicobacter species in fecal specimens of children with Crohn’s disease. Helicobacter. 13(4): 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laharie D, Asencio C, Asselineau J, Bulois P, Bourreille A, et al. (2009) Association between entero-hepatic Helicobacter species and Crohn’s disease: A prospective cross-sectional study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 30(3): 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keenan JI, Beaugie CR, Jasmann B, Potter HC, Collett JA, et al. (2010) Helicobacter species in the human colon. Colorec Dis. 12(1): 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomson JM, Hansen R, Berry SH, Hope ME, Murray GI, et al. (2011) Enterohepatic Helicobacter in ulcerative colitis: Potential pathogenic entities? PLoS One. 6(2): e17184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaakoush NO, Holmes J, Octavia S, Man SM, Zhang L, et al. (2010) Detection of Helicobacteraceae in intestinal biopsies of children with Crohn’s disease. Helicobacter. 15(6): 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang L, Man SM, Day AS, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, et al. (2009) Detection and isolation of Campylobacter species other than C. jejuni from children with Crohn’s disease. J Clin Microbiol. 47(2): 453–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Man SM, Zhang L, Day AS, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, et al. (2010) Campylobacter concisus and other Campylobacter species in children with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 16(6): 1008–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Man SM, Kaakoush NO, Leach ST, Nahidi L, Lu HK, et al. (2010) Host attachment, invasion, and stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines by Campylobacter concisus and other non-Campylobacter jejuni Campylobacter species. J Infect Dis. 202(12): 1855–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mukhopadhya I, Thomson JM, Hansen R, Berry SH, El-Omar EM, et al. (2011) Detection of Campylobacter concisus and other Campylobacter species in colonic biopsies from adults with ulcerative colitis. PLoS One. 6(6): e21490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahendran V, Riordan SM, Grimm MC, Tran TA, Major J, et al. (2011) Prevalence of Campylobacter species in adult Crohn’s disease and the preferential colonization sites of Campylobacter species in the human intestine. PLoS One. 6(9): e25417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansen R, Russell RK, Reiff C, Louis P, McIntosh F, et al. (2012) Microbiota of de-novo pediatric IBD: Increased Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and reduced bacterial diversity in Crohn’s but not ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 107(12): 1913–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lennard-Jones JE (1989) Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 24(S170): 2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. IBD Working Group of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (2005) Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: Recommendations for diagnosis- the porto criteria. JPGN. 41(1): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, et al.. (2005) Towards an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal world congress of gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 19(Suppl A): 5A–36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, et al.. (2011) Pediatric modification of the montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: The Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1314–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mukhopadhya I, Hansen R, Nicholl CE, Alhaidan Y A, Thomson JM, et al. (2011) A comprehensive evaluation of colonic mucosal isolates of Sutterella wadsworthensis from inflammatory bowel disease. PloS ONE. 6(10): e27076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hold GL, Pryde SE, Russell VJ, Furrie E, Flint HJ (2002) Assessment of microbial diversity in human colonic samples by 16S rDNA sequence analysis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 39(1): 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. El-Omar E, Penman I, Cruikshank G, Dover S, Banerjee S, et al. (1994) Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in inflammatory bowel disease: Association with sulphasalazine. Gut. 35(10): 1385–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lastovica AJ (2000) Efficient isolation of Campylobacteria from stools. J Clin Microbiol. 38(7): 2798–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, et al. (2005) Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 308(5728): 1635–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wexler HM, Reeves D, Summanen PH, Molitoris E, McTeague M, et al. (1996) Sutterella wadsworthensis gen. nov., sp. nov., bile-resistant microaerophilic campylobacter gracilis-like clinical isolates. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 46(1): 252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williams BL, Hornig M, Parekh T, Lipkin WI (2012) Application of novel PCR-based methods for detection, quantitation, and phylogenetic characterization of Sutterella species in intestinal biopsy samples from children with autism and gastrointestinal disturbances. MBio. 3(1): e00261–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Benach JL, Li E, McGovern MM (2012) A microbial association with autism. MBio. 3(1): e00019–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Collins SM, Surette M, Bercik P (2012) The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 10(11): 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kverka M, Zakostelska Z, Klimesova K, Sokol D, Hudcovic T, et al. (2011) Oral administration of Parabacteroides distasonis antigens attenuates experimental murine colitis through modulation of immunity and microbiota composition. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 163(2): 250–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio CW, et al. (2011) Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 478(7368): 250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fox JG, Dewhirst FE, Shen Z, Feng Y, Taylor NS, et al. (1998) Hepatic Helicobacter species identified in bile and gallbladder tissue from Chileans with chronic cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 114(4): 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grehan M, Tamotia G, Robertson B, Mitchell H (2002) Detection of Helicobacter colonization of the murine lower bowel by genus-specific PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 68(10): 5164–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Linton D, Owen R, Stanley J (1996) Rapid identification by PCR of the genus Campylobacter and of five Campylobacter species enteropathogenic for man and animals. Res Microbiol. 147(9): 707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PCR Primers Used in This Study.

(DOCX)

BISCUIT Patient Cohort PCR and H. pylori Serology Results for Individual Recruits with Phenotype.

(DOCX)