Abstract

The crystal structure of Ta0880, determined at 1.91 A resolution, from Thermoplasma acidophilum revealed a dimer with each monomer composed of an α/β /α sandwich domain and a smaller lid domain. The overall fold belongs to the PfkB family of carbohydrate kinases (a family member of the Ribokinase clan) which include ribokinases, 1-phosphofructokinases, 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase, inosine/guanosine kinases, frutokinases, adenosine kinases, and many more. Based on its general fold, Ta0880 had been annotated as a ribokinase-like protein. Using a coupled pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase assay, the activity of Ta0880 was assessed against a variety of ribokinase/pfkB-like family substrates; activity was not observed for ribose, fructose-1-phosphate, or fructose-6-phosphate. Based on structural similarity with nucleoside kinases (NK) from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (MjNK, PDB 2C49 and 2C4E) and Burkholderia thailandensis (BtNK, PDB 3B1O), nucleoside kinase activity was investigated. Ta0880 (TaNK) was confirmed to have nucleoside kinase activity with an apparent KM for guanosine of 0.21 μM and catalytic efficiency of 345,000 M−1 s−1. These three NKs have significantly different substrate, phosphate donor, and cation specificities and comparisons of specificity and structure identified residues likely responsible for the nucleoside substrate selectivity. Phylogenetic analysis identified three clusters within the PfkB family and indicates that TaNK represents a new sub-family with broad nucleoside specificities.

Keywords: ribokinase, PfkB-like superfamily, kinetics, structure-function relationship, nucleoside kinase

Introduction

Nucleoside kinases (NKs) belong to the phosphofructokinase B (PFK-B) family (Pfam PF00294), which is part of the ribokinase (RK)-like superfamily (Pfam CL0118). NKs catalyze the phosphorylation of a variety of nucleosides to the corresponding nucleoside 5Prime;-monophosphate in the presence of phosphate donors and divalent cations. In bacteria, nucleoside kinases are thought to play a minor role in the purine synthesis salvage pathway with the major contribution thought to be from nucleoside phosphorylases and deaminases.1 For pyrimidine biosynthesis, the kinases play a more significant role in the salvage pathway. However, these broad specificity nucleoside kinases are not well characterized and their role in purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis (compared to specific nucleoside kinases) is unknown.1–3 NKs from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii2 (MjNK; GI: 1592288, UniProt: Q57849), Burkholderia thailandensis3 (BtNK; GI: 83654474, UniProt: Q2SZE4), and Aeropyrum pernix2,4 (ApPFK; GI: 118430835, UniProt: Q9YG89) have been identified and functionally characterized. Both MjNK and BtNK are classified as NKs because they catalyze the phosphorylation of both purine and pyrimidine nucleosides but do not phosphorylate sugar substrates.2,3 ApPFK phosphorylates fructose-6-phosphate in addition to nucleosides2. While the structures of two NKs (MjNK, PDB: 2C49 and BtNK, PDB: 3B1O) were determined in complex with phosphate donors and substrates5,6 and some insight to substrate specificity of the NK family has been proposed, the limited biochemical and structural data has hindered the identification of a nucleoside substrate binding motif that separates the family from the other sugar kinases of the PFK-B family.

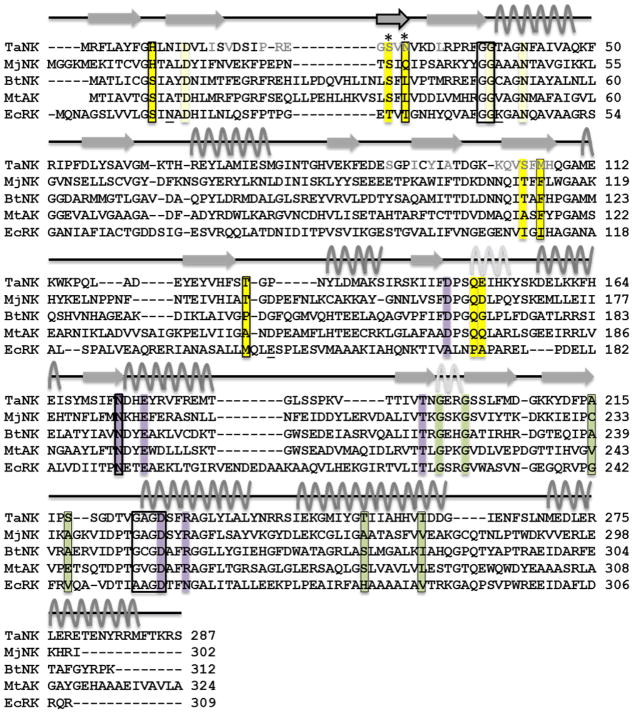

The structure of Ta0880 from Thermoplasma acidophilum was determined to 1.91 A resolution and reveals a dimer with each monomer composed of an α/β /α sandwich domain and a smaller lid domain. Ta0880 contains consensus substrate, cofactor, and divalent cation binding motifs characteristic of the ribokinase-like superfamily (Fig. 1)3: a glycine-glycine dipeptide (G37 and G38 in Ta0880), which plays a role in the closed conformation of the enzyme and in substrate sequestration7; the NXXE (N173-E176 in Ta0880) sequence for binding Mg2+ and ATP; and an anion-hole motif (G225-D228 in Ta0880) which neutralizes negative charge accumulated during the phosphate group transfer.3,5 Residues that differentiate substrate specificity between the nucleoside and sugar kinases are not well understood. Sequence and structural similarity to MjNk (PDB: 2C4E, rmsd 2.44 A) indicate that Ta0880 is likely a nucleoside kinase.

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of TaNK, MjNK, BtNK, and MtAK, and EcRK. Secondary elements are indicated by arrows (β-strands), gray curvy lines (α-helices), light gray curvy lines (310 helices), and straight lines (loops); the swapped β-stand is indicated with a black outline. Residues involved in the TaNK dimer interface are colored in light gray font. Residues involved in substrate binding are highlighted pale yellow (ribose interactions) or yellow (base interactions); phosphate donor binding, green; Mg2+ coordination, purple; and unconserved residues within these categories are boxed with a thin line. Regions boxed with a thick line correspond to the three characteristic motifs: the glycine-glycine dipeptide sequence (G37, G38 in TaNK), the NXXE motif (N173-E176 in TaNK), and the anion-hole motif (G225-D228 in TaNK). The asterisks indicate residues involved in the binding site that are contributed by the other subunit. Conserved residues in ribokinases are underlined.

In this study, Ta0880 is shown to be a NK (called TaNK hereafter) with broad substrate, phosphate donor, and metal cofactor specificity. Kinetic parameters were determined for a variety of substrates, metals, and phosphate donors and compared to two other characterized nucleoside kinases, MjNK and BtNK. Residues important to nucleoside binding were identified by comparing the structures, substrate specificity and enzymatic turnover of these enzymes. In addition, phylogenetic analysis indicates that NK sequences are clustered independently from the ribokinase and adenosine kinase PFK-B subfamilies, and define a new subfamily with broad nucleoside specificities.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression and purification for crystallization

The TaNK (Ta0880) expression clone from Thermoplasma acidophilum ((strain ATCC 25905/DSM 1728; Uniprot: Q9HJT3; GenBank: NC_002578; GI: 16081186) was generated using the polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) cloning method.8 The gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from genomic DNA using PfuTurbo DNA Polymerase (Stratagene) and I-PIPE (Insert) primers that included the predicted 5Prime; and 3Prime; ends. The expression vector, pSpeedET, which encodes an amino-terminal tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease-cleavable expression and purification tag (MGSDKIHHHHHHENLYFQ/G), was PCR amplified with V-PIPE (Vector) primers. V-PIPE and I-PIPE PCR products were mixed to anneal the amplified DNA fragments together. Escherichia coli GeneHogs (Invitrogen) competent cells were transformed with the I-PIPE / V-PIPE mixture and dispensed on selective LB-agar plates. Three mutations were subsequently introduced (E112A, K113A, and K115A) using the PIPE method to improve crystallization.9 Expression was performed in a selenomethionine-containing medium at 37 C with suppression of normal methionine synthesis.10 At the end of fermentation, lysozyme was added to the culture to a final concentration of 250 μg/mL, and the cells were harvested and frozen. After one freeze/thaw cycle, the cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine-HCl (TCEP)) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 32,500g for 30 min. The soluble fraction was passed over nickel-chelating resin (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer and the resin washed with wash buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP). The protein was eluted with elution buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 300 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP). The elulate was buffer exchanged into HEPES crystallization buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP) and concentrated for crystallization trials to 19 mg/mL by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined using the Coomassie Plus assay (Pierce).

Crystallization

Proteins were crystallized using the nanodroplet vapor diffusion method11 with standard JCSG crystallization protocols.9,12 Crystals were grown using sitting drops composed of 200 nL protein solution mixed with 200 nL of crystallization solution and equilibrated against a 50 μL reservoir at 277 K for up to 30 days before harvesting. The crystallization reagent was composed of 40% 1,2-propanediol and 0.1 M acetate (pH 4.5). Initial screening for diffraction was carried out using the Stanford Automated Mounting system (SAM)13 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Menlo Park, CA). The diffraction data were indexed in orthorhombic space group P212121.

Data collection, structure solution, and refinement

Three-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data were collected at 23-ID-D beamline (GM/CA CAT) at APS from a single crystal at wavelengths corresponding to the inflection (λ1=0.97953 A), remote (λ2=0.91840 A), and peak (λ3=0.97939 A) of the selenium K absorption edge. The dataset was collected at 100 K with a MarCCD 300 detector (Rayonix) using the JBluIce-EPICS14 data collection software. The data processing and structure solution were carried out using an automatic structure solution pipeline developed at the JCSG.15 The data were integrated and reduced using XDS and scaled with the program XSCALE.16–18 Phasing was performed with SOLVE19 which resulted in a mean figure of merit of 0.38 with 26 selenium sites. Phase refinement and automatic model building were performed using RESOLVE20. Model completion and refinement were performed with COOT21 and REFMAC522. CCP4 programs were used for other calculations and data manipulation.23 Data reduction and refinement statistics are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Summary of crystal parameters, data collection, and refinement statistics for TaNK (PDB code 3BF5). Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Space group | P 21 21 21 | ||

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a =56.45 b=59.18, c = 177.65 | ||

| Data collection | λ1 MAD-Se (Inflection) | λ2 MAD-Se(Remote) | λ3 MAD-Se(Peak) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97953 | 0.91840 | 0.97939 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.1–2.04 (2.11–2.04) | 29.2–1.91 (1.98–1.91) | 29.3–2.04 (2.11–2.04) |

| No. observations | 116,130 | 141,343 | 115,246 |

| No.unique reflections | 38,509 | 46,740 | 38,415 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.6 (99.6) | 98.4 (99.6) | 97.7 (99.7) |

| Mean I/σ (I) | 7.52 (1.09) | 10.78 (1.37) | 6.98 (1.07) |

| Rmerge †(%) | 7.6(84.4) | 5.0 (68.5) | 8.4 (89.5) |

| Rmeas ‡ (%) | 10.0(109.6) | 6.6 (89.4) | 11.0 (116.6) |

| Model and refinement statistics | |||

| Data set used in refinement(|F|>0) | λ2 | ||

| No. reflections (total) | 46,708§ | ||

| No. reflections (test) | 2364 | ||

| Completeness (%) | 99.1 | ||

| Rcryst¶ | 0.202 | ||

| Rfree¶ | 0.245 | ||

| Restraints (r.m.s.d. observed) | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.596 | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | ||

| Average isotropic B value†† (Å 2) | 34.3 | ||

| (protein residues/solvent) | 42.2/51.6 | ||

| ESU‡‡ based on Rfree (Å) | 0.155 | ||

| Protein residues/atoms | 563 / 4,419 | ||

| Waters/solvent molecules | 214 (waters)/ 8 (solvent) | ||

Rmerge = ΣhklΣi|Ii(hkl) − (I(hkl))|/Σhkl Σi(hkl).

Rmeas = Σhkl[N/(N − 1)]1/2Σi|Ii(hkl) − (I(hkl))|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl) 74.

Typically, the number of unique reflections used in refinement is slightly less than the total number that were integrated and scaled. Reflections are excluded owing to negative intensities and rounding errors in the resolution limits and unit-cell parameters.

Rcryst = Σhkl||Fobs| −|Fcalc||/Σhkl|Fobs|, where Fcalc and Fobs are the calculated and observed structure-factor amplitudes, respectively. Rfree is the same as Rcryst but for 4.9% of the total reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

This value represents the total B that includes TLS and residual B components.

Estimated overall coordinate error 75,76

Structure validation and deposition

The quality of the crystal structures was analyzed using the JCSG Quality Control server (http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/jcsg/QC). This server analyses the data using a variety of validation tools including AutoDepInputTool24, MolProbity25, WHATIF 5.0.26, and RESOLVE27. Protein quaternary structure analysis was performed using the PISA server.28 Molecular graphic figures were prepared with PyMOL (Ver.1.3, Schrodinger, LLC.). Atomic coordinates and experimental structure factors for TaNK at 1.91 A resolution have been deposited in the PDB and are accessible under PDB ID: 3BF5.

Sequence and structural alignments, ligand modeling, and phylogenetic analysis

Sequence alignments were generated using ClustalW and manually adjusted based on the structural alignment. Structural alignments were performed with DaliLite29,30 or PyMOL (Ver.1.3, Schrodinger, LLC.). A structural alignment of the open conformations of TaNK, MjNk, and BtNK indicated that the overall fold and lid conformation was similar in all three structures. In addition, the ligand-based active site alignment31 of the nucleoside-bound structures of MtNK (adenosine), MjNK (adenosine), and BtNK (inosine) indicated the bound conformations were similar in terms of the positioning of the equivalent amino acids in the active sites. Thus, a model of the TaNK closed (ligand bound) conformation was generated using SWISS-MODEL32,33 and the nucleoside-bound structure of MjNK (2C49) as the template. The interactions that each nucleoside would make were assessed using the ligand-based active site alignment for which the ribose and purine of each nucleoside were aligned (alignment of the inosine and two adenosines was used to position the modeled guanosine).

For phylogenetic analysis, a set of 21 nucleoside and sugar kinases were selected based on functional characterization in the literature. The 21 protein sequences (Table S1) were obtained from UniProtKB34,35 and submitted to the Phylogeny.fr server.36

Expression and purification for activity assays

A pSpeedET vector encoding the recombinant TaNK protein with the N-terminal histidine tag was transformed into the DH10B derived E. coli expression cell line HK100 and selected for on Luria broth agar plates containing ampicillin. During log phase growth, gene expression was induced with 0.02% arabinose for four hours. The cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed in 50 mM Tris pH 8 and 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.5 mg/mL lysozyme (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.04 μL/mL Benzonase nuclease (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ). A cleared cell lysate containing the soluble protein was obtained by centrifugation and loaded on an immobilized metal affinity chromatography resin (GE Healthcare) charged with 100 mM CoCl2. The resin was washed with 15 mL low imidazole wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) and bound protein was eluted with 10 mL elution buffer (wash buffer supplemented to 450 mM imidazole). Purification was followed by SDS-PAGE analysis of the flow-through, wash, and elution fractions. The purified TaNK migrated as a ~33 kDa protein, in good agreement with the calculated molecular mass of 32,804 Da. The elution fractions were pooled and then dialyzed three times into 500 mL of buffer (100 mM Tris pH 8,0 and 150 mM KCl) over eight hours at room temperature. Protein concentration was determined using absorbance at 280 nm and the molar extinction coefficient of 27,850 M−1cm−1 (calculated with ProtParam37).

Kinetics assays and determination of kinetic parameters

The catalytic activity of TaNK was determined spectrophotometrically on a Beckman-Coulter DU-800 spectrophotometer at 340 nm using a coupled enzyme assay with pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase (PK/LDH) as described previously2. Unless stated otherwise, assays were performed at 22° C with saturating substrate concentrations (5 mM) in reaction mixtures containing 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1.3 mM magnesium sulfate, 4.6 mM KCl, 1 mM phospho(enol) pyruvate, 1.3 mM ATP, 0.14 mM NADH, 13.3 μL PK/LDH (12–19 units PK with 8–13 units LDH) (all purchased from Sigma), and 1 μM TaNK. Assays were performed at 22° C because at higher temperature the activity of the coupling enzymes (PK/LDH) is rate limiting (data not shown). Coupled reactions were carried out in 1.0 mL volumes with TaNK protein added last. Reaction samples were mixed immediately after addition of TaNK and the change in absorbance at 340 nm was measured over 40 seconds. During the pyruvate kinase coupled reaction, the ADP product of the TaNK reaction is phosphorylated to regenerate ATP while phospho(enol) pyruvate is converted to pyruvate. Lactate dehydrogenase then converts that pyruvate product to lactate while the NADH cofactor is oxidized to NAD+. NADH has an absorbance maximum at 340 nm whereas NAD+ absorbs weakly. The change in NADH concentration was calculated using the extinction coefficient of NADH (6,220 M−1cm−1) at 340 nm. The change in NADH concentration is directly proportional to product formation by TaNK.

Substrate specificity was examined with 1.5 mM guanosine, inosine, cytidine, adenosine, thymidine, uridine, and 2-deoxy adenosine or 5 mM ribose, fructose-1-phosphate, and fructose-6-phosphate (Sigma) as substrates. Cation specificity was studied by replacing the 1.3 mM Mg2+ with equimolar Co2+, Ni 2+, or Mn2+. Phosphate donor specificity was examined by exchanging 1.3 mM ATP in the assay mixture with GTP, ITP, TTP, and UTP (Sigma) at equimolar concentrations.

pH dependence of Ta0880 nucleoside activity

The pH dependency of TaNK was investigated with inosine (the nucleoside with the highest Vmax) as the substrate at pH values from 5.5 to 8. Tris buffer in the standard assay conditions was substituted with 100 mM phosphate buffer to ensure buffering over the entire pH range investigated.

Results

Overall structure and functional classification

The crystal structure of TaNK was determined in space group P212121 at 1.91 A resolution using the MAD method (PDB: 3BF5). Data collection, model, and refinement statistics are summarized in Table I. The final model of TaNK includes two protein monomers (residues 8–293), one phosphate ion, seven 1,2-propanediol molecules (from the crystallization condition), and 214 water molecules in the asymmetric unit. Due to the lack of interpretable electron density, residues -18 to -1 (the expression and purification tag), and 284–287 of chain A and residues -18 to 0, 264 – 266, and 283–287, of chain B were omitted from the model. In addition, 14 surface side chains in chain A and 26 in chain B were only partially modeled. The Matthews’ coefficient (Vm)38 for TaNK is 2.08 A3/Da, and the estimated solvent content is 40.9%. MolProbity39 calculated 97.0% of the residues are in favored regions with no outliers in the Ramachandran plot.

TaNK consists of 14 β-strands (β1- β14), nine α-helices (α1-α9), and two 310-helices (H3/101 and H3/102; Fig. 1 and 2). Analysis of the crystallographic packing using the PISA server28 suggests that the dimer, as observed in the crystal structure and confirmed by size exclusion chromatography and static light scattering experiments, is the biological oligomeric state. Each monomer is composed of an α/β/α sandwich domain and a smaller lid domain for which a single β-strand (β3) is swapped between the monomers. Much of the dimer interface is mediated by the lid domain (Fig. 1 and 2); specifically residues in β2 – 4, β7, and β8 (residues in light gray font in Fig. 1). Based on sequence and overall fold, TaNK belongs to the carbohydrate kinase (ribokinase-like) pfkB family. Structures that share significant similarity to TaNK and have been functionally characterized include human ribokinase40 (PDB: 2FV7; Z-score 27.1 and rmsd 2.4 A), adenosine kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis41,42 (MtAK; PDB: 2PKF; Z-score 30.2 and rmsd 3.1 A), nucleoside kinase from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii2,5 (MjNK; PDB: 2C4E; Z-score 31.2 and rmsd 2.3 A), E. coli ribokinase40,43 (EcRK; PDB: 1RKA; Z-score 26.5 and rmsd 2.8 A), nucleoside kinase from Burkholderia thailandensis3,6 (BtNK; PDB: 3B1O; Z-score 30.8 and rmsd 2.9 A), and human ketohexokinase44 (PDB: 3QA2; Z-score 25.2 and rmsd 2.7 A). All of these proteins are dimeric and have a similar overall fold (Cα rmsd from 1.7 A (MjNK) to 4.0 A (E. coli ribokinase) with TaNK). Although the dimer interfaces are structurally similar, the residues at the dimeric interface are not conserved (Fig. 1). Based on these global analyses, the function originally assigned to TaNK was ribokinase-related protein (some databases have ribokinase and sugar kinase annotations (e.g. KEGG and eggNOG)). The enzymatic activity (i.e. specific substrate) could not be confidently predicted from sequence or fold comparison although the highest structural similarity suggested TaNK may be a nucleoside kinase.

Figure 2.

Structure of TaNK. (A) Ribbon diagram of the TaNK dimer (subunits colored gray and orange). The TaNK monomer has 14 β-strands (β1- β14), nine α-helices (α1-α9), and two 310- helices (H3/101 and H3/102). One of the β-strands (β3) is swapped between the monomers. (B) The NKs are homodimers (MjNK; rendered with a semi-transparent surface and the backbone as a cartoon and the subunits are colored dark and light gray) that bind a phosphate-donor (e.g. ATP), a divalent cation (e.g. Mg2+), and a nucleoside substrate (e.g. adenosine).

Substrate specificity

The specificity of the substrate, phosphate donor, and cation were investigated under saturating conditions using a coupled assay to PK/LDH. Although the activity of the PK coupling enzyme requires a cation and phosphate donor/acceptor, the PK enzyme has a broad range specificity for phosphate acceptors45–47 and cations47,48, allowing the specificity of TaNK to be investigated. With Mg2+ and ATP as a phosphate donor, TaNK activity was determined using sugars, sugar-phosphates, and nucleosides (Fig. 3A) as substrates. In the presence of ribose, fructose-1-phosphate, and fructose-6-phosphate, TaNK kinase activity was not detected (data not shown). Significant kinase activity was observed in the presence of nucleosides; the highest activity (in terms of catalytic efficiency) was observed with guanosine, followed by inosine, cytidine, and adenosine (Table II). Negligible TaNK enzymatic activity was detected with thymidine, uridine, and 2-deoxyadenosine (data not shown).

Figure 3.

TaNK nucleoside kinase activity. (A) TaNK Activity was demonstrated with inosine, guanosine, cytidine and adenosine as phosphate acceptor substrates. (B) TaNK activity was tested with ATP, GTP, ITP, TTP, and UTP as phosphate donors. (C) TaNK activity was modulated by the presence of various metal ions: Mn 2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, and Co2+. (D) Michaelis- Menten plots of TaNK activity with varying ATP (◆) and GTP (■) concentrations. Data points are averages of three replicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

Table II.

Substrate specificity of nucleoside kinase Ta0880 from Thermoplasma acidophilum

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Apparent KM (μM) | Catalytic efficiency kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | Catalytic efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guanosine | 7.19 (± 0.45)a × 10−2 | 0.208 (± 0.110) | 345,000 (± 58,000) | 100 |

| Inosine | 1.60 (± 0.10) × 10−1 | 0.712 (± 0.200) | 215,000 (± 48,000) | 62 |

| Cytidine | 6.44 (± 0.31) × 10−2 | 0.411 (± 0.100) | 156,000 (± 40,000) | 45 |

| Adenosine | 8.40 (± 0.01) × 10−2 | 1.12 (± 0.150) | 74,900 (± 8,000) | 22 |

| ATP | 1.74 (± 0.03) × 10−1 | 46.9 (± 2.00) | 3,700 (± 100) | 100 |

| GTP | 2.66 (± 0.27) × 10−1 | 185 (± 26.0) | 1,440 (± 84.0) | 39 |

values in parentheses are standard deviations of three replicates

With the Mg2+ cation and inosine as a substrate, the phosphate donor specificity was explored by examining TaNK enzymatic activity with ATP, GTP, UTP, TTP, or ITP at 1.3 mM each. GTP yielded the highest activity (Fig. 3B and Table II); ATP and ITP were capable of donating a phosphate, but with much less efficiency than that of GTP. Negligible enzymatic activity was observed with UTP and TTP as phosphate donors.

Nucleoside kinase activity has been shown to require the presence of divalent cations2,3,49; thus, the cation specificity of TaNK was determined (Fig. 3C). TaNK kinase activity was observed with Mg2+ and Co2+ and to a lesser degree with Mn2+ (Fig. 3C); nucleoside activity was not observed with Ni2+ as a divalent cation. The concentration of metal was more than a thousand times higher than the TaNK concentration, which would saturate the His-tag as well as the catalytic binding site.

Kinetic parameters of TaNK

All substrates and phosphate donors followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 3D and 4A). TaNK showed the highest affinity (assuming k−1 ≫> kcat) for guanosine (apparent Km value 0.208 μM) followed by cytosine, inosine, and adenosine with apparent Km values of 0.411, 0.712, and 1.12 μM, respectively (Table II). The highest kcat observed was with inosine as a substrate (0.160 s−1), followed by adenosine, guanosine, and cytidine (Table II). The highest catalytic efficiency was observed with guanosine at 345,000 M−1 s−1 (100%), followed by inosine (62%), cytidine (45%), and adenosine (22%). The kcat and apparent Km values for ATP, measured with inosine as the substrate, were 0.174 s−1 and 46.9 μM , respectively. In comparison GTP had kcat and apparent Km values of 0.266 s−1 and 185 μM (Fig. 3D and Table II), respectively. The catalytic efficiency of GTP was approximately 40% that of ATP.

Figure 4.

TaNK nucleoside kinase kinetic parameters: (A) Michaelis-Menten and (B) Hanes-Woolf plots with phosphate acceptor substrates adenosine (●), inosine (◆), guanosine (□), and cytidine (Δ). Data points are averages of three replicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

pH dependence

The pH dependence of TaNK could be investigated because the coupling enzymes PK and LDH do not have a strong pH dependency over the range tested.50–52 TaNK shows optimal enzymatic activity at pH 6.6; however, significant activity was observed over the pH range of 6.4 to 7.8 (Fig. 5), Enzymatic activity decreased markedly at pH 8 and at pH 6.2 and below. Though T. acidophilum is found in low pH environments53; the cytoplasmic pH is maintained at near-neutral over an extracellular pH range of 2 – 5,54,55 consistent with the observed TaNK activity dependence on pH.

Figure 5.

The pH dependency of TaNK. TaNK shows optimal inosine kinase activity at pH 6.6 and significant activity from pH 6.4 to 7.8. Activity dramatically decreases at pH values less than 6.4 and above 7.8. Data points are averages of three replicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

Discussion

TaNK forms a dimer that has a single domain swapped β-strand in the lid domain (Fig. 2). The structure is highly similar to ribokinases and other members of the PFK-B family. A multiple sequence alignment of TaNK with characterized nucleoside kinase PFK-B family (MjNK and MtAK) and RK from E. coli3,41,43 (Fig. 1) shows that the three consensus motifs (GG, NXXE, and the anion-hole GA/VGD; boxed in Fig. 1) found in the RK-like superfamily and the PFK-B family are conserved. One of these motifs found in the RK-like superfamily is the glycine-glycine dipeptide sequence (G37, G38 in TaNK)56, which is proposed to play an important role in the formation of the closed conformation of the enzyme and in substrate sequestration.57 The NXXE motif (N173-E176 in TaNK) is highly conserved in the RK-like superfamily and has been identified as important for both cation and ATP binding.56 The most highly conserved region among the superfamily members is the anion-hole motif (G225-D228 in TaNK), which helps to neutralize negative charges during phosphate group transfer.3 Although TaNK was originally annotated as a ribokinase, two of the residues commonly found in ribokinases are absent in TaNK (K43 and E143 in the RK from E. coli [underlined in Fig. 1]). These two residues interact with the C1 hydroxy group of ribose43, a group that is not present in the nucleoside due to the formation of the glycosidic bond with the base. Comparison of ribokinases to adenosine kinases indicates that the residues in RKs that favor ribose binding over adenosine are I112, N14, and E143 (E. coli RK [underlined in Fig. 1]); these residues are alanine, leucine, and phenylalanine, respectively, in AKs56 and are not conserved between the RKs, AKs and NKs. Additionally, the oligomeric state is not conserved between the adenosine kinases and ribo/nucleoside kinases: AKs are monomeric and RKs and NKs are dimeric.56

Metal specificity

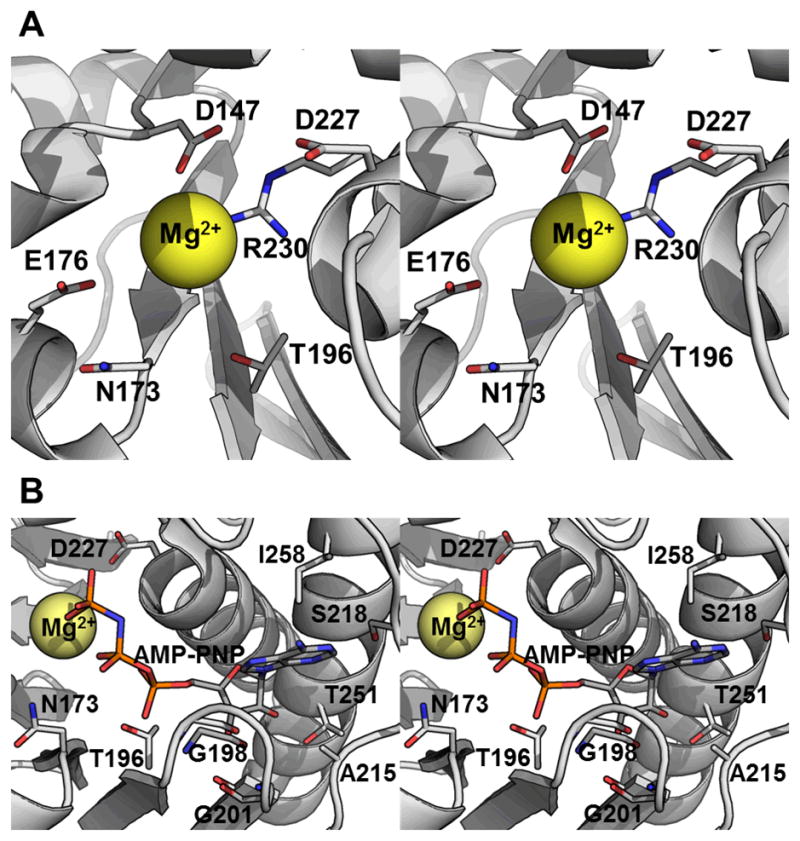

The Mg2+ ion in the MjNK, (PDB: 2C49) and BtNK (PDB: 3B1R) structures exhibit octahedral coordination with six water molecules, that interact with six conserved residues. These residues are also conserved in TaNK (Fig. 6A; waters not shown). Residues E176, N173 and D227 comprise a conserved motif in ribokinases (boxed in thicker lines in Fig. 1 and additional sequences in Fig. S1). T196 is also conserved between the RKs and NKs (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1) although it is not included in the defined motif. The remaining residues, D147 and R230, are conserved among the NKs, but not with the RKs. Therefore, the differences in metal specificity between the NKs (most notably the higher catalytic activity TaNK has with Co2+ (Table III)) are not due to differences in the direct interactions with the metal.

Figure 6.

Cation coordination and phosphate donor interactions. (A) Cation binding site (stereo image). (B) Phosphate donor binding site (stereo image). The backbone of TaNK is rendered as a cartoon and the side chains involved are shown and labeled. These figures were generated by structurally aligning TaNK using DaliLite29 with the adenosine-Mg2+-AMP-PNP complexed MjNK structure (PDB ID 2C49). The residues are labeled according to the TaNK sequence (Fig. 1).

Table III.

Comparison of the biochemical and kinetic properties of nucleoside kinases from Thermoplasma acidophilum, Burkholderia thailandensis, and Methanocaldococcus jannasschii.

| Value

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Property | TaNK | BtNK3 | MjNK2 |

| pH Optimum | 6.6 | 5.5–6.5 | 7.0 |

| Apparent * Km (μM) | 0.208 | 150‡ | 25† |

| Catalytic efficiency* (kcat/Km) (M−1 s−1) | 345,000 | 80,000 | 37,500§ |

| Substrate specificity (catalytic efficiency) | guanosine> inosine≫ cytidine>adenosine# | inosine> adenosine# | inosine> cytidine≫ guanosine# |

| Phosphoryl donor specificity (% of Vmax) | GTP> ATP> ITP> TTP, UTP | ITP> TTP, GTP> ATP> CTP, UTP | ATP ≫ ITP, GTP> UTP> CTP |

| Cation specificity (% of Vmax) | Mg2+, Co2+> Mn2+> Ni2+ | Mn2+> Mg2+> Ni2+, Co2+ | Mg2+, Mn2+> Ni2+> Co2+ |

| PDB ID | 3BF5 | 3B1Q, 3B1N, 3B1P, 3B1R and 3B1O | 2C49 and 2C4E |

| Uniprot Accession | Q9HJT3 | Q2SZE4 | Q57849 |

The kinetic parameter of the first substrate found in the substrate specificity row below

Reported as Vmax/kcat

Determined at 70° C in a discontinuous assay coupled to pyruvate kinase lactate dehydrogenase.2

Determined at 37° C by measuring the formation of NADH in a coupled reaction that consisted of two enzymatic reactions: (a) BthNK dependent phosphorylation of inosine to IMP with the dephosphorization of ATP to ADP, and (b) oxidation of IMP to xanthosine 5′:-monophosphate with reduction of NAD to NADH by IMP dehydrogenase.3

Additional substrates that showed less than 1% of the activity observed for the substrate with the highest catalytic efficiency are thymidine, uridine, 2-deoxy adenosine, ribose, fructose-1-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate for TaNK; guanosine, mizoribine, 2-deoxy-adenosine, uridine, ribavirin for BtNK; and adenosine, ribose, uridine, 2-deoxy-adenosine, thymidine for MjNK.

Phosphate donor specificity

Each NK has unique phosphate donor preferences: BtNK prefers ITP, TTP, and GTP, with 2.0, 1.3, and 1.2 fold greater activity (percent of Vmax) than ATP, respectively3; MjNK has the highest Vmax with ATP, < 50% with ITP or GTP, and < 10 % with UTP or CTP2; and TaNK has the highest Vmax with GTP, < 60% with ATP, < 50% with ITP, and < 20% with UTP and TTP (Table III). Four residues in TaNK that presumably interact with the base of the phosphate donor are A215, S218, T251 and I258 (Fig. 6B). These residues are not conserved between the three enzymes and may account for the different phosphate donor specificities. However, further comparison is difficult because percent Vmax is not a good measure of specificity (kcat is not reported for MjNK and BtNK), as exemplified by comparing ATP and GTP for TaNK. Although GTP has the higher Vmax (0.266 μM s−1), the catalytic efficiency of TaNK is significantly higher for ATP (Table III).

Nucleoside specificity

Nucleoside kinase activity was demonstrated for TaNK for a variety of nucleoside substrates, while sugar kinase activity was not observed. In comparison to the other known nucleoside kinases, this broad substrate specificity for nucleosides, but not for sugars, has only been reported for two other proteins: BtNK and MjNK. The broad nucleoside specificity is interesting in light of the other more specific PFK-B family enzymes. Adenosine kinases (AK) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis41, Saccharomyces cervisiae58, and Toxoplasma gondii59 were reported as having only adenosine kinase activity. The structure and biochemistry of MtAK is unique compared to the mammalian AKs and is structurally more similar to the NKs. Another PFK-B nucleoside kinase specific family is the inosine-guanosine kinases (INGKs). These enzymes can show specificity between inosine and guanosine and also demonstrate activity with other nucleosides (albeit to a lesser extent). Previously described enzymes with relatively broad substrate specificities include E. coli INGK60, human AK61, MjNK, and BtNK. Other nucleoside kinases, such as uridine-cytidine and thymidinie kinases, are not members of the PFK-B family and are structurally distinct compared to the adenosine and inosine-guanosine kinases. However, TaNK and MjNK2 are the only members of the PFK-B family of enzymes with reported cytidine kinase activity.

A comparison of the structures and substrate specificities of nucleoside kinases (TaNK, BtNK, and MjNK) (Table III) and MtAK provides some insight into the differences in specificity. Comparison of the available apo and bound PFK-B nucleoside kinase structures indicate that the TaNK lid domain (Fig. 2) exists in an open conformation that closes upon substrate binding.5,6 Although the TaNK structure does not have substrate or phosphate donor bound and is in the open conformation, conclusions can be drawn based on comparison (and modeling) to MjNK (adenosine)5, BtNK (inosine)6, and MtAK (adenosine)42 bound (closed) structures for which the open conformations are structurally very similar to TaNK. After modeling TaNK using the adenosine-bound closed state of MjNK, a ligand-based active site alignment of the four nucleoside-bound structures provided a comparison of the residues important in interacting with nucleoside phosphate acceptor. All four proteins have three conserved residues that interact with the ribose of the nucleoside (D13, N42, and D227 in TaNK); these residues do not interact with the base moiety and, therefore, do not account for substrate specificity. In terms of the base specificity, a few trends are observed: all three NKs have inosine specificity; TaNK and MjNK have guanosine and cytidine specificity, and, for comparison.

The interactions with the nucleoside base can be classified on the basis of orientation of the base in the binding pocket. There are two residues that interact above and below the plane of the purine rings: Q150 in TaNK is conserved in MtNK, MjNK, and BtNK and M106 is replaced with phenylalanine in MtNK, MjNK, and BtNK (Fig. 7 and 8). The three purines differ at positions C6, N1, and C2. Functional groups at C6 (carbonyl or amino groups) and N1 interact with the lid domain (residues S26*, N28*, and S104 in TaNK) and E151 whereas C2 interacts with E151 and residues T129 and H9 at the base of the binding cleft (Fig. 7). Therefore, differences in nucleoside specificity for adenosine and inosine must be due to differences in either the lid interactions and/or the E151 site and differences between inosine and guanosine must be due to differences in the amino acids in the binding cleft.

Figure 7.

Nucleoside specificity of TaNK and MjNK. Residues (side chain atoms only) involved in interacting with the nitrogenous base of the nucleoside are rendered as sticks and labeled in the left panel. The nucleosides, also rendered as sticks, are labeled at the top of each column. Boxes indicate activity was observed for the nucleoside substrate.

Figure 8.

Nucleoside specificity of BtNK and MtAK. Residues (side chain atoms only) involved in interacting with the nitrogenous base of the nucleoside are rendered as sticks and labeled in the left panel. The nucleosides, also rendered as sticks, are labeled at the top of each column. Boxes indicate activity was observed for the nucleoside substrate.

BtNK has specificity for inosine and adenosine; however, inosine is not a substrate for MtAK. In comparing the lid domain residues between the two proteins (Fig. 8), there are two differences in the four residues that interact with the C6 amino group of adenosine (or carbonyl group of inosine) and N1 (protonated in inosine): Q173 in MtAK is replaced with a glycine in BtNK and A114 is replaced with threonine. A G170Q mutation in BtNK decreased inosine specific activity, but did not affect adenosine specific activity indicating this residue was important for BtNK broad specificity.6 In comparison, the residues equivalent to Q173 in MtAK are E151 in TaNK, which has specificity for adenosine (though much less compared to inosine) and D164 in MjNK (adenosine activity was detected, but the relative catalytic efficiency was 0.7% that of inosine). Additional differences (beyond E151/D164) in the lid residues must facilitate the binding of both inosine and adenosine. L38* of BtNK and MtAK is replaced with glutamine and asparagine in MjNK and TaNK, respectively; these amino acids are capable of forming a hydrogen bonding network with both N6 and N1 of adenosine and inosine. Consistent with these additional interactions, TaNK has higher catalytic efficiencies and lower KM values for both adenosine and inosine (Table II) than BtNK (KM of 20 μM and kcat/KM of 6,000 M−1s−1 for adenosine and KM of 150 μM and kcat/KM of 80,000 M−1s−1 for inosine). In addition, modeling of cytidine (data not shown) implies the cytidine specificity of TaNK and MjNK is due to N28* and Q33*; this relies on the assumption that the pyrimidine binds in the same site as the purine.

Specificity between inosine and guanosine is distinguished by interactions with E151 and residues in the base of the binding cleft due to differences in the C2 position (amino group in guanosine compared to a hydrogen in inosine). H9, T129, and E151 in TaNK and H13, T138, and D164 in MjNK provide a hydrogen bonding network that can interact with the guanosine C2 amino group. In comparison, BtNK and MtAK do not have guanosine specificity and the equivalent residues are serine, alanine, and glutamine in MtAk and serine, proline and glycine in BtNK. The glutamine (Q173) in MtAK is not sufficient for guanosine binding, implying that H9 and T129 are important in guanosine specificity.

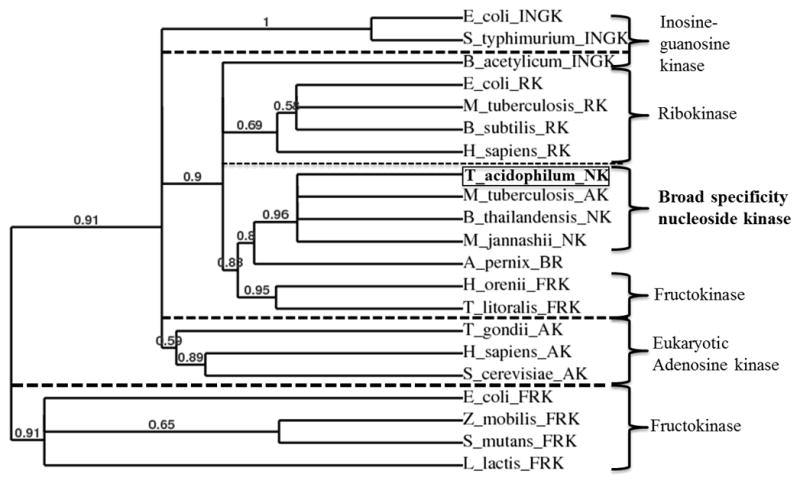

Phylogenetic affiliation

The sequences of 20 annotated and experimentally investigated nucleoside, fructose, and ribose kinases2–4,40,41,43,58–71 from 16 species were compared and a phylogenetic tree was constructed36 (Fig. 8). The two clusters of fructokinases have previously been reported and explained through convergent evolution with one branch evolving from hexokinases and the other evolving from ribokinases.72 The ribo-, adenosine, inosine-guanosine, broad range, and nucleoside kinases all branch separately from hexokinase-derived fructokinases. The eukaryotic adenosine kinases and two of the inosine-guanosine kinases form their own clusters. The ribo-, fructo-, nucleoside, inosine-guanine from B. acetylicum, and the broad range kinase form a branch in which each of the kinases cluster into groups. The broad range kinase (BRK that has both sugar, phosphor-sugar and nucleoside kinase activity) from A. pernix seems more closely related to the nucleoside kinases (though more sequences are needed for analysis). The BRK has distinct differences in the identified residues important in nucleoside specificity, however, that may account for the sugar, phosphor-sugar, and nucleoside broad range specificity (Fig. S1). The separate broad specificity nucleoside kinases cluster indicates they may form a distinct protein family within the ribokinase superfamily. The fact that MtAk clusters with nucleoside kinases indicates that it is distinct from the eukaryotic adenosine kinase.

Conclusion

Structural and sequence comparison of TaNK with BtNK, MjNK, and MtAK indicate that there are a select few residues that control substrate specificity in the nucleoside kinase family of proteins. Residues E151, T129, and H9 determine guanosine specificity and E151 and N28* together increase both adenosine and inosine specificity. Combined, these interactions describe the interactions that determine TaNK’s broad nucleoside specificity. Though phylogenetic analysis relates the NKs to the ribokinase and adenosine kinase families, they cluster separately in a unique subfamily. The findings highlight that, within these large protein families (e.g. PFK-B), more effort is needed to correlate the distinct sequences and structures with experimental functional data in order to facilitate assigning protein function with bioinformatic methods.

Supplementary Material

Figure 9.

Cladogram of nucleoside and sugar kinases. Phylogenetic analysis36 of ribokinases (RK), adenosine kinases (AK), fructokinases (FRK), inosine-guanosine kinases (INGK), broad range kinase (BR) and nucleoside kinases (NK). TaNK is highlighted with a box and the associated broad nucleoside PfkB subfamily in bold font. Information about each sequence can be found in Table S1. Branch support values are given for each branch and only values greater than 50% are considered.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB0845668 and DUE1044858 and COMBREX, funded by NIGMS/NIH Grant RC2-GM-092602. We thank the members of the JCSG high-throughput structural biology pipeline for their contribution to this work. The JCSG is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Protein Structure Initiative U54 grant numbers GM094586 and GM074898, from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (www.nigms.nih.gov). Portions of this research were performed at the APS Beamline 23-ID-D of the GM/CA-CAT and SSRL. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. GM/CA CAT has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (Y1-CO-1020) and the National Institute of General Medical Science (Y1-GM-1104). The SSRL is a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences).

Abbreviations

- AK

adenosine kinase

- ApPFK

Aeropyrum pernix phosphofructokinase

- BthNk

Burkholderia thailandensis nucleoside kinase

- BRK

Broad Range Kinase

- GK

Guanosine Kinase

- INGK

inosine-guanosine kinase

- JCSG

Joint Center for Structural Genomics

- MjNK

Methanocaldococcus jannaschii nucleoside kinase

- NK

nucleoside kinase

- PFK-B

phosphofructokinase B

- RK

ribokinase

- TaNK

Thermoplasma acidophilum nucleoside kinase

References

- 1.Nyhan WL. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons; 2005. Nucloside synthesis via salvage pathways; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen T, Arnfors L, Ladenstein R, Schonheit P. The phosphofructokinase-B (MJ0406) from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii represents a nucleoside kinase with a broad substrate specificity. Extremophiles. 2007;11:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ota H, Sakasegawa S, Yasuda Y, Imamura S, Tamura T. A novel nucleoside kinase from Burkholderia thailandensis: a member of the phosphofructokinase B-type family of enzymes. FEBS J. 2008;275:5865–5872. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen T, Schonheit P. Sequence, expression, and characterization of the first archaeal ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, a non-allosteric enzyme related to the phosphofructokinase-B sugar kinase family, from the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeote Aeropyrum pernix. Arch Microbiol. 2001;177:62–69. doi: 10.1007/s00203-001-0359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnfors L, Hansen T, Schonheit P, Ladenstein R, Meining W. Structure of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii nucleoside kinase: an archaeal member of the ribokinase family. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1085–1097. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906024826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasutake Y, Ota H, Hino E, Sakasegawa S, Tamura T. Structures of Burkholderia thailandensis nucleoside kinase: implications for the catalytic mechanism and nucleoside selectivity. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:945–956. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911038777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Dougherty M, Downs DM, Ealick SE. Crystal structure of an aminoimidazole riboside kinase from Salmonella enterica: implications for the evolution of the ribokinase superfamily. Structure. 2004;12:1809–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klock HE, Koesema EJ, Knuth MW, Lesley SA. Combining the polymerase incomplete primer extension method for cloning and mutagenesis with microscreening to accelerate structural genomics efforts. Proteins. 2008;71:982–994. doi: 10.1002/prot.21786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsliger MA, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Wooley J, Wuthrich K, Wilson IA. The JCSG high-throughput structural biology pipeline. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66:1137–1142. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110038212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:105–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santarsiero BD, Yegian DT, Lee CC, Spraggon G, Gu J, Scheibe D, Uber DC, Cornell EW, Nordmeyer RA, Kolbe WF, Jin J, Jones AL, Jaklevic JM, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. An approach to rapid protein crystallization using nanodroplets. J Appl Crystallogr. 2002;35:278–281. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesley SA, Kuhn P, Godzik A, Deacon AM, Mathews I, Kreusch A, Spraggon G, Klock HE, McMullan D, Shin T, Vincent J, Robb A, Brinen LS, Miller MD, McPhillips TM, Miller MA, Scheibe D, Canaves JM, Guda C, Jaroszewski L, Selby TL, Elsliger MA, Wooley J, Taylor SS, Hodgson KO, Wilson IA, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. Structural genomics of the Thermotoga maritima proteome implemented in a high-throughput structure determination pipeline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11664–11669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142413399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen AE, Ellis PJ, Miller MD, Deacon AM, Phizackerley RP. An automated system to mount cryo-cooled protein crystals on a synchrotron beamline, using compact samle cassettes and a small-scale robot. J Appl Crystallogr. 2002;35:720–726. doi: 10.1107/s0021889802016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stepanov S, Makarov O, Hilgart M, Pothineni SB, Urakhchin A, Devarapalli S, Yoder D, Becker M, Ogata C, Sanishvili R, Venugopalan N, Smith JL, Fischetti RF. JBluIce-EPICS control system for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 67:176–188. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910053916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Bedem H, Wolf G, Xu Q, Deacon AM. Distributed structure determination at the JCSG. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 67:368–375. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910039934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:133–144. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terwilliger TC. Improving macromolecular atomic models at moderate resolution by automated iterative model building, statistical density modification and refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1174–1182. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903009922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winn MD, Murshudov GN, Papiz MZ. Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:300–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Guranovic V, Dutta S, Feng Z, Berman HM, Westbrook JD. Automated and accurate deposition of structures solved by X-ray diffraction to the Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1833–1839. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, 3rd, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins. 2003;50:437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vriend G. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graph. 1990;8:52–56. 29. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terwilliger TC. SOLVE and RESOLVE: automated structure solution and density modification. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:22–37. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm L, Park J. DaliLite workbench for protein structure comparison. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:566–567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heifets A, Lilien RH. LigAlign: flexible ligand-based active site alignment and analysis. J Mol Graph Model. 2010;29:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiefer F, Arnold K, Kunzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D387–392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The UniProt Consortioum. Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D71–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magrane M, Consortium U. UniProt Knowledgebase: a hub of integrated protein data. Database (Oxford) 2011;2011:bar009. doi: 10.1093/database/bar009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie JM, Gascuel O. Phylogeny fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. In: Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. Walker JM, editor. Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews BW. Solvent content of protein crystals. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis IW, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MOLPROBITY: structure validation and all-atom contact analysis for nucleic acids and their complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W615–619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park J, van Koeverden P, Singh B, Gupta RS. Identification and characterization of human ribokinase and comparison of its properties with E. coli ribokinase and human adenosine kinase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3211–3216. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Long MC, Escuyer V, Parker WB. Identification and characterization of a unique adenosine kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6548–6555. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6548-6555.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy MC, Palaninathan SK, Shetty ND, Owen JL, Watson MD, Sacchettini JC. High resolution crystal structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenosine kinase: insights into the mechanism and specificity of this novel prokaryotic enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27334–27342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sigrell JA, Cameron AD, Jones TA, Mowbray SL. Structure of Escherichia coli ribokinase in complex with ribose and dinucleotide determined to 1. 8 A resolution: insights into a new family of kinase structures. Structure. 1998;6:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibbs AC, Abad MC, Zhang X, Tounge BA, Lewandowski FA, Struble GT, Sun W, Sui Z, Kuo LC. Electron density guided fragment-based lead discovery of ketohexokinase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 53:7979–7991. doi: 10.1021/jm100677s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hohnadel DC, Cooper C. The effect of structural alterations on the reactivity of the nucleotide substrate of rabbit muscle pyruvate kinase. FEBS letters. 1973;30:18–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barzu O, Abrudan I, Proinov I, Kiss L, Ty NG, Jebeleanu G, Goia I, Kezdi M, Mantsch HH. Nucleotide specificity of pyruvate kinase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1976;452:406–412. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(76)90190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kayne FJ. Pyruvate Kinase. In: Boyer PD, editor. The Enzymes. Vol. 8. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 353–382. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nowak T, Suelter C. Pyruvate kinase: activation by and catalytic role of the monovalent and divalent cations. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 1981;35:65–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02354821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta RS, Maj MC, Singh B. Pentavalent ions dependency is a conserved property of adenosine kinase from diverse sources: Identification of a novel motif implicated in phosphate and magnesium ion binding and substrate inhibition. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4059–4069. doi: 10.1021/bi0119161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gregory RB, Ainsworth S. The regulatory properties of rabbit muscle pyruvate kinase. The effect of pH. The Biochemical journal. 1981;195:745–751. doi: 10.1042/bj1950745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Jassabi S. Purification and kinetic properties of skeletal muscle lactate dehydrogenase from the lizard Agama stellio stellio. Biochemistry-Moscow. 2002;67:786–789. doi: 10.1023/a:1016300808378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Assa P, Ozkan M, Ozcengiz G. Thermostability and regulation of Clostridium thermocellum L-lactate dehydrogenase expressed in Escherichia coli. Ann Micriobiol. 2005;55:193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Darland G, Brock TD, Samsonoff W, Conti SF. A thermophilic, acidophilic mycoplasma isolated from a coal refuse pile. Science. 1970;170:1416–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3965.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker-Austin C, Dopson M. Life in acid: pH homeostasis in acidophiles. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michels M, Bakker EP. Generation of a large, protonophore-sensitive proton motive force and pH difference in the acidophilic bacteria Thermoplasma acidophilum and Bacillus acidocaldarius. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:231–237. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.231-237.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park J, Gupta RS. Adenosine kinase and ribokinase--the RK family of proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2875–2896. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schumacher MA, Scott DM, Mathews, Ealick SE, Roos DS, Ullman B, Brennan RG. Crystal structures of Toxoplasma gondii adenosine kinase reveal a novel catalytic mechanism and prodrug binding. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:875–893. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu XB, Wu HZ, Ye J, Fan Y, Zhang HZ. Expression, purification, and characterization of recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae adenosine kinase. Acta Biochim Biophy Sin. 2003;35:666–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darling JA, Sullivan WJ, Jr, Carter D, Ullman B, Roos DS. Recombinant expression, purification, and characterization of Toxoplasma gondii adenosine kinase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;103:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawasaki H, Shimaoka M, Usuda Y, Utagawa T. End-product regulation and kinetic mechanism of guanosine-inosine kinase from Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:972–979. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamada Y, Goto H, Ogasawara N. Adenosine kinase from human liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;660:36–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(81)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chua TK, Seetharaman J, Kasprzak JM, Ng C, Patel BK, Love C, Bujnicki JM, Sivaraman J. Crystal structure of a fructokinase homolog from Halothermothrix orenii. J Struct Biol. 2010;171:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sato Y, Yamamoto Y, Kizaki H, Kuramitsu HK. Isolation, characterization and sequence analysis of the scrK gene encoding fructokinase of Streptococcus mutans. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:921–927. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-5-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Q, Liu Y, Huang F, He ZG. Physical and functional interaction between D-ribokinase and topoisomerase I has opposite effects on their respective activity in Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;512:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoffmeyer J, Neuhard J. Metabolism of exogenous purine bases and nucleosides by Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1971;106:14–24. doi: 10.1128/jb.106.1.14-24.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mathews, Erion MD, Ealick SE. Structure of human adenosine kinase at 1. 5 A resolution. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15607–15620. doi: 10.1021/bi9815445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller BG, Raines RT. Identifying latent enzyme activities: substrate ambiguity within modern bacterial sugar kinases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6387–6392. doi: 10.1021/bi049424m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qu Q, Lee SJ, Boos W. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a fructose-6-phosphate-forming and ATP-dependent fructokinase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis. Extremophiles. 2004;8:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s00792-004-0392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson J, Sackett DL, Donkersloot JA. Purification and properties of fructokinase I from Lactococcus lactisLocalization of scrK on the sucrose-nisin transposon Tn5306. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22626–22633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Usuda Y, Kawasaki H, Shimaoka M, Utagawa T. Characterization of guanosine kinase from Brevibacterium acetylicum ATCC 953. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1341:200–206. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zembrzuski B, Chilco P, Liu XL, Liu J, Conway T, Scopes R. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Zymomonas mobilis fructokinase gene and structural comparison of the enzyme with other hexose kinases. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3455–3460. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3455-3460.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. Convergent evolution of similar enzymatic function on different protein folds: the hexokinase, ribokinase, and galactokinase families of sugar kinases. Prot Sci. 1993;2:31–40. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.