Abstract

Dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis pathway is associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia and alcohol abuse. Studies have demonstrated an association between HPA axis dysfunction and gene variants within the cortisol, serotonin and opioid signaling pathways. We characterized polymorphisms in genes linked to these three neurotransmitter pathways and tested their potential interactions with HPA axis activity, as measured by dexamethasone (DEX) suppression response. We determined the percent DEX suppression of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol in 62 unrelated, male rhesus macaques. While DEX suppression of cortisol was robust amongst 87% of the subjects, ACTH suppression levels were broadly distributed from −21% to 66%. Thirty-seven monkeys from the high and low ends of the ACTH suppression distribution (18 ‘high’ and 19 ‘low’ animals) were genotyped at selected polymorphisms in five unlinked genes (rhCRH, rhTPH2, rhMAOA, rhSLC6A4 and rhOPRM). Associations were identified between three variants (rhCRH-2610C>T, rhTPH2 2051A>C and rh5-HTTLPR) and level of DEX suppression of ACTH. In addition, a significant additive effect of the ‘risk’ genotypes from these three loci was detected, with an increasing number of ‘risk’ genotypes associated with a blunted ACTH response (P =0.0009). These findings suggest that assessment of multiple risk alleles in serotonin and cortisol signaling pathway genes may better predict risk for HPA axis dysregulation and associated psychiatric disorders than the evaluation of single gene variants alone.

Keywords: ACTH, CRH, dexamethasone, DST, polymorphism, rhesus, serotonin

The hypothalamic–pituitary−adrenal (HPA) axis is the major neuroendocrine system involved in maintaining physiological homeostasis and general well being. The ‘classic’ HPA response to acute stress is typified by a release of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalmus, which acts on the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH) into circulation, thereby stimulating the adrenal cortex to release the glucocorticoid cortisol. This cascading response is attenuated and homeostasis is defended through a negative feedback pathway, where cortisol binds to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in the hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal cortex, and to mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) in the hippocampus (de Kloet et al. 2005; Jacobson & Sapolsky 1991; Pace & Spencer 2005). Dysregulation of the HPA axis pathway has been linked to a range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including anxiety, MDD, PTSD, schizophrenia and alcohol abuse (Carroll et al. 1976; de Kloet et al. 2005; Goeders 2003; Goodyer et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2008; Yehuda 1997). Thus, the HPA axis pathway has emerged as a focal point for investigating potential mechanisms and risk factors underlying a variety of behavioral disorders.

Dexamethasone (DEX) is a potent synthetic glucocorticoid that binds with high affinity to glucocorticoid and MRs. The DEX suppression test (DST) is commonly used for evaluating the sensitivity of the HPA axis negative feedback pathway. Circulating levels of cortisol or ACTH are compared before and 10–20 h after administration of a low dose of DEX (Kalin et al. 1981; Schuld et al. 2006). The DST has also been widely used to test specifically the association between negative feedback sensitivity and psychiatric disorders. A blunted DST response has been linked to MDD (Lopez-Duran et al. 2009; Wingenfeld et al. 2010), while an enhanced DST response has been associated with PTSD (de Kloet et al. 2006; Grossman et al. 2003; Strohle et al. 2008; Yehuda et al. 2004) and anxiety (Hori et al. 2010).

Numerous studies have been devoted to identifying variables that contribute to different aspects of HPA axis dysfunction, with the results implicating a wide range of genes and signaling pathways. As anticipated, variants in genes directly involved in cortisol regulation, including the corticotrophin-releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1) gene, have reported associations (Heim et al. 2009; Tyrka et al. 2009). Other polymorphisms in serotonergic genes have also been implicated, including the promoter length polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), (Chen et al. 2009; Lesch et al. 1996; O’Hara et al. 2007; Wust et al. 2009) and in the monoamine oxidase A gene (MAOA-LPR) (Brummett et al. 2008; Jabbi et al. 2007). The rhesus macaque tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene (rhTPH2), includes a A2051C variant that has been associated with morning cortisol levels (Chen et al. 2006). The mu-opioid receptor variant, OPRM1 A118G has been associated with blunted cortisol response to stress (Hernandez-Avila et al. 2007; Pratt & Davidson 2009; Wand et al. 2002).

The rhesus macaque has emerged as an excellent model for HPA axis dysregulation studies, owing to the similar neuroanatomical, behavioral and genetic features shared with humans (Geyer et al. 2000; Gibbs et al. 2007; Kalin et al. 2007; Schwandt et al. 2010). The rhesus macaque genome also includes common polymorphisms that are orthologous to human gene variants implicated in HPA axis regulation, including rh5-HTTLPR (Bennett et al. 2002), rhMAOA-LPR (Newman et al. 2005; Wendland et al. 2006), and rhOPRM1 C77G, which is functionally similar to the human OPRM1 A118G variant (Miller et al. 2004). Other rhesus gene variants, such as those in the corticotrophin-releasing hormone gene (rhCRH) (Barr et al. 2008) and the rhTPH2 gene (Chen & Miller 2008, Chen et al. 2006; 2010b) provide further opportunity to investigate their potential contributions to variability in HPA axis reactivity. Finally, when captive bred rhesus macaques are raised in highly managed settings, the environmental contributions to HPA axis dysregulation are minimized, affording increased power to detect genetic effects, as compared with similar human studies.

Although previous human and rhesus macaque studies have implicated several genes and pathways in HPA axis regulation, many of the associations were established using different endocrine measures or test conditions. The varying study designs and measures have made it difficult to directly compare the relative genetic effects across studies. We approached this limitation by studying a cohort of healthy male rhesus macaques with a known, similar life history, by analyzing in parallel polymorphisms located in five unlinked genes (rhCRH, rhSLC6A4, rhMAOA, rhTPH2 and rhOPRM1) and by utilizing a consistent HPA axis measure, DEX suppression of ACTH. Using this approach, we identified three genotypes associated with level of DEX suppression of ACTH. This enabled us to explore potential additive effects among the three associated variants and the level of ACTH suppression.

Materials and methods

Animals

Indian rhesus macaque males, ranging from 4 to 8 years old, were screened for inclusion in this study. All candidate subjects were genetically tested to confirm the identity of their parents, and pedigree analysis was used to select 62 final subjects that were separated by at least three generations. All of the subjects were raised by their mothers in a social group setting until at least 3 years of age. Animals were individually housed in 76 × 60 × 70 cm stainless steel cages for a minimum of 2 months prior to the onset of this study. Care was taken to minimize pain or discomfort of all of the animals in this study. All protocols were carried out in accordance with the Oregon Health Sciences University Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and in compliance with the guidelines for the care and use of animal resources (Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996).

Dexamethasone suppression test

The dexamethasone suppression test (DST) was used to assess the responsiveness of the hypothalamus and pituitary to negative feedback inhibition by DEX in all 62 animals. Since DEX binds with high affinity to the GR, it was used in relatively small amounts to test sensitivity to negative feedback (Kalin & Shelton 1984; Kalin et al. 1981). After a morning (0800 h) blood sample was taken for a baseline measures, a low dose (130 µg/kg, i.m.) of DEX was given that evening (2200 h). The next morning at 0800 h, another blood sample was taken and assayed for ACTH and cortisol using identical procedures as for the baseline measurements. For each blood collection, animals were sedated by administration of 8 mg/kg ketamine (i.m.) and a femoral blood sample was obtained with a 22 g × 1 in. vacutainer needle and a 3-ml vacutainer hematology tube (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). All blood samples were stored on ice until centrifuged (approximately 5 min). Samples were spun at 3000 r.p.m. for 15 min at 4°C in a Beckman Coulter refrigerated centrifuge (Model Allegra 21R, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). The plasma was pipetted into 2 ml microtubes in 100 µl aliquots. The remaining blood fractions were stored for DNA extraction and genotype analysis. Plasma samples were frozen at −80°C and stored until being sent to Yerkes Endocrine Core Laboratory (http://www.yerkes.emory.edu/DIV/RSRCHRES/assay/) for radioimmunoassay analysis of cortisol and ACTH levels. The percent suppression was calculated as [(Pre-DEX−Post-DEX)/Pre-DEX] × 100.

Genotype analysis

Thirty-seven of the 62 animals were genotyped for polymorphisms in five unlinked genes involved in HPA axis activity (rhCRH, rhTPH2, rhMAOA, rhSLC6A4 and rhOPRM). Animals were chosen for genotyping based on their percent DEX suppression of ACTH, and included the lowest and highest 30% of the distribution (18 animals with ‘high’ and 19 animals with ‘low’ DEX suppression of ACTH). Genomic DNA was extracted from each stored blood sample using the MagnaSil Genomic extraction kit (Promega, Inc., Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturers protocol. Seven variants across these five genes were chosen based on previous publication in related studies. The rhTPH2 2051A>C variant falls within the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the gene, and has been predicted to alter mRNA folding (Chen et al. 2006). The rhCRH-2232C>G promoter variant had previously been associated with plasma ACTH levels in rhesus macaques (Barr et al. 2008), while rhCRH-2610C>T, an unlinked and more common polymorphism in the 5′-flanking region, was of interest because it flanks a potential glucocorticoid response element (GRE) binding site (Malkoski & Dorin 1999), and might affect the CRH expression response to DEX. The rhOPRM1 77C>G variant has been associated with both basal cortisol levels (Miller et al. 2004) and cortisol response to acute stress (Schwandt et al. 2011). The rh5-HTTLPR length polymorphism has predominant alleles referred to as small (S) and large (L) which differ by 21 base pairs, though a rare extra-large (XL) allele has also been reported (Barr et al. 2004b; Rogers et al. 2006). The rh5-HTTLPR S allele had been previously reported to be associated with increased levels of ACTH in response to acute stress among male rhesus macaques (Barr et al. 2004a). The rhTPH2-1485(AT)n polymorphism is located in the 5′-flanking region and has been reported to influence plasma ACTH levels (Chen et al. 2010b). The X-linked rhMAOA contains a variable length promoter polymorphism in the 5′-region, with 5, 6 and 7 copies of an 18-bp repeat previously reported in rhesus macaques. The rhMAOA-LPR 7 copy allele was reported to have lower transcriptional activity than the 5 and 6 copy alleles, based upon in vitro reporter assays (Newman et al. 2005).

SNP genotyping

The SNP genotyping was carried out by PCR amplification of each target region, followed by direct Sanger sequencing. The primers used in this study were also used in previously published studies, as indicated: rhTPH2 2051A>C 5′-TTGAAATTCTGAAAGACACCAGA-3′ and 5′-ACTGCTTCAGGCAAATCACA-3′ (Chen et al. 2006); rhCRH -2610C>T and -2232C>G, 5′-GGTTCTCATTTAAACCGAGTGATC-3′ and 5′-AAGTGGCTCCAACTAGGGAGTAAG-3′ (Barr et al. 2008); rhOP RM1 77C>G 5′-TCCCTGCCAGATTTTAAGGA-3′ and 5′-GATGGAGTAGAGGGCCATGA-3′ (Miller et al. 2004). The PCR reactions included 25 ng genomic DNA, 1 × Taq polymerase buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dNTPs, 1 pM of each primer, 0.12 u Taq DNA Polymerase (Fermentas, Inc., Glen Burnie, MD, USA). The amplification conditions were 95°C for 2 min, then thirty-five cycles of: 30 seconds at 92°C, 30 seconds at 56–62°C and 1min at 72°C, with a final extension stage of 72°C for 10 min. Each PCR reaction was incubated with 0.25 units of exonuclease 1 and 0.31 units Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) at 37°C for 30 min, and then inactivated by incubation at 95°C for 5 min. PCR products were sequenced in both directions on an ABI3730 XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA), using fresh aliquots of the same primers as used for PCR amplification. DNA sequences were analyzed using Sequencher 4.8 software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Variable number tandem repeats

Three Variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) were sequenced across three genes: rh5-HTTLPR polymorphism of rhSLC6A4, rhMAOA-LPR polymorphism, and the -1485(AT)n polymorphism of rhTPH2. The rh5-HTTLPR region was amplified using primers 5′-FAM-TCGACTGGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC-3′ and 5′-gtttcttCAGGGGAGATCCTGGGAGGGA-3′, yielding 398, 419 and 440 bp products for the S, L and XL alleles, respectively. The PCR reactions included 25 ng genomic DNA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dNTPs, 1 pM of each primer, 1 × reaction buffer, and 0.12 units Taq DNA polymerase. The PCR conditions were 92°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 92°C for 30 seconds, 66°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension stage of 72°C for 10 min. rhMAOA-LPR was amplified using primers 5′-PET-GAGCACAAACGCCTCAGCC-3′ and 5′-gtttcttGGACCTGGGAAGTTGTGC-3′, generating 188, 206, 224 and 242 bp products for the 4, 5, 6 and 7 copy number alleles, respectively. The PCR reaction mixture and amplification protocol were the same as for rh5-HTTLPR, except for the use of 62°C as the annealing temperature. RhTPH2-1485(AT)n region was amplified using F primer 5′-cacgacgttgtaaaacgacTTTTCCCTCGCTTTCACATC-3′, R primer 5′-gtttcttAAAATTCACAAGGCCACAGG-3′, and a FAM-labeled M13F primer: 5′-cacgacgttgtaaaacgac-3′, producing a 453, 455 and 457 bp product for the 6, 7 and 8 repeat alleles, respectively. The PCR reaction included 30 ng genomic DNA, 4.4 pM M13 primer, 1.2 pM of forward primer, 4.4 pM reverse primer and 9 ul True Allele PCR Premix (Applied Biosystems Inc.) in a final volume of 15 ul. The reaction was incubated at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 57.5°C for 45 seconds and 72°C for 45 seconds, followed by eight cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 53°C for 45 seconds and 72°C for 45 seconds, with a final extension stage of 72°C for 10 min.

The PCR products for the VNTR assays were applied to an ABI3730 XL DNA Analyzer for separation and detection, incorporating a 600LIZ size standard with the PCR products at a 1:1 ratio (Applied Biosystems Inc.). The output files were visualized and product sizes were determined (Fig. S1) using Gene Mapper 4.0 software (Applied Biosystems Inc.). The sequence content of the amplification products were confirmed by PCR amplifying DNA from individuals with homozygous genotypes with unlabeled primers, and by direct DNA sequencing of PCR products. The rhTPH2-1485(AT)n PCR products were also sequenced directly to insure that the (AT)6 variant was not overlooked in this study.

Statistical analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients were estimated to determine associations between baseline levels of cortisol and ACTH and % suppression in response to DEX, including pair-wise comparisons of baseline ACTH and % ACTH suppression as well as % ACTH suppression and % cortisol suppression.

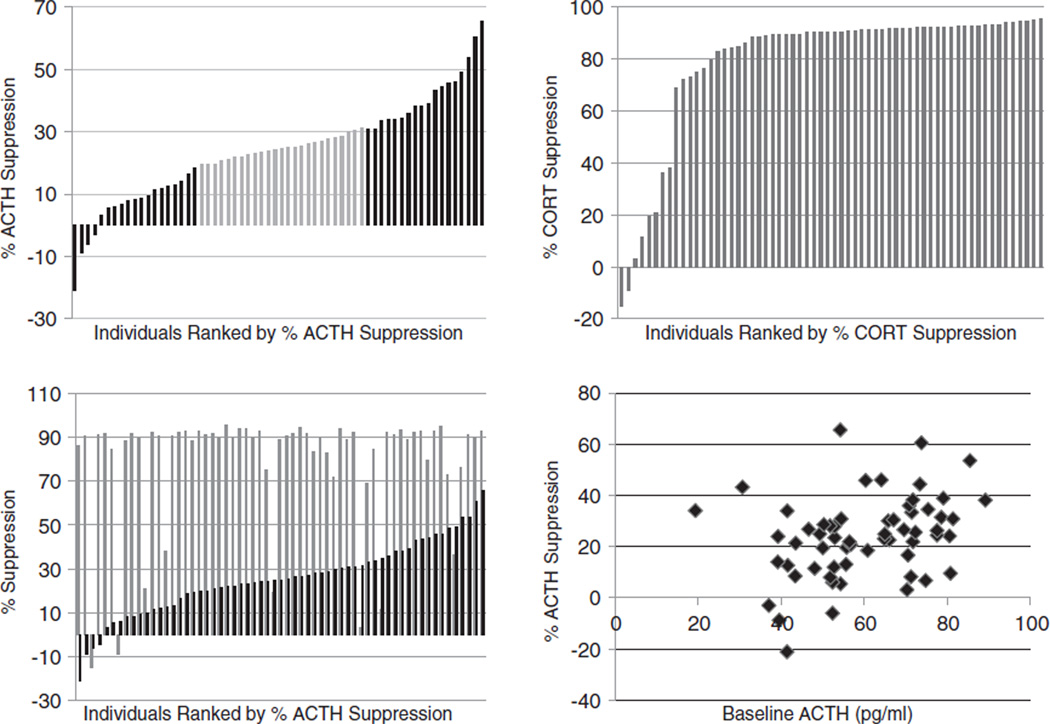

Thirty-seven animals were selected for genotyping at seven polymorphic loci based on their percent DEX suppression of ACTH: 19 animals with ‘low’ ACTH suppression levels (−6% to 18%) and 18 animals with ‘high’ suppression (31–66%; Fig. 1a). We did not include equal number of subjects in both genotype groups, because it would have required selecting just one of two possible animals with equivalent ACTH suppression levels. χ2 analysis was used to determine whether SNP genotypes deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Analyses of statistical associations between the level of ACTH suppression (low vs. high) and genotypes at these loci were performed using the Cochran–Armitage trend test, a standard test of single-SNP association which is robust to potential violations of HWE. To test associations at each locus individually, genotypes were coded to indicate the number of copies of a ‘risk’ allele, where the ‘risk’ allele for rhCRH-2232C>G was the G allele, rhCRH-2610C>T was the T allele, rhOPRM1 77C>G was the G allele, rhTPH2 2051A>C was the C allele, rh5-HTTLPR was the S allele. For rhMAOA-LPR and rhTPH2-1485(AT)n, increasing promoter length and copies of the dinucleotide were assessed for risk. All polymorphisms were analyzed in separate models to determine whether increasing copies of the ‘risk’ allele at each locus were associated with blunted HPA axis response (‘low’ suppression).

Figure 1. Distribution of dexamethasonse suppression measures among 62 unrelated rhesus macaques.

(a) Animals are ranked by percent dexamethasone (DEX) suppression of adrenocorticotropic hormome (ACTH). Thirty-seven individuals from either end of the distribution that were included in the genotype analysis are indicated by black bars. (b) Animals are ranked by percent DEX suppression of cortisol. (c) The percent cortisol suppression level (gray) and percent ACTH suppression level (black) are shown side by side for each animal. (d) Plot of morning baseline ACTH levels (pre-DEX administration) and the percent ACTH suppression following DEX administration for each individual.

An additional model was then run to determine whether the total number of ‘risk’ genotypes across the loci significantly associated with HPA axis response had an additive effect. The number of ‘risk’ genotypes was coded such that a value of ‘0’ indicated the animal had no ‘risk’ genotype at any locus significantly associated with HPA axis response, a value of ‘1’ indicated that the animal had a ‘risk’ genotype at only one of the loci significantly associated with HPA axis response and so on.

Finally, Fisher exact tests were also performed to ensure that results of all models were robust to risk model (i.e. dominant, recessive or additive). Effect sizes were determined using Cramer’s V analysis. A Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple testing across the seven loci given these loci are unlinked and the genotypes are uncorrelated. Thus, a value of P =0.0071 was used to indicate statistical significance at the α < 0.05 level for these analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using the PROC FREQ procedure in the SAS System for Windows, Release 9.2.

Results

Dexamethasone suppression survey

A population survey of HPA axis negative feedback responsiveness was conducted in 62 unrelated, healthy, male rhesus macaques using a low dose DST. The study showed a broad distribution of ACTH suppression values, ranging from a low of −21% to a high of 66% suppression (Fig. 1a). Four individuals had negative suppression levels, indicating an increase in circulating ACTH following DEX administration. In contrast, the cortisol suppression values for the same individuals were more uniform, with 90% of the animals having a cortisol suppression value of 70% or more, suggesting that this dose of DEX resulted in a ‘ceiling’ effect on cortisol (Fig. 1b). The percent ACTH suppression was not significantly correlated with cortisol suppression (R =0.1835, P =0.1570); only four of the eight animals with low cortisol suppression (−15% to 38%) also had low ACTH suppression (−6% to 18%; Fig. 1c). The broad distribution of ACTH suppression levels among the rhesus macaques suggested that this measure would be well suited to genetic investigation. Moreover, the baseline ACTH values were moderately correlated, (R=0.3630, P =0.0040; Fig. 1d), suggesting that ACTH suppression levels may also be influenced by individual variation in HPA axis negative feedback regulation.

Genotype analysis

Genotype frequencies for the seven polymorphic loci analyzed in 37 animals are shown in Table 1 stratified by ‘low’ and ‘high’ suppression of DEX suppression of ACTH. For the rhOPRM1 77C>G and rhCRH-2232C>G polymorphisms, none of the animals were homogygous for the ‘risk’ allele (i.e. GG). Thus, the association test was limited to the CC and CG genotype groups for these polymorphisms. Owing to low genotype frequencies, some of the genotype groups were collapsed to enable association analyses. Specifically, the rh5-HTTLPR S/S and L/XL genotypes were both rare, so the L/L and L/XL genotypes were combined and the S/S and S/L genotypes were combined. Also owing to the low frequency of the rhCRH-2610C>T CC genotype, the CC and CT genotypes were combined. Two of the SNPs deviated from HWE: rhTPH-1485(AT)n (χ2df=1, P =0.0367) and rh5-HTTLPR (χ2df=3, P =0.0441).

Table 1.

Genetic association test results using a Cochran–Armitage Test of Trend. Genotypes at seven loci were tested for their association with ‘high’ and ‘low’ levels of DEX suppression of ACTH among 37 rhesus macaques

| High | Low | Total | Cochran–Armitage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | Genotype | n = 18 | n = 19 | n = 37 | Test of Trend |

| rhTPH-1485(AT)n* | 7,7 | 9 | 8 | 17 | Z = 0.11 |

| 7,8 | 3 | 8 | 11 | P = 0.9164 | |

| 8,8 | 5 | 3 | 8 | ||

| rhTPH 2051A>C | AA | 7 | 1 | 8 | Z = −2.50 |

| AC | 6 | 7 | 13 | P = 0.0125 | |

| CC | 5 | 11 | 16 | ||

| rh5-HTTLPR† | S/S | 1 | 0 | 1 | Z = −1.9940 |

| S/L | 2 | 9 | 11 | P = 0.0462 | |

| L/L | 13 | 10 | 23 | ||

| L/XL | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| rhOPRM1 77C>G‡ | CC | 13 | 13 | 26 | Z = −0.2528 |

| CG | 5 | 6 | 11 | P = 0.8004 | |

| GG | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| rhCRH-2232C>G§ | CC | 17 | 17 | 34 | Z = −0.5537 |

| CG | 1 | 2 | 3 | P = 0.5798 | |

| GG | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| rhCRH-2610C>T¶ | CC | 3 | 1 | 4 | Z = −2.4617 |

| CT | 9 | 4 | 13 | P = 0.0138 | |

| TT | 6 | 14 | 20 | ||

| rhMAOA-LPR | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Z = −0.1436 |

| 5 | 7 | 3 | 10 | P = 0.8859 | |

| 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||

| 7 | 9 | 10 | 19 | ||

| # Risk genotypes | 0 | 7 | 1 | 8 | Z = −3.3215 |

| 1 | 8 | 6 | 14 | P = 0.0009∥ | |

| 2 | 3 | 8 | 11 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

rhTPH-1485(AT)n genotype data missing for one animal in the ‘high’ category.

rh5-HTTLPR genotype groups were collapsed genetic association test with S/S and S/L genotypes in one group and L/L and L/XL genotypes in second group.

rhOPRM1 77C>G genetic association test was limited to the CC and CG genotypes.

rhCRH-2232C>G genetic association test was limited to the CC and CG genotypes.

rhCRH-2610C>T genotypes CC and CT were collapsed for genetic association test.

Analysis remains statistically significant at α < 0.05 level after adjustment for multiple testing.

Results of the Cochran–Armitage trend tests indicated that genotypes at three polymorphic loci were significantly associated with level of DEX suppression of ACTH: rhTPH2 2051A>C, rh5-HTTLPR and rhCRH-2610C>T (Table 1). Specifically, increasing copies of the ‘risk’ alleles at these loci (i.e. the C allele at rhTPH2 2051, the S allele at rh5-HTTLPR and the T allele at rhCRH-2610) were associated with a blunted or ‘low’ ACTH suppression response to DEX. These associations reflected low to medium effect sizes with Cramer’s V values of 0.4289, 0.3278 and 0.4047, respectively. No other alleles were associated with ACTH suppression. The conclusions of the Fisher Exact Tests were consistent with these results, indicating that the rhTPH2 2051A>C, rh5-HTTLPR and rhCRH-2610C>T polymorphisms were associated with ACTH suppression (P =0.0283, P = 0.0798, P = 0.0217, respectively). However, after adjustment for multiple testing, none of these results remained statistically significant.

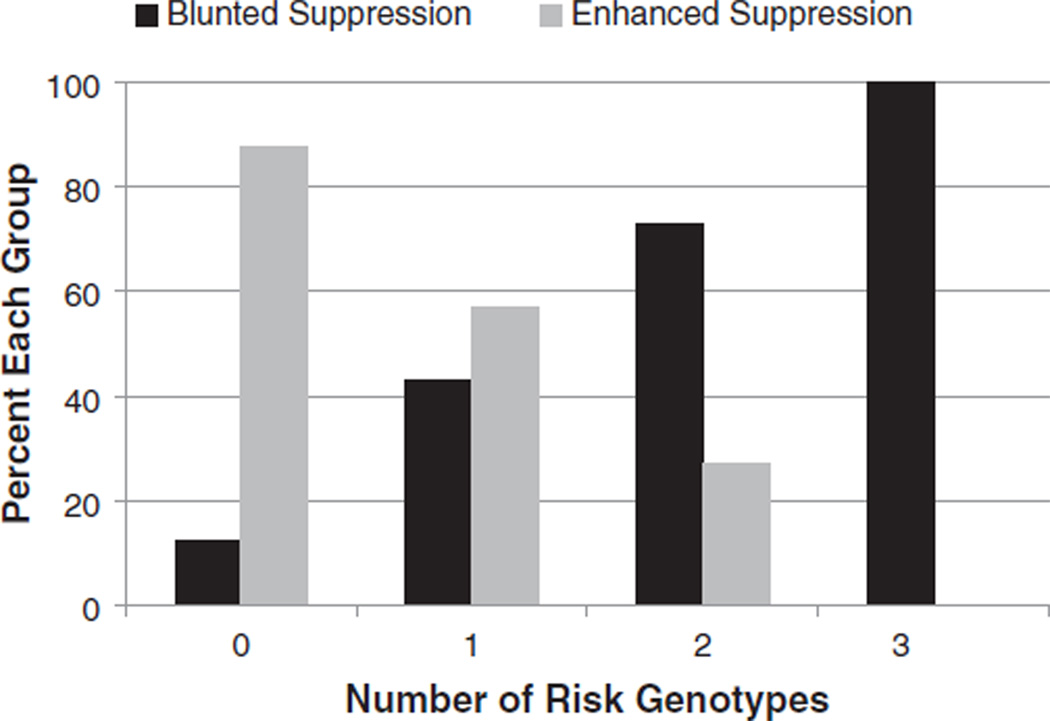

In a secondary analyses, we analyzed whether the three ‘risk genotypes’ associated with blunted ACTH suppression (i.e. the CC genotype at rhTPH2 2051, the S/S or S/L genotype at rh5-HTTLPR, and the TT genotype at rhCRH-2610) had an additive effect. Variants for which no significant association was detected were not included in this analysis, since a risk genotype was not clearly identified. Results of this analysis indicated that the increasing number of risk genotypes is associated with blunted ACTH suppression (P = 0.0009; Table 1, Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Relationship between dexamethasone (DEX) suppression of ACTH and genetic load at rhCRH-2610T>C, rhTPH2 2051A>C, and rhSLC6A4 5-HTTLPR.

Individuals were grouped according to their number of risk genotypes (rhCRH-2610TT, rhTPH2 2051CC, rh5-HTTLPR SS or SL). The percent of individuals having 0, 1, 2 or all three risk genotypes within the enhanced suppression group (gray) or blunted suppression group (black).

Also of note, though the rhMAOA-LPR has been reported to include 5, 6 and 7 copies of an 18-bp repeat in rhesus macaques, we identified a four-copy allele in two individuals. The four repeat variant was initially detected by separating the fluorescently labeled rhMAOA-LPR PCR amplification products on a DNA Analyzer 3730XL (Applied Biosystems Inc.), which provides high resolution and accurate fragment size estimation (Fig. S1). All of the alleles (4–7) were also sequenced and confirmed to differ by a single 18 bp repeat, as predicted. The rhMAOA-LPR allele sequences were deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) for public access (JN207465-JN207468).

Discussion

This study identified an association between level of DEX suppression of ACTH and variants in three independent genes: a 5′-polymorphism in the rhCRH gene (-2610C>T), a 3′-UTR variant in rhTPH2 (2051A>C) and the 5′-length polymorphism in the rhSLC6A4 gene (5-HTTLPR). In addition, we detected a significant additive effect of the genotypes, indicating that as the number of risk genotypes increases, the DEX suppression of ACTH becomes more blunted. This finding suggests an additive effect of three CRH and serotonin-related gene polymorphisms that is more significant than the contribution of any of the individual genotypes alone to the DEX suppression of ACTH. It follows, therefore, that the parallel genotype analysis of multiple gene variants could be critical for effectively evaluating HPA dysfunction risk. It will also be valuable to determine whether additive genetic effects contribute to other clinically relevant endocrine measures, such as morning cortisol levels or DST suppression of cortisol.

It will also be important to establish whether increased genetic load in these same genes correlates with DEX suppression of ACTH in humans. Blunted DEX response has been linked to MDD (Lopez-Duran et al. 2009; Wingenfeld et al. 2010), and the opposite trait, enhanced DEX responsiveness, has been associated with PTSD (de Kloet et al. 2006; Grossman et al. 2003; Strohle et al. 2008; Yehuda et al. 2004). Thus, these findings have particular relevance to efforts aimed at identifying individuals with increased risk for developing PTSD or major depression. Our study suggests that it would be useful to investigate whether genetic load across the same genes in the CRH and serotonin signaling pathways is also associated with DST sensitivity and the associated disorders in human populations.

The full network of genes that contribute to HPA axis regulation is likely to be very complex. Indeed, genetic interactions between MAOA and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphisms have been linked to ACTH response to stress (Jabbi et al. 2007). Others have showed an interaction between 5-HTTLPR variants and a dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) allele that was associated with cortisol response to social stress (Armbruster et al. 2009). Taken together, these studies suggest that variants within the cortisol, serotonin and catecholamine (dopamine, epinephrine and norepinephrine) signaling pathways will be important to evaluate in parallel to effectively understand genetic risk for HPA axis dysregulation and the wide range of associated neuropsychiatric diseases.

Considering details of this study design, it is notable that the dose of DEX that was administered was too low to cross the rhesus macaque blood–brain barrier (Cole et al. 2000), and thus the suppression of ACTH likely reflects HPA axis regulatory activity mediated through the negative feedback at the level of the pituitary and adrenal glands. Ultimately, the suppression of cortisol will interact with central mechanisms to restore normative values. It appears that the pituitary and ACTH response can recover faster than the adrenal and cortisol response to DEX. Specifically, broad distributions of ACTH suppression levels were measured at 10 h post-DEX treatment, whereas the cortisol suppression levels were more extensive and uniform. Thus, the findings in this study may primarily reflect genes involved in hypothalamic–pituitary mechanisms involved in HPA axis feedback regulation when the adrenal is hyporesponsive, as with the alcoholism (Adinoff et al. 2005).

The rate of DEX metabolism across animals is an unknown variable in these studies, and could contribute to the variation in ACTH suppression values. However, given the highly consistent level of cortisol suppression and the findings of significant association with rhCRH and serotonin-related genes, the contribution of metabolic variation does not appear to have masked the regulatory mechanisms involved in DEX suppression.

This study required administration of a low dose of ketamine prior to each blood draw. Although ketamine has been reported to alter HPA axis activity (Broadbear et al. 2004), we previously compared the ACTH levels measured in macaques on different days, both with or without ketamine administration and did not identify a change in either baseline or DEX suppression values (data not shown).

One limitation of this study is that we only genotyped 37 of the 62 animals: animals in the lowest 30% of the distribution of percent DEX suppression of ACTH (n = 19) and animals in the highest 30% of the distribution (n = 18). Although this ‘extremes’ study design increased our power to detect genotypes significantly associated with ‘low’ and ‘high’ ACTH suppression, it limited our ability to analyze ACTH suppression as a quantitative outcome. Future studies will aim to genotype additional animals and allow the analyses of these loci as quantitative trait loci (QTLs) of HPA axis function.

This study identified a contribution of the rhCRH-2610T>C variant to the relative DEX suppression of ACTH. Although the identified variant falls within the 5′-region of the gene, it is not known whether it functionally alters rhCRH expression, or alternatively, is in linkage disequilibrium with functional variants located beyond the boundaries of our analysis. The finding of a contribution of rhCRH variant to DEX suppression of ACTH supports the involvement of CRH interacting with feedback regulation through the adrenal glands and pituitary.

The rhTPH2 2051A>C polymorphism was previously associated with both morning plasma cortisol level and DEX suppression of cortisol (Chen et al. 2006), and this study provides additional support for the role of this gene in HPA axis regulation. Specifically, we found that CC homozygous individuals tended to exhibit a more blunted ACTH response following DEX administration. Because the rhTPH2 2051 C allele has been linked to lower reporter gene expression levels (Chen et al. 2006), the dampened DEX suppression of ACTH may reflect decreased levels of rhTPH2 mRNA and, by extension, decreased levels of serotonin. However, this working model will require future study to confirm.

The 5-HTTLPR variant is a well-studied polymorphism in both humans and rhesus macaques. In this study, rhesus macaques that carried the S allele were significantly associated with attenuated DEX suppression of ACTH. It was previously reported that male rhesus macaques with an S allele had increased levels of ACTH in response to acute stress, whereas in females, elevated ACTH was dependent on both the S allele and a history of early life adversity (Barr et al. 2004a). This sex effect may explain why an altered endocrine response was detected in this study of male macaques, while investigations including a combination of male and female animals reported a dependence on both the S allele and early life stress to detect altered cortisol (Capitanio et al. 2005), ACTH (Barr et al. 2004b) or temperament (Champoux et al. 2002). The mechanism by which the rhesus 5-HTTLPR S allele affects serotonin signaling continues to be debated. The S allele has been linked to lower expression levels of the serotonin transporter gene rhSLC6A4 (Bennett et al. 2002), reduced serotonin uptake rates in lymphocytes (Singh et al. 2010) and altered cortical development in adults (Jedema et al. 2010).

The rhOPRM1 77C>G variant, as with the human 118A>G variant, results in an amino acid substitution that increases the binding affinity of β-endorphin by the receptor (Miller et al. 2004). In a previous study, the 77C>G variant was associated with cortisol levels in macaques experiencing stress (Singh et al. 2010). To our knowledge, this is the first study to report an investigation of either the 77C>G or the 118A>G variant with DEX suppression of ACTH, and we did not detect a significant association. However, since no GG homozygotes were present in this study, the statistical comparison was between CG and CC individuals, which may have reduced our power to detect significant differences across genotypes.

Our ability to detect an association between DEX suppression of ACTH and genetic load was likely improved by the use of a study design that leveraged the relatively limited amount of environmental variance in this monkey population. The broad distribution of ACTH suppression levels were detected among a cohort of healthy, unrelated, male monkeys of similar age, members of a large captive breeding colony that experience similar group housing, diet and maternal access. The relatively homogenous rhesus macaque population thus provided a consistent baseline, with minimal environmental variance, presumably increasing the proportion of the genetic contributions to the measured trait. Similar studies of human populations are challenged by the presence of unknown environmental variables, which may contribute to HPA axis dysregulation through independent, epigenetic mechanisms. In this regard, the rhesus macaque provides a powerful and relevant model to investigate the genetic contributions to HPA axis dysregulation.

It will be interesting to explore whether environmental factors, such as adverse life history, might mirror the effect of increased genetic load in certain genes and pathways. It is clear that early life stress (ELS), such as childhood adversity, also contributes to HPA axis dysregulation (McCrory et al. 2010; Owen et al. 2005; Sanchez 2006). Moreover, previous reports of interactions between stress and individual genotypes on HPA axis activity (Barr et al. 2004b; Bet et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2010a; Gillespie et al. 2009; McCormack et al. 2009; Tyrka et al. 2009; Witt et al. 2011) support the hypothesis of inherent genetic risk being elevated by a history of adversity. Findings of a link between promoter methylation of the GR gene (NR3C1) and altered cortisol response supports the role of epigenetics in translating ELS into increased risk for HPA axis dysregulation (McGowan et al. 2009; Oberlander et al. 2008). Such epigenetic changes could provide an alternate mechanism for effectively increasing genetic load in key HPA axis regulatory genes and pathways. Future studies are needed to test this possibility.

In summary, this study presents evidence for the contribution of serotonin and cortisol signaling pathway gene variants to HPA axis regulation in non-human primates. Moreover, a novel finding of significant additive effects of 5-HTTLPR and variants in the rhTPH2, rhCRH genes to the DEX suppression of ATCH was identified. Replicated findings of the additive genetic effects in human studies would suggest that the coordinated evaluation of multiple key genes may more accurately predict individual risk for HPA axis dysregulation and associated neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Variable length alleles at the rh5-HTTLPR and rhMAOA-LPR loci. (a) Two individuals with short/long (S/L) and long/extra long (L/XL) rh5-HTTLPR genotypes are shown. (b) Four individuals with 4, 5, 6 and 7 copy alleles at rhMAOA-LPR are shown.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Dr. Kevin Nusser and the Division of Animal Resources at the Oregon National Primate Research Center in orchestrating the DST population survey. We also thank Drs Byung Park and Beth Wilmot, of the ONPRC Biostatistics Unit, for their contributions to the statistical analysis. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AA013510, AA020928 and OD011092.

Footnotes

The authors reported no biomedical financial interests or other potential conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

References

- Adinoff B, Krebaum SR, Chandler PA, Ye W, Brown MB, Williams MJ. Dissection of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis pathology in 1-monthabstinent alcohol-dependent men part 1: adrenocortical and pituitary glucocorticoid responsiveness. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:517–527. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000158940.05529.0A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster D, Mueller A, Moser DA, Lesch KP, Brocke B, Kirschbaum C. Interaction effect of D4 dopamine receptor gene and serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism on the cortisol stress response. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:1288–1295. doi: 10.1037/a0017615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CS, Newman TK, Schwandt M, Shannon C, Dvoskin RL, Lindell SG, Taubman J, Thompson B, Champoux M, Lesch KP, Goldman D, Suomi SJ, Higley JD. Sexual dichotomy of an interaction between early adversity and the serotonin transporter gene promoter variant in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004a;101:12358–12363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403763101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CS, Newman TK, Shannon C, Parker C, Dvoskin RL, Becker ML, Schwandt M, Champoux M, Lesch KP, Goldman D, Suomi SJ, Higley JD. Rearing condition and rh5-HTTLPR interact to influence limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress in infant macaques. Biol Psychiatry. 2004b;55:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CS, Dvoskin RL, Yuan Q, Lipsky RH, Gupte M, Hu X, Zhou Z, Schwandt ML, Lindell SG, McKee M, Becker ML, Kling MA, Gold PW, Higley D, Heilig M, Suomi SJ, Goldman D. CRH haplotype as a factor influencing cerebrospinal fluid levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, temperament, and alcohol consumption in rhesus macaques. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:934–944. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.8.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AJ, Lesch KP, Heils A, Long JC, Lorenz JG, Shoaf SE, Champoux M, Suomi SJ, Linnoila MV, Higley JD. Early experience and serotonin transporter gene variation interact to influence primate CNS function. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:118–122. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bet PM, Penninx BW, Bochdanovits Z, Uitterlinden AG, Beekman AT, van Schoor NM, Deeg DJ, Hoogendijk WJ. Glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms and childhood adversity are associated with depression: new evidence for a gene-environment interaction. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:660–669. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbear JH, Winger G, Woods JH. Self-administration of fentanyl, cocaine and ketamine: effects on the pituitary-adrenal axis in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1891-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Siegler IC, Kuhn CM, Surwit RS, Garrett ME, Collins A, Shley-Koch A, Williams RB. HPA axis function in male caregivers: effect of the monoamine oxidase-A gene promoter (MAOA-uVNTR) Biol Psychol. 2008;79:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Mason WA, Maninger N. Rearing environment and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation in young rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Dev Psychobiol. 2005;46:318–330. doi: 10.1002/dev.20067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Curtis GC, Mendels J. Neuroendocrine regulation in depression. II. Discrimination of depressed from nondepressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1051–1058. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090041003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux M, Bennett A, Shannon C, Higley JD, Lesch KP, Suomi SJ. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism, differential early rearing, and behavior in rhesus monkey neonates. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:1058–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GL, Miller GM. Rhesus monkey tryptophan hydroxylase-2 coding region haplotypes affect mRNA stability. Neuroscience. 2008;155:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GL, Novak MA, Hakim S, Xie Z, Miller GM. Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene polymorphisms in rhesus monkeys: association with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and in vitro gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:914–928. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MC, Joormann J, Hallmayer J, Gotlib IH. Serotonin transporter polymorphism predicts waking cortisol in young girls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GL, Novak MA, Meyer JS, Kelly BJ, Vallender EJ, Miller GM. The effect of rearing experience and TPH2 genotype on HPA axis function and aggression in rhesus monkeys: a retrospective analysis. Horm Behav. 2010a;57:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GL, Novak MA, Meyer JS, Kelly BJ, Vallender EJ, Miller GM. TPH2 5′- and 3′-regulatory polymorphisms are differentially associated with HPA axis function and self-injurious behavior in rhesus monkeys. Genes Brain Behav. 2010b;9:335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MA, Kim PJ, Kalman BA, Spencer RL. Dexamethasone suppression of corticosteroid secretion: evaluation of the site of action by receptor measures and functional studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:151–167. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Matelli M, Luppino G, Zilles K. Functional neuroanatomy of the primate isocortical motor system. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2000;202:443–474. doi: 10.1007/s004290000127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RA, Rogers J, Katze MG, et al. Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:222–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie CF, Phifer J, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. Risk and resilience: genetic and environmental influences on development of the stress response. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:984–992. doi: 10.1002/da.20605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE. The impact of stress on addiction. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Bacon A, Ban M, Croudace T, Herbert J. Serotonin transporter genotype, morning cortisol and subsequent depression in adolescents. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:39–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman R, Yehuda R, New A, Schmeidler J, Silverman J, Mitropoulou V, Sta MN, Golier J, Siever L. Dexamethasone suppression test findings in subjects with personality disorders: associations with posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1291–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Bradley B, Mletzko TC, Deveau TC, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Ressler KJ, Binder EB. Effect of childhood trauma on adult depression and neuroendocrine function: sex-specific moderation by CRH receptor 1 gene. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:41. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.041.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Avila CA, Covault J, Wand G, Zhang H, Gelernter J, Kranzler HR. Population-specific effects of the Asn40Asp polymorphism at the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) on HPAaxis activation. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:1031–1038. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f0b99c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H, Ozeki Y, Teraishi T, Matsuo J, Kawamoto Y, Kinoshita Y, Suto S, Terada S, Higuchi T, Kunugi H. Relationships between psychological distress, coping styles, and HPA axis reactivity in healthy adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:865–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbi M, Korf J, Kema IP, Hartman C, van der Pompe G, Minderaa RB, Ormel J, den Boer JA. Convergent genetic modulation of the endocrine stress response involves polymorphic variations of 5-HTT, COMT and MAOA. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:483–490. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, Sapolsky R. The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocr Rev. 1991;12:118–134. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Gianaros PJ, Greer PJ, Kerr DD, Liu S, Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Olsen AS, Porter JN, Lopresti BJ, Hariri AR, Bradberry CW. Cognitive impact of genetic variation of the serotonin transporter in primates is associated with differences in brain morphology rather than serotonin neurotransmission. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:446. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Acute behavioral stress affects the dexamethasone suppression test in rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry. 1984;19:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Cohen RM, Kraemer GW, Risch SC, Shelton S, Cohen M, McKinney WT, Murphy DL. The dexamethasone suppression test as ameasure of hypothalamic-pituitary feedback sensitivity and its relationship to behavioral arousal. Neuroendocrinology. 1981;32:92–95. doi: 10.1159/000123137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ. Role of the primate orbitofrontal cortex in mediating anxious temperament. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1134–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Geuze E, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, Westenberg HG. Assessment of HPA-axis function in posttraumatic stress disorder: pharmacological and non-pharmacological challenge tests, a review. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:550–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Duran NL, Kovacs M, George CJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation in depressed children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkoski SP, Dorin RI. Composite glucocorticoid regulation at a functionally defined negative glucocorticoid response element of the human corticotropin-releasing hormone gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1629–1644. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.10.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack K, Newman TK, Higley JD, Maestripieri D, Sanchez MM. Serotonin transporter gene variation, infant abuse, and responsiveness to stress in rhesus macaque mothers and infants. Horm Behav. 2009;55:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. Research review: the neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:1079–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocoricoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GM, Bendor J, Tiefenbacher S, Yang H, Novak MA, Madras BK. A mu-opioid receptor single nucleotide polymorphism in rhesus monkey: association with stress response and aggression. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:99–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman TK, Syagailo YV, Barr CS, Wendland JR, Champoux M, Graessle M, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Lesch KP. Monoamine oxidase A gene promoter variation and rearing experience influences aggressive behavior in rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3:97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara R, Schroder CM, Mahadevan R, Schatzberg AF, Lindley S, Fox S, Weiner M, Kraemer HC, Noda A, Lin X, Gray HL, Hallmayer JF. Serotonin transporter polymorphism, memory and hippocampal volume in the elderly: association and interaction with cortisol. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:544–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen D, Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Maternal adversity, glucocorticoids and programming of neuroendocrine function and behaviour. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace TW, Spencer RL. Disruption of mineralocorticoid receptor function increases corticosterone responding to a mild, but not moderate, psychological stressor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E1082–E1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00521.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WM, Davidson D. Role of the HPA axis and the A118G polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor in stress-induced drinking behavior. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:358–365. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Kaplan J, Garcia R, Shelledy W, Nair S, Cameron J. Mapping of the serotonin transporter locus (SLC6A4) to rhesus chromosome 16 using genetic linkage. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;112:341A. doi: 10.1159/000089891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MM. The impact of early adverse care on HPA axis development: nonhuman primate models. Horm Behav. 2006;50:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuld A, Birkmann S, Beitinger P, Haack M, Kraus T, Dalal MA, Holsboer F, Pollmacher T. Low doses of dexamethasone affect immune parameters in the absence of immunological stimulation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114:322–328. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt ML, Lindell SG, Sjoberg RL, Chisholm KL, Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Heilig M, Barr CS. Gene-environment interactions and response to social intrusion in male and female rhesus macaques. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt ML, Lindell SG, Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Heilig M, Barr CS. OPRM1 gene variation influences hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in response to a variety of stressors in rhesus macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1303–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh YS, Sawarynski LE, Michael HM, Ferrell RE, Murphey-Corb MA, Swain GM, Patel BA, Andrews AM. Boron-doped diamond microelectrodes reveal reduced serotonin uptake rates in lymphocytes from adult Rhesus monkeys carrying the short allele of the 5-HTTLPR. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:49–64. doi: 10.1021/cn900012y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohle A, Scheel M, Modell S, Holsboer F. Blunted ACTH response to dexamethasone suppression-CRH stimulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:1185–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Price LH, Gelernter J, Schepker C, Anderson GM, Carpenter LL. Interaction of childhood maltreatment with the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene: effects on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E, Mittal V, Tessner K. Stress and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:189–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand GS, McCaul M, Yang X, Reynolds J, Gotjen D, Lee S, Ali A. The mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphism (A118G) alters HPA axis activation induced by opioid receptor blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:106–114. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland JR, Hampe M, Newman TK, Syagailo Y, Meyer J, Schempp W, Timme A, Suomi SJ, Lesch KP. Structural variation of the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter repeat polymorphism in nonhuman primates. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:40–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingenfeld K, Nutzinger D, Kauth J, Hellhammer DH, Lautenbacher S. Salivary cortisol release and hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis feedback sensitivity in fibromyalgia is associated with depression but not with pain. J Pain. 2010;11:1195–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt SH, Buchmann AF, Blomeyer D, Nieratschker V, Treutlein J, Esser G, Schmidt MH, Bidlingmaier M, Wiedemann K, Rietschel M, Laucht M, Wust S, Zimmermann US. An interaction between a neuropeptide Y gene polymorphism and early adversity modulates endocrine stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wust S, Kumsta R, Treutlein J, Frank J, Entringer S, Schulze TG, Rietschel M. Sex-specific association between the 5-HTT gene-linked polymorphic region and basal cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:972–982. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R. Sensitization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;821:57–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Halligan SL, Golier JA, Grossman R, Bierer LM. Effects of trauma exposure on the cortisol response to dexamethasone administration in PTSD and major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:389–404. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Variable length alleles at the rh5-HTTLPR and rhMAOA-LPR loci. (a) Two individuals with short/long (S/L) and long/extra long (L/XL) rh5-HTTLPR genotypes are shown. (b) Four individuals with 4, 5, 6 and 7 copy alleles at rhMAOA-LPR are shown.