Abstract

The activation and stabilization of the p53 protein play a major role in the DNA damage response. Protein levels of p53 are tightly controlled by transcriptional regulation and a number of positive and negative posttranslational modifiers, including kinases, phosphatases, E3 ubiquitin ligases, deubiquitinases, acetylases and deacetylases. One of the primary p53 regulators is Mdmx. Despite its RING domain and structural similarity with Mdm2, Mdmx does not have an intrinsic ligase activity, but inhibits the transcriptional activity of p53. Previous studies reported that Mdmx is phosphorylated and destabilized in response to DNA damage stress. Three phosphorylation sites identified are Ser342, Ser367, and Ser403. In the present study, we identify protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) as a negative regulator in the p53 signaling pathway. PP1 directly interacts with Mdmx and specifically dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367. The dephosphorylation of Mdmx increases its stability and thereby inhibits p53 activity. Our results suggest that PP1 is a crucial component in the ATM-Chk2-p53 signaling pathway.

Keywords: Protein phosphatase 1, p53, Mdmx, dephosphorylation, stabilization

1. Introduction

Genomic DNA of eukaryotic cells is under the constant attack of chemicals, free radicals, and UV or ionizing radiation from environmental exposure, by-products of intracellular metabolism, or medical therapy. The DNA damage response in cells translate DNA damage signal to responses of cell cycle arrest, DNA repair or apoptosis. A central component of the DNA damage response is tumor suppressor p53 [1, 2]. P53 is a transcription factor and serves as a pivotal tumor suppressor in animals. More than 50 percent of human tumors contain a mutation or deletion of the TP53 gene [3]. Upon DNA damage, the p53 tumor suppressor is activated to direct a transcriptional program that prevents the proliferation of genetically unstable cells. Inappropriate regulation of p53 results in a severe consequence for cells. While the loss of p53 function predisposes cells to tumorigenesis, errant p53 activation can lead to premature senescence or apoptosis.

An exquisite control mechanism prevents errant activation of p53 in cells. Central to this mechanism is the negative regulation exerted by Mdm2 and Mdmx (or Mdm4) [4]. Mdm2 is a RING domain containing E3 ubiquitin ligase that facilitates the ubiquitination of p53. Once poly-ubiquitinated, p53 is subject to proteasome-dependent degradation. Interestingly, p53 not only transcriptionally regulates genes involved in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, but also its own negative regulator, Mdm2. Thus, p53 and Mdm2 participate in an auto-regulatory feedback loop [5]. Mdmx was identified as a p53-binding protein that has structural similarity with Mdm2, but lacked ubiquitin-ligase function. Similar to Mdm2, Mdmx deficiency in mice causes early embryonic lethality rescued by p53 loss [6]. Thus, Mdmx and Mdm2 have non-redundant roles in the regulation of p53. Recent in vitro and in vivo studies suggested that Mdm2 mainly controls p53 stability, whereas Mdmx functions as an important p53 transcriptional inhibitor [7, 8].

In stressed cells, p53 is activated through mitigating the inhibitory activity of Mdm2 and Mdmx. A major mechanism that leads to the activation of p53 was purported to be the post-transcriptional modifications of p53 such as phosphorylation and acetylation that prevent Mdm2 from binding to or ubiquitinating p53 [9]. Many phosphorylation sites are located in the N-terminus of p53 that is adjacent to or overlapping with its Mdm2 binding domain, which may interfere with p53-Mdm2 interaction [10]. However, data from knockin p53 mutant mouse models as well as the observation that p53 does not have to be phosphorylated to be activated in cells have challenged the biological effects of phosphorylation events for p53. Mice expressing endogenous p53 mutated at the murine equivalents of serine 15 or 20 have only mild effects in p53 activity and stability, which is contrary to the predictions from the in vitro studies suggesting that serine 15 and threonine 18 phosphorylation prevented the negative regulation of p53 by Mdm2 [11, 12]. Whereas phosphorylation of p53 may fine-tune its function under various physiological contexts, an alternative view was brought up in which p53 regulation primarily depends on Mdm2 and Mdmx.

Mdm2 and Mdmx have also been phosphorylated in the DNA damage response. Oren et al first reported that Mdm2 undergoes ATM-dependent phosphorylation at Ser395 in response to ionizing radiation and radiomimetic drugs [13]. We previously showed that Mdm2 has reduced stability and accelerated degradation in the presence of Ser395 phosphorylation [14]. Mdmx is also phosphorylated and destabilized after DNA damage. Three phosphorylation sites have been identified on Mdmx, which are Ser342, Ser367 and Ser403 [15–17]. While Ser403 is directly phosphorylated by ATM, the other two sites are phosphorylated by Chk1 and Chk2, two crucial kinases that are activated by ATM/ATR and in turn initiate cell cycle checkpoints [18–21]. ATM-mediated phosphorylation destabilizes Mdmx and promotes their auto-degradation, which facilitates rapid p53 induction.

Opposed to protein kinases, protein phosphatases may play active roles in modulating the p53 signaling. The Prives group reported that cyclin G recruited PP2A to dephosphorylate Mdm2. Disruption of cyclin G leads to the hyperphosphorylation of Mdm2 and a higher level of p53 [22]. The specific B regulatory subunit of PP2A B56γ was identified to be associated with p53 in vivo and responsible for Thr55 dephosphorylation [23]. We and other groups identified Wip1 as a master inhibitor in the ATM-p53 pathway [24]. Three of the Wip1 targets in the pathway are kinases that phosphorylate and activate p53 (Chk1, Chk2, and p38 MAP kinase) [25–27]. We have also shown that Wip1 dephosphorylates Mdm2 and Mdmx at their ATM phosphorylation sites (Ser395 on Mdm2 and Ser403 on Mdmx). Unphosphorylated forms of Mdm2 and Mdmx have increased stability and affinity for p53, facilitating p53 degradation and deactivation. In the current study, we identify PP1 as the phosphatase that specifically dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367. The PP1-mediated dephosphorylation increases the stability of Mdmx and extends its half-life. Our results suggest that PP1 may serve as a homeostatic regulator in the p53 signaling pathway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and cell culture

U2OS (p53 wildtype) cell line is a human osteosarcoma line that was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Primary p53 Ala18/Ala and wildtype (p53 Ser18/Ser18) mouse embryonic fibroblasts were provided by Dr. Stephen Jones at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. They were harvested and cultured as previously described [28]. To obtain cells stably expressing Mdmx, expression vector expressing HA-tagged or FLAG-tagged wildtype or mutant human Mdmx was transfected into U2OS cells and stable cells were selected with 1000 µg/mL G-418. Positive colonies were isolated, amplified, and checked for expression of Mdmx protein individually.

2.2. Plasmid Constructs

Human serine/threonine phosphatase clones were purchased from ATCC and Open Biosystem. Full-length cDNA sequence of each phosphatase was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen). Human PP1γ expression vector was kindly provided by Dr. Sergei Nekhai (Howard University, Washington DC) and PPP5C was obtained from Dr. Xiaofan Wang (Duke University, NC). The p21-Luciferase was obtained from Dr. Gigi Lozano (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, TX). P53 consensus RE-luciferase and Mdm2-Luciferase constructs were provided by Dr. Lawrence Donehower (Baylor College of Medicine, TX). The vectors expressing wildtype and mutant Mdmx were previously described [29]. To express wildtype and mutant Mdmx proteins, full-length or mutant (point mutation and deleted mutation) Mdmx cDNA fragments were amplified by high-fidelity PCR from the above wildtype or mutant Mdmx expression vectors, and cloned into pGEX-4T-3 vector (GE Healthcare) as indicated in Fig. 4. GST-Mdmx fusion proteins were purified from crude Escherichia coli using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) column according to the manufacturer’s protocol and detected by Western blotting. PP1 shRNA expression vectors were purchased from Openbiosystems and the ShRNA and ORFeome Core at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

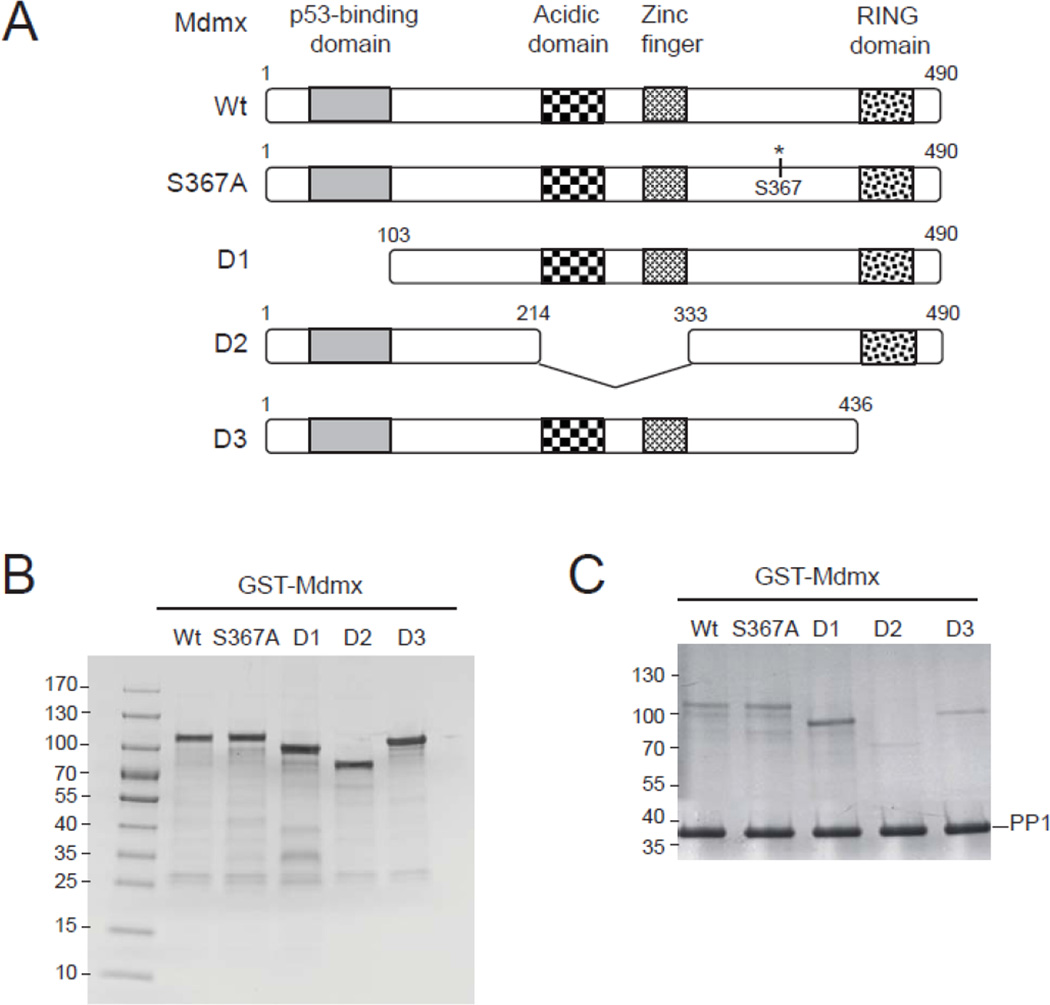

Figure 4.

PP1 directly interacts with Mdmx in vitro. (A) Schematic illustration for wildtype and mutant Mdmx. (B) Wildtype and mutant Mdmx with GST tag were expressed and purified from bacterial cell extracts. (C) In vitro Mdmx-PP1 interaction assays were performed by mixing PP1α-bound beads with wildtype or mutant Mdmx. The Mdmx proteins that bound PP1 were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and shown with Coomassie Blue staining.

2.3. Cell Transfection with plasmid DNA

Cells were transfected with plasmid DNA by Lipofectamine and Plus reagents (for transformed cell lines, Invitrogen, catalog # 18324-012 and #11514-015) or Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (for mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Invitrogen, catalog # 11668-019). Transfection experiments were performed following the instruction manuals provided with reagents.

2.4. Luciferase assays

Cells were cotransfected with phosphatase expression vector, p21-Luciferease vector (or p53RE-Luciferase and Wip1-Luciferase vectors), Renilla Luciferase vector. Cells were harvested at various time points and lysed. Luciferase activity was measured using a Turner 20/20n luminometer and normalized to Renilla luciferase according to the instructions provided with the dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega). Data are presented as the mean± standard deviation and are representative of three independent experiments.

2.5. Western blot analysis, antibodies, and purified proteins

Immunoprecipitations, Western blot analysis, and immunoprecipitation-Western blot analyses were performed by standard methods described previously [30]. Anti-actin (#1616), anti-ubiquitin (#8017), HRP-anti-goat IgG (#2020), HRP-anti-rabbit IgG (#2302), and HRP-anti-mouse IgG (#2302) were purchased from Santa Cruz; Anti-HA (A190-108A) and anti-Mdmx (#A300-287A) were purchased from Bethyl Laboratories; anti-Mdmx (pS403) and anti-Mdmx (pS367) were provided by Dr. Yosef Shiloh (Tel Aviv University, Isreal) and Dr. Jiandong Chen (Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, FL). They were generated and described previously [31, 32]. FLAG-tagged PP1 proteins were immunopurified using anti-FLAG beads (Sigma-Aldrich). PP2A proteins (#14-111) and PP1α proteins (#14-595) used for in vitro binding assays were purchased from EMD Millipore.

2.6. Protein stability measurement

Cell stably expressing wildtype or mutant HA-Mdmx were transfected with PP1 or control expression vector DNA. Twenty four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 500 ng/ml NCS and 50 µg/ml cycloheximide. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points after treatment, and cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Levels of Mdmx at each time point were quantitated by phosphorimager for Mdmx bands on immunoblots.

2.7. In vitro phosphatase assays

The in vitro phosphatase assays and control peptide sequences have been described previously [33]. Mdmx and control phosphopeptides were custom synthesized by New England Peptide. Their sequences are: Mdmx (pS342): Ac-LTHSLpSTSDIT-amide; Mdmx(pS367): Ac-CRRTIpSAPVVR-amide; Mdmx (pS403): Ac-AHSSEpSQETIS-amide; Chk1 (pS345): Ac-QGISFpSQPTCPD; negative control phospeptide: RHFSKpTNELLQ.

2.8. Ubiquitination assays

Cells were treated with proteasome inhibitors MG101 (25 µM) and MG132 (25 µM). Six hours after treatment, cells were harvested and lysed in the lysis buffer (20mM HEPES, pH7.4, 240 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5% TritonX-100, 1mM PMSF, 1mM DTT and Complete Mini protease inhibitor tablet from Roche). Ubiquitinated Mdmx were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, and then were Western blot analyzed with anti-ubiquitin antibody.

3. Results

3.1. Protein phosphatase 1 inhibits p53 signaling

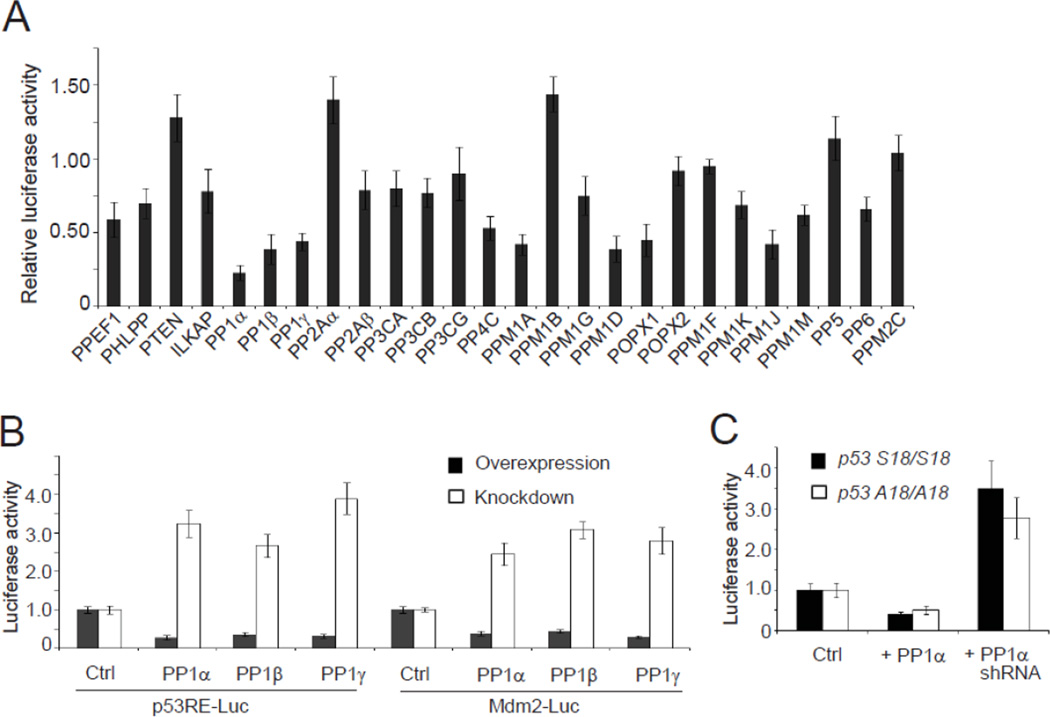

In contrast to kinases, the complexity of protein phosphatases and the lack of available reagents have made the identification and assignment of phosphatase function more challenging. Given the critical role of protein phosphorylation in the p53 signaling pathway, we attempted to identify novel serine/threonine phosphatases that regulate the pathway using a human expression library including 26 serine/threonine protein phosphatases (or catalytic subunits if multimeric) (Fig. 1A). Human U2OS cells were transfected with control or phosphatase expression vector along with p21 promoter-driven luciferase vector for detection of p53 activity. To induce p53 activity, cells were treated with a radiomimetic DNA-damaging agent, neocarzinostatin (NCS). 7 of the 26 phosphatases were shown to inhibit p53 activity (> 2-fold) in the screen, including PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ, PPM1A, PPM1D, POPX1 and PPM1J. Two protein phosphatases, PPM1B and PP2Aα, appeared to up-regulate p53 at marginal levels (~50%). Interestingly, three PP1 isoforms had similar inhibitory effects, indicating an important role of PP1 in regulating p53 activity. To further validate the effects of the three PP1 isoforms, we performed the luciferase assays using luciferase expression constructs driven by the consensus p53 responsive element or the promoter of Mdm2 gene that is another known target of p53 (Fig. 1B). Overexpression of each PP1 isoform inhibited p53 transcriptional activity in both luciferase constructs, whereas knockdown of PP1 by specific shRNAs significantly increased the p53 activity. A previous study has shown that Ser15 phosphorylation of p53 is induced after DNA damage and PP1α reverses this phosphorylation [34]. Due to high level of identity among the three PP1 isoforms, we speculated that PP1 may inhibit p53 activity through direct dephosphorylation of Ser15 in the DNA damage response. Therefore, we examined if the inhibitory effect of PP1 retains in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) carrying a Ser to Ala mutation at Ser18 (equivalent to human Ser15) on p53 (Fig. 1C). Consistent with the previous report that endogenous basal levels and DNA damage-induced levels of p53 were not affected by p53 Ser18 mutation [35], we found that PP1α retained its inhibitory effect on p53 in both wildtype (p53 Ser18/Ser18) and mutant (p53 Ala18/Ala18) MEFs in a similar pattern. These results suggest that the effect of PP1 is independent of the Ser15 phosphorylation of p53 (or Ser18 in mouse p53).

Figure 1.

PP1 inhibits the p53 signaling pathway. (A) The effects of overexpressed Ser/Thr protein phosphatases on the transcriptional activity of p53. U2OS cells were transfected with empty vector or phosphatase expression vector. 24 hr after transfection, cells were treated by NCS (500 ng/ml) and then harvested 12 hr after treatment. The relative luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the Renilla activity. Error bars indicate ± standard deviation in triplicate experiments. (B) PP1 inhibits the activity of p53. U2OS cells were transfected with p53RE-Luciferase or Mdm2-Luciferase vector, and expression vector encoding PP1 catalytic subunits or PP1 shRNAs. Cell lysates were harvested 12 h after NCS (500 ng/ml) treatment. Relative luciferase activity was determined as above. (C) Inhibition of p53 by PP1α is independent of Ser15 phosphorylation. p53 S18/S18 and p53 A18/A18 MEFs were transfected with control vector or vector expressing PP1α or PP1 shRNAs. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with NCS (500 ng/ml) and harvested 12h after treatment. Relative luciferase activity was determined as above.

3.2. PP1 augments Mdmx stability after DNA damage

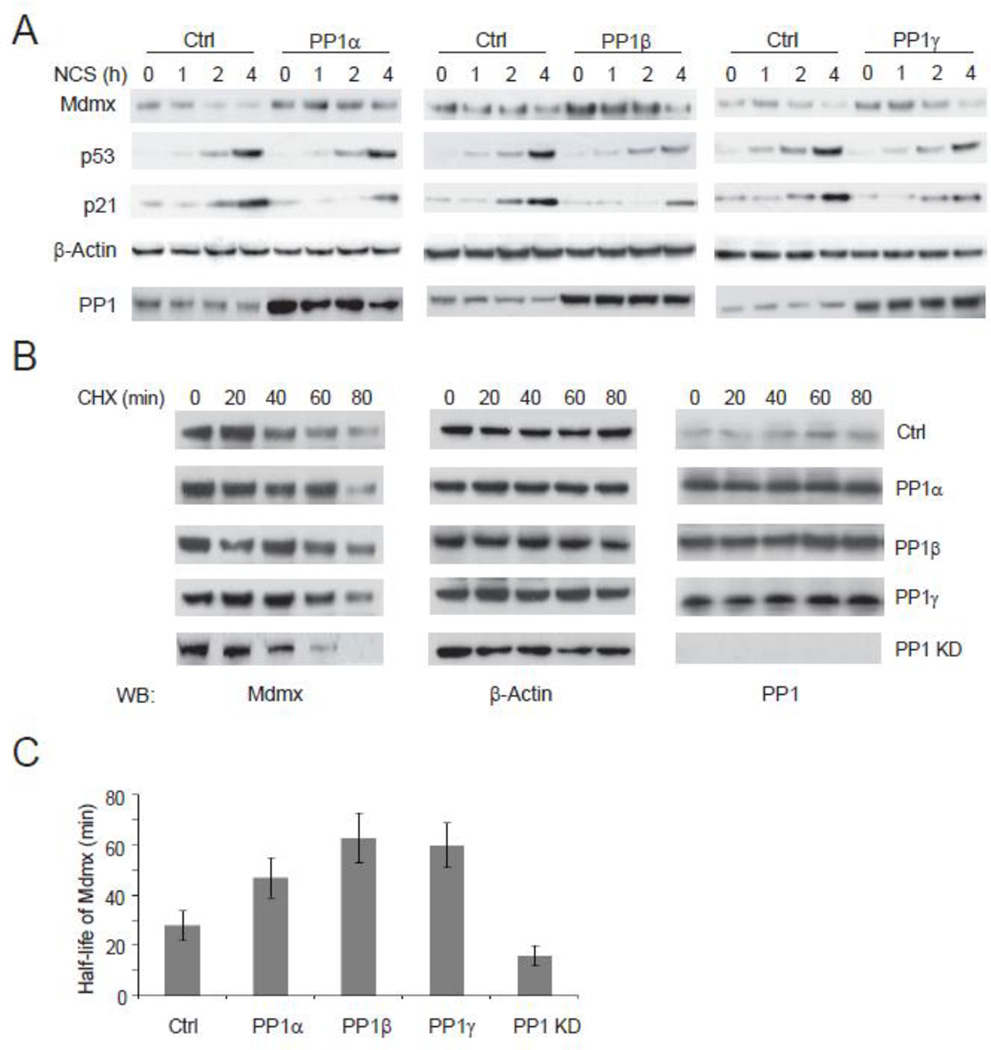

Two central regulators of the p53 activity are Mdm2 and Mdmx. Mdm2 is the primary determinant of p53 stability and abundance, whereas Mdmx is needed to antagonize p53-dependent transcriptional control [36, 37]. In response to DNA damage, Mdmx is phosphorylated by ATM, Chk1, Chk2 and other kinases [38, 39]. The phosphorylation of Mdmx destablizes Mdmx and leads to the induction of p53 activity [40]. We measured the DNA damage-induced level and activity of p53 in human U2OS cells overexpressing each individual PP1 isoform (Fig. 2A). While only slight changes on the level of p53 were observed, transcriptional activity of p53 (indicated by p21 levels) was significantly reduced in the PP1-overexpressing cells, suggesting a primary transcriptional inhibition of p53. Marked increases of steady levels of Mdmx were seen in the PP1-overexpressing cells. Mdmx appeared to be stabilized by overexpression of PP1. We next examined the effect of PP1 on the half-life of Mdmx (Fig. 2B). Overexpressing each of PP1 isoforms substantially extended the half-life of Mdmx in the NCS-treated cells. Mdmx had a half-life of ~ 29 min in the control cells treated with NCS, but it increased to 48–63 min in the presence of overexpressed PP1 (Fig. 2C). Using a common shRNA that target all three PP1 isoforms, we silenced global levels of PP1 in the cell. In contrast to PP1 overexpression, knockdown of PP1 resulted in destabilized Mdmx with a shortened half-life of 15 min.

Figure 2.

PP1 inhibits the transcriptional activity of p53 by stabilizing Mdmx. (A) PP1 stabilizes Mdmx in the DNA damage response. U2OS cells stably overexpressing PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ or common PP1 shRNAs were treated with NCS (500 ng/ml). Protein levels were detected by immunoblotting at the indicated time points. (B) PP1 upregulates the half-life of Mdmx. U2OS cells stably overexpressing PP1α, PP1β, or PP1γ were treated with NCS (500 ng/ml) and cyclohexamide (CHX, 50 µg/ml) to inhibit nascent protein synthesis. Protein levels of Mdmx, PP1 and β-actin were measured by immunoblotting. (C) Levels of Mdmx at each time point in B were quantitated and half-life of Mdmx was calculated (from two separate experiments).

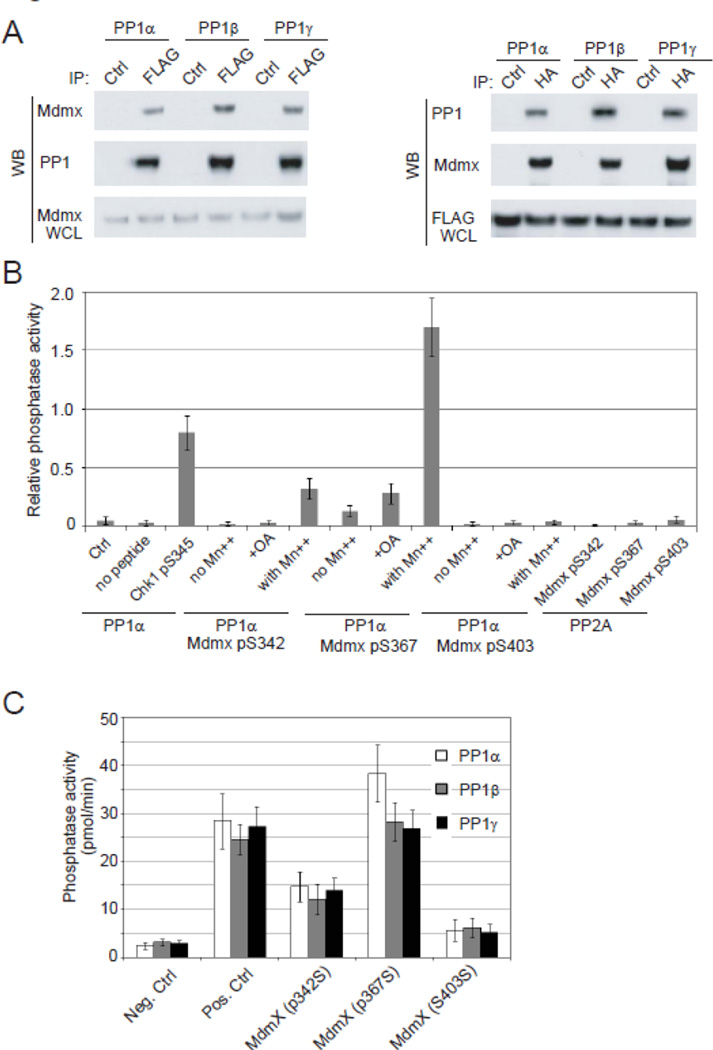

3.3. PP1 binds to Mdmx and dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367

We next examined whether PP1 enzymes were directly associated with Mdmx. The interaction between PP1 and Mdmx was tested in the reciprocal immunoprecipitation-Western blot analyses (Fig. 3A). We detected Mdmx in the FLAG-PP1 immunoprecipitates, while control IgG did not pull down Mdmx. Vice versa, each of three PP1 isoforms was also detected in the HA-Mdmx immunoprecipitates. These result suggested that Mdmx may be a substrate of PP1. To date, three phosphorylation sites on Mdmx have been identified: Ser342, Ser367, and Ser403. We further examined whether PP1 directly dephosphorylates Mdmx (Fig. 3B). In vitro phosphatase assays were first performed by incubating purified PP1α proteins with Mdmx-derived phospho-peptides containing each of the identified phosphorylation sites. As a positive control, PP1α dephosphorylated Chk1 at Ser345 that is phosphorylated by ATR [41]. Among the three Mdmx phosphorylation sites, the Mdmx Ser367 phosphopeptide was dephosphorylated by PP1α, and the PP1α activity on this phosphopeptide was manganese dependent and was sensitive to okadaic acid, a specific inhibitor for PP1/PP2A. PP1α also showed minimal activity on Mdmx pSer342, but no activity on the pSer403, which was previously identified as a Wip1 (or PPM1D) target in the laboratory. We also tested the activity of the other two PP1 isoforms on the phosphorylated Mdmx peptides (Fig. 3C). Similar to PP1α, PP1β and PP1γ exhibited a high dephosphorylation activity on Mdmx pSer367, suggesting that Ser367 may be a major dephosphorylation site of PP1 enzymes. To determine the direct Mdmx-PP1 interaction and the binding requirements, we perform direct binding assays using bacterial purified Mdmx and PP1α proteins (Fig. 4). S367A mutant Mdmx has a similar PP1-binding activity as wildtype Mdmx, suggesting that Ser367 phosphorylation of Mdmx does not contributes to the PP1-Mdmx interaction. Deleting N-terminal p53-binding domain or C-terminal RING domain on Mdmx only slightly influenced PP1’s binding. However, deleting the acidic domain and zinc finger domain in the middle of Mdmx dramatically blocked the PP1’s binding. The results indicate that the PP1-Mdmx interaction is independent of p53-Mdmx interaction.

Figure 3.

PP1 interacts with and dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367. (A) Three PP1isoforms interact with Mdmx. U2OS cells were transfected with vector expressing HA-Mdmx and FLAG-tagged PP1α, PP1β or PP1γ. Immunoprecipitates suing control or anti-FLAG antibody were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody (left panel). A reciprocal experiment using HA-PP1-containing immunoprecipitates confirmed the PP1-Mdmx interaction (right panel). WB: Western blot; WCL: whole cell lysate. (B) PP1α directly dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367, but not at Ser403 and Ser342. Phosphopeptides from Chk1 (pS345, positive control) and Mdmx containing phosphorylated Ser342, Ser367 or Ser403 were incubated with immunopurified PP1α enzymes in in vitro phosphatase assays. Reactions were also performed in the absence of manganese or peptide, or in the presence of okadaic acid. (C) All of three PP1 isoforms have similar phosphatase activity on Mdmx. Control peptides (negative control and positive Chk1 pS345 control) and Mdmx phosphopeptides were incubated with immunopurified PP1α, PP1β or PP1γ in the in vitro phosphatase assays. Phosphatase activity was calculated according to a phosphate standard curve.

To determine if PP1 dephosphorylates Mdmx Ser367 in vivo, we examined the phosphorylation of Mdmx in human U2OS cells overexpressing PP1 isoforms or the general PP1 shRNA (Fig. 5). We observed that overexpression of PP1α, β or γ isoform inhibits the DNA damage-induced Mdmx phosphorylation at Ser367, but not at Ser403, and that knockdown of PP1 greatly enhanced the Ser367 phosphorylation, suggesting that Mdmx pSer367 is an authentic substrate of PP1. Our results also showed that the three PP1 isoforms probably have redundant biochemical activity due to their high level of sequence identity among each other.

Figure 5.

PP1 dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367 in vivo. U2OS cells stably overexpressing PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ or common PP1 shRNAs were treated with or without NCS (500 ng/ml). The cells were harvested 4 h after treatment and cell lysates were subject to immunoblotting analyses using antibodies as indicated.

3.4. PP1 stabilization of Mdmx is dependent on the phosphorylation of Mdmx

The catalytic subunit of PP1 can from complexes with various regulatory subunits and functions in a number of biological processes. To determine if PP1 affects the stability of Mdmx primarily through dephosphorylation of Ser367, we examined the destabilization of wildtype and S367A mutant Mdmx in control and PP1α-overexpressing cells after NCS treatment (Fig. 6A). Overexpression of PP1α significantly inhibited the DNA damage-induced destabilization of wildtype Mdmx. However, mutating Ser367 to Ala abolished the effect of PP1α. While S367A mutant Mdmx was more stable than wildtype Mdmx, overexpression of PP1α had no impact on its destabilization. Half-life assays also showed a longer half-life of the mutant Mdmx than that of wildtype Mdmx (Fig. 6B). Altering PP1 levels by overexpression or shRNA knockdown had no notable effects on the half-life of the S367A mutant. Previous study showed that Mdm2 is a critical E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets Mdmx for degradation in cells [42]. Indeed, we observed that PP1 negatively regulated the ubiquitination of wildtype Mdmx (Fig. 6C). Ubiquitination of the S367A mutant was barely detectable under the same conditions and knockdown of PP1 failed to stabilize the mutant Mdmx, which is consistent with the above stability assays. We postulated that phosphorylation of Mdmx may change its binding capacity to Mdm2. Phosphorylated form of Mdmx seems to be a preferable substrate for Mdm2 [43]. The interaction between Mdmx and the Mdm2-containing complex was markedly enhanced after DNA damage, resulting in Mdmx degradation. The protein binding assays also showed that phosphorylation of Mdmx enhances its recruitment to the Mdm2-containing complex after DNA damage (Fig. 6D). PP1α overexpression had minimal effect on the Mdm2-Mdmx interaction but dramatically inhibited this interaction after DNA damage, suggesting unphosphorylated form of Mdmx has weaker binding activity with the Mdm2 complex and is thus more stable. Further structural studies on their interactions shall provide a better understanding of PP1 functions.

Figure 6.

PP1 stabilizes wildtype Mdmx, but not the S367A mutant Mdmx. (A) PP1 inhibits destabilization of wildtype Mdmx, but not the S367A mutant. U2OS cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged wildtype or S367A mutant Mdmx were transfected with control or PP1α expression vector. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with NCS (500 ng/ml) and harvested at 0 and 2 h after treatment. Protein levels were detected by immunoblotting using antibodies as indicated. (B) Altered PP1 levels have no impact on the half-life of the S367A mutant Mdmx. U2OS cells stably overexpressing wildtype or S367A mutant Mdmx were transfected with control vector or vector expressing PP1α or PP1 shRNAs. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with NCS (500 ng/ml) and cyclohexamide (CHX, 50 µg/ml) to inhibit nascent protein synthesis. Protein levels of Mdmx were measured by immunoblotting and quantitated as in Fig. 2C. Half-lives of Mdmx were calculated from two separate experiments. (C) PP1 inhibits the ubiquitination of Mdmx. U2OS cells stably expressing HA-Mdmx and HA-Mdmx (S367A) were transfected with PP1α, PP1 shRNA, or control expression vector. Transfected cells were treated with NCS (200 ng/ml) and protease inhibitors MG132 and MG101, and harvested 4 h after NCS treatment. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and immunoblotted by anti-ubiquitin antibody. (D) Overexpression of PP1α inhibits Mdm2-Mdmx interaction in the DNA damage response. 293 HEK cells were transfected with HA-Mdmx and PP1α or control expression vector, treated with NCS (200 ng/ml), and harvested 2 h after treatment. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Mdm2 antibody. Mdmx in the immunoprecipitates and various proteins in whole cell lysate (WCL) were assessed by immunoblotting as indicated.

4. Discussion

The DNA damage response is a rapid, elaborate and synchronized event that involves many repair proteins and protein phosphorylation events [44]. As a central player in the DNA damage response, the tumor suppressor p53 needs to be under delicate control. A large body of research has identified molecular mechanisms by which p53 is activated and stabilized following DNA damage, among which destabilization of Mdm2 appears to be the major driving force to initiate p53 activation [45, 46]. Phosphorylation of Mdm2 at Ser395 by the ATM kinase is an early event that destabilizes Mdm2 and accelerates the p53 accumulation [47, 48]. Upon the completion of DNA repair, cells will return to the normal state, which requires a shutdown of the p53 signaling pathway. Our previous studies have shown that PPM1D dephosphorylates Mdm2 and significantly extends the half-life of Mdm2 [49]. Delayed onset of PPM1D induction in the DNA damage response facilitates the homeostatic regulation of p53 [50]. We also reported that PPM1D dephosphorylates Mdmx at the ATM-phosphorylated Ser403 [51]. This dephosphorylation stabilizes Mdmx and enhances its inhibitory effect on the transcriptional activity of p53. Equally important as Ser403 phosphorylation, Ser367 phosphorylation of Mdmx also significantly contributes to Mdmx destabilization in the DNA damage response. Chk1, Chk2, and Akt are the kinases that phosphorylate this site [52, 53]. However, it is not known whether and how Mdmx is dephosphorylated at this site. In the current study, we show that all of the three PP1 isoforms specifically dephosphorylate Mdmx on pSer367, but not on pSer342 and pSer403. This dephosphorylation increases the stability of Mdmx by inhibiting the Mdm2-Mdmx interaction and the ubiquitination of Mdmx.

In our screen for the p53 regulators, we did not find any protein phosphatase that significantly enhances the p53 activity. In addition to the three PP1 enzymes, four protein phosphatases in the PPM family exhibits profound inhibition on p53 activity, indicating an important role of the PPM enzymes in the regulation of p53. Compelling evidence has supported the functional role of PPM1D as a master inhibitor in the ATM-p53 signaling pathway [54]. Particularly, PPM1D indirectly inhibits the phosphorylation of Mdmx by dephosphorylating and inactivating upstream kinases such as ATM, Chk1 and Chk2 [55, 56]. However, it is unclear how PPM1A, PPM1F and PPM1J interact with the p53 signaling. PPM family members are implicated in the negative regulation of stress-activated protein kinase cascades. As an example, PPM1B (or PP2Cβ) inhibits TAK1-mediated MKK4 -JNK and MKK6-p38 signaling pathways by dephosphorylating TAK1 [57]. PPM1A was previously identified as a phosphatase for p38 MAPK that is assumed to activate p53 by phosphorylation [58]. A latest study reported that the ATM kinase phosphorylates Smad1 on S239, which disrupts Smad1 interaction with protein phosphatase PPM1A, leading to enhanced activation and upregulation of Smad1 [59]. Smad1 binds to p53 and prevent Mdm2 from p53 ubiquitination and degradation. In our laboratory, our next -step study is to test whether PPM1A, PPM1F and PPM1F directly dephosphorylates pSer342 of Mdmx.

Mdmx degradation is primarily mediated by Mdm2-dependent ubiquitination. Mdm2 interacts with Mdmx through their RING finger domains [60]. The results in the study showed that PP1 dephosphorylation inhibits the interaction of Mdm2 with Mdmx. Ser367 locates near the Zinc finger domain (300–345) and RING finger domain (438–489). Ser367 phosphorylation may lead to a structural change that dissociates Mdmx from Mdm2. In addition, ubiquitin specific peptidase 7 (USP7) reverses the Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination of Mdmx [61, 62]. This deubiquitination prevents Mdmx from the proteasome degradation. We previously showed that dephosphorylated Mdmx seems to be preferable substrate for USP7 [63]. Therefore, PP1 dephosphorylation may enhance the interaction of USP7 and Mdmx.

Each PP1 enzyme contains both a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit in vivo. The catalytic subunit is a 30-kD single-domain protein and forms complexes with a number of regulatory subunits [64]. The catalytic subunit is highly conserved among all eukaryotes, suggesting a common catalytic activity. The catalytic subunit can from complexes with various regulatory subunits. PP1 has crucial functions in glycogen metabolism, cell proliferation, RNA processing, apoptosis, protein synthesis, and regulation of membrane receptors and channels. Regulation of these different processes is facilitated by distinct regulatory subunits in the PP1 holoenzymes. A large number of PP1-interacting proteins (>100) have been identified so far [65–67]. Given there are approximately 10,000 phosphoproteins and many more phosphorylation sites in mammals, many regulatory subunits of PP1 remain to be discovered. Although PP1 is shown to inhibit the p53 signaling, a question remains to be answered is: how is PP1 activity regulated in the DNA damage response. No notable changes on global PP1 levels were observed after DNA damage (data not shown). We hypothesize that PP1 is inhibited at the early stage of the DNA damage response by one or more of its inhibitory regulators, thereby allowing p53 to be rapidly activated and accumulated. The PP1 inhibitory regulators may be suppressed by transcriptional or post-transcriptional mechanisms, resulting in activation of PP1 catalytic subunits. Further studies will identify these regulatory factors that contribute to the PP1 activity and specificity on Mdmx in the DNA damage response.

The inhibitory function of PP1 in the p53 signaling suggests that it may be a potential oncogene candidate. However, due to the complexity of its regulation and multifaceted functions, controversial results have been often shown in the literature. Gene mutations on the three PP1 catalytic subunits are rarely found in human cancer. We investigated the expression of PP1 isoforms in human breast and ovarian cancer. From our analysis of the TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) data, we indeed found that PP1 is globally overexpressed in these two types of cancer. 25%, 30% and 31% of human breast cancer samples were found to overexpress (log 2 >0.5) PP1α, PP1β and PP1γ, respectively. In ovarian cancer, 29%, 30% and 34% of the tumor samples overexpress PP1α, PP1β and PP1γ, respectively. Further studies on animal models and clinical samples will be needed to clearly identify the roles of PP1 in tumorigenesis.

Highlights.

Protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) inhibits the p53 signaling in the DNA damage response.

PP1 interacts with and dephosphorylates Mdmx at Ser367.

Dephosphorylation of Mdmx by PP1 stabilizes Mdmx.

PP1 inhibits Mdm2-Mdmx interaction in the DNA damage response.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lin Lin and Xianli Cui in the Lu laboratory for technical assistance. We are very grateful to Drs. Sergei Nekhai, Xiaofan Wang, Gigi Lozano, Jiandong Chen, Yosef Shiloh and Lawrence Donehower for providing the reagents. This work was supported by grants to X.L. from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA136549 and R03CA142605) and the American Cancer Society (119135-RSG-10-185-01-TBE).

Abbreviation

- PPM

protein phosphatase, magnesium-dependent

- MKK4

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4

- MKK6

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6

- JNK

c-Jun amino-terminal kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Appella E, Anderson CW. Signaling to p53: breaking the posttranslational modification code. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 2000;48:227–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benard J, Douc-Rasy S, Ahomadegbe JC. TP53 family members and human cancers. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:182–191. doi: 10.1002/humu.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marine JC, Dyer MA, Jochemsen AG. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:371–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parant J, Chavez-Reyes A, Little NA, Yan W, Reinke V, Jochemsen AG, Lozano G. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:92–95. doi: 10.1038/ng714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francoz S, Froment P, Bogaerts S, De CS, Maetens M, Doumont G, Bellefroid E, Marine JC. Mdm4 and Mdm2 cooperate to inhibit p53 activity in proliferating and quiescent cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:3232–3237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508476103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toledo F, Krummel KA, Lee CJ, Liu CW, Rodewald LW, Tang M, Wahl GM. A mouse p53 mutant lacking the proline-rich domain rescues Mdm4 deficiency and provides insight into the Mdm2-Mdm4-p53 regulatory network. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appella E, Anderson CW. Signaling to p53: breaking the posttranslational modification code. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 2000;48:227–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode AM, Dong Z. Post-translational modification of p53 in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:793–805. doi: 10.1038/nrc1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sluss HK, Armata H, Gallant J, Jones SN. Phosphorylation of serine 18 regulates distinct p53 functions in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:976–984. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.976-984.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacPherson D, Kim J, Kim T, Rhee BK, Van Oostrom CT, DiTullio RA, Venere M, Halazonetis TD, Bronson R, De VA, Fleming M, Jacks T. Defective apoptosis and B-cell lymphomas in mice with p53 point mutation at Ser 23. EMBO J. 2004;23:3689–3699. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maya R, Balass M, Kim ST, Shkedy D, Leal JF, Shifman O, Moas M, Buschmann T, Ronai Z, Shiloh Y, Kastan MB, Katzir E, Oren M. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Mdm2 on serine 395: role in p53 activation by DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1067–1077. doi: 10.1101/gad.886901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, Ma O, Nguyen TA, Jones SN, Oren M, Donehower LA. The Wip1 Phosphatase acts as a gatekeeper in the p53-Mdm2 autoregulatory loop. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 2005;24:3411–3422. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Y, Dai MS, Lu SZ, Xu Y, Luo Z, Zhao Y, Lu H. 14-3-3gamma binds to MDMX that is phosphorylated by UV-activated Chk1, resulting in p53 activation. EMBO J. 2006;25:1207–1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereg Y, Shkedy D, de GP, Meulmeester E, Edelson-Averbukh M, Salek M, Biton S, Teunisse AF, Lehmann WD, Jochemsen AG, Shiloh Y. Phosphorylation of Hdmx mediates its Hdm2- and ATM-dependent degradation in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:5056–5061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408595102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 2005;24:3411–3422. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto K, Kashima K, Pereg Y, Ishida M, Yamazaki S, Nota A, Teunisse A, Migliorini D, Kitabayashi I, Marine JC, Prives C, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG, Taya Y. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:9608–9620. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9608-9620.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereg Y, Shkedy D, de GP, Meulmeester E, Edelson-Averbukh M, Salek M, Biton S, Teunisse AF, Lehmann WD, Jochemsen AG, Shiloh Y. Phosphorylation of Hdmx mediates its Hdm2- and ATM-dependent degradation in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:5056–5061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408595102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin Y, Dai MS, Lu SZ, Xu Y, Luo Z, Zhao Y, Lu H. 14-3-3gamma binds to MDMX that is phosphorylated by UV-activated Chk1, resulting in p53 activation. EMBO J. 2006;25:1207–1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto K, Li H, Jensen MR, Zhang T, Taya Y, Thorgeirsson SS, Prives C. Cyclin G recruits PP2A to dephosphorylate Mdm2. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li HH, Cai X, Shouse GP, Piluso LG, Liu X. A specific PP2A regulatory subunit, B56gamma, mediates DNA damage-induced dephosphorylation of p53 at Thr55. EMBO J. 2007;26:402–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu X, Nguyen TA, Moon SH, Darlington Y, Sommer M, Donehower LA. The type 2C phosphatase Wip1: An oncogenic regulator of tumor suppressor and DNA damage response pathways. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimoto H, Onishi N, Kato N, Takekawa M, Xu XZ, Kosugi A, Kondo T, Imamura M, Oishi I, Yoda A, Minami Y. Regulation of the antioncogenic Chk2 kinase by the oncogenic Wip1 phosphatase. Cell Death. Differ. 2006;13:1170–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takekawa M, Adachi M, Nakahata A, Nakayama I, Itoh F, Tsukuda H, Taya Y, Imai K. p53-inducible wip1 phosphatase mediates a negative feedback regulation of p38 MAPK-p53 signaling in response to UV radiation. EMBO J. 2000;19:6517–6526. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu X, Nannenga B, Donehower LA. PPM1D dephosphorylates Chk1 and p53 and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1162–1174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sluss HK, Armata H, Gallant J, Jones SN. Phosphorylation of serine 18 regulates distinct p53 functions in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:976–984. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.976-984.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Lin L, Guo H, Yang J, Jones SN, Jochemsen A, Lu X. Phosphorylation and degradation of MdmX is inhibited by Wip1 phosphatase in the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7960–7968. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu X, Nannenga B, Donehower LA. PPM1D dephosphorylates Chk1 and p53 and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1162–1174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereg Y, Shkedy D, de GP, Meulmeester E, Edelson-Averbukh M, Salek M, Biton S, Teunisse AF, Lehmann WD, Jochemsen AG, Shiloh Y. Phosphorylation of Hdmx mediates its Hdm2- and ATM-dependent degradation in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:5056–5061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408595102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 2005;24:3411–3422. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu X, Bocangel D, Nannenga B, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Donehower LA. The p53-induced oncogenic phosphatase PPM1D interacts with uracil DNA glycosylase and suppresses base excision repair. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haneda M, Kojima E, Nishikimi A, Hasegawa T, Nakashima I, Isobe K. Protein phosphatase 1, but not protein phosphatase 2A, dephosphorylates DNA-damaging stress-induced phospho-serine 15 of p53. FEBS Lett. 2004;567:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sluss HK, Armata H, Gallant J, Jones SN. Phosphorylation of serine 18 regulates distinct p53 functions in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:976–984. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.976-984.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marine JC, Dyer MA, Jochemsen AG. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:371–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 2005;24:3411–3422. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okamoto K, Kashima K, Pereg Y, Ishida M, Yamazaki S, Nota A, Teunisse A, Migliorini D, Kitabayashi I, Marine JC, Prives C, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG, Taya Y. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:9608–9620. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9608-9620.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Lin L, Guo H, Yang J, Jones SN, Jochemsen A, Lu X. Phosphorylation and degradation of MdmX is inhibited by Wip1 phosphatase in the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7960–7968. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.den Elzen NR, O'Connell MJ. Recovery from DNA damage checkpoint arrest by PP1-mediated inhibition of Chk1. EMBO J. 2004;23:908–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan Y, Chen J. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:5113–5121. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5113-5121.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Lin L, Guo H, Yang J, Jones SN, Jochemsen A, Lu X. Phosphorylation and degradation of MdmX is inhibited by Wip1 phosphatase in the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7960–7968. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng Q, Cross B, Li B, Chen L, Li Z, Chen J. Regulation of MDM2 E3 ligase activity by phosphorylation after DNA damage. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;31:4951–4963. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05553-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maya R, Balass M, Kim ST, Shkedy D, Leal JF, Shifman O, Moas M, Buschmann T, Ronai Z, Shiloh Y, Kastan MB, Katzir E, Oren M. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Mdm2 on serine 395: role in p53 activation by DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1067–1077. doi: 10.1101/gad.886901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu X, Ma O, Nguyen TA, Jones SN, Oren M, Donehower LA. The Wip1 Phosphatase acts as a gatekeeper in the p53-Mdm2 autoregulatory loop. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu X, Ma O, Nguyen TA, Jones SN, Oren M, Donehower LA. The Wip1 Phosphatase acts as a gatekeeper in the p53-Mdm2 autoregulatory loop. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang X, Wan G, Mlotshwa S, Vance V, Berger FG, Chen H, Lu X. Oncogenic Wip1 phosphatase is inhibited by miR-16 in the DNA damage signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7176–7186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, Lin L, Guo H, Yang J, Jones SN, Jochemsen A, Lu X. Phosphorylation and degradation of MdmX is inhibited by Wip1 phosphatase in the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7960–7968. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okamoto K, Kashima K, Pereg Y, Ishida M, Yamazaki S, Nota A, Teunisse A, Migliorini D, Kitabayashi I, Marine JC, Prives C, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG, Taya Y. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:9608–9620. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9608-9620.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 2005;24:3411–3422. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu X, Nguyen TA, Moon SH, Darlington Y, Sommer M, Donehower LA. The type 2C phosphatase Wip1: An oncogenic regulator of tumor suppressor and DNA damage response pathways. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu X, Nannenga B, Donehower LA. PPM1D dephosphorylates Chk1 and p53 and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1162–1174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujimoto H, Onishi N, Kato N, Takekawa M, Xu XZ, Kosugi A, Kondo T, Imamura M, Oishi I, Yoda A, Minami Y. Regulation of the antioncogenic Chk2 kinase by the oncogenic Wip1 phosphatase. Cell Death. Differ. 2006;13:1170–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanada M, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Komaki K, Ohnishi M, Katsura K, Kanamaru R, Matsumoto K, Tamura S. Regulation of the TAK1 signaling pathway by protein phosphatase 2C. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5753–5759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanada M, Kobayashi T, Ohnishi M, Ikeda S, Wang H, Katsura K, Yanagawa Y, Hiraga A, Kanamaru R, Tamura S. Selective suppression of stress-activated protein kinase pathway by protein phosphatase 2C in mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;437:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chau JF, Jia D, Wang Z, Liu Z, Hu Y, Zhang X, Jia H, Lai KP, Leong WF, Au BJ, Mishina Y, Chen YG, Biondi C, Robertson E, Xie D, Liu H, He L, Wang X, Yu Q, Li B. A crucial role for bone morphogenetic protein-Smad1 signalling in the DNA damage response. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:836. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanimura S, Ohtsuka S, Mitsui K, Shirouzu K, Yoshimura A, Ohtsubo M. MDM2 interacts with MDMX through their RING finger domains. FEBS Lett. 1999;447:5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meulmeester E, Pereg Y, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG. ATM-mediated phosphorylations inhibit Mdmx/Mdm2 stabilization by HAUSP in favor of p53 activation. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1166–1170. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meulmeester E, Maurice MM, Boutell C, Teunisse AF, Ovaa H, Abraham TE, Dirks RW, Jochemsen AG. Loss of HAUSP-mediated deubiquitination contributes to DNA damage-induced destabilization of Hdmx and Hdm2. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, Lin L, Guo H, Yang J, Jones SN, Jochemsen A, Lu X. Phosphorylation and degradation of MdmX is inhibited by Wip1 phosphatase in the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7960–7968. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Virshup DM, Shenolikar S. From promiscuity to precision: protein phosphatases get a makeover. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flores-Delgado G, Liu CW, Sposto R, Berndt N. A limited screen for protein interactions reveals new roles for protein phosphatase 1 in cell cycle control and apoptosis. J. Proteome. Res. 2007;6:1165–1175. doi: 10.1021/pr060504h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Terrak M, Kerff F, Langsetmo K, Tao T, Dominguez R. Structural basis of protein phosphatase 1 regulation. Nature. 2004;429:780–784. doi: 10.1038/nature02582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Virshup DM, Shenolikar S. From promiscuity to precision: protein phosphatases get a makeover. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]