Abstract

Purpose

Building on previous research documenting differences in preventive care quality between cancer survivors and noncancer controls, this study examines comorbid condition care.

Methods

Using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) –Medicare database, we examined comorbid condition quality of care in patients with locoregional breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer diagnosed in 2004 who were age ≥ 66 years at diagnosis, who had survived ≥ 3 years, and who were enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare. Controls were frequency matched to cases on age, sex, race, and region. Quality of care was assessed from day 366 through day 1,095 postdiagnosis using published indicators of chronic (n = 10) and acute (n = 19) condition care. The proportion of eligible cancer survivors and controls who received recommended care was compared by using Fisher's exact tests. The chronic and acute indicators, respectively, were then combined into single logistic regression models for each cancer type to compare survivors' care receipt to that of controls, adjusting for clinical and sociodemographic variables and controlling for within-patient variation.

Results

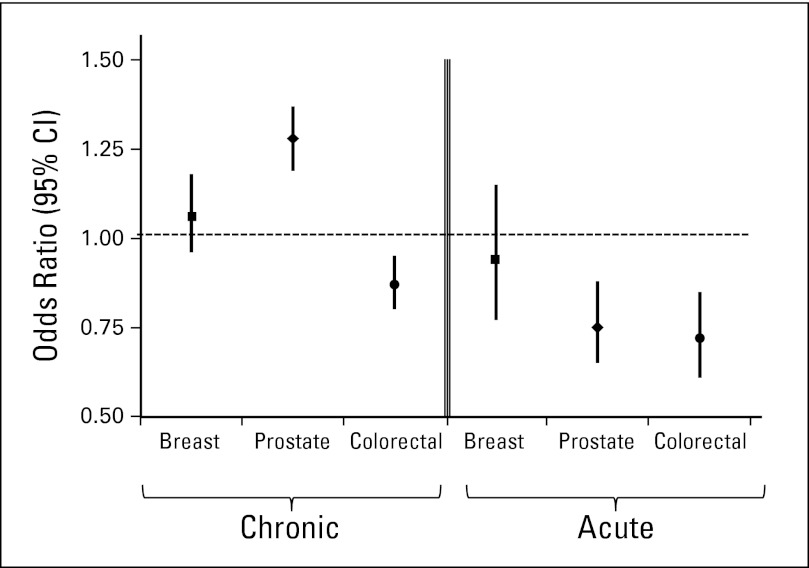

The sample matched 8,661 cancer survivors to 17,322 controls (mean age, 75 years; 65% male; 85% white). Colorectal cancer survivors were less likely than controls to receive appropriate care on both the chronic (odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.95) and acute (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.85) indicators. Prostate cancer survivors were more likely to receive appropriate chronic care (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.38) but less likely to receive quality acute care (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.87). Breast cancer survivors received care equivalent to controls on both the chronic (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.17) and acute (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.13) indicators.

Conclusion

Because we found differences by cancer type, research exploring factors associated with these differences in care quality is needed.

INTRODUCTION

The 2005 Institute of Medicine report “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition” highlights cancer survivors' health care needs, including surveillance for recurrence, treatment for long-term and late effects of cancer and its treatment, general primary and preventive care, and in many cases, care for comorbid conditions.1 In a population-based national sample, 58% of cancer survivors had at least one comorbid condition compared with 45% of noncancer controls2; thus, comorbid condition care is required in a majority of cancer survivors. The need for quality comorbid condition care will continue to increase as improvements in diagnosis and treatment lead to patients with cancer living longer after diagnosis. The 5-year relative survival for breast cancer is 90%, for prostate cancer is 100%, and for colorectal cancer is 65%.3 For cancers such as early-stage breast cancer, survivors are more likely to die from causes other than cancer.4 Although quality comorbid condition care is important for all cancer survivors, it is particularly relevant for older cancer survivors because they are more likely to have health problems in addition to their cancer. Sixty percent of survivors are older than age 65,5 and two thirds of the projected increase in annual cancer incidence between 2010 and 2030, from 1.6 to 2.3 million cases, is related to the aging of the population.6

Despite the importance of appropriate comorbid condition care for cancer survivors, few studies have examined this topic. Research has examined either particular comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes)7,8 or particular cancers.9–14 Earle and Neville15 examined comorbid condition care quality in 5-year colorectal cancer survivors diagnosed from 1991 to 1992 and found worse care in cancer survivors compared with noncancer controls, particularly for chronic conditions. Other research comparing the quality of cancer survivors' preventive care to that of controls has produced mixed results, depending on the type of cancer studied.16–21 In this study, we build on the previous research to investigate the quality of comorbid condition care in three kinds of cancer by using more recent data from patients with cancer who were transitioning from active treatment to survivorship. We examine a broad range of quality indicators for comorbid condition care to assess whether the prior research findings of differences in care by cancer type are further supported.

METHODS

Research Design

This retrospective cross-sectional study examined the quality of comorbid condition care in survivors of locoregional breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer and compared survivors' care to that of matched noncancer controls. These three cancer types represent approximately half of incident cancers3 and survivors.5 We focused on the period during which patients would be completing active cancer treatment and transitioning to survivorship. Specifically, we assumed that cancer treatment would occur in the first year following diagnosis; thus, our study period started on day 366 postdiagnosis and continued for 2 years through day 1,095. We identified cancer survivors with each comorbid condition and evaluated whether they received appropriate care by using published quality indicators.15,22 Survivors' care receipt was compared with that of noncancer controls in analyses for each cancer type separately.

Data Source

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) –Medicare linked database, which combines the clinical information from the SEER registries with Medicare claims. During our study period, there were 17 SEER registries covering a population-based sample of 26% of the US population,23 with 16 of the 17 registries participating in the Medicare linkage. Data on noncancer controls from a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries living in SEER regions were used for comparison.

Study Subjects

We identified patients diagnosed with locoregional breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer in the year 2004 who survived for at least 3 years. Patients had to be continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare from 1 year before diagnosis through 3 years after diagnosis, which means they had to be at least 66 years old at diagnosis. Patients enrolled in managed care at any point during the observation period were excluded. Thus, all patients were insured through the fee-for-service Medicare program. We used the claims data from before the cancer diagnosis to calculate the prediagnosis comorbidity score. Because we wanted to study patients who had completed acute treatment and had no evidence of disease, we excluded patients who had a subsequent malignant diagnosis or had received chemotherapy, radiation, or hospice care from day 366 through day 1,095.

Noncancer controls had to meet similar eligibility criteria, with the exception of a cancer diagnosis. We frequency matched controls 2:1 by using age (65-74, 75+ years), race (white, black, other), sex, and SEER region (combining Atlanta and rural Georgia, and combining all California registries). Controls were matched separately for each of the three tumor types to retain the frequency matching for analyses by tumor type. A dummy diagnosis date of January 1, 2004, was used for all controls.

Outcome Measures

We used nine chronic condition and 19 acute condition quality indicators (Table 1). There were also seven avoidable outcome indicators that were summarized in one chronic condition indicator: “no avoidable outcome.” Approximately half the chronic condition indicators related to ongoing visits, and approximately half the acute event indicators related to visits following a hospitalization. Other quality indicators included monitoring procedures such as eye examinations for patients with diabetes and tests such as ECGs. We used indicators based on those developed by RAND22 and later applied by Earle and Neville.15 Using these indicators allowed us to compare our findings in patients with one of three cancer types who were transitioning to survivorship with the previous findings in 5-year colorectal cancer survivors.15 Where necessary, we revised the quality indicators to reflect updated diagnosis and billing codes for our study period (see Appendix Table A1, online only, for the indicator specifications we used).

Table 1.

Quality Indicators

| Indicator |

|---|

Chronic care

|

Acute care

|

Analyses

First, survivors' and controls' clinical and sociodemographic data were described by using mean (standard deviation) for age and proportions for race, sex, SEER registry site, urban/rural residence, participation in state buy-in (an indicator of lower socioeconomic status), and the Charlson comorbidity score as modified by Deyo and implemented by Klabunde.24–26 This comorbidity score was measured by using precancer diagnosis claims for the purpose of developing a summary measure to include as a covariate. To identify cases and controls eligible for each quality indicator on the basis of the presence of a particular comorbid condition, we applied the algorithms in the technical document associated with the published quality indicators.22

Specifically, for the chronic condition indicators, we identified cases and controls with the chronic conditions by using claims from day 1 through day 365 from diagnosis (the denominator). We then examined whether appropriate care was provided during the observation period from day 366 through day 1,095 (the numerator). For the acute care indicators, we examined incident events from day 366 through day 1,095. For both the chronic and acute condition indicators, we calculated the percentage of cases and controls who received appropriate care and compared the two groups using Fisher's exact tests with a P < .05 threshold for statistical significance. Given the large number of indicators and comparisons, we then combined all chronic and acute condition indicators, respectively, into single generalized estimating equation logistic regression models for each cancer type, adjusting for age, race, sex (colorectal analysis only), SEER region, comorbidity score, state buy-in, and urban/rural residence. Generalized estimating equation models were used to account for clustering because patients who were eligible for more than one indicator were included in the model multiple times. Six models (acute and chronic for the three tumor types) were analyzed, and a Bonferonni correction was used such that P < .008 was considered statistically significant. Although the unadjusted tests comparing the individual indicators were performed to evaluate patterns in the data, the statistical tests of the models combining all indicators were considered the definitive tests of differences in care between cancer cases and controls by cancer type. Finally, we examined the interaction between each covariate and case-control group in the regression models. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board deemed this project exempt.

RESULTS

The final sample included 8,661 cancer cases and 17,322 controls. The sample included 4,559 prostate cancer survivors (53%), 2,231 colorectal cancer survivors (26%), and 1,871 breast cancer survivors (22%). Across the three cancer types, the mean age was 75 years; approximately two thirds of the sample was male, and 85% were white (Table 2). One third of the population was from one of the California registries. These characteristics were identical between cases and controls as a result of matching. For the nonmatched variables, we see approximately the same proportion of controls and cases with comorbidity scores of 0 (72% of controls v 71% of cases) and level of urban residence (88% of controls v 90% of cases). Slightly more controls than cases were in state buy-in (14% v 10%), indicating lower socioeconomic status.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Cancer Cases and Matched Controls

| Characteristic | Controls Overall (n = 17,322) |

Cases |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 8,661) |

Colorectal (n = 2,231) |

Breast (n = 1,871) |

Prostate (n = 4,559) |

|||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| Mean | 75.0 | 74.8 | 77.2 | 76.9 | 72.8 | |||||

| SD | 6.81 | 6.55 | 7.02 | 7.16 | 5.25 | |||||

| Male sex | 11,228 | 64.8 | 5,614 | 64.8 | 1,055 | 47.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4,559 | 100.0 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| White | 14,660 | 84.6 | 7,330 | 84.6 | 1,926 | 86.3 | 1,656 | 88.5 | 3,748 | 82.2 |

| Black | 1,442 | 8.3 | 721 | 8.3 | 149 | 6.7 | 113 | 6.0 | 459 | 10.1 |

| Other | 1,220 | 7.0 | 610 | 7.0 | 156 | 7.0 | 102 | 5.5 | 352 | 7.7 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 12,474 | 72.0 | 6,114 | 70.6 | 1,376 | 61.7 | 1,306 | 69.8 | 3,432 | 75.3 |

| 1+ | 4,848 | 28.0 | 2,547 | 29.4 | 855 | 38.3 | 565 | 30.2 | 1,127 | 24.7 |

| Ever in state buy-in | 2,388 | 13.8 | 883 | 10.2 | 280 | 12.6 | 245 | 13.1 | 358 | 7.9 |

| Urban residence | 15,272 | 88.4 | 7,824 | 90.3 | 1,963 | 88.0 | 1,679 | 89.7 | 4,182 | 91.7 |

| SEER region | ||||||||||

| Connecticut | 1,242 | 7.2 | 621 | 7.2 | 179 | 8.0 | 171 | 9.1 | 271 | 5.9 |

| Detroit | 1,172 | 6.8 | 586 | 6.8 | 156 | 7.0 | 112 | 6.0 | 318 | 7.0 |

| Hawaii | 262 | 1.5 | 131 | 1.5 | 37 | 1.7 | 19 | 1.0 | 75 | 1.7 |

| Iowa | 1,240 | 7.2 | 620 | 7.2 | 229 | 10.3 | 163 | 8.7 | 228 | 5.0 |

| New Mexico | 430 | 2.5 | 215 | 2.5 | 54 | 2.4 | 41 | 2.2 | 120 | 2.6 |

| Seattle | 1,266 | 7.3 | 633 | 7.3 | 119 | 5.3 | 130 | 7.0 | 384 | 8.4 |

| Utah | 712 | 4.1 | 356 | 4.1 | 62 | 2.8 | 56 | 3.0 | 238 | 5.2 |

| Atlanta and rural Georgia | 466 | 2.7 | 233 | 2.7 | 43 | 1.9 | 50 | 2.7 | 140 | 3.1 |

| California* | 5,810 | 33.5 | 2,905 | 33.5 | 662 | 29.7 | 581 | 31.1 | 1,662 | 36.5 |

| Kentucky | 1,158 | 6.7 | 579 | 6.7 | 177 | 7.9 | 138 | 7.4 | 264 | 5.8 |

| Louisiana | 1,144 | 6.6 | 572 | 6.6 | 118 | 5.3 | 137 | 7.3 | 317 | 7.0 |

| New Jersey | 2,420 | 14.0 | 1,210 | 14.0 | 395 | 17.7 | 273 | 14.6 | 542 | 11.9 |

Including greater California, San Francisco, San Jose, and Los Angeles registries.

Table 3 presents the performance on the 10 chronic condition indicators for the cases and controls overall and by tumor type. In the analysis combining all three tumor types, the differences tend to be small, with only differences on visits for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and diabetes being statistically significant (P < .05), with cases more likely to receive appropriate care than controls (82% v 79% for COPD visits and 86% v 81% for diabetes visits). The analyses by tumor type suggest differences depending on the type of cancer. For breast and prostate cancer, cases were more likely to receive appropriate care for the same two indicators as the overall analysis. For COPD visits, 90% of breast cancer survivors versus 83% of controls and 85% of prostate cancer survivors versus 75% of controls received appropriate care. For diabetes visits, 92% of breast cancer survivors versus 84% of controls and 84% of prostate cancer survivors versus 76% of controls received appropriate care. In addition, breast cancer cases with hypercholesterolemia who were hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction were more likely than controls to have a cholesterol test every 6 months (60% v 5%), and prostate cancer survivors were less likely than controls to experience an avoidable outcome (88% v 80%). The patterns in the results for the colorectal cancer survivors are quite different. Compared with controls, survivors were less likely to receive appropriate care for five of the 10 indicators: COPD visits (75% v 83%), lipid profile within 1 year of angina diagnosis (61% v 73%), eye examinations for diabetics (42% v 49%), diabetes monitoring (26% v 31%), and not having an avoidable outcome (71% v 77%).

Table 3.

Performance on Chronic Care Quality Indicators: Overall and by Tumor Type

| Chronic Care Indicators | Overall |

Breast |

Prostate |

Colorectal |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with chronic stable angina | ||||||||

| Cases | 389/449 | 87 | 80/86 | 93 | 174/200 | 87 | 135/163 | 83 |

| Controls | 886/1,038 | 85 | 178/191 | 93 | 450/552 | 82 | 258/295 | 88 |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with congestive heart failure | ||||||||

| Cases | 884/1,031 | 86 | 193/213 | 91 | 269/309 | 87 | 422/509 | 83 |

| Controls | 1,471/1,734 | 85 | 365/415 | 88 | 662/800 | 83 | 444/519 | 86 |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||||||

| Cases | 1,054/1,281 | 82 | 236/263 | 90 | 449/528 | 85 | 369/490 | 75 |

| Controls | 1,499/1,909 | 79 | 335/406 | 83 | 721/968 | 75 | 443/535 | 83 |

| Visit every year for patients with diagnosis of transient ischemic attack | ||||||||

| Cases | 259/266 | 97 | 53/53 | 100 | 101/105 | 96 | 105/108 | 97 |

| Controls | 507/534 | 95 | 137/141 | 97 | 220/238 | 92 | 150/155 | 97 |

| Cholesterol test every 6 months for patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction and who have hypercholesterolemia | ||||||||

| Cases | — | 16 | — | 60 | — | 10 | — | 10 |

| Controls | 22/105 | 21 | — | 5 | — | 21 | 10/32 | 31 |

| Lipid profile ≤ 1 year after initial diagnosis of angina | ||||||||

| Cases | 308/449 | 69 | 58/86 | 67 | 151/200 | 76 | 99/163 | 61 |

| Controls | 755/1,038 | 73 | 143/191 | 75 | 396/552 | 72 | 216/295 | 73 |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with diabetes | ||||||||

| Cases | 1,696/1,984 | 86 | 367/398 | 92 | 817/971 | 84 | 512/615 | 83 |

| Controls | 3,037/3,769 | 81 | 645/767 | 84 | 1,461/1,919 | 76 | 931/1,083 | 86 |

| Eye examination every year for patients with diabetes | ||||||||

| Cases | 884/1,984 | 45 | 193/398 | 49 | 433/971 | 45 | 258/615 | 42 |

| Controls | 1,739/3,769 | 46 | 395/767 | 52 | 815/1,919 | 43 | 529/1,083 | 49 |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin or fructosamine every 6 months for patients with diabetes | ||||||||

| Cases | 536/1,984 | 27 | 103/398 | 26 | 271/971 | 28 | 162/615 | 26 |

| Controls | 1,070/3,769 | 28 | 223/767 | 29 | 509/1,919 | 27 | 338/1,083 | 31 |

| No avoidable outcome | ||||||||

| Cases | 2,996/3,740 | 80 | 597/751 | 79 | 1,468/1,676 | 88 | 931/1,313 | 71 |

| Controls | 5,075/6,459 | 79 | 1,086/1,402 | 77 | 2,563/3,205 | 80 | 1,426/1,852 | 77 |

NOTE. BOLD indicates statistically significantly (P < .05) better in comparison between cases and controls based on Fisher's exact test.

(—) Numerator and denominator suppressed to protect confidentiality because of small cell sizes.

Table 4 presents the results for each of the 19 acute care indicators. Although some of the denominators are small (particularly in the analyses by tumor type) and some of the indicators did not show variation, differences in the patterns of care quality emerge across cancer types. In the overall analyses, two indicators were statistically significantly different favoring the control group: ECG after initial diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF; 46% v 50%) and cholecystectomy (16% v 24%). In the prostate cancer subgroup, the control group received better care on one of these same indicators (ECG after CHF diagnosis, 44% v 52%), as well as chest radiograph after CHF diagnosis (39% v 46%). Among the colorectal cancer subgroup, there were two indicators that statistically significantly favored the control group: visits following hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction (72% v 89%) and for CHF (68% v 81%). There were no statistically significant differences in the breast cancer subgroup.

Table 4.

Performance on Acute Care Quality Indicators: Overall and by Tumor Type

| Acute Care Indicators | Overall |

Breast |

Prostate |

Colorectal |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | No. Receiving Appropriate Care/No. Eligible for Indicator | % | |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction | ||||||||

| Cases | 64/84 | 76 | 14/18 | 78 | 24/30 | 80 | 26/36 | 72 |

| Controls | 259/308 | 84 | 48/59 | 81 | 135/164 | 82 | 76/85 | 89 |

| Electrocardiogram during emergency department visit for unstable angina | ||||||||

| Cases | 20/20 | 100 | — | 100 | — | 100 | — | 100 |

| Controls | 127/127 | 100 | 32/32 | 100 | 67/67 | 100 | 28/28 | 100 |

| Follow-up visit or hospitalization ≤ 1 week after initial diagnosis of unstable angina | ||||||||

| Cases | 62/152 | 41 | 15/33 | 46 | 33/77 | 43 | 14/42 | 33 |

| Controls | 232/663 | 35 | 49/132 | 37 | 125/356 | 35 | 58/175 | 33 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with unstable angina | ||||||||

| Cases | 39/49 | 80 | — | 67 | — | 83 | — | 81 |

| Controls | 179/208 | 86 | 29/37 | 78 | 103/118 | 87 | 47/53 | 89 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure | ||||||||

| Cases | 265/352 | 75 | 76/97 | 78 | 83/99 | 84 | 106/156 | 68 |

| Controls | 795/1,006 | 79 | 172/241 | 71 | 364/447 | 81 | 259/318 | 81 |

| Electrocardiogram ≤ 3 months after initial diagnosis of congestive heart failure | ||||||||

| Cases | 469/1,025 | 46 | 122/272 | 45 | 163/369 | 44 | 184/384 | 48 |

| Controls | 1,325/2,672 | 50 | 307/643 | 48 | 639/1,230 | 52 | 379/799 | 47 |

| Chest radiograph ≤ 3 months after initial diagnosis of congestive heart failure | ||||||||

| Cases | 438/1,025 | 43 | 123/272 | 45 | 145/369 | 39 | 170/384 | 44 |

| Controls | 121/2,672 | 46 | 277/643 | 43 | 571/1,230 | 46 | 383/799 | 48 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with cerebrovascular accident | ||||||||

| Cases | 124/175 | 71 | 39/57 | 68 | 51/64 | 80 | 34/54 | 63 |

| Controls | 345/463 | 75 | 82/112 | 73 | 160/209 | 77 | 103/142 | 73 |

| Carotid imaging ≤ 2 weeks from initial diagnosis for patients hospitalized with carotid artery stroke | ||||||||

| Cases | 21/41 | 51 | — | 27 | — | 53 | — | 69 |

| Controls | 83/164 | 51 | 10/27 | 37 | 40/79 | 51 | 33/58 | 57 |

| For patients with cerebrovascular accident with eventual carotid endarterectomy, interval between carotid imaging and carotid endarterectomy < 2 months | ||||||||

| Cases | 17/20 | 85 | — | 80 | — | 90 | — | 80 |

| Controls | 63/70 | 90 | 11/12 | 92 | 31/35 | 89 | 21/23 | 91 |

| Electrocardiogram within 2 days of initial diagnosis of transient ischemic attack | ||||||||

| Cases | 121/373 | 32 | 37/106 | 35 | 56/158 | 35 | 28/109 | 26 |

| Controls | 318/965 | 33 | 88/250 | 35 | 138/442 | 31 | 92/273 | 34 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with transient ischemic attack | ||||||||

| Cases | 34/42 | 81 | — | 79 | — | 88 | — | 73 |

| Controls | 125/150 | 83 | 41/47 | 87 | 49/56 | 88 | 35/47 | 75 |

| For patients with transient ischemic attack with eventual carotid endarterectomy, interval between carotid imaging and carotid endarterectomy < 2 months | ||||||||

| Cases | — | 100 | — | 100 | — | 100 | — | 100 |

| Controls | 20/21 | 95 | — | 100 | — | 90 | — | 100 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with diabetes | ||||||||

| Cases | 333/461 | 72 | 85/116 | 73 | 136/188 | 72 | 112/157 | 71 |

| Controls | 898/1,173 | 77 | 179/233 | 77 | 462/609 | 76 | 257/331 | 78 |

| Visit ≤ 2 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with depression | ||||||||

| Cases | 82/160 | 51 | 27/50 | 54 | 27/50 | 54 | 28/60 | 47 |

| Controls | 212/362 | 59 | 49/92 | 53 | 85/140 | 61 | 78/130 | 60 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with malignant or otherwise severe hypertension | ||||||||

| Cases | 16/19 | 84 | — | 88 | — | 80 | — | 83 |

| Controls | 39/57 | 68 | 13/20 | 65 | 11/13 | 85 | 15/24 | 63 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with GI bleeding | ||||||||

| Cases | 72/98 | 74 | 17/25 | 68 | 24/30 | 80 | 31/43 | 72 |

| Controls | 149/195 | 76 | 42/62 | 68 | 60/77 | 78 | 47/56 | 84 |

| Cholecystectomy (open or laparoscopic) for patients with cholelithiasis and one or more of the following: cholecystitis, cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis | ||||||||

| Cases | 43/271 | 16 | 12/64 | 19 | 17/98 | 17 | 14/109 | 13 |

| Controls | 107/447 | 24 | 25/117 | 21 | 53/196 | 27 | 29/134 | 22 |

| Arthroplasty or internal fixation of hip during hospital stay for hip fracture | ||||||||

| Cases | 50/117 | 43 | 17/41 | 42 | 11/24 | 46 | 22/52 | 42 |

| Controls | 81/201 | 40 | 28/64 | 44 | 28/60 | 47 | 25/77 | 33 |

NOTE. BOLD indicates statistically significantly (P < .05) better in comparison between cases and controls based on Fisher's exact test.

(—) Numerator and denominator suppressed to protect confidentiality because of small cell sizes.

The results of the multivariate models combining all of the chronic and acute indicators, respectively, largely confirmed the patterns seen in the individual indicators (Fig 1). Colorectal cancer survivors were less likely than controls to receive appropriate care on both the chronic (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.95) and acute (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.85) indicators. Prostate cancer survivors were more likely to receive appropriate chronic condition care (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.38) but less likely to receive quality acute condition care (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.87). Breast cancer survivors received care equivalent to controls on both the chronic (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.17) and acute (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.13) condition indicators. All covariates except SEER region were statistically significant in the prostate cancer chronic model, but in general, the covariates were not statistically significant in the other five models. SEER region and comorbidity score were significant in the breast cancer chronic and acute models, respectively. Sex and comorbidity score were significant in the colorectal chronic model. The only statistically significant interaction we found was with case control status and comorbidity score in the prostate and breast cancer chronic models (P = .004 and .001, respectively). In the prostate cancer model, patient cases with fewer comorbidities were more likely to receive chronic care indicators than controls (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.52). For those with more comorbidities, the association was the same, though not as strong in magnitude (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.25). In the breast cancer model, the same pattern emerged. Patient cases with fewer comorbidities were more likely to receive chronic care indicators than controls (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26 to 1.52), with a lesser magnitude in those with more comorbidites (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.27).

Fig 1.

Odds ratios (squares, breast cancer; diamonds, prostate cancer; circles, colorectal cancer) and 95% CIs from models combining the chronic and acute care indicators for cases versus controls (reference group), adjusting for age (65-74, 75+ years), race (white, black, other), sex (colorectal analyses only), comorbidity score, state buy-in, urban/rural residence, and SEER region (combining Atlanta and rural Georgia, and combining all California registries).

DISCUSSION

The issue of comorbid condition care in cancer survivors has been understudied. As treatments improve and survivors live longer after a cancer diagnosis, appropriate care for comorbid conditions takes on greater importance. This study examines this important issue and benefits from several strengths: examining care quality for a range of chronic and acute comorbid conditions, including survivors of three different tumor types, comparing cancer survivors' care with that of noncancer controls, and focusing on the transition period when active cancer treatment is ending.

Thus, our findings are informative on several different levels. First, we found that patterns of care receipt depend on the type of cancer survived. Breast cancer survivors tend to do as well as controls; prostate cancer survivors do better on chronic care but worse on acute care; and colorectal cancer survivors are consistently less likely to receive recommended care than controls. Finally, focusing on day 366 through day 1,095 from diagnosis addresses a period that may be particularly important for ensuring that patients do not get “lost in transition.”

The study most similar to this one15 examined preventive and comorbid condition care quality in 5-year colorectal cancer survivors. It also found that colorectal cancer survivors were less likely to receive appropriate chronic condition care than controls, with no clear pattern in acute care quality. Other studies comparing survivors' care with that of controls have focused on preventive care. Yu et al16 found higher rates of mammography in female colorectal cancer survivors compared with controls. In prostate cancer, survivors were more likely to receive certain services and less likely to receive others.17 Studies examining preventive care in breast cancer survivors have also been mixed, with some studies finding better care on at least some measures18 and others finding worse care,19 with the eligibility criteria for the control group having important implications for the results.20,21 Thus, these prior studies also suggest differences in care quality by type of cancer survived, similar to the findings presented here.

Although the findings are informative, several limitations of our analysis warrant discussion. First, although this analysis suggests differences in comorbid condition care quality across cancer types, it does not provide evidence on why; ongoing research is exploring the factors associated with quality comorbid condition care. In addition, sample sizes were small for several indicators, particularly in the subgroup analyses, and the comparison of cancer cases and controls on 29 quality indicators both overall and by cancer type resulted in a large number of comparisons. To address both of these issues, we combined the chronic and acute care indicators, respectively, in logistic regression models and used these models in our definitive tests of differences between groups. Notably, even in the unadjusted analyses both overall and for each subgroup, the statistically significant differences were all in the same direction, either favoring the cancer survivors or favoring the controls. If the associations found were spurious, one might expect some differences to favor the cases and some to favor the controls.

There is also the possibility of misclassification bias as a result of the reliance on diagnosis and billing codes to define patients' eligibility and care receipt. For example, we required only one claim for a condition in the year following diagnosis using the same approach as Earle and Neville.15 Although this approach may be less specific, we would not expect to see differential misclassification between cancer cases and controls. Thus, we would not expect bias in our primary analyses comparing cancer survivors' care to that of controls. There are, however, some differences that may be occurring in the coding between survivors and controls. Given that we matched controls to cases 2:1, we might expect the denominators for the controls to be about double those for cases. We found higher rates of chronic conditions in our cancer survivors, which is consistent with prior research.2 For the acute indicators, the control denominators are more than double those for cases. It is possible that this results from symptoms of and hospitalizations for noncancer problems being attributed to cancer. Another difference that may occur between cancer cases and noncancer controls relates to counting visits. In general, the indicators require specific diagnosis and procedure codes to determine the nature of the visit, but given that cancer cases tend to have more visits overall than controls,17,19 cases may be more likely to meet the quality standards simply by having more visits. This would only strengthen our findings related to less care receipt in colorectal cancer.

Other limitations of this analysis relate to the nature of all analyses that use the SEER-Medicare database: the data are restricted to older adults living in the SEER regions and enrolled continuously in the fee-for-service Medicare program, and no information is available on why care was or was not provided. We used the most recent SEER-Medicare data available at the time of our study's initiation; however, newer data are now available, and future research could investigate whether the patterns found here persist.

Despite these limitations, these results have several important implications. First, in terms of survivorship research, these findings indicate that analyses combining multiple cancer types may not be appropriate. In fact, our overall analyses masked important differences in the patterns of care in the individual tumor groups. In terms of clinical implications, these results suggest that there may be certain groups (eg, colorectal cancer survivors) that are less likely to receive appropriate care. Additional research is needed to explore the patient and provider factors associated with the differences found in care quality. Further, interventions designed to improve care may need to be focused on these vulnerable groups, and evaluations of these interventions may be more likely to demonstrate benefits when implemented in cancer populations for which there is evidence of worse care quality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the efforts of those involved with the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Information Management Services; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The collection of the California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; by the National Cancer Institute SEER program under Contracts No. N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, No. N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and No. N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Program of Cancer Registries under Agreement No. U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and endorsement by the California Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended, nor should it be inferred.

Appendix

Table A1.

ICD-9 Diagnosis and CPT Billing Codes for Indicator Specifications

| Quality Measure | ICD-9 Code (and CPT code) Indicators of a Patient Case | CPT Code or ICD-9 Procedure Code for Meeting the Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic condition management | ||

| Visit every 6 months for patients with chronic stable angina | Chronic stable angina: 413.0-413.9 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058; preventive visit: 99381, 99387, 99391, 99397 |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with congestive heart failure | CHF: 428.0-428.9, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058; preventive visit: 99381, 99387, 99391, 99397 |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with COPD | COPD: 491.0-491.9, 492.0-492.8, 496 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058; preventive visit: 99381, 99387, 99391, 99397 |

| Visit every year for patients with diagnosis of transient ischemic attack | TIA: 435.0-435.9 | Office visit 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058; preventive visit: 99381, 99387, 99391, 99397 |

| Cholesterol test every 6 months for patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction and who have hypercholesterolemia | Acute MI: 410.0-410.9; anterior MI: 410.0-410.1; hypercholesterolemia: 270.0-272.2, 272.4 | Cholesterol test: 82465; multichannel tests: 80012-80019; general health panel: 80050; lipid panel: 80061; lipoprotein, HDL, VLDL, LDL cholesterol: 83715-83721 |

| Lipid profile ≤ 1 year after initial diagnosis of angina | Chronic stable angina: 413.0-413.9 | Cholesterol test: 82465; multichannel tests: 80012-80019; general health panel: 80050; lipid panel: 80061; lipoprotein, HDL, VLDL, LDL cholesterol: 83715-83721 |

| Visit every 6 months for patients with diabetes | Diabetes: 250.00-250.93 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058; preventive visit: 99381, 99387, 99391, 99397 |

| Eye examination every year for patients with diabetes | Diabetes: 250.00-250.93 | Ophthalmologic visit: 92002-92014, ICD-9 V72.0 V80.2, 95.02, 95.03, 95.05, 95.11; ophthalmoscopy: 92225-92250 |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin or fructosamine every 6 months for patients with diabetes | Diabetes: 250.00-250.93 | Hemoglobin, glycated: 83036; fructosamine: 82985 |

| Avoidable events | ||

| Among patients with known angina, ≥ three emergency department visits for cardiovascular-related diagnoses in 1 year | Chronic stable angina: 413.0-413.9 | ER visit: 99281-99285; diseases of circulatory system: ICD-9 390-459; diseases of respiratory system: ICD-9 460-519; respiratory and chest symptoms: ICD-9 786.0-786.9; vascular insufficiency, intestine: ICD-9 557.1-557.9 |

| Among patients with known cholelithiasis, diagnosis of perforated gallbladder | Cholelithiasis: 574.0-574.5 | Perforated gallbladder: ICD-9 575.4 |

| Among patients with known diabetes, admission for hyperosmolar or ketotic coma | Diabetes: 250.00-250.93 | Hyperosmolar coma: ICD-9 250.2; ketotic coma: ICD-9 250.3 |

| Among patients with known chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, subsequent admission for a respiratory diagnosis | COPD: 491.0-491.9, 492.0-492.8, 496 | Upper respiratory infection: ICD-9 465; bronchitis, acute: ICD-9 466; pneumonia: ICD-9 480-486; influenza: ICD-9 487; chronic bronchitis: ICD-9 491; emphysema: ICD-9 492; asthma: ICD-9 493; chronic airway obstruction: ICD-9 496; pulmonary congestion: ICD-9 514; dyspnea: ICD-9 786.00-786.09 |

| Among patients with known emphysema, subsequent admission for a respiratory diagnosis | Emphysema: 492.0-492.8 | Upper respiratory infection: ICD-9 465; bronchitis, acute: ICD-9 466; pneumonia: ICD-9 480-486; influenza: ICD-9 487; chronic bronchitis: ICD-9 491; emphysema: ICD-9 492; asthma: ICD-9 493; chronic airway obstruction: ICD-9 496; pulmonary congestion: ICD-9 514; dyspnea: ICD-9 786.00-786.09 |

| Among patients with pneumonia, diagnosis of lung abscess or emphysema | Pneumonia (viral: 480.0-480.9; pneumococcal: 481; other bacterial: 482.0-482.9; other specified organism: 483.0-483.8); bronchopneumonia, organism unspecified: 485; pneumonia, organism unspecified: 486; influenza with pneumonia: 487.0 | Lung abscess: ICD-9 513.0; emphysema: ICD-9 510.1, 510.9 |

| Nonelective admission for congestive heart failure | CHF: 428.0-428.9, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91 | Check IP file for any admission with first listed diagnosis of CHF |

| Acute care quality indicators | ||

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction | Acute MI: 410.0-410.9; anterior MI: 410.0-410.1 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Electrocardiogram during emergency department visit for unstable angina | Unstable angina: 411.1 | ECG, evaluation: 93000-93014, ICD 89.52, 89.53; ER visit: 99281-99285 |

| Follow-up visit or hospitalization ≤ 1 week after initial diagnosis of unstable angina | Unstable angina: 411.1 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with unstable angina | Unstable angina: 411.1 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure | CHF: 428.0-428.9, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Electrocardiogram ≤ 3 months after initial diagnosis of congestive heart failure | CHF: 428.0-428.9, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91 | ECG, evaluation: 93000-93014, ICD 89.52, 89.53 |

| Chest radiograph ≤ 3 months after initial diagnosis of congestive heart failure | CHF: 428.0-428.9, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91 | Chest x-ray: 71010-71035, ICD 87.44, 87.49 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with cerebrovascular accident | CVA: 430-434.9, 436-437.9 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| For patients hospitalized with carotid artery stroke, carotid imaging ≤ 2 weeks of initial diagnosis | Carotid territory stroke: 433.1, 433.10, 433.11 | Angiogram, carotid artery: 75650-75685, ICD 88.41; noninvasive carotid imaging: 93880-93882, 70544-70549, ICD 88.71 |

| For cerebrovascular accident patients with eventual carotid endarterectomy, interval between carotid imaging and carotid endarterectomy < 2 months | CVA: 430-434.9, 436-437.9 34001, 35301; carotid endarterectomy: ICD 38.12 | Angiogram, carotid artery: 75650-75685, ICD 88.41; noninvasive carotid imaging: 93880-93882, 70544-70549, ICD 88.71 |

| Electrocardiogram within 2 days of initial diagnosis of transient ischemic attack | TIA: 435.0-435.9 | ECG, evaluation: 93000-93014, ICD-9 89.51-89.54; ECG, rhythm: 93040-93042; ECG, monitoring: 93224-93237 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with transient ischemic attack | TIA: 435.0-435.9 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| For transient ischemic attack patients with eventual carotid endarterectomy, interval between carotid imaging and carotid endarterectomy < 2 months | TIA: 435.0-435.9; carotid endarterectomy: 34001, 35301 | MRI: 70544-70549; angiogram, carotid artery: 75650-75685; noninvasive carotid imaging: 93880-93882; other: ICD-9 88.41, 88.71 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with diabetes | Diabetes: 250.00-250.93 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Visit ≤ 2 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with depression | Depression: 296.2, 296.3, 296.90, 311 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058; psychiatric visit: 90841-90844, 90862; individual medical psychotherapy: 90855; individual psychoanalysis: 90845 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with malignant or otherwise severe hypertension | Hypertension urgency or hypertension emergency: 401.0, 402.0, 403.0, 404.0, 405.0, 405.1, 405.9, 437.2 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Visit ≤ 4 weeks after discharge for patients hospitalized with GI bleeding | GI hemorrhage: 578.0-578.9; gastroesophageal laceration hemorrhage syndrome: 530.7; esophageal hemorrhage: 530.82; gastric ulcer with hemorrhage: 531.0, .2, .4, .6; duodenal ulcer with hemorrhage: 532.0, .2, .4, .6; peptic ulcer NEC with hemorrhage: 533.0, .2, .4, .6; gastrojejunal ulcer with hemorrhage: 534.0, .2, .4, .6 | Office visit: 99201-99215; office consultation: 99241-99245; home visit: 99341-99353; ER visit: 99281-99285; nursing home visit: 99301-99337; emergency office visit: 99058 |

| Cholecystectomy (open or laparoscopic) for patients with cholelithiasis and ≥ one of the following: cholecystitis, cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis | Cholelithiasis: 574.0-574.5 | Cholecystectomy: 47601-47619, 47620, 56340, 56341, 56342, ICD 51.22, 51.23; cholecystitis: 575.0, 575.1; cholangitis: 576.1; gallstone pancreatitis: 574.0, 574.1, 574.2, 577.0 |

| Arthroplasty or internal fixation of hip during hospital stay for hip fracture | Transcervical closed: 820.00-820.09; transcervical open: 820.10-820.19; pertrochanteric closed: 820.20-820.22; pertrochanteric open: 820.30-820.32; hip, NOS closed: 820.8; hip NOS open: 820.9 | Partial or total hip replacement: 27125, 27130, 27132, 27134, 27137, 27138; hip replacement: ICD 81.51-81.53; open treatment femoral, proximal, end, neck: 27236; open treatment intertrochanteric, subtrochanteric, pertrochanteric, femoral: 27244-27245; open treatment greater trochanteric: 27248; arthroplasty: ICD 78.55 |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ER, emergency room; HDL, high density lipoprotein; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; IP, inpatient; LDL, low density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NEC, not elsewhere classifiable; NOS, not otherwise specified; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VLDL, very low density lipoprotein.

Footnotes

Supported by Award No. R01CA149616 from the National Cancer Institute.

Presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2011.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or National Institutes of Health.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Kevin D. Frick, eviti (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Claire F. Snyder, Kevin D. Frick, Craig C. Earle

Collection and assembly of data: Claire F. Snyder, Kevin D. Frick, Robert J. Herbert

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: Findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanrahan EO, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Giordano SH, et al. Overall survival and cause-specific mortality of patients with stage T1a,bN0M0 breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4952–4960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowland JH, Mariotto A, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer Survivors-United States, 2007. MMWR. 2011;60:269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, et al. Postoperative mortality in cancer patients with pre-existing diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:931–939. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, et al. Long-term, all-cause mortality in cancer patients with pre-existing diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2754–2764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peairs KS, Barone BB, Snyder CF, et al. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:40–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder CF, Stein KB, Barone BB, et al. Does pre-existing diabetes affect prostate cancer prognosis? A systematic review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010;13:58–64. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein KB, Snyder CF, Barone BB, et al. Colorectal cancer outcomes, recurrence, and complications in persons with and without diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1839–1851. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA. 2001;285:885–892. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: A population-based study. Cancer. 1998;82:2123–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patnaik JL, Byers T, Diguiseppi C, et al. The influence of comorbidities on overall survival among older women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1101–1111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712–1719. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu X, McBean M, Virnig BA. Physician visits, patient comorbidities, and mammography use among elderly colorectal cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:275–282. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Herbert RJ, et al. Preventive care in prostate cancer patients: Following diagnosis and for five-year survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0181-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy CM, Clark MA, Allsworth JE. Health maintenance and screening in breast cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Peairs KS, et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: A five-year longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:469–474. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, et al. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1447–1451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Kantsiper ME, et al. Prevention, screening, and surveillance care for breast cancer survivors compared with controls: Changes from 1998 to 2002. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1054–1061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asch SM, Sloss EM, Hogan C, et al. Measuring underuse of necessary care among elderly Medicare beneficiaries using inpatient and outpatient claims. JAMA. 2000;284:2325–2333. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute: SEER-Medicare: Brief description of the SEER-Medicare database. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/overview/brief.html.

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.