Abstract

Purpose

The prevalence of off-label anticancer drug use is not well characterized. The extent of off-label use is a policy concern because the clinical benefits of such use to patients may not outweigh costs or adverse health outcomes.

Methods

Prescribing data from IntrinsiQ Intellidose data systems, a pharmacy software provider maintaining a population-based cohort database of medical oncologists, was analyzed. Use of the most commonly prescribed anticancer drugs (“chemotherapies”) that were patent protected and administered intravenously to patients in 2010 was examined. Use was classified as “on-label” if the cancer site, stage, and therapy line met the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved indication. All other use was “off-label.” Off-label use was divided by whether it conformed to National Comprehensive Care Network (NCCN) Compendium recommendations, a basis of insurer coverage policies. IMS Health National Sales Perspectives was used to estimate national spending by use category.

Results

Ten chemotherapies met inclusion criteria. On-label use amounted to 70%, and off-label use amounted to 30%. Fourteen percent of use conformed to an NCCN-supported off-label indication, and 10% of off-label use was associated with an FDA-approved cancer site, but an NCCN-unsupported cancer stage and/or line of therapy. Total national spending on these chemotherapies amounted to $12 billion (B; $7.3B on-label, $2B off-label and NCCN supported; $2.5B off-label and NCCN unsupported).

Conclusion

Commonly used, novel chemotherapies are more often used on-label than off-label in contemporary practice. Off-label use is composed of a roughly equal mix of chemotherapy applied in clinical settings supported by the NCCN and those that are not.

INTRODUCTION

The development of new anticancer drugs (“chemotherapies”) has produced reductions in cancer mortality and morbidity in the United States.1,2 Yet many novel chemotherapies are priced high relative to the existing standard of care.3 Use of these new, high-priced chemotherapies seems to be a significant driver of prescription drug spending trends.4,5

A number of authors have questioned whether some novel, high-cost chemotherapies are being used “inappropriately” in clinical practice.6–9 The extent of inappropriate chemotherapy use is a public policy concern because of the cost and potential harms to patients from the use of toxic agents with little likelihood of clinical benefit.10–13

“On-label” uses are clinical applications of a drug conforming to indications listed in a drug's label as approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); conversely “off-label” uses are those not approved by the FDA.8,9,14–19 Specifically, on-label chemotherapy use is defined by cancer site, stage, and line of therapy.20

However, not all off-label chemotherapy use is inappropriate clinical care. One critical rationale driving off-label chemotherapy use is insurance coverage and reimbursement policies. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) is the largest insurer of cancer-related treatment.1 CMS and private insurers rely on FDA approval and authoritative compendia to determine what uses of physician-administered drugs to reimburse.9,21 Compendia include listings of off-label uses determined by expert assessments of available supportive evidence.8,10,12,13,20,21 Emerging scientific evidence of novel medical treatment is commonly incorporated into guideline development. Public reports of evidence development have been shown to influence use of innovative medical care in cancer and other clinical areas.13,22–26

The contemporaneous extent of off-label use of patent-protected chemotherapies and associated spending is unknown. A 1991 study by the US Government Accountability Office surveyed oncologists and reported that the off-label use of a selected group of chemotherapies amounted to 33% of all prescriptions.27 However, physician report is likely to bias estimates of off-label use downward and, given the pace of technological change in cancer care, these results are likely not directly relevant to contemporaneous practice.28 One recent study estimated the off-label use of rituximab, a novel patent-protected chemotherapy, among patients drawn from a large proprietary insurance database.29 Results suggest the off-label use of rituximab amounted to 47%. However, this study has limited external validity because of the study's setting. The study's internal validity is also problematic because cancer site alone was used to classify on-label use without regard to stage and/or line of therapy.

We conducted a study to quantify the magnitude of on-label and off-label use of the most commonly used, patent-protected chemotherapies in a population-based sample of office-based oncology practices in 2010. The rationale for our focus on patent-protected chemotherapies was chosen to reflect policy interest in these therapies because of their high price and uncertain clinical risks when applied in the off-label setting.8,27 The novelty of the analysis over previously published work resides in the national coverage of the data set and the inclusion of cancer indication, stage, and line of therapy in classifying the use of chemotherapies. In addition, we categorized off-label use into that conforming to contemporaneous recommendations supporting insurance coverage by one CMS-approved compendium.

METHODS

The analysis uses Intellidose data (IntrinsiQ, Burlington, MA) to examine aggregate use of chemotherapies launched into the US market between 2004 and 2009 among patients with specific cancer diagnoses.28,30 The data are collected via the Intellidose software system. During the study period, Intellidose was used as the exclusive method of infused outpatient chemotherapy order entry and administrative billing for 122 medical oncology practices comprising 570 oncologists across 35 US states, 19,500 patients, 47,000 office visits, and 135,000 chemotherapy administrations. The majority of centers using the chemotherapy order entry system were nonacademic or university hospital affiliated private practices and community hospitals, clinics, and outpatient cancer care facilities. For each new patient, practice sites entered date of birth, sex, cancer type, date of diagnosis, and American Joint Committee on Cancer stage. The date of chemotherapy initiation was also recorded. Chemotherapy orders and patient data were monitored by IntrinsiQ staff oncology nurses to ensure consistency and accuracy. The system updates patients' cancer stage and line of therapy on a monthly basis. Sales validations were performed both by IntrinsiQ and through comparisons with firm-reported sales in the IMS Health National Sales Perspectives.

The sample universe was obtained by analyzing IntrinsiQ data for all administrations of chemotherapies by brand and chemical name in 2010. Chemotherapies were linked to FDA approval dates and indications from the Drugs@FDA database and cross-referenced with the MICROMEDEX DRUGDEX Evaluations database.31 The sample was restricted to those drugs available only in patent-protected formulation and those administered to patients via infusion or injection (ie, physician administered), because IntrinsiQ internal audits suggested the data quality of oral chemotherapies may be low.20,21 2010 year-end reports to shareholders for the listed manufacturer of each chemotherapy were reviewed to ascertain whether the manufacturing company maintained market exclusivity to sell the chemotherapy, the expected date of market exclusivity loss for each chemotherapy and firm, and worldwide and national sales of each chemotherapy overall and by disease category.

The unit of analysis is annual chemotherapy administrations (aggregated over calendar months). Each administration was classified as on-label if it was consistent with an FDA-approved cancer diagnosis, stage of diagnosis and line of therapy in the IntrinsiQ data set; all other use was considered off-label.14–19 To classify on-label use, the reported indication (cancer diagnosis, stage of diagnosis, line of therapy) for each chemotherapy administration was compared with the FDA-approved label (Data Supplement).24–26,32 In practice, identifying reported on-label use conforming to these standards was complicated and required significant complementary expertise given the level of detail found in the IntrinisiQ claims data (basic) relative to that specified by the FDA-approved label (highly specific). Discrepancies in assessing on-label use between reviewers were resolved by consensus among all coauthors, with final determination provided by the oncologists (V.M.V., R.L.S.).

The order entry system of Intellidose required prospective identification of clinical trial protocols, but did not distinguish between treatment and control regimens. Therefore, all chemotherapy uses associated with a clinical trial were excluded from analysis.

Estimates of the annual prevalence of on-label use of chemotherapies overall and by chemotherapy are reported. To calculate the annual prevalence of on-label prescribing, the number of annual administrations applied on-label was divided by the number of administrations for all clinical rationales. Standard deviations (SDs) for annual estimates were estimated and are reported based on monthly estimates.

Off-label uses were also stratified according to whether or not the use was supported by the December 2010 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Drugs & Biologics Compendium (NCCN).22,24,26,32 The NCCN was chosen because it is one of several compendia approved by Congress to guide CMS coverage and reimbursement policy9,21 and because of the coauthors' familiarity with the methodology of NCCN assessments (V.M.V., R.L.S., P.B.B.). Three authors (R.M.C., A.C.B., and V.M.V.) with assistance from coauthors independently reviewed the list of chemotherapy-indication pairs and matched them to NCCN recommendations. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus among all coauthors, with final determination provided by the oncologists (V.M.V., R.L.S.).

Off-label uses for each chemotherapy were also stratified by those not conforming to the NCCN but consistent with FDA-approved cancer site (Data Supplement). A similar review and matching method to the on-label and off-label supported by NCCN recommendations was employed.

2010 annual sales for each chemotherapy were obtained from IMS Health National Sales Perspectives (NSP). NSP is a projected audit that describes 100% of the national sales in every major class of trade and distribution channel for prescription pharmaceuticals, nonprescription products, and select self-administered diagnostic products, measuring both unit volume and invoice dollars. The NSP sample is derived from more than 1.5 billion annual transactions from more than 100 pharmaceutical manufacturers and more than 700 distribution centers. In 2010, NSP tracked sales of 5,859 nonfederal hospitals, 131,491 clinics, 59,202 retail pharmacies, 391 mail-service pharmacies, 4,842 home health facilities, and 2,840 long-term care outlets, in addition to thousands of other entities. NSP has been recently used to examine national trends in the sales of selected anticancer drugs.27

On-label spending on each chemotherapy and overall chemotherapies was calculated by multiplying total national sales derived from the NSP by the estimated percentage of on-label use derived from IntrinsiQ. However, rituximab has FDA-approved uses outside oncology not captured by IntrinsiQ data. Therefore, 2010 shareholder reports for Roche Biopharmaceuticals (parent company of Genentech) were reviewed. The report estimated that 16% of rituximab sales were for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune disorders.33 Consequently, 16% of total national sales of rituximab were subtracted from NSP sales. Off-label spending on chemotherapies and off-label spending on chemotherapies supported by NCCN recommendations by chemotherapy and overall chemotherapy were calculated in an analogous manner.

To check the robustness of estimates to choice of year, the prevalence of on-label use among study chemotherapies in 2009 was estimated. The University of Chicago institutional review board approved the study.

RESULTS

Among the 30 most commonly used chemotherapies, 20 chemotherapies were excluded because their patent expired before the first quarter of 2010 or because the chemotherapy was an oral formulation. Although gemcitabine lost patent protection in late December 2010, it was included in the sample.

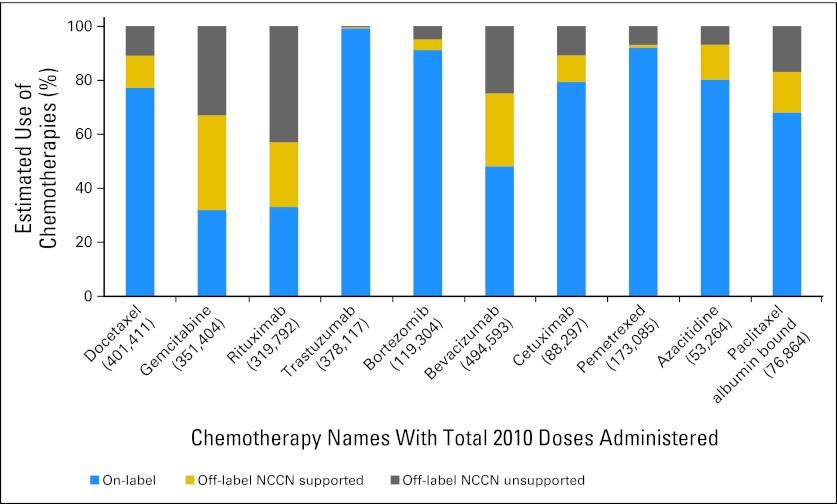

Figure 1 reports the names of each chemotherapy and the estimated percentage of on-label use of each chemotherapy in 2010, displayed in order of initial market launch date. On-label estimates range from a low of 32% for gemcitabine (SD = .01), 33% for rituximab (SD = .02), and 48% for bevacizumab (SD = .01) to a high of 92% for bortezomib (SD = .04) and pemetrexed (SD = .01) and 99% for trastuzumab (SD = .01). Overall, chemotherapy on-label use amounted to 70% (SD = .04) and off-label use amounted to 30% (SD = .03).

Fig 1.

Estimated use of chemotherapies on-label, off-label (National Comprehensive Cancer Network Drugs & Biologics Compendium [NCCN] supported), and off-label (NCCN unsupported).

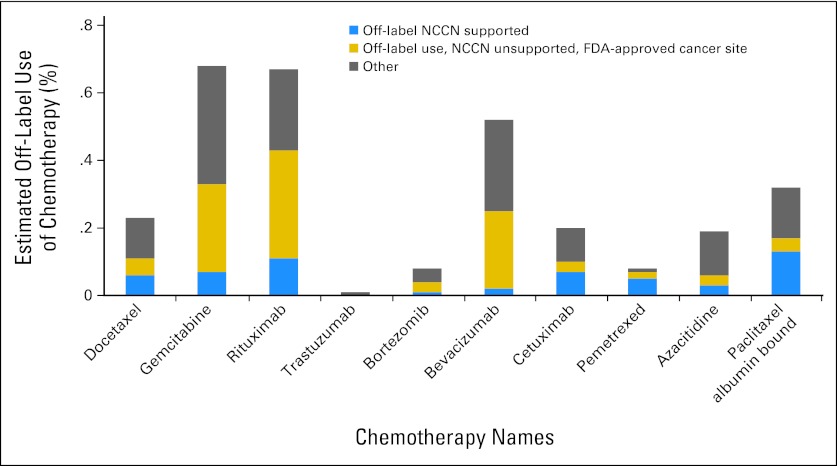

Figure 2 reports the estimated percentage of off-label use of each chemotherapy in 2010, stratified by whether the use conformed to NCCN recommendations. We further classified off-label use by whether it was consistent with FDA-approved cancer site. Off-label use supported by NCCN recommendations varies considerably by chemotherapy, ranging from less than 10% for trastuzumab (SD = .001) and pemetrexed (SD = .003) to more than 50% for azacitidine (SD = .02), docetaxel (SD = .01), bevacizumab (SD = .02), and gemcitabine (SD = .01). Variation is also observed between chemotherapies in use not supported by NCCN but consistent with FDA-approved cancer site. Overall, 14% (SD = .02) of chemotherapy use was associated with an NCCN-supported indication, and 10% (SD = .01) of use was associated with an FDA-approved cancer site, but an unapproved and NCCN unsupported cancer stage and/or line of therapy.

Fig 2.

Estimated off-label use of chemotherapies: off-label National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Drugs & Biologics Compendium supported, off-label NCCN unsupported, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved cancer site, and other.

Table 1 reports IMS Health NSP sales data for the 10 chemotherapies examined in the study. National sales of these 10 chemotherapies totaled close to $12 billion (B) in 2010. Overall, on-label sales amounted to $7.3B, and off-label sales amounted to $4.5B. Spending on off-label use conforming to NCCN recommendations amounted to $2B; $2.5B was for off-label uses not consistent with NCCN recommendations. Off-label use of bevacizumab was the single largest contributor to sales of off-label chemotherapies; gemcitabine and rituximab were estimated to have off-label sales larger than on- label sales.

Table 1.

2010 US Spending on Sample Chemotherapies for Cancer Treatment by On-Label and Off-Label Uses

| Chemotherapy | US Manufacturer | Market Launch Date | Total US Sales* ($M) | Estimated US Sales |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Label† ($M) | Off-Label ($M) | Off-Label, NCCN Supported ($M) | Off-Label, Other | ||||

| Docetaxel | sanofi-aventis US | May 1996 | 1,198 | 928 | 271 | 144 | 127 |

| Gemcitabine | Lilly | May 1996 | 780 | 250 | 530 | 273 | 257 |

| Rituximab | Genentech | Nov 1997 | 2,320 | 922 | 1,398 | 557 | 998 |

| Trastuzumab | Genentech | Sep 1998 | 1,538 | 1,523 | 15 | 15 | 0 |

| Bortezomib | Millennium Pharma/Takeda | May 2003 | 580 | 534 | 46 | 23 | 25 |

| Bevacizumab | Genentech | Feb 2004 | 3,100 | 1,158 | 1,942 | 837 | 768 |

| Cetuximab | ImClone/Lilly | Feb 2004 | 709 | 567 | 142 | 70.9 | 69 |

| Pemetrexed | Lilly | Feb 2004 | 992 | 913 | 79 | 10 | 68 |

| Azacitidine | Celgene | May 2004 | 292 | 237 | 55 | 38 | 18 |

| Paclitaxel albumin bound | Abraxis Bioscience/Celgene | Jan 2005 | 345 | 224 | 121 | 52 | 59 |

| Total annual revenue | 11,951 | 7,255 | 4,479 | 2,020 | 2,390 | ||

Total US Sales were provided by IMS Health National Sales Perspectives. Only sales of the drug for cancer treatment are reported. According the 2010 Genentech/Roche Annual Report to shareholders, rituximab total US Sales included 16% for the treatment of noncancer diagnoses. Noncancer sales for rituximab were excluded from those reported in the table.

Sales by on-label category were calculated for each drug by multiplying the percentage of use by on-label and off-label use estimated by total cancer-related annual sales.

Results were similar in 2009; On-label use amounted to 68% in 2009 (SD = .04; t test with unequal variances assumed, P = .97).

DISCUSSION

We aimed to quantify the magnitude of on-label and off-label use of commonly used, patent-protected, infused chemotherapies among a population-based cohort of oncologists in the United States in 2010. On-label use in our sample amounted to 70% (SD = .04); off-label use amounted to 30% (SD = .03). Fourteen percent of use was off-label but supported by NCCN recommendations. Ten percent of use was unsupported by the NCCN, but consistent with FDA-pproved cancer site. 2010 spending on these chemotherapies amounted to $12B; spending on off-label use amounted to $4.5B. Sensitivity analyses suggest the results are robust to year choice.

The results have several important implications. First, infused chemotherapies are used on-label more often than previous oncology-specific estimates suggest.12,20–23 Our estimates of the off-label use of rituximab (33%) are less than that reported by Van Allen et al (47%).24 This difference may be related to that study's focus on the application of rituximab in noncancer settings and reliance on the use of diagnosis codes alone to assess on-label rituximab use in cancer applications.34 The results suggest that these chemotherapies are used off-label with a frequency similar to that of other commonly used medication classes in the nononcology setting (20% to 50%).14–19

Second, a sizable proportion of off-label use seems to be concentrated in clinical applications supported by the NCCN. Compendia are of significant value to clinicians because they provide evidence in support of treatments' use in patient populations too small for trial recruitment and for patients who would not meet strictly defined patient and/or tumor inclusion criteria in randomized clinical trials (including disease progression).28,30–32 However, compendia do not require firms to provide the same amount and quality of evidence as required by the FDA. Recent reports suggest such recommendations may be subject to reporting delays and the expert consultants critical to the inclusion and exclusion practices of the NCCN may have significant financial conflicts of interest.35,36 Furthermore, caution should be used in interpreting these estimates as evidence of “appropriate use” in 2010. We could not distinguish between uses supported by the NCCN at a level 2a recommendation versus 2b or 3 recommendation. Level 2b and 3 recommendations may not be considered by many physicians, nor payers, to be clinically appropriate.

Third, the use of administrative data to examine the prevalence of off-label chemotherapy use has limitations. Multiple challenges were encountered in matching the relatively basic level of detail found in a prescribing pattern audit of medical oncologists to the highly specific standards conforming to the FDA label and NCCN recommendations. Although the data employed contained fairly detailed information on cancer site, stage, and therapy line, we were unable to examine patient correlates of off-label use, including age and the presence of comorbid conditions. We were also unable to examine other aspects of on-label use, including concurrent chemotherapy use, duration of chemotherapy use, and chemotherapy dose indicated in the clinical application of some chemotherapies examined (Data Supplement). The presence and results of somatic and germ-line genotyping tests indicated in the clinical application of some chemotherapies examined (cetuximab, rituximab, and trastuzumab) were also unavailable in the data (Data Supplement). Therefore, data limitations dictated that we attribute on-label and NCCN-consistent uses to those conforming to cancer site, stage, and line alone. These omissions likely bias the estimates of on-label use upward, yet the magnitude of the bias is unknown.

Some of these limitations could be overcome by using detailed data linking treatment use to individual patient level data. However, medical record abstraction entails considerable administrative costs, consequently limiting the sample size of a potential study. Future research examining the quality of chemotherapy use could employ administrative data and physician surveys37 to prioritize chemotherapies or chemotherapy classes and, secondarily, medical record abstraction to address these limitations. It is likely that medical record abstraction efforts would be most valuable targeted to assessing the use of chemotherapies with significant clinical outcome uncertainty, safety concerns, and/or vulnerable patient subpopulations.38

The analyses have other limitations. It is possible that provider selection into the IntrinsiQ sampling frame could bias the estimates toward capturing patterns of use from more technologically savvy practices. It is possible these practices may be more “guideline adherent” for quality of care purposes and/or to maximize insurer reimbursement recovery. This would bias on-label use estimates upward. The sampling frame is based on commonly used, patent-protected chemotherapies; we cannot determine whether the relative proportion of on-label to off-label use is similar to that of less commonly used chemotherapies and those that have undergone patent expiration and generic entry. IMS Health's NSP data were used to ascertain national spending by chemotherapy; although sales validations performed by IntrinsiQ provided some assurance of the external validity of our spending estimates, we are not aware of any independent assessments of volume or sales comparability between the two data sets. Finally, it is possible some off-label use not supported by NCCN recommendations in 2010 is related to public reports of emerging scientific evidence in the United States and abroad. Although it is outside the scope of the current analysis, understanding the responsivity of chemotherapy use to such reports is an important area for future research.

In sum, the analyses provide empirical evidence that commonly used, high-cost, patent-protected infused chemotherapies are used on-label frequently. Sample chemotherapies are used off-label with a frequency similar to that of other commonly used patent-protected prescription drugs in the nononcology setting. 2010 spending on these chemotherapies amounted to approximately $12B; spending on on-label use amounted to $7.3B and off-label use amounted to more than $4.5B. Off-label use is composed of a roughly equal mix of chemotherapy applied in clinical settings supported by the NCCN and those that are not.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Tina Shih, PhD, John Cunningham, MD, PhD, and members of the Sections of Hematology/Oncology and Pediatric Hematology/Oncology at the University of Chicago Biologic Sciences Division for helpful comments and suggestions; no compensation was paid to them for their efforts.

Footnotes

See accompanying editorial on page 1125; listen to the podcast by Dr Hershman at www.jco.org/podcasts

The efforts of R.M.C. and A.C.B. were funded by Grant No. K07 CA138906 award to R.M.C. from the National Cancer Institute.

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from IntrinsiQ. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not those of IntrinsiQ or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from IMS Health.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Arielle C. Bernstein, Makovsky (C); Richard L. Schilsky, Universal Oncology (U) Consultant or Advisory Role: Richard L. Schilsky, Foundation Medicine (C) Stock Ownership: Richard L. Schilsky, Universal Oncology, Foundation Medicine Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: Meredith B. Rosenthal, Economic expert for plaintiffs in suit against the maker of rituximab (Rituxan). (C) Other Remuneration: Peter B. Bach, Genentech

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rena M. Conti, Peter B. Bach

Financial support: Rena M. Conti

Administrative support: Rena M. Conti

Collection and assembly of data: Rena M. Conti, Arielle C. Bernstein

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1407–1427. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MEDPAC: Report to Congress: Variation and innovation in Medicare. 2006. http://www.medpac.gov/publications/congressional_reports/June03_Ch9.pdf.

- 3.Schrag D. The price tag on progress: Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:317–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the UnitedStates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aitken ML, Berndt ER, Cutler DM. Prescription drug spending trends in the US: Looking beyond the turning point. Health Affairs. 2009;28:151–160. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer RJ. Targeted therapy for advanced colorectal cancer: More is not always better. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:623–625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0809343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadler E, Eckert B, Neumann PJ. Do oncologists believe new cancer drugs offer good value? Oncologist. 2006;11:90–95. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bach PB. Limits on Medicare's ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:626–633. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0807774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: How can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:626–634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrank WH, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of pharmacologic care for adults in the United States. Med Care. 2006;44:936–945. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223460.60033.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality: Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA. 1998;280:1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laetz T, Silberman G. Reimbursement policies constrain the practice of oncology. JAMA. 1991;266:2996–2999. [Erratum: 267: 3287, 1992] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giordano SH, Lin YL, Kuo YF, et al. Decline in the use of anthracyclines for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2232–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021–1026. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1280–1285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goulding MR. Inappropriate medication prescribing for elderly ambulatory care patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:305–312. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sebalt RJ, Petrie A, Goldsmith CH, Marenette MA. Appropriateness of NSAID and Coxib prescribing for patients with osteoarthritis by primary care physicians in Ontario: Results from the CANOAR study. Am J Manage Care. 2005;10:742–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naunton M, Peterson GM, Bleasel MD. Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:333–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conti RM, Busch AB, Cutler DM. The appropriate use of antidepressants in 2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:703. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.7.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levêque D. Off-label use of anticancer drugs. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Society of Clinical Oncology: Reimbursement for cancer treatment: Coverage of off-label drug indications. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3206–3208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith BD, Pan IW, Shih YC, et al. Adoption of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for breast cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:798–809. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay P. Do pharmaceutical sales respond to scientific evidence? J Econ Manage Str. 2002;11:551–594. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azzoli CG, Temin S, Aliff T, et al. 2011 focused update of 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3825–3831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, et al. Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:466–472. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman JM, Li E, Doloresco F, et al. Projecting future drug expenditures: 2012. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:405–421. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States General Accounting Office: Off-Label Drugs: Reimbursement Policies Constrain Physicians in Their Choice of Cancer Therapies. 1991. Sep, GAO/PEMD-91-14. http://archive.gao.gov/d18t9/144933.pdf. [PubMed]

- 28.Conti RM, Bernstein A, Meltzer DO. How do initial signals of quality influence the diffusion of new medical products? The case of new cancer treatments. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2012;23:123–148. doi: 10.1108/s0731-2199(2012)0000023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Allen EM, Miyake T, Gunn N, et al. Off-label use of rituximab in a multipayer insurance system. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:76–79. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrams TA, Brightly R, Mao J, et al. Patterns of adjuvant chemotherapy use in a population-based cohort of patients with resected stage II or stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3255–3262. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DRUGDEX System: CD-ROM, version 5.1. Thomson Micromedex [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recent developments in Medicare coverage of off-label cancer therapies. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:18–20. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0913001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roche: Basel, Switzerland: F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd; 2010. 2010 Annual Report. www.roche.com/gb10e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walton SM, Schumock GT, Lee KV, et al. Prioritizing future research on off-label prescribing: Results of a quantitative evaluation. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:1443–1452. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.12.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinney R, Abernethy AP, Matchar DB, et al. White paper: Potential conflict of interest in the production of drug compendia, project ID: CMPE 1207. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Technology Assessment Report,; April 2009; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abernethy AP, Hammond JM, Hubbard ML, Patwardham MB, et al. Compendia for coverage of off-label uses of drugs and biologics in an anticancer chemotherapeutic regimen. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Technology Assessment Report,; May 2007; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peppercorn J, Burstein H, Miller FG, et al. Self-reported practices and attitudes of US oncologists regarding off-protocol therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5994–6000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The patient-centered outcomes research institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307:1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.