Abstract

Alterations in oscillatory brain activity are strongly correlated with cognitive performance in various physiological rhythms, especially the theta and gamma rhythms. In this study, we investigated the coupling relationship of neural activities between thalamus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) by measuring the phase interactions between theta and gamma oscillations in a depression model of rats. The phase synchronization analysis showed that the phase locking at theta rhythm was weakened in depression. Furthermore, theta-gamma phase locking at n:m (1:6) ratio was found between thalamus and mPFC, while it was diminished in depression state. In addition, the analysis of coupling direction based on phase dynamics showed that the unidirectional influence from thalamus to mPFC was diminished in depression state only in theta rhythm, while it was partly recovered after the memantine treatment in a depression model of rats. The results suggest that the effects of depression on cognitive deficits are modulated via profound alterations in phase information transformation of theta rhythm and theta-gamma phase coupling.

Keywords: Neural phase–phase coupling, Cognitive deficit, Local field potential, Theta rhythm, Gamma rhythm, Depression

Introduction

The cerebral cortex generates multitudes of oscillations at different frequencies. Various physiological rhythms strongly innervate memory and cognitive performances by the alteration of brain oscillations activity. Especially in the local field potentials (LFPs), theta oscillations (4–8 Hz) reflect the encoding of new information, while gamma frequency oscillations (30–80 Hz) have been suggested to underlie various cognitive and motor functions (Csicsvari et al. 2003). Indeed, the neural oscillations modulate the memory and cognitive functions by means of phase synchronization which is a fundamental neural mechanism, and neural coupling between different brain regions (Fell and Axmacher 2011).

Cognitive deficits in cerebral cortex have been proved to be a significant impairment of function, which is a core symptom of major depression. Also, the thalamo-cortico-thalamic circuits may partly underlie the cognitive dysfunction from neuropsychiatric disorders (Dalley et al. 2004; Bruno and Sakmann 2006). These findings were in line with our previous studies in animal models of schizophrenia and depression (Quan et al. 2010, 2011b). Importantly, our previous results showed that the strength and directionality of phase coupling between thalamus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) were significantly decreased in depressed rats, which was associated with the alteration of synaptic plasticity in thalamo-cortical (TC) pathway (Zheng et al. 2011).

Consequently, we wonder whether the cognitive deficits induced by depression are able to be characterized in the rhythm alterations, especially in the phase–phase coupling between these rhythms. In the present study, we examined the phase–phase coupling on theta and gamma rhythms, and estimated directionality of neural information flow (NIF) using the algorithm based on phase dynamics, in order to reveal how the brain oscillations changed activity and interacted with each other, associated with the cognitive deficiency in depression.

Methods

Animals and electrophysiological experiment

The chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) was used as an animal model of depression in the study. The rats were randomly divided into three groups: control group (Con, n = 6), stressed group (Str, n = 6) and stressed + memantine treated (MEM, n = 6) groups. It is well known that as an NMDA receptor antagonist, memantine manifests tolerated and beneficial effects of cognitive measures (Reisberg et al. 2003; Tariot et al. 2004). Both Str and MEM groups were performed by CUS procedure for 21 days (Willner 1997). Several stressors were applied in apparently random order and at changeable times, with each stressor performed once a week. And then the rats of Str and MEM groups received daily i.p. injections of saline solution (NaCl 0.9 %) and memantine hydrochloride (20.0 mg/kg,) respectively. Spontaneous LFPs at both thalamic nucleus, viz. laterodorsal thalamic nucleus dorsomedial part (LDDM) [AP—2.3–2.8; L 1.4–2.0; H 4.2–4.7] and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [AP 3.0–3.3; L 0.7–1.0; H 2.8–3.4] areas in control, stressed and stressed + memantine treated groups, were recorded under 30 % urethane anesthesia on the stereotaxic apparatus (4 ml/kg, i.p., Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The LFP signals were sampled simultaneously, which lasted for almost 5 min for each rat. They were fed into a multi-channel differential amplifier and simultaneously recorded with a sampling rate of 200 Hz. The experimental details can be seen in our previous reports (Quan et al. 2010, 2011b).

Algorithms for phase–phase coupling

LFP signals were filtered at delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–15 Hz), beta (15–30 Hz) and slow gamma (30–40 Hz) frequency bands, using FIR band filter with hamming window (filter order = 512). Phase series were extracted by means of Hilbert transform from filtered LFP signals.

The phase synchronization analysis can be quantitated by means of phase locking values (PLV) at five frequency bands for the three groups (Rosenblum et al. 1996). The PLV is defined as

|

Also the radial distance (r) values of n: m phase–phase locking can be measured for theta-gamma phase coupling. The phase difference is generalized as

|

which is calculated for different n:m ratios, e.g., 1:1, 1:2, …, 1:10, etc. A Larger value of r refers to a more unimodal distribution of  , i.e. stronger phase coupling (Rayleigh test for uniformity) (Tass et al. 1998; Belluscio et al. 2012).

, i.e. stronger phase coupling (Rayleigh test for uniformity) (Tass et al. 1998; Belluscio et al. 2012).

In addition, the algorithm of evolution map approach (EMA) (Rosenblum and Pikovsky 2001; Smirnov and Andrzejak 2005) was employed to measure the directional influences between the thalamus and mPFC over different narrow frequency bands. Given two systems X1 and X2, the phase dynamics can be established as

|

and the parameters in f1,2 can be fitted by aligned Fourier series  . Here

. Here  are phase variables, so that the functions

are phase variables, so that the functions  ,

,  are

are  -periodic in all arguments. Small parameters

-periodic in all arguments. Small parameters  characterize the strength of the coupling and

characterize the strength of the coupling and  are random terms. The unidirectional influences between the systems are quantified by the coefficients

are random terms. The unidirectional influences between the systems are quantified by the coefficients  as

as

|

And then their coupling direction can be calculated and the direction index denoted as

|

The index  is an integrated measure of how strong each system is driven and of how sensitive it is to the drive. The coefficient

is an integrated measure of how strong each system is driven and of how sensitive it is to the drive. The coefficient  and

and  refer to the forward and backward unidirectional influences, i.e.

refer to the forward and backward unidirectional influences, i.e.  and

and  , respectively in the present study.

, respectively in the present study.

Data and statistical analysis

Multivariate statistical test was applied in order to compare the phase coupling indices in all the frequency bands among three groups. Post hoc statistics were made using the LSD test (Fisher’s least significant difference t test) for multiple comparisons. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 software and the significant level was set at 0.05.

Result

Power spectra

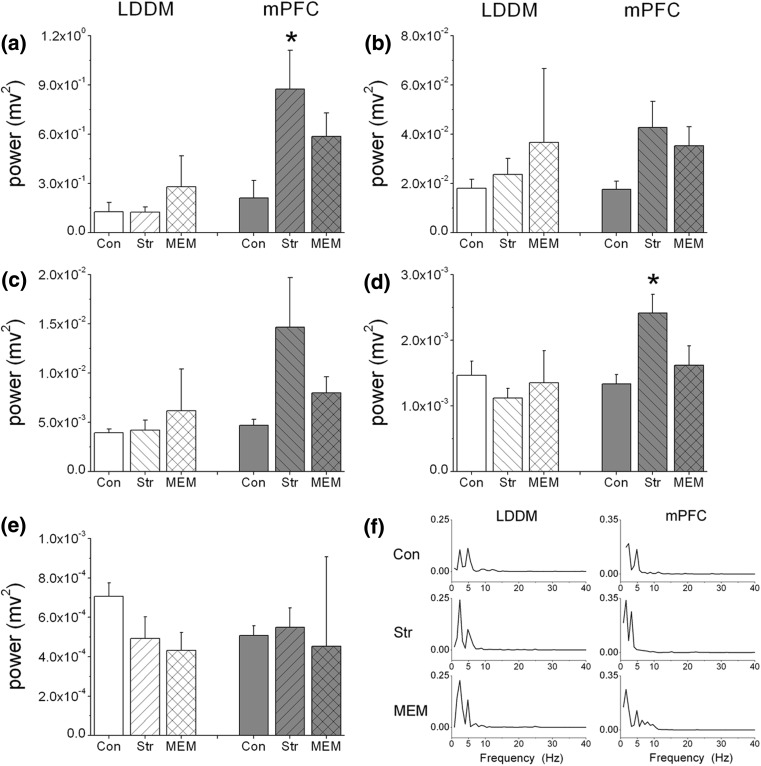

The intragroup averages of spectral power density computed for the LFPs at LDDM and mPFC are illustrated in Fig. 1. The statistical tests showed that it is only the mPFC region, in which the power spectrum were significantly changed at the delta (p = 0.030, Fig. 1a) and beta (p = 0.014, Fig. 1d) frequency bands among these three groups. In the multiple comparisons, the power spectrum were considerably increased at the delta (p = 0.028, Fig. 1a) and beta (p = 0.016, Fig. 1d) in Str group compare to that in Con group. However, it was found that mematine treatment had little effect for stressed rats on the power density at both LDDM and mPFC areas, with an increased tendency of low frequency power and a decreased tendency of high frequency power between Str and MEM groups (Fig. 1a–e). Figure 1f shows the examples of power spectra in one normal rat (Con, in upper panel), one stressed rat (Str, middle panel) and one stressed + memantine treated rat (MEM, lower panel) at LDDM and mPFC regions.

Fig. 1.

Mean power spectra of local field potentials from 1 to 40 Hz across five frequency bands and the spectra of several representative signals in thalamus and prefrontal cortex among Con, Str and MEM groups. a–e Comparison of LFP power spectra at delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–15 Hz), beta (15–30 Hz) and slow gamma (30–40 Hz) frequency bands among these three groups (n = 6). Powers of thalamus (left) and mPFC (right) were showed respectively. Error bars indicate SEM, *p < 0.05 for comparisons among these three groups in mPFC. f Examples of power spectra in one normal rat (Con, in upper panel), one stressed rat (Str, middle panel) and one stressed + memantine treated rat (MEM, lower panel) at both LDDM and mPFC regions. Y-axis refers to the absolute power spectrum and the unit is mv2

Phase synchronization

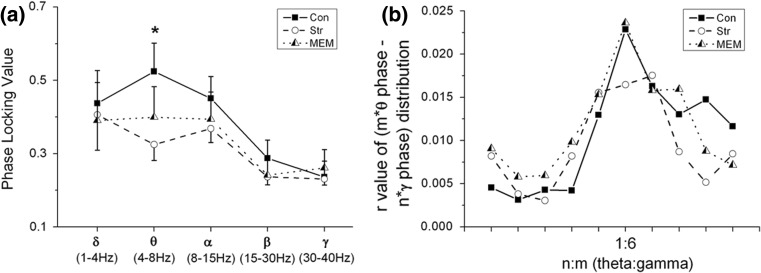

The phase synchronization analysis at five frequency bands for these three groups is shown in Fig. 2a. From the small phase locking values (PLV, almost <0.5), it demonstrated that weak phase synchronization was exhibited between LDDM and mPFC in all the three groups. In addition, one-way ANOVA analysis showed that there were no significant differences of synchronization indices PLV among the three groups at theta frequency band (p = 0.121). However, it was found that PLV value was significantly decreased in Str group (p = 0.045, by the post hoc LSD test) compared to that in Con group. After memantine treatment, PLV value was slightly increased in MEM group compared to that in Str group.

Fig. 2.

Phase synchronization index. a Phase locking value (PLV) of LFPs between LD thalamus and mPFC at five frequency bands for Con, Str and MEM groups (n = 6). *p < 0.05 for comparisons between the Con group and the Str group. b Phase–phase (n: m) coupling between theta and gamma oscillations. Mean radial distance values (r values) from the distribution of the difference between m*theta and n*gamma phases calculated for different ratios among three groups

n:m phase–phase coupling

In order to explore the cross frequency theta-gamma phase coupling quantitatively, we measured the radial distance values (r) of circular distribution from the difference between m*theta phase and n*gamma phase for ten ratios (Fig. 2b) (Tass et al. 1998). A discrete peaks at n:m = 1:6 ratio was yielded weakly, corresponding to possible 6 gamma cycles within a theta period, determined by Rayleigh test for uniformity (p < 0.05). Interestingly, such a phase–phase coupling between theta-gamma rhythms was diminished in depression state, and come back to the normal in the MEM group, although there was no statistical differences by one-way ANOVA analysis (p = 0.407).

Analysis of coupling direction

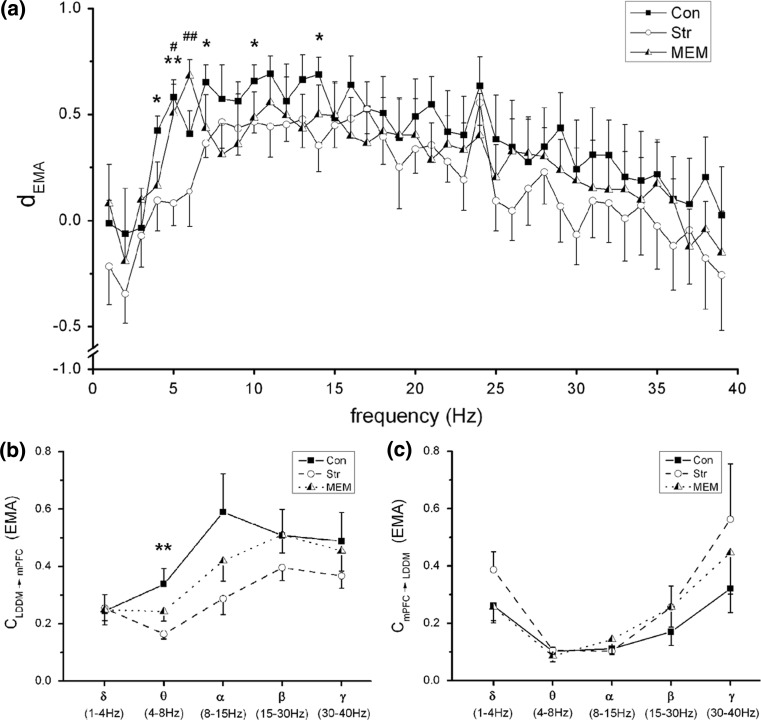

Furthermore, we measured the driver-response relationship of phase–phase coupling at all the frequency bands, in order to determine the direction of NIF in the TC pathway. Phase series were extracted by Hilbert transform on narrow frequency bands, which were filtered over 1–40 Hz with 1 Hz bandwidth (FIR band filter with hamming window, filter order = 512) from original LFP signals. Coupling directional indices d, obtained by means of EMA algorithm in the Con, Str and MEM groups, are showed in Fig. 3a. It can be seen that there was bidirectional information flow between LDDM and mPFC areas since the  value fluctuated in [−1, 1]. In general, directional indices

value fluctuated in [−1, 1]. In general, directional indices  over all the rhythms exhibited the reduced tendency in the Str group compared to that in the Con group, while it was partially enhanced by memantine treatment (p < 0.001).

over all the rhythms exhibited the reduced tendency in the Str group compared to that in the Con group, while it was partially enhanced by memantine treatment (p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

The coupling direction index  and c. a

and c. a varied with frequency from 1 to 40 Hz (n = 6) from LDDM to mPFC. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 between Con and Str groups and #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 between Str and MEM groups. The unidirectional phase–phase coupling indices between LDDM and mPFC: b

varied with frequency from 1 to 40 Hz (n = 6) from LDDM to mPFC. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 between Con and Str groups and #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 between Str and MEM groups. The unidirectional phase–phase coupling indices between LDDM and mPFC: b (forward) and c

(forward) and c (backward) at five rhyrhms. **p < 0.01 between Con and Str groups

(backward) at five rhyrhms. **p < 0.01 between Con and Str groups

Especially for the theta rhythm, the directional index of phase information flow was significantly diminished with the cognition dysfunction in depression state, and nearly back to normal after treatment. In addition, the results of the unidirectional indices  and

and  at theta rhythm further supported this point of view, showing that the forward

at theta rhythm further supported this point of view, showing that the forward  altered as the same way as

altered as the same way as  among three groups (p = 0.011). The post hoc comparisons detected the significant difference between Con and Str groups (p = 0.003), which was showed in Fig. 3b. However, the backward

among three groups (p = 0.011). The post hoc comparisons detected the significant difference between Con and Str groups (p = 0.003), which was showed in Fig. 3b. However, the backward  at theta rhythm had no statistical differences (Fig. 3c).

at theta rhythm had no statistical differences (Fig. 3c).

Discussion

In our previous studies, the Morris water maze experiment showed that the rats in depression performed worse in reversal learning related stages (Quan et al. 2011b). Also the synaptic plasticity on TC pathway was impaired in an animal model of depression by inducing long term potentiation (LTP) (Quan et al. 2011a; Zheng et al. 2011). Both of the findings indicated there were learning and memory deficits in the depression model of rats. Our findings of alteration in power spectra are in good agreement with the results of recent studies on bipolar disorder patients (Özerdem et al. 2008; Başar and Güntekin 2008), in which the absolute power spectra of LFP at mPFC region were increased in stressed rats compared to that of normal ones, over delta and beta frequency bands. After memantine treatment the mPFC power spectrum was decreased, but it did not recover to its normal level. Several previous studies reported that cortical slow oscillations were shown to contribute to memory consolidation, and these observations might related to the fatigue mechanism inhibiting the neurons activity (Mattia and Sanchez-Vives 2011; Weigenand et al. 2012).

Synchronous oscillations in different frequency bands are considered as an important mechanism linking single-neuron activity to behavior and mental disorders (Başar-Eroglu et al. 1992; Gallinat et al. 2006). Interestingly, the considerable reduction of theta rhythm synchronization in the Str group was detected, in line with the findings in Schizophrenia and Alzheimer subjects (Yener et al. 2007; Ford et al. 2008). In addition, the analysis of cross frequency phase coupling showed that the n:m (1:6) theta-gamma rhythm coding was involved in cognitive function, although the value r appeared smaller than that in CA1 of hippocampus (Belluscio et al. 2012), mainly because of the weak coupling between LDDM and mPFC. These results suggested that the phase synchronization of both theta and gamma rhythms in TC pathway was implicated in the information coding associated with learning and memory. In addition, the analysis of coupling direction suggested that the oscillations in thalamus nuclear predominantly drove those in mPFC, which was in line with the synaptic transformation through TC pathway. Importantly, functional impairment associated with depression might result from the decreased information transmission at theta rhythm in the thalamo-cortico-thalamic circuits. Interestingly, it was also found in a rat model of vascular dementia, in which the alterations of coupling direction were associated with cognitive deficits and synaptic plasticity impairment (Xu et al. 2012).

A growing body of researches suggests that brain glutamate systems may be involved in the pathophysiology of depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressants, besides the monoamine neurotransmitters. In our previous study especially, the level of NR2B subunit of NMDA receptor was reduced in PFC in depression, and memantine treatment showed that antidepressant effects were related to its up-regulation of NR2B expression (Quan et al. 2011a). In addition, theta activity was considered to mediate neuronal coupling between the cortex and the hippocampus via glutamatergic neurotransmission (Başar and Güntekin 2008). As a result, the alteration in glutamate system, including the NMDA receptors, might be the most significant factor of reduced synchronization and coupling on theta rhythm in depression. With respect to the antidepressant effect of memantine, there is one hypothesis that AMPA receptor activation is required for antidepressant effect. They are possibly on GABA-releasing interneuron, in which GABA release is blocked when antagonized. Consequently, the alteration of GABA releasing, mediated by the NMDA receptors, might be implicated in the theta-gamma synchronization in depression.

Taken together, our findings suggest that cognitive deficits in depression, such as learning and memory dysfunction, are implicated in the alteration of phase–phase coupling strength in theta and gamma oscillators. Furthermore, the modifications of various brain rhythms and their interaction might be involved in regulating the behavioral functions. However, investigating the relationship between phase–phase coupling strength in theta and gamma oscillators and cognitive deficits is still at an early stage of development. It remains an open issue as to whether there are other oscillatory frequency bands involved which may indicate an alteration of cognitive functions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171053, 11232005) and Tianjin research program of application foundation and advanced technology (12JCZDJC22300).

References

- Başar E, Güntekin B. A review of brain oscillations in cognitive disorders and the role of neurotransmitters. Brain Res. 2008;1235:172–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başar-Eroglu C, Başar E, Demiralp T, et al. P300-response: possible psychophysiological correlates in delta and theta frequency channels. A review. Int J Psychophysiol. 1992;13:161–179. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(92)90055-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluscio MA, Mizuseki K, Schmidt R, et al. Cross-frequency phase–phase coupling between theta and gamma oscillations in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2012;32:423–435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4122-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno RM, Sakmann B. Cortex is driven by weak but synchronously active thalamocortical synapses. Science. 2006;312:1622–1627. doi: 10.1126/science.1124593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J, Jamieson B, Wise KD, et al. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron. 2003;37:311–322. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW. Prefrontal executive and cognitive functions in rodents: neural and neurochemical substrates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, Axmacher N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:105–118. doi: 10.1038/nrn2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM, Roach BJ, Hoffman RS, et al. The dependence of P300 amplitude on gamma synchrony breaks down in schizophrenia. Brain Res. 2008;1235:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallinat J, Kunz D, Senkowski D, et al. Hippocampal glutamate concentration predicts cerebral theta oscillations during cognitive processing. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattia M, Sanchez-Vives MV. Exploring the spectrum of dynamical regimes and timescales in spontaneous cortical activity. Cogn Neurodyn. 2011;6:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s11571-011-9179-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özerdem A, Güntekin B, Tunca Z et al (2008) Brain oscillatory responses in patients with bipolar disorder manic episode before and after valproate treatment. Brain Res 1235:98–108 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Quan MN, Tian YT, Xu KH, et al. Post weaning social isolation influences spatial cognition, prefrontal cortical synaptic plasticity and hippocampal potassium ion channels in Wistar rats. Neuroscience. 2010;169:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan MN, Zhang N, Wang YY, et al. Possible antidepressant effects and mechanisms of memantine in behaviors and synaptic plasticity of a depression rat model. Neuroscience. 2011;182:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan MN, Zheng CG, Zhang N, et al. Impairments of behavior, information flow between thalamus and cortex, and prefrontal cortical synaptic plasticity in an animal model of depression. Brain Res Bull. 2011;85:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, et al. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1333–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum MG, Pikovsky AS. Detecting direction of coupling in interacting oscillators. Phys Rev E. 2001;64:45202. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.045202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum MG, Pikovsky AS, Kurths J. Phase synchronization of chaotic oscillators. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;76:1804–1807. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov DA, Andrzejak RG. Detection of weak directional coupling: phase-dynamics approach versus state-space approach. Phys Rev E. 2005;71:36207. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.036207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, et al. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:317–324. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tass P, Rosenblum MG, Weule J, et al. Detection of n:m phase locking from noisy data: application to magnetoencephalography. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;81:3291–3294. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.3291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigenand A, Martinetz T, Claussen JC. The phase response of the cortical slow oscillation. Cogn Neurodyn. 2012;6:367–375. doi: 10.1007/s11571-012-9207-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134:319–329. doi: 10.1007/s002130050456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Li Z, Yang Z et al (2012) Decrease of synaptic plasticity associated with alteration of information flow in a rat model of vascular dementia. Neuroscience 206:136–143 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yener G, Güntekin B, Öniz A, et al. Increased frontal phase-locking of event-related theta oscillations in Alzheimer patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors. Int J Psychophysiol. 2007;64:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Quan M, Yang Z, et al. Directionality index of neural information flow as a measure of synaptic plasticity in chronic unpredictable stress rats. Neurosci Lett. 2011;490:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]