Abstract

Palliative care is cited as providing improved communication, symptom control, treatment knowledge, and survival. The authors feel primary palliative care skills should be part of a physician's armamentarium.

As palliative care specialists in oncology, we are used to the questions: Why palliative care? Shouldn't the palliative care types be doing the palliative care? As Abrahm points out, most oncologists think they already do palliative care,1 although when measured, their performance needs significant improvement.2

We have some good answers for these questions now. As defined by the Center to Advance Palliative Care,2a palliative care is “specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses, focused on providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress—whatever the diagnosis,” with an explicit goal to “improve quality of life for both the patient and the family. Palliative care is provided by a team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work with a patient's other doctors to provide an extra layer of support, and can be provided together with curative treatment.”

Palliative care concurrent with usual oncology care is now endorsed by ASCO because it results in better quality of life, better quality of care, improved symptom management, and equal or better survival, at an affordable cost.3 The enhanced survival of patients who receive palliative care4,5 or hospice care6,7 is an unexpected benefit. For years we have heard, “Hospice will just give them morphine to make them comfortable and they'll die sooner.” But the data suggest otherwise.

There are three types of palliative care.8 Primary palliative care is delivered every day in the oncology office. Secondary palliative care is delivered by specialized teams at specific programs or inpatient units. And tertiary palliative care is delivered by specialized teams with expertise in advanced pain and symptom management, such as implantable drug delivery systems, palliative sedation, or advanced delirium management. In this article, we show what we have done in our oncology office that has effectively integrated palliative care into the treatment of patients with incurable cancer.

How to Do Palliative Care in the Office

Table 1 shows a list of components that must be in place for successful palliative care. As the table shows, much of our new learning is about communication.9,10

Table 1.

Components of Office-Based Primary Oncology Palliative Care

|

Abbreviation: QOPI, Quality Oncology Practice Initiative.

Ask, Tell, Ask (and ask again)

In the Temel et al study of patients with lung cancer, longer survival was linked to a better understanding of the incurable nature of the disease, and those who understood their disease received less intravenous chemotherapy in the last 60 days of life.11 The improved survival of the concurrent care group makes sense given the 2% and 0% response rate for third- and fourth-line chemotherapy in patients whose lung cancer has progressed on a platinum and a taxane drug12,13 (but with preserved possibly fatal adverse effects). The palliative care team met with the patients every 3 or 4 weeks to discuss symptoms, disease understanding, and coping.

This is not a one-time conversation. Nearly all oncologists tell patients when they have an incurable illness, but then most of the remaining conversation is about chemotherapy, and the coping part is neglected.14 This has to be a repeating conversation,15 and there are some excellent triggers: when the disease grows, when the prognosis changes, when the performance status declines. In these cases, when the patient may be on second- or third-line chemotherapy, there are some important questions that should be asked: “Do you have a will? Do you have a living will? What does it say about CPR? Who do you want to make medical decisions, if you can't? Have you discussed this with her or him? Are there spiritual issues? Are there family issues? Have you met with hospice yet? [3-6 months before death] Have you thought about where you would like to be for your death? Let's start with you doing a life review; what you want people to remember about you. Oncologists need a script for this conversation as much as one for adjuvant chemotherapy. These are learnable skills, as shown by results of programs such as Oncotalk, a program designed to teach oncologists better communication skills, including challenging topics such as recurrence of cancer and code status discussions. After participation, providers made significantly more use of the skills needed to discuss end-of-life issues, deliver bad news, and discuss transitions in care goals.16

Always Do a Symptom Assessment

It likely does not matter which symptom assessment scale is used, and we like a simple one17 as shown in Table 2. The key is to remind ourselves to ask about more than just pain, since most patients with cancer have multiple symptoms—if we notice. Some areas that we have learned to focus on include delirium in the hospital,18,19 and depression in the outpatient setting. For outpatients, the simple question “Are you depressed?” has excellent reliability, especially if we prompt them with “yes, no, or possibly” as possible answers.20 For inpatients, small daily doses of haloperidol (1 to 3 mg) help delirium,21 but only if it is diagnosed. We have learned from our nursing colleagues to do the relatively simple Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit for monitoring delirium22,23 assessment. Issues involved in getting the symptom assessments into the electronic medical record and acted on are beyond the scope of this review, but should be no different than for performance status.

Table 2.

The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Condensed Rounding Tool

| MSAS-C: 0 = none, 1 = a little bit, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a lot, 4 = very much, 7 = refused | ||||||||||

| Reported by: Patient/Caregiver/RN/MD | ||||||||||

| Unable to respond: Yes No | ||||||||||

| Delirious: Yes No [N.B. Use haloperidol or Seroquel (Quetiapine), NOT BENZODIAZEPINE.] | ||||||||||

| Pain | Tiredness | Nausea | Depression | Anxiety | Drowsiness | Anorexia | Constipation | Dyspnea | Secretions | |

| 0 | ||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||

Abbreviation: MSAS-C, Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Condensed.

Do a Spiritual Assessment

Our patients want us to be aware of their spirituality, even if they do not expect us to engage in it. One of the key parts of palliative care is to involve spiritual care specialists such as chaplains for patients facing challenging existential adjustments. There is accumulating evidence that programs that do spiritual assessments and have active chaplaincy programs have better patient satisfaction24 and fewer in-hospital deaths.25,26 In fact, if spiritual care is provided by the medical team, rather than by community services, patients with terminal illness are five time more likely to use hospice and have better quality-of-life scores.27 We use the Faith, Importance, Community, Address (FICA) tool,28 the FICA Spiritual History Tool,28a or simply ask, “Is religion or spirituality important to you?” Have established links to chaplains available if the person responds, “Yes…I have neglected that part of my life.”

Make a Hospice Information Referral When the Patient Still Has 3 to 6 Months to Live

This is one of the key practical points of the ASCO Provisional Clinical Opinion, and it is endorsed by the ASCO University Top Five choices in oncology practice.29 Oncologists who say they cannot predict the future course of patients have excellent tools to help improve their prognostic forecasting, which most patients want. It is relatively easy to predict which patients have less than 6 months to live30: decline in performance status, weight loss/anorexia, any malignant effusion, or hypercalcemia should all trigger discussion about hospice. It is especially important to have a frank discussion about prognosis when the time is short, and there are excellent prognostic scales well validated in cancer patients.30a The use of scales is critical because the closer oncologists are to the patient, the more they tend to overestimate survival. Oncologists have been found to overestimate survival by a factor of 5.3.31

The advantages to this hospice information visit are several. First, it brings hospice into the picture as part of best practices if and when it is needed (and hospice has been endorsed by ASCO for at least 15 years32) Second, it tells the patient and the family that there will indeed be care for them when it is needed, rather than just being told “there is nothing more we can do.” Third, it reinforces that the patient has an illness that will lead to the need for hospice and eventual death, which will help that patient and their family start planning for the future. It moves the anguish of facing a terminal illness way upstream, when patients and families are not in extremis, and makes eventual transitions easier. Finally, it allows the hospice team to get to know the patient and family before an imminent death and crisis. In US Oncology practices that adopted hospice information referrals as part of their clinical pathways project, patients with lung cancer spent more than a month in hospice have better patient (Roy Beveridge, MD, and J. Russell Hovermann, MD, PhD, personal communication, November 2012). This is compared to the 0 to 4 hospice days in the usual oncologic care arm of Temel's trial (without palliative care intervention). An earlier study of concurrent care with upstream referral and the opportunity for patients to meet the hospice care team showed that hospice length of stay increased from 14 to 48 days.33

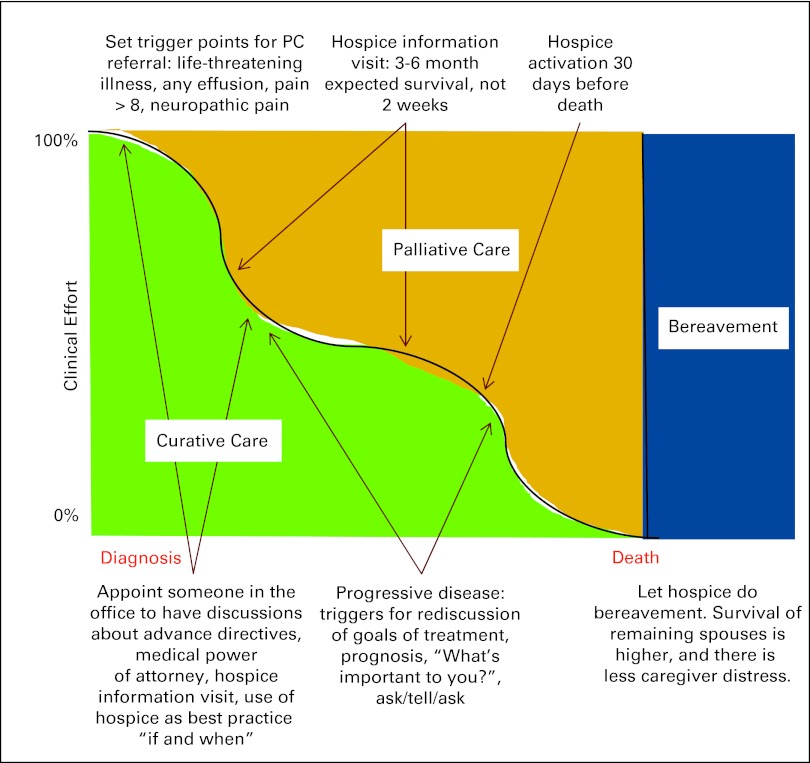

Figure 1.

Diagram showing palliative care (PC) moved upstream.

Audit Hospice Referrals

ASCO's Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) shows us what we do, not what we think we do. The average patient with cancer lives just 8 days in hospice nationwide,34 and 20% of patients at Johns Hopkins Oncology live less than a week. Nationwide, only 2% of patients with hematologic malignancy ever use hospice. The way to change this is to have the hospice information visit, make the referral as soon as chemotherapy stops working, and audit our performance. Blayney showed that the use of chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks before death could be decreased from 50% to 20% in a month through QOPI audit and provision of feedback.35 Hospices can also give feedback to physicians on our performance, but they may hesitate for fear of losing referrals.

Set Up Best Practices for Seriously Ill Patients Who Have Less Than a Year to Live

Nearly all of our practices have standard antiemetic orders, doses calculated from a spreadsheet, the available lines of chemotherapy, and so on. We can do the same standardization with integration of palliative care: build in the automatic referrals to hospice with second-line chemotherapy for solid tumors, malignant effusions/ascites/hypercalcemia, or decline in ECOG performance status to 2. Well-designed clinical pathways are not a panacea,36 but they appear to improve care and reduce cost in patients with colon37 and lung38 cancer.

Take Advantage of Decision Aids

Decision aids can be used to provide accurate prognosis to those patients who want to know their prognosis. Most oncologists use Adjuvant!,which gives exact prognoses and improves decision making.39 There are excellent decision aids for non–small-cell lung cancer on the ASCO Cancer.Net Web site that show the benefits of first-, second-, third-, and fourth-line chemotherapy.40 Most important, they provide a set of transition prompts that allow clinicians to move from simply telling patients “there is nothing more I can do” to actively engaging them in taking ownership of their end-of-life process.

Use Palliative Care “Pearls”

To alleviate disease- or treatment-related symptoms, use metoclopramide, haloperidol, or olanzapine for cancer-related nausea41; ginger 0.5-1.0 g/d for nausea42; American ginseng to improve fatigue,43 and dexamethasone for both intestinal obstruction and to improve fatigue and quality of life.44 Octreotide, long used for malignant bowel obstruction,45 is not superior to placebo when dexamethasone and ranitidine are used for intestinal obstruction,46 at a cost saving of $25-$100 a day. If your patient has an uncomplicated nonvertebral symptomatic bone metastasis, the American Society of Radiation Therapeutic Oncology recommends a single large fraction of radiation rather than 10; ask your radiation therapist to do this as the default practice.47 Make sure patients get into hospice within the last 30 days of life, to allow discussions that reduce caregiver distress,48 as hospice increases the chance of survival of the remaining spouse.49 These are some things we do as palliative care doctors that work, are incredibly simple, and usually inexpensive.

Yes, We Can Do This

Alesi documented several examples of practices that have fully integrated palliative care into oncology practice.50 This improved symptom management and actual symptoms, mostly paid for itself, and was doable in typical cancer offices. Whether integrated (the same practitioners doing palliative and oncology care) or consultative (referral to specialists in or out of the practice) models are better cannot be answered at the present time.

Conclusions

Palliative care is increasingly cited as providing better communication, symptom control, and knowledge about treatment options and goals; not hastening death; and improving survival. ASCO recommends concurrent palliative care early in the cancer disease course for any patient with advanced cancer or high symptom burden. Primary palliative care skills should be part of any physician's armamentarium. Like any other clinical skills, they can be learned, and will improve with use and practice. These skills include ensuring accurate and multidirectional communication by using techniques such as ask, tell, ask; performing symptom and spiritual assessments; recognizing triggers for palliative care and hospice referrals; and using evidence-based decision aids for prognostication. For patients with likely less than 6 months to live, normalizing hospice services through routine hospice information referrals can calm the often turbulent transitions from primarily disease-focused to symptom-focused management.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Thomas J. Smith

Financial support: Thomas J. Smith

Administrative support: Thomas J. Smith

Collection and assembly of data: Lauren M. King, Thomas J. Smith

Data analysis and interpretation: Thomas J. Smith

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Abrahm JL. Integrating palliative care into comprehensive cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1192–1198. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blayney DW, Severson J, Martin CJ, et al. Michigan oncology practices showed varying adherence rates to practice guidelines, but quality interventions improved care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:718–728. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Center to Advance Palliative Care. What is palliative care? http://www.getpalliativecare.org/whatis/

- 3.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, et al. Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, et al. Hospice care and survival among elderly patients with lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:929–939. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schapira L. Communication: What do patients want and need? J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:249–253. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0856501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Back AA, Tulsky JR. Mastering Communication With Seriously Ill Patients. NewYork: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic nonsmall-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massarelli E, Andre F, Liu DD, et al. A retrospective analysis of the outcome of patients who have received two prior chemotherapy regimens including platinum and docetaxel for recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;39:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zietemann V, Duell T. Every-day clinical practice in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith TJ, Longo DL. Talking with patients about dying. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1651–1652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1211160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Kasimis B, et al. Shorter symptom assessment instruments: The Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (CMSAS) Cancer Invest. 2004;22:526–536. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200026487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291:1753. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: Validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skoogh J, Ylitalo N, Larsson Omeróv P, et al. ‘A no means no’–measuring depression using a single-item question versus Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1905–1909. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui D, Bush SH, Gallo LE, et al. Dose in the management of delirium in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: Validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1370. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomasi CD, Grandi C, Salluh J, et al. Comparison of CAM-ICU and ICDSC for the detection of delirium in critically ill patients focusing on relevant clinical outcomes. J Crit Care. 2012;27:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams JA, Meltzer D, Arora V, et al. Attention to inpatients' religious and spiritual concerns: Predictors and association with patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1265–1271. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1781-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flannelly KJ, Emanuel LL, Handzo GF, et al. A national study of chaplaincy services and end-of-life outcomes. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Nawawi NM, Balboni MJ, Balboni TA. Palliative care and spiritual care: The crucial role of spiritual care in the care of patients with advanced illness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:269–274. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283530d13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: Associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM. Evaluation of the FICA Tool for Spiritual Assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health. FICA Spiritual History Tool. http://www.gwumc.edu/gwish/clinical/fica-spiritual/fica-spiritual-history/index.cfm.

- 29.ASCO University. Five things physicians & patients should questions. ( http://university.asco.org/five-things-physicians-patients-should-question-capture)

- 30.Salpeter SR, Malter DS, Luo EJ, et al. Systematic review of cancer presentations with a median survival of six months or less. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:175–185. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Wilner LS, Arnold R. The Palliative Performance Scale. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_125.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith TJ, Schnipper LJ. The American Society of Clinical Oncology program to improve end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 1998;1:221–230. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1998.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitorak EF, Armour M, Sivec HD. Project Safe Conduct integrates palliative goals into comprehensive cancer care: An interview with Elizabeth Ford Pitorak and Meri Armour. Innov End-of-Life Care. 2002;4(4) doi: 10.1089/109662103768253812. www.edc.org/lastacts] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:786–796. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blayney DW, McNiff K, Hanauer D, et al. Implementation of the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative at a university comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3802–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of integrated care pathways: What works, for whom, in which circumstances? Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2009;7:61–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2009.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoverman JR, Cartwright TH, Patt DA, et al. Pathways, outcomes, and costs in colon cancer: Retrospective evaluations in two distinct databases. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(suppl 3):52s–59s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neubauer MA, Hoverman JR, Kolodziej M, et al. Cost effectiveness of evidence-based treatment guidelines for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer in the community setting. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:12–18. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siminoff LA, Gordon NH, Silverman P, et al. A decision aid to assist in adjuvant therapy choices for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:1001–1013. doi: 10.1002/pon.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Decision Aid Set: Stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer. http://www.asco.org/ASCO/Downloads/Cancer%20Policy%20and%20Clinical%20Affairs/Clinical%20Affairs%20(derivative%20products)/NSCLC/NSCLC%20ALL%20Decision%20Aids%2011.12.09.pdf.

- 41.Gupta M, Davis M, Legrand S, et al. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer—“The Cleveland Clinic Protocol.”. J Support Oncol. pii doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.10.002. S1544-6794(12)00173-5. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: A URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1479–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barton DL, Soori GS, Bauer BA, et al. Pilot study of Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng) to improve cancer-related fatigue: A randomized, double-blind, dose-finding evaluation: NCCTG trial N03CA. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0642-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yennurajalingam S, Frisbee-Hume S, Delgado-Guay MO, et al. Dexamethasone (DM) for cancer-related fatigue: A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled tiral. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:567s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.4661. (suppl; abstract 9002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercadante S, Porzio G. Octreotide for malignant bowel obstruction: Twenty years after. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;83:388–392. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson K. Octreotide pricey and no better in cancer bowel obstruction. Medscape Medical News. 2012. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/772544.

- 47.Expert Panel On Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases. Lutz ST, Lo SS, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria non-spine bone metastases. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:521–526. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: A matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:465–475. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alesi ER, Fletcher D, Muir C, et al. Palliative care and oncology partnerships in real practice. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:1287–1290. 1292–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]