Increased provider and professional society participation should form the basis of ongoing and future REMS standardization discussions with the FDA to work toward overall improvement of risk communication.

Abstract

To address oncology community stakeholder concerns regarding implementation of the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program, ASCO sponsored a workshop to gather REMS experiences from representatives of professional societies, patient organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Stakeholder presentations and topical panel discussions addressed REMS program development, implementation processes, and practice experiences, as well as oncology drug safety processes. A draft REMS decision tool prepared by the ASCO REMS Steering Committee was presented for group discussion with facilitated, goal-oriented feedback.

The workshop identified several unintended consequences resulting from current oncology REMS: (1) the release of personal health information to drug sponsors as a condition for gaining access to a needed drug; (2) risk information that is not tailored—and therefore not accessible—to all literacy levels; (3) exclusive focus on drug risk, thereby affecting patient-provider treatment discussion; (4) REMS elements that do not consider existing, widely practiced oncology safety standards, professional training, and experience; and (5) administrative burdens that divert the health care team from direct patient care activities and, in some cases, could limit patient access to important therapies.

Increased provider and professional society participation should form the basis of ongoing and future REMS standardization discussions with the FDA to work toward overall improvement of risk communication.

Introduction

The implementation of Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) has been controversial since the program began. Although designed to minimize risks of potentially dangerous therapies, complex REMS programs for certain oncology drugs fail to consider education and training of oncology professionals and safety practices already embedded in clinical settings. REMS programs have also resulted in significant administrative requirements and unintended consequences. These include disclosure of patient information to drug manufacturers, inappropriate redundancy in chemotherapy safety procedures, and administrative burdens that may limit patient access and increase cost without enhancing patient safety.

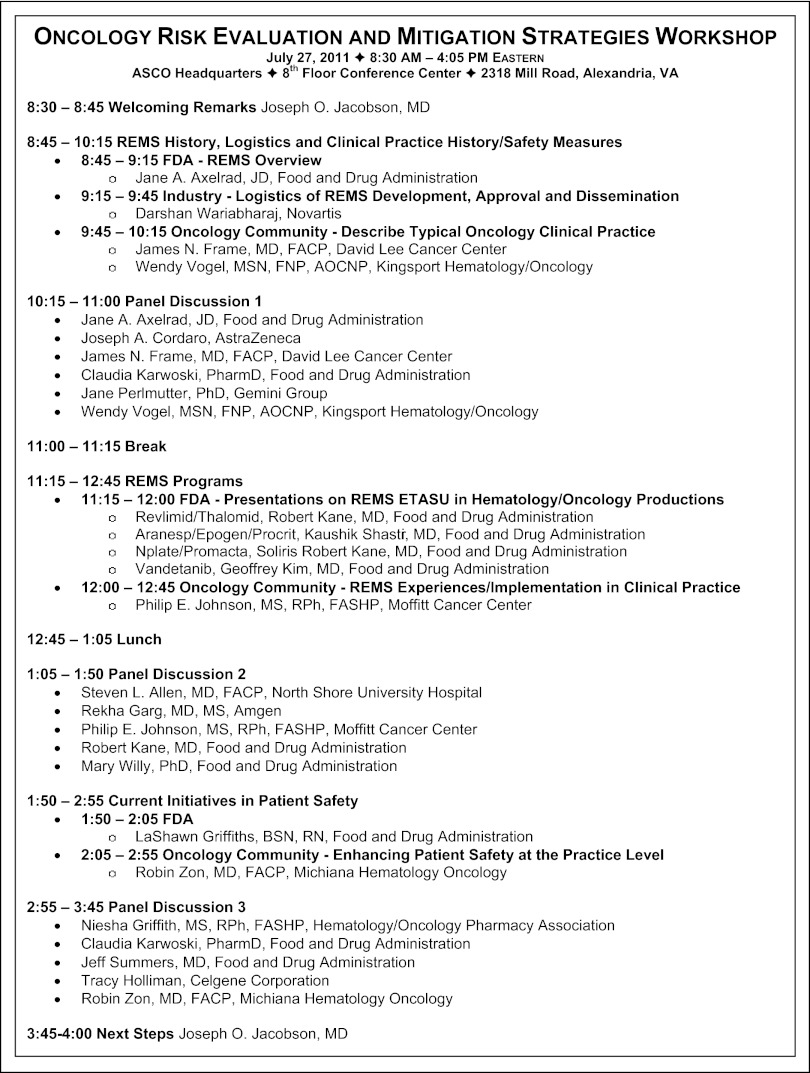

ASCO convened a workshop on July 27, 2011 to hear from all oncology stakeholders affected by REMS and to discuss possible alternative approaches for the management of drug risks (Appendix Figure A1, online only). This article reviews the background of the REMS program, its components and processes, and describes oncology health care providers' and industry experiences and perspectives on REMS implementation. Workshop proposals for a path forward in conjunction with recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) programmatic changes are presented.

History of REMS at the FDA

The FDA first began using drug safety strategies similar to REMS in 1992, with regulations allowing for accelerated approval and restrictions for safe use of marketed drugs.1 The intent was to facilitate approval when promising treatments for life-threatening diseases carried a risk-benefit balance that might otherwise prevent approval. This history has been previously reviewed.2

The REMS program, which expands the FDA's risk management authority, originates from the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA).3,4 FDAAA arose from a perceived need to protect public health, especially in the wake of high-profile drug recalls, such as rofecoxib (Vioxx).5 The most publicized risk-related issues occurred when drugs were not used to treat life-threatening conditions. The REMS program was designed to “ensure that drugs that could not otherwise be approved because the risks without a REMS would outweigh the benefits, are available to patients.”6(p56202) Oncology and hematology therapeutics typically do not fall into this category. In the treatment of cancer, drugs that demonstrate efficacy are generally approved; the risks are managed by providers who specialize in cancer treatment and associated supportive care.

The FDA's authority to require and enforce REMS extends only to the product's manufacturer; the FDA does not directly regulate health care professionals, the health care system, or patients. As a result, implementation of the most restrictive REMS elements functionally inserts manufacturers into the patient-provider relationship for drug acquisition and safety monitoring. Some REMS programs include a requirement for patients and providers to disclose confidential medical information to gain access to a marketed drug. REMS requirements, negotiated by the FDA and the manufacturer, have the potential to interfere inappropriately with patient-provider relationships, decision making, and balanced discussions of risk and benefit.

An REMS program may be proposed by either the drug manufacturer or the FDA during review of the drug application or, with approved drugs, when a new risk is identified. Once a proposal is made, the FDA determines whether an REMS program is necessary and which components are appropriate to mitigate identified risks. REMS programs are supposed to provide information about risk and constructively influence clinical decision making.

REMS Components and Process

The range of REMS components differs but includes various combinations of four possible elements, in addition to a timetable for submission of REMS program assessments (Table 1). The timetable is the only element required by law to be included in every REMS.9

Table 1.

New REMS Approved Between March 25, 2008 and October 1, 2011, Categorized by REMS Elements

| REMS Elements (in addition to a timetable for submission of assessment of the REMS) | Description of the Elements (as defined by statutory language in FDAAA) | No.7 |

|---|---|---|

| Medication Guide (MG) |

|

124* |

| Communication Plan (CP), which can be used alone or with an MG | Such plan may include

|

40 |

| Elements to assure safe use (ETASU), which can be used alone or with a CP and/or MG | ETASU shall include one or more goals to mitigate a specific serious risk, and may require that

|

21 |

| Implementation system (with ETASU only) | The element to ensure safe use may include a system through which the applicant is able to take reasonable steps to

|

† |

| Total new REMS approved | 185 |

Abbreviations: FDAAA, US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Since October 1, 2011, changes have been made to these REMS programs.8

This number was not provided in the presentation.

The law mentions a number of factors that the FDA shall consider in determining whether an REMS program is needed for a drug.10 These include:

Estimated size of the population likely to use the drug

Seriousness of the disease or condition the drug is used to treat

Expected benefit of the drug with respect to the disease or condition

Expected or actual duration of the treatment

Seriousness of the known or potential adverse events associated with the drug and the background incidence of such events in the population likely to use the drug

Whether the drug is a new molecular entity (NME)

From the date of REMS initiation (March 25, 2008) through October 1, 2011, the FDA has approved REMS for approximately 185 drugs (Table 1). Of these, 124 have a medication guide as the only component; 61 have additional components (Table 1). The FDA removed the requirements for many medication-guide-only REMS during the summer of 2011. As of October 2011, approximately 21 drugs included elements to assure safe use (ETASUs); 15 of these drugs are used in the care of patients with cancer and hematologic disorders. ETASUs can include restricted distribution plans, provider-pharmacy education certification, provider-pharmacy-patient registries, patient monitoring and/or safe use documentation (Appendix Tables A1 and A2, online only). FDAAA requires the FDA to ensure that ETASU elements are commensurate with the severity of risk and directs that such elements not be so burdensome as to impede patient access to the medication, nor unduly increase burden to the health care system.

REMS program assessments are intended to determine whether the program is achieving its goals, whether it is operationally compliant, and whether there are elements that need modification. Assessments may involve surveys of providers and patients regarding their understanding of important safety information and/or registries with patient outcome information. They may also evaluate REMS compliance by examining whether the drug is shipped only to enrolled prescribers, as well as checking the amount of drug shipped versus the number of patients at a site. It is difficult, however, to measure impact on safety, especially for new drugs if they were never on the market without the REMS program. REMS assessments are not routinely published or widely communicated, and it is therefore difficult to independently assess their contribution to enhanced patient safety.

Oncology Health Care Provider Perspective

At the July 2011 workshop, all members of the oncology health care team expressed concerns that REMS programs might create undue burdens for providers and detract from patient care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Challenges and Stakeholder Perspectives

Hematology/oncology practices have identified significant challenges to REMS implementation, including the following that were highlighted at the workshop:

|

Abbreviations: ETASU, Elements to Assure Safe Use; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Experience in the Administration and Safety Monitoring of Chemotherapeutic Agents

Cancer treatment involves use of therapies that carry serious toxicities and risks. Oncologists, oncology nurses, and oncology pharmacists receive unique training in administering chemotherapeutic agents, addressing complex drug safety issues, and managing other aspects of oncology care.

In the oncology private practice setting, with an average of 8.6 full-time equivalent physicians and 1.9 chemotherapy administration staff per physician, 2009 data indicate that one chemotherapy staff member administers, on average, 3,000 infusions per year.11 Managing patient safety and drug toxicity is an integral part of daily oncology practice. The oncology community has expressed concerns about the increased burden and redundancy of REMS programs for many of the oncology-specific treatments and supportive care drugs used in daily practice.

Chemotherapy-related toxicities are handled through a variety of established safety-based clinical practice tools, including treatment guidelines, laboratory testing, patient education, quality measurement tools, and informed consent. Clinical guidelines include information about chemotherapy risks and benefits in the context of treatment recommendations. In addition, ASCO and the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) have published a joint statement articulating standards for the safe delivery of chemotherapy.12,13

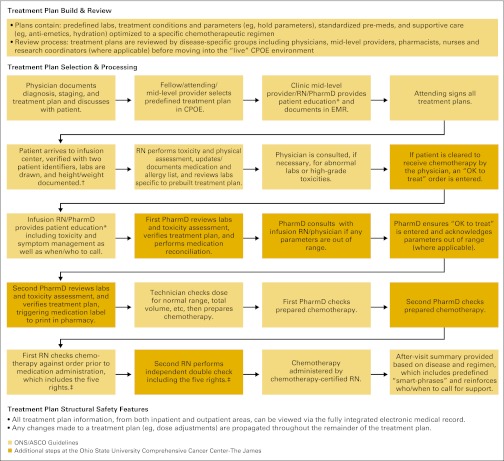

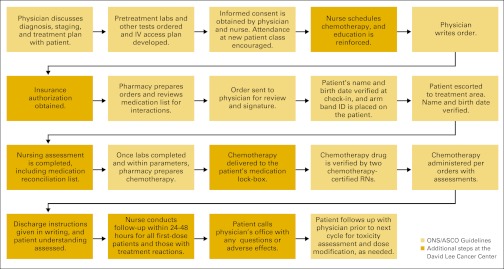

Though specific practices around the country can differ, chemotherapy administration involves an extensive system of checks and balances designed to inform the patient of risks and confirm the delivery of the proper medication, including chemotherapy ordering, verification, preparation, and administration. Figures available online show checks and balances implemented at an ambulatory care site (Appendix Figure A2, online only) and a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center (Appendix Figure A3, online only) based on current professional guidelines.

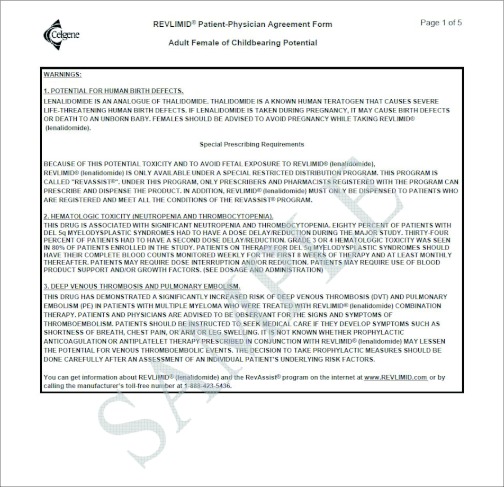

Unintended Consequences of Oncology REMS

REMS programs can have unintended consequences that cause administrative burden and negatively affect oncology clinical practice. Examination of existing REMS in oncology illustrates the frequency with which they duplicate standard oncology practices, such as pregnancy testing, as well as patient counseling and educational materials. Duplication requires additional physician, nurse, and pharmacist time, taking resources away from direct patient care. Table 3 summarizes each of the necessary steps to prescribe one REMS drug, lenalidomide (Revlimid). Even if each step requires only a few minutes of provider time per patient, the total investment is substantial.

Table 3.

Revlimid: A Study in Timing

| Initial Prescription | |

|---|---|

| Action | Time |

| Office prints provider registration form from www.revlimid.com, completes form, faxes it to RevAssist, and awaits confirmation | 15 min |

| Nurse downloads RevAssist software from www.revlimid.com | 5 min |

| If female patient is of childbearing potential, obtain two negative pregnancy tests 10-14 days and 24 hours prior to treatment initiation | |

| Nurse prints out the patient-physician form (PPAF) from RevAssist Online | 5 min |

| Physician provides mandatory counseling during office visit, and both patient and physician sign the PPAF | 30 min |

| Nurse faxes PPAF to RevAssist and awaits confirmation | 1.5-2 h |

| Office instructs patient to complete patient phone survey | 15 min |

| Nurse completes prescriber phone survey and receives authorization number | 5 min |

| Nurse downloads patient prescription form from RevAssist Online | 5 min |

| Nurse records authorization number on patient prescription form | 5 min |

| Nurse chooses Revlimid contract pharmacy from list on patient prescription form | 5 min |

| Nurse faxes patient prescription form to Revlimid contract pharmacy | 5 min |

| Contract pharmacy verifies the patient's insurance coverage | |

| If chosen contract pharmacy does not accept patient's insurance, pharmacy contacts provider's office and recommends an alternative contract pharmacy | 5-10 min |

| If patient has no insurance or is underinsured, provider's office contacts Celgene assistance program to help cover patient costs | 30 min |

| Celgene assistance program contacts patient to obtain financial information | 24 h-1 wk |

| After reimbursement/patient assistance is confirmed, prescription is processed by contract pharmacy | |

| Contract pharmacy ships 28-day supply | 24-72 h |

| Subsequent Prescriptions | |

|---|---|

| Action | Time |

| Contract pharmacy faxes prescription request form to provider's office each month for refills | |

| Nurse completes prescriber phone survey, verifies patient counseling and negative pregnancy test in past 7 days (for women of child bearing potential) and receives refill authorization number | 15 min |

| Nurse records authorization number on the prescription refill request form | 5 min |

| Nurse takes prescription refill request form to prescriber for signature | 1 min |

| Nurse faxes prescription refill request form to contract pharmacy | 15 min |

| Nurse instructs patient to complete patient phone surveys as scheduled by RevAssist (monthly for women of childbearing potential; all others, every 6 months) | 15 min |

| Contract pharmacy ships drug to the patient | 24-72 h |

This timing study was completed by the David Lee Cancer Center, Charleston Area Medical Center Health Systems, Charleston, WV. Enrollment in the RevAssist program was done without submitting information through the online system. An online system14 is available to reduce time to complete these required steps.

Certification in REMS programs can become overly burdensome, with some oncology health care providers required to obtain certification in as many as 21 separate programs. Some REMS programs, such as the erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) REMS, also have a requirement to recertify every 3 years even though there may not be any new safety information. Moreover, REMS programs with restricted distribution requirements may increase overall costs, as well as decrease provider efficiency and effectiveness. Restricted distribution programs have the paradoxical potential to increase risk because they may require use of different pharmacy providers, creating fragmented medical records. Overall, it is unclear whether the potential risks and costs of these complex REMS programs outweigh the desired patient safety benefit.

In addition, REMS materials for patients do not balance safety with efficacy, potentially causing confusion and fear on the part of patients facing difficult treatment decisions. REMS materials often do not (1) include information on benefits or consideration of alternative therapies, (2) reflect unique needs of cancer patients, or (3) provide information to fit the educational needs of specific patients. Ethical concerns have been raised regarding patient forms that explicitly require a signature demonstrating comprehension, even though the materials are often not written at average literacy levels. Privacy concerns arise when the forms release confidential information to the manufacturer in order to access the drug.

Plain language risk communication written at the average American literacy level is important so that patients can comprehend educational materials they receive.15 Flesch-Kincaid grade level analyses presented at the workshop found that REMS educational materials for patients often exceed medical literacy. Darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp) material is written at grade 8.2, lenalidomide (Revlimid) at grade 9.6, and some pieces of the fentanyl (Onsolis) REMS are written at the college level (Appendix Figure A4, online only).16 It is unlikely that the average patient, especially in the context of confronting a life-threatening illness, can absorb all the safety information and requirements needed for access to their medication. Although unintentional, REMS educational materials at high health literacy levels can then create disparities in care.

Stakeholder Surveys on REMS Implementation

The frustration over REMS felt by many providers has been supported by multiple stakeholder surveys. In a May 2011 ASCO member survey, 41% of the 1,311 respondents did not believe REMS enhanced patient safety. Only 11% said REMS programs meet their patient safety goals. A majority (56%) said the negative impact of REMS administrative requirements outweigh any potential benefits to patients; 14% said REMS interfere with safety measures already used by the practice (Appendix Table A3, online only). Fifty-six percent of respondents said that additional staff or staff time have been added to their practices in order to meet REMS requirements, and 42% said that less time is spent with patients in order to satisfy REMS.

Similar results were obtained by two other surveys: a Hematology Oncology Pharmacy Association (HOPA) survey and a National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) survey. Of the 152 respondents to the HOPA survey, 75% said patient/clinical time is redirected because of REMS requirements, and 80% agreed that REMS processes are inefficient.17 HOPA members also expressed concerns regarding the lack of REMS standardization. Of the 570 NCCN respondents, the majority agreed or strongly agreed that REMS interfere with patient care (55%), drive use toward drugs not subject to REMS (60%), and create or increase disparities in care (53%).2

Industry Perspective

The FDA's REMS regulatory authority is limited to the manufacturer of the product. Manufacturers may be required to create complex programs to monitor each provider and patient using their products. Pharmaceutical industry stakeholders also express concerns about the impact of REMS on drug development and the burden on the health care system.

One issue involves timing of REMS development. REMS discussions between the drug manufacturer and FDA typically begin toward the end of FDA review of a drug application for a new indication. This leaves little time to obtain input from stakeholders. Even if such discussions occur earlier, any potential agreements reached between the two parties are subject to reassessment during the drug application review. The absence of a standardized process for developing and evaluating REMS increases the uncertainty and burden of developing, dispensing, and using the drug in question. Development of a more systematic process would enable sponsors to plan collection of specific data in the context of clinical development that could later support REMS discussions with the FDA.

In addition, manufacturers often encounter legal or regulatory barriers to program implementation. For example, manufacturer access to information on prescribing patterns and involvement in REMS-required patient and provider monitoring may run counter to federal and state privacy laws.

Finally, for programs such as RevAssist and the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program, the FDA requires the manufacturers to ensure that third parties, such as providers and distributors, are compliant with such programs, but manufacturers do not have any legal authority over third-party actions or decisions. This discrepancy in FDA regulatory authority creates an unclear landscape for REMS compliance. It also limits the participation of nonindustry-affiliated providers and patient advocates in the development, implementation and assessment of REMS programs.

A Path Forward

Although the challenges associated with REMS are multifaceted, workshop participants discussed a number of ways to ensure achievement of safety-related goals, appropriately communicate risks and benefits, and decrease burden. The following recommendations would help improve development and implementation of REMS programs.

Standardization of REMS processes is an important way to ensure a consistent approach to how REMS are developed. Consideration should be given to when a REMS is warranted, which elements are necessary, and how they should be implemented given the specific providers, clinical settings, and patient populations likely to use the drug.

REMS programs should only supplement, not duplicate, the existing education, experience, and clinical practice tools providers have to manage a safety concern. REMS programs for oncology drugs that focus on safety issues already managed by oncology professionals could be modified to reduce redundancy without jeopardizing patient safety. A standardized algorithm can be developed to account for the education, training, and experience of providers, as well as safety measures already used; this algorithm could tailor REMS education requirements to be less burdensome for any specialty that regularly manages a particular risk. For broader populations, providers should be able to demonstrate a competency by testing out of education programs. Provider education should be required only for new and unique safety signals that affect clinical decision making and are not already managed in clinical practice.

Stakeholder involvement is crucial to REMS development, particularly in the standardization process of REMS and in the development of the practical clinical applications of REMS programs. Therefore, in the short term, stakeholders should be engaged in an open forum. Possible outlets for this engagement might be public advisory committee meetings or meetings with professional societies and patient advocacy organizations. Understanding each of these perspectives and the rationale for decision making in creation of the REMS before it is in place makes it more likely that the resulting program will work for all the stakeholders involved.

Continued integration of risk mitigation into the health care delivery system will ensure consistent implementation. It is important for manufacturers and the FDA to provide public safety messages and to work with professional societies to communicate messages, educate professionals, and assess the understanding and implementation of safety measures. The societies involved in organizing the workshop (ASCO, American Society of Hematology, HOPA, NCCN, ONS and the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists) expressed willingness to assume responsibility for disseminating safety information and assisting members in taking steps to ensure safe delivery of therapies. For example, consolidating drug safety education into annual and thematic meetings is a less burdensome approach than individual, isolated educational programs for each drug.

Whereas the FDAAA provides regulatory authority only over the manufacturer, workshop organizers believe that the responsibility to implement safety standards in practice can best be fulfilled by providers. REMS may be useful when therapies pose uncommon or unique toxicities with which the provider team may not be familiar. Provider and patient organizations have a variety of tools to increase patient safety and assess quality measures. It is helpful to focus provider attention on implementation of measures that may not be in place to mitigate the particular risk. Providing drug safety information that is integrated into the health care system would allow health care providers and patients to utilize the most current information in shared decision making. In addition, professional societies are best equipped to work with health information technology developers to create systems to prompt providers and patients about safety concerns. These activities reside better with providers than with manufacturers. Demonstrating steps that build safety mitigation into daily practice should be sufficient to avoid provision of patient information to manufacturers.

Ongoing dialogue between stakeholders is imperative to the future of drug safety management. This ASCO workshop, which included stakeholders from across the health care landscape, suggests subsequent similar forums and working groups may be an effective way to chart a path forward for REMS. Smaller groups could focus on specific aspects of REMS and explore other risk management options, including the use of informatics to improve education and assessments and how to leverage best practices currently in place in order to refine REMS programs.

Since the July 2011 workshop, the FDA has made changes to certain REMS programs, including the removal of several medication guide–only REMS and the conversion of romiplostim (Nplate) and eltrombopag (Promacta) from REMS with ETASUs to REMS with only communication plans.8 As part of the fifth reauthorization of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), the FDA has also proposed reassessment of REMS.6 They have made a commitment to “measure the effectiveness of REMS and standardize and better integrate REMS into the healthcare system.”18(p25) The agency plans public meetings with all stakeholders “with the goal of reducing the burden of implementing REMS on practitioners, patients, and others in various healthcare settings.”18(p26)

An alternative approach to REMS decision making, which utilizes the principles of standardization with the intent of reducing burden and improving access to and safe use of medications, was presented briefly at the workshop (Appendix Table A4, online only).

Conclusion

The central concern of health care providers, the FDA, manufacturers, patients, and other stakeholders is the delivery of safe, effective care. Experience with REMS has demonstrated that despite a clearly positive intent, the program design does not enhance and may interfere with this important goal and, in many cases, may actually detract from patient care as a result of administrative burden and redundancy. Patient safety and understanding can be improved by developing risk communication programs that consider provider education, training, and experience; integrate into health care systems; and provide more appropriate educational materials for patients.

The FDA has proposed taking meaningful steps in the context of PDUFA reauthorization to standardize and integrate REMS into the health care system. The provider community and professional societies are eager to build on this opportunity.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the contributions of the many people who helped plan the workshop, presented information at the workshop, and contributed to this article. The Workshop Planning Committee included: Joseph O. Jacobson, MD (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute); Matt Farber, MA, and Christian Downs, MHA, JD (Association of Community Cancer Centers); J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, MACP, and Rebecca Kirch, JD (American Cancer Society); Stephanie Kaplan (American Society of Hematology); Joshua Benner, PharmD, ScD, and Sally Cluchey, MS (Brookings Institute); Jeff Allen, PhD (Friends of Cancer Research); Christopher Bowden, MD (Genentech); Sharyl Nass, PhD (Institute of Medicine); William P. McGivney, PhD (National Comprehensive Cancer Network); Nicole Tapay, JD (National Coalition of Cancer Survivors); Lynne McGrath, PhD, MPH (Novartis); Elizabeth Evans, RN, BSN, MPM, FACMPE, CPHQ, CPHIMS, and Michele Dietz, RN, MSN (Oncology Nursing Society); Melissa Finnegan and Dayna McCauley, PharmD, BCOP (Society of Gynecologic Oncologists). The Workshop presenters included: Joseph O. Jacobson, MD (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute); Darshan Wariabharaj (Novartis); James N. Frame, MD (David Lee Cancer Center); Wendy H. Vogel, MSN, FNP, AOCNP (Kingsport Hematology/Oncology); Joseph A. Cordaro, PharmD, MBA (AstraZeneca); Jane Perlmutter, PhD (Gemini Group); Philip E. Johnson, MS, RPh, FASHP (Moffitt Cancer Center); Steven L. Allen, MD, FACP (North Shore University Hospital); Rekha Garg, MD, MS (Amgen); Robin Zon, MD, FACP (Michiana Hematology Oncology); Niesha Griffith, MS, RPh, FASHP (Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association); and Tracy Holliman (Celgene Corporation). Dave Levitan (science writer) helped prepare this article. Jo Thomas, RN, OCN (David Lee Cancer Center) provided expertise to develop Table 2. Christopher Schuler, PharmD Candidate and Pam McDevitt, PharmD, BCOP (David Lee Cancer Center) developed Table 3.

Appendix

Table A1.

REMS for Various Hematology-Oncology Drugs, Current as of October 1, 2011

| Drug | Manufacturer | Indications | REMS Element |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Guide | Communication Plan | ETASU | Implementation System | |||

| Active Treatment Drugs | ||||||

| Eculizumab (Soliris) | Alexion Pharmaceuticals | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria to reduce hemolysis | X | X | ||

| Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome to inhibit complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy | ||||||

| Ipilimumab (Yervoy) | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma | X | |||

| Lenalidomide (Revlimid) | Celgene | Transfusion-dependent anemia caused by low or intermediate risk myelodysplastic syndrome associated with a deletion 5q abnormality with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities Multiple myeloma (combined with dexamethosone) in patients who have received at least one prior therapy |

X | X | X | |

| Nilotinib (Tasigna) | Novartis | Newly diagnosed Ph+ CML in chronic phase Chronic- and accelerated-phase Ph+ CML that is resistant or intolerant to previous therapy that included imatinib |

X | X | ||

| Thalidomide (Thalomid) | Celgene | Newly diagnosed multiple myeloma | X | X | X | |

| Vandetanib (Caprelsa) | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals | Symptomatic or progressive medullary thyroid cancer with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease | X | X | X | X |

| Supportive Care Drugs | ||||||

| Denosumab (Prolia) | Amgen | Osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture Osteoporosis that is resistant or intolerant to other therapy |

X | X | ||

| Darbepoeitin alfa (Aranesp) | Amgen | Anemia in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies in whom anemia is due to the effect of concomitant myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and upon initiation, there is a minimum of 2 additional months of planned chemotherapy Aranesp is indicated for the treatment of anemia due to chronic kidney disease, including patients on dialysis and patients not on dialysis |

X | X | X | X |

| Epoetin alfa (Epogen, Procrit) | Amgen (Epogen), Ortho Biotech Products (Procrit) | Anemia in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies in whom anemia is due to the effect of concomitant myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and upon initiation, there is a minimum of 2 additional months of planned chemotherapy Anemia caused by chronic kidney disease, including patients on dialysis and not on dialysis to decrease the need for red blood cell transfusion |

X | X | X | X |

| Eltrombopag (Promacta)* | GlaxoSmith Kline | Thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura at risk for bleeding who have had insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy | X | X | X | |

| Romiplostim (Nplate)* | Amgen | Thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura at risk for bleeding who have had insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins or splenectomy | X | X | X | X |

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ETASU, elements to assure safe use; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome positive; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Since October 1, 2011, changes have been made to these REMS programs.8

Table A2.

Enrollment and Registration Requirements for REMS, Current as of October 1, 2011

| Drug | Manufacturer | Enrollment and Registration Requirements |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescriber | Outpatient Pharmacy | Inpatient Pharmacy | Patient | Distributor | ||

| Active Treatment Drugs | ||||||

| Eculizumab (Soliris); Soliris OneSource Program, 1-888-765-4747, www.solirisrems.com/ | Alexion Pharmaceuticals | Must enroll in the program Must counsel patients about the risk of meningococcal infection and ensure patients are vaccinated |

Must enroll in the program | |||

| Lenalidomide (Revlimid); RevAssist (RevAid in Canada), 1-888-423-5436, www.RevAssistOnline.com | Celgene | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | ||

| Thalidomide (Thalomid); STEPS Program (RevAid in Canada), 1-888-423-5436 | Celgene | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | |||

| Vandetanib(Caprelsa) Vandetanib REMS Program1-800-236-9933, http://www.caprelsarems.com/ | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals | Must enroll in the program Must complete training program |

Must enroll in the program Must complete training program Only dispensed through restricted distribution program | |||

| Supportive Care Drugs | ||||||

| Darbepoeitin alfa (Aranesp), Epoetin alfa (Epogen, Procrit); ESA APPRISE REMS Program, 1-866-284-8089,www.esa-apprise.com | Amgen (Aranesp, Epogen), Ortho Biotech Products (Procrit) | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | |||

| Eltrombopag (Promacta)*; Promacta Cares, 1-877-977-6622, www.promactacares.com | GlaxoSmith Kline | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | |

| Romiplostim (Nplate)*; Nplate NEXUS Program, 1-877-675-2831, www.nplatenexus.com | Amgen | Must enroll in the program | Must enroll in the program | |||

Abbreviations: ESA, erythropoiesis stimulating agent; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Since October 1, 2011, changes have been made to these REMS programs.8

Table A3.

Selected Survey Results from the American Society of Clinical Oncology Survey on REMS

| Survey Question | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| What type of organization best describes your practice? | ||

| Academic | 571 | 44 |

| Private practice | 417 | 32 |

| Other, please specify | 127 | 10 |

| Hospital, nonacademic | 122 | 9 |

| Private practice, staff model (eg, Kaiser) | 42 | 3 |

| Government agency | 32 | 2 |

| Total | 1,311 | 100 |

| Are you familiar with Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS)? (Respondents who answered “no” were not included in the following question) | ||

| Yes | 1104 | 84 |

| No | 207 | 16 |

| Total | 1311 | 100 |

| Do you prescribe medications that require one or more REMS elements and/or do you participate in aspects of a REMS program in a clinical setting? (Respondents who answered “no” were not included in the following four questions) | ||

| Yes | 937 | 85 |

| No | 168 | 15 |

| Total | 1105 | 100 |

| In your experience, what is the impact of REMS with respect to patient safety? | ||

| Some elements enhance, while some do not enhance patient safety | 457 | 49 |

| Does not enhance patient safety | 381 | 41 |

| Meets the goal of enhancing patient safety | 99 | 11 |

| Total | 937 | 100 |

| What is the administrative impact of REMS with respect to clinical practice? | ||

| The impact of the administrative requirements outweigh any potential benefit | 526 | 56 |

| There is impact, but the benefits to patients with respect to safety outweigh the resources needed to administer various REMS programs | 239 | 26 |

| The impact of REMS interferes with patient safety measures already implemented in the clinical setting | 129 | 14 |

| No impact on my clinical practice | 43 | 5 |

| Total | 937 | 100 |

| What steps has your practice taken to manage the impact of REMS programs? (Check all that apply) | ||

| Staff/staff time has been added to the practice in order to account for REMS administrative requirements | 502 | 56 |

| My staff and/or I spend less time with my patient in order to have the resources to manage the REMS programs | 375 | 42 |

| There are drugs I will not prescribe due to aspects of the associated REMS program | 309 | 35 |

| REMS materials make it easy for my practice to update educational materials, consent forms and important patient talking points | 126 | 14 |

| Other, please specify | 86 | 10 |

| Fewer new patient have been accepted in order to have the resources to manage the REMS programs | 58 | 6 |

| Have you attempted to quantify the impact in FTEs, change in prescribing patterns, time away from patients, or decreased patient load? | ||

| No | 827 | 93 |

| Yes | 67 | 7 |

| Total | 894 | 100 |

| Somewhat Trusted |

Very Trusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| To what extent do you view the following stakeholders as a trusted source of information regarding the clinical management of a safety issue at the practice level? (All respondents were asked this question) | ||||

| Peer-reviewed scientific journal | 263 | 20 | 1011 | 77 |

| Professional society notifications | 370 | 28 | 856 | 65 |

| FDA notifications | 399 | 30 | 831 | 63 |

| Colleagues | 757 | 58 | 362 | 28 |

| Industry (manufacturer) notifications/Dear Doctor letters | 708 | 54 | 242 | 18 |

| Health system notifications | 558 | 43 | 146 | 11 |

| Group Purchasing Organizations (or others in the supply chain) notifications | 265 | 20 | 45 | 3 |

| Patient | 166 | 13 | 20 | 2 |

| News, including mass media and trade press | 123 | 9 | 6 | 0 |

Survey was administered during May 2011 and received a total of 1,311 complete responses.

Abbreviations: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Table A4.

Decision Tool for an Alternative REMS Approach for Hematology/Oncology Products

| The workshop organizers presented a suggested approach that involves a decision tool to guide decision making about REMS development and implementation for hematology/oncology products. The tool would place each drug into one of three possible levels: |

| Level 1 would apply to drugs with toxicities similar to those already well managed in clinical practice; this would include the majority of oncology drugs. Level 1 drugs would not need an REMS. The FDA and the drug manufacturer would provide standard information, but no changes to standard practice would be required. |

| Level 2 would apply to drugs that carry risks different from common toxicities. These toxicities, however, are manageable given appropriate evidence-based information because of safety measures already common to clinical practice. An REMS program for a level 2 drug would involve a core set of safety information developed by the FDA and the drug manufacturer. The oncology community could then assist in further developing and disseminating important information through various education and communication vehicles. If applicable, laboratory testing or other safe-use procedures could be incorporated into an EHR. |

| Level 3 would apply to drugs that would not be approved in the absence of risk mitigation strategies. Level 3 drugs carry serious, unique risks that should be highlighted for providers and patients and cannot easily be managed by existing practice measures. This could also apply to drugs that carry a specific risk not familiar to a given provider population. REMS programs to manage these drugs should integrate drug safety information in real time in a way that assists patient and provider decision making. Examples could include evidence-based guidelines created by professional organizations, decision aids embedded in EHRs, and quality measures to assess comprehension and implementation into practice. |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration: REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Figure A1.

Itinerary of the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) workshop. ETASU, Elements to Assure Safe Use; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Figure A2.

Chemotherapy checks and balances presented at the Oncology REMS Workshop from the David Lee Cancer Center, Charleston Area Medical Center Health Systems, Charleston, WV. ONS, Oncology Nursing Society. (Provided by James N. Frame, MD, FACP). CPOE, computerized physician order entry.

Figure A3.

Chemotherapy checks and balances with an electronic ordering system at a comprehensive cancer center (Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center-The James, Columbus, OH). CPOE, computerized physician order entry; EMR, electronic medical record; ONS, Oncology Nursing Society; PharmD, doctor of pharmacy; RN, registered nurse. (*) Patient education documents are developed internally. Education is always provided verbally and reinforced with written documents. (†) Body surface area automatically calculated upon entry of height and weight. (‡) Five rights: patient, drug, dose, route, time.

Figure A4.

Text extracted from REMS materials to illustrate content written at a high health literacy level. Example 1 (A) is a list of warnings from the first page of every Revlimid patient-physician agreement form (Celgene: Revlimid (lenalidomide) 1.16 risk management plans: NDA 21-880 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UCM222644.pdf). Example 2 (B) is the Patient Authorization for Disclosure and Use of Health Information Statement from the FOCUS (Full Ongoing Commitment to User Safety) program for Onsolis (Onsolis fentanyl buccal soluble film, page 83. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022266s000PrescriberInfo.pdf). The Revlimid document was approved on August 3, 2010 and is still in use; the Onsolis document was approved on July 16, 2009 and was discontinued on December 28, 2011 after FDA adoption of a shared system REMS for transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl products (US Food and Drug Administration: Approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm). FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Darshan Wariabharaj, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation (C); Rekha Garg, Amgen (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: Steven L. Allen, Allos (C), Celgene (C) Stock Ownership: Darshan Wariabharaj, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; Rekha Garg, Amgen; Steven L. Allen, Bristol Myers Squibb Honoraria: Wendy H. Vogel, Celgene, Lily, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, Millennium, Pfizer; Steven L. Allen, Celgene Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

Author Contributions

Conception and design: James N. Frame, Joseph O. Jacobson, Niesha Griffith, Darshan Wariabharaj, Rekha Garg, Robin Zon, Cynthia L. Stephens, Steven L. Allen

Administrative support: Alison M. Bialecki, Cynthia L. Stephens, Suanna S. Bruinooge

Provision of study materials or patients: James N. Frame, Joseph O. Jacobson, Niesha Griffith

Collection and assembly of data: James N. Frame, Joseph O. Jacobson, Niesha Griffith, Darshan Wariabharaj, Cynthia L. Stephens, Alison M. Bialecki

Data analysis and interpretation: James N. Frame, Wendy H. Vogel, Darshan Wariabharaj, Rekha Garg, Cynthia L. Stephens, Alison M. Bialecki, Suanna S. Bruinooge

Manuscript writing: James N. Frame, Wendy H. Vogel, Niesha Griffith, Darshan Wariabharaj, Rekha Garg, Cynthia L. Stephens, Alison M. Bialecki, Suanna S. Bruinooge, Steven L. Allen

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Accelerated Approval of New Drugs for Serious or Life-Threatening Illnesses. 21 C.F.R. § 314.500.

- 2.Johnson PE, Dahlman G, Eng K, et al. NCCN oncology risk evaluation and mitigation strategies white paper: Recommendations for stakeholders. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:S7–S27. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/federalfooddrugandcosmeticactfdcact/significantamendmentstothefdcact/foodanddrugadministrationamendmentsactof2007/default.htm.

- 4.Identification of Drugs and Biological Products Deemed to Have Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) for Purposes of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007; Notice. 73 Fed. Reg. No. 60. 2008 Mar 27;:16313–16314. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baciu A, Stratton K, Burke SP, editors. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2007. The Future of Drug Safety: Promoting and Protecting the Health of the Public. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prescription Drug User Fee Act; Public Meeting; Notice of public meeting; request for comments. 76 Fed. Reg. No. 176. 2011 Sep 12;:56201–56205. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choe L. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS). Presented at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Division of Drug Information Webinar; October 24, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration. Approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm.

- 9.Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, Public Law No. 110-85, 121 Stat. 2007. p. 929.

- 10.Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, Public Law No. 110-85, 121 Stat. 2007. p. 926.

- 11.Barr TR, Towle EL. National oncology practice benchmark: An annual assessment of financial and operational parameters—2010 report on 2009 data. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(suppl 2):2s–15s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson JO, Polovich M, McNiff KK, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5469–5475. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson JO, Polovich M, Gilmore TR, et al. Revisions to the 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards: Expanding the scope to include inpatient settings. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:2–6. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celgene. RevAssist for healthcare professionals. http://www.revlimid.com/hcp/RevAssist.aspx.

- 15.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: Ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1436–1443. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogel W. On the ground: Oncology clinical practice and REMS. Presented at the ASCO Workshop on Oncology Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies; July 27, 2011; Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soefie S. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS): Survey results. Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association Newsletter. 2010:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration. PDUFA reauthorization performance goals and procedures fiscal years 2013 through 2017. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/PrescriptionDrugUserFee/UCM270412.pdf.