Abstract

Exposure to organochlorinated pesticides such as dieldrin has been linked to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, endocrine disruption, and cancer, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms of toxicity behind these effects remain largely unknown. Here we demonstrate, using a functional genomics approach in the model eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae, that dieldrin alters leucine availability. This model is supported by multiple lines of congruent evidence: (1) mutants defective in amino acid signaling or transport are sensitive to dieldrin, which is reversed by the addition of exogenous leucine; (2) dieldrin sensitivity of wild-type or mutant strains is dependent upon leucine concentration in the media; (3) overexpression of proteins that increase intracellular leucine confer resistance to dieldrin; (4) leucine uptake is inhibited in the presence of dieldrin; and (5) dieldrin induces the amino acid starvation response. Additionally, we demonstrate that appropriate negative regulation of the Ras/protein kinase A pathway, along with an intact pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, is required for dieldrin tolerance. Many yeast genes described in this study have human orthologs that may modulate dieldrin toxicity in humans.

Key Words: dieldrin, organochlorine, yeast, functional genomics, alternative models.

The persistent and bioaccumulative nature of organochlorinated pesticides (OCPs), combined with their widespread use during the mid to late 20th century, resulted in pervasive environmental contamination that exists to the present day. Dieldrin and aldrin (which is converted to dieldrin in biological systems) were two of the most heavily applied cyclodiene OCPs in the United States, utilized to control insects on corn, cotton, and citrus and to prevent or treat termite infestations (ATSDR, 2002). Dieldrin has been detected in soil, water, air, wildlife, and human samples (reviewed in Jorgenson, 2001) and is found at 159 of the 1363 current or proposed Environmental Protection Agency National Priorities List (NPL) hazardous waste sites. It is currently ranked 18th on the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Priority List of Hazardous Substances, a list of compounds that possibly threaten human health on account of their toxicity and potential for exposure at NPL sites. Although the use of dieldrin has been banned or restricted in many countries, concern remains over its persistence in sediment and potential to bioaccumulate in wildlife and humans. Acute exposure to dieldrin results in antagonism of the GABAA receptor, prompting excessive neurotransmission and convulsions (ATSDR, 2002). In both animals and humans, dieldrin has been linked to cancer (reviewed in ATSDR, 2002; Jorgenson, 2001), Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Richardson et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2013; Weisskopf et al., 2010), and endocrine modulation (reviewed in Jorgenson, 2001), but the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind these effects remain largely unknown.

The conservation of basic metabolic pathways and fundamental cellular processes to humans, as well as unmatched genetic resources, makes the eukaryotic yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae an ideal model system for identifying potential cellular and molecular mechanisms of toxicity. Sequence comparison has identified a close human homolog for much of the yeast genome, with several hundred of the conserved genes implicated in human disease (Steinmetz et al., 2002). The development of a yeast deletion library (Giaever et al., 2002) enables the use of functional toxicogenomics (also known as functional profiling) to determine the importance of individual yeast genes for toxicant susceptibility. Unlike typical gene expression experiments that correlate toxicant exposure to changes in mRNA levels, this approach identifies genes functionally involved in toxicant response. Functional profiling has been utilized to discover yeast genes required for tolerance to a broad array of toxicants, including arsenic, iron, benzene, and more (reviewed in dos Santos et al., 2012). In addition, human homologs or functional orthologs of yeast genes uncovered by this approach have been associated with sensitivity to the same toxicant in human cells (Jo et al., 2009a).

In this study, a genome-wide functional screen identified the genetic requirements for tolerance to the dieldrin OCP in yeast. To our knowledge, it is the first comprehensive report investigating the yeast genes necessary for growth in the presence of a persistent organic pollutant, with the results demonstrating that dieldrin toxicity can be primarily attributed to altered leucine availability. Additionally, both proper regulation of the Ras/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway and components of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex are required for dieldrin tolerance. Many yeast genes involved in dieldrin resistance have human homologs that may also play a role in dieldrin response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, culture, and plasmids.

The diploid yeast deletion strains used for functional profiling and confirmation analyses were of the BY4743 background (MATa/MATα his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0/LYS2 MET15/met15Δ0 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0, Invitrogen). The haploid yeast LEU2 MORF overexpression strain was of the Y258 background (MATa, pep4-3, his4-580, ura3-53, leu2-3,112, Open Biosystems). The BAP2 HIP FlexGene expression vector, the B180 plasmid (GCN4-lacZ), and linearized pRS305 plasmid containing the LEU2 gene were transformed into the BY4743 background. For deletion pool growth, cells were grown in liquid rich media (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, YPD), whereas confirmation assays were performed in YPD or liquid synthetic complete media lacking leucine (0.68% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.077% CSM-Leu dropout mixture, 2% dextrose, SC-Leu) at 30°C with shaking at 200 revolutions per minute (rpm). Starvation media (SD-N) was composed of 0.68% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and 2% dextrose. Protein overexpression was induced as in North et al. (2011) using liquid rich media containing 2% galactose and 2% raffinose (YPGal+Raf).

Dose-finding and growth curve assays.

Dose-finding and growth curve experiments were performed as in North et al. (2011). Briefly, cells were grown to mid-log phase, diluted to an optical density at 600nm (OD600) of 0.0165, and dispensed into nontreated polystyrene plates. Dieldrin (a gift from N.D.) stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to the desired final concentrations (1% or less by volume) with at least two technical replicates per dose. Based upon literature searches for dieldrin toxicity in human cells (Ledirac et al., 2005), the dieldrin yeast dose-response curve was narrowed to 200–800μM, which was examined in three independent experiments. Plates were incubated in Tecan microplate readers set to 30°C with shaking and OD595 measurements were taken every 15min for 24h. The raw absorbance data were averaged, background corrected, and plotted as a function of time. The area under the curve was calculated with Apache OpenOffice Calc and expressed as a percentage of the untreated control.

Functional profiling of the yeast genome.

Growth of the deletion pools, genomic DNA extraction, barcode amplification, Affymetrix TAG4 array hybridization, and differential strain sensitivity analysis (DSSA) were performed as described (Jo et al., 2009b). Briefly, pools of homozygous diploid deletion mutants (n = 4607) were grown in YPD at various dieldrin concentrations for 15 generations and genomic DNA was extracted using the YDER kit (Pierce Biotechnology). The DNA sequences unique to each strain (barcodes) were amplified by PCR and hybridized to TAG4 arrays (Affymetrix), which were incubated overnight, stained, and then scanned at an emission wavelength of 560nm with a GeneChip Scanner (Affymetrix). Data files are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database.

Overenrichment and network mapping analyses.

Significantly overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) and MIPS (Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences) categories within the DSSA data were identified by a hypergeometric distribution using the Functional Specification resource, FunSpec, with a p value cutoff of 0.001 and Bonferroni correction. For the network mapping, fitness scores for strains displaying sensitivity to at least two doses of dieldrin were mapped onto the BioGrid S. cerevisiae functional interaction network using the Cytoscape software. The jActiveModules plugin then identified subnetworks of genes enriched with fitness data, and the BiNGO plugin assessed overrepresentation of GO categories within these subnetworks.

Analysis of relative strain growth by flow cytometry.

Assays were performed as in North et al. (2012), with slight modifications. Briefly, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged wild-type and untagged mutant strains were grown overnight in YPD, diluted to 0.5 OD600, and mixed in approximately equal numbers. Cells were inoculated into YPD or SC-LEU at 0.00375 OD600 in microplate format, treated with dieldrin, and grown for 24h at 30°C with shaking at 200rpm. Approximately 20,000 cells per culture were analyzed at T = 0 and T = 24h using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. GFP-expressing wild-type cells were distinguishable from untagged mutant cells. The percentages of wild-type GFP and untagged mutant cells present in the cultures were used to calculate a ratio of growth for untagged cells in treated versus untreated samples. Statistically significant differences between the means of three independent DMSO-treated and dieldrin-treated cultures were determined using Student’s t-test. Raw p values were corrected for multiplicity of comparisons using Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

Leucine uptake assays.

Leucine transport was measured as in Heitman et al. (1993), with slight modifications. Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted, incubated for 4h at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase, and washed with wash buffer (10mM sodium citrate, pH 4.5). Cells were resuspended in 10mM sodium citrate (pH 4.5)-20mM (NH4)2SO2-2% glucose and the OD600 was measured. Import reactions contained resuspended cells, DMSO or dieldrin at a final concentration of 460μM, and 15.9 μl of L-[14C]leucine (53 mCi/mmol, 5μM final concentration) in a total of 3ml. Aliquots (0.5ml) of the import reaction were taken at 0, 2, 5, 10, 30, and 60min and vacuum filtered through 25mm Whatman GF/C glass microfiber filters presoaked in wash buffer. Filters were washed four times with 0.5ml wash buffer containing 2mM unlabeled L-leucine and bound radioactivity was quantified in Safety-Solve counting cocktail using a Beckman LS-6000IC liquid scintillation counter.

Amino acid starvation analyses.

Cells harboring the B180 plasmid (containing a GCN4-lacZ reporter) were cultured overnight in SC-ura 2% dextrose, diluted to 0.25 OD600, and spun down at 3500rpm following a 5-h period of growth. A wash and resuspension occurred in either SC-ura 2% dextrose or starvation media (SD-N), upon which cells were aliquoted to a microplate and treated with DMSO or the dieldrin IC20 (460μM) for 3h. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed with the yeast β-galactosidase assay kit (ThermoScientific) and Miller units were calculated with the equation (1000 × A420)/(minutes of incubation × volume in milliliters × OD660).

RESULTS

A Genome-Wide Screen Identifies Mutants With Altered Growth in the Presence of Dieldrin

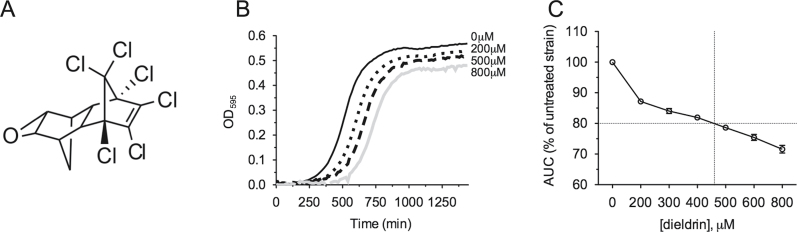

Growth curve assays were performed to determine the toxicity of dieldrin to yeast (Fig. 1B), based upon knowledge that (1) dieldrin causes physiological effects in human cell culture systems at 25–50μM (Ledirac et al., 2005) and (2) the cell wall and abundant multidrug transporters often lend yeast resistance to chemical insult. From the growth curves, the IC20, a concentration determined as appropriate for use in the functional screen (Jo et al., 2009b), was calculated as 460μM (Fig. 1C). To discover genes important for growth in dieldrin, pools of yeast homozygous diploid deletion mutants (n = 4607) were grown for 15 generations at the IC20 (460μM), 50% IC20 (230μM), and 25% IC20 (115μM). A DSSA identified 427 mutants as sensitive and 320 mutants as resistant to at least one dose of dieldrin (Supplementary table 1), with the top 25 sensitive strains at the IC20 shown in Table 1. Strains sensitive to dieldrin were the focus of this study.

Fig. 1.

Dose determination of dieldrin IC20 for functional profiling. (A) The chemical structure of dieldrin. (B) Representative growth curves for the BY4743 wild-type strain treated with dieldrin in YPD media. Curves were performed for 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 800μM dieldrin, but for clarity, only the 200, 500, and 800μM doses are shown. (C) The area under the curve (AUC) at each dose was expressed as the mean and SE of three independent experiments and plotted as a percentage of the untreated control. Dashed lines indicate the dose (460μM) at which growth was inhibited by 20% (IC20).

Table 1.

Fitness Scores for the Top 25 Mutants Identified as Significantly Sensitive to the Dieldrin IC20 (460μM) After 15 Generations of Growth

| Log2 values | Deleted gene | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% IC20 | 50% IC20 | 100% IC20 | ||

| −3.90 | −4.95 | −6.80 | IRA2 | GTPase-activating protein; negatively regulates Ras |

| −4.00 | −4.40 | −6.10 | GYP1 | GTPase-activating protein; involved in vesicle docking |

| −5.60 | −5.65 | BAP2 | High-affinity leucine permease | |

| −3.75 | −4.85 | −5.60 | PDC1 | Major of three pyruvate decarboxylase isozymes |

| −3.10 | −3.95 | −5.25 | YJL120W | Dubious ORF; partially overlaps the verified gene RPE1 |

| −4.90 | −4.50 | −5.05 | PDR5 | Multidrug transporter |

| −4.70 | −5.20 | −5.00 | YCR007C | Putative integral membrane protein |

| −3.10 | −3.10 | −4.90 | IRS4 | Regulates PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels and autophagy |

| −1.30 | −1.60 | −4.90 | SOK2 | Regulator of PKA signal transduction pathway |

| −1.65 | −1.45 | −4.85 | TCB3 | Lipid-binding protein |

| −3.80 | −5.30 | −4.80 | SLT2 | MAPK involved in cell wall integrity and cell cycle progression |

| −4.90 | −4.90 | −4.80 | YML079W | Unknown function; structurally similar to plant storage proteins |

| −4.15 | −4.45 | −4.70 | TIM18 | Component of the mitochondrial TIM22 complex |

| −2.00 | −2.40 | −4.70 | OPI3 | Phospholipid methyltransferase |

| −3.20 | −3.40 | −4.60 | SIS2 | Negative regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 |

| −2.55 | −2.35 | −4.60 | SCJ1 | Homolog of bacterial chaperone DnaJ |

| −4.20 | −3.50 | −4.50 | SIW14 | Tyr phosphatase; involved in actin organization and endocytosis |

| −2.10 | −2.55 | −4.45 | CNB1 | Calcineurin B; the regulatory subunit of calcineurin |

| −2.30 | −2.75 | −4.35 | OSH3 | Oxysterol-binding protein; functions in sterol metabolism |

| −1.90 | −2.85 | −4.25 | UFD2 | Ubiquitin chain assembly factor (E4) |

| −3.05 | −4.90 | −4.10 | IMP2′ | Transcriptional activator; maintains ion homeostasis |

| −3.05 | −2.75 | −4.10 | BRE5 | Ubiquitin protease cofactor; forms complex with Ubp3p |

| −4.00 | −4.30 | −4.00 | SAP4 | Protein required for function of the Sit4p protein phosphatase |

| −2.90 | −3.60 | −4.00 | ECM30 | Nonessential protein of unknown function |

| −2.60 | −2.40 | −4.00 | BST1 | GPI inositol deacylase; negatively regulates vesicle formation |

Note. Fitness scores quantify the requirement of a gene for growth and are defined as the normalized log2 ratio of the deletion strain’s growth in the presence versus absence of dieldrin. A total of 427 genes were important for fitness (i.e., had negative fitness scores) in at least one dieldrin treatment. Supplementary table 1 contains a list of all genes identified as significant by DSSA.

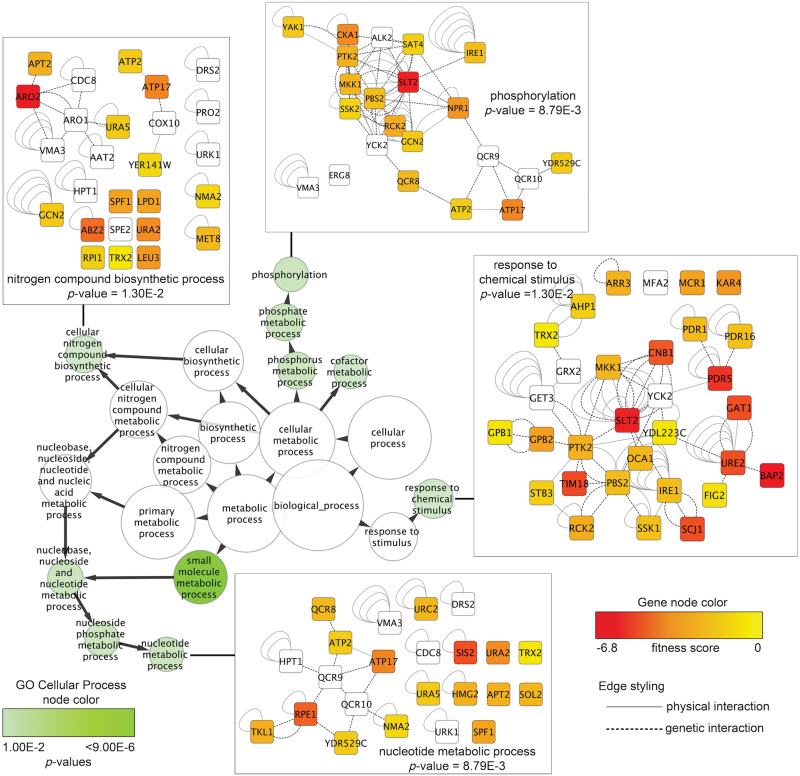

Enrichment Analyses and Network Mapping Identify Attributes Necessary for Dieldrin Tolerance

A list of mutant strains displaying sensitivity to at least two of the dieldrin treatments (n = 219) was analyzed for significantly overrepresented biological attributes using FunSpec. Both GO and MIPS categories were enriched for various classifications at a corrected p value of 0.001, including nitrogen utilization, protein phosphorylation, the PDH complex, negative regulation of Ras signaling, and sensitivity to amino acid analogs (Table 2). For additional insight into the attributes required for dieldrin tolerance, network mapping was performed with the Cytoscape visualization tool and plugins identifying enriched categories. Similar to the FunSpec evaluation, nitrogen processes and phosphorylation were overrepresented within the network data (Fig. 2). These enrichment analyses guided the selection of candidate cellular processes and components for further experimentation.

Table 2.

Genes Required for Growth in the Presence of Dieldrin and Their Associated MIPS or GO Categories

| GO biological process | p value | Genes identified | ka | fb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein folding in endoplasmic reticulum (GO:0034975) | 3.23E-004 | EMC1, JEM1, EMC2, SCJ1 | 4 | 11 |

| Regulation of nitrogen utilization (GO:0006808) | 3.43E-004 | VID30, NPR1, URE2 | 3 | 5 |

| Protein phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | 4.34E-004 | SAT4, GCN2, SLT2, IRE1, CKA1, PBS2, YAK1, PTK2, RCK2, NPR1, SSK2, MKK1, DBF20 | 13 | 133 |

| Negative regulation of Ras protein signal transduction (GO:0046580) | 6.68E-004 | GPB2, IRA2, GPB1 | 3 | 6 |

| MIPS functional classification | p value | Genes identified | ka | fb |

| Regulation of nitrogen metabolism (01.02.07.01) | 7.42E-005 | GAT1, VID30, NPR1, URE2 | 4 | 8 |

| Modification by phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, autophosphorylation (14.07.03) | 1.33E-004 | SAT4, GCN2, SAP4, SLT2, IRE1, CKA1, PBS2, YAK1, PTK2, CNB1, RCK2, SIW14, OCA1, NPR1, SSK2, MKK1, DBF20 | 17 | 186 |

| G1/S transition of mitotic cell cycle (10.03.01.01.03) | 1.77E-004 | SAT4, BCK2, SAP4, CKA1, VHS2, PTK2, SIS2 | 7 | 37 |

| Regulation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis (02.01.03) | 3.05E-004 | RMD5, UBC8, VID30, PFK26, FBP26 | 5 | 19 |

| PDH complex (02.08) | 3.43E-004 | PDB1, LPD1, PDX1 | 3 | 5 |

| Degradation of glycine (01.01.09.01.02) | 6.68E-004 | GCV3, LPD1, SHM2 | 3 | 6 |

| Phosphate metabolism (01.04) | 7.16E-004 | SAT4, RBK1, GCN2, PPN1, YND1, SAP1, SAP4, SLT2, INM1, IRE1, CKA1, PFK26, PBS2, YAK1, FBP26, PTK2, CNB1, RCK2, SIW14, OCA1, NPR1, PEX6, SSK2, LCB4, MKK1, DBF20 | 26 | 401 |

| MIPS phenotypes | p value | Genes identified | ka | fb |

| Sensitivity to other aminoacid analogs and other drugs (92.99) | 3.72E-005 | RVS161, PDR1, LST7, PBS2, PTK2, HMG2, LEU3, TAT2, PDR5 | 9 | 51 |

| Starvation sensitivity (62.10) | 1.64E-004 | RVS161, VID30, SLT2, IRA2, MKK1, ATG13 | 6 | 26 |

Note. A list of strains exhibiting sensitivity to at least two out of the three doses of dieldrin was entered into the FunSpec tool and analyzed for overrepresented biological attributes (see Materials and Methods section).

aNumber of genes in category identified as sensitive to dieldrin.

bNumber of genes in GO or MIPS category.

Fig. 2.

Cytoscape network mapping identifies biological attributes required for dieldrin tolerance. Fitness scores (the difference in the mean of the log2 hybridization signal between DMSO and dieldrin treatment) for strains displaying sensitivity to at least two dieldrin treatments were mapped onto the Saccharomyces cerevisiae BioGrid interaction data set using Cytoscape. A smaller subnetwork (235 genes) was created containing genetic and physical interactions between the sensitive, nonsensitive, and essential genes. Significantly overrepresented (p value cutoff of 0.03) GO categories were visualized as a network in which the green node color corresponds to significance, whereas node size indicates the number of genes present in the category. Edge arrows indicate hierarchy of GO terms. Gene networks corresponding to various GO categories are shown, where node color signifies the deletion strain fitness score (fitness not determined for white nodes) and edge styling defines the interaction between nodes.

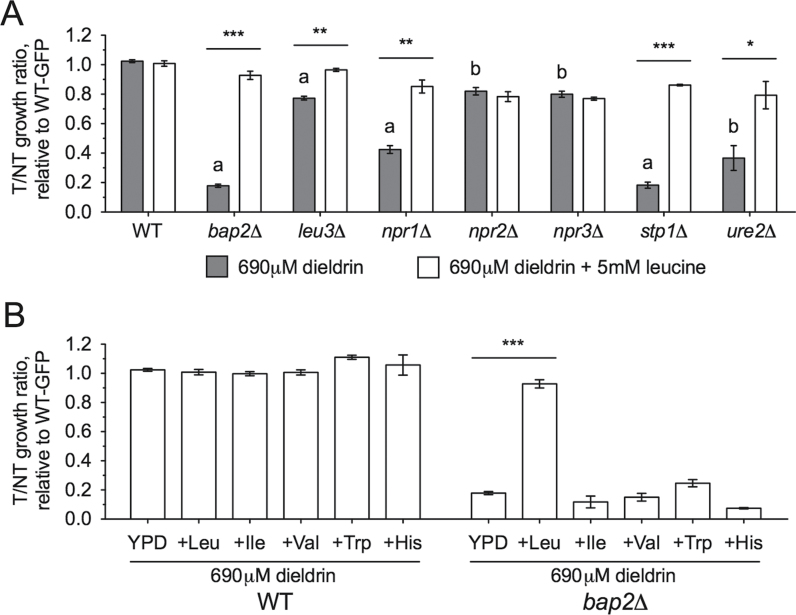

Mutants Defective in Amino Acid Uptake and Nitrogen Signaling Are Sensitive to Dieldrin

Overrepresentation analyses with FunSpec and Cytoscape implicated nitrogen processes as important for dieldrin tolerance. Therefore, we used flow cytometry to assay relative growth of a wild-type strain to mutants deficient in amino acid signaling and uptake, as well as nitrogen utilization. Both DSSA and flow cytometry identified bap2Δ, which lacks a gene encoding for a high-affinity leucine permease, as one of the strains most sensitive to dieldrin (Fig. 3A). Additional amino acid signaling genes were confirmed to be required for dieldrin tolerance, including NPR1 (a kinase that prevents degradation of several amino acid transporters), STP1 (a component of the Ssy1p-Ptr3p-Ssy5p SPS system that transduces extracellular amino acid status), and LEU3 (a transcription factor regulating branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis and amino acid permeases) (Fig. 3A). The NPR2, NPR3, and URE2 genes involved in the cellular response to nitrogen were also identified as necessary for growth in dieldrin (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Dieldrin sensitivity of mutants involved in amino acid or nitrogen processes is reversed by leucine. Deletion mutants were tested for sensitivity to the dieldrin IC25 (690μM) by flow cytometry, in which relative growth of each mutant was compared with a wild-type GFP strain after 24h. Means of the growth ratios (treatment vs. control—T/NT) to wild-type GFP are shown with SE for three independent YPD cultures. Significance values were calculated by Student’s t-test, where a p < 0.001 and b p < 0.01 for dieldrin-treated wild-type versus mutant, whereas ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 for dieldrin versus dieldrin-leucine treatment. (A) Amino acid uptake and signaling mutants, as well as those involved in nitrogen utilization, are sensitive to dieldrin, with most mutants rescued by addition of 5mM leucine. (B) Amino acids related to leucine or transported by Bap2p cannot reverse dieldrin sensitivity in bap2Δ. Leucine, isoleucine, valine, and histidine were added to YPD media at a final concentration of 5mM, whereas tryptophan was present at 2.5mM.

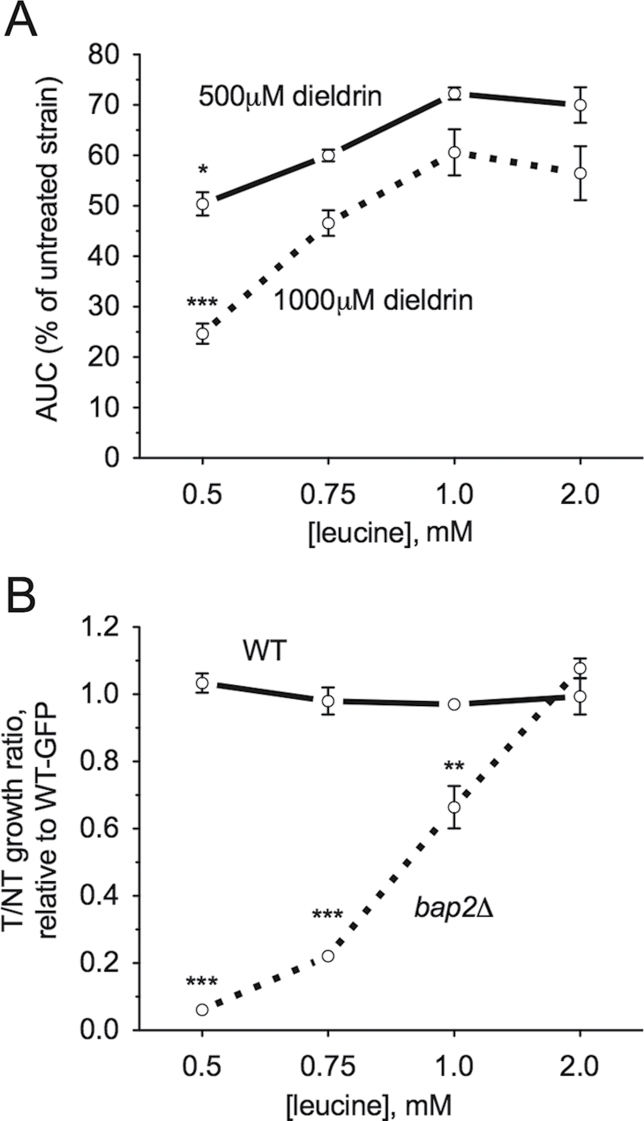

Leucine Availability Is Linked to Dieldrin Toxicity

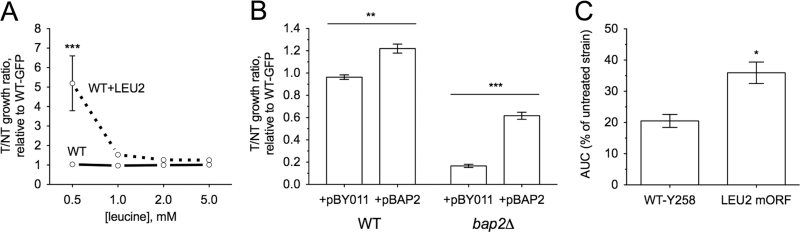

With the determination that bap2Δ (which lacks a high-affinity leucine permease) was sensitive to dieldrin, we hypothesized that supplementation of YPD-dieldrin medium with excess leucine might mitigate the toxicity of dieldrin. Indeed, addition of 5mM leucine reversed the sensitivity not only of bap2Δ but also leu3Δ, npr1Δ, and stp1Δ to dieldrin (Fig. 3A). Although leucine moderately rescued the dieldrin sensitivity of the ure2Δ mutant, it did not rescue npr2Δ or npr3Δ (Fig. 3A). Bap2p can also transport isoleucine, valine, and tryptophan (Regenberg et al., 1999), but supplementing YPD medium with these amino acids did not reverse the sensitivity of bap2Δ to dieldrin (Fig. 3B). Deletion of additional amino acid transporter genes (AGP1, BAP3, GAP1, and GNP1) known to facilitate uptake of leucine (Regenberg et al., 1999) or other amino acids did not result in sensitivity to dieldrin (Supplementary fig. 1). To further demonstrate that dieldrin toxicity in yeast was linked to leucine availability, wild-type BY4743 and bap2Δ strains were grown in media containing defined concentrations of leucine. Dieldrin sensitivity was exacerbated at low concentrations of leucine and remediated by increased leucine levels in the media (Figs. 4A and B). The deletion strains utilized in this study were leucine auxotrophs of the BY4743 background that lacks LEU2, the β-isopropylmalate deyhydrogenase responsible for catalyzing the penultimate step in leucine biosynthesis. Restoration of leucine prototrophy through knock-in of the LEU2 gene resulted in resistance to dieldrin at decreased concentrations of leucine (Fig. 5A). Finally, overexpression of Bap2p (the high-affinity leucine permease) or Leu2p (an enzyme involved in leucine biosynthesis) conferred resistance to dieldrin (Figs. 5B and C). Collectively, these data suggest that leucine availability plays a key role in the response to dieldrin.

Fig. 4.

Limiting leucine exacerbates dieldrin sensitivity. Cells were cultured in media containing defined concentrations of leucine. (A) The BY4743 wild-type strain is dependent on leucine for dieldrin tolerance. Growth curves were performed for the indicated doses of dieldrin and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Graphs express AUC as a percentage of untreated wild-type with SE for three independent cultures. Statistical significance between the 2mM leucine AUC and the 0.5, 0.75, and 1mM leucine AUCs was determined by Student’s t-test, where ***p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05. (B) The bap2Δ strain exhibits increased sensitivity to the dieldrin IC25 (690μM) at decreased leucine concentrations. Flow cytometry confirmed altered growth ratios, with data displayed as the mean and SE of three independent cultures. Statistical significance between the corresponding leucine doses in wild-type and bap2Δ was calculated by Student’s t-test, where ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01.

Fig. 5.

Increasing intracellular leucine results in dieldrin resistance. All data shown represent the mean and SE for three independent cultures. (A) Knock-in of the LEU2 gene into BY4743 wild-type increases dieldrin resistance. Cells were cultured in media (SC-LEU) containing defined concentrations of leucine along with the dieldrin IC25 (690μM) and assayed for relative growth to the GFP-expressing BY4743 wild-type strain, which lacks LEU2. Resistance was not seen in YPD media (data not shown). Data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest, where ***p < 0.001, compared with the corresponding leucine dose in wild-type. (B) Wild-type or bap2Δ strains overexpressing Bap2p exhibit increased resistance to dieldrin. Cells harboring empty vector or the HIP FlexGene BAP2 ORF were cultured in SC-LEU media containing 1mM leucine and the dieldrin IC25 (690μM). Relative growth to a wild-type GFP strain was assayed by flow cytometry and statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, where ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01. (C) Overexpression of Leu2p imparts resistance to dieldrin in the Y258 haploid wild-type strain. Growth curve analyses were performed in YPD for dieldrin-treated (IC25: 690μM) Y258 cells overexpressing Leu2p. The area under the curve (AUC) is expressed as a percentage of the untreated strain. Statistical significance was calculated with Student’s t-test, with *p < 0.05.

Dieldrin Inhibits Leucine Uptake and Causes Amino Acid Starvation

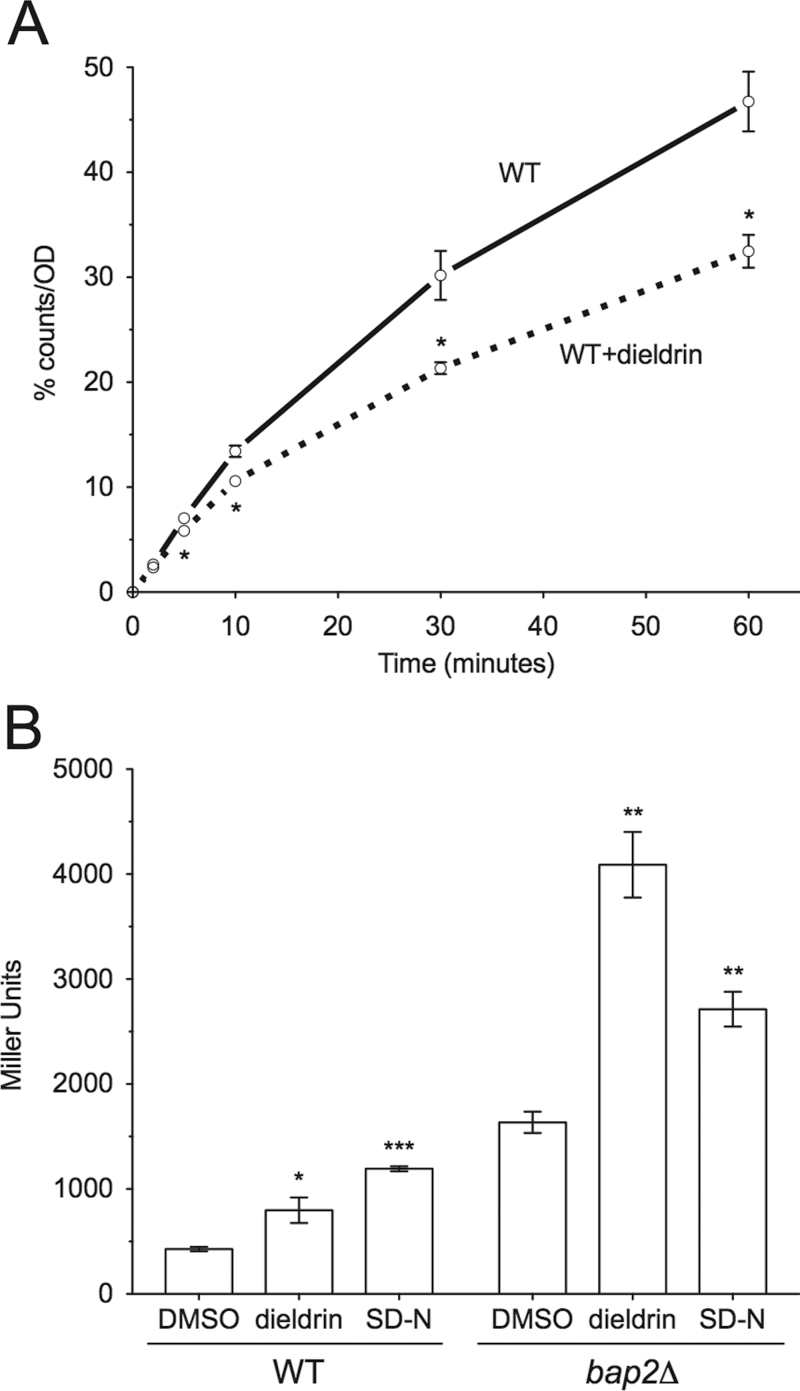

BY4743 strains are leucine auxotrophs dependent on leucine import from the external environment. It was therefore hypothesized that dieldrin did not affect leucine availability by interfering with leucine biosynthesis but instead altered the uptake of leucine from the media. To test this, mid-log phase wild-type cells were incubated with radiolabeled leucine in the presence or absence of the dieldrin IC20 (460μM). Results show that dieldrin significantly inhibited leucine import at various time points as compared with untreated controls (Fig. 6A). With leucine uptake inhibited, it was anticipated that dieldrin would starve the cell for leucine and induce the general control response, a signaling cascade in which increased GCN4 mRNA levels promote transcription of amino acid biosynthetic machinery and permeases (Hinnebusch, 1990). To examine amino acid starvation, a plasmid harboring a GCN4-lacZ fusion gene was transformed into yeast cells and assayed for β-galactosidase activity following dieldrin exposure. As shown in Figure 6B, dieldrin induces β-galactosidase expression from the GCN4-lacZ fusion in both wild-type and bap2Δ cells, demonstrating that amino acid starvation occurs in the presence of dieldrin. Interestingly, although autophagy mutants (which are involved in the starvation response) were identified as sensitive by DSSA at the highest dose of dieldrin, we were unable to confirm growth defects in YPD (after 24 or 48h) or leucine deficient media (Supplementary table 2 and data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Dieldrin inhibits leucine uptake and induces the starvation response. (A) Leucine uptake is inhibited in the presence of dieldrin. Radiolabeled leucine was incubated with yeast cells with or without the dieldrin IC20 (460μM) and uptake was measured by counting radioactivity bound to the filter. Each time point was normalized for cell number and expressed as a percentage of combined total measured radioactivity over the time course for the control. The means and SEs for three independent experiments are shown. Statistical significance between corresponding time points was determined by Student’s t-test, where *p < 0.05. (B) Dieldrin induces amino acid starvation. GCN4-lacZ expression was measured via β-galactosidase activity after treating wild-type or bap2Δ cells with the dieldrin IC20 (460μM) in SC-ura or SD-N media. The means and SEs for two to three independent cultures are shown. Data were analyzed with Student’s t-test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05.

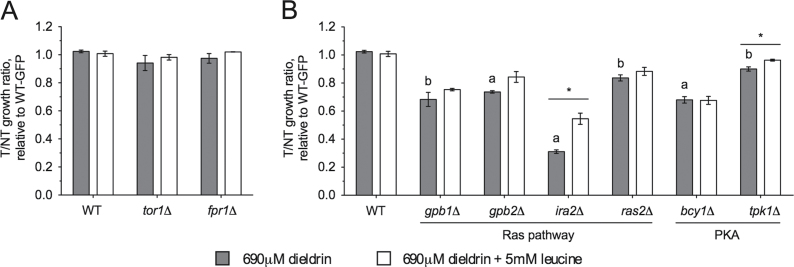

Ras/PKA Signaling, But Not the Target of Rapamycin Pathway, Is Implicated in Dieldrin Toxicity

In S. cerevisiae, the two main nutrient signal transduction pathways are Ras/PKA and target of rapamycin (Tor); signaling through either may be affected during starvation for amino acids such as leucine. Rapamycin inhibits the yeast Tor pathway and induces a nitrogen starvation–like phenotype via formation of a toxic complex with Fpr1p (FKBP12) (Lorenz and Heitman, 1995). We hypothesized that dieldrin was acting similarly to rapamycin, as rapamycin also affects amino acid availability (Beck et al., 1999) and various amino acid signaling mutants sensitive to dieldrin (Fig. 3A) have been confirmed as sensitive to rapamycin (Xie et al., 2005). However, multiple lines of evidence suggest otherwise. Deletion of FPR1 or TOR1 confers resistance or sensitivity, respectively, to rapamycin (Xie et al., 2005) but neither of these mutants was affected by dieldrin (Fig. 7A). Moreover, removal of components downstream of Tor (SIT4, SAP4, SAP155, TIP41, RRD1, and RRD2) and peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases related to Fpr1p (FPR2, FPR3, and FPR4) did not affect growth in dieldrin (Supplementary table 2 and data not shown). In contrast, mutants known to exhibit altered Ras/PKA signaling were sensitive to dieldrin, including those unable to negatively regulate Ras (gpb1Δ, gpb2Δ, and ira2Δ) or PKA (bcy1Δ, deleted for the PKA regulatory subunit), with most unable to be rescued by leucine addition (Fig. 7B). Other mutants (pfk26Δ, fpb26Δ, rmd5Δ, and vid30Δ) lacking genes involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism, a process under the control of PKA, were sensitive to dieldrin (Supplementary fig. 2A), with rmd5Δ displaying leucine-dependent sensitivity to dieldrin (Supplementary fig. 2B). Together, these data show that proper Ras/PKA regulation is required for dieldrin tolerance, but the Tor pathway is not.

Fig. 7.

Altered Ras/PKA, but not Tor signaling, causes dieldrin sensitivity. Relative growth ratios (treatment vs. control) to the GFP-expressing wild-type strain were obtained. All data represent the mean and SE for three independent YPD cultures treated with the dieldrin IC25 (690μM). Statistical significance between dieldrin-treated wild-type and mutant strains were determined with Student’s t-test, where a p < 0.001 and b p < 0.01. Statistical differences between a dieldrin-treated strain versus the same strain treated with dieldrin and leucine are shown as *p < 0.05. (A) Dieldrin does not affect strains lacking components involved in Tor signaling. (B) Strains unable to negatively regulate Ras or PKA are sensitive to dieldrin.

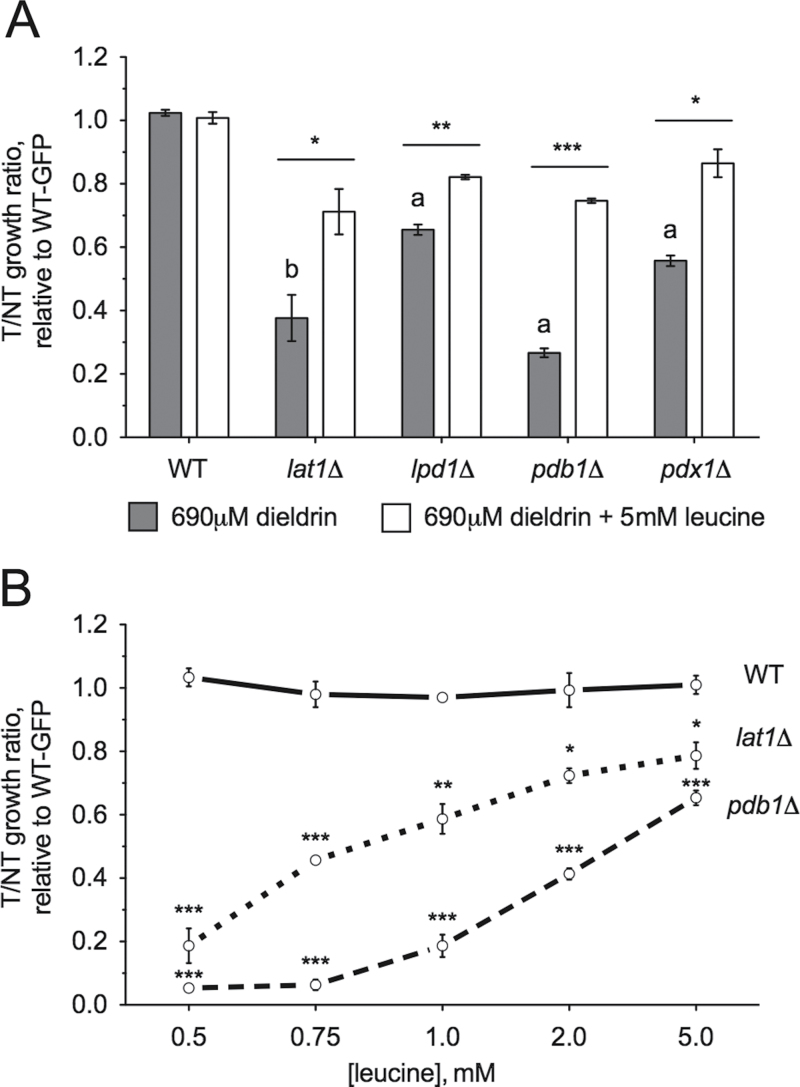

The PDH Complex Is Necessary for Resistance to Dieldrin

The mitochondrially localized PDH complex catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, thus linking glycolysis to the citric acid cycle. Our DSSA and meta-analysis identified four out of the five subunits of PDH (Lpd1p, Lat1p, Pdx1p, and Pdb1, but not Pda1p) as sensitive to dieldrin, which was confirmed by the flow cytometry relative growth assay (Fig. 8A and Supplementary table 2). Surprisingly, exogenous leucine moderately reversed the sensitivity of these mutants to dieldrin. In addition, similar to BY4743 wild-type, bap2Δ, and rmd5Δ (Fig. 4 and Supplementary fig. 2B), the pdb1Δ and lat1Δ PDH mutants were more sensitive to dieldrin when the leucine concentration in the media was decreased (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

The PDH complex is required for dieldrin tolerance. Relative growth ratios (treatment vs. control) to the GFP-expressing wild-type strain were obtained for three independent YPD cultures, for which the means and SEs are shown. Dieldrin was added at a final concentration of 690μM (IC25). (A) Four PDH subunits are necessary for dieldrin resistance in YPD. (B) The lat1Δ and pdb1Δ strains exhibit dieldrin sensitivity that is dependent on leucine concentration. Strains were grown in media containing defined concentrations of leucine and assayed for relative growth to a wild-type GFP strain. Statistical significance between corresponding leucine doses in wild-type and mutant strains was determined by Student’s t-test, where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Dieldrin is a bioaccumulative and persistent pollutant with the potential to cause adverse effects on both the environment and human health (ATSDR, 2002). In this study, we performed a functional screen to identify nonessential yeast deletion mutants experiencing growth defects in dieldrin. Functional profiling of yeast mutants has not been reported for dieldrin or any other environmentally persistent halogenated contaminant. Confirmation of the yeast genes required for dieldrin tolerance, many of which are conserved in humans (Table 3), suggested a mechanism of toxicity—altered leucine availability—that was validated by further experimentation. In yeast, the toxic mechanism of dieldrin is different from that of the toxaphene OCP (Gaytán et al., in preparation). Overlapping GO categories were not identified between our study and gene expression profiles in dieldrin-exposed largemouth bass (Martyniuk et al., 2010), but specific transcriptional responses do not always correlate with genes required for growth under a selective condition (Giaever et al., 2002).

Table 3.

Selected Yeast Genes Required for Dieldrin Tolerance and Their Human Orthologs

| Yeast gene(s)a | Human ortholog | Human protein |

|---|---|---|

| BAP2 | SLC7A1 | Cationic amino acid transport permease |

| BCY1 | PRKAR2A | cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit |

| FBP26/PFK26 | PFKFB1 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase |

| GCN2 | EIF2AK4 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase |

| GPB1/2 | ETEA | Functional ortholog of GPB1/2; inhibits neurofibromin 1 |

| IRA2 | NF1 | Neurofibromin 1, tumor suppressor protein |

| LAT1 | DLAT | Dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase component of PDH complex |

| LPD1 | DLD | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase component of PDH complex |

| NPR2 | NPRL2 | Nitrogen permease regulator-like 2, tumor suppressor candidate |

| PDB1 | PDHB | PDH, E1 component |

| PDX1 | PDHX | Anchors DLD to the DLAT core in the PDH complex |

| RAS2 | KRAS | v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| RMD5 | RMND5A | Required for meiotic nuclear division 5 Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog |

| VID30 | RANBP10 | Ran-binding protein 10 |

aDeletion of any of these genes caused sensitivity to dieldrin (listed in alphabetical order).

Yeast functional genomics, although an invaluable tool in the field of toxicology, is not without its limitations. First, achieving toxicity in yeast often requires high concentrations of xenobiotic; considering the presence of a cell wall and multidrug resistance machinery, this is not surprising. To increase toxicant sensitivity, a strain deleted for important drug resistance transporters could potentially serve as the deletion library background. Dieldrin concentrations used in this study (115–690μM) are higher than those reported as toxic to human cells (25–50μM) (Ledirac et al., 2005). Since the ban of dieldrin, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) describe a steady decrease in mean human blood serum concentrations (maximum 1.4 ppb in the 1976–1980 data); therefore, our results may be most relevant to (1) those with a history of dieldrin exposure; (2) populations living in termiticide-treated homes; and (3) communities consuming fish or other bioaccumulating aquatic species caught adjacent to dieldrin-contaminated hazardous waste sites. Second, although endogenous P450 enzymes can mediate xenobiotic biotransformation in yeast (Käppeli, 1986), differences in metabolism complicate direct comparison with humans. To address these concerns, human S-9 liver microsomes may be added to catalyze toxicant activation. Third, one cannot identify target organs or adverse systemic effects, such as perturbations of the endocrine, immune, or circulatory systems. The discovery of nonobvious equivalent mutant phenotypes between different species (i.e., orthologous phenotypes) may prove useful in this arena. For example, McGary et al. (2010) identified five genes shared between studies examining yeast deletion strain sensitivity to the hypercholesterolemia drug lovastatin and abnormal angiogenesis in mutant mice, suggesting that despite the lack of blood vessels, yeast can model the genetics of mammalian vasculature formation. Similar analyses of yeast functional toxicogenomics data, although not performed within this study, may reveal potential mechanisms of action related to more complex biological processes not present in yeast.

Compounds other than dieldrin alter amino acid availability in yeast, including the immunosuppressant drugs rapamycin (Beck et al., 1999), FK506 (Heitman et al., 1993), and FTY720 (Welsch et al., 2003), the antimalarial drug quinine (Khozoie et al., 2009), the anesthetic isoflurane (Palmer et al., 2002), and the orphan drug phenylbutyrate (Grzanowski et al., 2002). The chemical structure of dieldrin does not exhibit similarity to any of these compounds. Portions of our data suggested that the mechanism of action for dieldrin is similar to rapamycin, but removal of the rapamycin targets Fpr1p or Tor1p, which results in rapamycin resistance and sensitivity, respectively, does not affect growth in the presence of dieldrin (Fig. 7A). FK506 and FTY720 inhibit uptake of leucine and tryptophan (Heitman et al., 1993; Welsch et al., 2003); however, a mutant lacking TAT2, a high-affinity tryptophan and tyrosine permease, was not sensitive to dieldrin (Supplementary fig. 1). Moreover, inhibition of amino acid uptake is dependent upon a 4–5h preincubation of yeast cells with FK506 or FTY720, indicating that time is needed for the drug’s effects, possibly because transporter folding, assembly, or transport is altered. In contrast, dieldrin inhibited amino acid uptake without preincubation, a result similar to that for the antimalarial drug quinine, which competitively inhibits tryptophan uptake via the Tat2p permease (Khozoie et al., 2009). Further studies are needed to determine if dieldrin inhibits amino acid transport by binding directly to a leucine permease.

Although our results do not indicate that dieldrin’s toxic mechanism in yeast is conserved to humans, studies have demonstrated that dieldrin and other OCPs can alter availability of amino acids or their derivatives in mammalian systems. An oral dose of dieldrin to rhesus monkeys depressed leucine uptake in the intestine (Mahmood et al., 1981), whereas a series of ip injections of lindane, a related OCP, decreased leucine transport in chicken enterocytes (Moreno et al., 1994). Leucine uptake was decreased in rat intestine after a single oral dose to endosulfan, another OCP (Wali et al., 1982). Of greater concern is the potential for dieldrin, a known neurotoxicant linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, to affect the levels of amino acids or their derivatives in the brain. Several neurotransmitters are amino acids (glutamate, aspartate, and glycine) or amino acid derivatives (tryptophan is the precursor for serotonin, tyrosine for dopamine, and glutamate for GABA). Leucine is neither a neurotransmitter nor a precursor, but it furnishes α-NH2 groups for glutamate synthesis via the branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase, thus playing a major role in regulating cellular pools of the glutamate neurotransmitter (Yudkoff et al., 1994). Further experimentation is necessary to determine whether dieldrin inhibits leucine uptake in human cells or more complex organisms.

Genes encoding proteins that negatively regulate Ras (the GPB1/GPB2 paralogs and IRA2) or PKA (BCY1) are required for dieldrin tolerance (Fig. 7B). Combined with evidence that gpb1Δgpb2Δ ira2Δ and bcy1Δ strains are intolerant to nitrogen starvation (Harashima and Heitman, 2002; Tanaka et al., 1990), these data are consistent with dieldrin’s ability to decrease leucine (nitrogen) availability (Fig. 6A) and induce nitrogen starvation via Gcn4p (Fig. 6B). Double GPB1/2 as well as single IRA2 or BCY1 deletion mutants also display phenotypes consistent with hyperactive Ras or PKA (Harashima and Heitman, 2002), phenomena linked to cancer in humans. A constitutively active Ras2Val19 protein reduces the response of leucine transport to a poor nitrogen source (Sáenz et al., 1997), but experiments with a Ras2Val19 allele did not alter sensitivity to dieldrin (data not shown). Dieldrin has tumor-promoting properties in rodents (ATSDR, 2002), possibly via inhibition of intracellular gap junction channels (Matesic et al., 2001). Chaetoglobosin K, a compound with Ras tumor suppressor activity, alleviates dieldrin inhibition of gap junction channels (Matesic et al., 2001). Dieldrin also affects signaling downstream of Ras, increasing phosphorylated Raf, MEK1/2, and ERK1/2 in human keratinocytes (Ledirac et al., 2005). Human homologs of the Ras/PKA signaling genes required for dieldrin resistance in yeast are posited tumor suppressors, including the IRA2 homolog neurofibromin 1 and the GPB1/2 functional ortholog ETEA (Phan et al., 2010). If our data are validated in higher organisms, it may suggest that an individual with altered Ras/PKA signaling is more susceptible to dieldrin.

Components of the highly conserved mitochondrial PDH complex were also identified as necessary for dieldrin tolerance (Fig. 8 and Table 3). PDH links glycolysis to the citric acid cycle by catalyzing the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA (reviewed in Pronk et al., 1996). Leucine modestly reversed the sensitivity of PDH mutants to dieldrin, indicating that leucine is necessary for or a product of a PDH-mediated process needed for dieldrin tolerance. Except for LAT1, all PDH genes contain putative recognition sites for the master regulator of the amino acid starvation response, GCN4 (Wenzel et al., 1992), with LPD1 under the control of Gcn4p during amino acid starvation (Zaman et al., 1999). This suggests that PDH is involved in the starvation response, which we show is induced by dieldrin (Fig. 6B). In addition, the pda1Δ strain demonstrates a partial leucine requirement for growth (Wenzel et al., 1992). Reduced PDH activity has been associated with various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases (Sorbi et al., 1983), and mice deficient in dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD—the LPD1 homolog) show increased vulnerability to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), a dopaminergic neurotoxicant used as a model for Parkinson’s disease (Klivenyi et al., 2004).

We hypothesize a simple model connecting leucine uptake, Ras/PKA signaling, and PDH. Our results suggest that dieldrin likely affects leucine uptake at the amino acid transporter level. Leucine auxotrophs, along with strains lacking leucine transporters or requisite amino acid signaling, cannot adequately cope with the resulting leucine starvation and therefore experience growth defects in dieldrin. Leucine starvation caused by dieldrin would also be detrimental to strains unable to negatively regulate Ras/PKA, as activation of this signaling pathway promotes cell growth, a cellular process incompatible with the starvation response. Finally, the sensitivity of PDH mutants may be explained by their inability to activate starvation pathways essential for the response to dieldrin-induced leucine depletion. Our results underscore the value of functional profiling in yeast and provide data useful for further gene or pathway-specific studies.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program (P42ES004705 to C.D.V., 3P42ES004705-22S1 to N.D.D. and C.D.V.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIEHS or NIH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Aaron Welch of the Koshland laboratory (University of California, Berkeley) for the BAP2 HIP FlexGene, Alan Hinnebusch (National Institutes of Health) for the B180 plasmid (GCN4-lacZ), Akemi Kunibe of the Drubin-Barnes laboratory (University of California, Berkeley) for the pRS305 plasmid and technical advice on the LEU2 knock-in, and Vanessa De La Rosa and Tami Swenson for critical reading of the manuscript. B.D.G. is a trainee in the Superfund Research Program (University of California, Berkeley).

REFERENCES

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) (2002). Toxicological Profile for Aldrin/Dieldrin. US Dept of Health and Human Services, ATSDR, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- Beck T., Schmidt A., Hall M. N. (1999). Starvation induces vacuolar targeting and degradation of the tryptophan permease in yeast. J. Cell Biol 146, 1227–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos S. C., Teixeira M. C., Cabrito T. R., Sá-Correia I. (2012). Yeast toxicogenomics: Genome-wide responses to chemical stresses with impact in environmental health, pharmacology, and biotechnology. Front. Genet 3, 63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G., Chu A. M., Ni L., Connelly C., Riles L., Véronneau S., Dow S., Lucau-Danila A., Anderson K., André B., et al. (2002). Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418, 387–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanowski A., Needleman R., Brusilow W. S. (2002). Immunosuppressant-like effects of phenylbutyrate on growth inhibition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet 41, 142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima T., Heitman J. (2002). The Gα protein Gpa2 controls yeast differentiation by interacting with kelch repeat proteins that mimic Gβ subunits. Mol. Cell 10, 163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman J., Koller A., Kunz J., Henriquez R., Schmidt A., Movva N. R., Hall M. N. (1993). The immunosuppressant FK506 inhibits amino acid import in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol 13, 5010–5019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch A. G. (1990). Involvement of an initiation factor and protein phosphorylation in translational control of GCN4 mRNA. Trends Biochem. Sci 15, 148–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo W. J., Loguinov A., Wintz H., Chang M., Smith A. H., Kalman D., Zhang L., Smith M. T., Vulpe C. D. (2009a). Comparative functional genomic analysis identifies distinct and overlapping sets of genes required for resistance to monomethylarsonous acid (MMAIII) and arsenite (AsIII) in yeast. Toxicol. Sci 111, 424–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo W. J., Ren X., Chu F., Aleshin M., Wintz H., Burlingame A., Smith M. T., Vulpe C. D., Zhang L. (2009b). Acetylated H4K16 by MYST1 protects UROtsa cells from arsenic toxicity and is decreased following chronic arsenic exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 241, 294–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson J. L. (2001). Aldrin and dieldrin: A review of research on their production, environmental deposition and fate, bioaccumulation, toxicology, and epidemiology in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect 109(Suppl. 1), 113–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käppeli O. (1986). Cytochromes P-450 of yeasts. Microbiol. Rev 50, 244–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khozoie C., Pleass R. J., Avery S. V. (2009). The antimalarial drug quinine disrupts Tat2p-mediated tryptophan transport and causes tryptophan starvation. J. Biol. Chem 284, 17968–17974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klivenyi P., Starkov A. A., Calingasan N. Y., Gardian G., Browne S. E., Yang L., Bubber P., Gibson G. E., Patel M. S., Beal M. F. (2004). Mice deficient in dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase show increased vulnerability to MPTP, malonate and 3-nitropropionic acid neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem 88, 1352–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledirac N., Antherieu S., d’Uby A. D., Caron J. C., Rahmani R. (2005). Effects of organochlorine insecticides on MAP kinase pathways in human HaCaT keratinocytes: Key role of reactive oxygen species. Toxicol. Sci 86, 444–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz M. C., Heitman J. (1995). TOR mutations confer rapamycin resistance by preventing interaction with FKBP12-rapamycin. J. Biol. Chem 270, 27531–27537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A., Agarwal N., Sanyal S., Dudeja P. K., Subrahmanyam D. (1981). Acute dieldrin toxicity: Effect on the uptake of glucose and leucine and on brush border enzymes in monkey intestine. Chem. Biol. Interact 37, 165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk C. J., Kroll K. J., Doperalski N. J., Barber D. S., Denslow N. D. (2010). Genomic and proteomic responses to environmentally relevant exposures to dieldrin: Indicators of neurodegeneration?. Toxicol. Sci 117, 190–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matesic D. F., Blommel M. L., Sunman J. A., Cutler S. J., Cutler H. G. (2001). Prevention of organochlorine-induced inhibition of gap junctional communication by chaetoglobosin K in astrocytes. Cell Biol. Toxicol 17, 395–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGary K. L., Park T. J., Woods J. O., Cha H. J., Wallingford J. B., Marcotte E. M. (2010). Systematic discovery of nonobvious human disease models through orthologous phenotypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A 107, 6544–6549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. J., Pellicer S., Marti A., Arenas J. C., Fernández-Otero M. P. (1994). Effect of lindane on galactose and leucine transport in chicken enterocytes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol 109, 159–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North M., Steffen J., Loguinov A. V., Zimmerman G. R., Vulpe C. D., Eide D. J. (2012). Genome-wide functional profiling identifies genes and processes important for zinc-limited growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 8, e1002699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North M., Tandon V. J., Thomas R., Loguinov A., Gerlovina I., Hubbard A. E., Zhang L., Smith M. T., Vulpe C. D. (2011). Genome-wide functional profiling reveals genes required for tolerance to benzene metabolites in yeast. PLoS ONE 6, e24205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer L. K., Wolfe D., Keeley J. L., Keil R. L. (2002). Volatile anesthetics affect nutrient availability in yeast. Genetics 161, 563–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan V. T., Ding V. W., Li F., Chalkley R. J., Burlingame A., McCormick F. (2010). The RasGAP proteins Ira2 and neurofibromin are negatively regulated by Gpb1 in yeast and ETEA in humans. Mol. Cell Biol 30, 2264–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk J. T., Yde Steensma H., Van Dijken J. P. (1996). Pyruvate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 12, 1607–1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenberg B., Düring-Olsen L., Kielland-Brandt M. C., Holmberg S. (1999). Substrate specificity and gene expression of the amino-acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet 36, 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. R., Caudle W. M., Wang M., Dean E. D., Pennell K. D., Miller G. W. (2006). Developmental exposure to the pesticide dieldrin alters the dopamine system and increases neurotoxicity in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J 20, 1695–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz D. A., Chianelli M. S., Stella C. A., Mattoon J. R., Ramos E. H. (1997). RAS2/PKA pathway activity is involved in the nitrogen regulation of L-leucine uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 29, 505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Chhillar N., Banerjee B., Bala K., Basu M., Mustafa M. (2013). Organochlorine pesticide levels and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in north Indian population. Hum. Exp. Toxicol 32, 24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbi S., Bird E. D., Blass J. P. (1983). Decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in Huntington and Alzheimer brain. Ann. Neurol 13, 72–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz L. M., Scharfe C., Deutschbauer A. M., Mokranjac D., Herman Z. S., Jones T., Chu A. M., Giaever G., Prokisch H., Oefner P. J., et al. (2002). Systematic screen for human disease genes in yeast. Nat. Genet 31, 400–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Nakafuku M., Satoh T., Marshall M. S., Gibbs J. B., Matsumoto K., Kaziro Y., Toh-e A. (1990). S. cerevisiae genes IRA1 and IRA2 encode proteins that may be functionally equivalent to mammalian ras GTPase activating protein. Cell 60, 803–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wali R. K., Singh R., Dudeja P. K., Mahmood A. (1982). Effect of a single oral dose of endosulfan on intestinal uptake of nutrients and on brush-border enzymes in rats. Toxicol. Lett 12, 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf M. G., Knekt P., O’Reilly E. J., Lyytinen J., Reunanen A., Laden F., Altshul L., Ascherio A. (2010). Persistent organochlorine pesticides in serum and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 74, 1055–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch C. A., Hagiwara S., Goetschy J. F., Movva N. R. (2003). Ubiquitin pathway proteins influence the mechanism of action of the novel immunosuppressive drug FTY720 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem 278, 26976–26982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel T. J., van den Berg M. A., Visser W., van den Berg J. A., Steensma H. Y. (1992). Characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants lacking the E1 alpha subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Eur. J. Biochem 209, 697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M. W., Jin F., Hwang H., Hwang S., Anand V., Duncan M. C., Huang J. (2005). Insights into TOR function and rapamycin response: Chemical genomic profiling by using a high-density cell array method. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 7215–7220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff M., Daikhin Y., Lin Z. P., Nissim I., Stern J., Pleasure D., Nissim I. (1994). Interrelationships of leucine and glutamate metabolism in cultured astrocytes. J. Neurochem 62, 1192–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman Z., Bowman S. B., Kornfeld G. D., Brown A. J., Dawes I. W. (1999). Transcription factor GCN4 for control of amino acid biosynthesis also regulates the expression of the gene for lipoamide dehydrogenase. Biochem. J 340,(Pt 3) 855–862 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.