Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate refractive state in children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO).

Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study includes consecutive children with unilateral congenital NLDO. Examination under anesthesia was performed to perform cycloplegic refraction and was followed by appropriate intervention in each patient. Refractive errors of the involved and sound fellow eyes were compared.

Results

Ninety-four children with mean age of 25.4±20.4 months (range, 6 months to 10 years) were enrolled from May 2007 to January 2010. Based on spherical equivalent refractive error, hyperopia was more common in the affected eyes, however this difference failed to reach statistical significance (P=0.5). Anisometropia more and less than 0.5 diopters (D) was present in 25% and 43% of patients respectively. Interocular difference was significant in terms of spherical refractive error and spherical equivalent (P=0.003) but not cylindrical refractive error. When the comparison was limited to hyperopic eyes, the interocular difference became more significant in terms of spherical refractive error and spherical equivalent (P<0.001). Each month of increase in age was associated with an interocular difference of 0.007D in spherical refractive error (r=0.242, P=0.02). Older age at the time of intervention was associated with more procedures (r=0.297, P=0.004).

Conclusion

Unilateral congenital NLDO is associated with anisometropia especially anisohyperopia which may predispose affected children to amblyopia. With increasing age, the degree of anisometropia and the number of required procedures increase. It is prudent to perform refraction and initiate proper intervention at a younger age.

Keywords: Amblyopia, Anisometropia, Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction, Refraction

INTRODUCTION

Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) is most commonly due to obstruction at the level of Hasner membrane and becomes symptomatic in 5-6% of infants.1,2 Although 90% of such obstructions resolve spontaneously before the age of one year, continuous presence of an abundant tear meniscus and mucopurulent discharge over the cornea during the most critical period of visual maturation may be a potential cause of amblyopia, yet some authors do not endorse this assumption.3,4

The importance of anisometropia as a cause of amblyopia has been well recognized.5-10 Development of stereoacuity is related to similarity in the refractive state of the fellow eyes, furthermore fine motor skills which require speed and precision of movements, are defective in amblyopic children.11,12

Some retrospective reports have confirmed a higher prevalence of anisometropia and amblyopia in patients with congenital NLDO.3,13-15 In the current study, we prospectively evaluated the correlation between congenital NLDO and anisometropia.

METHODS

The current study includes all children with unilateral congenital NLDO who were referred to our center from May 2007 to January 2010 and scheduled for intervention. The study was approved by the Scientific and Ethics Committee of the Ophthalmic Research Center and written informed consent was obtained from all guardians prior to enrollment.

Inclusion criteria were onset of epiphora and/or discharge from birth which did not respond to lacrimal sac massage until one year of age when the epiphora was clear, and up to the age of 6 months when there was mucopurulent discharge. Other inclusion criteria were unilateral involvement from the beginning and no history of surgery. We did not limit patient age when the disease had been confirmed to have started from birth. Exclusion criteria consisted of any other extra- or intraocular abnormalities which may affect refractive state such as blepharoptosis, strabismus, microphthalmia and cataract.

Cyclopentolate 1% drops were instilled twice in each eye, 5 minutes apart and 30 minutes before the patient underwent examination under anesthesia (EUA). Due to the presence of epiphora and/or discharge, it was not possible to mask the examiner.

EUA started with intraocular pressure measurement followed by cycloplegic refraction and finally anterior and posterior segments examinations. Afterwards, surgical intervention was performed which included nasolacrimal duct probing as the initial procedure; repeat probing with inferior turbinate fracture, silicone intubation and dacryocystorhinostomy were employed sequentially in unresponsive cases. In cases requiring more than one procedure, findings at the time of initial surgery were considered for the purpose of the study.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0, SPSS Co., Chicago, IL, USA) and data were evaluated utilizing Chi-Square, paired t, regression analysis, McNemar and Spearman’s correlation tests when appropriate.

RESULTS

Ninety-four patients with mean age of 25.4±20.4 months (range, 6 months to 10 years) were enrolled in the study. The left eye was involved in 51 (54.3%) patients and 54 subjects (57.5%) were female.

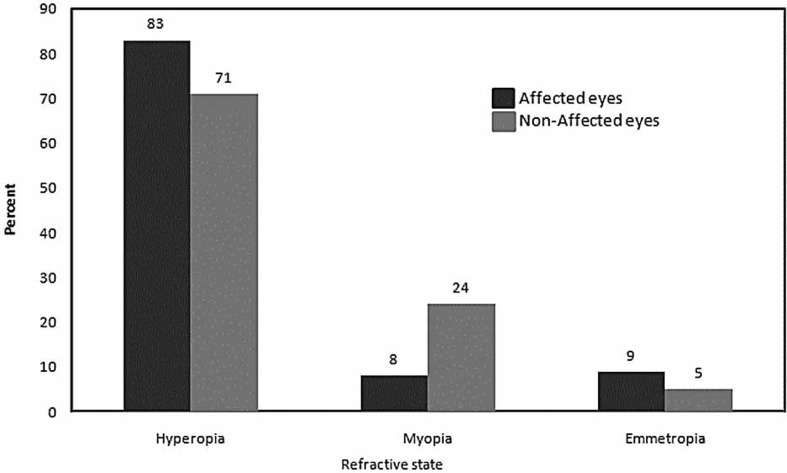

Based on spherical equivalent refractive error, hyperopia was more common in affected eyes while myopia was more prevalent in non-affected fellow eyes (P=0.5, McNemar test, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of different types of refractive state in affected and non-affected fellow eyes.

Affected eyes and non-affected fellow eyes were significantly different in terms of spherical refractive error (P=0.003, paired t-test) and spherical equivalent (P=0.003, paired t-test), but not cylindrical refractive error (P=0.2), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Difference between affected and non-affected fellow eyes in mean values of refractive indices

| Mean value(affected eye) | Mean value(fellow eye) | Difference | 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Sphere (D) | 1.29±0.97 | 1.10±0.73 | 0.20±0.6 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.003 |

| Cylinder(D) | -0.81±.92 | -0.71±0.81 | -0.11±0.8 | -0.27 | 0.063 | 0.2 |

| Axis(degree) | 101±85.8 | 92±87.2 | 9±63 | -3.9 | 21.9 | 0.2 |

| SE (D) | 1.13±0.86 | 0.91±0.62 | 0.22±0.67 | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.003 |

D, diopter; CI, confidence interval; SE, spherical equivalent

After classifying affected eyes as hyperopic, myopic and emmetropic, the interocular difference was significant in terms of spherical refractive error (P<0.001, Paired t-test) and spherical equivalent (P<0.001, Paired t-test) in hyperopic eyes, however this was not the case in myopic or emmetropic eyes (all P values>0.1).

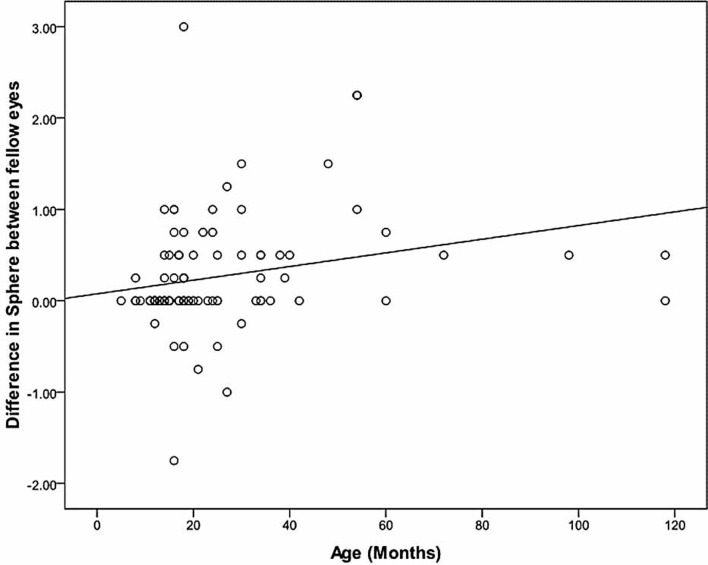

Each month of increase in age was associated with a significant increase of 0.007D in interocular difference in spherical refractive error (r=0.242, regression analysis, P=0.02, Fig. 2). The age-dependent variation was not significant for cylindrical refractive error (r=-0.110, P=0.3,) and spherical equivalent (r=0.154, P=0.1).

Figure 2.

Correlation between age and interocular difference in spherical refractive error.

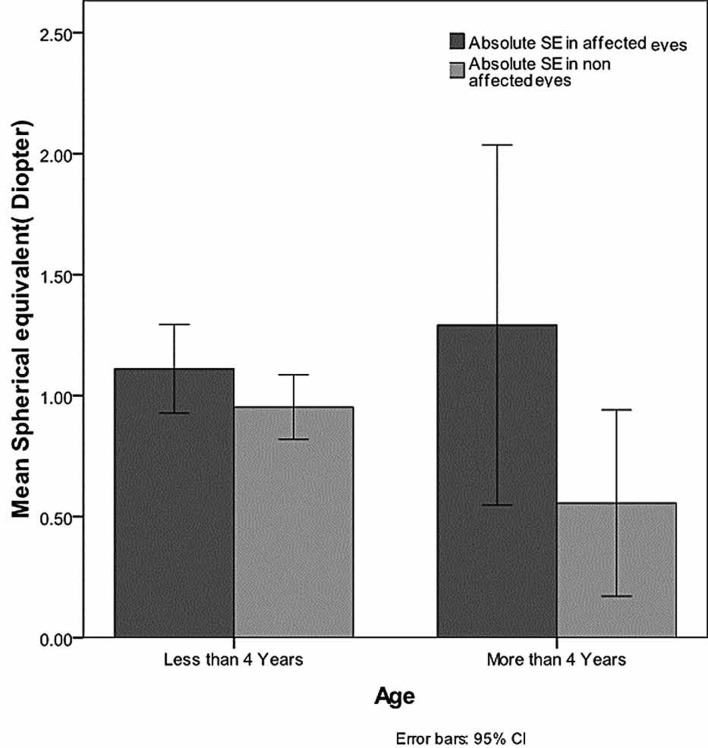

After stratifying the patients into two age groups, the interocular difference in spherical equivalent was more significant in subjects older than 4 years as compared to those less than 4 years of age (P=0.02 and P=0.03 respectively, paired t-test, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Interocular difference in spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error before and after the age of 4 years.

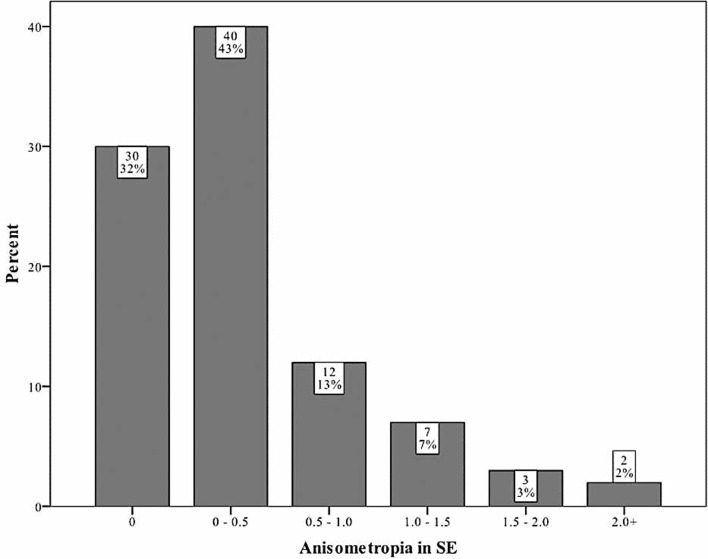

Spherical equivalent anisometropia was greater than 0.5D in 25% of cases and exceeded 1D in 12% (Fig. 4). Cylindrical anisometropia more than 0.5D was present in 8.5% and that exceeding 1D was observed in only 2.3% of subjects.

Figure 4.

Frequency of different amounts of anisometropia based on spherical equivalent (SE).

In our stepwise approach, success rate for first-time surgery was 78% and reached 93% and 99% after the second and third procedures, respectively; only one case required 4 operations.

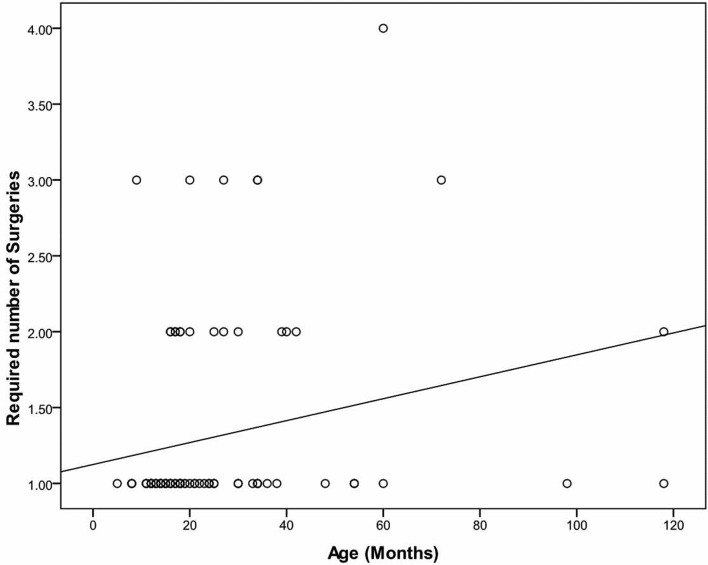

Increasing patient age was significantly associated with a larger number of interventions (r=0.297, P=0.004, Spearman correlation, Fig. 5). Patients referred before the age of 2 years required a mean of 1.2±0.5 procedures while those referred after 2 years of age needed 1.6±0.8 operations for relief of symptoms (P=0.006, regression analysis).

Figure 5.

Correlation between age and number of procedures required to relieve the obstruction.

DISCUSSION

Congenital NLDO is a common childhood disorder which usually improves spontaneously during the first year of life; however its effect on refractive status and any correlation with amblyopia have been controversial.3,4,13-15

Chalmers and Griffiths studied 130 children with unilateral congenital NLDO and compared fellow eyes from a refractive standpoint; all subjects were hyperopic in the affected eye and five suffered from amblyopia.13 In another study by Lacey et al, 50 patients who had undergone probing 15 years earlier22 were recalled and compared with a sex- and age-matched group. Affected subjects were reported to have a higher rate of amblyopia in the eye with history of congenital NLDO.3 More recently and in retrospective case reports, Simon et al14 showed anisometropic amblyopia in 5 subjects with unilateral congenital NLDO and Matta et al15 reported that children with congenital NLDO seem to be at higher risk of amblyopia. Both studies did not report any anisometropic patient with NLDO in the better eye.14,15

It is well established that anisometropia is an important amblyogenic factor.8-10 This may be more significant when the interocular difference exceeds one diopter.16-18 Due to individual physiologic differences, one cannot define an exact cutoff value for anisometropia, hence amblyopia may even be seen with milder degrees of anisometropia.5,6,9,19 In contrast to strabismic and deprivational amblyopia, anisometropic amblyopia is more frequently asymptomatic and diagnosed at an older age such that only 15% of affected subjects are diagnosed before the age of 5 years.20 Anisometropia may also disturb binocularity as reflected by lower levels of stereoacuity.11,21 Accordingly, treatment is more difficult and time consuming.17 Studies on anisometropic amblyopia have shown that the most important factors in predicting the response to treatment are age and depth of amblyopia which are strictly related to the severity of anisometropia.10,22-25 One study demonstrated that in anisometropic subjects, amblyopia is less severe before 3 years of age and improvement is more probable.17

Our study demonstrated that increasing age in patients with unilateral congenital NLDO was associated with a higher prevalence and severity of anisometropia. We also observed that differences between affected and sound eyes were significant in terms of spherical refractive error and spherical equivalent, and that hyperopia was more common in affected eyes; these factors may predispose patients with congenital NLDO to hyperopic anisometropia. The current series also showed that in patients aged 4 years or older, interocular difference between spherical refractive error and spherical equivalent was more significant as compared to subjects younger than 4 years. The importance of this finding is that amblyopia therapy is much more difficult in older children.22-24

The above mentioned findings show that when unilateral congenital NLDO becomes persistent, the probability and severity of hyperopia increases, predisposing the affected eye to a higher chance of amblyopia.26-28

As previously mentioned, the depth of amblyopia is related to the severity of anisometropia, especially in hyperopic patients in whom a less favorable response to treatment is seen as compared to myopic patients.26-28

We observed that when treatment is initiated at an older age, significantly more interventions are necessary to relieve the NLDO. We may thus conclude that older subjects, who are at higher risk of amblyopia, are also prone to reduced success; this may lead to a vicious cycle implying another benefit for early intervention.

It has been reported that even after improvement of lacrimal obstruction, anisometropic hyperopia is more common in patients with a history of unilateral congenital NLDO14 and therefore refraction should be rechecked at regular intervals even after anatomical and physiological improvement.

One limitation of the current study was that we had no access to refractive status of our study population at an earlier age and therefore could not prove that the anisometropia was actually the result of NLDO. Another weakness of our study was that we could not mask the examiner performing the refractions and that due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we could not determine whether anisometropia persists at an older age or whether it actually leads to amblyopia. Atilla et al have demonstrated emmetropization in anisometropic patients despite persisting anisometropia.29 It is unclear from our study that if NLDO is relieved, these patients will have the chance to achieve emmetropia and whether anisometropia decreases or not.

In conclusion, unilateral congenital NLDO may be a risk factor for aniso-hypermetropia and treatment should probably not be delayed. Future studies are warranted to elucidate whether treatment in unilateral congenital NLDO is more important and should be initiated earlier than bilateral cases.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simon JW. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 6th ed. San Francisco: LEO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kersten RC. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Bosniak ed. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacey BA, McGinnity GF, Johnston PB, Archer DB. Congenital epiphora as a potential cause of amblyopia. Vision Res. 1995;35:130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis JD, MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Can congenital nasolacrimal-duct obstruction interfere with visual development? A cohort case control study. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;35:81–85. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19980301-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helveston EM. Relationship between degree of anisometropia and depth of amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966;62:757–759. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(66)92207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik SR, Gupta AK, Choudhry S. Anisometropia- its relation to amblyopia and eccentric fixation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1968;52:773–776. doi: 10.1136/bjo.52.10.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutschke PJ, Scott WE, Keech RV. Anisometropic amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:258–263. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen DK. Anisometropic amblyopia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1980;17:180–184. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19800501-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townshend AM, Holmes JM, Evans LS. Depth of anisometropic amblyopia and difference in refraction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caputo R, Frosini R, De Libero C, Campa L, Magro EF, Secci J. Factors influencing severity of and recovery from anisometropic amblyopia. Strabismus. 2007;15:209–214. doi: 10.1080/09273970701669983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobson V, Miller JM, Clifford-Donaldson CE, Harvey EM. Associations between anisometropia, amblyopia, and reduced stereoacuity in a school-aged population with a high prevalence of astigmatism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4427–4436. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webber AL, Wood JM, Gole GA, Brown B. The effect of amblyopia on fine motor skills in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:594–603. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalmers RJ, Griffiths PG. Is congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction a risk factor for the development of amblyopia? British Orthoptic Journal. 1996;53:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon JW, Ngo Y, Ahn E, Khachikian S. Anisometropic amblyopia and nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009;46:182–183. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20090505-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matta NS, Singman EL, Silbert DI. Prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2010;14:386–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue SP. The relationship between anisometropia, patient age, and the development of amblyopia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:313–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donahue SP. Relationship between anisometropia, patient age, and the development of amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb CJ, Russell K, Cox A, MacEwen CJ. Factors influencing visual outcome in anisometropic amblyopes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1278–1281. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.11.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milder B, Rubin ML. The fine art of prescribing glasses. 2nd ed. Florida: Triad publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw DE, Fielder AR, Minshull C, Rosenthal AR. Amblyopia-factors influencing age of presentation. Lancet. 1988;2:207–209. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weakley DR. The association between nonstrabismic anisometropia, amblyopia, and subnormal binocularity. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn JT, Schiffman J, Feuer W, Corona A. The therapy of amblyopia: an analysis of the results of amblyopia therapy utilizing the pooled data of published studies. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1998;96:431–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn JT, Woodruff G, Thompson JR, Hiscox F, Feuer W, Schiffman J, et al. The therapy of amblyopia: an analysis comparing the results of amblyopia therapy utilizing two pooled data sets. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:373–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussein MA, Coats DK, Muthialu A, Cohen E, Paysse EA. Risk factors for treatment failure of anisometropic amblyopia. J AAPOS. 2004;8:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaka-Ur-Rab S. Evaluation of relationship of ocular parameters and depth of anisometropic amblyopia with the degree of anisometropia. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:99–103. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.25830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chekitaan, Karthikeyan B, Meenakshi S. The results of treatment of anisomyopic and anisohypermetropic amblyopia. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:231–237. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weakley DR. The association between anisometropia, amblyopia, and binocularity in the absence of strabismus. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:987–1021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutstein RP, Corliss D. Relationship between anisometropia, amblyopia, and binocularity. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:229–233. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199904000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atilla H, Kaya E, Erkam N. Emmetropization in anisometropic amblyopia. Strabismus. 2009;17:16–19. doi: 10.1080/09273970802678057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]