Abstract

PURPOSE

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS) is a rare hereditary cancer syndrome associated with germline mutations in the TP53 gene. While sarcomas, brain tumors, leukemias, breast and adrenal cortical carcinomas are typically recognized as LFS- associated tumors, the occurrence of gastrointestinal neoplasms has not been fully evaluated. In this analysis, we investigated the frequency and characteristics of gastric cancer (GC) in LFS.

METHODS

Pedigrees and medical records of 62 TP53 mutation-positive families were retrospectively reviewed from the Dana-Farber/National Cancer Institute LFS registry. We identified subjects with GC documented either by pathology report or death certificate, and performed pathology review of the available specimens.

RESULTS

Among 62 TP53 mutation-positive families, there were 429 cancer-affected individuals. GC was the diagnosis in the lineages of 21 (4.9%) subjects from 14 families (22.6%). The mean and median ages at GC diagnosis were 43 and 36 years, respectively (range 24-74 years), significantly younger compared to the median age at diagnosis in the general population based on SEER data (71 years). Five (8.1%) families reported 2 or more cases of GC and 6 (9.7%) families had cases of both colorectal and gastric cancers. No association was seen between phenotype and type/location of the TP53 mutations. Pathology review of the available tumors revealed both intestinal and diffuse histologies.

CONCLUSIONS

Early-onset GC appears to be a component of LFS, suggesting the need for early and regular endoscopic screening in individuals with germline TP53 mutations, particularly among those with a family history of GC.

Keywords: Li Fraumeni syndrome, gastric cancer, hereditary gastric cancer syndromes, germline mutations, TP53

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide and a leading cause of cancer-related mortality. In 2010, it is estimated that 21,000 new cases of gastric cancer were diagnosed in the United States alone and approximately 50% of affected individuals died from the disease1. Although the majority of gastric cancers are sporadic, about 10% are familial2, 3. Among the latter group, germline mutations in the CDH1 gene account for 30-40% of the rare syndrome known as Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancers (HDGC)4-8. Gastric cancers also occur, but less frequently, as a component of other hereditary cancer syndromes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gastric cancer in hereditary cancer syndromes.

| Syndromes | Gene Involved | Gastric Cancer Risk | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer | CDH1 | 67%-83% | Pharoa et al39 |

| Syndrome (HDGC) | Kaurah et al8 | ||

| Hereditary Non Polyposis Colorectal | MLH1, MSH2, | 2%-30% . | Koornstra et al40 |

| Cancer (HNPCC) | MSH6, PMS2 | ||

| Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (PJS) | STK11 | 29% | van Lier et al 41 |

| Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer | BRCA1 | 5.5% | Thompson et al42 Brose et al43 |

| Syndrome (HBOC) | BRCA2 | 2.6% | Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium44 Easton et al45 |

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) | APC | 2.1%-4.2%* | Park et al46 Iwama et al47 |

| Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome (JPS)^ | SMAD4, BMPR1A | N/A | - |

| Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS)^ | TP53 | N/A | - |

This increased risk is for the Korean and Japanese populations. In other ethnicities the risk is the same as the general population.

The estimate of the gastric cancer risk has not been calculated for these conditions

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS) is a rare autosomal dominant hereditary cancer syndrome associated with germline mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene9. Sarcomas of soft tissue and bone, brain tumors, leukemias, breast and adrenal cortical carcinomas are classically included in the LFS tumor spectrum10, 11. Additional studies have shown that individuals with germline TP53 mutations have an increased risk of a broad range of neoplasms, including carcinomas of the lung, gonadal germ cell tumors, melanomas and lymphomas12-20.

Our group has previously shown that the prevalence of early-onset (age <50 years) colorectal cancer is increased in LFS families21. This finding led to the inclusion of surveillance colonoscopy as part of the management approach in TP53 mutation carriers in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines22.

As the occurrence of gastric cancer in TP53 mutation carriers has not been well documented, we searched the LFS family registry of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and National Cancer Institute to assess the number of cases and ages at diagnosis of gastric cancer in individuals and families with classic LFS or LFS-like histories and germline TP53 mutations. In cases with gastric cancer, we examined whether there were any genotype-phenotype associations, and performed central pathological review of available tumor specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject Selection

Subjects were from families previously enrolled in the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/National Cancer Institute (DFCI/NCI) LFS family registry. This registry was originally assembled by Drs. Li and Fraumeni in 1969: new families have been added via self or physician referral. The registry includes families who meet the classic LFS9 and Li-Fraumeni-like (LFL) Syndrome criteria23, with or without identified TP53 gene mutations. The registry is maintained under a clinical protocol reviewed and approved annually by the Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

The analysis was limited to families with identified pathogenic TP53 mutations. Each pedigree was reviewed to assign the lineage that was the likely source (maternal or paternal) of the TP53 mutation. Pedigrees and available medical record data were reviewed to provide the number, age at diagnosis and histologic features of gastric cancers in the affected lineage of these families, and to evaluate the occurrence of other gastrointestinal tumors. We then looked at the different types of TP53 mutations to explore potential genotype/phenotype correlations. The age range, mean and median ages of diagnosis for the gastrointestinal tumors were calculated. We used Wilcoxon Rank Sum test to compare the median age at diagnosis of gastric cancer in our cohort to the corresponding age of gastric cancer in the general population using data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database from 2001-200524.

Pathology Review

Pathology information was retrieved from medical records and death certificates, and tumor specimens were collected for all available cases of gastric cancers from the registry. In addition, gastric cancer specimens from documented TP53 mutation positive LFS kindreds were provided by our Brazilian collaborators. These cases from Brazil were included only in the pathology review, but not in the frequency analysis of GC. Histological review was performed by a single gastrointestinal pathologist (GYL).

The location of the tumors, histologic type based on the Lauren classification25, and stage were determined along with the presence of any precursor lesions, such as gastric dysplasia, intestinal metaplasia, and chronic active gastritis related to Helicobacter pylori infection.

RESULTS

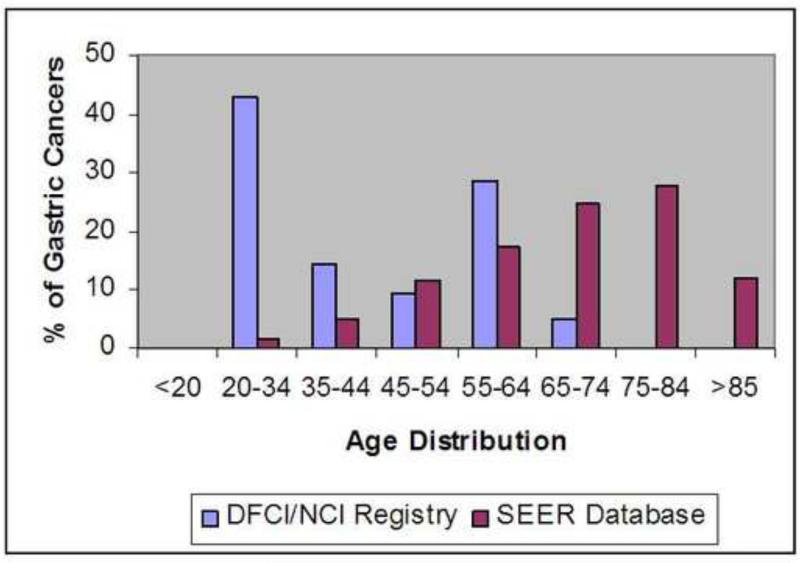

Among 312 families reported in the LFS registry, 62 had confirmed pathogenic TP53 mutations. A total of 429 individuals in the affected lineage of the 62 families had been diagnosed with one or more cancers. Gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancers (here considered as gastric cancer) were diagnosed in 21 (4.9%) individuals from 14 families (Table 2). Nine gastric cancers (42.9%) were confirmed either by medical and pathological records or by death certificates while the remaining 12 cases were reported by family history. Overall, the mean and the median ages at diagnosis of gastric cancer were 43 years and 36 years, respectively (range 24-74 years). The mean and median ages at diagnosis of the 9 confirmed cases of gastric cancer were 46 and 36 years, respectively (range 24-74 years), including 5 subjects with gastric cancer before age 40. Twelve of the 21 (57.1%) cases of gastric cancer in LFS families were diagnosed before age 45 years, with 4 subjects diagnosed before age 30 (the youngest, 24 years). Of note, the individual with documented gastric cancer at 74 years of age was a confirmed mutation carrier. The median age at diagnosis of gastric cancer in this group was significantly younger (p<0.0001) compared to the SEER dataset (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Spectrum of TP53 mutations and ages at diagnosis of gastric cancer in Li Fraumeni Syndrome Families with gastric cancer

| Family | Type | Mutation type in the family | Location of the mutation | Age at diagnosis of gastric cancers^ | Additional primary in gastric cancer patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LFL | Pro301delX344 | Exon8 | 27 | Breast Cancer |

| 2 | LFS | Arg273His | Exon 8 | 60 | - |

| 3 | LFL | Cys275Phe | Exon 8 | 35 | Breast Cancer |

| 4 | LFS | Arg213X | Exon 6 | a.29 | - |

| b.36 | - | ||||

| 5 | LFL | Pro152Leu | Exon 5 | a.45 | - |

| b.52 | - | ||||

| c.58 | - | ||||

| 6 | LFS | Glu339X | Exon 10 | 40 | - |

| 7 | LFS | Arg273Cys | Exon 8 | 60 | Soft Tissue Sarcoma |

| 8 | LFL | 686-687delGT | Exon 7 | a.74 | NHL, Pancreatic Ca |

| b.31 | - | ||||

| 9 | LFS | Arg248Gln | Exon 7 | 59 | - |

| 10 | LFS | Glu258Lys | Exon 7 | a.24 | Brain |

| b.60 | - | ||||

| c.62 | - | ||||

| 11 | LFL | Arg213X | Exon 6 | a.29 | Lung Cancer |

| b.32 | - | ||||

| 12 | LFL | Arg196X | Exon 6 | 31 | - |

| 13 | LFS | Arg110Pro | Exon 4 | 32 | - |

| 14 | LFS | Arg158His | Exon 5 | 32 | - |

Letters indicate different individuals with gastric cancers in the same family.

NHL: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Figure 1.

Distribution of Gastric Cancer by Age in DFCI/ NCI LFS registry and the SEER database

Thirty-two (51.6%) of the 62 families had at least one family member with gastrointestinal cancer, including gastric, esophageal, colorectal or pancreatic cancers. There were 14 (22.6%) families with one or more cases of gastric cancer, 5 families (8.1%) with two or more cases of gastric cancer, and 6 (9.6%) families with cases of both gastric and colorectal cancers. In examining the pedigrees of the 62 families for additional gastrointestinal tumors occurring in the affected lineage, we found 28 (4.8%) colorectal cancers (median age at diagnosis of 53.0 years) and 7 (1.2%) pancreatic cancers (median age of 60.5 years). Overall, 17 (27.4%) of 62 families had cases of gastric or colorectal cancer diagnosed before age 50 years.

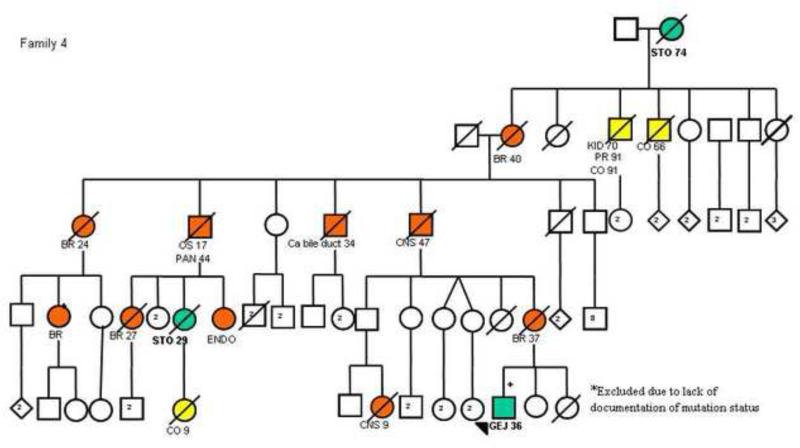

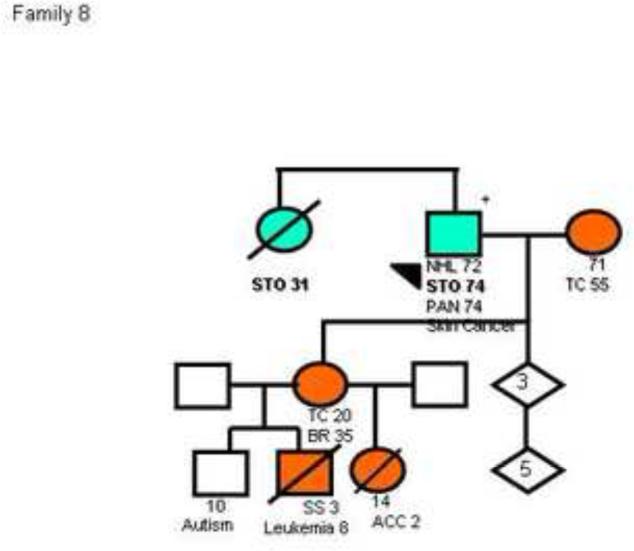

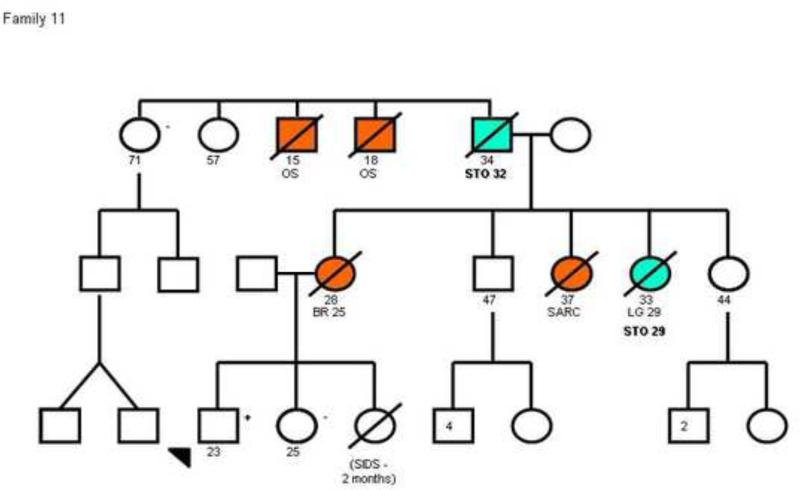

Details of TP53 mutation type were available for all families with gastric cancer cases. Two families (families 4 and 11 shown in figure 2) had the same mutation in exon 6 (Arg213X). However, the other 12 families had 12 different mutations distributed along exons 4 to 10 with no clear genotype-phenotype correlation (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Pedigree plots of 3 families (Families 4, 8 and 11) with multiple cases of early onset gastric cancers and a known TP53 mutation. The circles represent females while the squares represent males. Open symbols indicate no neoplasm and filled symbols represent those with cancer; crossed symbols indicate deceased individuals. Arrows indicate probands, allpositive for a TP53 mutation. STO/GEJ, stomach/gastroesophageal junction cancer; BR, breast cancer; SS, soft-tissue sarcomas; OS, osteosarcoma; CNS, central nervous system cancer; CO, colon cancer; PAN, pancreatic cancer; LG, lung cancer; ENDO, endometrial cancer; KID, kidney tumor; PR, prostate cancer; ACC, adrenal cortical cancer; TC, thyroid cancer. Numbers after the symbols for the type of cancer indicate age at death or age at diagnosis. The pedigrees have been de-identified to protect confidentiality. The pedigree of family 8 has been previously published42.

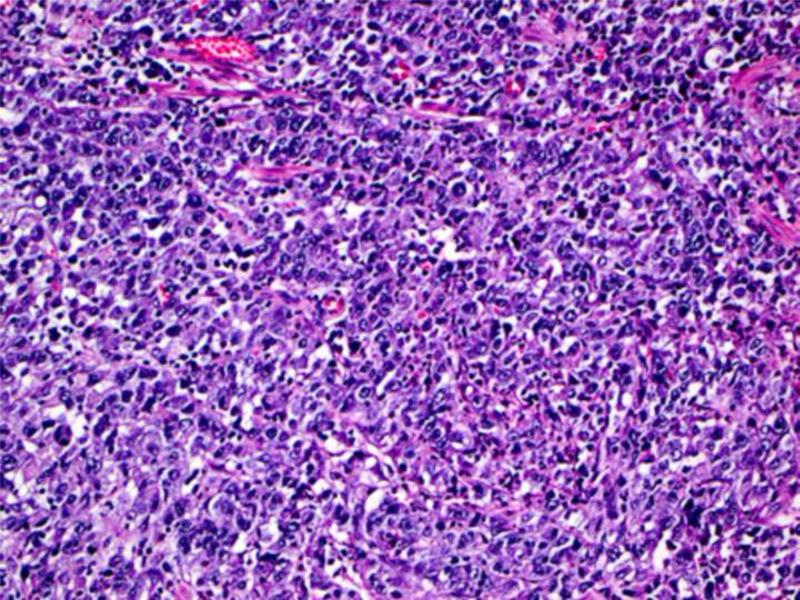

Characteristics of gastric tumors

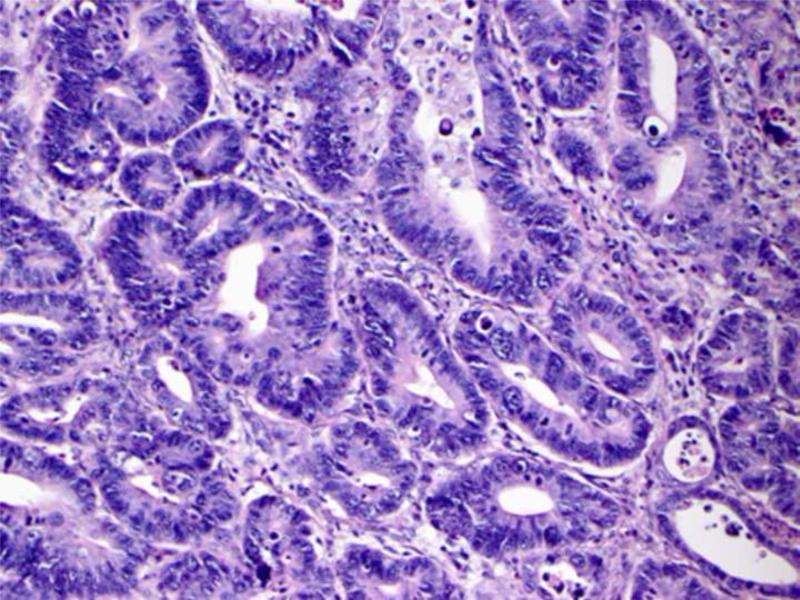

Histologic material was available for 5 of the 9 confirmed cases of gastric cancer in the DFCI/NCI registry and the two additional cases obtained from Brazil (Table 4). Four of the 7 tumors arose in the proximal region of the stomach, two in the antrum, and one in the fundus; all were advanced at the time of diagnosis. Five of the cases had an intestinal morphotype (3 moderately differentiated and 2 well differentiated) while two had the diffuse type with signet ring cells (Figure 3). Two of the tumors were diagnosed at stage pT2, four at stage pT3 and one at stage pT4. Of note, one of the cases from Brazil was a 12 year old who had metastatic gastric cancer at presentation.

Figure 3.

Example of intestinal type moderately differentiated (A) and diffuse type gastric adenocarcinoma (B) observed in our cohort

Gastric dysplasia was not identified in any of the histopathologic material available for review. Very focal intestinal metaplasia was noted in a single case, while two cases had features suggestive of Helicobacter pylori inflammation. Although stains for this organism had not been performed, one case had prominent lymphoid hyperplasia and another had chronic active gastritis in the surrounding mucosa.

DISCUSSION

In our series of 62 families with TP53 mutations in the DFCI/NCI LFS family registry, 14 (22.6%) families had at least one member diagnosed with gastric cancer. Of 429 family members with cancer, 21 had gastric cancer (4.9%). Similar to other hereditary cancer syndromes, the age at diagnosis of gastric cancer in LFS was much younger than in the general population in the United States (median age at diagnosis at 36 years versus 71 years, p<0.0001). Although the tumors specimens available for review were limited in number and amount of tissue, both intestinal and diffuse type gastric cancers were seen, with 50% of the tumors located in the proximal stomach.

Although literature surveys indicate that gastric cancer is an uncommon manifestation of LFS 26-29, its occurrence has featured a remarkably young age at diagnosis. In 2001, Nichols et al reported that among 738 cancer-affected TP53 mutation carriers and their first-degree relatives from the original DFCI/NIH LFS registry and from the review of the literature through 1999, there were 23 (3.1%) cases of carcinoma of the stomach17. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 Mutation Database30 compiles all kindreds with TP53 mutations reported in the published literature since 1989 (DFCI/NCI families are not included). Among 899 tumors reported in individuals with TP53 germline mutations, only 16 (1.8%) are gastric tumors. Based on case reports of LFS or LFS-like families associated with TP53 mutations in Japan and Korea, gastric cancer in LFS seems more prevalent in Asian populations with high rates of gastric cancer31-35. This finding suggests that individuals with germline TP53 mutation are susceptible to the carcinogenesis effects of Helicobacter pylori infection in endemic areas. The interaction may be analogous to the smoking-related lung cancer and the radiation-related sarcomas reported in LFS. These studies also suggest that TP53 mutations may be informative in families with early onset gastric cancer, especially when more characteristic LFS-related tumors are present in the families. Of note, sporadic TP53 mutations can be found in almost every tumor with a prevalence of sporadic mutations in stomach cancer of 20%36.

While adding to previous data on the occurrence of gastric cancer in LFS families, our study has limitations based on its retrospective nature, incomplete and missing data, and inability to confirm the cancer diagnoses and genotypes for all subjects. Although gastric cancers on average were diagnosed at much younger ages than the SEER population, some of the tumors occurred at ages above 50 years. As not all individuals with gastric cancer had mutation testing, some of the cancers at older ages may have represented sporadic cases. Furthermore, there is always a risk of misclassification associated with abdominal tumors, since the site of origin may be difficult to discern, even at surgery37. These factors may have contributed to an overestimate of TP53 mutations associated with gastrointestinal tumors. To minimize these errors, we carefully reviewed each pedigree and excluded gastric cancers that were either on the unaffected side of the family or were distant from the proband with the pathogenic TP53 mutation. We also attempted to confirm as many gastric cancer diagnoses as possible. Previous studies evaluating the completeness and accuracy of family history reporting of cancers have found satisfactory reporting of gastrointestinal and intra-abdominal tumors by family members38, 39. In addition, the majority (81%) of gastric cancer cases in our study were either probands or first- and second-degree relatives of mutation carriers. Prior studies have reported that the degree of closeness to an affected relative correlates with the accuracy of cancer reporting, which is highest for tumors among first-degree relatives37-39.

Despite the difficulties of studying an uncommon manifestation of a rare syndrome, our findings suggest an excess occurrence of early-onset gastric cancer in TP53 mutation-positive families. The results are similar to our other observations on colorectal cancer in LFS21, and may have implications for diagnostic and preventive interventions in selected families. Due to the broad array of cancers associated with LFS and the lack of effective screening modalities for most LFS-related cancers, such as sarcomas and brain tumors, the measures aimed at early cancer detection are limited. The only available guidelines for cancer screening in TP53 carriers are from the NCCN and suggest that screening for breast and colorectal cancers is advisable 22. Our group has reported a pilot study evaluating the role of whole-body PET (positron emission tomography)/CT (computerized tomography) scan in 15 LFS families.40 In that study a tumor of the gastro-esophageal junction was detected by scan and confirmed with esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD). Given the colonoscopy recommendations for surveillance of colorectal cancer, the addition of periodic screening with EGD in germline TP53 carriers may be reasonable to consider, particularly in LFS families in which at least one member has gastric cancer. The early age at diagnosis in comparison to the general population suggests that surveillance may need to begin in young adults. Nevertheless, we need to consider the data showing that upper GI endoscopies were frequently normal in patients with diffuse gastric cancer which was eventually diagnosed after prophylactic surgery41. More data are needed to establish the effectiveness and appropriate intervals for screening with EGD in TP53 carriers, in addition to targeted interventions based on individual family history.

In summary, although it is an uncommon manifestation of LFS, early–onset gastric cancer appears to be a component of the spectrum of tumors that are associated with this familial syndrome. Further studies are needed to determine the role of EGD as well as other cancer detection measures among individuals with TP53 germline mutations.

Table 3.

Pathology Review of the available specimens

| Patient | Sex | Age at Dx | Location | Histology | Grade | Stage | GED/IM | HP^ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | F | 29 | Proximal stomach | DGC(SRC) | - | pT3 | -/- | No evidence |

| 4b | M | 36 | Proximal Stomach | DGC(SRC) | - | pT3 | -/- | No evidence |

| 9 | M | 74 | Antrum | IGC | 3 | pT2 | -/- | Mild chronic inflammation |

| 12 | F | 29 | Proximal Stomach | IGC | 2 | pT2 | -/- | No evidence |

| 3 | F | 35 | Antrum | IGC | 2 | pT3 | -/+ | Mild chronic inflammation |

| B1 | M | 39 | Fundus | IGC | 3 | pT3 | -/- | No evidence |

| B2+ | M | 12 | Proximal stomach | IGC | 1 | pT4 | +/- | No evidence |

DGC: Diffuse gastric cancer; SRC: Signet Ring Cells: IGC: Intestinal type gastric cancer

GED: Gastric epithelial dysplasia; IM: Intestinal metaplasia; HP Helicobacter Pylori

“Mild chronic inflammation” inactive gastritis, is not a specific features of HP.

The pathology report was available for review of the primary site. Liver and peritoneal metastasis images were available for review.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Li Fraumeni patients and families who kindly consented over the years to be part of the DFCI/NCI LFS registry.

Supported by Charles A. King Trust, Bank of America Fellowship, Co-Trustee (Boston, MA) and The Humane Society of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (S Masciari) and the US National Cancer Institute grant K24 CA 113433 (S Syngal). This work was supported in part by the STARR Foundation. Presented in part at the Digestive Disease Week, San Diego, CA, May 17-22, 2008; and 3rd International Workshop on Mutant p53, Lyon, France, November 15-16, 2007. This work was conducted with support from the Scholars in Clinical Science Program of Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the National Institutes of Health. Genetic testing in CR (L Foretova) was supported by grant MZ0 MOU 2005.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- LFS

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome

- HDGC

Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer

- DFCI/NCI

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/National Cancer Institute

- LFL

Li-Fraumeni-like

- SEER

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- PET/CT

positron emission tomography/computerized tomography

- EGD

esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

Footnotes

No Conflict of Interest exists for all the authors above.

References

- 1.Horner MJRL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Lewis DR, Eisner MP, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/ based on November 2008 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site

- 2.Zanghieri G, Di Gregorio C, Sacchetti C, et al. Familial occurrence of gastric cancer in the 2-year experience of a population-based registry. Cancer. 1990 Nov 1;66(9):2047–2051. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901101)66:9<2047::aid-cncr2820660934>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Gentile A. Family history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1992 Jul 1;70(1):50–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<50::aid-cncr2820700109>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gayther SA, Gorringe KL, Ramus SJ, et al. Identification of germ-line E-cadherin mutations in gastric cancer families of European origin. Cancer Res. 1998 Sep 15;58(18):4086–4089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998 Mar 26;392(6674):402–405. doi: 10.1038/32918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira C, Bordin MC, Grehan N, et al. Screening E-cadherin in gastric cancer families reveals germline mutations only in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer kindred. Hum Mutat. 2002 May;19(5):510–517. doi: 10.1002/humu.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suriano G, Yew S, Ferreira P, et al. Characterization of a recurrent germ line mutation of the E-cadherin gene: implications for genetic testing and clinical management. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Aug 1;11(15):5401–5409. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaurah P, MacMillan A, Boyd N, et al. Founder and recurrent CDH1 mutations in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Jama. 2007 Jun 6;297(21):2360–2372. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr. Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome? Ann Intern Med. 1969 Oct;71(4):747–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Mulvihill JJ, et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988 Sep 15;48(18):5358–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garber JE, Goldstein AM, Kantor AF, Dreyfus MG, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Li FP. Follow-up study of twenty-four families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cancer Res. 1991 Nov 15;51(22):6094–6097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varley JM, McGown G, Thorncroft M, et al. An extended Li-Fraumeni kindred with gastric carcinoma and a codon 175 mutation in TP53. J Med Genet. 1995 Dec;32(12):942–945. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.12.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varley JM, McGown G, Thorncroft M, et al. Germ-line mutations of TP53 in Li-Fraumeni families: an extended study of 39 families. Cancer Res. 1997 Aug 1;57(15):3245–3252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleihues P, Schauble B, zur Hausen A, Esteve J, Ohgaki H. Tumors associated with p53 germline mutations: a synopsis of 91 families. Am J Pathol. 1997 Jan;150(1):1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birch JM, Blair V, Kelsey AM, et al. Cancer phenotype correlates with constitutional TP53 genotype in families with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Oncogene. 1998 Sep 3;17(9):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hisada M, Garber JE, Fung CY, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Li FP. Multiple primary cancers in families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Apr 15;90(8):606–611. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichols KE, Malkin D, Garber JE, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Li FP. Germ-line p53 mutations predispose to a wide spectrum of early-onset cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001 Feb;10(2):83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varley JM, Evans DG, Birch JM. Li-Fraumeni syndrome--a molecular and clinical review. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strong LC, Williams WR. The genetic implications of long-term survival of childhood cancer. A conceptual framework. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1987;9(1):99–103. doi: 10.1097/00043426-198721000-00017. Spring. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartley AL, Birch JM, Kelsey AM, Marsden HB, Harris M, Teare MD. Are germ cell tumors part of the Li-Fraumeni cancer family syndrome? Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1989 Oct 15;42(2):221–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(89)90090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong P, Verselis SJ, Garber JE, et al. Prevalence of early onset colorectal cancer in 397 patients with classic Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2006 Jan;130(1):73–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NCCN National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v1.2008: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment:Breast and Ovarian: Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/genetics_screening.pdf.

- 23.Birch JM, Hartley AL, Tricker KJ, et al. Prevalence and diversity of constitutional mutations in the p53 gene among 21 Li-Fraumeni families. Cancer Res. 1994 Mar 1;54(5):1298–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ries LAG MD, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF, Lewis DR, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2008. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/ based on November 2007 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site

- 25.Lauren P. The Two Histological Main Types of Gastric Carcinoma: Diffuse and So-Called Intestinal-Type Carcinoma. an Attempt at a Histo-Clinical Classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman DL, Kadan-Lottick NS, Whitton J, et al. Increased risk of cancer among siblings of long-term childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Aug;14(8):1922–1927. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang D, McNally R, Kelsey A, Birch JM. Cancer incidence and mortality among the parents of a population-based series of 2604 children with cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003 Jun;12(6):538–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chompret A, Brugieres L, Ronsin M, et al. P53 germline mutations in childhood cancers and cancer risk for carrier individuals. Br J Cancer. 2000 Jun;82(12):1932–1937. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans DG, Birch JM, Thorneycroft M, McGown G, Lalloo F, Varley JM. Low rate of TP53 germline mutations in breast cancer/sarcoma families not fulfilling classical criteria for Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Med Genet. 2002 Dec;39(12):941–944. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.12.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.IARC International Agency for Research on Cancer: TP53 Mutation Database,R12 release. 2007 Nov; http://www-p53.iarc.fr/

- 31.Kim IJ, Kang HC, Shin Y, Yoo BC, Yang HK, Park JG. Familial gastric cancers with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome: a case repast. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jul 14;11(26):4124–4126. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada H, Shinmura K, Okudela K, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel germ line p53 mutation in familial gastric cancer in the Japanese population. Carcinogenesis. 2007 Sep;28(9):2013–2018. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliveira C, Ferreira P, Nabais S, et al. E-Cadherin (CDH1) and p53 rather than SMAD4 and Caspase-10 germline mutations contribute to genetic predisposition in Portuguese gastric cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004 Aug;40(12):1897–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keller G, Vogelsang H, Becker I, et al. Germline mutations of the E-cadherin(CDH1) and TP53 genes, rather than of RUNX3 and HPP1, contribute to genetic predisposition in German gastric cancer patients. J Med Genet. 2004 Jun;41(6):e89. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.015594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim IJ, Kang HC, Shin Y, et al. A TP53-truncating germline mutation (E287X) in a family with characteristics of both hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2004;49(11):591–595. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strickler JG, Zheng J, Shu Q, Burgart LJ, Alberts SR, Shibata D. p53 mutations and microsatellite instability in sporadic gastric cancer: when guardians fail. Cancer Res. 1994 Sep 1;54(17):4750–4755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider KA, DiGianni LM, Patenaude AF, et al. Accuracy of cancer family histories: comparison of two breast cancer syndromes. Genet Test. 2004;8(3):222–228. doi: 10.1089/gte.2004.8.222. Fall. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Douglas FS, O'Dair LC, Robinson M, Evans DG, Lynch SA. The accuracy of diagnoses as reported in families with cancer: a retrospective study. J Med Genet. 1999 Apr;36(4):309–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murff HJ, Spigel DR, Syngal S. Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. Jama. 2004 Sep 22;292(12):1480–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masciari S, Van den Abbeele AD, Diller LR, et al. F18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography screening in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Jama. 2008 Mar 19;299(11):1315–1319. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norton JA, Ham CM, Van Dam J, et al. CDH1 truncating mutations in the E-cadherin gene: an indication for total gastrectomy to treat hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2007 Jun;245(6):873–879. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000254370.29893.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chao MM, Levine JE, Ruiz RE, et al. Malignant triton tumor in a patient with Li-Fraumeni syndrome and a novel TP53 mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007 Dec;49(7):1000–1004. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]