Abstract

The innate immune system is evolutionary and ancient and is the pivotal line of the host defense system to protect against invading pathogens and abnormal self-derived components. Cellular and molecular components are involved in recognition and effector mechanisms for a successful innate immune response. The complement lectin pathway (CLP) was discovered in 1990. These new components at the complement world are very efficient. Mannan-binding lectin (MBL) and ficolin not only recognize many molecular patterns of pathogens rapidly to activate complement but also display several strategies to evade innate immunity. Many studies have shown a relation between the deficit of complement factors and susceptibility to infection. The recently discovered CLP was shown to be important in host defense against protozoan microbes. Although the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by MBL and Ficolins reveal efficient complement activations, an increase in deficiency of complement factors and diversity of parasite strategies of immune evasion demonstrate the unsuccessful effort to control the infection. In the present paper, we will discuss basic aspects of complement activation, the structure of the lectin pathway components, genetic deficiency of complement factors, and new therapeutic opportunities to target the complement system to control infection.

1. Introduction

The innate immune system represents the first line of defense against microbial infections. The defense is a nonspecific response to infection and comprehends three important processes, namely, pathogen identification and activation of humoral and cellular responses, pathogen destruction and clearance, and activation of the adaptive immune system. The complement system is one of the main players of the innate immune system, and its activation results in pathogen opsonisation, production of anaphylotoxins (which recruit cells to the site of infection), phagocytosis, and lysis.

Nowadays, the importance of the complement lectin pathway (CLP) has received attention mainly in bacterial infections. Knowledge on the role of the lectin pathway in parasitic infections is scarce. Considering the long-standing evolutionary interplay between parasitic infections and innate defense mechanisms, a better understanding of the complement system in counter parasitic infections is necessary. In this paper, we will highlight the important aspects of the current knowledge on CLP activation and resistance by protozoan parasites, particularly the trypanosomatids. We will discuss the molecular mechanisms of lectin pathway activation, mechanisms of immune evasion by pathogens, genetic association studies on susceptibility of infection, and the advances in complement-based therapeutics to control infection.

2. Complement Lectin Pathway (CLP) Activation

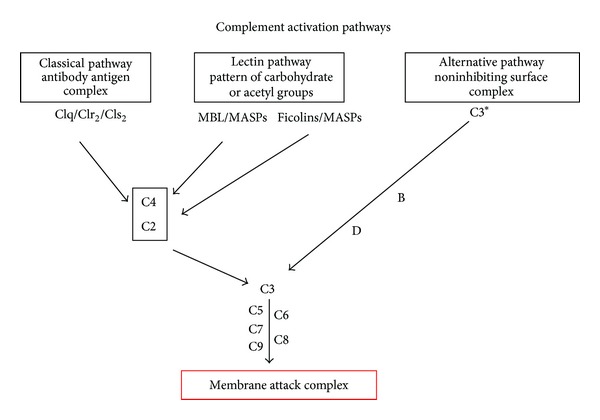

The lectin pathway is initiated when MBL (mannan-binding lectin) or ficolins (L-H-M) bind to patterns of carbohydrates [1–3] or acetyl groups on the surface of protozoan, virus, fungi, or bacteria [4]. These patterns are found in three pairs of protease serine complexes, namely, mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease (MASPs) such as MASP-1, MASP-2, MASP-3, MAP-19, and MAP-44. When recognition molecules bind to a pattern, the MASPs are activated [5–7]. MASP (MASP-1 and -2) cleaves to the components C2 and C4. The C4b fragment (product of C4 cleavage) binds to the pathogen surface and associates with C2a to form the C3-convertase (C4b2a, similar to the C3-convertase of the classical pathway) (see Figure 1). Once C3 cleaves, the C3b fragment can bind to the pathogen surface to activate the alternative pathway (Figure 1), or it can bind to the C4b2a (classical or lectin pathway C3-convertase) to form the C5-convertase (C4b2a3b). C3b can also bind to the alternative pathway C3-convertase, C3bBb, and form the C5-convertase C3bBb3b. The C5-convertase cleaves C5 into C5a and C5b. C5b then binds to the pathogen surface to form an anchor, together with C6, C7, and C8, to support the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) with several C9 molecules.

Figure 1.

Complement activation pathways. Classical, lectin, and alternative pathways are activated in different ways and culminate with the direct destruction of pathogens via the membrane attack complex.

3. Components of the Lectin Pathway: Structural and Functional Considerations

3.1. MBL

MBL has a bouquet-like structure which is similar to the classical pathway initiator protein C1q [8, 9]. MBL is 32 kDa protein that forms oligomeric structures ranging from dimers to hexamers [8]. The protein is characterised by a lectin (or carbohydrate-recognition domain (CRD)), a hydrophobic neck region, a collagenous region, and a cysteine-rich N-terminal region [8, 10, 11]. Weis et al. [8] demonstrated that each domain binds to a Ca2+ ion and coordinates the interaction with the 3- and 4-hydroxyl groups of specific sugars, such as GlcNAc, mannose, N-acetyl-mannosamine, fucose, and glucose. MBL binds to several microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, and protozoa parasites such as Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania sp., and Plasmodium sp. [12–15].

3.2. Ficolins

Three members of the ficolin family of proteins have been described in humans, such as L-ficolin (or ficolin-2), H-ficolin (or ficolin-3 or Hakata antigen), and M-ficolin (or ficolin-1) [16–19]. Although previous works [3, 6, 19, 20] found the L- and H-ficolins in the human plasma in the form of soluble proteins, the presence in serum of M-ficolin was only demonstrated recently [21]. This ficolin is not hepatically synthesized and is able to have a similar complement activation. Ficolin proteins are composed of a short N-terminal region with one or two cysteine residues, followed by a collagen-like domain, a short link region, and a subsequent fibrinogen-like domain [1]. Ficolin proteins form trimeric subunits through the binding of a collagen-like domain [1, 22]. These subunits in turn assemble into active oligomers through the binding of four subunits via disulfide bridges at the N-terminal regions [1, 23]. Ficolins recognize acetylated carbohydrates through the C-terminal fibrinogen-like domain [1, 2, 24]. They bind mainly to the terminal GlcNAc residues, which are widely present on a variety of pathogens but not in human cells [1, 3, 6, 25, 26].

L-ficolin is an oligomeric protein consisting of 35 kDa subunits [22, 27]. Similar to MBL and C1q, the overall structure of L-ficolin resembles a “bouquet.” The protein is a tetramer consisting of 4 triple helices formed by 12 subunits [22]. Although the protein binds mainly to acetylated carbohydrates [2, 26], it can also recognize other acetylated molecules, such as lipoteichoic acid on the surface of Gram-positive bacteria, peptidoglycan, surface lipopolysaccharide of Gram-negative bacteria, β-1,3-glucans of fungi, envelope glycoconjugate of viruses, and glycosylated proteins on the surface of T. cruzi [1, 14, 28–31].

H-ficolin is a protein of 34-kDa and thought to form oligomers of different sizes [3, 27, 32, 33]. H-ficolin has been shown to bind to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and fucose, but not to mannose and lactose [1, 3]. Although the protein binds to GlcNAc, its affinity seems to be very weak compared with that of L-ficolin [34]. Structural studies demonstrated that the fibrinogen-like domain of H-ficolin could not be cocrystallized with many acetylated compounds tested including GlcNAc [1]. H-ficolin has been shown to bind to lipopolysaccharides and recognizes surface exposed carbohydrates on pathogens such as Salmonella typhimurium and T. cruzi [6, 14, 35].

M-ficolin was initially reported to be expressed on the surface of peripheral blood monocytes and promonocytic U937 cells [36]. More recently, the protein was reported to be present in human plasma in significant amounts [25, 37]. M-ficolin binds to acetylated carbohydrates, such as GlcNAc and GalNAc [36, 38, 39], and only the human ficolin recognizes sialic acid [34]. In addition, M-ficolin has also been shown to bind to C-reactive protein (CRP) and to fibrin [24, 40]. The protein also recognizes Streptococcus sp. bacteria and the protozoa parasite T. cruzi [14, 41]. M-ficolin can independently activate the lectin pathway.

3.3. MASPs

MBL-associated serine proteases (MASPs) are soluble serine proteases present in human serum. MASP-1, MASP-2, and MASP-3 are synthesised as proenzymes with apparent molecular weights of 90 kDa, 74 kDa, and 94 kDa, respectively. They are composed of an N-terminal CUB (Complement C1r/C1s, Uefg, Bmp1) domain (CUB1), followed by a Ca2+-binding type epidermal growth factor- (EGF-) like domain, a second CUB domain (CUB2), two complement control protein modules (CCP1 and CCP2), a short linker, and a chymotrypsin-like serine protease (SP) domain [42]. Binding of the MBL-MASP or ficolin-MASP complexes to their ligands autoactivates the MASPs by promoting proteolytic cleavage of arginine-isoleucine residues within the linker region, resulting in two polypeptides held together by disulfide bound and activation of the enzymes. The N-terminal domains and linker region preceding the cleavage sites are called A-chain, whereas the SP domain (the catalytic domain) is the B-chain. The SP domain in MASP-2 was shown to efficiently bind and cleave C2, whereas the C4 cleavage required the CCP modules [43]. The MASPs (including MAP19) form homodimers. Each homodimer individually associates with MBL and ficolins through the N-terminal CUB1-EGF modules in a Ca2+-dependent manner although the CUB2 also contributes to these interactions [42, 44].

The enzyme MASP-2 has been shown to play a fundamental role in lectin pathway activation by cleaving C2 and C4, which in turn generate the C3-convertase C4b2a [6, 45]. MASP-2 is the main enzyme involved in the activation of the lectin pathway. The enzyme MASP-1 cleaves C2 as efficiently as MASP-2, but it does not show activity toward C4 and probably acts by accelerating the C3-convertase formation [46, 47]. The enzyme MASP-3 does not seem to be involved in C2 or C4 cleavage. MASP-3, together with the protein MAP 44, could be involved in downregulating the lectin pathway activation to avoid host self-damage through superactivation of the complement system. However, this assumption remains speculative [48, 49].

4. Lectin Pathway Activation by Protozoan Parasites

Understanding the mechanism of activation of lectin pathway is necessary to dissect the strategies of protozoan parasites to evade complement [50]. Recent reports in Leishmania sp, Plasmodium sp, T. cruzi and Giardia intestinalis [14, 15, 51, 52] have shown an efficient activation of lectin pathway. MBL binds to lipophosphoglycans on Leishmania and activates the lectin pathway with promastigote lysis [51, 53]. In T. cruzi, MBL as L- and H-ficolin is bound to N- and O-glycosylated molecules on the surface of T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes with a rapid activation of the complement. Furthermore, normal human serum depleted of MBL and ficolins reduced by 70% the C3b and C4b depositions on parasite surface and complement-mediated lysis [14, 54]. Moreover, the complement-mediated lysis of T. cruzi in nonimmune serum at early stages was demonstrated to be dependent on MASP-2 and C2, which confirmed the involvement of the lectin pathway [14]. Depletion of C1q from nonimmune human serum had no effect in T. cruzi complement activation and lysis [14, 54], which confirmed that at early stages of infection, the lectin pathway is the most efficient. Supporting findings demonstrated that, in the absence of the lectin pathway (nonimmune serum depleted of MBL and ficolins), almost no activation of the classical pathway occurs. Taken together, during the innate immunity (in absence of specific antibodies), the classical pathway would be very inefficient in the clearance of the parasites. Yoshida and Araguth [55] have shown that natural antibodies could lead to complement-mediated lysis of T. cruzi trypomastigotes, but the lysis was dependent on the source of serum. Complement-mediated lysis of T. cruzi trypomastigotes in presence of anti-α-galactosyl antibodies from Chagas disease patients has been shown [56, 57], to confirm the role of the classical pathway after the development of a specific antibody response. Since MBL also binds to IgM, IgA, and IgG antibodies [58–60], both pathways (classical and lectin) could be synergistically activated in the presence of specific antibodies and in chronic infections.

Complement-mediated lysis of T. cruzi was inefficient in serum-deficient C2 [14]. Since C2 is required for C3-convertase formation by the classical and lectin pathways, but not for the alternative pathway, the alternative pathway is inefficiently activated by T. cruzi [14]. The kinetics of complement-mediated lysis with serum treated with EGTA (and MgCl2) to chelate Ca2+ (classical and lectin pathways are not functional under these conditions) confirmed that the alternative pathway is slowly activated by T. cruzi and Leishmania sp. [54, 61, 62]. Alternative pathway seems to have less importance at the early activation by T. cruzi trypomastigotes because of the poor binding of factor b to the parasite surface [63]. Other authors [62, 64] also showed a slow activation of the complement system in Leishmania spp., using serum-deficient C2. This result indicates that the alternative pathway activation can be delayed in the absence of the classical and lectin pathways. Moreover, the activation of lectin pathway results in C3-convertase formation, which in turn cleaves C3 into C3b to trigger the alternative pathway. This synergistic activation and the rapid deposition of C4 and C2 factors convert the lectin pathway in the most vital time [14, 54, 61].

Besides trypanosomatids, a variety of microorganisms have been shown to activate the lectin pathway. For example, Plasmodium sp. activates the lectin pathway [15]. MBL and ficolins have also been shown to recognize Giardia sp., resulting in CLP activation [52]. Human serum depleted of MBL and L-ficolins that failed to destroy the parasites demonstrated that the lectin pathway is involved to control Giardia infections [52]. Several other pathogens including bacteria and viruses were also shown to activate the lectin pathway [50, 65]. Altogether, the importance of the lectin pathway in pathogen recognition at initial stages of infection is demonstrated.

5. Mechanisms of Complement Evasion by Protozoan Parasites

Several molecules involved in complement evasion have been described in different pathogens and have been recently summarized in a review by [66]. Briefly, we can reinforce that the main mechanism to complement evasion is to inhibit the progression of the complement cascade to prevent the C3-convertase formation. T. cruzi uses different molecules to block the complement cascade. Complement C2 receptor inhibitor trispanning (CRIT) is a surface molecule expressed at the metacyclic trypomastigotes stage (infectious state) and inhibits the C3-convertase [14, 61]. GP160, also called complement regulatory protein (CRP), is a molecule expressed in T. cruzi trypomastigotes that binds to C3b and C4b and dissociates the classical and alternative pathways of C3-convertase [67, 68].

Overexpression of the gene CRP and CRIT in T. cruzi epimastigote stage (the insect stage is sensitive to complement-mediated lysis) conferred complement resistance to the parasites, respectively [61]. Some authors [69] demonstrated the complement inhibition before C3-convertase formation. Calreticulin (CRT) present at the surface of trypomastigotes is able to bind C1q and MBL to alter the classic and lectin pathways [70–72]. Similarly, an 87 to 93 kDa protein identified on the surface of T. cruzi trypomastigotes, called trypomastigotes-decay accelerating factor (T-DAF), was shown to share cDNA similarity to human DAF and inhibits parasite lysis [73]. Another molecule shown to inhibit the C3-convertase formation in T. cruzi was the gp58/68 [74]. Purified gp58/68 inhibited the formation of cell-bound and fluid-phase alternative pathway C3-convertase in a dose-dependent fashion. Different from DAF, gp58/68 was unable to dissociate the C3-convertase. However, the inhibition of the C3-convertase seems to be dependent on its association with factor B (rather than with C3b) [74]. Gp58/68 provides trypomastigotes with an additional potential mechanism to escape complement lysis by the alternative pathway.

In other trypanosomatids such as Leishmania sp., the surface glycoprotein, also known as major surface protease, was shown to be the major C3b acceptor [75]. C3b binding to GP63 results in its conversion to iC3b (inactive C3b) to prevent the C3-convertase formation on the parasite surface [76]. Furthermore, surface deposited iC3b is recognized by the complement receptor 3 (also known as MAC-1), resulting in parasite phagocytosis by macrophages [76], in which the parasites can multiply and further develop. Deletion of the gene coding for the Golgi GDP-mannose transporter LPG-2, required for the synthesis of surface lipophosphoglycan, resulted in parasites highly susceptible to complement-mediated lysis [77]. LPG-2 null L. major was incapable to establish macrophage infection and presented diminished mice infection. L. major releases the MAC (C5b-9) deposited on its surface during complement activation [78], to demonstrate that the parasite combines different evasion mechanism to the complement system.

For the African trypanosome T. brucei, evasion of the complement system is dependent on the expression of a single variant surface glycoprotein (VSGs) that forms a coat on the parasite surface [79, 80]. This parasite has a repertoire of more than 1000 genes (and pseudogenes) coding for VSGs, which are anchored to the parasite surface by glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Once the host develops a specific antibody response against the surface VSG, a switch in gene expression occurs, resulting in a different surface coat, which allows the parasite to escape the host antibody response [81]. Furthermore, the removal of immune complexes deposited on the parasite surface has also been shown to be dependent on VSGs [79, 80]. Host immunoglobulins (Ig) form immune complexes with VSG on the cell surface. They are rapidly removed by a hydrodynamic force generated by the parasite motility that results in the transfer of the immune complexes to the posterior cell pole of the cell, in which they are endocytosed. The backward movement of immune complexes on the cell surface seems to require the forward parasite motility and to be independent of endocytosis and actin function [80].

Complement receptors capable of inhibiting complement activity have been shown in Schistosoma sp. A 97 kDa protein called paramyosin (also known as schistosoma complement inhibitory protein-1) was reported to bind to the complement components C8 and C9 and inhibit C9 polymerization [82, 83]. The protein CRIT (aforementioned to inhibit classical and lectin pathway activation in T. cruzi and humans) was first identified in a cDNA library of S. haematobium [84, 85]. This protein was shown to be expressed on the surface tegumental plasma membrane and tegumental surface pits of adult schistosomes [85]. The protein binds to C2 and inhibits C3-convertase formation [86]. Schistosomes were also shown to acquire the host protein DAF from erythrocytes [87]. Schistosomes containing surface-bound DAF were able to evade complement-mediated lysis.

To summarize, protozoan parasites display several mechanisms to evade the complement system. The parasite needs to survive to produce the infection. Protozoa invade the host cell rapidly to be protected intracellularly. This strategy is used by some strains of T. cruzi. Other way to block the complement pathway is expressing receptor for complement on the parasite surface [50]. A broad strategy should be the expression of a layer at the surface. This strategy seems to be used by Leishmania with LPG and in T. brucei with VSG and the antigenic variation. Finally, the remotion of immune complex from parasite surface seems to be important to evade the complement and phagocytosis by opsonisation. Shedding was shown in Leishmania and in T. cruzi [88]. In addition, T. brucei would remove complement factors and antibodies to evade the innate immunity.

6. Deficiencies of the Lectin Pathway and Susceptibility to Parasitic Infections: Studies in Human Populations

6.1. MBL

MBL may contribute to the control of parasitemia during malaria infections. MBL genotype and phenotype were assessed in a prospective matched-control study of Gabonese children with malaria [89]. The 100 patients with severe malaria both had significantly more frequently low MBL levels, defined as <200 ng/mL (0.35 versus 0.19, P = 0.02) and a higher frequency of mutant alleles at codons 54 and 57 (0.45 versus 0.31, P = 0.04) compared to 100 children with mild malaria. Matching was performed for sex, age, and provenance. These findings were confirmed in other study where the MB12 C missense mutation was found in 35% of healthy controls and in 42% of infected but asymptomatic children, in contrast to 46% of children with severe malaria (P = 0.007) [15]. The population attributable fraction of severe malaria cases to MBL2*C heterozygosity was estimated to be 17%. Similar findings were obtained in a recent study to assess MBL2 haplotypes in 262 Gabonese malaria patients, where haplotypes associated with low MBL levels were significantly more often found in children with severe malaria [90]. Interestingly, the authors measured a combination of cytokines at admission and showed that plasma MBL levels at admission correlated negatively with proinflammatory cytokine/chemokines. By contrast, a different study investigating several SNPs in Gabonese children with asymptomatic malaria did not find a significant association with MBL2 variants [91]. Garred et al. investigated MBL variant alleles in 551 children from Ghana in relation to Plasmodium falciparum. No difference in MBL genotype frequency was observed between infected and noninfected children in their study. However, they observed significantly higher parasite counts and lower blood glucose levels in patients who were homozygous for MBL variant alleles [92].

These data indicate that MBL may act as disease modifier, but the precise mechanisms need to be elucidated. Although most of the cases reported in bacterial infections have been related with an MBL deficiency, the case of intracellular protozoan seems to be different. In Leishmania [76], the infection to macrophages could be increased by opsonisation. Moreover, Santos et al. [93], in a case-control study, reinforce the concept to show that an epidemical Brazilian population with visceral leishmaniasis contains high MBL serum levels. Analyzing the genetic background of the population, mutant alleles with low MBL production were associated with protected patients. A recent study [94] showed that in the same region a population with high-producing MBL genotypes were associated with an increased risk of severe visceral leishmaniasis.

These findings were reproduced by a recent study in an Azerbaijan population in which alleles associated with high MBL levels were found more frequently in patients with visceral leishmaniasis compared to healthy controls (P = 0.03) [95]. Other examples of protozoa and in particular of Trypanosomatids family indicate contradictory results compared with the MBL/MASP-2 serum levels in Chagas disease patients. High levels of MBL were associated with severe cardiomyopathy, probably because of the proinflammatory activities of MBL [96]. However, another recent study [97] showed a higher presence of low-producing MASP-2 genotypes in patients with cardiomyopathy in chronic Chagas disease. We have included a table with the deficiencies associated with complement factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical complications associated with complement deficiencies. A clear decrease at the serum levels or complete absence of complement factors or complement regulatory proteins alter the different complement pathways.Several clinical complications are summarized including the complement pathway involved, the deficient complement factor and the clinical manifestation associated.

| Clinical situation | Principle of anticomplement therapy | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Glomerulonephritis | C5 inhibition | Eculizumab |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | Replacement of deficient complement inhibitor molecule C5 inhibition |

Recombinant soluble CD59 Eculizumab (monoclonal antibody) |

| Ebola, Hendra viruses | Lectin pathway activation | Chimeric lectins |

| acute myocardial infarction treated with angioplasty or thrombolysis |

C5 inhibition | Pexelizumab (monoclonal antibody) |

| Cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass | Augmentation of complement inhibitory | TP10 (recombinant soluble complement receptor 1) |

| Cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass |

Inhibition of the complement system at many levels |

Heparin |

| Chemotherapy induced neutropenia Erythema multiforme |

MBL (lectin pathway, inflammation) | MBL |

| African trypanosomiasis | Inhibit coat inhibitory of complement activation | Nanobodies |

| Inflammation | Blocking complement activation | An 11 amino acid peptide derived from the parasite complement C2 receptor CRIT, called H17, reduced immune complex-mediated inflammation |

6.2. Ficolins

Contrary to the large number of studies that investigates MBL geno- and phenotype in different clinical settings, the role of the closely related ficolins remains largely unknown. M-ficolin, the only lectin pathway member produced by leukocytes and not by hepatocytes, was only recently discovered to be present in significant amounts in human serum [21, 98]. M-ficolin serum concentrations may reflect phagocyte activation in the course of infection [41], but substantial research is necessary to understand this pattern recognition receptor fully.

H-ficolin deficiency is extremely rare. Two reports [99, 100] described the occurrence of the deficiency in a patient with repeated infections and in a neonate with necrotizing enterocolitis, respectively. Moreover, increased infections with gram + have been associated with neonates with lower H-ficolin serum levels [101].

This year, some clinical data have been associated with L-ficolin deficiency and parasite infections. Ouf et al. [102] showed that ficolin-2 (l-ficolin) levels and FCN2 genetic polymorphism could be important as a susceptibility factor in schistosomosis. In Leishmaniosis [103], some evidence indicated a haplotype of ficolin-2 with susceptibility factor.

A later study that assessed ficolin SNPs in a larger population-based cohort did not find a correlation with recurrent respiratory infections [104]. Recently, Kilpatrick et al. showed lower L-ficolin concentrations in patients with bronchiectasis compared to healthy blood donors [105]. Several studies that investigated L-ficolin levels or genotype in patients with bacterial infections failed to show an association [101, 106, 107]. Specific FCN2 haplotypes associated with normal L-ficolin levels seemed to be protective against clinical leprosy [108]. Faik et al. [109] measured FNC2, SNPs, and L-ficolin level in the same Gabon cohort of 238 children with malaria, they have previously reported on MBL deficiency. Median L-ficolin concentration was higher at admission in the severe malaria cases compared to mild cases. The result was possibly related to the strong immune stimulation during acute disease. No difference in FCN2 haplotypes was found. Apart from this study, no human study data are currently available on ficolins in parasitic infections.

6.3. MASPs

Relatively few studies investigated MASP-2 deficiency. Stengaard-Pedersen et al. [110] described a patient with chronic inflammatory diseases and recurrent pneumococcal pneumonia who was found to suffer from genetically determined MASP-2 deficiency. Two subsequent studies have shown increased incidence of chemotherapy-related infections in MASP-2 deficient patients [111, 112].

Recently, Boldt et al. [97] analyzed six MASP-2 polymorphisms in 208 patients with chronic Chagas disease and 300 healthy individuals from Southern Brazil. They reported that MASP2*CD genotypes, which mostly resulted in low MASP-2 levels, are associated with a high risk of Chagasic cardiomyopathy. They suggested that MASP-2 genotyping might be useful to predict symptomatic Chagas disease.

7. Complement System-Based Therapeutics

7.1. Strategies to Control the Pathogenic Infection

7.1.1. MBL

Based on the first observations of the deleterious effects of MBL deficiency, the potential of MBL as a therapeutic drug has been raised more than a decade ago [113, 114]. Similarly, MBL replacement could represent an interesting therapeutic approach to control parasitic infections in patients with defects in lectin pathway activation. MBL replacement therapy was performed for the first time in a patient with recurrent erythema multiforme, in which fresh frozen plasma containing MBL resulted in clinical improvement of the patient [115]. Subsequently, a phase I safety and pharmacokinetic trial on 20 MBL deficient adult healthy volunteers was performed. No adverse clinical or laboratory effects during or after administration were observed [116]. Later, Petersen et al. [117] reported on a placebo-controlled double blind study on recombinant human MBL replacement. Again, no serious adverse events were recorded, and rhMBL half-life was estimated at 30 h. The first trial (phase II study) on MBL replacement in clinical patients was conducted in MBL deficient children with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia [118]. The children received one to two plasma-derived MBL infusions per week during neutropenia, to aim at levels above 1000 ng/mL, which were shown to restore MBL-mediated complement activation [119]. This study confirmed the feasibility and safety of MBL replacement. Based on these data, further trials on MBL replacement are awaited.

7.1.2. Chimeric Lectins

The production of new chimeric proteins is a novel strategy described by Hartshorn et al. [120]. The authors showed that chimeric proteins contain complementary portions of two collectins (MBL, surfactant protein D, or bovine serum conglutinin) or one collection (surfact protein D) fused to anti-CD89 (an anti Fc-α RI). This chimera increases the antimicrobial and opsonic properties compared with the parent collection

The generation of three RCLs consisting of L-FCN and MBL, in which various lengths of the collagenous domain of MBL were replaced with those of L-FCN [23]. MBL-CRD has broader target recognition than L-FCN, which preferentially recognizes acetylated compounds [44]. These results support our recent findings that these RCLs have better binding activity against Ebola, Nipah, and Hendra viruses [23]. These results demonstrate that novel RCLs are better than rMBL as potent antiviral drugs.

7.1.3. Nanobodies

Understanding the mechanisms of parasite immune evasion has also been proven valuable toward the developments of new therapeutics. The African trypanosome T. brucei persists within the bloodstream of the mammalian host through antigenic variation of the VSG coat. Consequently, anti-VSG antibodies are incapable to kill the parasites in vivo. However, the 15 kDa nanobodies (Nb) derived from camelid heavy-chain antibodies (HCAbs) that recognize variant-specific VSG epitopes can efficiently lyse trypanosomes both in vitro and in vivo [121]. Nanobodies-mediated lysis of trypanosomes results in the enlargement of the parasite flagellar pocket, blockade of endocytosis, and severe metabolic perturbations culminating in cell death. The generation of low molecular weight VSG-specific trypanolytic nanobodies offers a new opportunity to develop novel trypanosomiasis therapeutics.

7.1.4. Peptides

Parasite-derived complement receptors have also been proposed to control complement-mediated host damage. An 11 amino acid peptide derived from the parasite complement C2 receptor CRIT, called H17, was shown to reduce immune complex-mediated inflammation (dermal reversed passive Arthus reaction) in mice, in vivo [122]. Upon the intradermal injection of CRIT-H17, a 41% reduction in oedema and haemorrhage, a 72% reduction in neutrophil influx, and a reduced C3 deposition were observed. Furthermore, administration of intravenous H17 at a 1 mg/kg dose led to reduced inflammation by 31%, to demonstrate that CRIT-H17 is a potential therapeutic agent against complement-mediated inflammatory tissue destruction [122].

7.2. Strategies Used in Other Clinical States

The idea to use complement inhibition as therapy for various diseases and conditions, such as organ transplantation, ischemia-reperfusion injury, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, immunosuppression, paroxysmal nocturnal hematuria, glomerulonephritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, was reviewed recently [123].

Most of the principles of anticomplement therapy are based on the C5 inhibition [124], the replacement of deficient complement inhibitor molecule CD 59 [125], and the augment of complement inhibitory molecules [126].

We have summarized all the strategies from Sections 7.1 and 7.2 in Table 2.

Table 2.

Complement system-based therapeutics. The clinical situation, principle of anticomplement therapy, and complement-based treatment are detailed.

| Complement Deficiencies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement pathways involved | Protein | Associated gene | Complications | ||

| Alternative | Lectin | Classical | |||

| Activation | |||||

| Recognition protein | |||||

|

| |||||

| X | MBL | MBL2 | Infection in immunocompromised patient | ||

| X | H-ficolin | FCN3 | Immune deficiency, necrotizing enterocolitis |

||

| X | C1q | C1QA, C1QB, C1QC | SLE-like syndrome, recurrent bacterial infections |

||

| X |

MASP-2 | MASP-2 | Immune deficiency | ||

| X | C1r/s | C1R, C1S | SLE-like syndrome, recurrent bacterial infections |

||

| X | X | C2 | C2 | Autoimmune disease |

|

| X | Factor D | CFD | Meningococcal and encapsulated bacterial infections | ||

| X | Factor I | CFI | Encapsulated bacterial infections |

||

|

| |||||

| Common Pathways | |||||

| Structural protein | |||||

|

| |||||

| X | X | X | C3 | C3 | Bacterial infections, SLE-like syndrome |

| X | X | X | C4 | C4A, C4B | SLE- like syndrome, encapsulated bacterial infections |

| X | X | X | C5 | C5 | Meningococcal infection |

| X | X | X | C6 | C6 | Meningococcal infection |

| X | X | X | C7 | C7 | Meningococcal infection |

| X | X | X | C8 | C8A, C8B, C8G | Meningococcal infection |

| X | X | X | C9 | C9 | Meningococcal infection |

|

| |||||

| Regulatory proteins | |||||

| Control protein as | |||||

|

| |||||

| X | Properdin | CFP | Meningococcal infection | ||

| Factor H | CFH | Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), dense deposit disease | |||

| CD11a (LFA-1), CD11b (CR3), CD11c (CR4)/CD18' | ITGAL, ITGAM, ITGAX, ITGB2 | Leucocyte adhesion deficiency type I ( LAD I) | |||

| CD46 (MCP) | CD46 | Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) |

|||

8. Conclusion

Understanding pathogen and host interaction is a key aspect in the development of new therapeutics against infectious diseases. Although many things remain to be investigated on the molecular basis of parasitic infection, the current knowledge in complement system highlights the importance of the lectin pathway as a key mediator of host defense against parasitic infections and its potential for a therapeutic target in the control of infection. Some reports have pointed out the importance of the activation of CLP in protozoa, to show that MBL and ficolins require seconds to activate the complement cascade. Probably, the MBL and ficolins present in large quantities in normal human serum guarantee an efficient pathway activation of lectins. However, two aspects are surprising: the extreme diversity of evasion mechanisms deployed by the parasites to produce infection and the high frequency of genetic deficiencies in MBL and complement factors. Although complement-based therapies are promising in some specific clinical states [123], they require a more comprehensive understanding on the characteristics of activation and resistance to each model in infectious diseases to formulate a treatment. For example, for Neisseria spp. and Leishmania spp. [76], the complement factors might be opsonising. Providing input to the parasitic invasion into eukaryotic cells is contradictory to the MBL-ficolin chimeras that block virus entry to eukaryotic cells [125]. More detailed knowledge on early complement activation, development of specific inhibitors, and trials on human population should be next steps to block the pathogen invasion to avoid infection. Therapies to compensate factor deficiencies are welcome when the case is studied carefully.

The complement system could be the central point to control the protozoa, and new chemotherapeutic alternatives should improve the current situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Programa de Parasitologia Basica/CAPES. I. Evans-Osses is a recipient of CAPES Fellowship and M. I. Ramirez is a CNPq fellow.

References

- 1.Garlatti V, Belloy N, Martin L, et al. Structural insights into the innate immune recognition specificities of L- and H-ficolins. EMBO Journal. 2007;26(2):623–633. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krarup A, Mitchell DA, Sim RB. Recognition of acetylated oligosaccharides by human L-ficolin. Immunology Letters. 2008;118(2):152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsushita M, Kuraya M, Hamasaki N, Tsujimura M, Shiraki H, Fujita T. Activation of the lectin complement pathway by H-ficolin (Hakata antigen) Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(7):3502–3506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Runza VL, Schwaeble W, Männel DN. Ficolins: novel pattern recognition molecules of the innate immune response. Immunobiology. 2008;213(3-4):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vorup-Jensen T, Petersen SV, Hansen AG, et al. Distinct pathways of mannan-binding lectin (MBL)- and C1-complex auatoactivation revealed by reconstitution of MBL with recombinant MBL- associated serine protease-2. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(4):2093–2100. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsushita M, Endo Y, Fujita T. Cutting edge: complement-activating complex of ficolin and mannose- binding lectin-associated serine protease. Journal of Immunology. 2000;164(5):2281–2284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stover CM, Thiel S, Thelen M, et al. Two constituents of the initiation complex of the mannan-binding lectin activation pathway of complement are encoded by a single structural gene. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(6):3481–3490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weis WI, Drickamer K, Hendrickson WA. Structure of a C-type mannose-binding protein complexed with an oligosaccharide. Nature. 1992;360(6400):127–134. doi: 10.1038/360127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong M, Sim RB. Comparison of the complement system protein complexes formed by Clq and MBL. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1997;25(1):p. 41. doi: 10.1042/bst025041s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quesenberry MS, Drickamer K. Determination of the minimum carbohydrate-recognition domain in two C-type animal lectins. Glycobiology. 1991;1(6):615–621. doi: 10.1093/glycob/1.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quesenberry MS, Drickamer K. Role of conserved and nonconserved residues in the Ca2+-dependent carbohydrate-recognition domain of a rat mannose-binding protein. Analysis by random cassette mutagenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(15):10831–10841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai T, Kase T, Suzuki Y, et al. Anti-influenza A virus activities of mannan-binding lectins and bovine conglutinin. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 2007;69(2):221–224. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack DL, Jarvis GA, Booth CL, Turner MW, Klein NJ. Mannose-binding lectin accelerates complement activation and increases serum killing of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;184(7):836–845. doi: 10.1086/323204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cestari IDS, Krarup A, Sim RB, Inal JM, Ramirez MI. Role of early lectin pathway activation in the complement-mediated killing of Trypanosoma cruzi . Molecular Immunology. 2009;47(2-3):426–437. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmberg V, Schuster F, Dietz E, et al. Mannose-binding lectin variant associated with severe malaria in young African children. Microbes and Infection. 2008;10(4):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu J, Le Y, Kon OL, Chan J, Lee SH. Biosynthesis of human ficolin, and Escherichia coli-binding protein, by monocytes: comparison with the synthesis of two macrophage-specific proteins, C1q and the mannose receptor. Immunology. 1996;89(2):289–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harumiya S, Takeda K, Sugiura T, et al. Characterization of ficolins as novel elastin-binding proteins and molecular cloning of human ficolin-1. Journal of Biochemistry. 1996;120(4):745–751. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endo Y, Sato Y, Matsushita M, Fujita T. Cloning and characterization of the human lectin P35 gene and its related gene. Genomics. 1996;36(3):515–521. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsushita M, Endo Y, Taira S, et al. A novel human serum lectin with collagen- and fibrinogen-like domains that functions as an opsonin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(5):2448–2454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Y, Lee SH, Kon OL, Lu J. Human L-ficolin: plasma levels, sugar specificity, and assignment of its lectin activity to the fibrinogen-like (FBG) domain. FEBS Letters. 1998;425(2):367–370. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittenborn T, Thiel S, Jensen L, Nielsen HJ, Jensenius JC. Characteristics and biological variations of M-ficolin, a pattern recognition molecule, in plasma. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2010;2(2):167–180. doi: 10.1159/000218324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hummelshoj T, Thielens NM, Madsen HO, Arlaud GJ, Sim RB, Garred P. Molecular organization of human Ficolin-2. Molecular Immunology. 2007;44(4):401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohashi T, Erickson HP. The disulfide bonding pattern in ficolin multimers. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(8):6534–6539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanio M, Kondo S, Sugio S, Kohno T. Trivalent recognition unit of innate immunity system: crystal structure of trimeric human M-ficolin fibrinogen-like domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(6):3889–3895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Endo Y, Iwaki D, et al. Human M-ficolin is a secretory protein that activates the lectin complement pathway. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(5):3150–3156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krarup A, Thiel S, Hansen A, Fujita T, Jensenius JC. L-ficolin is a pattern recognition molecule specific for acetyl groups. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(46):47513–47519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohashi T, Erickson HP. Oligomeric structure and tissue distribution of ficolins from mouse, pig and human. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1998;360(2):223–232. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch NJ, Roscher S, Hartung T, et al. L-ficolin specifically binds to lipoteichoic acid, a cell wall constituent of Gram-positive bacteria, and activates the lectin pathway of complement. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(2):1198–1202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nahid AM, Sugii S. Binding of porcine ficolin-α to lipopolysaccharides from Gram-negative bacteria and lipoteichoic acids from Gram-positive bacteria. Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 2006;30(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Ali MAM, Shi Y, et al. Specifically binding of L-ficolin to N-glycans of HCV envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 leads to complement activation. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 2009;6(4):235–244. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma YG, Cho MY, Zhao M, et al. Human mannose-binding lectin and L-ficolin function as specific pattern recognition proteins in the lectin activation pathway of complement. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(24):25307–25312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuraya M, Matsushita M, Endo Y, Thiel S, Fujita T. Expression of H-ficolin/Hakata antigen, mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease (MASP)-1 and MASP-3 by human glioma cell line T98G. International Immunology. 2003;15(1):109–117. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohashi T, Erickson HP. Two oligomeric forms of plasma ficolin have differential lectin activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(22):14220–14226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gout E, Garlatti V, Smith DF, et al. Carbohydrate recognition properties of human ficolins: glycan array screening reveals the sialic acid binding specificity of M-ficolin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(9):6612–6622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swierzko A, Lukasiewicz J, Cedzynski M, et al. New functional ligands for ficolin-3 among lipopolysaccharides of Hafnia alvei . Glycobiology. 2012;22(2):267–280. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teh C, Le Y, Lee SH, Lu J. M-ficolin is expressed on monocytes and is a lectin binding to N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and mediates monocyte adhesion and phagocytosis of Escherichia coli . Immunology. 2000;101(2):225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honoré C, Rørvig S, Munthe-Fog L, et al. The innate pattern recognition molecule Ficolin-1 is secreted by monocytes/macrophages and is circulating in human plasma. Molecular Immunology. 2008;45(10):2782–2789. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garlatti V, Martin L, Gout E, et al. Structural basis for innate immune sensing by M-ficolin and its control by a pH-dependent conformational switch. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(49):35814–35820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frederiksen PD, Thiel S, Larsen CB, Jensenius JC. M-ficolin, an innate immune defence molecule, binds patterns of acetyl groups and activates complement. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2005;62(5):462–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanio M, Wakamatsu K, Kohno T. Binding site of C-reactive protein on M-ficolin. Molecular Immunology. 2009;47(2-3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kjaer TR, Hansen AG, Sørensen UBS, Nielsen O, Thiel S, Jensenius JC. Investigations on the pattern recognition molecule M-ficolin: quantitative aspects of bacterial binding and leukocyte association. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2011;90(3):425–437. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0411201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feinberg H, Uitdehaag JCM, Davies JM, Wallis R, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Crystal structure of the CUB1-EGF-CUB2 region of mannose-binding protein associated serine protease-2. EMBO Journal. 2003;22(10):2348–2359. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi V, Bally I, Thielens NM, Esser AF, Arlaud GJ. Baculovirus-mediated expression of truncated modular fragments from the catalytic region of human complement serine protease C1s. Evidence for the involvement of both complement control protein modules in the recognition of the C4 protein substrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(2):1232–1239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallis R, Dodd RB. Interaction of mannose-binding protein with associated serine proteases. Effects of naturally occurring mutations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(40):30962–30969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiel S, Vorup-Jensen T, Stover CM, et al. A second serine protease associated with mannan-binding lectin that activates complement. Nature. 1997;386(6624):506–510. doi: 10.1038/386506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Presanis JS, Hajela K, Ambrus G, Gál P, Sim RB. Differential substrate and inhibitor profiles for human MASP-1 and MASP-2. Molecular Immunology. 2004;40(13):921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ambrus G, Gál P, Kojima M, et al. Natural substrates and inhibitors of mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-1 and -2: a study on recombinant catalytic fragments. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(3):1374–1382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi M, Iwaki D, Kanno K, et al. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL)-associated serine protease (MASP)-1 contributes to activation of the lectin complement pathway. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(9):6132–6138. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skjoedt MO, Hummelshoj T, Palarasah Y, et al. A novel mannose-binding lectin/ficolin-associated protein is highly expressed in heart and skeletal muscle tissues and inhibits complement activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(11):8234–8243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lambris JD, Ricklin D, Geisbrecht BV. Complement evasion by human pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6(2):132–142. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ambrosio AR, De Messias-Reason IJT. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis: interaction of mannose-binding lectin with surface glycoconjugates and complement activation. An antibody-independent defence mechanism. Parasite Immunology. 2005;27(9):333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans-Osses I, Ansa-Addo EA, Inal JM, Ramirez MI. Involvement of lectin pathway activation in the complement killing of Giardia intestinalis . Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;395(3):382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green PJ, Feizi T, Stoll MS, Thiel S, Prescott A, McConville MJ. Recognition of the major cell surface glycoconjugates of Leishmania parasites by the human serum mannan-binding protein. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1994;66(2):319–328. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cestari I, Ramirez MI. Inefficient complement system clearance of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes enables resistant strains to invade eukaryotic cells. PloS One. 2010;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009721.e9721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida N, Araguth MF. Trypanolytic activity and antibodies to metacyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi in non-Chagasic human sera. Parasite Immunology. 1987;9(3):389–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1987.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Almeida IC, Ferguson MAJ, Schenkman S, Travassos LR. Lytic anti-α-galactosyl antibodies from patients with chronic Chagas’ disease recognize novel O-linked oligosaccharides on mucin-like glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoproteins of Trypanosoma cruzi . Biochemical Journal. 1994;304(3):793–802. doi: 10.1042/bj3040793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almeida IC, Milani SR, Gorin PAJ, Travassos LR. Complement-mediated lysis of Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes by human anti-α-galactosyl antibodies. Journal of Immunology. 1991;146(7):2394–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Suter DM, et al. Human serum IgM glycosylation: identification of glycoforms that can bind to Mannan-binding lectin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(32):29080–29087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malhotra R, Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Fischer PB, Dwek RA, Sim RB. Glycosylation changes of IgG associated with rheumatoid arthritis can activate complement via the mannose-binding protein. Nature Medicine. 1995;1(3):237–243. doi: 10.1038/nm0395-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roos A, Bouwman LH, Van Gijlswijk-Janssen DJ, Faber-Krol MC, Stahl GL, Daha MR. Human IgA activates the complement system via the Mannan-Binding lectin pathway. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(5):2861–2868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cestari IDS, Evans-Osses I, Freitas JC, Inal JM, Ramirez MI. Complement C2 receptor inhibitor trispanning confers an increased ability to resist complement-mediated lysis in Trypanosoma cruzi . Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;198(9):1276–1283. doi: 10.1086/592167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Domínguez M, Moreno I, López-Trascasa M, Toraño A. Complement interaction with trypanosomatid promastigotes in normal human serum. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;195(4):451–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joiner K, Sher A, Gaither T, Hammer C. Evasion of alternative complement pathway by Trypanosoma cruzi results from inefficient binding of factor B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(17):6593–6597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moreno I, Molina R, Toraño A, Laurin E, García E, Domínguez M. Comparative real-time kinetic analysis of human complement killing of Leishmania infantum promastigotes derived from axenic culture or from Phlebotomus perniciosus . Microbes and Infection. 2007;9(14-15):1574–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stoermer KA, Morrison TE. Complement and viral pathogenesis. Virology. 2011;411(2):362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cestari I, Ansa-Addo E, Deolindo P, Inal JM, Ramirez MI. Trypanosoma cruzi immune evasion mediated by host cell-derived microvesicles. Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(4):1942–1952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norris KA. Stable transfection of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes with the trypomastigote-specific complement regulatory protein cDNA confers complement resistance. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66(6):2460–2465. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2460-2465.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Norris KA, Harth G, So M. Purification of a Trypanosoma cruzi membrane glycoprotein which elicits lytic antibodies. Infection and Immunity. 1989;57(8):2372–2377. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2372-2377.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferreira V, Molina MC, Valck C, et al. Role of calreticulin from parasites in its interaction with vertebrate hosts. Molecular Immunology. 2004;40(17):1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferreira V, Valck C, Sánchez G, et al. The classical activation pathway of the human complement system is specifically inhibited by calreticulin from Trypanosoma cruzi . Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(5):3042–3050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramírez G, Valck C, Molina MC, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi calreticulin: a novel virulence factor that binds complement C1 on the parasite surface and promotes infectivity. Immunobiology. 2011;216(1-2):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Valck C, Ramírez G, López N, et al. Molecular mechanisms involved in the inactivation of the first component of human complement by Trypanosoma cruzi calreticulin. Molecular Immunology. 2010;47(7-8):1516–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tambourgi DV, Kipnis TL, Da Silva WD, et al. A partial cDNA clone of trypomastigote decay-accelerating factor (T-DAF), a developmentally regulated complement inhibitor of Trypanosoma cruzi, has genetic and functional similarities to the human complement inhibitor DAF. Infection and Immunity. 1993;61(9):3656–3663. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3656-3663.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fischer E, Ouaissi MA, Velge P, Cornette J, Kazatchkine MD. Gp 58/68, a parasite component that contributes to the escape of the trypomastigote form of T. cruzi from damage by the human alternative complement pathway. Immunology. 1988;65(2):299–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Russell DG. The macrophage-attachment glycoprotein gp63 is the predominant C3-acceptor site on Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1987;164(1):213–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brittingham A, Morrison CJ, McMaster WR, McGwire BS, Chang KP, Mosser DM. Role of the Leishmania surface protease gp63 in complement fixation, cell adhesion, and resistance to complement-mediated lysis. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(6):3102–3111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Späth GF, Epstein L, Leader B, et al. Lipophosphoglycan is a virulence factor distinct from related glycoconjugates in the protozoan parasite Leishmania major . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(16):9258–9263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160257897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Puentes SM, Da Silva RP, Sacks DL, Hammer CH, Joiner KA. Serum resistance of metacyclic stage Leishmania major promastigotes is due to release of C5b-9. Journal of Immunology. 1990;145(12):4311–4316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russo DCW, Williams DJL, Grab DJ. Mechanisms for the elimination of potentially lytic complement-fixing variable surface glycoprotein antibody-complexes in Trypanosoma brucei . Parasitology Research. 1994;80(6):487–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00932695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Engstler M, Pfohl T, Herminghaus S, et al. Hydrodynamic flow-mediated protein sorting on the cell surface of Trypanosomes. Cell. 2007;131(3):505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rudenko G. African trypanosomes: the genome and adaptations for immune evasion. Essays in Biochemistry. 2011;51:47–62. doi: 10.1042/bse0510047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deng J, Gold D, LoVerde PT, Fishelson Z. Inhibition of the complement membrane attack complex by Schistosoma mansoni paramyosin. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71(11):6402–6410. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6402-6410.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deng J, Gold D, LoVerde PT, Fishelson Z. Mapping of the complement C9 binding domain in paramyosin of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni . International Journal for Parasitology. 2007;37(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Inal JM, Sim RB. A Schistosoma protein, Sh-TOR, is a novel inhibitor of complement which binds human C2. FEBS Letters. 2000;470(2):131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Inal JM. Schistosoma TOR (trispanning orphan receptor), a novel, antigenic surface receptor of the blood-dwelling, Schistosoma parasite. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1445(3):283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inal JM, Schifferli JA. Complement C2 receptor inhibitor trispanning and the β-chain of C4 share a binding site for complement C2. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(10):5213–5221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Horta MFM, Ramalho-Pinto FJ. Role of human decay-accelerating factor in the evasion of Schistosoma mansoni from the complement-mediated killing in vitro. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1991;174(6):1399–1406. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frevert U, Schenkman S, Nussenzweig V. Stage-specific expression and intracellular shedding of the cell surface trans-sialidase of Trypanosoma cruzi . Infection and Immunity. 1992;60(6):2349–2360. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2349-2360.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Luty AJF, Kun JFJ, Kremsner PG. Mannose-binding lectin plasma levels and gene polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;178(4):1221–1224. doi: 10.1086/515690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Boldt ABW, Luty A, Grobusch MP, et al. Association of a new mannose-binding lectin variant with severe malaria in Gabonese children. Genes and Immunity. 2006;7(5):393–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mombo LE, Lu CY, Ossari S, et al. Mannose-binding lectin alleles in sub-Saharan Africans and relation with susceptibility to infections. Genes and Immunity. 2003;4(5):362–367. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garred P, Larsen F, Madsen HO, Koch C. Mannose-binding lectin deficiency—revisited. Molecular Immunology. 2003;40(2–4):73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(03)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Miranda Santos IKF, Costa CHN, Krieger H, et al. Mannan-binding lectin enhances susceptibility to visceral leishmaniasis. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69(8):5212–5215. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.5212-5215.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alonso DP, Ferreira AFB, Ribolla PEM, et al. Genotypes of the mannan-binding lectin gene and susceptibility to visceral leishmaniasis and clinical complications. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;195(8):1212–1217. doi: 10.1086/512683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Asgharzadeh M, Mazloumi A, Kafil HS, Ghazanchaei A. Mannose-binding lectin gene and promoter polymorphism in visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum . Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 2007;10(11):1850–1854. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.1850.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Luz PR, Miyazaki MI, Neto NC, Nisihara RM, Messias-Reason IJ. High levels of mannose-binding lectin are associated with the risk of severe cardiomyopathy in chronic Chagas Disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2010;143(3):448–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boldt ABW, Luz PR, Messias-Reason IJT. MASP2 haplotypes are associated with high risk of cardiomyopathy in chronic Chagas disease. Clinical Immunology. 2011;140(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sallenbach S, Thiel S, Aebi C, et al. Serum concentrations of lectin-pathway components in healthy neonates, children and adults: mannan-binding lectin (MBL), M-, L-, and H-ficolin, and MBL-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2) Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2011;22(4):424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Munthe-Fog L, Hummelshøj T, Honoré C, Madsen HO, Permin H, Garred P. Immunodeficiency associated with FCN3 mutation and ficolin-3 deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(25):2637–2644. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schlapbach LJ, Thiel S, Kessler U, Ammann RA, Aebi C, Jensenius JC. Congenital H-ficolin deficiency in premature infants with severe necrotising enterocolitis. Gut. 2011;60(10):1438–1439. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schlapbach LJ, Mattmann M, Thiel S, et al. Differential role of the lectin pathway of complement activation in susceptibility to neonatal sepsis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;51(2):153–162. doi: 10.1086/653531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ouf EA, Ojurongbe O, Akindele AA, et al. Ficolin-2 levels and FCN2 genetic polymorphisms as a susceptibility factor in schistosomiasis. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;206(4):562–570. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Assaf A, van Hoang T, Faik I, et al. Genetic evidence of functional ficolin-2 haplotype as susceptibility factor in cutaneous leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034113.e34113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ruskamp JM, Hoekstra MO, Postma DS, et al. Exploring the role of polymorphisms in ficolin genes in respiratory tract infections in children. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2009;155(3):433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kilpatrick DC, Chalmers JD, MacDonald SL, et al. Stable bronchiectasis is associated with low serum L-ficolin concentrations. Clinical Respiratory Journal. 2009;3(1):29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chapman SJ, Vannberg FO, Khor CC, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the FCN2 gene are not associated with invasive pneumococcal disease. Molecular Immunology. 2007;44(12):3267–3270. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kilpatrick DC, Mclintock LA, Allan EK, et al. No strong relationship between mannan binding lectin or plasma ficolins and chemotherapy-related infections. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2003;134(2):279–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.De Messias-Reason I, Kremsner PG, Kun JFJ. Functional haplotypes that produce normal ficolin-2 levels protect against clinical leprosy. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;199(6):801–804. doi: 10.1086/597070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Faik I, Oyedeji SI, Idris Z, et al. Ficolin-2 levels and genetic polymorphisms of FCN2 in malaria. Human Immunology. 2011;72(1):74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stengaard-Pedersen K, Thiel S, Gadjeva M, et al. Inherited deficiency of mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(6):554–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schlapbach LJ, Aebi C, Otth M, Leibundgut K, Hirt A, Ammann RA. Deficiency of mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 associated with increased risk of fever and neutropenia in pediatric cancer patients. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2007;26(11):989–994. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31811ffe6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Granell M, Urbano-Ispizua A, Suarez B, et al. Mannan-binding lectin pathway deficiencies and invasive fungal infections following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34(10):1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Neth O, Hann I, Turner MW, Klein NJ. Deficiency of mannose-binding lectin and burden of infection in children with malignancy: a prospective study. The Lancet. 2001;358(9282):614–618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Summerfield JA. Clinical potential of mannose-binding lectin-replacement therapy. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2003;31(4):770–773. doi: 10.1042/bst0310770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Valdimarsson H. Infusion of plasma-derived mannan-binding lectin (MBL) into MBL-deficient humans. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2003;31(4):768–769. doi: 10.1042/bst0310768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Valdimarsson H, Vikingsdottir T, Bang P, et al. Human plasma-derived mannose-binding lectin: a phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2004;59(1):97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Petersen KA, Matthiesen F, Agger T, et al. Phase I safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic study of recombinant human mannan-binding lectin. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2006;26(5):465–475. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-9037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brouwer N, Frakking FNJ, Van De Wetering MD, et al. Mannose-Binding Lectin (MBL) substitution: recovery of opsonic function in vivo lags behind MBL serum levels. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(5):3496–3504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Frakking FNJ, Brouwer N, van de Wetering MD, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of plasma-derived mannose-binding lectin (MBL) substitution in children with chemotherapy-induced neutropaenia. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45(4):505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hartshorn KL, Sastry KN, Chang D, White MR, Crouch EC. Enhanced anti-influenza activity of a surfactant protein D and serum conglutinin fusion protein. American Journal of Physiology. 2000;278(1):L90–L98. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.1.L90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stijlemans B, Caljon G, Natesan SKA, et al. High affinity nanobodies against the trypanosome brucei VSG are potent trypanolytic agents that block endocytosis. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002072.e1002072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Inal JM, Schneider B, Armanini M, Schifferli JA. A peptide derived from the parasite receptor, complement C2 receptor inhibitor trispanning, suppresses immune complex-mediated inflammation in mice. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(8):4310–4317. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kulkarni PA, Afshar-Kharghan V. Anticomplement therapy. Biologics. 2008;2(4):671–685. doi: 10.2147/btt.s2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Thomas TC, Rollins SA, Rother RP, et al. Inhibition of complement activity by humanized anti-C5 antibody and single-chain Fv. Molecular Immunology. 1996;33(17-18):1389–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(96)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Spitzer D, Unsinger J, Bessler M, Atkinson JP. ScFv-mediated in vivo targeting of DAF to erythrocytes inhibits lysis by complement. Molecular Immunology. 2004;40(13):911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Banz Y, Hess OM, Robson SC, et al. Attenuation of myocardial reperfusion injury in pigs by Mirococept, a membrane-targeted complement inhibitor derived from human CR1. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;76(3):482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]