Abstract

In a recent publication (K. Ishikawa et al., 2008, Science 320, 661–664), the authors described how replacing the endogenous mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in a weakly metastatic mouse tumor cell line with mtDNA from a highly metastatic cell line enhanced tumor progression through enhanced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The authors attributed the transformation from a low-metastatic cell line to a high-metastatic phenotype to overproduction of ROS (hydrogen peroxide and superoxide) caused by a dysfunction in mitochondrial complex I protein encoded by mtDNA transferred from the highly metastatic tumor cell line. In this critical evaluation, using the paper by Ishikawa et al. as an example, we bring to the attention of researchers in the free radical field how the failure to appreciate the complexities of dye chemistry could potentially lead to pitfalls, misinterpretations, and erroneous conclusions concerning ROS involvement. Herein we make a case that the authors have failed to show evidence for formation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, presumed to be generated from complex I deficiency associated with mtDNA mutations in metastatic cells.

Keywords: Reactive oxygen species, Fluorescent probes, Metastasis, Mitochondria, Dichlorodihydrofluorescein, Hydroethidine, Hydrogen peroxide, Superoxide, Free radicals

Recently, Ishikawa et al. [1] reported that the replacement of endogenous mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in a weakly metastatic mouse tumor cell line with the mtDNA derived from a highly metastatic cell line enhanced the progression of tumor mediated by overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), namely superoxide radical anion (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). This transformation from a weakly metastatic tumor cell line to a highly metastatic phenotype was attributed to a dysfunctional mitochondrial complex I encoded by mtDNA transferred from the highly metastatic cells. The overall conclusion was that an overproduction of ROS generated from mitochondrial complex I was responsible for increased tumor cell metastasis. The authors employed the flow cytometry technique using two fluorogenic probes, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH2-DA) and mito-hydroethidine (Mito-HE or MitoSOX red), to quantify the levels of H2O2 and O2•−. In this critical commentary, we point out that the authors [1] have failed to show evidence for the involvement of ROS in the tumor cell transformation owing to a lack of appreciation of the complex radical chemistry of the fluorescent dyes. Our conclusions are supported by the following findings.

Intracellular DCF fluorescence arising from DCFH2-DA cannot be used to quantify intracellular hydrogen peroxide

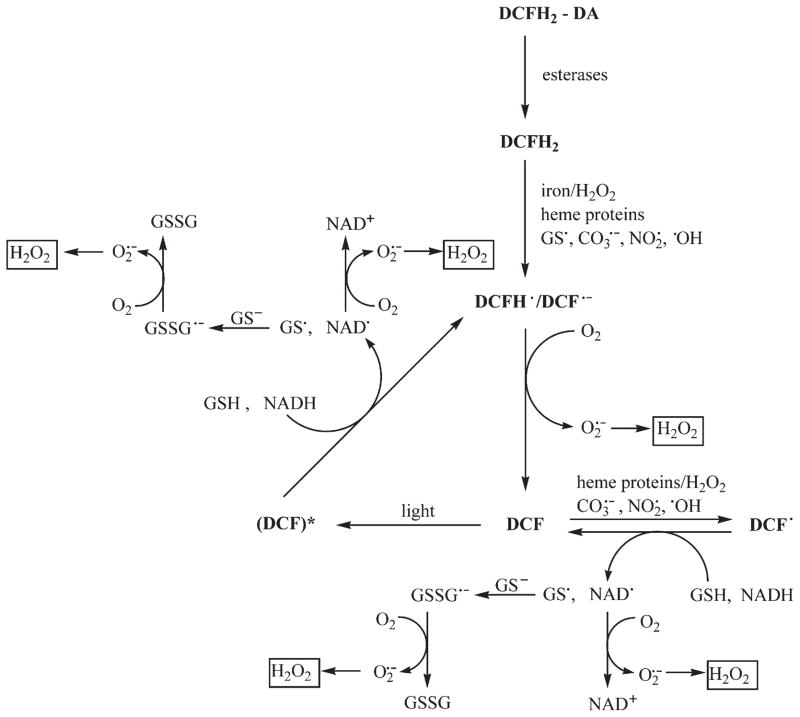

DCFH2-DA is cell-permeative and is taken up into several cell types. DCFH2-DA ester is hydrolyzed inside the cells by esterases, forming DCFH2 (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin). DCFH2 is not strongly fluorescent; however, DCFH2 is oxidized to a green-fluorescent molecule, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF), a two-electron oxidation product of DCFH2. Contrary to common belief, DCFH2 does not readily react with H2O2 to form DCF [2,3]. Trace levels of redox-active metal ions (e.g., ferrous iron or ferric ion and reductants) or heme proteins (cytochrome c or peroxidase) are required to catalyze the conversion of DCFH2 to DCF [2–8]. This is mediated by hydroxyl radicals or iron intermediates of higher oxidation states. In this reaction, DCFH2 is initially oxidized to a radical (DCFH•/DCF•−) that reacts with molecular oxygen to form superoxide that dismutates to form additional hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 1) [3,9–11]. Moreover, the fluorescent product, DCF, can undergo further oxidation to a phenoxyl-type radical as well as acting as a photosensitizer for oxidation of intracellular reductants, such as GSH or NADH, yielding additional superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 1) [12,13]. Clearly, DCFH2 itself can induce intracellular H2O2 formation. Thus, the green fluorescence observed by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry under conditions of intracellular oxidative stress is not a measure of intracellular H2O2 or any other form of intracellular oxidant, but it is the result of combination of several factors including, but not limited to, reduced GSH level, altered iron uptake, increased peroxidase activity, and cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Consequently, the statement “H2O2 formation generated by mtDNA mutations was quantitatively measured by DCFH dye” [1] is incorrect.

Fig. 1.

Intracellular redox chemistry of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH2) [2–13,24,25].

Reaction between superoxide and hydroethidine (HE) or Mito-HE (MitoSOX red) does not result in the formation of ethidium or mito-ethidium

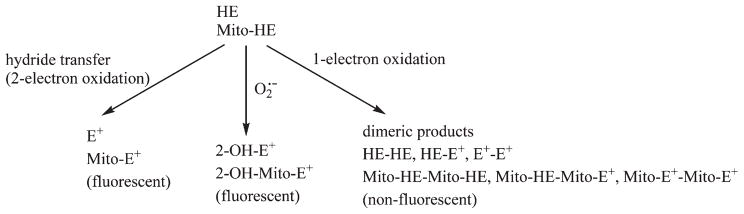

Existing literature data unambiguously show that superoxide/ hydroethidine and superoxide/mito-hydroethidine reactions do not result in the formation of ethidium (E+) or mito-ethidium (Mito-E+) [14–21]. Mito-HE, a triphenylphosphonium-conjugated mitochondria-targeted analog of HE, essentially reacts with superoxide in the same manner as does HE [17,21]. Both HE and Mito-HE react with superoxide at similar rates (k = 2 × 106 M−1 s−1 [17,18]) to form the corresponding hydroxylated products, 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+) and 2-hydroxy-mito-ethidium (2-OH-Mito-E+) (Fig. 2) [14,16,20,21]. The fluorescence parameters of these hydroxylated products are different from those of ethidium and mito-ethidium [14,16,17,20,21]. In their paper, Ishikawa et al. report that the fluorescence spectrum was attributed to ethidium formed from the reaction between MitoSOX (Mito-HE) and superoxide [1]. The notion that superoxide directly oxidizes HE or Mito-HE to the corresponding ethidium or mito-ethidium is erroneous.

Fig. 2.

Redox chemistry of hydroethidine (HE) and its mitochondria-targeted analog (Mito-HE) [14,16–21,26].

Intracellular red fluorescence derived from HE cannot be used to quantitate superoxide formation

Ishikawa et al. state in their Science paper that the red fluorescence derived from Mito-HE is a quantitative measure of intracellular superoxide formation [1]. Both HE and Mito-HE are also oxidatively converted to their ethidium analogs (exhibiting red fluorescence) [15,16,20,21]. The fluorescence spectra of E+ and 2-OH-E+ (2-OH-Mito-E+ and Mito-E+) have a significant overlap and it is nearly impossible to deduce the individual contributions of the superoxide/Mito-HE reaction product (2-OH-Mito-E+) and superoxide-independent product, Mito-E+. Thus, the fluorescence microscopy results obtained from Mito-HE do not give quantitative information on intracellular superoxide levels. In addition, both HE and Mito-HE undergo one-electron (e.g., peroxidatic) oxidation in cells, forming several dimeric products that are not fluorescent (Fig. 2) [20–23]. Even for qualitative estimation of intracellular superoxide, one has to perform an HPLC analysis of cell extracts for the isolation and quantification of the superoxide-specific oxidation product of HE or Mito-HE [15,16,20,21].

Conclusion

In their Science paper, Ishikawa et al. did not appreciate the various methodological pitfalls for detecting ROS in cells using the fluorescent dyes DCFH2-DA and Mito-HE (MitoSOX red). We submit that Ishikawa et al. failed to provide evidence in support of enhanced ROS formation in cells overexpressing mitochondrial DNA mutations derived from metastatic cells and that their paper is one of many papers wherein the fluorescent probes have been used indiscriminately for ROS detection.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grants HL073056, NS039958 and R01HL067244.

References

- 1.Ishikawa K, Takenaga K, Akimoto M, Koshikawa N, Yamaguchi A, Imanishi H, Nakada K, Honma Y, Hayashi J. ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis. Science. 2008;320:661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.1156906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeBel CP, Ischiropoulos H, Bondy SC. Evaluation of the probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin as an indicator of reactive oxygen species formation and oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:227–231. doi: 10.1021/tx00026a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardman P. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for measurement of oxidative and nitrosative species in cells and tissues: progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:995–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkitt MJ, Wardman P. Cytochrome c is a potent catalyst of dichlorofluorescin oxidation: implications for the role of reactive oxygen species in apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:329–333. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohashi T, Mizutani A, Murakami A, Kojo S, Ishii T, Taketani S. Rapid oxidation of dichlorodihydrofluorescin with heme and hemoproteins: formation of the fluorescein is independent of the generation of reactive oxygen species. FEBS Lett. 2002;511:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence A, Jones CM, Wardman P, Burkitt MJ. Evidence for the role of a peroxidase compound I-type intermediate in the oxidation of glutathione, NADH, ascorbate, and dichlorofluorescin by cytochrome c/H2O2: implications for oxidative stress during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29410–29419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tampo Y, Kotamraju S, Chitambar CR, Kalivendi SV, Keszler A, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Oxidative stress-induced iron signaling is responsible for peroxide-dependent oxidation of dichlorodihydrofluorescein in endothelial cells: role of transferrin receptor-dependent iron uptake in apoptosis. Circ Res. 2003;92:56–63. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000048195.15637.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkitt M, Jones C, Lawrence A, Wardman P. Activation of cytochrome c to a peroxidase compound I-type intermediate by H2O2: relevance to redox signalling in apoptosis. Biochem Soc Symp. 2004:97–106. doi: 10.1042/bss0710097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rota C, Chignell CF, Mason RP. Evidence for free radical formation during the oxidation of 2′-7′-dichlorofluorescin to the fluorescent dye 2′-7′-dichlorofluorescein by horseradish peroxidase: possible implications for oxidative stress measurements. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:873–881. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonini MG, Rota C, Tomasi A, Mason RP. The oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin to reactive oxygen species: a self-fulfilling prophesy? Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wrona M, Wardman P. Properties of the radical intermediate obtained on oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein, a probe for oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchesi E, Rota C, Fann YC, Chignell CF, Mason RP. Photoreduction of the fluorescent dye 2′-7′-dichlorofluorescein: a spin trapping and direct electron spin resonance study with implications for oxidative stress measurements. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:148–161. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rota C, Fann YC, Mason RP. Phenoxyl free radical formation during the oxidation of the fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein by horseradish peroxidase: possible consequences for oxidative stress measurements. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28161–28168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao H, Kalivendi S, Zhang H, Joseph J, Nithipatikom K, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Superoxide reacts with hydroethidine but forms a fluorescent product that is distinctly different from ethidium: potential implications in intracellular fluorescence detection of superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink B, Laude K, McCann L, Doughan A, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Detection of intracellular superoxide formation in endothelial cells and intact tissues using dihydroethidium and an HPLC-based assay. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287: C895–C902. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00028.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao H, Joseph J, Fales HM, Sokoloski EA, Levine RL, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Detection and characterization of the product of hydroethidine and intracellular superoxide by HPLC and limitations of fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5727–5732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson KM, Janes MS, Pehar M, Monette JS, Ross MF, Hagen TM, Murphy MP, Beckman JS. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15038–15043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601945103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zielonka J, Sarna T, Roberts JE, Wishart JF, Kalyanaraman B. Pulse radiolysis and steady-state analyses of the reaction between hydroethidine and superoxide and other oxidants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;456:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. The confounding effects of light, sonication, and Mn(III)TBAP on quantitation of superoxide using hydroethidine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Detection of 2-hydroxyethidium in cellular systems: a unique marker product of superoxide and hydroethidine. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:8–21. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zielonka J, Srinivasan S, Hardy M, Ouari O, Lopez M, Vasquez-Vivar J, Avadhani NG, Kalyanaraman B. Cytochrome c-mediated oxidation of hydro-ethidine and mito-hydroethidine in mitochondria: identification of homo- and heterodimers. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papapostolou I, Patsoukis N, Georgiou CD. The fluorescence detection of superoxide radical using hydroethidine could be complicated by the presence of heme proteins. Anal Biochem. 2004;332:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patsoukis N, Papapostolou I, Georgiou CD. Interference of non-specific peroxidases in the fluorescence detection of superoxide radical by hydro-ethidine oxidation: a new assay for H2O2. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;381:1065–1072. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrona M, Patel K, Wardman P. Reactivity of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein and dihydrorhodamine 123 and their oxidized forms toward carbonate, nitrogen dioxide, and hydroxyl radicals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrona M, Patel KB, Wardman P. The roles of thiol-derived radicals in the use of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein as a probe for oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zielonka J, Zhao H, Xu Y, Kalyanaraman B. Mechanistic similarities between oxidation of hydroethidine by Fremy’s salt and superoxide: stopped-flow optical and EPR studies. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]