Abstract

Purpose: Despite advances in therapeutic angiogenesis by bone marrow cell implantation (BMCI), limb amputation remains a major unfavorable outcome in patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI). We sought to identify predictor(s) of limb salvage in CLI patients who received BMCI.

Materials and Methods: Nineteen patients with CLI who treated by BMCI were divided into two groups; four patients with above-the-ankle amputation by 12 weeks after BMCI (amputation group) and the remaining 15 patients without (salvage group). We performed several blood-flow examinations before BMCI. Ankle-brachial index (ABI) was measured with the standard method. Transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2) was measured at the dorsum of the foot, in the absence (baseline) and presence (maximum TcPO2) of oxygen inhalation. 99mtechnetium-tetrofosmin (99mTc-TF) perfusion index was determined at the foot and lower leg as the ratio of brain.

Results: Maximum TcPO2 (p = 0.031) and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot (p = 0.0068) was significantly higher in the salvage group than in the amputation group. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis identified maximum TcPO2 and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot as having high predictive accuracy for limb salvage.

Conclusion: Maximum TcPO2 and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot are promising predictors of limb salvage after BMCI in CLI.

Keywords: critical limb ischemia, bone marrow cell implantation, limb salvage, 99mtechnetium-tetrofosmin perfusion scintigraphy, transcutaneous oxygen tension

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a progressive illness primarily due to atherosclerosis. It also occurs in Buerger’s disease and collagen disease involving vasculitis in small and medium-sized arteries. The most severe manifestation is termed “critical limb ischemia (CLI),” as demonstrated by ischemic rest pain and/or loss of tissue integrity, including skin ulceration and gangrene.1) PAD relates to a worse long-term outcome2); furthermore, only 45% of CLI patients were free from limb amputation or death within a year after diagnosis.1) The current goals of management of CLI are to relieve ischemic pain, heal ischemic ulcers, and prevent major limb amputation, in addition to reducing cardiovascular mortality.

Recent advances in surgical and percutaneous revascularization have led to better treatment options for patients with CLI.3) Notably, revascularization is not suitable in a considerable proportion of patients (10–15%) (“no-option patients”). Of these patients, more than 40% would require a major limb amputation, and 20% would die within 6 months.4) For such “no-option patients,” therapeutic angiogenesis by autologous bone marrow cell implantation (BMCI) has emerged as a novel strategy in an attempt to improve blood perfusion at the ischemic site, and evidence has accumulated that BMCI is a safe and effective treatment for CLI.5,6)

Because the clinical condition of patients with CLI changes with time, repeated blood flow examinations are necessary. Thus, it is important to establish non-invasive and convenient examinations to detect blood flow. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is convenient and the most utilized method to diagnose PAD, and transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2) is one of the commonly used noninvasive examinations reflecting local arterial blood flow.7,8) Amann et al. reported that TcPO2 is a useful measurement for evaluating blood flow recovery in patients with CLI who underwent BMCI.9) In a previous investigation, we demonstrated that 99mtechnetium-tetrofosmin (99mTc-TF) perfusion scintigraphy is useful for the assessment of quantitavive blood flow after BMCI.5) However, among these non-invasive examinations of blood flow, predictors of limb salvage in patients with CLI subjected to BMCI have not been established.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of these non-invasive measurements of blood flow as predictors of limb salvage after BMCI in patients with CLI.

Methods

Patient selection

We enrolled 20 consecutive patients who gave their written informed consent and who met the following criteria: a) atherosclerotic PAD or Buerger’s disease with total occlusion or severe stenosis of leg arteries below popliteal artery diagnosed by digital subtraction angiography, b) CLI with Rutherford classification II-4 to IV-6 (Fontaine class 3 or 4) unsuitable for peripheral catheter intervention or bypass surgery, c) continuous ischemic symptoms for more than 6 months despite other conventional treatments, d) no evidence of malignant disorder during the past 5 years and no proliferative diabetic retinopathy, e) male or female aged 20–79 years. Preoperative screening was performed as described previously,5) and the therapeutic decision was made by the advisory committee (consisting of cardiologists, vascular surgeons, plastic surgeons, radiologists and anesthesists).

At 12 weeks of follow up after BMCI, the patients were retrospectively divided into a salvage group (n = 15) and an amputation group (n = 4). Major amputation was defined as amputation above the ankle joint,3) and limb salvage was defined as avoidance of major amputation. We performed partial amputation of the toes for complete necrosis or local osteomyelitis. One patient was excluded from this study because he died of congestive heart failure 60 days after BMCI.

The medical ethics committee of Nippon Medical School reviewed and approved this clinical trial.

Cell preparation and implantation

Bone marrow cell implantation was performed as described previously.5) In brief, approximately 500 ml of bone marrow fluid was aspirated from the bilateral iliac bones of the patient under general anesthesia and collected in a sterile bag containing heparinized (20,000 units) RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). The mononuclear cell fraction was sorted using an AS TEC 204 blood cell separator (Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) and processed to obtain a final volume of about 70 ml. Finally, we injected the mononuclear cell suspension (1 ml/point) intramuscularly into the ischemic regions.

Assessment of limb ischemia

ABI was determined as the ratio of ankle systolic blood pressure to brachial systolic blood pressure, with both measured using an automatic device (PWV / ABI; Colin, Ltd., Komaki, Japan). The device simultaneously measured bilateral brachial and ankle blood pressure by the modified oscillometric pressure sensor method. The higher brachial pressure on either the left or right was used for calculating ABI. It was not possible to assess ABI in one patient in the salvage group because of cuff pain.

TcPO2 was measured by a TCM 400 (RADIOMETER Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The sampling site was carefully selected so as not to overlie a bony prominence, superficial vessel, or pulse site. After wiping the skin with alcohol, we placed a transducer on the dorsum of the ischemic limb and warmed the skin to 43.5≡C to increase the permeability of the skin to oxygen molecules at the measurement site. With the patient resting in the supine position, we acquired baseline TcPO2 at ambient conditions for about 20 min. Then, we repeated the acquisition, this time at 5 L/min pure oxygen inhalation for 5 min, to determine the TcPO2 value in response to an oxygen challenge (maximum TcPO2).

99mTc-TF perfusion scintigraphy was performed as described previously.10) Simply, approximately 10 min after intravenous injection of 99mTc-TF (555–740 MBq), we preformed whole-body scintigraphy of the patient in the prone position, for both anterior and posterior projections, with a dual-head large field-of-view gamma camera (Vertex, ADAC). Each head of the gamma camera was equipped with a high-resolution, low-energy collimator. Scan speed was 12 cm/min. Image acquisition time was approximately 15 min. Data were acquired in a 512 × 1024 matrix and a 2096 window centered on the 140 keV photopeak of 99mTc. Both the anterior and posterior views were used for the quantitative analysis. Regions of interest (ROI) of equal size were drawn around the lower leg (region from knee to ankle) and the foot (region from ankle to toes) in the anterior and posterior projections (muscle uptake; M).10) Additionally, intracranial uptake (brain uptake; B) was obtained and used as background. 99mTc-TF perfusion index was defined as muscle-to-brain (M/B) ratio of averaged counts per pixel.5) Two patients in the salvage group did not undergo 99mTc-TF perfusion scintigraphy.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Intergroup comparisons were made with Student’s t test or chi-squared test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the predictive accuracy of examinations. Areas under the ROC curves and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and compared using a nonparametric test. Then, the best cut-off value for each measurement to predict limb salvage was determined as the one that minimized the distance to the ideal point (sensitivity = specificity = 1) on the ROC curve.11) Time to major limb amputation was compared between the two groups, divided by the cut-off value using Kaplan-Meier analysis with the log-rank test. A value of p <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The overall limb salvage rate in this study was 79%. The reasons for major amputation were uncontrolled infection (n = 3) and acute limb ischemia (n = 1). The clinical characteristics of the limb salvage and amputation groups are summarized in Table 1. The major cause of CLI was atherosclerotic PAD, but five patients with Buerger’s disease were included in the salvage group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in age, sex, Rutherford classification (Fontaine class), prevalence of smoking, hypertension, diabetes and hemodialysis. The use of aspirin, cilostazol, anti-hypertensive drugs, statins and insulin did not significantly differ between the two groups. Laboratory data before BMCI were also comparable between the two groups; however, LDL-cholesterol and estimated GFR were significantly higher in the salvage group than in the amputation group (p <0.05). The number of collected bone marrow mononuclear cells was 6.0 ± 3.5 × 109 in the salvage group and 4.9 ± 1.1 × 109 in the amputation group, with no significant difference between the two groups.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics.

Perfusion parameters prior to BMCI

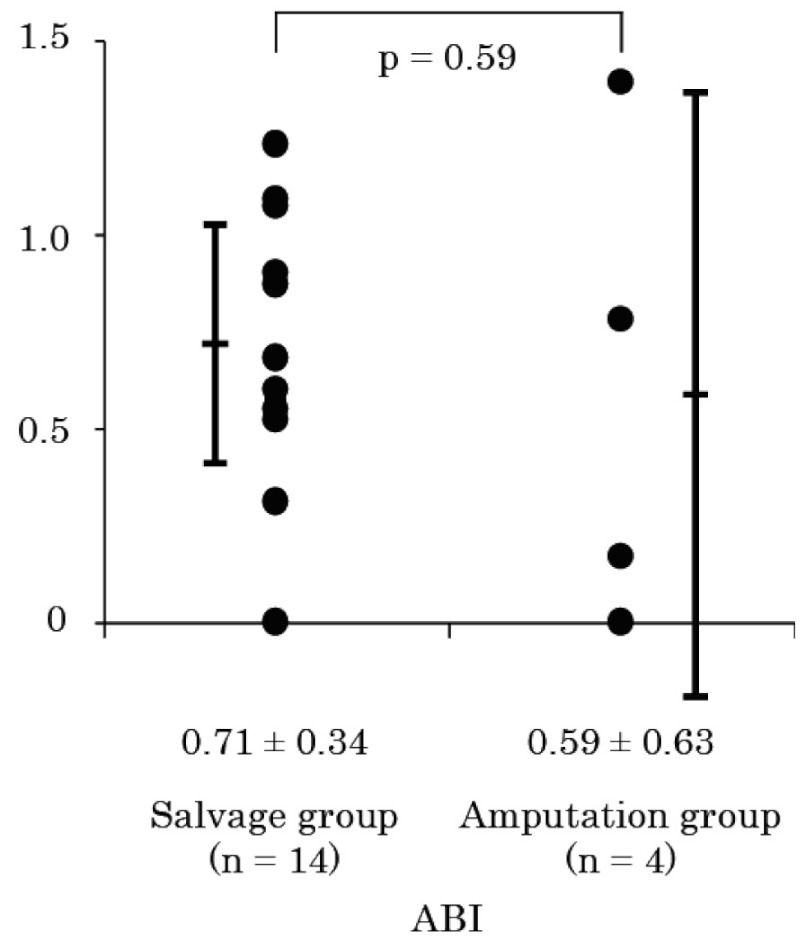

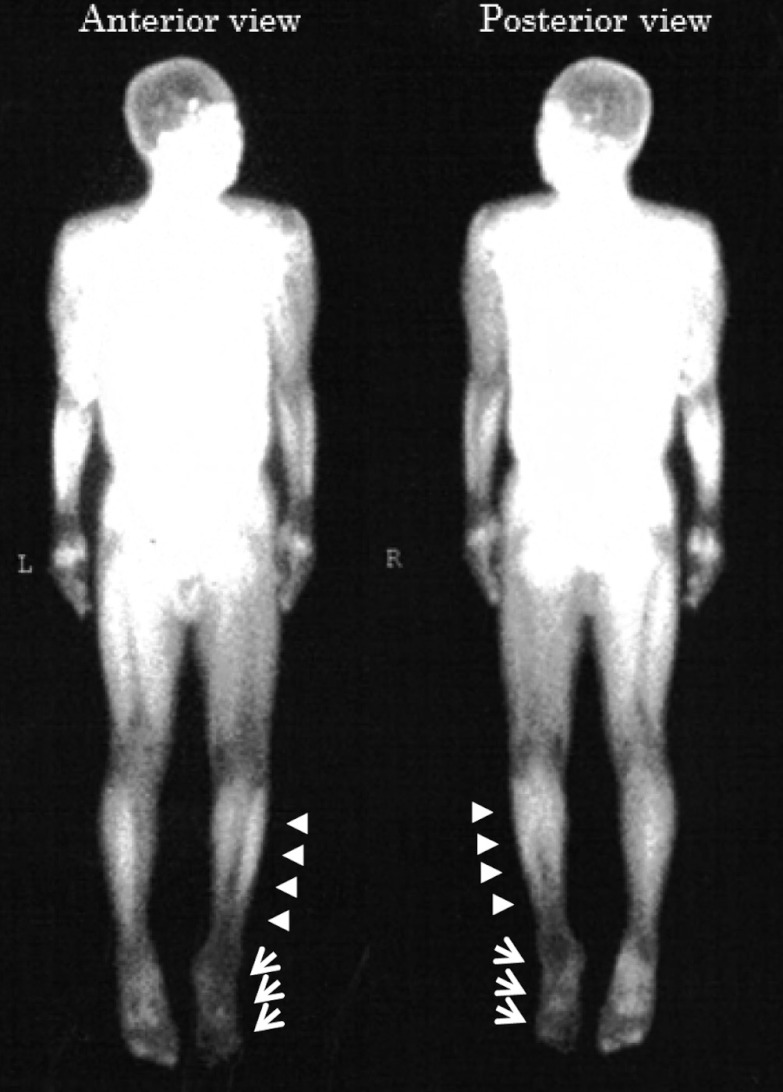

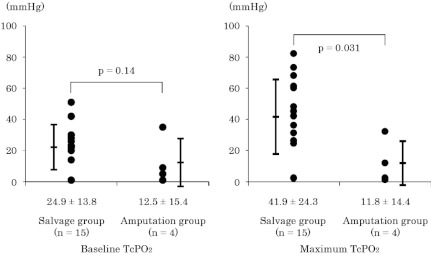

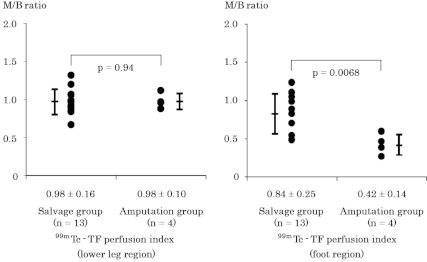

Fig. 1 shows ABI within one week before BMCI. There was no significant difference in ABI between the two groups (0.71 ± 0.34 in salvage group vs. 0.59 ± 0.63 in amputation group, p = 0.59). In Fig. 2, TcPO2 values in the absence (baseline) or presence (maximum) of pure oxygen inhalation were compared. Although the difference in baseline TcPO2 between the two groups was not significant (25 ± 14 vs. 13 ± 15 mmHg, p = 0.14) (Fig. 2A), maximum TcPO2 was significantly higher in the salvage group than in the amputation group (42 ± 24 vs. 12 ± 14 mmHg, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). Fig. 3 shows a representative image of 99mTc-TF perfusion scintigraphy, and perfusion index at the foot (ankle to toes), and lower leg (knee to ankle) regions were calculated. The perfusion index in the lower leg region was comparable between the two groups (0.98 ± 0.16 vs. 0.98 ± 0.10, p = 0.94) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, tissue perfusion of the foot region was estimated to be significantly greater in the salvage group than in the amputation group (0.84 ± 0.25 vs. 0.42 ± 0.14, p = 0.0068) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 1.

Ankle brachial index before bone marrow cell implantation.

Fig. 2.

Transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2) measurements at ambient conditions (A: baseline TcPO2) and during 5 min of pure oxygen inhalation at 5 mL/min (B: maximum TcPO2).

Fig 3.

Representative image of 99mTc-TF perfusion scintigraphy. Arrow-heads indicate lower leg region, and arrows indicate foot region of ischemic leg.

Fig. 4.

Tissue blood flow estimated by 99mTc-TF perfusion scintigraphy (99mTc-TF perfusion index: expressed as muscle to brain [M/B] ratio of mean counts per pixel). Lower leg region (A) and foot region (B).

Cut-off values for limb salvage

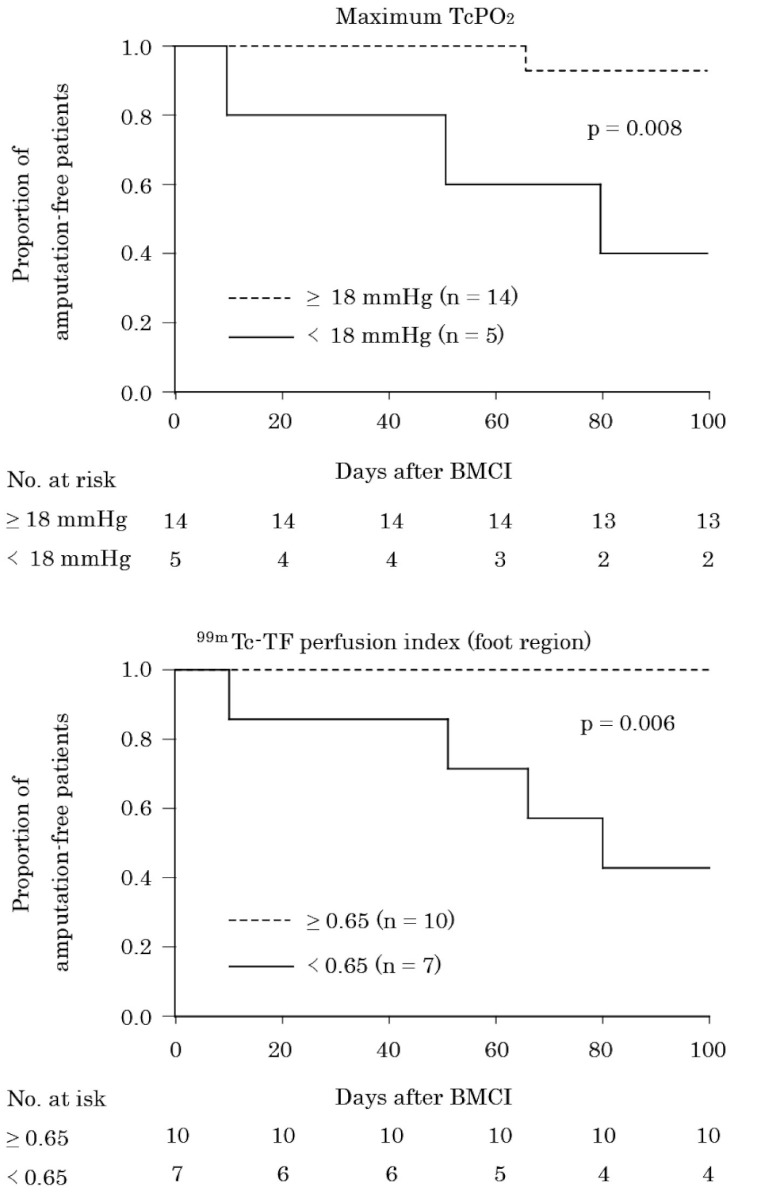

The area under the ROC curve was 0.85 [95% CI 0.66–1.05; p = 0.036] for maximum TcPO2 and 0.94 [95% CI 0.82–1.07; p = 0.009] for 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region, suggesting high predictive accuracy of these parameters for limb salvage. The calculated best cut-off value was 18 mmHg for maximum TcPO2 (sensitivity 0.87, specificity 0.75) and 0.65 for 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region (sensitivity 0.77, specificity 1.0). Fig. 5 illustrates major amputation-free survival when the patients were divided into two groups by these cut-off values. Patients with maximum TcPO2 and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region above the cut-off value had a significantly higher limb salvage rate than those whose measurements were below the cut-off value (log-rank test, p = 0.008, p = 0.006, respectively) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Kaplan-Meier plots of time to major limb amputation dichotomized at the cut-off values of maximum TcPO2 (A) and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region (B).

Discussion

Because the major reason for amputation in CLI is an unhealed ulcer or gangrene, one of the important objectives of therapeutic angiogenesis is wound healing and prevention of ischemic ulcers. Therapeutic angiogenesis by BMCI is thought to improve the microcirculation, playing a crucial role in wound healing.12) The possible mechanism is that bone marrow mononuclear cells consist of a variety of cell populations committed to vascular formation,13) secretion of angiogenic cytokines,14) and stimulation of muscle cells, promoting the secretion of angiogenic factors.15)

In the present study, the mean value of baseline TcPO2 of all patients was 22 ± 15 mmHg, which was almost identical to the cut-off value for limb amputation previously reported.8,12,16) Even for patients in this critical condition, we achieved a 79% limb salvage rate at 12 weeks of follow up after BMCI, indicating that BMCI could be used as a powerful strategy for CLI to salvage limbs from major amputation.

In the present study, the value of TcPO2 was significantly different between the two groups, only when taken during O2 inhalation (maximum TcPO2). Furthermore, the ROC curve analysis showed that maximum TcPO2 is highly accurate in predicting limb salvage. It is reported that maximum TcPO2 is a useful predictor of limb amputation in PAD,17) and our data support this concept as well. The underlying mechanism is that maximum TcPO2 could reveal the remaining potential of flow reserve which is masked under a normoxic condition, by increasing the arterial oxygen content.18) Thus, maximum TcPO2 rather than baseline TcPO2 might represent the severity of ischemia more accurately.

In our previous investigation, the 99mTc-TF perfusion index was shown to be a useful examination to evaluate the increase in blood flow of the microcirculation in response to BMCI.5) The usefulness of 99mTc-TF is supported by the following mechanism: 1) 99mTc emits high energy photons, enhancing image quality, and the shorter half-life allows administration of a higher dosage,19) 2) 99mTc represents both blood flow perfusion and cellular viability, because uptake and retention are dependent on cell membrane integrity and mitochondrial function.19,20)

In the present study, we demonstrated that 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region prior to BMCI was a significant predictor to divide patients into a salvage group and an amputation group. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis indicated 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region to have high predictive accuracy.

We showed the cut-off values of maximum TcPO2 and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region for limb salvage, which was determined by ROC curve analysis, and subsequent Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that these cut off values estimated chronological changes in limb salvage. These findings provide important clinical precognition of responders to BMCI before treatment. Furthermore, to salvage the limbs of patients subjected to BMCI with values below the cut-off values, additional or alternative intervention may be required.

It was important to compare these cut-off values including the patients treated with conventional therapy. However, patients enrolled in this study were already scheduled to have a limb amputation, even before the consultation at our hospital. Thus, we could not randomize the patients to a BMCI treatment group versus a conventional treatment group, for ethical reasons. Even in such “no-option” patients, we encourage to find a possibility of limb salvage. Although clinicians who participate in the care of CLI sometime face an immediate decision of limb amputation, we believe that providing various treatment options for CLI would provide a better prognosis in CLI patients.

In the present study, there was no significant difference in ABI between the two groups. Although ABI is considered to be a useful method in the diagnosis of PAD, it does not represent blood flow of the microcirculation, which is an important factor in wound healing in CLI.12) Besides, severe calcification causes a pseudo-normalized value, which may affect the accuracy of the evaluation of ischemic severity.

In summary, BMCI was performed in 19 CLI patients, and the limb salvage rate was 79%. Maximum TcPO2 and 99mTc-TF perfusion index in the foot region are predictors of limb salvage after BMCI in CLI patients.

Study limitations

There are several limitations of the present study. First, this was a retrospective study with a small number of subjects. Therefore, multivariate analysis was not performed. For ROC curve analysis, the small number of outcomes made the curve rough. In addition, the cut-off values determined by this ROC curve analysis might be inadequate. Second, limb salvage was determined at 12 weeks of follow up after BMCI, which may be too short a follow-up period. Third, blood concentration of LDL-cholesterol and estimated GFR at baseline were significantly higher in the salvage group than in the amputation group, suggesting that patient characteristics might also have influenced the outcome. The results of this study need to be confirmed in a large population.

References

- 1.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL.ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47: 1239–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welten GM, Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Chonchol M, Vidakovic R, van Domburg RT.Long-term prognosis of patients with peripheral arterial disease: a comparison in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1588–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG.Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007; 33(Suppl 1): S1–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertele V, Roncaglioni MC, Pangrazzi J, Terzian E, Tognoni EG. Clinical outcome and its predictors in 1560 patients with critical leg ischaemia. Chronic Critical Leg Ischaemia Group. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1999; 18: 401–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto M, Yasutake M, Takano H, Takagi H, Takagi G, Mizuno H.Therapeutic angiogenesis by autologous bone marrow cell implantation for refractory chronic peripheral arterial disease using assessment of neovascularization by 99mTc-tetrofosmin (TF) perfusion scintigraphy. Cell Transplant 2004; 13: 429–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tateishi-Yuyama E, Matsubara H, Murohara T, Ikeda U, Shintani S, Masaki H.Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischaemia by autologous transplantation of bone-marrow cells: a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 427–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White RA, Nolan L, Harley D, Long J, Klein S, Tremper K.Noninvasive evaluation of peripheral vascular disease using transcutaneous oxygen tension. Am J Surg 1982; 144: 68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyss CR, Matsen FA, 3rd, Simmons CW, Burgess EM. Transcutaneous oxygen tension measurements on limbs of diabetic and nondiabetic patients with peripheral vascular disease. Surgery 1984; 95: 339–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amann B, Luedemann C, Ratei R, Schmidt-Lucke JA. Autologous bone marrow cell transplantation increases leg perfusion and reduces amputations in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia due to peripheral artery disease. Cell Transplant 2009; 18: 371–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kijima T, Kumita S, Cho K, Kumazaki T. 99mTc-tetrofosmin exercise leg perfusion scintigraphy in arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO)—assessment of leg ischemia using two phase data acquisition. Kaku Igaku 1998; 35: 305–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983; 148: 839–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalani M, Brismar K, Fagrell B, Ostergren J, Jorneskog G. Transcutaneous oxygen tension and toe blood pressure as predictors for outcome of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 147–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M.Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res 1999; 85: 221–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamihata H, Matsubara H, Nishiue T, Fujiyama S, Tsutsumi Y, Ozono R.Implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells into ischemic myocardium enhances collateral perfusion and regional function via side supply of angioblasts, angiogenic ligands, and cytokines. Circulation 2001; 104: 1046–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tateno K, Minamino T, Toko H, Akazawa H, Shimizu N, Takeda S.Critical roles of muscle-secreted angiogenic factors in therapeutic neovascularization. Circ Res 2006; 98: 1194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takolander R, Rauwerda JA. The use of non-invasive vascular assessment in diabetic patients with foot lesions. Diabet Med 1996; 13(Suppl 1): S39–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harward TR, Volny J, Golbranson F, Bernstein EF, Fronek A. Oxygen inhalation—induced transcutaneous PO2 changes as a predictor of amputation level. J Vasc Surg 1985; 2: 220–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheffler A, Rieger H. Clinical information content of transcutaneous oxymetry (tcpO2) in peripheral arterial occlusive disease (a review of the methodological and clinical literature with a special reference to critical limb ischaemia). Vasa 1992; 21: 111–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slart RH, Bax JJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Wall EE, Dierckx RA, Jager PL. Imaging techniques in nuclear cardiology for the assessment of myocardial viability. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2006; 22: 63–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Travin MI, Bergmann SR. Assessment of myocardial viability. Semin Nucl Med 2005; 35: 2–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]