Abstract

Objective: In patients with isolated soleal vein thrombosis (SVT), the relation between acute thrombi and positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was investigated.

Subjects and Methods: The subjects were 116 lower extremities in 86 patients with SVT. They were diagnosed and examined by ultrasonography and blood serum analysis (D-dimer, ANA), and had been followed up every three months.

Results: They had acute SVT in 35 limbs (30%) and chronic SVT in 86 limbs (70%), and they had positive ANA in 63%. They had recurrent SVT in 26%, and all were positive for ANA.

Conclusion: ANA-positivity might be a risk factor for acute thrombi in patients with SVT. (*English Translation of J Jpn Coll Angiol 2010; 50: 417-422.)

Keywords: isolated soleal vein thrombosis, recurrent deep vein thrombosis, risk factor, antinuclear antibody

Introduction

In an acute period of deep vein thrombosis, early diagnosis and treatment are important for the prevention of acute pulmonary artery thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism). In the remote period, also, continuous management is necessary to avoid recurrent pulmonary embolism due to the recurrence of thrombosis. However, the pathogenesis of recurrence still remains unclear in many respects. Various risk factors of deep vein thrombosis have been reported, and sustained risk factors such as a thrombotic predisposition are involved in the recurrence.1) Lupus anticoagulant or anti-cardiolipin antibody, which is an autoantibody in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, has been shown to be risk factors of deep vein thrombosis.2) Antinuclear antibody, which is an autoantibody, is positive in a high percentage of patients with collagen disease and is involved in vascular disorders such as Raynaud's phenomenon3) and may, therefore, be a risk factor of deep vein thrombosis.

In this study, we aimed to clarify the relationship between isolated venous thrombi in soleal muscle and antinuclear antibody.

Subjects and Methods

The subjects were 89 patients with 116 limbs with isolated soleal vein thrombosis (SVT) among the 124 patients with 170 limbs with deep vein thrombosis of the pelvis and lower limbs diagnosed and treated between April 2006 and May 2009. Their mean age was 70 ± 14 years. SVT was observed slightly more frequently in females than in males, with a male/female ratio of 1:1.4, and more frequently unilaterally than bilaterally at a ratio of 1:0.4. However, it showed no laterality, affecting the left and right at a ratio of 1:1.1. The primary reason for the consultation was to search for deep vein thrombosis in 41 limbs, or to investigate lower leg pain in 29, leg edema in 24, and leg varices in 22. Collagen or autoimmune disease was observed in 3 patients (scleroderma, primary biliary cirrhosis, and chronic thyroiditis). Of the risk factors of deep vein thrombosis, primary varicose vein (saphenous type) was observed in 35%, chronic heart failure in 30%, prolonged bed rest in 12%, surgery of a lower limb in 11%, abdominal surgery in 10%, Buerger's disease in 10%, fracture of a lower limb in 7%, pregnancy in 2%, and oral steroid use in 2%.

As for examinations, ultrasonography and blood tests were performed for the diagnosis and follow-up thereafter. Ultrasonography of the pelvic and lower limb veins was performed a total of 592 times, all by the same physician. By ultrasonography, deep vein thrombosis was diagnosed by compression with the probe in the 2D and color Doppler modes. The body position during ultrasonography was seated or supine with the legs hanging. Thrombi were classified into early and late ones.4,5) The degree of retraction of thrombi was evaluated semi-quantitatively according to a 4-grade scale: Early-stage thrombi with no retraction, early-stage thrombi with slight retraction (half the diameter of the vein or larger), late-stage thrombi showing moderate retraction (less than half the diameter of the vein but larger than 2 mm), and late-stage thrombi showing marked retraction (2 mm or smaller). After the diagnosis, changes in the degree of retraction of the thrombi were evaluated semi-quantitatively using a 3-grade scale: Non-retracted or slightly-retracted thrombi that increased in size (increase), moderately-retracted thrombi that showed no change in size (same), and highly-retracted thrombi that showed a decrease in size (decrease). The proximal end of the thrombus was examined for proximal progression. Concerning arterial disorders, the state of blood flow was evaluated according to the Doppler blood flow sounds (phase 3, phase 2, phase 1, no blood flow). Phases 3 and 2 were regarded as normal, and phase 1 and no blood flow as reduced. On blood tests, D-dimer (latex immunoturbidimetry) and antinuclear antibody (fluorescent antibody method) levels were determined. In patients showing multiple thrombi or recurrence, lupus anticoagulants and coagulation inhibitors (antithrombin, protein S, and protein C) were also examined. A D-dimer level of 1.0 µg/ml or higher, an antinuclear antibody level of × 40 or higher, a lupus anticoagulant level of 1.3 or lower, an antithrombin activity of 79% or lower, a protein S total antigen level of 65% or lower, and a protein C antigen level of 70% or lower were regarded as abnormal.

The diagnosis was acute SVT when lower leg pain was noted in the medical interview or tenderness was noted in the soleal muscle by examination and/or when the thrombus was judged to be early-stage or late-stage accompanied by an abnormal D-dimer level.6) SVT was judged to be chronic when the thrombus was late-stage. The patients were followed up by an interview and examinations within 1 month, after 3 months, and every 3 months thereafter, and ultrasonography and the measurement of the D-dimer and antinuclear antibody levels were also performed when necessary. On follow-up examinations, thrombosis was considered to have recurred both when there was lower leg pain or tenderness of the soleal muscle and/or when an early-stage thrombus or a late-stage thrombus accompanied by an abnormal D-dimer level was noted.6)

Acute SVT was treated by a combination of anticoagulant and compression therapy. Chronic SVT and acute SVT with no indication of anticoagulant therapy were treated by a combination of compression and exercise therapy. Patients with chronic thrombosis not wishing for compression therapy were treated by exercise therapy alone. Anticoagulant therapy was performed by administering heparin at 3000 U subcutaneously 2 times/day over 5 days and a low dose (2 mg/day) of warfarin over 3 months. Compression therapy was performed by having the patients wear elastic stockings (knee-high socks) or an elastic bandage (lower leg) during the daytime. Exercise therapy consisted of guidance in walking (for 30 minutes or longer in the morning and evening) for those who could walk, ankle flexion and extension (for 10 minutes or longer in the morning and evening) for those with difficulty in walking, and massage of the lower legs (for 10 minutes or longer in the morning, around noon, and in the evening) for those who could not walk.

The mean values are presented with 1 standard deviation. The t-test was performed for comparisons of homoscedastic data between 2 groups, and the Cochran-Cox test was performed for comparisons of non-homoscedastic data between 2 groups. The chi-square test was performed for comparisons of ratios between 2 groups. The level of significance was P <0.05 in all tests.

Results

1. Findings at the diagnosis

1) Symptoms and physical findings

SVT was acute in 35 limbs (30%) and chronic in 81 (70%). As for symptoms, lower leg pain was noted in 12%, and leg heaviness was noted in 17%. Physical findings were edema in 41% and tenderness of the soleal muscle in 21%. As complications, 3 patients had symptomatic pulmonary embolism, and 1 with atrial septal defect developed cerebral infarction due to paradoxical embolism.

2) Evaluation of thrombi

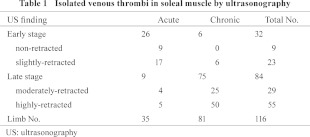

On the evaluation of thrombi by ultrasonography at the diagnosis, the thrombi were judged to be in the early stage in 32 limbs (28%) and in the chronic stage in 84 limbs (Table 1). In the 35 limbs with acute thrombosis, no retraction and slight retraction were observed in 26% and 49%, respectively, with early-stage thrombi accounting for 75%. In the 81 limbs with chronic thrombosis, 31% showed moderate retraction, and 62% showed marked retraction, with late-stage thrombi accounting for 93%.

3) Blood test results

The blood tests at the diagnosis showed an increase in the D-dimer level to 1.4 ± 1.4 µg/ml in those with acute thrombosis but a normal D-dimer level of 0.8 ± 1.1 µg/ml in those with chronic thrombosis, with no significant difference. The percentage of patients with an abnormal D-dimer level was 47% (9/19) in those with acute thrombosis and was significantly higher than 8% (3/37) in those with chronic thrombosis (P <0.01).

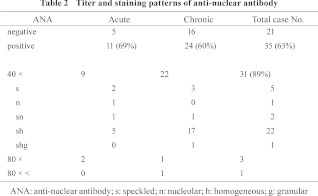

Concerning autoantibodies, lupus anticoagulant was positive in 0% (0/5). Antinuclear antibody was positive in 63% (35/56), but no significant difference was noted between the acute and chronic groups (Table 2). The antibody titer was 1:40 in 89%. The staining pattern was speckled and homogeneous in 66%, and the speckled pattern was observed in 94% of all patients. The antibody titer and staining pattern were 1:160 and speckled in the patient with scleroderma, 1:40 and speckled/homogeneous in the patient with chronic thyroiditis, and 1:40 and speckled, 1:80 and cytoplasmic, and 1:80 and granular in the patient with primary biliary cirrhosis.

Concerning coagulation inhibitors, proteins S and C decreased in 0% (0/5), but a slight decrease (70%) in the antithrombin activity was noted in 1 patient.

4) Cryesthesia

Symptoms of cryesthesia including Raynaud's phenomenon were noted in 45% (17/38) of the patients positive, and 39% (7/18) of those negative, for antinuclear antibody. A decrease in the blood flow of the dorsalis pedis artery was observed in 32% (12/38) of the antinuclear antibody-positive patients and 15% (2/13) of the negative patients, but this difference was not significant.

2. Therapeutic results

As early treatments within 3 months, anticoagulant therapy was performed in 6, compression therapy in 26, and exercise therapy in 3 of the limbs with acute thrombosis. Recurrence was observed in 6%, i.e., 1 limb treated by anticoagulant therapy and 1 limb treated by compression therapy. In the limbs with chronic thrombosis, anticoagulant therapy was performed in 2, compression therapy in 37, and exercise therapy in 42, with no recurrence.

As sustained treatments after more than 3 months, anticoagulant therapy was performed in 2, compression therapy in 9, and exercise therapy alone in 24 of the limbs with acute thrombosis. Recurrence was observed in 11%, i.e., 3 limbs treated by exercise therapy alone and 1 limb treated by compression therapy. Anticoagulant therapy, compression therapy, and exercise therapy alone were performed in 1, 28, and 52, respectively, of the limbs with chronic thrombosis, and recurrence was noted in 10%, i.e., 3 limbs treated with compression therapy and 5 limbs treated with exercise therapy alone.

3. Recurrence after the diagnosis

1) Re-evaluation of thrombi

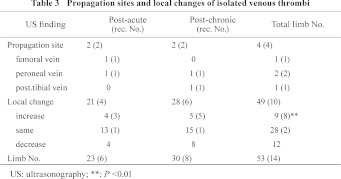

Thrombi were re-evaluated after the diagnosis in 53 limbs (46%). Recurrence was observed in 14 limbs (26%), with propagation and local recurrence accounting for 4 (8%) and 10 (19%) limbs, respectively (Table 3). Local recurrence was observed in 89% (8/9) of the thrombi that increased in size compared with 7% (2/28) of the thrombi that showed no change (P <0.01). In the limbs with acute thrombosis, recurrence was observed in 26%, i.e., propagation in 2 limbs and local recurrence in 4 limbs. In the limbs with chronic thrombosis, recurrence was observed in 27% as propagation in 2 and local recurrence in 6. The frequency of recurrence did not differ significantly between the acute and chronic groups.

2) Recurrence and antinuclear antibody

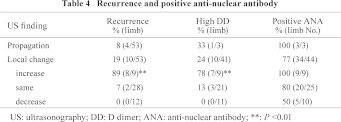

Of the 14 limbs with recurrence, the antinuclear antibody was positive in all (13/13) but 1 limb in which it was not measured. As for change in the degree of retraction after local recurrence, the D-dimer level was high in 78% of the limbs that increased in size and in 13% of those that showed no change (P <0.01) and was normal in all limbs that decreased in size (Table 4). However, antinuclear antibody was positive in 100% of those that showed an increase, 80% in those that showed no change, and 50% in those that showed a decrease.

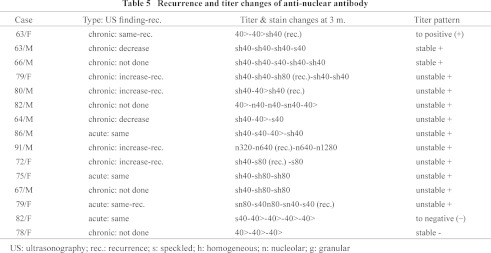

The relationship between recurrence and changes in the antibody level was evaluated in the 15 limbs in which antinuclear antibody was measured 3 or more times during the course (Table 5). The antibody remained or became positive in 13 and remained or became negative in 2. Antinuclear antibody was positive in the 6 limbs that showed recurrence, and recurrence was observed in 5 of them during the period showing increases in the antibody level.

Discussion

The accuracy of the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis by ultrasonography varies with the site. In pelvic or lower limb deep vein thrombosis, the accuracy of the diagnosis is satisfactory in the femoral region1,5) but insufficient in the iliac and crural regions.6,7) However, compared with the iliac region, reasonable diagnostic accuracy is expected with experience in the crural region.8,9) A characteristic of ultrasonography is that early- and late-stage thrombi can be distinguished based on the brightness of the image and compressibility of the vein.1,4,5) While fresh thrombi can be evaluated readily, the evaluation becomes more difficult as retraction progresses, but the diagnostic limitation has not been determined.1,5,10) In this study, retraction of venous thrombi was evaluated semi-quantitatively by applying a 4-grade scale to the degree of retraction and a 3-grade scale to its changes. By the compression method, the venous compressibility is judged to be normal when the vein disappears on compression with the probe but to be abnormal when it does not.1) Here, marked retraction to less than 2 mm in diameter was regarded as the diagnostic limit.

The distal type of deep vein thrombosis with no marked venous return disturbance is difficult to diagnose compared with the proximal type. Particularly, isolated SVT shows few signs or symptoms, and the distinction between acute and chronic thrombosis is not easy.9,11) In acute thrombosis, it is practical to make a tentative diagnosis on the basis of interviews and examinations and a definitive diagnosis on the basis of objective examinations.7,10) In this study, ultrasonography and D-dimer measurement were indicated in patients with pain or tenderness of the lower leg, and diagnoses of acute thrombosis and recurrence after the diagnosis were made on the basis of the detection of early-stage thrombi or late-stage thrombi accompanied by a high D-dimer level. Chronic thrombosis was diagnosed on the basis of the detection of late-stage thrombi.

SVT was acute in 30% of the patients. Chronic SVT was more prevalent, because examinations were performed more frequently for edema or varices of the lower limbs. As for risk factors, prolonged bed rest and lower limb fracture were observed frequently in patients with acute SVT, and lower limb varices and chronic heart failure were observed frequently in patients with chronic SVT. In the recurrence observed during the course, an involvement of existing risk factors cannot be excluded, but other sustained factors are considered to have contributed to repeated recurrence.1,5)

In this study, coagulation inhibitors and autoantibodies were evaluated regarding the thrombotic tendency by assuming that antinuclear antibody is a risk factor of deep vein thrombosis. Among autoantibodies, as anti-DNA antibody and rheumatoid factor were infrequently positive in a preliminary study, antinuclear antibody and lupus anticoagulant were measured. Antinuclear antibody was positive in 63% of the patients with SVT, and an antibody titer of 1:40 with a speckled and homogeneous stain pattern (66%) was observed most frequently, accounting for 89%. Antinuclear antibody showed similar characteristics in proximal deep vein thrombosis, and an antibody titer of 1:40 with a speckled and homogeneous pattern is considered to be a common feature of deep vein thrombosis in non-collagen diseases. Since the frequency of positivity of antinuclear antibody was high and equal in both acute and chronic thrombosis, it may be a risk factor related to a thrombotic tendency. However, there has been no report that antinuclear antibody is involved in a thrombotic tendency. In collagen diseases such as scleroderma and SLE, antinuclear antibody is suspected to be related to vascular disorders such as Raynaud's phenomenon and thrombophlebitis.3,12) In our patient, scleroderma was complicated by SVT and peroneal vein thrombosis, and antinuclear antibody was positive at 1:160 with a speckled stain pattern or 1:1,280 or higher with a centromere pattern. Characteristics different from those of non-collagen disease deep vein thrombosis are suggested. On the other hand, Raynaud's phenomenon and thrombophlebitis also appear in Buerger's disease,3,13) which is antinuclear antibody-negative angiitis. In our study, also, Buerger's disease was complicated by SVT in 8 limbs, so angiitis may be a risk factor of deep vein thrombosis.

Antinuclear antibody is considered to promote the thrombotic tendency directly by causing intimal damage due to its binding to the intimal cell wall and indirectly by causing disorder of the intimal function due to its binding to intracellular structures of intimal cells such as the nucleus and cytoplasm.2,3) Unlike antiphospholipid antibody, which binds to the cell wall in a restricted manner, antinuclear antibody binds to various structures of the cell and is considered to more frequently contribute to the thrombotic tendency by diverse mechanisms. On the other hand, in consideration of the pumping function of the soleal muscle as a site-specific factor, vascular disorders may be caused in the artery of the soleal muscle by muscle compression and extend to the accompanying vein.

Recurrence was observed during the course after the diagnosis in 26% of the limbs, close to 30% of the limbs with acute thrombosis. It occurred in 26% of the limbs after acute thrombosis and in 27% of the limbs after chronic thrombosis. Of the 14 limbs that showed recurrence, antinuclear antibody was positive in 13 limbs, excluding the 1 in which antinuclear antibody was not measured. Therefore, being positive for antinuclear antibody may be a sustained risk factor of recurrence. However, on the re-evaluation of thrombi, recurrence was observed more frequently in limbs that showed an increase in the size of thrombi than in those that showed no change or a decrease when there was no significant difference in the positivity rate of antinuclear antibody. Therefore, being positive for antinuclear antibody is judged to be a necessary, but not a sufficient condition of recurrence. Analysis of changes in the antibody level with time showed that thrombosis tended to recur during periods with increases in the antibody level. Changes in the antibody level are classified into sustained negativity, positive conversion, sustained positivity, and negative conversion, and sustained positivity could be divided into stable and unstable types. It is necessary to measure the antibody level at least 3 times to detect a period of increase in the antibody level. More detailed follow-up is necessary to clarify the relationship between antinuclear antibody and recurrence.

Conclusions

We got the following two conclusions; First, in isolated soleal vein thrombosis, positivity for antinuclear antibody may be a risk factor of venous thrombi. Secondly, positivity for antinuclear antibody may contribute to the recurrence of venous thrombi.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no potential conflict of interest to be disclosed.

Footnotes

This article is English Translation of J Jpn Coll Angiol 2010; 50: 417-422.

References

- Ando M, Ohgi S, Ogawa S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of pulmonary thromboembolism and deep vein thrombosis. Circulation J 2004; 68(Suppl. VI): 1079-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki M. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. In: Ichinose A. eds. Sciences of Thrombi, Hemostasis, and Angiology. Tokyo: Chugai-Igakusha, 2005: 410-21 [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Numano F. Angiitis. In: Morishita R, et al. eds. Vascular Medicine. Tokyo: Medical Review, 2001: 565-76 [Google Scholar]

- Ohgi S, Ito K, Tanaka K, et al. Echogenic types of venous thrombi in the common femoral vein by ultrasonic B-mode imaging. Vasc Surg 1991; 25: 253-8 [Google Scholar]

- Meissner MH, Moneta G, Burnand K, et al. The hemodynamics and diagnosis of venous disease. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46(Supple. S): S4-S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins DL, Semrow CM, Friedell ML, et al. Progress in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis: the efficacy of real-time B-mode ultrasonic imaging. J Vasc Surg 1988; 7: 638-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis MM, Ranval TJ, Nix ML, et al. Is anticoagulation indicated for asymptomatic postoperative calf vein thrombosis? J Vasc Surg 1992; 16: 414-8, discussion 418-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JM, James KV, Deshmukh RM, et al. Allastair B. Karmody Award Calf vein thrombi are not a benign finding. Am J Surg 1995; 170: 86-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgi S, Tachibana M, Ikebuchi M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with isolated soleal vein thrombosis. Angiology 1998; 49: 759-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgi S, Kanaoka Y. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. J Med Ultrasonics 2004; 31: J337-46 [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JM, Kerr TM, Lutter KS, et al. Lower extremity calf thrombosis: to treat or not to treat? J Vasc Surg 1991; 14: 618-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenberg CG, Wouda AA, The TH. Systemic involvement and immunologic findings in patients presenting with Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1980; 69: 675-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S, Ando F, Izuishi K, et al. Guidelines for Management of Vasculitis Syndrome. Circulation J 2008; 72(Suppl. IV): 1253-318 [Google Scholar]