Abstract

Depression is highly prevalent among HIV-infected patients, yet little is known about the quality of HIV providers' depression treatment practices. We assessed depression treatment practices of 72 HIV providers at three academic medical centers in 2010–2011 with semi-structured interviews. Responses were compared to national depression treatment guidelines. Most providers were confident that their role included treating depression. Providers were more confident prescribing a first antidepressant than switching treatments. Only 31% reported routinely assessing all patients for depression, 13% reported following up with patients within 2 weeks of starting an antidepressant, and 36% reported systematically assessing treatment response and tolerability in adjusting treatment. Over half of providers reported not being comfortable using the full FDA-approved dosing range for antidepressants. Systematic screening for depression and best-practices depression management were uncommon. Opportunities to increase HIV clinicians' comfort and confidence in treating depression, including receiving treatment support from clinic staff, are discussed.

Introduction

Depression is a common condition in people living with HIV/AIDS, with prevalence ranging from 20% to 30%.1,2 Despite its high prevalence, depression is commonly underdiagnosed and undertreated in this population.3 The under-recognition of depression among people living with HIV/AIDS not only leads to ongoing psychiatric morbidity, but can also contribute to higher sexual and injection drug use risk behaviors, poor antiretroviral (ARV) adherence, and worse clinical outcomes.4,5 Although the burden of depression is high, access to specialty mental health care for this largely disenfranchised and uninsured population may be limited. HIV providers, who often serve as primary care providers to their patients, frequently play an important role in identification and management of depression, especially given increasing emphasis on “medical home” models for HIV care.6

Although the importance of depression and depression management for HIV clinical care has been long recognized, little is known about the quality or the extent of depression care that is provided by HIV clinicians. Two decades of research and policy initiatives have focused on integrating depression management into primary care practice, and convincing evidence has demonstrated the capacity of nonpsychiatric providers to deliver quality depression care, especially through use of decision support and collaborative care models.7,8 Such models generally deploy nonprescribing “care managers” with expertise in depression management who follow evidence-based guidelines to advise nonpsychiatric providers in identifying depression and managing treatment.9 Similar efforts in medical settings for chronically ill patient populations (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular, or HIV patients) are at an earlier stage of development. In order to assess the potential of such models to improve the capacity for and quality of depression care within HIV clinical settings, an evaluation is warranted of the current status of depression care including HIV providers' attitudes toward providing depression care and current practices relating to identifying and treating depression.

This article aims to describe HIV medical providers' attitudes and practices toward diagnosing, treating, and managing depression in HIV clinical settings and to compare current practices to national evidence-based depression treatment guidelines.

Methods

Participating sites were outpatient Infectious Diseases clinics at three academic medical centers, each of which serves >1500 HIV-infected patients, during preparation for a multisite randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment intervention (SLAM DUNC Study, R01MH086362). The three sites have similar patient populations whose characteristics (approximately two-thirds African American, with the remainder primarily non-Hispanic White; approximately two-thirds male; patients primarily in their 30s and 40s, and primarily infected through male-to-male or heterosexual sexual contact) are reflective of the HIV epidemic in the US South. All providers of direct HIV medical care at the three sites were eligible for participation. In-person, semi-structured interviews were conducted by trained staff at each site. The data presented in this article were collected prior to the launch of randomized controlled trial activities at each site (2010 for sites 1 and 2; 2011 for site 3). All study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the respective sites. All participating providers gave written informed consent. Each interview was either audio-recorded and transcribed, or summarized by research personnel during the interview.

Descriptive information about each provider (race, gender, years of clinical experience, and caseload) was collected. Providers were asked to estimate the proportion of their HIV patient caseload that was depressed and the proportion that was receiving treatment for depression. A series of questions assessed providers' comfort with and attitudes toward treating depression in their HIV patients, with responses measured on Likert scales. Finally, open-ended questions asked about providers' current depression treatment practices: how they identify depression, make decisions around treatment initiation, adjust antidepressant treatment to account for interactions with ARV and other medications, assess response to treatment, make decisions around treatment adjustment, and maintain treatment. Interviews were conducted by an interviewer with a graduate-level education.

Definition of best-practices standards

In order to define best practices for depression treatment, two psychiatrists with expertise in evidence-based management of depression (JA, BNG) reviewed general depression treatment guidelines published by the American Psychiatric Association and HIV-specific guidelines published by the New York State Department of Health.10,11 This review yielded nine core principles of best-practices pharmacological treatment of depression: eight principles applicable to all populations and one principle specific to HIV-infected patients taking ARV therapy. These principles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Best Practices Framework: Adapted from the American Psychiatric Association Guidelines, 2010

| Domain | Indicator | Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Identifying depression | Assessment of depression | Routinely assess all patients for depression using standardized measure |

| Initiating antidepressant treatment | Assessment of need for treatment | Assess need for treatment based on symptom-based threshold (i.e., standard cut-off score on standardized measure or clinical judgment of severity), not based on patient request |

| Choice of treatment | Base treatment choice on depression history (e.g., prior treatments) and severity | |

| Adjustment of starting dose for interaction with ARVs | Adjust antidepressant starting dose to account for interaction with antiretrovirals | |

| Managing treatment | First clinical follow-up after treatment initiation | Within 2 weeks to assess tolerability, within 4 weeks to assess efficacy |

| How effectiveness is assessed | Systematic measure of symptoms | |

| When to increase dose | Increase dose based on formal assessment of tolerability or efficacy | |

| How high to increase dose | Titrate up to full FDA-approved range until effect is achieved | |

| When medication is changed | Change medication based on formal assessment of tolerability or efficacy, and only after adequate trial |

Analysis

We described provider and caseload characteristics and providers' confidence in treating depression using medians and interquartile ranges (due to skewed distributions of some continuous variables) or proportions. We used quantitative and qualitative methods to describe the degree of conformity of providers' self-reported depression treatment practices with evidence-based guidelines. A psychiatrist (JA) assigned providers a score for each of the nine best-practices principles based on providers' responses to the open-ended questions about their current practices, with a higher score indicating closer concordance with evidence-based practice (Table 2). To analyze the qualitative data, we utilized content analysis12 to identify themes related to each of the nine indicators of depression treatment practice (Table 1). Two co-authors (KB, MW) reviewed the transcripts and selected representative quotes to summarize the manifest content themes for each indicator. Discrepancies in themes identified or quotes selected were discussed by both raters until consensus was reached. Finally, we used exploratory principal factor analysis13 to assess whether the assigned scores for the nine best-practices indicators could be combined into a single summary best-practices score. We replaced the small number of missing values (0.9%–5 providers were each missing one of nine items) with that participant's mean score on the nonmissing items before calculating the summary (weighted factor) score. An alternative approach of calculating a summary score only from nonmissing items, with all nonmissing items weighted equally, yielded comparable results. After confirming the appropriateness of creating the summary best-practices score and the approximately normal distribution of the resulting scale, we used linear regression models (with robust standard errors to account for clustering by site) to compare summary scores between sub-groups of providers.

Table 2.

Reported Provider Depression Treatment Practices

| Indicator | Response | Assigned scorea | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of depression | ■ Uses standardized depression measure with all patients | 5 | 10 (14%) |

| ■ Routinely asks all patients some screening question(s) | 4 | 13 (18%) | |

| ■ Asks only patients who exhibit signs of depression | 3 | 37 (51%) | |

| ■ Asks only when patients report depression or ask for treatment | 2 | 7 (10%) | |

| ■ No method identified | 1 | 5 (7%) | |

| Assessment of need for treatment | ■ Based on symptom-based threshold (i.e., standard cut-off score on standardized measure or clinical judgment of severity) | 3 | 48 (67%) |

| ■ Treats only when patient asks | 2 | 6 (8%) | |

| ■ No method identified | 1 | 18 (25%) | |

| Choice of treatment | ■ Clinical judgment based on depression history (e.g., prior treatments) and severity | 3 | 39 (54%) |

| ■ Patient asks for a specific treatment | 2 | 0 (0%) | |

| ■ No method identified | 1 | 33 (46%) | |

| Adjustment of starting dose for interaction with ARVs | ■ Yes (adjusts starting dose based on ARV regimen) | 2 | 26 (36%) |

| ■ No (does not adjust starting dose) | 1 | 46 (64%) | |

| First clinical follow-up after treatment initiation | ■ Within 2 weeks | 5 | 9 (13%) |

| ■ 2–4 weeks | 4 | 17 (24%) | |

| ■ 4–6 weeks | 3 | 19 (27%) | |

| ■ >6 weeks | 2 | 12 (17%) | |

| ■ At next clinic visit (∼3 months) | 1 | 13 (19%) | |

| How effectiveness is assessed | ■ Measures symptoms systematically | 4 | 6 (8%) |

| ■ Asks about symptoms | 3 | 40 (56%) | |

| ■ Patient reports symptoms | 2 | 19 (26%) | |

| ■ No method | 1 | 7 (10%) | |

| When medication is titrated | ■ Increases dose based on formal assessment of tolerability or efficacy | 4 | 26 (36%) |

| ■ Increases dose based on informal assessment of depressive signs and symptoms | 3 | 18 (25%) | |

| ■ Increases dose when patient asks | 2 | 15 (21%) | |

| ■ No method identified | 1 | 13 (18%) | |

| How high medication is titrated | ■ Full titration (will use full FDA-approved range) | 3 | 32 (45%) |

| ■ Some titration (will increase dose some but not use full range) | 2 | 34 (48%) | |

| ■ No titration (will not increase dose) | 1 | 5 (7%) | |

| When medication is changed | ■ Decision to change medication based on formal assessment of tolerability or efficacy; changes only after adequate trial | 3 | 12 (17%) |

| ■ Decision to change based on tolerability or efficacy, but not necessarily after an adequate trial | 2 | 45 (64%) | |

| ■ Never changes from initial medication | 1 | 13 (19%) |

Scores from highest (responses closest to best practices) to lowest (responses furthest from best practice).

Results

Description of sample

All eligible providers at the three sites (n=72) were approached and consented to participate in the study (Table 3). About half of the providers (n=38) were attending-level medical doctors (MD), 24 were MD-fellows, 6 were nurse practitioners, and 4 were physician assistants. The sample was fairly evenly split between male and female providers, and the majority of participants were Caucasian (78%). Providers had a median of 8 years of experience treating HIV patients, and 35% had been treating HIV patients for less than 5 years. On average, providers reported that they devote approximately one-third of their total professional effort to clinical work, with three-quarters of their clinical effort dedicated to HIV treatment.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Sample (n=72)

| Characteristic | n (%) | Median (IQR) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | |||

| Duke | 23 (31.9) | ||

| UAB | 24 (33.3) | ||

| UNC | 25 (34.7) | ||

| Clinical role | |||

| MD attending | 38 (52.7) | ||

| MD fellow | 24 (33.3) | ||

| Nurse practitioner | 6 (8.3) | ||

| Physician assistant | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 38 (52.8) | ||

| Female | 34 (47.2) | ||

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 56 (78.9) | ||

| Asian | 5 (7.0) | ||

| African American | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Hispanic | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Indian | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Multiple | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Years treating HIV | 8 (3–16) | 0–30 | |

| 0–4 | 25 (34.7) | ||

| 5+ | 47 (65.3) | ||

| Clinical effort as % of full professional effort | 30% (20–50%) | 10–100% | |

| HIV clinical effort as % of all clinical effort | 75% (40–90%) | 5–100% | |

| Perception of HIV patient caseload | |||

| Proportion that are depressed | 30% (20–50%) | 10–80% | |

| Proportion of depressed that are being treated | 50% (40–71%) | 10–100% | |

| Proportion of treated that are being treated by HIV provider | 50% (20–80%) | 0–100% | |

| Very or extremely confident | |||

| Prescribing an initial antidepressant | 42 (59.1) | ||

| Changing or augmenting antidepressants | 10 (14.3) | ||

| Treating depression is part of role | 55 (77.4) | ||

Providers' median estimate of the proportion of their HIV caseload that was depressed was 30% (range: 10–80%; IQR: 20–50). Providers' median estimate of the proportion of their depressed HIV caseload that was receiving any depression treatment was 50% (range: 10–100%; IQR: 40–71%). HIV providers estimated that they were the primary source of depression treatment for 50% (median) of their patients who were receiving any depression treatment (range: 0–100%; IQR: 20–80%).

Sixty percent of providers reported feeling very or extremely confident prescribing a first antidepressant, but only 14% were very or extremely confident going to second-line treatment (changing or augmenting an antidepressant). Seventy-eight percent of providers were very or extremely confident that treating depression was a part of their role, and 73% felt it was very or extremely appropriate to receive decision support around prescribing antidepressants from nonprescribing clinic personnel (e.g., social worker, psychologist, or nurse).

Depression treatment practices

Table 2 presents a quantitative summary of providers' self-reported depression treatment practices relative to evidence-based guidelines, and Table 4 presents representative quotes from the qualitative content analysis of providers' responses.

Table 4.

Representative Quotes Indicating Depression Treatment Practices

| Indicators | Quote |

|---|---|

| Identifying depression | |

| Assessing depression | “While I don't do a formal standardized questionnaire for my patients, I think I know the signs and symptoms to look out for, just by seeing people. Often times I just rely on things like that to see if they're depressed. And if I get that hint that they might be depressed, I just ask more specific questions.” |

| Initiating treatment | |

| Need for treatment | “… I think that if those symptoms are creating a change in the quality of life or affecting their activities of daily living, or certainly if they're impacting their ability to cooperate and participate in their medical care. I think that's an indication for treatment.” |

| “… .I think depending on how severe their depression appears to be …” | |

| Choice of treatment | “… it's very patient driven. I mean, you can't force a patient to do something, so if they don't want to take a medicine…then you can try the counseling route. Some people say they don't want to talk to anybody, and they're happier taking a pill.…it's almost completely guided by what the patient is willing to do.” |

| Adjust starting dose for interaction with ARVs | “… I will do like, I'll check drug interactions. So that I can tell them what to look out for, but I usually just start with the initial starting lowest dose. So I'm pretty conservative.” |

| Managing treatment | |

| Follow-up after treatment initiation | “… ideally it would be two weeks into it and again at four weeks, but I think in reality maybe just at four weeks.” |

| “So I always try to schedule them back within a month and if they're severely depressed, maybe sooner. Whether or not they come back is a different issue, but I do schedule them.” | |

| Assessing effectiveness | “[I assess effectiveness] based on what they tell me, and what they look like when they come back. You know, if their affect improved, do they look brighter …” |

| When to titrate | “[Increase dose based on] inadequate resolution of symptoms, such as depressed mood, interest in activities, still issues with functional impairment, based on the depression. ….” |

| How high to titrate | “I just look in the standard Pharmacopoeia [which] usually gives you a max dose and I will titrate up to that max dose. Every antidepressant is different on that dose.” |

| Changing antidepressants | “I guess if they're having an adverse effect on the first one I've tried, or it seems like they're not making progress and we're getting to doses that I'm uncomfortable with then we'll switch.” |

Assessing depression

National guidelines recommend using a standardized measure to routinely assess all patients for depression. Overall, 31% of providers reported that they routinely assess patients for depression, with 12% using a standardized measure, and 19% using their own questions or observations. Content analysis indicated that providers primarily relied upon patient self-report, signs, and symptomatology, such as poor eye contact, being emotionless or disheveled, crying, slow speech, and change in weight. With a patient the provider had known for many years, the provider might recognize depression as soon as she entered the exam room because of these signs and symptoms. These initial observations might lead the providers to follow up on more nuanced symptoms of depression, including a change in appetite, guilt, mood, anhedonia, insomnia, fatigue, and libido dysfunction.

Few providers (12%) reported use of standardized measures or assessments. One provider reported using a standardized measurement to determine the severity of depression only after noticing signs and symptoms. Various screening methods were mentioned. Among those identifying any method, most referred to the “SIGECAPS” mnemonic device (an acronym of the core symptoms of depression) (n=6), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (n=3).

While many providers acknowledged that screening instruments were the best way to assess depression, most preferred a “free-flowing” method to assess depression, starting with general questions such as “How is your mood” or “How is life?”, leading to more specific questions such as “Are you able to sleep well?,” “Has there been a change in your appetite?,” “Are you able to concentrate at work?,” and “Do you still enjoy social activities?”

Need for treatment

National guidelines recommend that the decision to treat a depressive illness should be informed by the outcome of a standardized measure in conjunction with clinical assessment of severity and related factors. Two-thirds of providers reported using a clinical assessment of severity, with or without a standardized measure, to determine need for treatment. Seven percent initiated treatment only when asked by the patient, and 24% reported no systematic approach to determining need for treatment. Most providers said that they would wait a few weeks before initiating treatment if patients reported situational depression such as loss of a job, financial concerns, or death in family, or if the provider felt the depression was mild or temporary. Some providers also elicited patient input into a discussion about depression treatment. Some patients would ask for treatment, while others denied that they had depression. Most providers said they always assessed patients' willingness to take antidepressants, since many patients felt it was just “another pill to take” and would increase medication and cost burden.

Choice of treatment

National guidelines recommend that once need for treatment is determined, the specific treatment plan (counseling, medication, or both) should be informed by factors such as previous treatment experiences, severity of symptoms, and patient preference. Approximately half of providers reported that they consider such factors when developing a depression treatment plan, whereas 44% reported no systematic criteria. Although providers expressed a preference for medication therapy, most were not opposed to psychotherapy. For mild depressive episodes, cognitive behavioral therapy was often suggested before pharmacological management. Pharmacological management was encouraged when symptoms began to interfere with the patient's quality of life, including work, relationships, sleep, appetite, and health management. Many providers said they would recommend a form of behavioral therapy in conjunction with or prior to prescribing medication. Providers also described cost and previous treatment successes as guides for antidepressant selection.

Adjusting starting dose to account for interactions with ARVs

Due to the potential for some antiretrovirals to increase circulating antidepressant levels, HIV-specific treatment guidelines recommend using lower starting antidepressant doses. In our sample, one-third of providers reported adjusting antidepressant starting doses to account for the patient's ARV regimen, while two-thirds did not. Responses suggest that most providers were unaware of this recommendation. However, some providers reported different approaches depending on the class of antidepressant. For example, one provider stated, “generally I do not adjust if prescribing an SSRI or [citalopram] because of the [low] chance of…side effects.” Of the providers who reported that they did adjust antidepressant starting doses, they did so by referring to pharmaceutical reference texts or the pharmacist on service.

Follow-up after treatment initiation

National guidelines recommend that providers follow up with patients within 2 weeks of initiating an antidepressant regimen to assess for increased suicidal thoughts and to address any side effects that may have emerged, and within 4 weeks to assess response to treatment. Fourteen percent of providers reported scheduling phone or in-person follow-up with patients within 2 weeks of starting a new antidepressant regimen, and 38% followed up within 4 weeks. Fifteen percent of providers did not follow up until the next regularly scheduled clinic appointment (normally every 3–6 months for HIV care). Providers reported considering the severity of the patient's depression, patient access to the clinic, and contact with mental health providers when deciding on follow-up. Patients with more severe depression were followed up sooner than patients with milder depression. However, as one provider stated, “a patient who is that depressed would probably be referred to a mental health provider who has more skills and training to treat the patient.” Despite in-person follow-up barriers, many providers felt it was still important to offer support after initial diagnosis. One provider stated “it's important to let the patient see you are emotionally invested in their well-being.”

Assessing response

National guidelines recommend measuring symptoms systematically to assess response. About two-thirds of providers asked about symptoms in some fashion to assess effectiveness, although few (9%) reported using a standardized measure to do so. Most providers reported starting the conversation with “How are you doing” or “How you are feeling?” In addition to patient feedback, providers also mentioned reviewing the symptoms the patient had at initial presentation. Although providers often referred to initial signs and symptoms, very few providers said they actually used a measurement tool to compare to baseline when assessing for response. Twenty-six percent reported relying on the patient to report changes in symptoms and whether the treatment is working. Seven percent had no method to assess response.

When and how high to increase dose

National guidelines recommend systematic assessment of response and tolerability to guide antidepressant dose changes, with doses being increased until full response is achieved, side effects become unsupportable, or the maximum dose is reached. Approximately two-thirds of providers reported increasing doses based on formal or informal assessments of response and/or tolerability, 22% increased doses when asked by the patient, and 16% had no systematic criteria for dose adjustment. One provider acknowledged being taught to measure symptoms objectively but preferred informal discussion with the patient. All providers who adjusted doses said they waited at least 4–6 weeks before increasing a dose. At follow-up, providers normally reviewed the symptoms the patient had at onset; if the symptoms were still present and side effects were tolerable then a provider would increase the dose. One provider stated, “It's based on whether the patient has had an adverse response…If they have some [positive] response then I think that's a good sign to increase the amount.”

About half of the providers (48%) said they would titrate to the maximum recommended dose if needed, with guidance from product literature or pharmaceutical texts. Forty-five percent said they would not titrate up to the maximum dose, and 7% reported never increasing from a starting dose.

Changing antidepressants

According to national guide-lines, before changing to a new antidepressant, the original antidepressant should be given a trial of adequate duration (6–8 weeks) and dose (moderate to high dose) unless the patient develops side effects that cannot be satisfactorily addressed. Eighty-two percent of providers reported considering response and/or tolerability when considering switching the depression treatment plan, but only 18% ensured that the original antidepressant had been given an adequate trial. The most common reasons that providers offered for changing an antidepressant was if it “did not work” (duration and dose unspecified) or the patient was not tolerating the medication. Only 18% described ensuring an adequate trial of an antidepressant before switching to a different medication. Most providers reported feeling comfortable managing one medication switch, but subsequently preferred to refer to someone with more specific expertise.

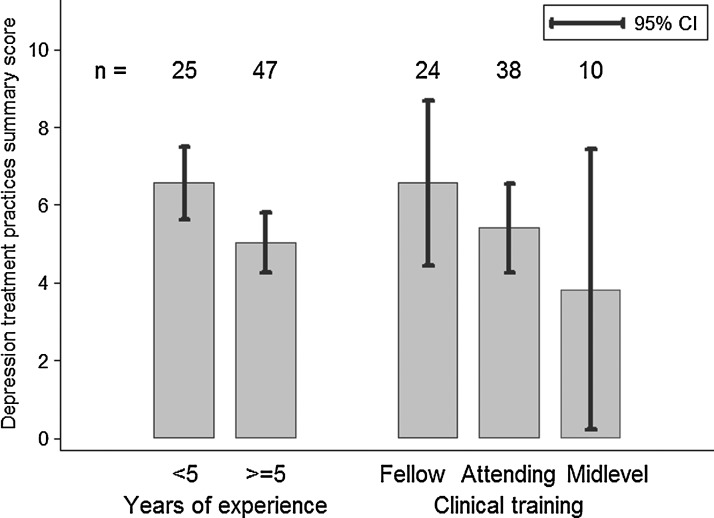

Difference by years of clinical experience

For several practice guidelines, greater adherence was reported by providers with <5 years of experience than by those with ≥5 years of experience, although most differences were not statistically significant in this small sample. Practice guidelines with at least a 10 percentage point difference indicating greater reported adherence among those with <5 years of clinical experience included following up within two weeks of initial prescription (20% vs. 9%, p=0.14), measuring symptoms systematically to assess efficacy (20% vs. 2%, p=0.13), basing dose adjustment decisions on assessment of response and tolerability (44% vs. 32%, p=0.4), using the full FDA dosing range (54% vs. 40%, p=0.49), and ensuring an adequate trial before switching (29% vs. 11%, p<0.01).

An exploratory factor analysis of the nine indicators of depression treatment practice supported a single factor solution (eigenvalue for first factor: 1.83; eigenvalue for second factor: 0.50), with eight of nine items positively weighted on the first factor. The exception was adjustment of antidepressant starting doses to account for ARV interactions, which had a near-null weight on both the first and second factors. We therefore calculated a “summary best-practices score” of depression treatment using the estimated factor loadings on the eight positively weighted indicators and rescaled the resulting score to range from 0–10.

Those with <5 years of experience had a higher summary best practices score than those with ≥5 years of experience (6.6 vs. 5.0 on a 0–10 scale, p=0.05) (Fig. 1). A similar pattern emerged when comparing MD-fellows and MD-attendings, with a higher proportion of MD-fellows reporting adherence to best-practices guidelines for a number of indicators and MD-fellows having a higher summary best practices score (6.5 vs. 5.4, p=0.21). Midlevel providers (NPs and PAs) had a lower summary best-practices score than either attendings or fellows, although the number of midlevels in this sample was small. Summary scores did not differ by site (site-specific means of 5.7, 5.5, and 5.5, p=0.97).

FIG. 1.

Depression treatment practices summary score by provider years of experience and level of clinical training.

Discussion

Very few data exist on the practices of nonmental health providers in treating depression. There is a growing literature on the high prevalence and negative consequences of co-morbid depression in HIV1,4,14 as well as other chronic illnesses such as heart disease15,16 and diabetes,17,18 suggestive evidence that treating depression may improve HIV adherence and outcomes,19 and a growing recognition that existing mental health resources are inadequate to meet the needs of these populations. Recent initiatives have sought to integrate depression treatment with primary care and chronic disease management,8,20–22 and promising models exist for the provision of mental health care for HIV-infected patients,9,23 yet gaps remain in mental health care coverage and access.20

In this sample of 72 HIV providers at three academic medical centers, providers demonstrated an appreciation of the significant burden of depression in patients presenting for HIV care. Providers' estimates of depression prevalence in their caseload were fairly close to estimates of depression prevalence in HIV patients nationally24 as well as at these specific clinics.25–27 Providers' estimates that approximately half of their depressed patients were receiving treatment were also quite close to national estimates suggesting that about half of those with depression are not being treated.3,24,28

Although variability was evident in providers' approaches to identifying depression and developing and implementing a treatment plan, all providers were taking steps to address depression either by referral or treatment initiation. In general, reported practices of these providers follow the spirit if not every detail of best practices and practice guidelines: assess symptoms, prescribe treatment, monitor improvement, adjust treatment if response is not adequate, and refer when appropriate. However, specific discrepancies between guidelines and reported practices were apparent. Importantly, these discrepancies are readily addressable with education and support.

National guidelines recommend that all patients be screened on a routine basis utilizing a validated measure of symptomatology.10 In general, the providers in this study responded to symptoms that were obvious during the patient encounter, but few providers endorsed using a standard measure when depression was suspected, and few providers reported screening all patients regardless of signs of depression. Extensive evidence suggests that as many as half of depressive illnesses go unrecognized in primary and nonpsychiatric specialty care in the absence of screening,3,28 with subsequent failure to address the depression and mitigate its impact on chronic disease management.

Depression screening alone is not sufficient to improve outcomes.29,30 It is only the first in a critical series of steps to successfully treat depression. Initiation of treatment is a necessary next step. When initiating treatment, the providers in this study largely relied on clinical judgment and patient preference. This approach is directly in line with best practices that identify patient preference and clinical severity as key determinants in whether to initiate psychotherapy or medication. A small minority of providers preferred immediate referral to a mental health professional, an option necessarily limited by resources and access. While most providers were comfortable prescribing an initial antidepressant, the majority were unaware of recommendations to adjust antidepressant starting doses based on a patient's ARV regimen.

Follow-up and monitoring of depression treatment is often limited by the realities of busy clinic settings. Contact within 2 weeks of initiating antidepressant medication is a target challenging to meet in any busy clinic. STAR*D, IMPACT, and other trials of collaborative care approaches have demonstrated that support staff can successfully assist the provider in meeting this goal.7,20,21 Care managers who can use validated instruments to assess systematically suicidality, treatment-emergent side effects, and treatment response can provide critical input while minimizing provider burden. Timely and brief communication between care manager and provider has intuitive value to meet the treatment and time needs of patients and providers while aligning practices with national guidelines.

Care managers can also provide guidance in decisions around a second treatment approach (e.g., switching or augmenting medications) if an adequate trial of the first treatment approach is not successful. Indeed, data from STAR*D suggest that only one-third of depressed patients are likely to respond to the first adequate trial, although two-thirds are likely to achieve remission within two or three carefully monitored adequate trials.31 Providers in this study were generally comfortable initiating one antidepressant but markedly less comfortable with switching or augmenting antidepressants.

Even with such care manager support, it is unreasonable to expect that nonmental health providers will be able to meet the needs of all depressed patients in their care. In the STAR*D trial, one-third of patients with depression did not achieve remission after up to three carefully monitored adequate treatment trials.31 Trained and supported care managers can help providers efficiently differentiate between patients whose depression can likely be successfully addressed in their care and patients whose presentations suggest immediate referral, such as those with prior depression treatment resistance, complicating psychiatric co-morbidity (e.g., mania or psychosis), or serious suicidality.

In this sample, providers who had been treating HIV patients for <5 years were more likely to report best-practice principles of depression treatment and, on average, had higher best-practice summary scores than providers who had been treating HIV patients for 5 years or more. Similarly, MD-fellows reported higher concordance with best practices than MD-attendings. This finding may reflect closer proximity to general medical training including depression management during medical school and residency, or it may reflect recent shifts in medical curricula toward broader integration of training in depression treatment and specifically measurement-based depression management.

This study makes a unique contribution to the literature on the treatment of depression in HIV patients, providing a detailed comparison of HIV providers' self-reported depression identification and treatment practices to national evidence-based guidelines. While research has highlighted the gap between depression prevalence and treatment among HIV patients,3,24,32 we identified no other published studies that detail HIV providers' standard approaches to depression screening, treatment choice, antidepressant initiation, assessment of efficacy, dose adjustment, and treatment switches in the context of routine HIV clinical care.

Interpretation of this study's results is limited by the fact that practices were measured by provider self-report, and that provider reports were not verified through medical record review. Social desirability may have influenced providers to give optimistic assessments of their actual treatment practices. This may result in an overestimation of the concordance of providers' practices with evidence-based guidelines. Further research would benefit from assessing actual practices as reflected in observations or medical records. In terms of external validity, the three sites involved are all in the U.S. Southeast, in mid-sized population centers with large rural catchment areas, and at academic institutions. Generalizability is limited due to regional differences in practice realities (e.g., availability of mental health professionals with subsequent greater or lesser involvement of HIV providers in depression management). Even within sites, variability was high with regard to access to mental health care. In-clinic or on-site mental health referral services varied by site as did payer mix (i.e., state-provided insurance, private insurance, self-pay). These differences could affect attitudes and practices, for example, as providers might provide greater depression care at clinics where services were less readily available or where payer mix did not favor easy referral to specialty care. In summary, HIV providers in the present study demonstrated a clear understanding of the importance of depression in their patients. Most providers were managing depression in at least some of their patients, but their adherence to best-practices treatment as described in national guidelines was variable. While all providers receive some training in management of depression, HIV providers are not trained or expected to provide a full spectrum of psychiatric care. However, the present study suggests three reasonable targets for improvement that could bring depression treatment practices by HIV providers closer to national guidelines. The first is clinical or structural support of routine screening for depression to address the large proportion of cases that go unrecognized in medical care. The second target is education of providers in a few key areas of depression management: adjusting antidepressant doses to account for interactions with antiretrovirals, measuring treatment response systematically, and ensuring an adequate trial of a given medication before switching or referring. The third is support from care managers to assist with the more time-intensive or complex aspects of depression treatment, including regular monitoring of side effects and response. Models of collaborative care and measurement-based care have successfully addressed these gaps in research settings in both primary and specialty medical care.7,20,21 Efforts to implement these models in more widespread clinical practice could pay large dividends for a modest investment in terms of increasing the quality of depression care and improving mental health and HIV outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant (R01MH086362; PIs: Brian Pence, Bradley Gaynes) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We would like to thank the participating HIV providers for participating in the interviews. We acknowledge the following members of the study staff who conducted interviews: R. Scott Pollard, Katya Roytburd, Allison Sanders, and Riddhi Modi. Special thanks to Jordan Akerley and Julie O'Donnell for transcribing the interviews. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the Duke Center for AIDS Research, NIAID grant P30-AI064518. NMT is supported by Grant U01 AI069484 from NIAID of the NIH. BWP is an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bing EG. Burnam MA. Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciesla JA. Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asch SM. Kilbourne AM. Gifford AL, et al. Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV: Who are we missing? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:450–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez JS. Batchelder AW. Psaros C. Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: A review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:181–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White House. Washington, DC: White House; 2010. [Dec 4;2012 ]. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaynes BN. Rush AJ. Trivedi MH, et al. Primary versus specialty care outcomes for depressed outpatients managed with measurement-based care: Results from STAR*D. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grypma L. Haverkamp R. Little S. Unutzer J. Taking an evidence-based model of depression care from research to practice: Making lemonade out of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JL. Gaynes BN. McGuinness T. Modi R. Willig J. Pence BW. Treating depression within the HIV “Medical Home”: A guided algorithm for antidepressant management by HIV clinicians. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26:647–654. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Third. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Depression and mania in patients with HIV/AIDS. http://www.hivguidelines.org/clinical-guidelines/hiv-and-mental-health/depression-and-mania-in-patients-with-hivaids/ [Dec 4;2012 ]. http://www.hivguidelines.org/clinical-guidelines/hiv-and-mental-health/depression-and-mania-in-patients-with-hivaids/

- 12.Graneheim UH. Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Ed Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harman HH. Modern Factor Analysis. 3rd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whetten K. Reif S. Whetten R. Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental health, distrust, and stigma among HIV-positive persons: Implications for effective care. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:531–538. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817749dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippi G. Montagnana M. Favaloro EJ. Franchini M. Mental depression and cardiovascular disease: A multifaceted, bidirectional association. Sem Thrombosis Hemostasis. 2009;35:325–336. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1222611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush DE. Ziegelstein RC. Patel UV, et al. Post-myocardial infarction depression. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2005;123:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson RJ. Freedland KE. Clouse RE. Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Groot M. Anderson R. Freedland KE. Clouse RE. Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:619–630. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bottonari KA. Tripathi SP. Fortney JC, et al. Correlates of antiretroviral and antidepressant adherence among depressed HIV-infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26:265–273. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon WJ. Lin EH. Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pyne JM. Fortney JC. Curran GM, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:23–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis SE. Gaynes BN. Morrissey JP. Vinson N. Ellis AR. Domino ME. Generalist care managers for the treatment of depressed medicaid patients in North Carolina: A pilot study. BMC Family Pract. 2007;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reif SS. Pence BW. Legrand S, et al. In-Home mental health treatment for individuals with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26:655–661. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pence BW. O'Donnell JK. Gaynes BN. Falling through the cracks: The gaps between depression prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and response in HIV care. AIDS (London, England) 2012;26:656–658. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283519aae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pence BW. Miller WC. Whetten K. Eron JJ. Gaynes BN. Prevalence of DSM-IV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the Southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219773.82055.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence ST. Willig JH. Crane HM, et al. Routine, self-administered, touch-screen, computer-based suicidal ideation assessment linked to automated response team notification in an HIV primary care setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1165–1173. doi: 10.1086/651420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whetten K. Reif S. Swartz M, et al. A brief mental health and substance abuse screener for persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19:89–99. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell AJ. Vaze A. Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374:609–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thombs BD. Coyne JC. Cuijpers P, et al. Rethinking recommendations for screening for depression in primary care. CMAJ. 2012;184:413–418. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Connor EA. Whitlock EP. Beil TL. Gaynes BN. Screening for depression in adult patients in primary care settings: A systematic evidence review. Ann Internal Med. 2009;151:793–803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaynes BN. Warden D. Trivedi MH. Wisniewski SR. Fava M. Rush AJ. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1439–1445. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Israelski DM. Prentiss DE. Lubega S, et al. Psychiatric co-morbidity in vulnerable populations receiving primary care for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2007;19:220–225. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]