Abstract

There are reports of increased sexual risk behaviors in the HIV-positive population since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Little is known about the effects of the case management (CM) program and HAART on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in Taiwan. HIV-positive subjects, who visited the outpatient clinics of Taoyuan General Hospital between 2007 and 2010, were enrolled. A total of 574 subjects and 14,462 person-months were reviewed. Incident STDs occurred in 104 (18.1%) subjects, and the incidence rate was 8.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.1–10.5) per 100 person-years (PY). For men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexual men and women, and injection drug users (IDU), 19.4 per 100 PY(95% CI, 15.7–24.0), 3.5 per 100 PY (95% CI, 1.4–7.3), and 1.1 per 100 PY (95% CI, 0.4–2.4) of STDs were noted, respectively; (MSM versus IDU and MSM versus heterosexual subjects, p<0.000001; heterosexual subjects versus IDU, p=0.061). Syphilis (59.6%) was the most common STD. Regular CM and no HAART (hazard ratio, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.14–5.84; p=0.02) was significantly associated with STDs in MSM. Though this retrospective study might underestimate the incidence of STDs and not draw the conclusion of causality, we concluded that the CM program and HAART are associated with lower acquisition of STDs in the Taiwanese HIV-positive population.

Introduction

Since 1997, the Taiwanese government has provided free access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), thereby considerably improving the health status and survival rate among people infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),1 as in many Western countries.2 Currently, coverage with HAART is quite high in Western countries.3 Moreover, because of the compelling evidence for treatment as a preventive measure, especially among heterosexual discordant couples,4–7 Taiwan's government has promoted HAART aggressively. Thus, 50% of reported HIV cases are currently treated by using HAART.8 However, there are many concerns; for example, durable compliance in life-long treatment, subsequent antiretroviral resistance with poor adherence, and an increasing economic burden due to increasing time of survival among HIV-positive patients under HAART. In addition, several reports of increasingly risky sexual behaviors in the HIV-positive population in the post-HAART era have been published.9–15 Therefore, the use of HAART for HIV prevention is facing significant challenges.

HIV-positive patients who subsequently develop sexually transmitted infections (STDs) likely practice risky sexual behaviors, potentially transmitting HIV to others. In addition, STDs increase HIV viral shedding in the genital tract, resulting in increasing HIV infection.16,17 A drug-resistant virus can emerge when patients do not adhere to HAART, leading to transmitted resistance and hindering the effect of preventive treatment.18,19

In Taiwan, a cross-sectional report revealed that 56% of HIV-positive patients, especially men who have sex with men (MSM), practiced unprotected sexual behavior.20 Other investigators in southern Taiwan showed that 17% of HIV-positive patients relapsed to sexual risk behavior after 1 year of enrollment in a case management (CM) program, and that the incidence for syphilis was 5.8 cases per 100 patient-years.21 A CM program is an integrative service that provides risk reduction counseling and assists HIV-positive patients in medical adherence; the programs were initiated by the Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan, and implemented by all designated hospitals in Taiwan. Like previous studies, the CM program providing education and counseling, condom use promotion, and behavioral modification, only moderately affected HIV prevention.21–23 Little is known about the effects of incorporation of CM and HAART on the incidence of STDs. Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to determine how HAART and CM programs are likely to influence the HIV epidemic. Thus, the aims of this study were to determine the incidence of STDs, and to predict risk factors for developing STDs, in an HIV-positive cohort in Taiwan.

Methods

Population and enrollment

Between January 2007 and December 2010, HIV-positive patients who visited the outpatient clinics of Taoyuan General Hospital, Taoyuan County, were invited to participate in the CM program as a case cohort. After initial individualized evaluation for risk behavior, performed by a well-trained case manager via face-to-face interview, all participants were asked to return for follow-up counseling and outpatient visits every 3 months. This counseling included a standardized interview, assessment of sexual behavior, and frequency of condom use. Information and education on safe sex were also provided by the case manager. In addition, physicians performed a physical examination and laboratory testing at the same time. HIV-positive patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <350 cells/μL, or who had developed HIV-associated illnesses or opportunistic infections, began HAART. The study was reviewed and certified by the institutional review boards of Taoyuan General Hospital, Department of Health (IRB No. TYGH98021, TYGH10016).

Clinical and laboratory diagnosis

We reviewed medical records for the new onset of primary or secondary syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydial urethritis, condyloma acuminata, amebic colitis/liver abscess, and other clinical diagnosis of STDs. Primary or secondary syphilis was defined as occurrence of chancre, condyloma latum, generalized skin rashes, or alopecia, and single rapid plasma reagin titer ≥1:8 or serum conversion ≥4-fold rise and positivity for Treponema pallidum hemagglutination. Neisseria gonorrhoeae was detected by analyzing a urethral culture or by performing polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Nongonococcal urethritis was confirmed by pyuria in urinalysis and negative bacterial culture or positive PCR for Chlamydia spp. New lesions of condyloma acuminata and the first episodes of herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2), were recorded. Invasive amebiasis was considered as an STD only among MSM. Amebic colitis was diagnosed by clinical symptoms of diarrhea, stool wet mount yielding trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica/dyspar, and positive PCR reaction for E. histolytica. Amebic liver abscess was diagnosed on the basis of clinical suspicion, sonography, and amebic antibody titers more than 1:16, or PCR positivity for E. histolytica from liver aspirates. Other STDs were defined on the basis of the diagnosis by physicians. Recurrence of syphilis, defined by a rise in rapid plasma reagin titer ≥4-fold; recurrence of condyloma acuminata, defined by the growth of lesions either at the same sites of previous lesions or at the different sites; recurrence of HSV-2 infection, defined by the reappearance of blisters, and re-infections of Chlamydia spp., gonococcus, or amebiasis were not analyzed as incident cases.

HIV-1/2 antibody testing was performed using microparticle enzyme immunoassay (HIV 1/2 gO, Abbott Diagnostic Division, IL, USA). Samples with positive results were run in duplicate sets, and results were confirmed by HIV-1 or HIV-2 Western blot assays (New LAV Blot-I and II, Bio-Rad Fugirebio Inc, Tokyo, Japan). We also evaluated CD4+ T-cell counts by using flow cytometry (Coulter® Epics XL™, Beckman Coulter, CA) and HIV viral loads (Cobas® AmpliPrep/Cobas® TagMan HIV-I test, Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Branchburg, NJ) for all HIV-positive subjects every 3–6 months.

Statistical analysis

Subjects who regularly kept their appointments (every 3 months) to visit outpatient clinics were defined as regular CM cases. Subjects who missed outpatient appointments at least twice a year were defined as irregular CM cases. Subjects who had not followed up for >6 months were censored.

Subjects who contracted any type of STD after 3 months of enrollment were considered incident cases. “STDs after HAART” was determined when the time between the start of HAART and the date of STD diagnosis was greater than the incubation period of the STD.

Exposure to sexual risk behavior was defined as using condom inconsistently (often, seldom, or never) during anal/vaginal intercourse in the 3 months prior to disease or censoring. Recreational drug usage including 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, amphetamine, ketamine, marijuana, and flunitrazepam were recorded during follow-up visits. Injected heroin used by injection drug users (IDU) was excluded. CD4+ T-cell counts and HIV viral loads in the 3 months prior to disease or censoring were also recorded.

Demographic data are presented as the means (±standard deviation, [SD]) for continuous variables and as a percentage for discrete variables. The chi-square test was used to evaluate the distribution of categorical data. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Duncan procedure was used for comparisons between more than two groups for continuous variables. Poisson distribution was used for comparisons of the STD incidence between two groups and estimation of 95% of confidence intervals (CIs) of incidence rates. Covariates with a p value of <0.2 on univariate analysis were then analyzed using multivariate analysis; estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were calculated. Cox proportional hazards models were applied to identify predictors of the incident STDs, and to assess the adjusted HRs of HAART and CM after controlling for gender, age, CD4+ T-cell levels and HIV viral load levels. Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank tests were also applied for comparison between different groups. Statistic analysis was conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC). Kaplan-Meier analyses were graphed using SigmaPlot version 11.0 (Systat Software Inc. San Jose, CA). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 574 subjects enrolled. The male to female ratio was 505:69. The average age was 33.9±9.3 (mean±SD) years. A total of 14,462 person-months were observed, and the mean duration of follow-up was 2.10±1.36 years. Among enrolled subjects, 40.6% were MSM, 47.4% reported IDU, and the remaining 12% reported heterosexual behavior as the primary cause of HIV infection. Two hundred and seventy-four subjects (47.7%) had regular CM during the study periods, while the remaining 300 subjects (52.3%) did not attend CM programs regularly. Two hundred and sixty-seven (46.5%) subjects had HAART, and 189 (70.7%) of these regularly attended CM programs. These data are summarized in Table 1. Comparing three risk categories (MSM, heterosexual, IDU), MSM tended to be younger; heterosexual subjects tended to be older and were more likely to have lower CD4+ T-cell counts and be on HAART; and IDU tended to have detectable HIV viral load, and were less likely to be in regular CM and on HAART. Among IDU, only 19.1% adhered to the case management program regularly, and only 24.3% had HAART, much different from MSM (73.8% of CM regularity, and 60.5% of HAART, p<0.001, respectively) and heterosexual men/women (72.5% of CM regularity, and 86.9% of HAART, p<0.001, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 574 HIV-Positive Subjects Who Were Recruited for the Case Management Program

| Characteristics | All subjects, n (%) | Men who have sex with men, n (%) | Heterosexual men/women, n (%) | Injection drug users, n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 574 (100) | 233 (40.6) | 69 (12) | 272 (47.4) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 505 (88) | 233 (100) | 55 (79.7) | 217 (79.8) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 69 (12) | 0 (0) | 14 (20.3) | 55 (20.2) | |

| Mean age, years±SD | 34.0±9.3 | 30.9±8.9 | 40.2±13.1 | 35.2±7.6 | <0.0001c,d |

| Age level (years) | |||||

| <25 | 78 (13.6) | 57 (24.5) | 7 (10.1) | 14 (5.1) | <0.0001 |

| 25–29 | 121 (21.1) | 59 (25.3) | 9 (13) | 53 (19.5) | |

| 30–34 | 135 (23.5) | 49 (21) | 11 (15.9) | 75 (27.6) | |

| 35–39 | 98 (17.1) | 31 (13.3) | 11 (15.9) | 56 (20.6) | |

| 40–49 | 111 (19.3) | 32 (13.7) | 16 (23.2) | 63 (23.2) | |

| ≥50 | 31 (5.4) | 5 (2.1) | 15 (21.7%) | 11 (4) | |

| HIV viral load level (copies/ml) | |||||

| <400 | 212 (37.1) | 108 (46.4) | 49 (71) | 55 (20.2) | <0.0001 |

| 400–10,000 | 196 (34.3) | 41 (17.6) | 8 (11.6) | 147 (54.0) | |

| 10,000–100,000 | 135 (23.6) | 61 (26.1) | 11 (15.9) | 63 (23.1) | |

| >100,000 | 29 (5.1) | 22 (9.4) | 1 (1.4) | 6 (1.8) | |

| CD4+ T-cell level (cells/ul) | |||||

| <200 | 56 (9.8) | 25 (10.7) | 13 (18.8) | 18 (6.6) | 0.040 |

| 200–350 | 163 (28.5) | 59 (25.3) | 21 (30.4) | 83 (30.5) | |

| 350–500 | 168 (29.4) | 74 (31.7) | 13 (18.8) | 81 (29.7) | |

| >500 | 185 (32.3) | 74 (31.8) | 22 (31.9) | 89 (32.7) | |

| Sexual behaviors | |||||

| Sexual riska | 92 (16.1) | 35 (15) | 11 (15.9) | 46 (16.9) | 0.651 |

| No sexual risk | 482 (83.9) | 198 (85) | 58 (84.1) | 226 (83.1) | |

| Condom usage in 3 months prior to disease or censoring | |||||

| Always | 482 (83.9) | 198 (85) | 58 (84.1) | 226 (83.1) | 0.212 |

| Often | 58 (10.1) | 28 (12) | 7 (10.1) | 23 (8.4) | |

| Seldom | 22 (3.8) | 5 (2) | 2 (2.9) | 15 (5.5) | |

| Never | 12 (2.1) | 2 (1) | 2 (2.9) | 8 (2.9) | |

| Recreational drug usageb | |||||

| Yes | 243 (42.3) | 53 (22.7) | 14 (20.2) | 176 (65) | <0.0001 |

| No | 331 (57.7) | 180 (77.3) | 55 (79.8) | 96 (35) | |

| Case management | |||||

| Regular | 274 (47.7) | 172 (73.8) | 50 (72.5) | 52 (19.1) | <0.0001 |

| Irregular | 300 (52.3) | 61 (26.2) | 19 (27.5) | 220 (80.9) | |

| HAART | |||||

| Yes | 267 (46.5) | 141 (60.5) | 60 (86.9) | 66 (24.3) | <0.0001 |

| No | 307 (53.5) | 92 (39.5) | 9 (13.1) | 206 (75.7) |

Sexual risks: often, seldom, never use of condom during anal/vaginal sex in 3 months prior to disease or censoring. bRecreational drugs: 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, amphetamine, ketamine, marijuana, and flunitrazepam. Heroin excluded.

Duncan procedure for men who have sex with men compared with heterosexual men/women; dDuncan procedure for men who have sex with men compared with injection drug users.

HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; SD, standard deviation.

Incidence of STDs

Incident STDs occurred in 104 (18.1%) subjects, and the incidence of any STD was 8.6 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 7.1–10.5), including 19.4 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 15.7–24.0) for MSM, 3.5 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 1.4–7.3) for heterosexual men and women, and 1.1 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 0.4–2.4) for IDU (MSM versus IDU and MSM versus heterosexual subjects, p<0.000001; heterosexual subjects versus IDU, p=0.061). Syphilis (59.6%), condyloma acuminata (26.9%), gonorrhea (5.8%), nongonococcal urethritis (2.9%), and invasive amebiasis (1.9%) were the most common newly acquired STDs. Recurrent infections (62.5%, 65/104) were not uncommon among these STD cases. A total of 328 episodes of STD were recorded, including syphilis (62.8%), condyloma acuminata (24.7%), nongonococcal urethritis (3.4%), gonorrhea (3.4%), and invasive amebiasis (2.1%).

Predictors of incident STDs

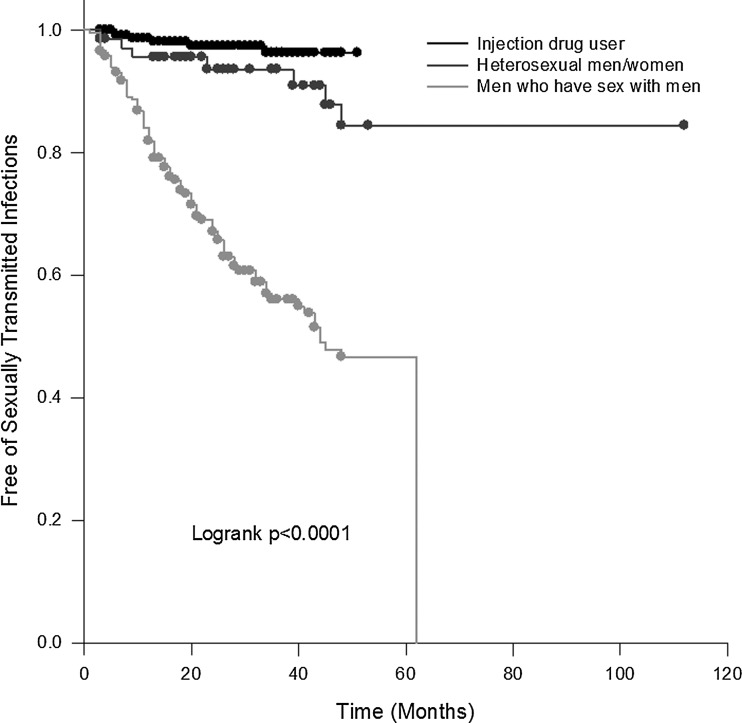

Incident STDs occurred in 11.5 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI, 8.9–15.0) among patients without HAART, and in 6.3 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI, 4.6–8.5) among patients after HAART (p=0.037). Strikingly, incident STDs occurred in 5.5 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI, 3.7–7.8) among patients without regular CM, but in 11.4 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI, 9.0–14.4) among patients with regular CM (p=0.025). To determine why patients with regular CM have a higher incidence of STDs, we performed further analysis using Cox proportional hazards modeling (Table 2). Subjects who developed incident STDs were more likely to have regular CM and no HAART, high viral load (>100,000 copies/mL), and to be MSM. MSM have the highest probability (log-rank p<0.001) of contracting STDs, compared to heterosexual subjects and injected drug users during the observational periods (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Model for the Factors Associated with Developing Incident Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) Among 574 HIV-Positive Subjects, Adjusted by Sex, Age, and CD4+ T Cell Counts

| Variables (numbers) | Cases of STDs (%) | Incidence of STDs, per 100 person -years (95% CI) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk category | ||||

| Men who have sex with men (233) | 91 (39.1) | 19.4 (15.7–24.0) | 16.12 (6.09–42.62) | <0.001 |

| Heterosexual (69) | 7 (10.1) | 3.5 (1.4–7.3) | 3.93 (1.18–13.13) | 0.0262 |

| Injection drug user (272) | 6 (2.2) | 1.1 (0.4–2.4) | 1.00 | |

| HIV viral load, copies/ml | ||||

| >100,000 (29) | 14 (48.3) | 38.0 (20.8–63.9) | 2.94 (1.22–7.12) | 0.0166 |

| 10,000–100,000 (135) | 37 (27.4) | 15.1 (10.7–20.8) | 1.65 (0.76–3.56) | 0.2045 |

| 400–10,000 (196) | 11 (5.6) | 3.0 (1.5–5.3) | 0.79 (0.34–1.82) | 0.5752 |

| <400 (212) | 34 (16) | 6.3 (4.4–8.7) | 1.00 | |

| CM and HAART | ||||

| Regular CM and no HAART (84) | 39 (46.4) | 23.9 (17.0–32.5) | 2.54 (1.17–5.52) | 0.0179 |

| Irregular CM and no HAART (222) | 20 (9.0) | 5.6 (3.4–8.6) | 1.95 (0.84–4.55) | 0.1228 |

| Irregular CM and HAART (78) | 10 (12.8) | 5.2 (2.5–9.6) | 0.72 (0.30–1.77) | 0.4766 |

| Regular CM and HAART (190) | 35 (18.4) | 7.1 (4.9–9.8) | 1.00 | |

CM, case management; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

FIG. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the development of incident sexually transmitted diseases, stratified by HIV risk categories.

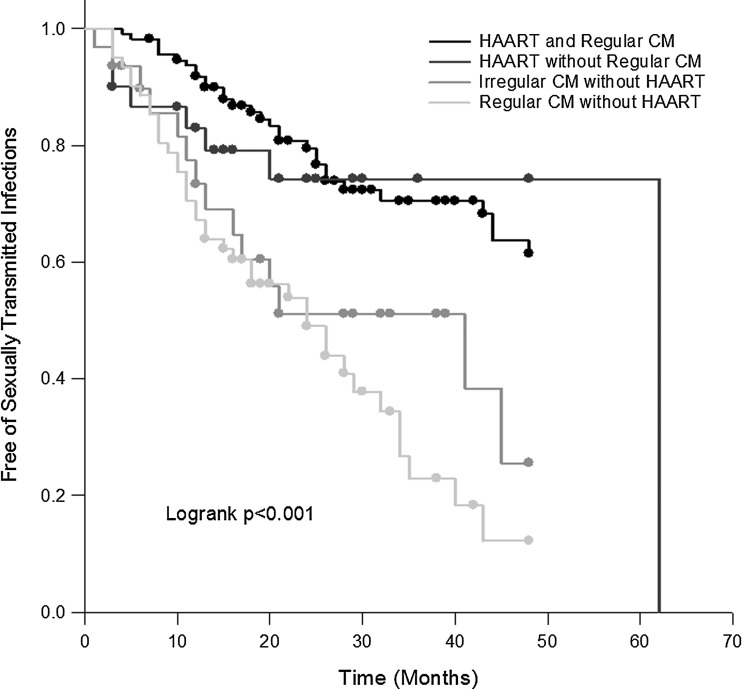

Since MSM are at the greatest risk of developing STDs, sub-analysis was performed among these 233 MSM. Cox proportional hazards modeling revealed that compared to regular CM and HAART, regular CM and no HAART was a significant predictor of developing new STDs during follow-up among MSM (HR 2.58, 95% CI, 1.14–5.84; p=0.02) after adjusting for age, CD4+ T-cell count, and HIV viral load (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Recreational drug consumption (HR 1.13, 95% CI, 0.69–1.86; p=0.64) and <75% chance of condom usage in the 3 months prior to disease or censoring (HR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.32–1.30; p=0.22) were not significant.

Table 3.

Cox Proportional Hazard Model for the Factors Associated with Developing Incident Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Among 233 HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men, Adjusted by Age, and CD4 T+ Cell Counts

| Variables (number) | Cases of STD (%) | Incidence of STD, per 100 person -years (95% CI) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV viral load, copies/ml | ||||

| >100,000 (22) | 12 (54.5) | 42.0 (21.7–73.5) | 2.41 (0.90–6.42) | 0.079 |

| 10,000–100,000 (60) | 34 (56.6) | 35.2 (24.5–48.9) | 1.36 (0.59–3.15) | 0.4684 |

| 400–10,000 (41) | 14 (34.1) | 16.2 (8.6–27.2) | 0.67 (0.27–1.66) | 0.3951 |

| <400 (108) | 30 (27.7) | 11.8 (8.0–16.9) | 1.00 | |

| CM and HAART | ||||

| Regular CM and no HAART (60) | 38 (63.3) | 39.7 (28.0–54.6) | 2.58 (1.14–5.84) | 0.0228 |

| Irregular CM and no HAART (31) | 14 (45.2) | 28.3 (15.5–47.6) | 1.70 (0.67–4.27) | 0.2634 |

| Irregular CM and HAART (30) | 8 (25.8) | 12.8 (5.5–25.2) | 0.83 (0.31–2.24) | 0.7089 |

| Regular CM and HAART (112) | 31 (27.6) | 11.8 (8.0–16.9) | 1.00 | |

CM, case management; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

FIG. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the development of incident sexually transmitted diseases among men who have sex with men, stratified by case management program (CM) and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

Discussion

In recent years, attempts to reduce the sexual risk of HIV, such as education and counseling, promoting condom use, and behavioral modification have been carried out aggressively in the Chinese society. Fan and associates24 reported that HIV infection was associated with syphilis among MSM in Beijing, China, and that syphilis control strategies such as changing social norms about condom use may have an impact on HIV prevention.24 Liao and colleagues25 noted that targeting the highly prevalent bisexual behavior with multiple sexual partners and unprotected sex in Shandong's gay community may have an influence on HIV transmission.25 Ko and associates21 also highlighted that 1 year after enrollment into the CM program in Tainan, Taiwan, 80% of the HIV-positive patients practiced safe sex.21 Unfortunately, the above efforts only moderately affect HIV prevention.21–23 The use of antiretroviral therapy reduces the HIV viral load in the blood and genital secretions, thus reducing the infectivity of HIV.26 Patients undergoing HAART have lesser risk of transmitting HIV to their serodiscordant partners, especially among heterosexual couples.4–7 Further, some studies reported that pre-exposure prophylaxis using antiretroviral agents reduced the risk of infection for both seronegative heterosexual partners of HIV-infected individuals and HIV-negative homosexual men with continuous risk of HIV exposure.27,28 These strategies seem promising in altering the HIV epidemic, but are under debate due to some observations of high-risk populations having low levels of risk perception,29 and HIV-positive patients increasing risky sexual behaviors in the HAART era.30–33

Previous studies have shown that under regular medical care, HIV-positive patients decrease their sexual risk behaviors by 30–55%,30,33 especially in the initial years following the discovery of their HIV status.30,31 In New York, people who had known their HIV-infected status for >5 years were more prone to sexual risk behaviors.32 In Amsterdam, HIV-positive MSM had 61% of increase of unprotected anal sex after 4 years of seroconversion.30 In Northern Taiwan, Chen and colleagues20 demonstrated that HIV status awareness for >11 years was accompanied by a 2-fold higher likelihood of practicing unprotected sexual behaviors.20 These findings indicate that risky sexual behaviors relapsed frequently, and there was no lasting effect on sexual behavior modification.20,30–33 Our study evaluated the effectiveness of CM programs in prevention of STDs. This study showed that HIV-positive MSM who regularly attended CM programs but had not initiated HAART had a significant risk associated with acquiring new STDs. The government-funded CM program provides one-on-one risk reduction counseling and reinforcement of safe sex behavior every 3 months. However, it was not effective unless HAART was incorporated.

Previous observational studies have shown that patients who were MSM,9 had higher CD4+ T-cell counts,21 and had received HAART,34 were more likely to practice unprotected sex. These studies showed that MSM tended to have multiple sexual partners, and were more likely to practice unprotected anal sex, and when HIV-positive patients experienced improved health after starting HAART, they resumed their risky sexual behaviors.9,21,30,34–35 However, other prospective studies have shown that sexual risk behaviors were either unchanged or decreased among HIV-positive patients after initiation of HAART.36–39 Comparisons between these studies are impossible, since assessment of self-reported risk behaviors is not comparable, due to recall bias for memories of different duration, or because of social desirability effects on self-reports of condom usage or multiple partners, for example. Hence, objective biological outcomes of sexual risk behaviors, like STDs, are more persuasive as surrogate markers. Studies of Kenyan female sexual workers demonstrated a trend (odds ratio 0.67, 95% CI 0.44–1.02, p=0.06) toward decreased STDs following initiation of HAART.39 Paralleling the previous report of Kenyan women,39 our 4-year observational study also showed that HAART was associated with a 60% reduction in hazard ratio for acquiring STDs. There are two implications of this finding: first, patients who had initiated HAART seem to pay more attention to modification and reduction of sexual risk behaviors; second, CM programs did not influence HIV-positive patients until the patients were on HAART.

It is also worth noting that patients with HIV viral loads >105 copies/mL tended to have a higher incidence of STDs in this study. It is believed that acquisition of STDs may increase HIV infectiousness,16,17 and such high viral loads make the HIV prevention campaign more difficult.

Some limitations of our study warrant discussion. First, this is a retrospective study, so randomization to the CM program and initiation of HAART was not possible. It is possible that STDs are more likely to be discovered in subjects with regular CM due to frequent surveillance. In addition, symptomatic patients seek medical consultation more often than asymptomatic subjects. Both factors would reduce the apparent protective effects of regular CM. However, among subjects with regular CM, cases with HAART still had the lower incidence of STDs, compared to cases without HAART. Thus, HAART is the important protective factor noted in this study.

Second, detection of STDs in this study was based on symptoms and laboratory diagnosis, which certainly underestimate STD incidence. Silent STDs may occur, especially among women with chlamydial infections.40 Differential diagnosis of primary and recurrent herpes simplex infection by using clinical symptoms, patients' information, and herpes IgM, which is occasionally produced in recurrent cases,41 is difficult. Moreover, IgG was not routinely analyzed in our patients. These factors resulted in the underestimation of primary herpes simplex infection. In addition, enrolled subjects may visit other clinics for STD treatments, lowering the estimated STD incidence. Nevertheless, the STD rate reported here is similar to that reported in previous studies,12,14,15,21,24,25,42,43 and represents the current scenario in Taiwan.

Finally, we tried several methods to analyze sexual risk behaviors and failed to identify an association with incident STDs. The adjusted HR for inconsistence of condom usage in the 3 months prior to disease or censoring was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.32–1.30; p=0.22). Similar results were obtained when we treated the sexual behavior as an increased percentage of condom usage after joining the CM program, or as an average rate of condom usage; in neither case did we detect a significant association. We considered that self-reports of sexual behavior in this study were biased, and the issue was not further discussed in this study; such evidence is known to be less reliable due to concerns of social desirability and privacy,44 especially in the conservative Chinese society. Modern technology such as audio computer-assisted self-interview or internet inquiry may deserve attention in this regard.

Although this retrospective study might underestimate the incidence of STDs and not draw the conclusion of causality, we noted that the CM program and HAART are associated with lower acquisition of incident STDs in the Taiwanese HIV-positive population. Thus, HIV-positive patients may benefit from the CM program and from the initiation of HAART.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants, and the Department of Health, Taiwan, for funding this study (Grant No. 10119).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control; Centers for Disease Control, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan. Statistics of communicable diseases and surveillance reports in Taiwan area. Dec, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov.tw/info.aspx? [Jun 17;2012 ]. http://www.cdc.gov.tw/info.aspx?

- 2.Palella FJ., Jr. Delaney KM. Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access, Progress Report 2011. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: [Jun 17;2012 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnell D. Baeten JM. Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: A prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montaner JS. Lima VD. Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: A population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:532–539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MS. Chen YQ. McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das M. Chu PL. Santos GM, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang CH HIV/AIDS data anlysis: A 5-year follow-up. DOH-98-DC-2027 [Centers for disease control]. Taipei, Taiwan. Centers for disease control. Dec 31, 2009. http://www2.cdc.gov.tw/public/data/022413521171.pdf. [Jun 17;2012 ]. http://www2.cdc.gov.tw/public/data/022413521171.pdf

- 9.Dougan S. Evans BG. Elford J. Sexually transmitted infections in Western Europe among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:783–790. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000260919.34598.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicoll A. Hughes G. Donnelly M, et al. Assessing the impact of national anti-HIV sexual health campaigns: Trends in the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in England. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:242–247. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcus U. Kollan C. Bremer V. Hamouda O. Relation between the HIV and the re-emerging syphilis epidemic among MSM in Germany: An analysis based on anonymous surveillance data. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:456–457. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.014555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieg G. Lewis RJ. Miller LG, et al. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: Prevalence, incidence, predictors, and screening strategies. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:947–954. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baffi CW. Aban I. Willig JH, et al. New syphilis cases and concurrent STI screening in a Southeastern U.S. HIV clinic: A call to action. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:23–29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganesan A. Fieberg A. Agan BK, et al. Results of a 25-year longitudinal analysis of the serologic incidence of syphilis in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with unrestricted access to care. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:440–448. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318249d90f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow EP. Wilson DP. Zhang L. HIV and syphilis co-infection increasing among men who have sex with men in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2012;6:e22768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyer JR. Eron JJ. Hoffman IF, et al. Association of CD4 cell depletion and elevated blood and seminal plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA concentrations with genital ulcer disease in HIV-1-infected men in Malawi. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:224–227. doi: 10.1086/517359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen MS. Hoffman IF. Royce RA, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: Implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1868–1873. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barth RE. Wensing AM. Tempelman HA, et al. Rapid accumulation of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-associated resistance: Evidence of transmitted resistance in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:2210–2212. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328313bf87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hue S. Gifford RJ. Dunn D, et al. Demonstration of sustained drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lineages circulating among treatment-naive individuals. J Virol. 2009;83:2645–2654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01556-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SC. Wang ST. Chen KT, et al. Analysis of the influence of therapy and viral suppression on high-risk sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infections among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:660–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko NY. Liu HY. Lee HC, et al. One-year follow-up of relapse to risky behaviors and incidence of syphilis among patients enrolled in the HIV case management program. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1067–1074. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson WD. Diaz RM. Flanders WD, et al. Behavioral interventions to reduce risk for sexual transmission of HIV among men who have sex with men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD001230. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001230.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao Z. Li X. Mehrotra P. HIV/sexual risk reduction interventions in China: A meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:597–613. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan S. Lu H. Ma X, et al. Behavioral and serologic survey of men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: Implication for HIV intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:148–155. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao M. Kang D. Jiang B, et al. Bisexual behavior and infection with HIV and syphilis among men who have sex with men along the east coast of China. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:683–691. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attia S. Egger M. Muller M. Zwahlen M. Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1397–1404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant RM. Lama JR. Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New Eng J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baeten JM. Donnell D. Ndase P. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New Eng J Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khawcharoenporn T. Kendrick S. Smith K. HIV risk perception and preexposure prophylaxis interest among a heterosexual population visiting a sexually transmitted infection clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:222–233. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heijman T. Geskus RB. Davidovich U, et al. Less decrease in risk behaviour from pre-HIV to post-HIV seroconversion among MSM in the combination antiretroviral therapy era compared with the pre-combination antiretroviral therapy era. AIDS. 2012;26:489–495. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f9d7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George N. Green J. Murphy S. Sexually transmitted disease rates before and after HIV testing. Int J STD AIDS. 1998;9:291–293. doi: 10.1258/0956462981922223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGowan JP. Shah SS. Ganea CE, et al. Risk behavior for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among HIV-seropositive individuals in an urban setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:122–127. doi: 10.1086/380128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marks G. Crepaz N. Senterfitt JW. Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diabate S. Alary M. Koffi CK. Short-term increase in unsafe sexual behaviour after initiation of HAART in Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2008;22:154–156. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f029e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hart GJ. Elford J. Sexual risk behaviour of men who have sex with men: Emerging patterns and new challenges. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:39–44. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328334feb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luchters S. Sarna A. Geibel S, et al. Safer sexual behaviors after 12 months of antiretroviral treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: A prospective cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:587–594. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peltzer K. Ramlagan S. Safer sexual behaviours after 1 year of antiretroviral treatment in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: A prospective cohort study. Sex Health. 2010;7:135–141. doi: 10.1071/SH09109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisele TP. Mathews C. Chopra M, et al. Changes in risk behavior among HIV-positive patients during their first year of antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1097–1105. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClelland RS. Graham SM. Richardson BA, et al. Treatment with antiretroviral therapy is not associated with increased sexual risk behavior in Kenyan female sex workers. AIDS. 2010;24:891–897. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833616c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamm WE. Batteiger BE. Chlamydia trachomatis (Trachoma, perinatal infections, lymphogranuloma venereum, and other genital infections) In: Mandell GL, editor; Bennet JE, editor; Dolin R, editor. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectisous Diseases. 7th. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2012. pp. 2443–2461. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Page J. Taylor J. Tideman RL, et al. Is HSV serology useful for the management of first episode genital herpes? Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:276–279. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erbelding EJ. Chung SE. Kamb ML, et al. New sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected patients: Markers for ongoing HIV transmission behavior. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:247–252. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Defraye A. Van Beckhoven D. Sasse A. Surveillance of sexually transmitted infections among persons living with HIV. Int J Public Health. 2011;56:169–174. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips AE. Gomez GB. Boily MC. Garnett GP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative interviewing tools to investigate self-reported HIV and STI associated behaviours in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1541–1555. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]