Abstract

PURPOSE

Realizing the benefits of adopting electronic health records (EHRs) in large measure depends heavily on clinicians and providers’ uptake and meaningful use of the technology. This study examines EHR adoption among family physicians using 2 different data sources, compares family physicians with other office-based medical specialists, assesses variation in EHR adoption among family physicians across states, and shows the possibility for data sharing among various medical boards and federal agencies in monitoring and guiding EHR adoption.

METHOD

We undertook a secondary analysis of American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) administrative data (2005–2011) and data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) (2001–2011).

RESULTS

The EHR adoption rate by family physicians reached 68% nationally in 2011. NAMCS family physician adoption rates and ABFM adoption rates (2005–2011) were similar. Family physicians are adopting EHRs at a higher rate than other office-based physicians as a group; however, significant state-level variation exists, indicating geographical gaps in EHR adoption.

CONCLUSION

Two independent data sets yielded convergent results, showing that adoption of EHRs by family physicians has doubled since 2005, exceeds other office-based physicians as a group, and is likely to surpass 80% by 2013. Adoption varies at a state level. Further monitoring of trends in EHR adoption and characterizing their capacities are important to achieve comprehensive data exchange necessary for better, affordable health care.

Keywords: electronic health record, family physicians, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, American Board of Family Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Electronic health records (EHRs) are generally expected to improve the quality of health care, lower health care costs, and provide patients with more involvement in their own health care.1,2 Federal efforts to increase adoption of EHRs have accelerated in recent years, especially with the 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, which created the Health Information Technology Regional Extension Centers (RECs). Sixty-two RECs were set up across the nation and awarded $657 million in federal funding in 2010.3 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also have set up incentives for adoption and meaningful use of EHRs and penalties for lack of provider engagement.4

The realization of EHR benefits depends heavily on health providers’ uptake of this technology. The Triple Aim initiative aspires to improve population health and health care delivery in the United States while controlling costs.5 The federal e-health directives outlined in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) support the Triple Aim and complement health delivery and payment reform initiatives specified in the Affordable Care Act.6 Realization of the Triple Aim will require data sharing and exchange that transects all aspects of health care delivery and depend in part on widespread adoption of EHRs, particularly by office-based physicians. Family physicians constitute an important case because they are the largest group of primary care physicians, and they distribute themselves more proportionately to the population than do other physician specialists, providing frontline health services at the community level.7

Considerable variation in EHR adoption has been documented. Simon et al reported 18% of office practices having an EHR in Massachusetts in 2005.8 Stream found a 58% adoption rate by family physicians in Washington State in 2007.9 Menachemi et al studied the increased use of EHRs by physicians in outpatient practices in Florida10,11 and found the overall EHR adoption rate in Florida rose from 23.7% in 2005 to 35.1% in 2008. Hsiao et al reported that the EHR adoption rate for office-based physicians reached 57% in 2011 nationally.12

In this study we used national data from 2 independent sources to estimate EHR uptake by family physicians and compared trends. We then compared adoption rates by family physicians with rates by other outpatient physicians and also investigated geographic variation in EHR adoption at the state level.

METHODS

For this study, we used data from a census survey completed by candidates applying for the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Maintenance of Certification examination and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Eighty-five percent of family physicians are certified by the ABFM.13 Beginning with the December 2005 Maintenance of Certification examination, the ABFM added a question regarding EHR adoption to its demographic questionnaire, specifically asking all candidates: “Do you use an electronic medical record system in your office?” The 2005 ABFM sample size was smaller than usual because the EHR question was first added for the 2005 winter examination. The 2010 and 2011 ABFM sample sizes were also smaller than usual because 76% of family physicians who certified or recertified in 2003 and 2004 successfully earned a full 10-year Maintenance of Certification cycle and will not return for recertification until 2013.14,15 No significant difference was observed in terms of age and sex, however, for 2005, 2010, and 2011 candidates in our samples compared with candidates in 2006 through 2009. Because candidates cannot proceed to examination otherwise, response rates are 100%.

The NAMCS, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), is an annual nationally representative survey of visits to office-based physicians and collects information on the adoption and use of EHRs. NAMCS estimates are weighted to account for nonresponse. Statistical testing involving NAMCS data took into account the complex sample design. For 2001 through 2011, we compared NAMCS reports of any EHR adoption among family physicians with that of all other office-based physicians.

We tested for differences between EHR adoption rates among family physicians in the NAMCS survey (NAMCS-FP) and ABFM rates for family physicians for 2005 through 2011, as well as for differences between ABFM and NAMCS adoption rates for family physicians (NAMCS-FP) and NAMCS adoption rates for physicians other than family physicians (NAMCS-NonFP) for 2001 through 2011. We compared these data using a 2 independent samples t test. Statistically significant differences were determined at P=.05 level. We then examined the most recent data available for variation in family physician EHR adoption rates across states using 2010–2011 ABFM data and 2010–2011 NAMCS data for office-based family physicians and other specialty office-based physicians. We used a 1-sample t test to compare state adoption rates by family physicians and physicians from other specialties with their respective national averages. State rates with a sample size of less than 15 or with a relative standard error of greater than 0.3 were considered unstable rates and thus omitted in state-specific comparisons. We then compared ABFM, NAMCS-FP, and NAMCS-NonFP rates for each state using the 2 independent samples t test.

RESULTS

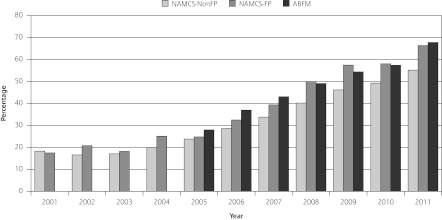

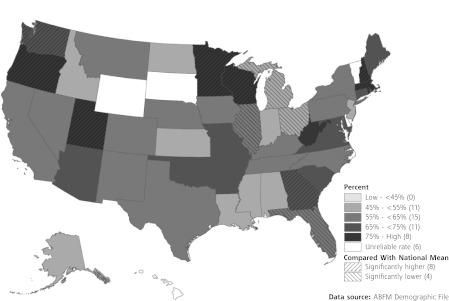

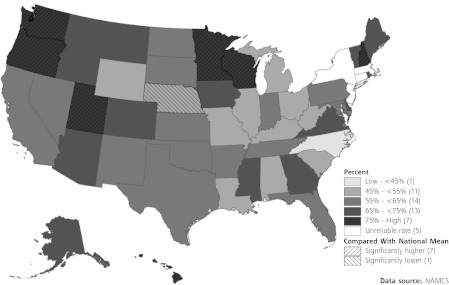

The EHR adoption rates based on both ABFM and NAMCS data rose steadily and doubled from 2005 to 2011 (Figure 1), reaching 67.8% for family physicians in 2011. NAMCS-FP and ABFM adoption rates were statistically similar between 2005 and 2011 (P >.05). Adoption rates for family physicians were significantly higher than for other office-based physicians (ABFM rate since 2006 and NAMCS-FP since 2008; Table 1). Significant variations in EHR adoption were observed across states. Rates reported by the ABFM ranged from a low of 47.1% in North Dakota to a high of 94.9% in Utah (Figure 2a). Georgia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin had significantly higher EHR adoption rates than the 2-year, pooled ABFM national average of 62.6%. On the other hand, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio had significantly lower EHR adoption rates than the ABFM national average. NAMCS-FP rates (Figure 2b) ranged from a low of 44% in North Carolina to a high of 87.6% in Hawaii. It also showed a strong regional clustering for adoption. Although most states had rates similar to those reported by NAMCS-FP and ABFM, significant differences were observed for North Carolina and South Carolina for adoption rates as estimated using ABFM and NAMCS-FP data (Supplemental Table 1, available at http://annfammed.org/content/11/1/14/suppl/ DC1). Significant state variations in EHR adoption among other office-based physicians were also apparent. States with higher EHR adoption among family physicians generally had higher EHR adoption for other office-based physicians, consistent with a state-level effect.

Figure 1.

The steady rise of EHR adoption by family physicians and other physician specialties, 2001–2011.

ABFM = American Board of Family Medicine; EHR = electronic health record; FP = family physician; NAMCS = National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

Data Source: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; American Board of Family Medicine Diplomate Database.

Table 1.

Comparison of Reported Adoption of EHRs by Family Physicians and Other Specialties, 2001–2011

| NAMCS-FP | NAMCS-NonFP | ABFM | NAMCS-FP vs NAMCS-NonFP P Value | NAMCS-FP vs ABFM P Value | NAMCS-NonFP vs ABFM P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | No. (%) | 95% CL | No. (%) | 95% CL | No. (%) | 95% CL | |||

| 2001 | 98 (17.5) | 10.5 - 27.9 | 915 (18.3) | 15.1-22.0 | – | – | .8511 | – | – |

| 2002 | 190 (20.8) | 15.0-28.0 | 1,043 (16.6) | 13.6-20.1 | – | – | .1619 | – | – |

| 2003 | 164 (18.2) | 12.3-26.1 | 950 (17.1) | 13.2-21.7 | – | – | .7165 | – | – |

| 2004 | 144 (25.1) | 17.8-34.3 | 977 (20.0) | 16.9-23.5 | – | – | .1548 | – | – |

| 2005 | 175 (24.8) | 17.8-33.5 | 1,106 (23.8) | 20.8-27.1 | 610 (28.0) | 24.5-31.6 | .7688 | .3979 | .0525 |

| 2006 | 19 6 ( 32.5) | 26.1-39.7 | 1,115 (28.6) | 25.0 -32.5 | 8, 263 (37.0) | 36.0 -38.0 | .2669 | .1979 | <.0001 |

| 2007 | 305 (39.4) | 33.1-46.0 | 1,438 (33.8) | 30.6-37.3 | 9,507 (43.1) | 42.1-44.0 | .0655 | .2012 | <.0001 |

| 2008 | 431 (50.0) | 42.5-57.4 | 1,907 (40.2) | 36.1-44.4 | 9,692 (49.1) | 48.1-50.1 | .0002 | .7359 | <.0001 |

| 2009 | 460 (57.5) | 52.3-62.5 | 2,186 (46.2) | 43.5-48.9 | 9,558 (54.4) | 53.4-55.4 | <.0001 | .1965 | <.0001 |

| 2010 | 925 (58.1) | 52.9-63.1 | 3,741 (49.3) | 46.8-51.8 | 2,437 (57.4) | 55.4-59.4 | <.0001 | .7334 | <.0001 |

| 2011 | 881 (66.4) | 61.3-71.0 | 3,445 (55.2) | 52.5-57.8 | 2,359 (67.8) | 65.9-69.7 | <.0001 | .5081 | <.0001 |

ABFM = American Board of Family Medicine; EHR = electronic health record; FP = family physician; NAMCS = National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; non-FP = all other physician specialties.

Figure 2a.

State variations in EHR adoption among family physicians (ABFM), 2010–2011.

ABFM = American Board of Family Medicine; EHR = electronic health record.

Note: Number in parentheses in the legend indicates the number of states in each category.

Figure 2b.

State variations in EHR adoption among family physicians (NAMCS-FP), 2010–2011.

EHR = electronic health record; FP = family physician; NAMCS = National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

Note: Number in parentheses in the legend indicates the number of states in each category.

DISCUSSION

EHR adoption by family physicians has steadily risen reaching approximately 67% in 2011. Both NAMCS and ABFM data indicated that the EHR adoption rate by family physicians has more than doubled from 2005 to 2011. We project that it could surpass an 80% threshold nationally by 2013 based on the current trend. Adoption by family physicians exceeds that of other office-based physicians as a group, conforming to what many have reported—that primary care physician adoption rate is higher than that of other specialists.8,16,17 The NAMCS EHR adoption rate by family physicians based on a random sample was not significantly different from the ABFM adoption rate based on recertifying family physicians, lending credibility to these estimates. Significant state variation in the adoption of EHRs existed for both family physicians and other office-based physicians, inviting further research and policy making.

NAMCS has included data on EHR adoption since 2001, modified in 2005 to elicit information on specific features of computerized systems. Since 2010, the sample size for the NAMCS supplemental mail survey increased fivefold to provide overall state-level estimates, but not by subpopulations, such as single physician specialty, because of small sample sizes in the subpopulations. ABFM’s EHR survey question has been consistent, with 100% response rates throughout our study period, but it lacks a predetermined operational definition of an EHR and data about specific features, precluding more granular comparisons. Hsaio et al reported a 34% national adoption rate for all physicians having a system that met the criteria for a basic EHR system in 2011,12 suggesting caution in assumptions about the capacities of adopted EHRs.

The multispecialty NAMCS survey allows examination of differential adoption trends among different medical specialties, and the large sample sizes within the ABFM data set allow adoption rate estimation at smaller geographic units. Our study exemplifies how a federally funded data set and medical board data set with different capacities can be used together to extend analyses relevant to important contemporary issues.

What explains the significant variation in family physician EHR adoption rates among states is unknown. It is possible that initiatives may not exist to help physicians adopt EHRs in low-adoption states. Angst and colleagues identified 4 consistent themes with regard to embracing health information technology (HIT) among states.18 One of these themes was “innovative HIT funding mechanisms,” which offer financial support for HIT adoption, such as EHR implementation, prescription drug tracking, and quality data reporting. They found substantial variation in states’ commitment to these issues. Variation in the penetration of health maintenance organizations or other integrated health systems among states may also explain some of the variation. Large practices and organizations may be more prevalent in some states and able to more easily adopt EHRs. Whatever the explanation, the interstate variability could help identify areas for targeted interventions, eg, adjustments to federal funding for various RECs.

Two independent data sets yielded convergent results, showing that adoption of EHRs by family physicians has doubled since 2005, exceeds other office-based physicians as a group, and is likely to surpass 80% by 2013. Adoption varies at a state level. Further monitoring of trends in EHR adoption and characterizing their capacities are important to achieve comprehensive data exchange necessary for health care. Now that EHRs are common, important research is both increasingly plausible and essential to determine how EHRs can improve health care and population health and help contain costs.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/11/1/14.

Additional information: This article was submitted for publication while Dr Xierali was at the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Disclaimer: The information and opinions contained in research from the Graham Center do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Acknowledgments:

This paper has been reviewed and cleared for publication through the review process of the National Center for Health Statistics. We would like to thank Drs Jennifer Madans and Sandra Decker for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

References

- 1.Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1477–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5): 382–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Health Information Technology Extension Program. Listing of regional extension centers http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/community/healthit_hhs_gov__listing_of_regional_extension_centers/3519 Accessed Feb 8, 2012

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services The official web site for the Medicare and Medicaid electronic health record (EHR) incentive programs. http://www.cms.gov/EHRIncentivePrograms/ Accessed May 26, 2011

- 5.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Excellence (Excerpts). Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Office of E-Health Standards & Services; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazemore AW, Burke M, Xierali IM, et al. Establishing a baseline: health information technology adoption among family medicine diplomates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(2):132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon SR, McCarthy ML, Kaushal R, et al. Electronic health records: which practices have them, and how are clinicians using them? J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stream GR. Trends in adoption of electronic health records by familyphysicians in Washington State. Inform Prim Care. 2009;17(3):145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menachemi N, Perkins RM, van Durme DJ, Brooks RG. Examining the adoption of electronic health records and personal digital assistants by family physicians in Florida. Inform Prim Care. 2006;14(1):1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menachemi N, Powers TL, Brooks RG. Physician and practice characteristics associated with longitudinal increases in electronic health records adoption. J Healthc Manag. 2011;56(3):183–197, discussion 197–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsiao CJ, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B. Electronic Health Record Systems and Intent to Apply for Meaningful Use Incentives Among Office-Based Physician Practices: United States, 2001–2011. NCHS data brief, no 79. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xierali IM, Rinaldo JCB, Green LA, et al. Family physician participation in maintenance of certification. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(3):203–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puffer JC, Bazemore AW, Newton WP, Makaroff L, Xierali IM, Green LA. Engagement of family physicians seven years into maintenance of certification. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):483–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puffer JC, Bazemore AW, Jaén CR, Xierali IM, Phillips RL, Jones SM. Engagement of family physicians in maintenance of certification remains high. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(6):761–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):50–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decker SL, Jamoom EW, Sisk JE. (2012). Physicians in nonprimary care and small practices and those age 55 and older lag in adopting electronic health record systems. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):1108–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angst CM, Desai A, Wulff J. State-Level HIT Activity and Themes. CHIDS Research Briefings (1:2B), Center for Health Information and Decision Systems, Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland; 2006:1–4 [Google Scholar]