Abstract

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation reactions are efficient and direct routes to prepare complex and stereodefined organomagnesium and organozinc reagents. However, carbon–carbon unsaturated bonds are generally unreactive toward organomagnesium and organozinc reagents. Thus, transition metals were employed to accomplish the carbometalation involving wide varieties of substrates and reagents. Recent advances of transition-metal-catalyzed carbomagnesiation and carbozincation reactions are reviewed in this article. The contents are separated into five sections: carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of (1) alkynes bearing an electron-withdrawing group; (2) alkynes bearing a directing group; (3) strained cyclopropenes; (4) unactivated alkynes or alkenes; and (5) substrates that have two carbon–carbon unsaturated bonds (allenes, dienes, enynes, or diynes).

Keywords: alkene, alkyne, carbomagnesiation, carbometalation, carbozincation, transition metal

Introduction

Whereas direct transformations of unreactive carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bonds have been attracting increasing attention from organic chemists, classical organometallic reagents still play indispensable roles in modern organic chemistry. Among the organometallic reagents, organomagnesium and organozinc reagents have been widely employed for organic synthesis due to their versatile reactivity and availability. The most popular method for preparing organomagnesium and organozinc reagents still has to be the classical Grignard method [1], starting from magnesium or zinc metal and organic halides [2–7]. Although the direct insertion route is efficient and versatile, stereocontrolled synthesis of organomagnesium or organozinc reagents, especially of alkenyl or alkyl derivatives, is always difficult since the metal insertion process inevitably passes through radical intermediates to lose stereochemical information [5,8]. Halogen–metal exchange is a solution for the stereoselective synthesis [9–13]. However, preparation of the corresponding precursors can be laborious when highly functionalized organometallic species are needed. Thus, many organic chemists have focused on carbometalation reactions that directly transform simple alkynes and alkenes to structurally complex organometallics with high stereoselectivity.

In general, carbon–carbon multiple bonds are unreactive with organomagnesium and organozinc reagents. Hence, limited substrates and reagents could be employed for uncatalyzed intermolecular carbometalation. Naturally, many groups envisioned transition-metal-catalyzed carbometalation reactions that directly convert alkynes and alkenes to new organomagnesium and organozinc reagents [14–33]. The resulting organomagnesium and organozinc intermediates have versatile reactivity toward various electrophiles to provide multisubstituted alkenes and alkanes. Thus, carbomagnesiation and carbozincation reactions are highly important in organic synthesis. Although intramolecular carbomagnesiation and -zincation [15] and intermolecular carbocupration with stoichiometric copper reagents has been well established [14,18,25], catalytic intermolecular carbomagnesiation and carbozincation are still in their infancy.

This article includes the advances in transition-metal-catalyzed intermolecular carbomagnesiation and carbozincation reactions that have been made in the past 15 years, promoting the development of these potentially useful technologies. The contents are categorized by the substrates (Scheme 1): (1) alkynes bearing an electron-withdrawing group; (2) alkynes bearing a directing group; (3) cyclopropenes; (4) unactivated alkynes or alkenes; and (5) substrates that have two carbon–carbon unsaturated bonds (allenes, dienes, enynes, or diynes).

Scheme 1.

Variation of substrates for carbomagnesiation and carbozincation in this article.

Review

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of electron-deficient alkynes

Since conjugate addition reactions of organocuprates with alkynyl ketones or esters have been well established [14,34–37], alkynes bearing an electron-withdrawing group other than carbonyl have been investigated recently [25,38]. The Xie, Marek, and Tanaka groups have been interested in copper-catalyzed carbometalation of sulfur-atom-substituted alkynes, such as alkynyl sulfones, sulfoxides, or sulfoximines as electron-deficient alkynes. Xie reported a copper-catalyzed carbomagnesiation of alkynyl sulfone to give the corresponding alkenylmagnesium intermediates (Scheme 2) [39–40]. Interestingly, the stereochemistry of the products was nicely controlled by the organomagnesium reagents and electrophiles employed. The reaction with arylmagnesium reagents provided alkenylmagnesium intermediate 1a. The reaction of 1a with allyl bromide provided syn-addition product 1b in 70% yield while the reaction with benzaldehyde afforded anti-addition product 1c in 59% yield. In contrast, allylmagnesiated intermediate 1d reacted with benzaldehyde to give syn-addition product 1e stereoselectively.

Scheme 2.

Copper-catalyzed arylmagnesiation and allylmagnesiation of alkynyl sulfone.

Marek reported copper-catalyzed carbometalation of alkynyl sulfoximines and sulfones using organozinc reagents of mild reactivity [41]. Various organozinc reagents can be used, irrespective of the identity of the organic groups, preparative protocols, and accompanying functional groups (Table 1). Similarly, Xie reported ethyl- or methylzincation of alkynyl sulfones [42] and Tanaka reported carbozincation of alkynyl sulfoxides [43–44].

Table 1.

Copper-catalyzed carbozincation of alkynyl sulfoximines.

| ||

| Entry | RZnX | Yield |

| 1 | Et2Zn | 82% |

| 2 | EtZnIa | 90% |

| 3 | OctZnIb | 55% |

| 4 | EtZnBrc | 75% |

| 5 | iPrZnBrc | 80% |

| 6 | PhZnBrc | 85% |

| 7 | MeOCO(CH2)3ZnIb | 55% |

| 8 |  |

72% |

aPrepared from Et2Zn and I2. bPrepared from the corresponding alkyl iodide and zinc dust. cGenerated from the corresponding Grignard reagent and ZnBr2. dPrepared from the corresponding vinyl iodide by iodine–lithium exchange and followed by transmetalation with ZnBr2.

Marek discovered efficient methods for the stereoselective synthesis of multisubstituted allylic zinc intermediates 1f from alkynyl sulfoxides with organomagnesium or -zinc reagents (Scheme 3) [45–46]. It is noteworthy that they applied their chemistry to the preparation of various allylic metals [24–25,47–53] or enolates [54] from simple alkynes by carbocupration reactions.

Scheme 3.

Copper-catalyzed four-component reaction of alkynyl sulfoxide with alkylzinc reagent, diiodomethane, and benzaldehyde.

Not only copper but also rhodium can catalyze carbometalation reactions. Hayashi applied carborhodation chemistry [55–58] to the reactions of aryl alkynyl ketones with arylzinc reagents, which provided enolates of indanones (Scheme 4) [59]. Phenylrhodation of 1g first proceeds to form 1A. A subsequent intramolecular 1,4-hydrogen shift gives 1B, which smoothly undergoes an intramolecular 1,4-addition to yield 1C. Finally, transmetalation from the phenylzinc reagent to rhodium enolate 1C affords zinc enolate 1h, which reacts with allyl bromide to give 1i in 60% yield.

Scheme 4.

Rhodium-catalyzed reaction of aryl alkynyl ketones with arylzinc reagents.

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of alkynes bearing a directing group

Directing groups have been utilized in successful carbometalation with high regio- and stereoselectivity. Classically, hydroxy groups on propargylic alcohols are used in uncatalyzed carbomagnesiation (Scheme 5) [60–61]. This addition proceeded in an anti fashion to give intermediate 2a. The trend is the same in copper-catalyzed reactions of wide scope [62]. In 2001, Negishi applied copper-catalyzed allylmagnesiation to the total synthesis of (Z)-γ-bisabolene (Scheme 6) [63].

Scheme 5.

Allylmagnesiation of propargyl alcohol, which provides the anti-addition product.

Scheme 6.

Negishi’s total synthesis of (Z)-γ-bisabolene by allylmagnesiation.

Recently, Ready reported an intriguing iron-catalyzed carbomagnesiation of propargylic and homopropargylic alcohols 2b to yield syn-addition intermediates 2c with opposite regioselectivity (Scheme 7) [64]. They assumed that the key organo-iron intermediate 2A underwent oxygen-directed carbometalation to afford 2B or 2C (Scheme 8). Further transmetalation of vinyliron intermediate 2B or 2C with R′MgBr yielded the corresponding vinylmagnesium intermediate 2D. Therefore, selective synthesis of both regioisomers of allylic alcohols can be accomplished by simply choosing transition-metal catalysts (Cu or Fe). Methyl-, ethyl-, and phenylmagnesium reagents could be employed for the reaction.

Scheme 7.

Iron-catalyzed syn-carbomagnesiation of propargylic or homopropargylic alcohol.

Scheme 8.

Mechanism of iron-catalyzed carbomagnesiation.

Aside from the examples shown in Scheme 5 and Scheme 6, alkynes that possess a directing group usually undergo syn-addition. Oshima reported manganese-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective carbomagnesiation of homopropargyl ether 2d leading to the formation of the corresponding syn-addition product 2e (Scheme 9) [65]. The reaction of [2-(1-propynyl)phenyl]methanol (2f) also proceeded in a syn fashion (Scheme 10) [66–68].

Scheme 9.

Regio- and stereoselective manganese-catalyzed allylmagnesiation.

Scheme 10.

Vinylation and alkylation of arylacetylene-bearing hydroxy group.

In 2003, Itami and Yoshida revealed a concise synthesis of tetrasubstituted olefins from (2-pyridyl)silyl-substituted alkynes. The key intermediate 2h was prepared by copper-catalyzed arylmagnesiation of 2g, in which the 2-pyridyl group on silicon efficiently worked as a strong directing group (Scheme 11) [69]. Furthermore, they accomplished a short and efficient synthesis of tamoxifen from 2g (Scheme 12). Notably, the synthetic procedure is significantly versatile and various tamoxifen derivatives were also prepared in just three steps from 2g.

Scheme 11.

Arylmagnesiation of (2-pyridyl)silyl-substituted alkynes.

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of tamoxifen from 2g.

The directing effect dramatically changed the regioselectivity in the reactions of oxygen- or nitrogen-substituted alkynes. Carbocupration of these alkynes generally gives the vicinal product 2D (copper locates at the β-position to the O or N) (Scheme 13, path A) [14,70–73]. On the other hand, the reversed regioselectivity was observed in the carbocupration of O-alkynyl carbamate and N-alkynyl carbamate, in which carbonyl groups worked as a directing group to control the regioselectivity to afford 2E (Scheme 13, path B) [25,74–76].

Scheme 13.

Controlling regioselectivity of carbocupration by attaching directing groups.

In 2009, Lam reported the rhodium-catalyzed carbozincation of ynamides. The reaction smoothly proceeded under mild conditions to provide the corresponding intermediate 2i regioselectively (Scheme 14) [77–78]. A wide variety of ynamides and organozinc reagents could be used for the reaction (Table 2).

Scheme 14.

Rhodium-catalyzed carbozincation of ynamides.

Table 2.

Scope of rhodium-catalyzed carbozincation of ynamide.

| |||||

| Reagent | Product | Yield [%] | Reagent | Product | Yield [%] |

| Bn2Zn |  |

71 | (p-FC6H4)2Zn |  |

84 |

| (vinyl)2Zn |  |

66 | (phenylethynyl)2Zn |  |

60 |

| (2-propenyl)2Zn |  |

47 | EtO2C(CH2)3ZnBr |  |

54 |

| (2-thienyl)2Zn |  |

66 | m-EtO2CC6H4ZnI |  |

58 |

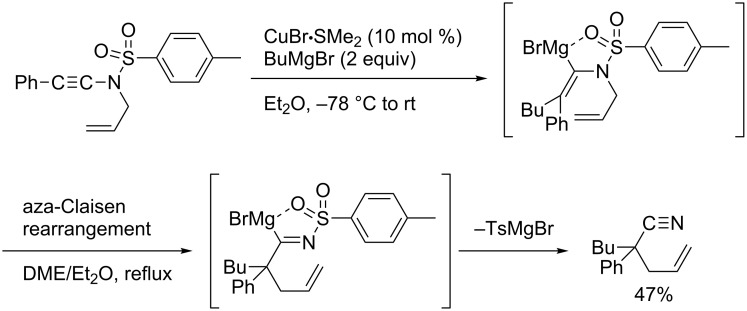

Yorimitsu and Oshima reported an interesting transformation of ynamides to nitriles by a carbomagnesiation/aza-Claisen rearrangement sequence (Scheme 15) [79–80].

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of 4-pentenenitriles through carbometalation followed by aza-Claisen rearrangement.

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of cyclopropenes

Increasing the reactivity of alkynes and alkenes is another strategy to achieve intermolecular carbometalation reactions. For example, strained alkenes are highly reactive toward carbometalation. The reactions of cyclopropenes took place without the aid of a metal catalyst (Scheme 16) [81].

Scheme 16.

Uncatalyzed carbomagnesiation of cyclopropenes.

Nakamura and co-workers discovered that an addition of iron salt enhanced the carbometalation of cyclopropenone acetal with organomagnesium and -zinc species (Scheme 17) and applied the reaction to enantioselective carbozincation (Scheme 18) [82–83]. The scope was wide enough to use phenyl-, vinyl-, and methylmagnesium reagents or diethylzinc and dipentylzinc reagents. It is noteworthy that the reaction in the absence of the iron catalyst did not proceed at low temperature and gave a complex mixture at higher temperature (up to 65 °C).

Scheme 17.

Iron-catalyzed carbometalation of cyclopropenes.

Scheme 18.

Enantioselective carbozincation of cyclopropenes.

A hydroxymethyl group also showed a significant directing effect in the copper-catalyzed reaction of cyclopropene 3a with methylmagnesium reagent to afford 3b with perfect stereoselectivity (Scheme 19) [84]. Not only methylmagnesium reagents but also vinyl- or alkynylmagnesium reagents could be employed. Although the arylation reaction did not proceed under the same conditions (Scheme 20, top), the addition of tributylphosphine and the use of THF as a solvent enabled the stereoselective arylmagnesiation with high efficiency (Scheme 20, bottom) [85]. Similarly, carbocupration reactions of 1-cyclopropenylmethanol and its derivatives using the directing effect of the hydroxymethyl group are also known [86–89].

Scheme 19.

Copper-catalyzed facially selective carbomagnesiation.

Scheme 20.

Arylmagnesiation of cyclopropenes.

Notably, Fox reported the enantio- and stereoselective carbomagnesiation of cyclopropenes without the addition of transition metals (Scheme 21) [90]. The key to successful reactions is the addition of aminoalcohol 3c and 1 equiv of methanol. In 2009, Fox et al. improved their copper-catalyzed carbometalation reactions of cyclopropenes by using functional-group-tolerable organozinc reagents (Scheme 22) such as dimethyl-, diethyl-, diphenyl-, diisopropyl-, and divinylzinc reagents [91]. Treatment of cyclopropene 3d with dimethylzinc in the presence of a catalytic amount of copper iodide afforded organozinc intermediate 3e and finally 3f after protonolysis. In 2012, Fox reported the stereoselective copper-catalyzed arylzincation of cyclopropenes with a wider variety of arylzinc reagents [92]. The organozinc reagents were prepared by iodine/magnesium exchange and the subsequent transmetalation to zinc, and then used directly in one pot (Table 3).

Scheme 21.

Enantioselective methylmagnesiation of cyclopropenes without catalyst.

Scheme 22.

Copper-catalyzed carbozincation.

Table 3.

Sequential I/Mg/Zn exchange and arylzincation of cyclopropenes.

| |||||

| Reaction step 1. | Product | Yield [%] (dr) |

Reaction step 1. | Product | Yield [%] (dr) |

| iPrMgCl, Et2O, rt |

|

81 (>95:5) |

PhMgBr, THF, −35 °C |

|

62 (95:5) |

| iPrMgCl, THF, −35 °C |

|

69 (>95:5) |

PhMgBr, THF, −40 °C |

|

61 (>95:5) |

| iPrMgCl, Et2O, −35 °C |

|

70 (>95:5) |

iPrMgBr, THF, rt |

|

60 (88:12) |

| iPrMgCl, THF, −35 °C |

|

55 (91:9) |

|||

Lautens reported enantioselective carbozincation of alkenes using a palladium catalyst with a chiral ligand (Scheme 23) [93]. Treatment of 3g with diethylzinc in the presence of catalytic amounts of palladium salt, (R)-tol-BINAP, and zinc triflate and subsequent quenching with benzoyl chloride afforded 3h in 75% yield with 93% ee. The addition of zinc triflate may help the formation of a more reactive cationic palladium(II) species. Under similar conditions, Lautens also reported palladium-catalyzed carbozincation of oxabicycloalkenes [94].

Scheme 23.

Enantioselective ethylzincation of cyclopropenes.

Terao and Kambe reported two types of intriguing ring-opening carbomagnesiations of a methylenecyclopropane that proceed through site-selective carbon–carbon bond cleavage (Scheme 24) [95]. The reaction pathways depended on the reagents used, i.e., the reaction with a phenylmagnesium reagent provided 3i whereas the reaction with a vinylmagnesium reagent gave 3j. The reaction mechanisms are shown in Scheme 25. They proposed that the carbon–carbon bond cleavage happened prior to the carbometalation reactions, which is different from other ring-opening reactions of cyclopropenes [96–97] where carbometalation is followed by carbon–carbon bond cleavage. Firstly, the oxidative addition of methylenecyclopropane to the reduced nickel(0) may yield 3A or 3C. The subsequent isomerization would proceed to form 3B or 3D, respectively, and then reductive elimination would afford the corresponding organomagnesium intermediate 3i or 3j.

Scheme 24.

Nickel-catalyzed ring-opening aryl- and alkenylmagnesiation of a methylenecyclopropane.

Scheme 25.

Reaction mechanism.

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of unfunctionalized alkynes and alkenes

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of simple alkynes has been a longstanding challenge. In 1978, Duboudin reported nickel-catalyzed carbomagnesiation of unfunctionalized alkynes, such as phenylacetylenes and dialkylacetylenes (Scheme 26) [98]. Although this achievement is significant as an intermolecular carbomagnesiation of unreactive alkynes, the scope was fairly limited and yields were low.

Scheme 26.

Nickel-catalyzed carbomagnesiation of arylacetylene and dialkylacetylene.

In 1997, Knochel reported nickel-catalyzed carbozincation of arylacetylenes (Scheme 27) [99–100]. The reaction smoothly proceeded at –35 °C and exclusively produced tetrasubstituted (Z)-alkene 4a in high yield. Not only diphenylzinc reagent but also dimethyl- and diethylzinc reagents were employed. Chemists at the Bristol-Myers Squibb company developed a scalable synthesis of (Z)-1-bromo-2-ethylstilbene (4b), a key intermediate of a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, using the modified Knochel’s carbozincation method (Scheme 28) [101]. It is noteworthy that the modified nickel-catalyzed reaction could be performed at 20 °C to afford 57 kg of the corresponding phenylated product (58% yield) from 44 kg of 1-phenyl-1-butyne.

Scheme 27.

Nickel-catalyzed carbozincation of arylacetylenes and its application to the synthesis of tamoxifen.

Scheme 28.

Bristol-Myers Squibb’s nickel-catalyzed phenylzincation.

Oshima reported manganese-catalyzed phenylmagnesiation of a wide range of arylacetylenes (Table 4) [102]. Notably, directing groups, such as ortho-methoxy or ortho-amino groups, facilitated the reaction (Table 4, entries 2 and 3 versus entry 4).

Table 4.

Manganese-catalyzed arylmagnesiation of arylacetylenes.

| ||

| Entry | Ar | Yield |

| 1 | Ph | 66% |

| 2 | o-Me2NC6H4 | 94% |

| 3 | o-MeOC6H4 | 80% |

| 4 | p-MeOC6H4 | 38% |

| 5 | o-FC6H4 | 47% |

Recently, iron and cobalt have been regarded as efficient catalysts for carbometalation of simple alkynes. Shirakawa and Hayashi reported that iron salts could catalyze arylmagnesiation of arylacetylenes in the presence of an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand (Scheme 29) [103].

Scheme 29.

Iron/NHC-catalyzed arylmagnesiation of aryl(alkyl)acetylene.

In 2012, Shirakawa and Hayashi reported iron/copper cocatalyzed alkene–Grignard exchange reactions and their application to one-pot alkylmagnesiation of alkynes (Scheme 30) [104]. The exchange reactions proceeded through a β-hydrogen elimination–hydromagnesiation sequence to generate 4c. The alkylmagnesiation reactions of 1-phenyl-1-octyne with 4c provided the corresponding alkylated products 4d exclusively without contamination by the hydromagnesiated products of alkynes. In contrast, Nakamura reported the iron-catalyzed hydromagnesiation of diarylacetylenes and diynes with ethylmagnesium bromide as a hydride donor without forming alkylated products (Scheme 31) [105].

Scheme 30.

Iron/copper-cocatalyzed alkylmagnesiation of aryl(alkyl)acetylenes.

Scheme 31.

Iron-catalyzed hydrometalation.

As shown in Scheme 32, carbomagnesiation of dialkylacetylene provided the corresponding arylated product only in low yield. Although Negishi reported ethylzincation [106], allylzincation [107], and methylalumination [108] with a stoichiometric amount of zirconium salt, the examples of transition-metal-catalyzed carbometalation of dialkylacetylenes were limited only to carboboration [109–110] and carbostannylation [111]. In 2005, Shirakawa and Hayashi reported iron/copper-cocatalyzed arylmagnesiation of dialkylacetylenes [112]. This is the first successful catalytic carbomagnesiation of dialkylacetylenes. Note that Ilies and Nakamura reported iron-catalyzed annulation reactions of various alkynes, including dialkylacetylenes with 2-biphenylylmagnesium reagents to form phenanthrene structures [113].

Scheme 32.

Iron/copper-cocatalyzed arylmagnesiation of dialkylacetylenes.

In 2007, Yorimitsu and Oshima reported that chromium chloride could catalyze the arylmagnesiation of simple alkynes [114]. They found that the addition of a catalytic amount of pivalic acid dramatically accelerated the reaction (Table 5). Although the reason for the dramatic acceleration is not clear, the reaction provided various tetrasubstituted alkenes efficiently with good stereoselectivity (Scheme 33).

Table 5.

Acceleration effect of additive on chromium-catalyzed arylmagnesiation.

| |||

| Entry | Additive | Time | Yield (E/Z) |

| 1 | None | 18 h | 81% (91:9) |

| 2 | MeOH | 2 h | 77% (95:5) |

| 3 | MeCO2H | 0.25 h | 79% (>99:1) |

| 4 | PhCO2H | 0.25 h | 81% (>99:1) |

| 5 | t-BuCO2H | 0.25 h | 87% (>99:1) |

Scheme 33.

Chromium-catalyzed arylmagnesiation of alkynes.

A more versatile arylmetalation of dialkylacetylenes using arylzinc reagents in the presence of a cobalt catalyst was then reported by Yorimitsu and Oshima (Scheme 34, top) [115]. Treatment of dialkylacetylenes with arylzinc reagents in acetonitrile in the presence of a catalytic amount of cobalt bromide afforded the corresponding arylated intermediate 4e. Further study by Yoshikai revealed that the use of Xantphos as a ligand totally changed the products [116]. Smooth 1,4-hydride migration from 4A to 4B happened to provide organozinc 4f (Scheme 34, bottom). The versatile 1,4-migration reactions were widely applicable for the 1,2-difunctionalization of arenes.

Scheme 34.

Cobalt-catalyzed arylzincation of alkynes.

In 2012, Gosmini reported similar cobalt-catalyzed arylzincation reactions of alkynes, which provided tri- or tetrasubstituted alkenes with high stereoselectivity [117]. Their catalytic system was dually efficient: the simple CoBr2(bpy) complex worked as a catalyst not only for arylzincation but also for the formation of arylzinc reagents (Scheme 35).

Scheme 35.

Cobalt-catalyzed formation of arylzinc reagents and subsequent arylzincation of alkynes.

Yorimitsu and Oshima also accomplished benzylzincation of simple alkynes to provide allylbenzene derivatives in high yields (Scheme 36) [118]. For the reactions of simple dialkylacetylenes, benzylzinc bromide was effective (Scheme 36, top). On the other hand, dibenzylzinc reagent was effective for the reactions of aryl(alkyl)acetylenes (Scheme 36, bottom). They applied the reaction toward the synthesis of an estrogen-receptor antagonist (Scheme 37). Although the cobalt-catalyzed allylzincation reactions of dialkylacetylenes resulted in low yield, the reactions of arylacetylenes provided various tri- or tetrasubstituted styrene derivatives (Scheme 38) [119–120].

Scheme 36.

Cobalt-catalyzed benzylzincation of dialkylacetylene and aryl(alkyl)acetylenes.

Scheme 37.

Synthesis of estrogen receptor antagonist.

Scheme 38.

Cobalt-catalyzed allylzincation of aryl-substituted alkynes.

Kambe reported a rare example of silver catalysis for carbomagnesiation reactions of simple terminal alkynes (Scheme 39) [121–122]. They proposed that the catalytic cycle (Scheme 40) would be triggered by the transmetalation of AgOTs with iBuMgCl to afford isobutylsilver complex 4C. Complex 4C would react with tert-butyl iodide to generate tert-butylsilver intermediate 4D. Carbometalation of terminal alkynes with 4D, probably by addition of a t-Bu radical, would yield vinylsilver 4E. Finally, transmetalation with iBuMgCl would give the corresponding vinylmagnesium intermediate 4g. Due to the intermediacy of radical intermediates, the carbomagnesiation is not stereoselective.

Scheme 39.

Silver-catalyzed alkylmagnesiation of terminal alkyne.

Scheme 40.

Proposed mechanism of silver-catalyzed alkylmagnesiation.

In 2000, Negishi reported zirconium-catalyzed ethylzincation of 1-decene to provide dialkylzinc intermediate 4h (Scheme 41) [123]. Intermediate 4h reacted with iodine to provide alkyl iodide 4i in 90% yield. The carbozincation reaction is cleaner and affords the corresponding products in high yields compared with the reported carbomagnesiation reactions [124–129].

Scheme 41.

Zirconium-catalyzed ethylzincation of terminal alkenes.

Hoveyda reported zirconium-catalyzed alkylmagnesiation reactions of styrene in 2001 by using primary or secondary alkyl tosylates as alkyl sources [130]. The reactions proceeded through zirconacyclopropane 4F as a key intermediate to provide the corresponding alkylmagnesium compounds 4j, which could be employed for further reactions with various electrophiles (Scheme 42).

Scheme 42.

Zirconium-catalyzed alkylmagnesiation.

In 2004, Kambe reported titanocene-catalyzed carbomagnesiation, which proceeded through radical intermediates not metallacyclopropanes (Scheme 43) [131]. As a result, Hoveyda’s zirconium-catalyzed reactions provided homobenzylmagnesium intermediates 4j, while Kambe’s titanium-catalyzed reactions afforded benzylmagnesium intermediates 4k. Kambe applied the titanocene-catalyzed reaction to a three-component coupling reaction involving a radical cyclization reaction (Scheme 44).

Scheme 43.

Titanium-catalyzed carbomagnesiation.

Scheme 44.

Three-component coupling reaction.

Under Nakamura’s iron-catalyzed carbometalation reaction conditions (shown in Scheme 17), the reaction of oxabicyclic alkenes provided ring-opened product 4m through a carbomagnesiation/elimination pathway (Scheme 45, reaction 4l to 4m) [82]. In contrast, the use of the 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)benzene (dppbz) ligand efficiently suppressed the elimination pathway to provide the corresponding carbozincation product 4o in high yield (Scheme 45, reaction 4n to 4o) [132].

Scheme 45.

Iron-catalyzed arylzincation reaction of oxabicyclic alkenes.

Carbomagnesiation and carbozincation of allenes, dienes, enynes, and diynes

Interesting transformations were accomplished by the carbometalation of allenes, dienes, enynes, and diynes, since the resulting organometallic species inherently have additional saturation for further elaboration.

In 2002, Marek reported the reaction of allenyl ketones 5a with organomagnesium reagents in the absence of a catalyst [133]. The reaction yielded α,β-unsaturated ketone (E)-5b as a single isomer in ether solution, while a mixture of isomers 5b and 5d was obtained in THF solution (Scheme 46). They proposed that the reason for the selectivity would be attributed to intermediate 5c, which could stably exist in the less coordinative ether solution.

Scheme 46.

Reaction of allenyl ketones with organomagnesium reagent.

Using an iron catalyst dramatically changed the trend of the addition product. Ma reported that treatment of a 2,3-allenoate with methylmagnesium reagent in the presence of a catalytic amount of iron catalyst exclusively gave the corresponding product 5e (Scheme 47) [134]. Not only primary alkylmagnesium reagents but also secondary alkyl-, phenyl-, and vinylmagnesium reagents could be employed. Notably, α,β-unsaturated ester 5f was not formed and the reaction was highly Z-selective. Ma explained that transition state 5A would be favored because of the sterics to form intermediate 5g. Independently, Kanai and Shibasaki reported copper-catalyzed enantioselective alkylative aldol reactions starting from 1,2-allenoate and dialkylzinc [135], which may proceed through carbometalation intermediates 5B (Scheme 48).

Scheme 47.

Regio- and stereoselective reaction of a 2,3-allenoate.

Scheme 48.

Three-component coupling reaction of 1,2-allenoate, organozinc reagent, and ketone.

Yorimitsu and Oshima reported a rhodium-catalyzed arylzincation of simple terminal allenes that provided allylic zinc intermediates 5h (Scheme 49) [136]. The resulting allylic zinc intermediates 5h reacted with various electrophiles with high regio- and stereoselectivity. Thus, the reactions were applied to the synthesis of stereodefined skipped polyene 5i via iterative arylzincation/allenylation reactions (Scheme 50).

Scheme 49.

Proposed mechanism for a rhodium-catalyzed arylzincation of allenes.

Scheme 50.

Synthesis of skipped polyenes by iterative arylzincation/allenylation reaction.

Zirconium-catalyzed dimerization of 1,2-dienes in preparation for the synthesis of useful 1,4-diorganomagnesium compounds from 1,2-dienes (Scheme 51) and its application to the synthesis of tricyclic compounds (Scheme 52) was reported [137–143].

Scheme 51.

Synthesis of 1,4-diorganomagnesium compound from 1,2-dienes.

Scheme 52.

Synthesis of tricyclic compounds.

Manganese-catalyzed regioselective allylmetalation of allenes was reported (Scheme 53) [144]. The regioselectivity of the manganese-catalyzed addition reaction was opposite to that of the rhodium-catalyzed reactions, and vinylmagnesium intermediates were formed.

Scheme 53.

Manganese-catalyzed allylmagnesiation of allenes.

Although titanium-catalyzed allylmagnesiation of isoprene was reported in the 1970s, the scope of the reagents was limited to the allylic magnesium reagents [145–146]. Recently, Terao and Kambe reported copper-catalyzed regioselective carbomagnesiation of dienes and enynes using sec- or tert-alkylmagnesium reagents (Scheme 54) [147]. They assumed that the active species were organocuprates and that the radical character of carbocupration enabled bulky sec- or tert-alkylmagnesium reagents to be employed.

Scheme 54.

Copper-catalyzed alkylmagnesiation of 1,3-dienes and 1,3-enynes.

Chromium-catalyzed carbomagnesiation of 1,6-diyne (Scheme 55) [148] and 1,6-enyne (Scheme 56) [149] also provided interesting organomagnesium intermediates through cyclization reactions [150]. Treatment of 1,6-diyne 5j with methallylmagnesium reagent in the presence of chromium(III) chloride afforded bicyclic product 5k in excellent yield. In the proposed mechanism, the chromium salt was firstly converted to chromate 5C by means of 4 equiv of methallylmagnesium reagent (Scheme 57). After the carbometalation followed by cyclization onto another alkyne moiety, vinylic organochromate 5D would be then formed. Subsequent intramolecular carbochromation would provide 5E, and finally transmetalation with methallylmagnesium reagent would give 5l efficiently. The reaction of 1,6-enyne also proceeded through a tetraallylchromate complex as an active species (Scheme 56). However, the second cyclization did not take place.

Scheme 55.

Chromium-catalyzed methallylmagnesiation of 1,6-diynes.

Scheme 56.

Chromium-catalyzed allylmagnesiation of 1,6-enynes.

Scheme 57.

Proposed mechanism of the chromium-catalyzed methallylmagnesiation.

Conclusion

We have summarized the progress in transition-metal-catalyzed carbomagnesiation and carbozincation chemistry that has been made in the past 15 years. Despite the significant advances, there remains room for further improvements with regards to the scope of reagents, selectivity of the reaction, and information about the mechanisms, especially for alkenes as substrates. Further studies will surely provide powerful routes for functionalized multisubstituted alkenes and alkanes from simple alkynes and alkenes with high regio-, stereo-, and ultimately enantioselectivity.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article and parts of the synthetic chemistry in this article were supported by JSPS and MEXT (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, No. 24685007, 23655037, and 22406721 “Reaction Integration”) and by The Uehara Memorial Foundation, NOVARTIS Foundation for the Promotion of Science, and Takeda Science Foundation. K.M. acknowledges JSPS for financial support.

This article is part of the Thematic Series "Carbometallation chemistry".

References

- 1.Grignard V. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1900;130:1322–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J, Velarde-Ortiz R, Guijarro A, Wurst J R, Rieke R D. J Org Chem. 2000;65:5428–5430. doi: 10.1021/jo000413i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piller F M, Appukkuttan P, Gavryushin A, Helm M, Knochel P. Angew Chem. 2008;120:6907–6911. doi: 10.1002/ange.200801968. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2008,47, 6802–6806. doi:10.1002/anie.200801968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knochel P, Almena Perea J J, Jones P. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:8275–8319. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00318-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majid T N, Knochel P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4413–4416. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)97635-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu L, Wehmeyer R M, Rieke R D. J Org Chem. 1991;56:1445–1453. doi: 10.1021/jo00004a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasovskiy A, Malakhov V, Gavryushin A, Knochel P. Angew Chem. 2006;118:6186–6190. doi: 10.1002/ange.200601450. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2006,45, 6040–6044. doi:10.1002/anie.200601450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walborsky H M. Acc Chem Res. 1990;23:286–293. doi: 10.1021/ar00177a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren H, Krasovskiy A, Knochel P. Org Lett. 2004;6:4215–4217. doi: 10.1021/ol048363h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knochel P, Dohle W, Gommermann N, Kneisel F F, Kopp F, Korn T, Sapountzis I, Vu V A. Angew Chem. 2003;115:4438–4456. doi: 10.1002/ange.200300579. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2003,42, 4302–4320. doi:10.1002/anie.200300579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ila H, Baron O, Wagner A J, Knochel P. Chem Commun. 2006:583–593. doi: 10.1039/b510866g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue A, Kitagawa K, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4333–4339. doi: 10.1021/jo015597v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitagawa K, Inoue A, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Angew Chem. 2000;112:2594–2596. doi: 10.1002/1521-3757(20000717)112:14<2594::AID-ANGE2594>3.0.CO;2-O. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2000,39, 2481–2483. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000717)39:14<2481::AID-ANIE2481>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Normant J F, Alexakis A. Synthesis. 1981:841–870. doi: 10.1055/s-1981-29622. (See for carbometalation reactions (including Mg, Zn, Li, Cu, Al) of various alkynes and alkenes.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppolzer W. Angew Chem. 1989;101:39–53. doi: 10.1002/ange.19891010106. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1989,28, 38–52. doi:10.1002/anie.198900381 (See for intramolecular metallo-ene reaction using stoichiometric Li, Mg, Zn and catalytic Ni, Pd, Pt.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto Y, Asao N. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2207–2293. doi: 10.1021/cr00022a010. (See for selective reaction using allylic metals, including allylmagnesiation and allylzincation.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marek I. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1999:535–544. doi: 10.1039/A807060A. (See for asymmetric carbometalation, including carbomagnesiation and carbozincation.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallis A G, Forgione P. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:5899–5913. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00422-7. (See for metal-mediated carbometalation (including Mg, Zn, Bi, Cu, Zr, Li, Si, Sn, In, B, Ga, Al, Ni, Mn) of alkynes and alkenes containing adjacent heteroatoms.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Catal Surv Asia. 2003;7:39–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1023432624548. (See for manganese-catalyzed carbomagnesiation.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:2081–2091. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300757. (See for transition-metal-catalyzed carbon–carbon bond formation with organomagnesium reagents, including carbomagnesiation.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flynn A B, Ogilvie W W. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4698–4745. doi: 10.1021/cr050051k. (See for stereocontrolled synthesis of tetrasubstituted olefins, including carbomagnesiation and carbozincation.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Luna A, Botuha C, Ferreira F, Chemla F. New J Chem. 2008;32:594–606. doi: 10.1039/B716292H. (See for uncatalyzed carbometalation of alkenes with zinc enolates.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terao J, Kambe N. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2006;79:663–672. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.79.663. (See for transition metal-catalyzed C–C bond formation reactions using alkyl halides, including titanium-catalyzed carbomagnesiation.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marek I. Chem–Eur J. 2008;14:7460–7468. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800580. (See for an interesting application of carbometalation intermediates to stereoselective reactions.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basheer A, Marek I. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2010;6:No. 77. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.6.77. (See for a recent review on carbocupration of heteroatom-substituted alkynes including copper-catalyzed and copper-mediated reactions.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura E, Yoshikai N. J Org Chem. 2010;75:6061–6067. doi: 10.1021/jo100693m. (See for iron-catalyzed carbon–carbon bond formation, including carbomagnesiation and carbozincation.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negishi E. Angew Chem. 2011;123:6870–6897. doi: 10.1002/ange.201101380. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2011,50, 6738–6764. doi:10.1002/anie.201101380 (See for Nobel Lecture by Negishi, including carbozincation). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knochel P. Carbometallation of Alkenes and Alkynes. In: Trost B, Fleming I, Semmelhack M F, editors. Additions to and Substitutions at C–C π-Bonds. Vol. 4. New York: Pergamon Press; 1991. pp. 865–911. ((Comprehensive Organic Synthesis)). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marek I, Normant J-F. In: Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Diederich F, Stang P J, editors. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 1998. pp. 271–337. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakefield B J. Organomagnesium Methods in Organic Synthesis. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. Addition of Organomagnesium Compounds to Carbon-Carbon Multiple Bonds; pp. 73–86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marek I, Chinkov N, Banon-Tenne D. Carbometallation Reactions. In: de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. 2nd ed. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2004. pp. 395–478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itami K, Yoshida J-I. Carbomagnesiation Reactions. In: Rappoport Z, Marek I, editors. The Chemistry of Organomagnesium Compounds. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. pp. 631–679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorthiois E, Meyer C. Patai's Chemistry of Functional Groups. Ney York: Wiley; 2009. Carbozincation of Alkenes and Alkynes; p. online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bretting C, Munch-Petersen J, Jørgensen P M, Refn S. Acta Chem Scand. 1960;14:151–156. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.14-0151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corey E J, Katzenellenbogen J A. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:1851–1852. doi: 10.1021/ja01035a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddall J B, Biskup M, Fried J H. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:1853–1854. doi: 10.1021/ja01035a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikai N, Nakamura E. Chem Rev. 2012;112:2339–2372. doi: 10.1021/cr200241f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konno T, Daitoh T, Noiri A, Chae J, Ishihara T, Yamanaka H. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:9391–9404. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2005.07.022. (See for regio-and stereoselective carbocupration of internal acetylenes activated by perfluoroalkyl groups.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie M, Huang X. Synlett. 2003:477–480. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie M, Liu L, Wang J, Wang S. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:4058–4062. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sklute G, Bolm C, Marek I. Org Lett. 2007;9:1259–1261. doi: 10.1021/ol070070b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie M, Lin G, Zhang J, Ming L, Feng C. J Organomet Chem. 2010;695:882–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maezaki N, Sawamoto H, Yoshigami R, Suzuki T, Tanaka T. Org Lett. 2003;5:1345–1347. doi: 10.1021/ol034289b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maezaki N, Sawamoto H, Suzuki T, Yoshigami R, Tanaka T. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8387–8393. doi: 10.1021/jo048747l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sklute G, Amsallem D, Shabli A, Varghese J P, Marek I. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11776–11777. doi: 10.1021/ja036872t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sklute G, Marek I. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4642–4649. doi: 10.1021/ja060498q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marek I, Sklute G. Chem Commun. 2007:1683–1691. doi: 10.1039/b615042j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolodney G, Sklute G, Perrone S, Knochel P, Marek I. Angew Chem. 2007;119:9451–9454. doi: 10.1002/ange.200702981. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2007,46, 9291–9294. doi:10.1002/anie.200702981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Das J P, Chechik H, Marek I. Nat Chem. 2009;1:128–132. doi: 10.1038/nchem.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dutta B, Gilboa N, Marek I. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5588–5589. doi: 10.1021/ja101371x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Das J P, Marek I. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4593–4623. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mejuch T, Botoshansky M, Marek I. Org Lett. 2011;13:3604–3607. doi: 10.1021/ol201221d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mejuch T, Dutta B, Botoshansky M, Marek I. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:5803–5806. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25121c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minko Y, Pasco M, Lercher L, Botoshansky M, Marek I. Nature. 2012;490:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature11569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayashi T, Inoue K, Taniguchi N, Ogasawara M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9918–9919. doi: 10.1021/ja0165234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashi T, Yamasaki K. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2829–2844. doi: 10.1021/cr020022z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakai M, Hayashi H, Miyaura N. Organometallics. 1997;16:4229–4231. doi: 10.1021/om9705113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takaya Y, Ogasawara M, Hayashi T, Sakai M, Miyaura N. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5579–5580. doi: 10.1021/ja980666h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shintani R, Hayashi T. Org Lett. 2005;7:2071–2073. doi: 10.1021/ol0506819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richey H G, Jr, Rothman A M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)98978-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forgione P, Fallis A G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01994-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duboudin J-G, Jousseaume B, Saux A. J Organomet Chem. 1979;168:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)91989-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anastasia L, Dumond Y R, Negishi E. Eur J Org Chem. 2001:3039–3043. doi: 10.1002/1099-0690(200108)2001:16<3039::AID-EJOC3039>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang D, Ready J M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15050–15051. doi: 10.1021/ja0647708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okada K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6076–6077. doi: 10.1021/ja960791y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishimae S, Inoue R, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Chem Lett. 1998:785–786. doi: 10.1246/cl.1998.785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murakami K, Ohmiya H, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Chem Lett. 2007;36:1066–1067. doi: 10.1246/cl.2007.1066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong T, Tjepkema M W, Audrain H, Wilson P D, Fallis A G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:755–758. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(95)02303-8. (See for anti-vinylmagnesiation of propargyl alcohol in the absence of transition-metal catalyst.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Itami K, Kamei T, Yoshida J. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14670–14671. doi: 10.1021/ja037566i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Normant J F, Alexakis A, Commercon A, Cahiez G, Villieras J, Normant J F. C R Seances Acad Sci, Ser C. 1974;279:763–765. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vermeer P, de Graaf C, Meijer J. Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1974;93:24–25. doi: 10.1002/recl.19740930111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meijer J, Westmijze H, Vermeer P. Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1976;95:102–104. doi: 10.1002/recl.19760950504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alexakis A, Cahiez G, Normant J F, Villieras J. Bull Soc Chim Fr. 1977:693–698. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chechik-Lankin H, Marek I. Org Lett. 2003;5:5087–5089. doi: 10.1021/ol036154b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chechik-Lankin H, Livshin S, Marek I. Synlett. 2005:2098–2100. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levin A, Basheer A, Marek I. Synlett. 2010:329–332. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1219221. (See for regiodivergent carbocupration of ynol ether derivatives.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gourdet B, Lam H W. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3802–3803. doi: 10.1021/ja900946h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gourdet B, Rudkin M E, Watts C A, Lam H W. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7849–7858. doi: 10.1021/jo901658v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yasui H, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Chem Lett. 2007;36:32–33. doi: 10.1246/cl.2007.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yasui H, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2008;81:373–379. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.81.373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watkins E K, Richey H G., Jr Organometallics. 1992;11:3785–3794. doi: 10.1021/om00059a048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakamura M, Hirai A, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:978–979. doi: 10.1021/ja983066r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nakamura M, Inoue T, Sato A, Nakamura E. Org Lett. 2000;2:2193–2196. doi: 10.1021/ol005892m. (See for enantioselective allylzincation of cyclopropenone acetal with an allylic zinc reagent bearing a chiral bisoxazoline ligand.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liao L, Fox J M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14322–14323. doi: 10.1021/ja0278234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yan N, Liu X, Fox J M. J Org Chem. 2008;73:563–568. doi: 10.1021/jo702176x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Simaan S, Marek I. Org Lett. 2007;9:2569–2571. doi: 10.1021/ol070974x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Simaan S, Masarwa A, Bertus P, Marek I. Angew Chem. 2006;118:4067–4069. doi: 10.1002/ange.200600556. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2006,45, 3963–3965. doi:10.1002/anie.200600556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang Z, Xie X, Fox J M. Angew Chem. 2006;118:4064–4066. doi: 10.1002/ange.200600531. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2006,45, 3960–3962. doi:10.1002/anie.200600531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simaan S, Masarwa A, Zohar E, Stanger A, Bertus P, Marek I. Chem–Eur J. 2009;15:8449–8464. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu X, Fox J M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5600–5601. doi: 10.1021/ja058101q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tarwade V, Liu X, Yan N, Fox J M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5382–5383. doi: 10.1021/ja900949n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tarwade V, Selvaraj R, Fox J M. J Org Chem. 2012;77:9900–9904. doi: 10.1021/jo3019076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Krämer K, Leong P, Lautens M. Org Lett. 2011;13:819–821. doi: 10.1021/ol1029904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lautens M, Hiebert S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1437–1447. doi: 10.1021/ja037550s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Terao J, Tomita M, Singh S P, Kambe N. Angew Chem. 2010;122:148–151. doi: 10.1002/ange.200904721. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2010,49, 144–147. doi:10.1002/anie.200904721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu Y, Ma S. Chem Sci. 2011;2:811–814. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00584C. (See for an interesting uncatalyzed reaction of 2-cyclopropenecarboxylates with organomagnesium reagents to afford tri-and tetrasubstituted alkenes by carbon–carbon bond cleavage.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Y, Fordyce E A F, Chen F Y, Lam H W. Angew Chem. 2008;120:7460–7463. doi: 10.1002/ange.200802391. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2008,47, 7350–7353. doi:10.1002/anie.200802391 (See for iron-catalyzed carboalumination/ring-opening sequence of cyclopropenes.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duboudin J G, Jousseaume B, Saux A. J Organomet Chem. 1978;162:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)82039-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stüdemann T, Knochel P. Angew Chem. 1997;109:132–134. doi: 10.1002/ange.19971090142. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.1997,36, 93–95. doi:10.1002/anie.199700931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stüdemann T, Ibrahim-Ouali M, Knochel P. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:1299–1316. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(97)10226-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cann R O, Waltermire R E, Chung J, Oberholzer M, Kasparec J, Ye Y K, Wethman R. Org Process Res Dev. 2010;14:1147–1152. doi: 10.1021/op100112r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yorimitsu H, Tang J, Okada K, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Chem Lett. 1998;27:11–12. doi: 10.1246/cl.1998.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yamagami T, Shintani R, Shirakawa E, Hayashi T. Org Lett. 2007;9:1045–1048. doi: 10.1021/ol063132r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shirakawa E, Ikeda D, Masui S, Yoshida M, Hayashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:272–279. doi: 10.1021/ja206745w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ilies L, Yoshida T, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16951–16954. doi: 10.1021/ja307631v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Negishi E, Van Horn D E, Yoshida T, Rand C L. Organometallics. 1983;2:563–565. doi: 10.1021/om00076a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Negishi E, Miller J A. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:6761–6763. doi: 10.1021/ja00360a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Horn D E V, Negishi E. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2252–2254. doi: 10.1021/ja00475a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Suginome M, Shirakura M, Yamamoto A. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14438–14439. doi: 10.1021/ja064970j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Daini M, Suginome M. Chem Commun. 2008:5224–5226. doi: 10.1039/b809433k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shirakawa E, Yamasaki K, Yoshida H, Hiyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:10221–10222. doi: 10.1021/ja992597s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shirakawa E, Yamagami T, Kimura T, Yamaguchi S, Hayashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17164–17165. doi: 10.1021/ja0542136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Matsumoto A, Ilies L, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6557–6559. doi: 10.1021/ja201931e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Murakami K, Ohmiya H, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2007;9:1569–1571. doi: 10.1021/ol0703938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Murakami K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2009;11:2373–2375. doi: 10.1021/ol900883j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tan B-H, Dong J, Yoshikai N. Angew Chem. 2012;124:9748–9752. doi: 10.1002/ange.201204388. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2012,51, 9610–9614. doi:10.1002/anie.201204388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Corpet M, Gosmini C. Chem Commun. 2012;48:11561–11563. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36676b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Murakami K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Chem–Eur J. 2010;16:7688–7691. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nishikawa T, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Synlett. 2004:1573–1574. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-829086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yasui H, Nishikawa T, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2006;79:1271–1274. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.79.1271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kambe N, Moriwaki Y, Fujii Y, Iwasaki T, Terao J. Org Lett. 2011;13:4656–4659. doi: 10.1021/ol2018664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fujii Y, Terao J, Kambe N. Chem Commun. 2009:1115–1117. doi: 10.1039/b820521c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gagneur S, Montchamp J-L, Negishi E. Organometallics. 2000;19:2417–2419. doi: 10.1021/om991004j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dzhemilev U M, Vostrikova O S, Sultanov R M. Izv Akad Nauk SSSR, Ser Khim. 1983:218–220. Russ. Chem. Bull.1983,32, 193–195 doi:10.1007/BF01167793. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Takahashi T, Seki T, Nitto Y, Saburi M, Rousset C J, Negishi E. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6266–6268. doi: 10.1021/ja00016a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Knight K S, Waymouth R M. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6268–6270. doi: 10.1021/ja00016a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Houri A F, Didiuk M T, Xu Z M, Horan N R, Hoveyda A H. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:6614–6624. doi: 10.1021/ja00068a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Visser M S, Heron N M, Didiuk M T, Sagal J F, Hoveyda A H. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:4291–4298. doi: 10.1021/ja960163g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bell L, Brookings D C, Dawson G J, Whitby R J, Jones R V H, Standen M C H. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:14617–14634. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00920-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.de Armas J, Hoveyda A H. Org Lett. 2001;3:2097–2100. doi: 10.1021/ol0160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nii S, Terao J, Kambe N. J Org Chem. 2004;69:573–576. doi: 10.1021/jo0354241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ito S, Itoh T, Nakamura M. Angew Chem. 2011;123:474–477. doi: 10.1002/ange.201006180. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011,50, 454–457. doi:10.1002/anie.201006180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chinkov N, Morlender-Vais N, Marek I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:6009–6010. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01211-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lu Z, Chai G, Ma S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14546–14547. doi: 10.1021/ja075750o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Oisaki K, Zhao D, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7439–7443. doi: 10.1021/ja071512h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yoshida Y, Murakami K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8878–8879. doi: 10.1021/ja102303s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dzhemilev U M, D’yakonov V A, Khafizova L O, Ibragimov A G. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1287–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2003.10.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dzhemilev U M, D’yakonov V A, Khafizova L O, Ibragimov A G. Russ J Org Chem. 2005;41:352–357. doi: 10.1007/s11178-005-0169-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 139.D’yakonov V A, Zinnurova R A, Ibragimov A G, Dzhemilev U M. Russ J Org Chem. 2007;43:956–960. doi: 10.1134/S1070428007070020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140.D’yakonov V A, Makarov A A, Ibragimov A G, Khalilov L M, Dzhemilev U M. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:10188–10194. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.08.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 141.D’yakonov V A, Makarov A A, Ibragimov A G, Dzhemilev U M. Russ J Org Chem. 2008;44:197–201. doi: 10.1134/S1070428008020048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.D’yakonov V A, Makarov A A, Makarova E K, Khalilov L M, Dzhemilev U M. Russ J Org Chem. 2012;48:349–353. doi: 10.1134/S1070428012030025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 143.D’yakonov V A, Makarov A A, Makarova E K, Tyumkina T V, Dzhemilev U M. Russ Chem Bull. 2012;61:158–164. doi: 10.1007/s11172-012-0022-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Nishikawa T, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2003;5:4623–4626. doi: 10.1021/ol035793j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Akutagawa S, Otsuka S. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:6870–6871. doi: 10.1021/ja00856a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Barbot F, Miginiac P. J Organomet Chem. 1978;145:269–276. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)81295-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Todo H, Terao J, Watanabe H, Kuniyasu H, Kambe N. Chem Commun. 2008:1332–1334. doi: 10.1039/b716678h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Nishikawa T, Kakiya H, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4629–4630. doi: 10.1021/ja015746r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nishikawa T, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2002;4:2795–2797. doi: 10.1021/ol026362o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.D’yakonov V A, Tuktarova R A, Dzhemilev U M. Russ Chem Bull. 2011;60:1633–1639. doi: 10.1007/s11172-011-0244-2. (See for zirconium-catalyzed synthesis of magnesacyclopentadienes from α,ω-diynes.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]