Summary

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease which develops in patients with psoriasis. It is characteristic that the rheumatoid factor in serum is absent. Etiology of the disease is still unclear but a number of genetic associations have been identified. Inheritance of the disease is multilevel and the role of environmental factors is emphasized. Immunology of PsA is also complex. Inflammation is caused by immunological reactions leading to release of kinins. Destructive changes in bones usually appear after a few months from the onset of clinical symptoms.

Typically PsA involves joints of the axial skeleton with an asymmetrical pattern. The spectrum of symptoms include inflammatory changes in attachments of articular capsules, tendons, and ligaments to bone surface. The disease can have divers clinical course but usually manifests as oligoarthritis.

Imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis of PsA. Classical radiography has been used for this purpose for over a hundred years. It allows to identify late stages of the disease, when bone tissue is affected. In the last 20 years many new imaging modalities, such as ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR), have been developed and became important diagnostic tools for evaluation of rheumatoid diseases. They enable the assessment and monitoring of early inflammatory changes. As a result, patients have earlier access to modern treatment and thus formation of destructive changes in joints can be markedly delayed or even avoided.

Keywords: psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, imaging studies, genetics and immunology of psoriatic arthritis

Background

Psoriasis is a relapsing inflammatory skin disease that occurs in 1–3% of the world’s population. In Poland, the prevalence of psoriasis is estimated at 2% of the general population. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the major complications associated with psoriasis.

Psoriatic arthritis appears to be a relatively new nosological entity introduced in 1860 by the French physician Pierre Bazin (fr. psoriasis arthritique). More extensive studies on PsA emerged nearly 100 years later – with pioneering work of Vilanova in 1951 and V. Wright in 1961 [1]. The widely accepted definition of the disease and the classification of PsA clinical subgroups was proposed by Moll and Wright in 1973 [2]. The authors defined PsA as „an inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis and negative for serum rheumatoid factor.” Some scientists refused to accept this definition, believing that the condition is a coexistence of two diseases: arthritis (rheumatoid) and psoriasis. Recent discoveries especially in the field of genetics, immunology and epidemiology shed new light on the pathology of the disease. The positive effect of treatment in PsA depends on its early initiation, before progressive joint destruction occurs. Modern diagnostic imaging techniques play a huge role, especially in mildly symptomatic cases.

There are two types of psoriasis: type I with early onset (before 40 years of age) and type II with late onset of symptoms (after the age of 40). Type I is diagnosed in approximately 85% of patients with a peak incidence at the age of 18–22 years [3]. The course of the disease is more severe and often complicated by arthritis. Type I often (85%) coexists with HLA-Cw * 0602 alleles and PSORS1 locus (35–50%) [4]. The contribution of genetic factors is clearly apparent in this type of disease. Type II is a milder form of PsA with a peak incidence at the age of 57–60 years. The correlation with genetic factors is not that evident as in type I. HLA-Cw * 0602 alleles are found only in 15% of cases. Similar results were reported by other authors [5,6]. The course of the disease is less severe and rarely associated with arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory disease in which the cutaneous manifestation of psoriasis coexists with arthritis usually in the absence of rheumatoid factor. The estimated prevalence of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis is 4–42% (typically 7–10%). [7] In more recent studies the prevalence of PsA is more often reported to be approximately 30% among patients with psoriasis, giving an overall prevalence of 0.3–1.0% in the general population [8–10]. The prevalence of PsA in the general population is variable depending on the geographic region and corresponds to the prevalence of psoriasis. The highest rate (1.2%) was reported in Sweden [11].

PsA is a genetic disease arising as a result of the interaction between genetic and environmental factors. The pathogenesis of the disease is not entirely clear. However, there is a strong correlation between the disease and some genetic factors.

In the early publications it was already emphasized that psoriasis occurs more often in first-degree relatives. This suggested that genetic factors are an important part of pathogenesis. A great number of multigenerational family studies as well as epidemiological studies became a support to create a genetic basis of psoriasis. The study by Lamholt et al. investigating the Faroe Islands population as well as the study by Hellgren et al. [12] investigating the Swedish population found a significantly higher familial occurrence of psoriasis. The genetic studies in the 70’s of the last century were focused on the analysis of MHC (Major Histocompatability Complex), which is located on the short arm of chromosome 6 within the 6p21.3 region. This fragment of human genome contains, inter alia, histocompatibility antigens (HLA-human leukocyte antigen) class I and II.

Unlike psoriasis there are no family studies (particularly on siblings) assessing the inheritance of psoriatic arthritis. However, it is generally accepted that PsA is characterized by non-Mendelian transmission, similarly to psoriasis [13].

Immunological studies elucidate the interaction between hereditary and environmental factors in the development of psoriasis and PsA. They also explain the contribution of immune factors to the development of inflammatory lesions. There are two models of pathomechanism leading to the release of inflammatory mediators to the skin and articulations:

Cytokine network model;

Immunocyte/cytokine based model.

In the cytokine network model there are stimulating factors (trauma, infection, some medications), resulting in rapid activation of immunocytes, which set up a cascade of cytokines with tumor necrosis factor (secreted by dermal dendritic cells – macrophages) and interferon gamma (IFN-gamma), secreted by activated Th1 cells [14].

According to the currently most widely accepted immunocyte/cytokine model, the major role in initiating the inflammatory process is played by proteins that disturb signaling between dendritic cells and T cells as well as the alterations of interleukin 23 (IL-23) and other inflammatory mediators.

The manifestation of psoriatic arthritis refers to four main areas: psoriatic skin lesions, the synovial membrane lesions, lesions of tendon and ligament entheses and inflammatory lesions within the bone and cartilage.

Psoriatic skin lesions are closely related to the process of T cell activation. It is confirmed by the positive results of treatment, as mentioned above, with agents blocking certain proteins that are found in the so-called ‘immune synapse’ as well as the induction of similar lesions in animals by an intradermal administration of lymphocytes [15]. A similar effect was obtained using cyclosporine [16].

In patients with psoriatic arthritis the immunological processes occurring in joints are very similar to those in the skin. Lesions appear in the deep layer of the synovial membrane, in which the synovial cells begin to proliferate. Inflammatory infiltrations of synovium are composed mainly of mononuclear cells that are memory-T cells, whereas in the synovial fluid T helper cells predominate. The histopathological images of PsA reveal more intensive hyperaemia as compared to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) .

Inflammatory lesions of tendon and ligament entheses are typical in psoriatic arthritis and other spondyloarthropathies (SpA) [2]. Magnetic Resonance imaging along with a detailed analysis of the anatomy of insertion sites lead to the conclusion that enthesis should be considered as a ‘functional organ’ composed of dense fibrous tissue corresponding to the terminal portion of the tendon, uncalcified fibrocartilage, calcified fibrocartilage and the adjacent bone (Figure 1). MR imaging of enthesitis reveals inflammatory changes of all four parts of attachment site [17].

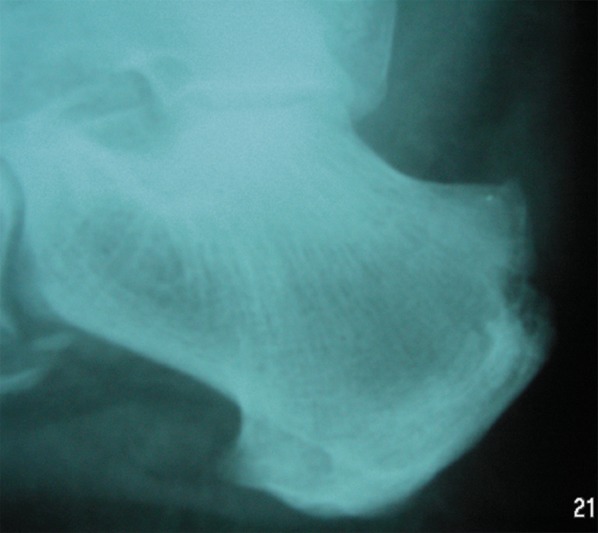

Figure 1.

X-ray of the heel: Destructive changes at the sight of calcaneal tendon attachment due to inflammation.

Psoriatic lesions of articular cartilage manifests as cartilage thinning which leads to joint space narrowing. The process of bone destruction may lead to a major distortion of the articular surfaces and, in extreme cases, may result in a ‘pencil-in-cup’ deformity with joint space widening.

The factors that initiate the psoriatic lesions are often injuries and infections (streptococcal, HIV). Koebner phenomenon related to the effect of mechanical trauma has long been known. First symptoms of the disease often manifest after a streptococcal infection. Other factors triggering PsA include endocrine disorders, certain medications (lithium, antimalarials, quinidine, beta-blockers), alcohol and tobacco smoking [18].

The Clinical Manifestation of PsA

In the 60’s and 70’s five clinical forms of PsA were distinguished by Moll and Wright:

The classic course of the disease with involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints (5% of cases).

Destructive form of arthritis (arthritis mutilans) (5% of cases) (Figures 2 and 3).

Symmetric polyarthritis indistinguishable from rheumatoid arthritis with a negative rheumatoid factor (approximately 15% of cases).

Asymmetric form involving a few interphalangeal joints (also distal) and metacarpophalangeal joints. It is the most common form of arthritis in psoriasis (approximately 70% of all cases).

A form resembling ankylosing spondylitis (5% of cases).

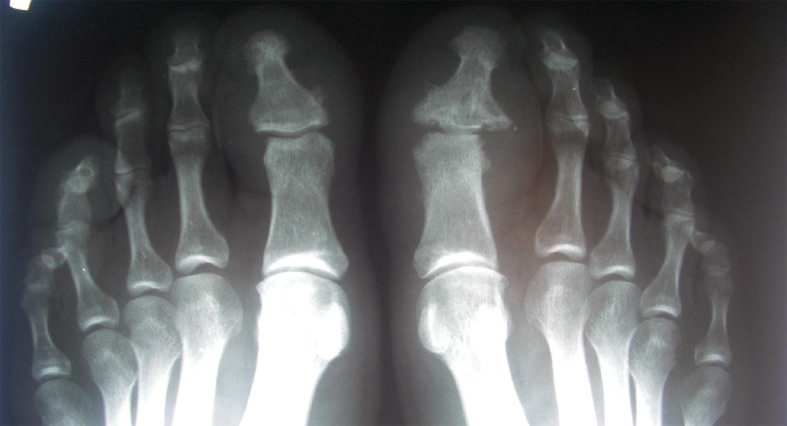

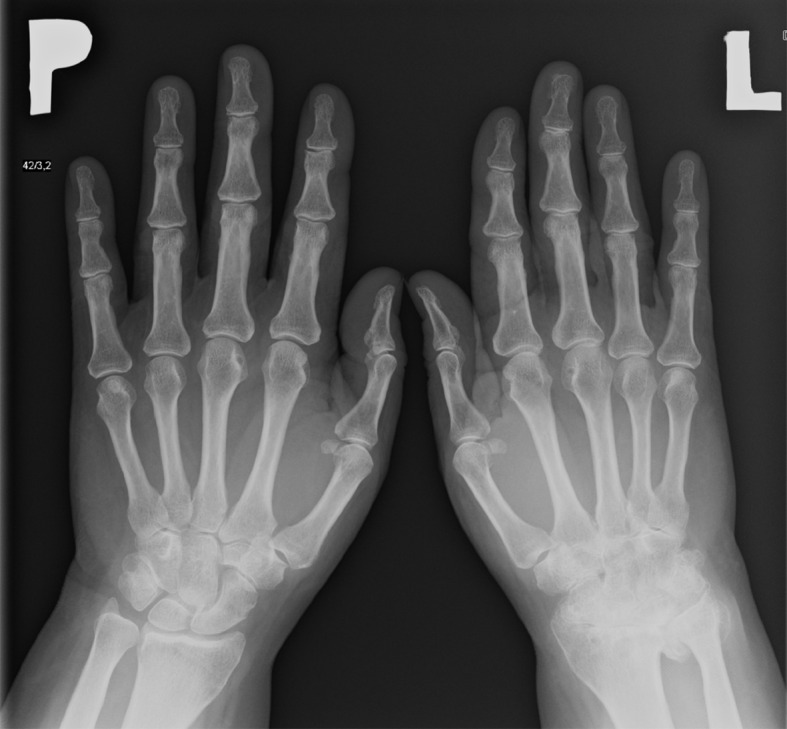

Figure 2.

X-ray of feet: The destructive form of psoriatic arthritis (arthritis mutilans). Numerous destructive changes in matacarpophalangeal and intrerphalangeal joints.

Figure 3.

X-ray of hands: The destructive form of psoriatic arthritis (arthritis mutilans). Numerous destructive changes in joints of both hands. Ankylosis of the right wrist. Typical for PsA changes called “pencil-in-cup” involving metacarpophalangeal joints.

A group of diseases with similar clinical manifestation called seronegative spondyloarthropathies (SpA) has also been defined [19]. The group includes:

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA).

Spondylitis with associated bowel disease (or enteropathic spondylitis).

Reactive arthritis.

Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies.

To support the diagnosis of seronegative spondyloarthropathies, the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) created some clinical criteria. Basing on these criteria the assessment includes the following features:

Inflammatory back pain.

Arthritis.

Positive family history.

Psoriasis.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Buttock pain.

Enthesitis.

Episodes of acute diarrhea.

Urethritis.

Sacroiliitis.

The clinical manifestation of PsA is quite distinctive and different from RA. In most cases (except for the destructive form) the course is less severe than rheumatoid arthritis [20]. The involvement of the spinal joints and sacroiliac joints is typical for PsA. The lesions are characteristic for diseases included in the SpA group [21]. In PsA spinal lesions and sacroiliac joints lesions show significant asymmetry. (Figures 4 and 5). The most common form of the disease is the one involving a few joints of the peripheral skeleton with a distinct asymmetry of symptoms (Figure 6). Involvement of the smaller joints of the hands and feet, especially distal interphalangeal joints, seems to be a characteristic feature. These lesions are accompanied by proliferative lesions of bone tissue located at erosion margins (Figure 7). This is a very characteristic symptom not found in rheumatoid arthritis.

Figure 4.

Inflammatory changes in sacroiliac joints. Marked asymmetry with more prominent erosions on the left side.

Figure 5.

X-ray of sacroiliac joints and lumbar spine. Marked asymmetry of symptoms is visible.

Figure 6.

X-ray of intrerphalangeal joints of the hand. Minor erosive changes involving distal interphalangeal joints.

Figure 7.

Patient with PsA – X-ray of forefoot. Shows a form of the disease involving distal interphalangeal joints. Margin erosions and periostosis in DIP joint of the first finger of the left foot are visible.

The prognosis in psoriatic arthritis is more favorable and the course of the disease is less severe as compared to rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnostic Imaging Methods

Conventional radiography (x-ray) is nowadays widely used as an imaging technique in inflammatory diseases of the osteoarticular system. Nevertheless, it has some limitations in the assessment of soft tissue lesions. The radiological examination is found to be ineffective when it comes to identifying the cause of periarticular soft tissues thickening. X-ray images of synovial hypertrophy, tendinitis and tenosynovitis, intra-articular effusions, esthesitis, or inflammatory lesions of synovial bursa are very much alike and often difficult to distinguish. In case of inflammatory or traumatic effusion a displacement of articular fat tissue caused by an increasing exudate or synovial hypertrophy can be visualized [22,23]. Asymmetrical periarticular oedema can be seen in gout and in the presence of tophi. Inflammatory lesions in the early stages of the disease involve synovial membrane and periarticular tissues. Using conventional radiography these lesions often remain unrevealed, whereas they can be effectively visualized by ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging [24]. These facts point to a higher efficacy of ultrasound and MR imaging in the assessment of soft tissues [25–27].

Soft tissue calcifications typical for crystal arthropathies are visible in the X-ray as amorphous calcifications that occur at the late stage of the disease and require a differential diagnosis including gout and systemic sclerosis.

In PsA with erosions the osteophytes surrounding the erosion are visible, which is quite a typical feature of late PsA.

As cartilage does not absorb X-rays the assessment of articular cartilage in conventional radiography can be obtained only indirectly through the evaluation of joint space width. The radiographic evaluation of joint space width is still considered to be a valuable method to detect joint lesions [28–30]. Narrowing of the joint space reflects the thinning of articular cartilage. The joint space width in PsA remains preserved until the late stage of the disease (similarly to patients with gout) [23,31]. An important part of the joint space assessment is to establish whether the alterations of width are focal or uniform. Uniform narrowing of joint space is more characteristic for inflammatory lesions, while the focal changes are more common in degenerative lesions. These changes are pronounced mainly in the interphalangeal joints as well as the knee and hip joint. Total loss of joint space (complete destruction of cartilage) can be present in the final stages of the inflammatiory process and may suggest ankylosis (Figures 8 and 9). Measurements of joint space narrowing significantly depend on the image projection [31,32].

Figure 8.

X-ray of hands: Ankylosis of the left wrist in a patient with the late stage of PsA.

Figure 9.

Hand X-ray examination: Superimposed degenerative and inflammatory changes in the course of psoriatic arthritis involving the interphalyngeal joints.

The subchondral and periarticular bone can also be assessed using conventional radiological techniques. Erosions are the substantial lesions in this region associated with inflammation. They can be classified as central, marginal, and periarticular according to their location. The degenerative process in inflammatory diseases usually begins at the articular cartilage margin gradually progressing towards the subchondral bone. Radiographic examination can reveal erosions after a few months from the onset of inflammatory process involving the joint. Usually, these lesions can be found earlier using ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which are more sensitive methods than X-ray [33].

Conventional radiography also allows for the assessment of subchondral bone density. The appearance of periarticular bone with distinct osteoporosis in the course of rheumatoid arthritis is widely recognized. The radiographic picture of periarticular bone in PsA is non-specific. The authors reported various manifestation from total lack of symptoms to severe generalized osteoporosis [34]. No severe osteopenia is reported in PsA according to most of the publications. Demineralization of bone structure, however, is a poor prognostic factor in psoriatic arthritis [33].

The most important radiological classification of PsA is PARS (Psoriatic Arthritis Rating Score) evaluating destructive lesion (erosions) in joints and bone proliferation [35]. The assessment includes:

Destruction of the joint (0–5 points).

Evaluation of proliferative lesions (0–4 points).

Overall score in this method ranges from 0 to 360 points. Interphalangeal joints were also evaluated using this method as they are often damaged in the course of PsA.

The progression or regression of joint lesion may also be assessed using PARS which can be useful in monitoring the effectiveness of treatment.

Ultrasonography

To examine large joints such as the knee joint or shoulder joint 5–7,5 Mhz ultrasound transducers can be used. Smaller carpal joints require the use of transducers with frequencies above 10 MHz. [36].

The grayscale ultrasound scanning used for rheumatological diagnosing provides a possibility to visualize the intraarticular effusion and synovial hypertrophy [37]. Intraarticular effusion appear as an anechoic area deformable under probe compression, whereas synovial hypertrophy takes a form of intraarticular masses with echogenicity comparable to soft tissues and non-compressible. An ultrasound scan is a sensitive method for detecting the formentioned lesions and is comparable to magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic examination [38–43]. There are reports in the literature regarding the quantitative evaluation of synovial hypertrophy by measuring the thickness of the synovial folds. Synovial fold thickness over two millimeters in the radiocarpal joints, metacarpophalangeal joints (1 mm) and the elbow joint is considered a confirmation of synovial hypertrophy [38]. Furthermore, if the effusion is visualized, an ultrasound guided joint biopsy and aspiration of the joint effusion for laboratory testing can be performed [44].

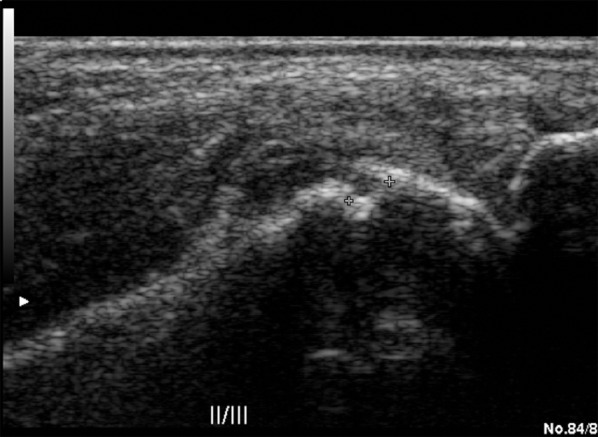

The assessment of destructive bone lesions in ultrasound scanning is subject to some limitations. Large, superficial erosions are relatively well detected, appearing as a discontinuity of regular bone margins filled with tissue of echogenicity similar to synovium. A confirmation of erosive lesions in two perpendicular planes is required in ultrasound examination. The assessment of articular cartilage by ultrasound scanning is limited due thickness calcifications within the basal layer of hyaline cartilage. The width of this layer is not taken into account with an ultrasound study. As a result, the joint space measured by conventional radiography may appear wider [45] (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The US examination in a grey scale, longitudinal plane. Investigation of the second matacarpophalangeal joint. Erosion and inflammatory changes presenting as a synovium hypertrophy.

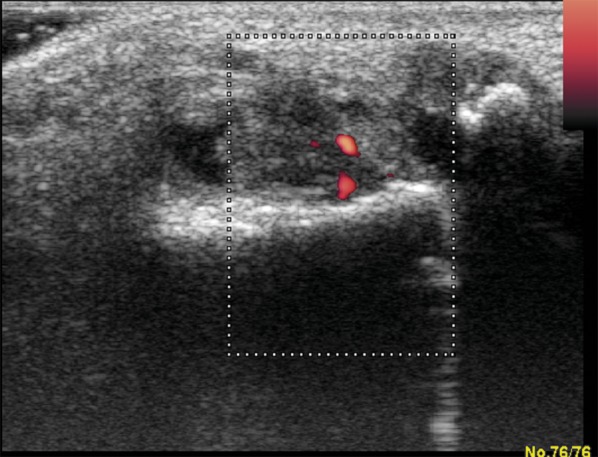

The use of Doppler techniques (colour Doppler and power Doppler) provides the possibility to visualize the hyperaemia of inflammatory lesions in synovium. It should be noted that the images obtained by power Doppler (PD) technique are closely related to the quality of the equipment used and the experience of the physician. Appropriate results can be achieved using standardized settings and methodology of examination. PD technique properly visualizes slow flow in soft tissue. With modern equipment, flow below 10 dB can be detected. This cannot be achieved using color Doppler (CD) technique. On the other hand, PD, unlike CD, does not provide the direction and velocity of blood flow in the vessel (Figure 11). Another disadvantage of this technique are motion artifacts from examined tissue [46]. Despite these limitations, the PD method provides slow flow detection, allowing the visualization of increased vascularity within inflamed tissues [47].

Figure 11.

US examination in the same patient (Figure 7). Effusion, hypertrophy and hyperaemia of synovial membrane with erosions in interphalangeal joint of the left hallux.

This method has been applied in rheumatology for semi-quantitative assessment of inflammatory process activity (synovial hyperemia). By assessing the degree of hyperemia of synovial membranes (or other periarticular structures) one can monitor the effectiveness of treatment using appropriate anti-inflammatory drugs. Another way to assess the severity of inflammation using Doppler techniques is to determine the number of colored pixels within the Doppler gate and to compare the quantity of pixels before and after treatment. Images are subsequently subject to computer processing This method is highly dependent on the equipment, but it is not influenced by the experience of the physician [48]. The evaluation of treatment effectiveness is also possible using spectral Doppler, that was applied earlier on in obstetrics and transplantology to assess the peripheral flow resistance based the resistive index (RI). Normal peripheral blood flow in osteoskeletal system demonstrates high values of resistive index. The diastolic phase of blood flow is usually not observed (RI=1.00). The blood flow resistance within inflamed synovium decreases. On the contrary, an evident normalization of RI values is observed as the effect of treatment [49].

Under normal circumstances, the flow of high-resistance spectrum is always visible in muscle tissue and fascia of the limbs. The flow in normal synovial membrane (nonhyperemic) rarely can be detected using Doppler techniques. In normal tendons and entheses the flow remains undetectable [37].

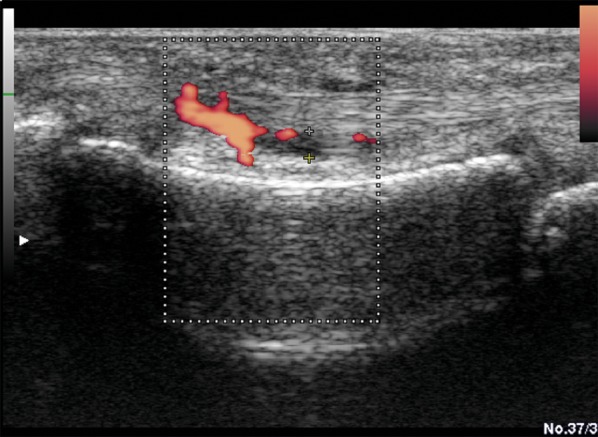

Ultrasonography also allows the detection of inflammatory changes in tendon attachments, ligaments and tendon sheaths. Lesions within these structures, as mentioned above, are characteristic of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Grayscale ultrasound displays thickening of the enthesis as well as its heterogeneous structure. In addition, there are bone lesions (destructive) visible near the enthesis that are a late manifestation of inflammatory process [50]. Using CD or PD technique hyperemia of the inflamed enthesis can be visualized [51] (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

US examination Power Doppler of the proximal phalanx of the II finger, volar side. Inflammatory changes in the tendon sheath of the flexor muscle of the fingers. Joint effusion, synovial membrane hypertrophy and hyperaemia in PD.

The introduction of contrast agents resulted in further development in diagnostic ultrasound of the osteoarticular system. The use of harmonic imaging and pulse inversion techniques combined with low mechanic index prevents contrast microvesicles from breakage and destruction. Initially, contrast agents of first generation containing air were applied. The second-generation contrast – SonoVue (Bracco, Italy) is available now on the domestic market, with microvesicles sized 3 to 7 microns filled with gas (sulfur fluoride) coated with a phospholipid sheath.

After intravenous administration of SonoVue the distribution of contrast microvesicles in the microcirculation can be observed in real time, providing a dynamic assessment of tissue and pathologic lesion vascularity. Intravenous administration of a contrast agent results in a substantial increase of sensitivity of Doppler imaging techniques and often provides a possibility to visualize flow in normal synovium.

These techniques are helpful to distinguishing synovial inflammation and non-inflammatory processes. Ultrasound contrast agents are very expensive, thus, in our laboratories they are mainly used for experimental purposes. More detailed imaging of periarticular structures became available using spatial imaging techniques (3D and 4D).

These studies provide early detection of erosions and inflammatory lesions of tendon insertion sites. Spectacular images were obtained using spatial imaging in partial or complete tendon rupture.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

High-resolution tissue imaging allows a simultaneous assessment of different structures of both osteoskeletal system and soft tissue [24]. MRI resolution capability exceeds all other imaging techniques used in diagnostics of the musculoskeletal system. Despite this undoubted advantage of magnetic resonance, it is still time-consuming and an expensive method [23,53]. Currently, most scanners used in rheumatologic diagnostics are 1.5 T devices. (There are also 3.0 T scanners available). More detailed images can be obtained using this equipment, particularly investigating small bony structures within the wrist [54].

To examine the osteoarticular system the following sequences are most commonly used: spin-echo sequence (SE) and fast spin-echo (FSE), gradient echo (GRE) and fat-saturation sequences. Proper assessment of joints using this method must be based on perfect knowledge of normal anatomy of the investigated joints [22,33]. Different structures within the joint as well as periarticular structures produce different images, depending on the sequence in MRI [55].

Normal muscle tissue has an intermediate signal intensity on T1- and T2-weigted images. Muscle edema occurring in inflammatory diseases increases the signal intensity of muscle structures in all spin-echo images. Differential diagnosis of such finding using fat-saturation sequence (STIR) includes symptoms of fatty infiltration with increased amount of fat resulting in a high signal intensity [56].

All the ligaments and tendons reveal low signal intensity on gradient echo sequence and all spin-echo sequences. Inflammatory lesions significantly increase the signal intensity of these structures [57]. Similar MR images are observed in normal entheses. Normally entheses are visualized as low signal structures, whereas in enthesitis the intensity of signal increases (e.g. SpA lesions or overload-related lesions). In cases of inflammation imaging usually reveals coexisting edema of bony structures adjacent to the enthesis. This is evident on T2-weighted images and fat-saturation sequences (STIR, FATSAT) [58].

Normal hyaline cartilage has a low signal on spin-echo images (SE) and high signal on gradient echo sequences (T2). High signal intensity in gradient sequences generates good contrast between cartilage (high signal) and subchondral bone (low signal). Heterogeneous MRI signal of hyaline cartilage and an increased signal of cartilage on T1-weighted images, particularly the signal alteration in the gradient echo sequence indicates the presence of degenerative lesions. Cartilage pathology can be visualized as a cavity, irregular margins or thickness reduction [36]. This leads to a narrowing of the joint space, which can be well depicted on magnetic resonance images [59,60]. In contrast to the hyaline cartilage, intra-articular fibrocartilage (meniscus, triangular cartilage) has a low signal in all sequences [61]. The assessment of triangular cartilage is less significant in inflammatory diseases of the osteoarticular system, as it is a part of the wrist often suffering from traumatic damage or degeneration [62,63].

In inflammatory (rheumatic) diseases involving joints the assessment of the synovial membrane is particularly important. Factors causing damage to synovial membranes, which are not fully recognized, lead to the activation of the complement and other biologically active agents described above. These alterations result in hyperemia and synovial hypertrophy. Kinins produced by the inflamed synovium (pannus) lead to inflammatory lesions in the surrounding tissues. For a thorough evaluation of pannus the following diagnostic protocol has been suggested: T1-weigted images in the coronal and axial plane, followed by T2-weighted images with fat saturation in the axial plane. The final phase of examination includes T1-weighted images with fat saturation in the coronal plane performed after intravenous administration of a contrast agent [64].

The synovial membrane is a well-vascularized tissue. Hence, after administration of contrast agent significant contrast enhancement is observed, providing detailed imaging of the synovial size. Visualization of synovial membrane enables follow-up examinations and therapy monitoring [65]. Two methods are used to evaluate the activity of the inflammatory process. The former is to measure the synovial volume, particularly in larger joints. The latter involves the measurement of signal intensity curve after contrast agent administration. To assess the effectiveness of treatment follow-up examinations are compared. In addition, contrast agent administration helps distinguish inflammatory process of synovial membrane from inactive fibrotic synovium (treatment outcome) (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

MR examination of the joints of the wrist. STIR images. The distal radio-ulnar joint effusion, less prominent in intercarpal joints.

Isotope Examination

Scintigraphic examination is widely performed in patients with inflammatory joint diseases as a useful method of evaluating bone metabolism. It is based on the evaluation of an intense accumulation of radioisotope in areas of increased metabolism within the inflamed joints. Isotope examination is a very sensitive method providing assessment of joints in a whole- body imaging in a single examination. This method however is limited due to its low specificity.

A variety of different factors may cause increased accumulation of isotope within the joint. Differentiation usually requires the use of other imaging techniques and diagnostic analyses (Figures 14 and 15).

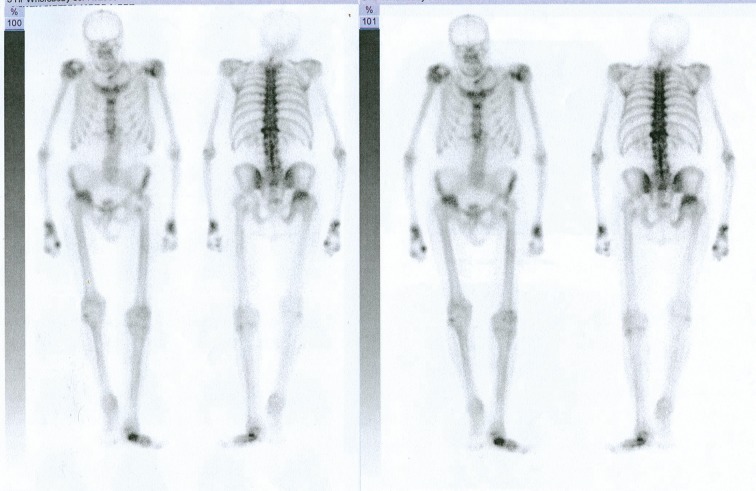

Figure 14.

Whole body Scintigraphy (of skeleton) of a patient with PsA. Numerous joints of axial and peripheral skeleton involved in the process.

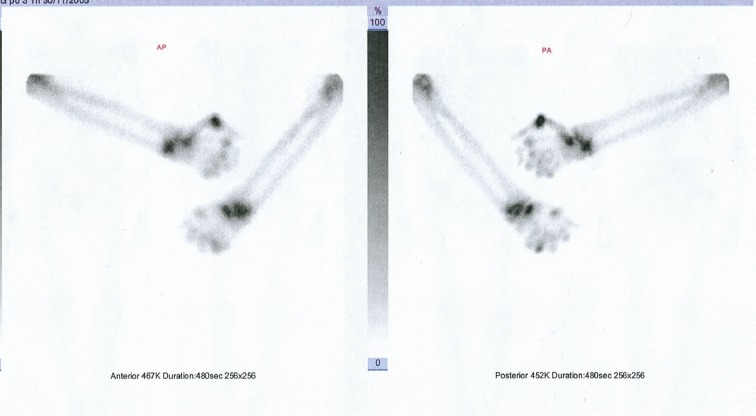

Figure 15.

Scintigraphy of hands and forearms. Radionuclide accumulation in the joints of the wrist, metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints involved in the inflammatory process.

Several different isotopes are utilized for diagnostic procedures in the assessment of the osteoarticular system. Technetium 99m (99mTc) is commonly used. This isotope however is characterized by low specificity. Gallium67 (67Ga), widely used in the diagnosis of neoplastic lesions, demonstrates comparably higher specificity. 67Ga binds to transferrin and is selectively taken up by tumor cells. The most advantageous isotope for diagnosing bone inflammation is indium 111, labeling leukocytes.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is a modern imaging technique utilizing X-rays to detect lesions. High-resolution CT provides detailed structural assessment of the osteoarticular system. In rheumatology it enables the assessment of bony structures. This method is also effective in assessing the axial skeleton joints (sacroiliac joints, spinal joints). Computed tomography demonstrates substantially higher effectiveness as compared to conventional radiography, particularly considering the assessment of sacroiliac joints.

Destructive lesions within these joints are often appear on X-ray images after many years of the disease (PsA, AS). CT is able to visualize these changes after a few months. This also applies to peripheral joints. Erosive lesions appear much much earlier then they would on conventional X-ray examinations.

High-resolution CT scanning is considered the most effective in the assessment of calcifications, proliferative lesions of bones as well as erosive lesions in rheumatic diseases.

Suggested Diagnostic Algorithm

Lesions suspected of polyarthritis (PsA)

- Early lesions period (0–6 months).

- Isotope examination:

- – Ultrasound examination of joints found to be abnormal on isotope examination;

- – Hand X-ray (initial radiographs).

- MRI:

- – In case of equivocal ultrasound;

- – Lesions involving axial skeleton (CT alternatively).

- Later period (over 6 months).

- Monitoring of treatment:

- – Ultrasound of abnormal joints;

- – Scintigraphy/ultrasound/MRI (alternatively) in case of symptoms suggesting the involvement of other joints.

- Follow-up hand X-ray after 2 years.

- Advanced lesions.

- Bilateral hand X-ray examination (if involved) every 2 years.

- Ultrasound for monitoring activity of the inflammatory process.

- Magnetic resonance imaging in case of axial skeleton involvement.

References:

- 1.Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. A comparative radiographic study of rheumatoid arthritis and arthritis associated with psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1961;20:123. doi: 10.1136/ard.20.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moll JMH, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1973;3(1):55–78. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(73)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hensler T, Christophers E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: characterization of two types of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(3):450–56. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen MH, Ameen H, Veal C, et al. The Major Psoriasis Susceptibility Locus PSORS1 Is not a Risk Factor for Late-Onset Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:103–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veale D, Rogers S, Fitzgerald O. Classification of Clinical Subsets in Psoriatic Arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:133–38. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langley RGB, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:18–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Heresh AM, Proctor J, Jones SM, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha polymorphism and the HLA-Cw*0602 allele in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology. 2002;41:525–30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarpa R, Oriente P, Pucino A, et al. Psoriatic arthritis in psoriatic patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1984;23(4):246–50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/23.4.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvarani C, Lo Scocco G, Macchioni P, et al. Prevalence of Psoriatic Arthritis in Italian Psoriatic Patients. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(8):1499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green L, Meyers OL, Gordon W, et al. Arthritis in Psoriasis. Ann Reum Dis. 1981;40(4):366–69. doi: 10.1136/ard.40.4.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellgren L. Association Between Rheumatoid Arthritis and Psoriasis in Total Populations. Acta Rheumatol Scand. 1969;15:316–26. doi: 10.3109/rhe1.1969.15.issue-1-4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellgren L. Morphology, inheritance and association with other skin and rheumatic diseases. Almquist and Wiksell; Stockholm: 1967. The prevalance in sex, age and occupational groups in total populations in Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahman P, Gladman DD, Schentag C, et al. Excessive paternal transmission in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) Arthritis Rheumatica. 1999;42:1228–31. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1228::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nickoloff BJ. The immunologic and genetic basis of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1104–10. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.9.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wrone-Smith T, Nickloff BJ. Dermal injection of immunocytes induces psoriasis. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1878–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI118989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jan V, Vaillant L, Bressieux JM, et al. Short-term cyclosporin monotherapy for chronic severe plaque-type psoriasis. Eur J Dermatoil. 1999;8(9):815–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benjamin M, McGonagle D. The anatomical basis for disease localization in seronegative spondyloarthropathy at entheses and related sites. J Anat. 2001;199:503–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19950503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters BP, Weissman FG, Gill MA. Pathophysiology and treatment of psoriasis. American Journal Health-System Pharmacy. 2000;57:645–59. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.7.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright V. Seronegative polyarthritis: a unified concept. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21(6):619–33. doi: 10.1002/art.1780210603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gladman D D, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:ii14–ii17. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keat A. ABC of Rheumatology: SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES. The BMJ. 1995;310:1321–24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6990.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The J, Sukumar V, Jackson S. Imaging of the elbow. Imaging. 2003;15:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grainger AJ, McGonagle D. Imaging in rheumatology. Imaging. 2003;15:286–97. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Backhaus M, Kamradt T, Sandrock D, et al. Arthritis of the finger joints: a comprehensive approach comparing conventional radiography, scintigraphy, ultrasound, and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1232–45. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1232::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciechomska A, Andrysiak R, Serafin-Król M, et al. Ocena przydatności ultrasonografii i rezonansu magnetycznego w diagnostyce zapalenia stawów rąk. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski. 2001;62:144–47. [in Polish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Simone C, Caldarola G, D’Agostino M, et al. Usefulness of ultrasound imaging in detecting psoriatic arthritis of fingers and toes in patients with psoriasis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:396. doi: 10.1155/2011/390726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wittoek R, Lans L, Lambrecht V, et al. Reliability and construct validity of ultrasonography of soft tissue and destructive changes in erosive osteoarthritis of the interphalangeal finger joints: a comparison with MRI. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(2):278–83. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichmann WM, Maillefert JF, Hunter DJ, et al. Responsiveness to change and reliability of measurement of radiographic joint space width in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(5):550–56. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moller B, Bonel H, Rotzetter M, et al. Measuring finger joint cartilage by ultrasound as a promising alternative to conventional radiographs imaging. Arthritis Care Rea. 2009;61(4):435–41. doi: 10.1002/art.24424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eckstein F, Le Graverand MP, Charles HC, et al. Clinical, radiographic, molecular and MRI-based predictors of cartilage loss of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(7):1223–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.141382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agnesi F, Amrami KK, Frigo CA, et al. Comparison of cartilage thickness radiologic grade of knee osteoarthritis. Skeletal Radiology. 2008;37(7):639–43. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0483-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nevitt MC, Paterfy C, Guermazi A, et al. Longitudinal performance evaluation and validation of fixed-flexion radiography of the knee for detection of joint space loss. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1512–20. doi: 10.1002/art.22557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Backhaus M, Burmester GR, Sandrock D, et al. Prospective two year follow up study comparing novel and conventional imaging procedures in patients with arthritic finger joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:895–904. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.10.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison BJ, Hutchinson CE, Adams J, et al. Assessing periarticular bone mineral density in patients with early psoriatic arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:1007–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.11.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Heijde D, Sharp J, Wassenberg S, et al. Psoriatic arthritis imaging: a review of scoring methods. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:61–64. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.030809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kane D, Balint PV, Sturrock R, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound-a state of art. Review in rheumatology. Part 1: Current controversies and issues in the development of musculoskeletal ultrasound in rheumatology. Rheumatology. 2004;43:823–28. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terslev I, Torp-Pedersen S, Qvistgaard E, et al. Doppler Ultrasound findings in healthy wrists and finger joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:644–48. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naredo E, Bonilla G, Gamero F, et al. Assessment of inflammatory activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a comparative study of clinical evaluation with grey scale and power Doppler ultrasonography. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:375–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.023929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cimmino MA, Barbieri F, Zampogna G, et al. Imaging in arthritis: quantifying effects of therapeutic intervention using MRI and molecular imaging. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012:141. doi: 10.57187/smw.2012.13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Hayashi D. Imaging of osteoarthritis: update from a radiological perspective. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(5):484–91. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain M, Samuels J. Musculoskeletal ultrasound in the diagnosis of rheumatic disease. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2010;68(3):183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horikoshi M, Suzuki T, Sugihara M, et al. Comparison of low-field dedicated extremity magnetic resonance imaging with articular ultrasonography in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Modern Rheumatology/the Japan Rheumatism Association. 2010;20(6):556–60. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapuścińska K, Urbanik A, Wojciechowski W, et al. Stardardisation of the MRI and US images evaluation in the diagnostics of rheumatoid arthritis within the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints. Przegląd Lekarski. 2010;67(4):318–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raza K, Lee CY, Piling D, et al. Ultrasound guidance allows accurate needle placement and aspiration from small joints in patients with early inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology. 2003;42:976–79. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moller B, Bonel H, Rotzetter M, et al. Measuring finger joint cartilage by ultrasound as a promising alternative to conventional radiographs imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(4):435–41. doi: 10.1002/art.24424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bude RO, Rubin JM. Power Doppler Sonography. Radiology. 1996;200:21–23. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.1.8657912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newman JS, Laing TJ, McCarthy CJ, et al. Power Doppler Sonography of Synovitis: Assessment of Therapeutic Response – Preliminary Observations. Radiology. 1996;198:582–84. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.2.8596870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terslev L, Torp-Pedersen S, Qvistgaard E, et al. Estimation of inflammation by Doppler ultrasound: quantitative changes after intra-articular treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1049–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.11.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qvistgaard E, Rogind H, Torp-Pedersen S, et al. Quantitative ultrasonography in rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation of inflammation by Doppler technique. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:690–93. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.7.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grassi W, Cervini C. Ultrasonography in rheumatology: an evolving technique. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1998;57:268–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.5.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balint P V, Kane D, Wilson H, et al. Ultrasonography of entheseal insertions in the lower limb in spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:905–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.10.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McQueen F M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in early inflammatory arthritis: what is its role? Rheumatology. 2000;39:700–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.7.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taouli B, Zaim S, Peterfy CG, et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand and Wrist: Comparison of Three Imaging Techniques. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:937–43. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.4.1820937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saupe N, Prussmann KP, Luechinger R, et al. MR Imaging of the Wrist: Comparison between 1,5- and 3-T MR Imaging – Preliminary Experience. Radiology. 2005;234:256–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341031596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burgener F A, Meyers S P, Tan R K, et al. Differential Diagnosis in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Thieme. 2002:354–63. Section IV: [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hernandez RJ, Keim D, Chenevert TL, et al. Fat-suppressed MR Imaging of Myositis. Radiology. 1992;182:217–19. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McLoughlin RF, Raber EL, Vellet AD, et al. Patellar Tendinitis: MR Imaging Features, with Suggested Pathogenesis and Proposed Classification. Radiology. 1995;197:843–48. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.3.7480766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGonagle D. Imaging the Joint and Enthesis: Insights into Pathogenesis of Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:58–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haugen IK, Lillegraven S, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, et al. Hand osteoarthritis and MRI: development and first validation step of the proposed Oslo Hand Osteoarthritis MRI score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):1033–38. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yi-Xiang JW, Gryffith JF, Ahuja AT. Non-invasive MRI assessment of the articular cartilage in clinical studies and experimental settings. World J Radiol. 2010;2(1):44–54. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oneson SR, Scales LM, Erickson SJ, et al. MR Imaging of the Painful Wrist. RadioGraphics. 1996;16:997–1008. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.16.5.8888387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kang HS, Kindynis P, Brahme SK, et al. Triangular Fibrocartilage and Intercarpal Ligaments of the Wrist: MR Imaging. Radiology. 1991;181:401–4. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.2.1924779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schweitzer ME, Brahme SK, Hodler J, et al. Chronic Wrist Pain: Spin-Echo and Short Tau Inversion Recovery MR Imaging and Conventional and MR Arthrography. Radiology. 1992;182:205–11. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McQueen FM, Stewart N, Crabbe J, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Wrist in Early Rheumatoid arthritis Reveals a High Prevalence of Erosions at Four Mounths After Symptom Onset. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:350–56. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.6.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weger W. An update on the diagnosis and management of psoriatic arthritis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011;146(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]