Abstract

Problem addressed

The growing number of elderly patients with multiple chronic conditions presents an urgent challenge in primary care. Current practice models are not well suited to addressing the complex health care needs of this patient population.

Objective of program

The primary objective of the IMPACT (Interprofessional Model of Practice for Aging and Complex Treatments) clinic was to design and evaluate a new interprofessional model of care for community-dwelling seniors with complex health care needs. A secondary objective was to explore the potential of this new model as an interprofessional training opportunity.

Program description

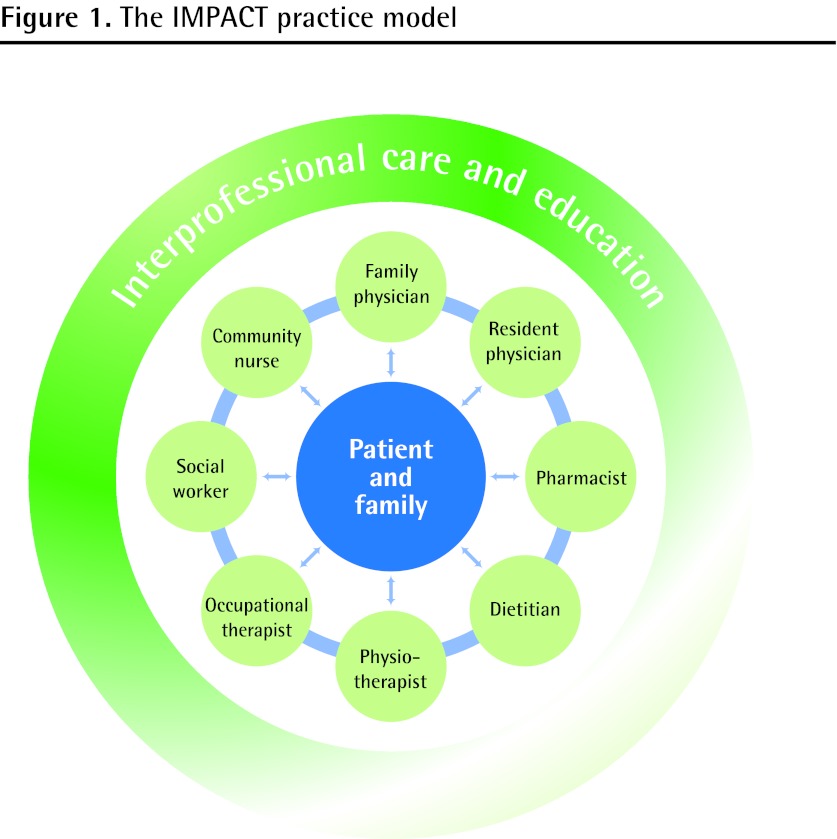

The IMPACT clinic is an innovative new model of interprofessional primary care for elderly patients with complex health care needs. The comprehensive team comprises family physicians, a community nurse, a pharmacist, a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist, a dietitian, and a community social worker. The model is designed to accommodate trainees from each discipline. Patient appointments are 1.5 to 2 hours in length, during which time a diverse range of medical, functional, and psychosocial issues are investigated by the full interprofessional team.

Conclusion

The IMPACT model is congruent with ongoing policy initiatives in primary care reform and enhanced community-based care for seniors. The clinic has been pilot-tested in 1 family practice unit and modeled at 3 other sites with positive feedback from patients and families, clinicians, and trainees. Evaluation data indicate that interprofessional primary care models hold great promise for the growing challenge of managing complex chronic disease.

Résumé

Problème à l’étude

Le nombre croissant de patients âgés qui présentent plusieurs conditions chroniques constitue un problème urgent en contexte de soins primaires. Les modèles de pratique actuels ne sont pas en mesure de répondre aux besoins de soins complexes de cette clientèle.

Objectif du programme

La clinique IMPACT (Interprofessional Model of Practice for Aging and Complex Treatments) avait pour objectif principal de créer et d’évaluer un nouveau modèle de soins pour personnes âgées vivant dans le milieu naturel qui requièrent des soins de santé complexes. Un second objectif était de vérifier la possibilité que ce modèle puisse devenir une occasion de formation à la pratique interprofessionnelle.

Description du programme

La clinique IMPACT est un modèle innovateur de soins primaires interprofessionnels pour les patients âgés requérant des soins de santé complexes. L’équipe comprend des médecins de famille, une infirmière communautaire, un pharmacien, un physiothérapeute, un ergothérapeute, un diététiste et un travailleur social communautaire. Le modèle permet d’accueillir des stagiaires de chacune des disciplines. Les patients ont des rendezvous de 90 à 120 minutes, pendant lesquels divers problèmes d’ordre médical, fonctionnel et psychosocial sont investigués par l’ensemble de l’équipe.

Conclusion

Le modèle IMPACT est conforme aux nouvelles politiques découlant de la réforme des soins primaires et il améliore les soins des personnes âgées vivant dans la communauté. La clinique a fait l’objet d’une étude pilote dans une unité de pratique familiale pour ensuite être essayée dans 3 autres sites, avec des commentaires positifs de la part des patients, des familles et des stagiaires. Les résultats de l’évaluation indiquent que le modèle de soins primaires interprofessionnels constitue une réponse très intéressante au défi croissant que représente le traitement des maladies chroniques complexes.

Chronic disease is a matter of considerable and growing concern. According to recent estimates, 1 in 3 Canadian adults has a chronic condition.1 And, owing to increasing life expectancy and the aging of the baby boom generation, the number of Canadians living with chronic disease is expected to rise dramatically.2 The bulk of chronic disease management is provided in the primary care setting; however, most family physicians do not have sufficient time to address all issues in standard appointments and therefore rely on suboptimal management strategies that do not best serve the complex health needs of these patients. Studies have shown that chronic disease management according to clinical practice guidelines requires more time than is often available to family physicians.3

A further complicating factor is the increasing prevalence of multiple concurrent chronic diseases. In Canada, fully one-third of chronic disease cases are complex (ie, involve 2 or more coexisting chronic conditions). The treatment regimens for these patients tend to be complex4 and typically require considerable time and resources from health care providers, family caregivers, and the patients themselves.5,6 Contrary to popular belief, the elderly patient population tends to be more heterogeneous than any other with respect to health status and health care needs.7 There is growing recognition that clinical practice guidelines are severely limited in their applicability to this patient population: the evidence base is often weak, adjustment of treatment targets in light of multiple chronic diseases is seldom addressed, and there is often no discussion of the expected time to benefit.8–11

With a view to responding to these multiple challenges, the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences recently produced a report entitled Transforming Care for Canadians with Chronic Health Conditions.12 The consensus statement of the expert panel expresses a vision in which

all Canadians with chronic health conditions have access to healthcare that recognizes and treats them as people with specific needs; where their unique conditions and circumstances are known and accommodated by all of their healthcare providers; and where they are able to act as partners in their own care.12

Achieving this vision will require new and innovative models of care. There is growing interest in the potential of interprofessional team-based models of primary care service delivery.12–14 To date, however, few such models have been developed with a specific focus on older patients with complex health care needs. In 2008, Project IMPACT (Interprofessional Model of Practice for Aging and Complex Treatments) was initiated in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ont. The Family Practice Unit at Sunnybrook provides primary care services to a large and varied practice population with a high proportion of elderly patients.

Objective of the program

The primary objective of IMPACT was to design and evaluate a new interprofessional team-based model of care for community-dwelling seniors with complex health care needs. A secondary objective was to explore the potential of this new model as an interprofessional training environment, both for health care trainees and practising clinicians. This paper presents a clinical program description and therefore largely focuses on the first of these 2 objectives.

Program description

The IMPACT clinic was developed collaboratively by an interprofessional team of clinicians, educators, and researchers. Several strategic partnerships were established with local community-based health and social care agencies. The IMPACT practice model (Figure 1) comprises family physicians, a community nurse, a pharmacist, a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist, a dietitian, and a community social worker. In addition, the model is designed to accommodate trainees from each of the various disciplines.

Figure 1.

The IMPACT practice model

All members of the interprofessional team attended the weekly clinics, which were scheduled for the full day on Fridays. Each member assumed 3 unique roles in the project: 1) as clinician, providing clinical care for patients and families in the weekly interprofessional clinic; 2) as educator, providing information, guidance, and support both to new trainees and to practising clinicians; and 3) as innovator, contributing to the ongoing refinement and evaluation of the interprofessional practice model.

Patients were referred to the IMPACT clinic by their regular family physicians in the Family Practice Unit. The eligibility criteria were as follows: 65 years of age or older; 3 or more chronic diseases requiring monitoring and treatment (or 2 chronic diseases when 1 is frequently unstable); 5 or more long-term medications; a minimum of 1 functional limitation on activities of daily living; and not homebound or institutionalized.

Referred patients were provided in advance with a description of the IMPACT clinic and then invited to attend. Patients were encouraged to bring the following to their appointment: any family members or paid caregivers involved in their care; all of their current medications (both prescription and over-the-counter medications); and a list of their current concerns. Patients were scheduled for an extended appointment (1.5 to 2 hours), during which a diverse range of medical, functional, and psychosocial issues were investigated by the full team.

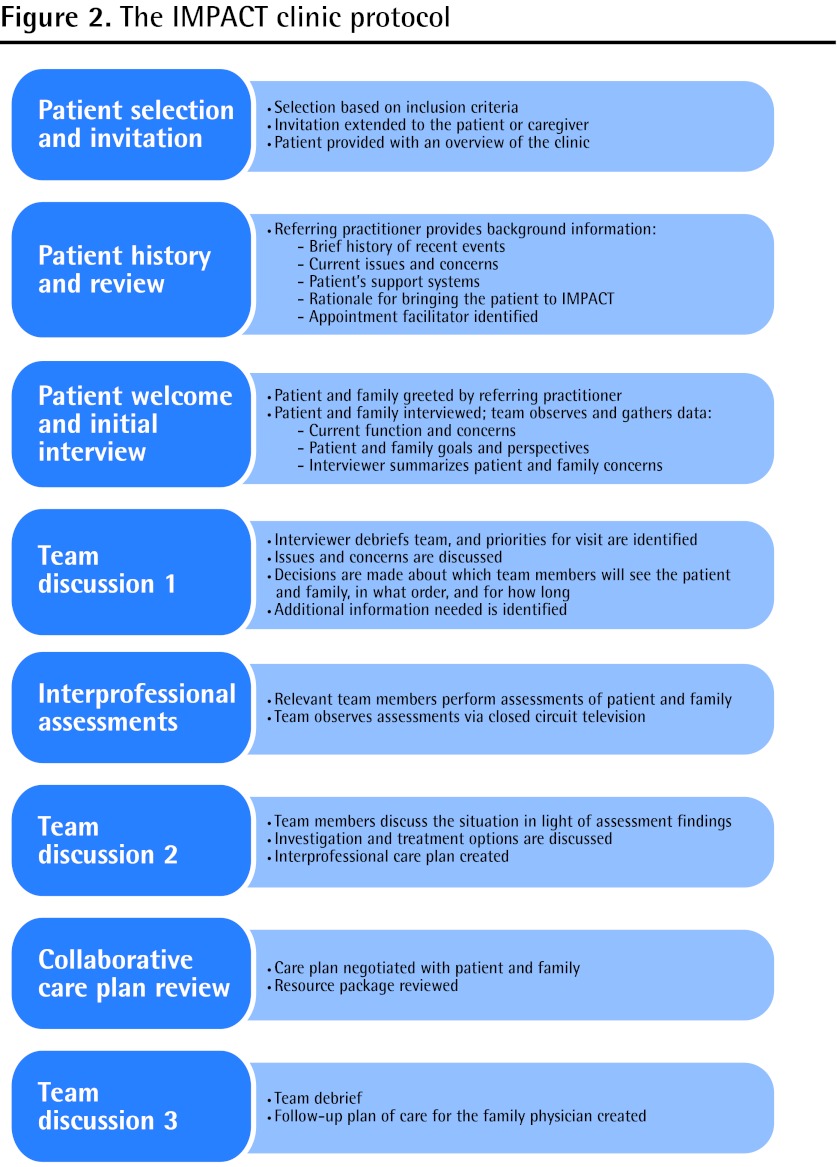

The IMPACT clinic protocol evolved over time through an ongoing process of interprofessional collaboration and teamwork (Figure 2). At the visit, the patient and family members were met by the family physician and a family medicine resident. After being introduced to the team, the patient and family were brought to an examination room, where the resident conducted a 20-minute quality-of-life interview that was designed to “unpack” the patient’s circumstances and concerns. This initial interview, which did not involve any physical examinations, was observed by the full team via closed-circuit television. This model allows for real-time information sharing and collaboration among all members of the team. Upon completion of the initial interview, the resident returned to the team for debriefing and discussion.

Figure 2.

The IMPACT clinic protocol

During each visit, there were 3 formal discussion periods in which the full team assembled to identify patient- and family-centred priorities, to share assessments and insights, and to develop collaborative strategies for care management. At the outset, a facilitator was appointed from within the team to ensure that the clinic remained on track and ran smoothly. Informal discussion in smaller groups occurred routinely throughout the visit. During the first formal discussion period, patient and family priorities and team concerns were discussed and clarified in order to plan the sequence of clinical assessments to follow.

Once the visit plan was in place, members of the team met with the patient and conducted interprofessional assessments. The assessments were typically led by 1 member of the team with participation from 1 or 2 other members, as appropriate, while the rest of the team observed via closed-circuit television. Knowledge and perspectives were continuously being shared among team members and were often incorporated into the assessment of another practitioner from a different discipline. When the assessments had been completed, the team reassembled for the second formal discussion period in order to draft the interprofessional care plan.

Drawing from the interprofessional care plan, a patient-friendly “to-do list” was created for the patient and family to take home. This formed part of the IMPACT information package, which included a complete and up-to-date medication list and other relevant educational information and resources. Any necessary referrals and follow-up appointments were arranged, and these details were included in the information package.

Next, the care plan was finalized in collaboration with the patient and family. The family physician and resident returned to the patient and family to review the care plan with them, as well as the medication list and any other resource materials being provided. The patient and family were encouraged to raise concerns, ask questions, and discuss the specifics of the care plan with the family physician and resident.

At the end of the visit, the team came together for a final debriefing and discussion. During this time, a follow-up plan of care was developed for the family physician, who would resume ongoing care of the patient. The follow-up plan included a list of the issues identified and addressed at the IMPACT visit, as well as any outstanding concerns and a proposed management plan for these concerns that the family physician could refer to at the patient’s next regular family practice appointment.

Evaluation

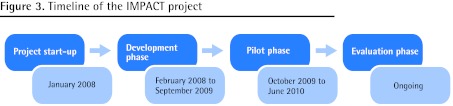

The IMPACT clinic operated from February 2008 to June 2010 (Figure 3). In total, there were 188 patient visits by 120 unique patients. Sixty family medicine residents rotated through the IMPACT clinic, with each resident participating in an average of 3 clinics. Trainees from each of the other disciplines also rotated through the clinic. The initial development phase of the project (February 2008 to September 2009) was followed by a 9-month pilot-test phase. Those patients who attended the clinic between October 2009 and June 2010 were included in the evaluation (N = 42), and a comprehensive chart review was performed for each of these patients.

Figure 3.

Timeline of the IMPACT project

Patients seen during the pilot phase had a mean age of 83.90 years; there were more women than men (Table 1). The complexity of the patients in this sample is evidenced by the mean numbers of chronic conditions and current medications. To capture this clinical complexity, we are investigating the utility of a “complexity score,” which is simply the sum of the number of chronic conditions and the number of medications for a given patient.15 For these 42 patients, the mean (SD) complexity score was 19.74 (5.56). Pilot-phase patients and their families presented to the IMPACT clinic with a mean of 5.52 concerns. By contrast, upon assessment, 8.50 concerns were identified by the IMPACT team. On average, patients were seen by 5.76 health care professionals during their visit to the IMPACT clinic.

Table 1.

Profile of IMPACT patients seen during pilot phase: N = 42.

| CHARACTERISTIC | MALE PATIENTS (N = 12) | FEMALE PATIENTS (N = 30) | ALL PATIENTS (N = 42) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, y | 83.33 (6.65) | 84.13 (7.67) | 83.90 (7.32) |

| Mean (SD) no. of chronic conditions | 8.08 (3.75) | 9.07 (2.98) | 8.79 (3.20) |

| Mean (SD) no. of medications | 11.50 (2.71) | 10.73 (4.27) | 10.95 (3.88) |

| Mean (SD) complexity score | 19.58 (5.14) | 19.80 (5.80) | 19.74 (5.56) |

| Mean (SD) no. of patient or family concerns identified | 4.92 (1.93) | 5.77 (2.64) | 5.52 (2.46) |

| Mean (SD) no. of team concerns identified | 9.33 (3.73) | 8.17 (2.76) | 8.50 (3.06) |

| Mean (SD) no. of IMPACT clinicians seen | 6.17 (1.27) | 5.60 (1.28) | 5.76 (1.28) |

IMPACT—Interprofessional Model of Practice for Aging and Complex Treatments.

Table 2 presents data about the specific issues identified and the corresponding interventions. A mean of 10.50 issues were identified per patient, with 10.48 corresponding interventions. The most common issues related to medications (mean 2.88), mobility (mean 2.43), and nutrition (mean 1.71). Of interest, male patients had substantially more issues with home safety than females did. Interventions in the domains of medications, mobility, and nutrition were most common as well. Issues and interventions in cognition, social interaction, home safety, sensory capability, and nursing were identified with slightly less frequency. On average, patients received 1.05 referrals to other health care providers; the most frequent referrals were for home safety assessments and fall prevention.

Table 2.

Issues identified and interventions by IMPACT team

| ISSUE OR INTERVENTION | MALE PATIENTS (N = 12) | FEMALE PATIENTS (N = 30) | ALL PATIENTS (N = 42) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) no. of issues identified per patient | 12.08 (3.48) | 9.87 (3.74) | 10.50 (3.76) |

| • Medication issues | 3.50 (2.84) | 2.63 (1.87) | 2.88 (2.19) |

| • Mobility issues | 2.25 (1.60) | 2.50 (1.38) | 2.43 (1.43) |

| • Nutrition issues | 1.75 (0.75) | 1.70 (1.02) | 1.71 (0.94) |

| • Cognition issues | 1.42 (1.00) | 1.00 (0.87) | 1.12 (0.92) |

| • Social issues | 0.92 (0.79) | 0.87 (0.90) | 0.88 (0.86) |

| • Home safety issues | 1.33 (1.15) | 0.57 (0.94) | 0.79 (1.05) |

| • Sensory issues | 0.50 (0.80) | 0.43 (0.57) | 0.45 (0.63) |

| • Nursing issues | 0.42 (0.51) | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.24 (0.43) |

| Mean (SD) no. of interventions per patient | 12.67 (3.96) | 9.60 (3.63) | 10.48 (3.93) |

| • Medication interventions | 4.92 (2.87) | 4.10 (2.16) | 4.33 (2.38) |

| • Nutrition interventions | 2.00 (0.74) | 1.63 (0.93) | 1.74 (0.89) |

| • Mobility interventions | 1.58 (1.16) | 1.60 (1.13) | 1.60 (1.13) |

| • Social work interventions | 1.92 (1.56) | 1.10 (1.30) | 1.33 (1.41) |

| • Home safety interventions | 1.25 (1.06) | 0.60 (1.00) | 0.79 (1.05) |

| • Nursing interventions | 0.58 (0.90) | 0.23 (0.57) | 0.33 (0.69) |

| • Cognition interventions | 0.25 (0.45) | 0.23 (0.50) | 0.24 (0.48) |

| • Sensory interventions | 0.17 (0.58) | 0.10 (0.31) | 0.12 (0.40) |

IMPACT—Interprofessional Model of Practice for Aging and Complex Treatments.

Interprofessional practice models demand a high level of team function. To assess the function of the IMPACT team, all members of the team completed a validated 56-item measure of teamwork in health care settings. The survey was completed twice, with a 2-year interval. The IMPACT team scored extremely high across the 2 tests; scores on all 7 dimensions of team function were above those of a reference group consisting of 55 family health teams (FHT) from across Ontario.

To investigate the portability of the IMPACT model, the clinic was peer-modeled at 3 FHT sites in the greater Toronto area. For each of the sites, the IMPACT team visited and modeled the protocol with 1 of the FHT’s regular patients. According to the evaluation surveys that were completed at the FHT sites (N = 32), participants planned to change how they managed elderly patients with complex chronic disease and how they collaborated with colleagues on their clinical teams.

Taken together, the evaluation data indicate that the IMPACT model is feasible, effective, well received, and portable. The cost-effectiveness of the IMPACT model has not yet been established. Further evaluation, including a pragmatic clinical trial, is currently under way.

Discussion

The IMPACT clinic is an innovative new model of interprofessional primary care for elderly patients with complex health care needs. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports of similar team models in family medicine. Our experience demonstrates the importance and value of an interprofessional approach in the identification and management of complex health-related concerns in the primary care setting, where the prevalence of elderly patients with complex needs is relatively high and increasing.16,17

Patients seen in the IMPACT clinic were typically making frequent visits to their regular family physicians, in addition to numerous other visits for diagnostic tests, laboratory work, and specialist referrals. The traditional 15-minute family practice visit was not well suited to this patient population, and it was becoming increasingly clear that a new model of care was needed. Patients, families, and health care professionals have reported that the IMPACT model has numerous advantages. For patients and families, the extended interprofessional visit allows sufficient time and “space” for patients and family members to raise and discuss multiple problems with a team of professionals; indeed, a number of patients reported that the new model allowed them to “tell their story” and to “be heard.” Because family caregivers of elderly patients often encounter considerable scheduling challenges as a result of multiple visits, the “one-stop shop” approach of IMPACT was much preferable to the status quo of multiple visits to multiple providers over an extended period of time.

We recognize that the IMPACT practice model is not without its own limitations. The extended visits that are required by the IMPACT model are not easily tolerated by extremely frail patients or those patients with pronounced sensory deficits or mental health conditions. Likewise, morning appointments are not ideal for some elderly patients, which can make clinic scheduling a challenge if that is when the team is available. It became clear to the team that some elderly patients lacked the capacity or the support to implement the types of changes that were being recommended, which speaks to the pressing need for enhanced community-based support programs for seniors living at home in the community. At the institutional level, the IMPACT model requires a substantial investment of resources in order to build the interprofessional team, and not all practice funding models will easily accommodate such expenditures. In addition, once the team is in place, staff scheduling can prove an issue owing simply to the number of individual professionals involved in this type of team-based practice model.

In spite of the financial and scheduling challenges just noted, the single most important feature of the IMPACT practice model is that it brings together a comprehensive interprofessional team of health care professionals who practise and learn together in a real-time, shared-clinic environment. In this way, the IMPACT model creates an opportunity for genuine interprofessional care and education; in our experience, the level of understanding and respect for differing discipline-based approaches was considerably enhanced over time. Indeed, through the course of the development and pilot testing of the IMPACT clinic, discipline-specific assessments and treatment plans evolved to become truly interprofessional. The presence of a multiplicity of health professions emerged as a distinct benefit of the model on account of the reduced need for serial referrals and multiple consultations. Participating family physicians have reported that, for those patients assessed in the IMPACT clinic, subsequent primary care visits were more tractable and efficient because the most pertinent issues had been identified and a comprehensive patient-centred care plan had been developed and implemented.

The IMPACT model was specifically designed to address many of the greatest challenges facing health care in Canada. These challenges include the aging of the population, the growing epidemic of chronic disease, the shortage of family physicians, and the fragmentation of health care service delivery. These challenges are well known to health care policy makers, and a variety of current policy initiatives are directed at promoting innovation and reform across the primary care and community care sectors. For instance, the FHT program in Ontario emphasizes interprofessional teamwork, requires extended after-hours care, and specifically focuses on chronic disease management, disease prevention, and health promotion. Between 2005 and 2010, a total of 200 FHTs were implemented across the province.18 Likewise, there are policy initiatives directed toward increasing spending and resources in the community care sector. For example, the Aging at Home Strategy aims to ensure that Ontario seniors have access to comprehensive community-based health care in the comfort and dignity of their own homes. The stated objective is to assist seniors in leading healthy and independent lives while avoiding unnecessary visits to hospitals, which can ultimately reduce inpatient bed pressures as well as emergency department wait times.19 These 2 specific initiatives, as with other programs across the country, are serving to reshape the health care policy environment, and in so doing they considerably enhance the feasibility and sustainability of projects like the IMPACT clinic. Thus, while there remain substantial challenges in implementing health care reform, current real-world policy shifts are enabling and incentivizing the type of innovative change that is urgently required.

Conclusion

There is a pressing need for innovative approaches to the care of seniors, particularly those with multiple chronic conditions. These new models are most urgently required in primary care; therefore, the models should be developed and evaluated in that setting. The IMPACT clinic was pilot-tested in 1 family practice unit and modeled at 3 other sites with positive feedback from and outcomes for patients and families, health care trainees, and clinicians alike. Our experience indicates that interprofessional primary care models hold great promise for the growing challenge of complex chronic disease. Recruitment is currently under way for a multisite trial to evaluate the feasibility, effectiveness, and sustainability (cost-effectiveness) of the IMPACT practice model. Policy initiatives and research programs directed toward primary care reform are driving innovation and should be continued and, indeed, expanded.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the IMPACT team for their contributions to the project. A great debt of gratitude is owed to our IMPACT patients and families, without whom this project could not have happened and from whom a great deal was learned. Funding for the IMPACT project was provided by HealthForceOntario (a joint initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities).

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The bulk of chronic disease management is provided in the primary care setting; however, most family physicians do not have sufficient time to address all the necessary issues in standard appointments and therefore rely on suboptimal management strategies that do not best serve the complex health needs of patients with chronic disease.

The IMPACT clinic is an interprofessional team-based model of care for community-dwelling seniors with complex health care needs. All members of the interprofessional team participated in patient assessments and worked together to develop an individualized, patient-friendly care plan, as well as a follow-up plan for the family physician who would resume patient care after the IMPACT assessment.

The pilot evaluation data indicate that the IMPACT model is feasible, effective, well received, and portable. The IMPACT practice model brings together a comprehensive interprofessional team of health care professionals who practise and learn together in a real-time, shared-clinic environment, creating an opportunity for genuine interprofessional care and education.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

C’est dans les établissements de soins primaires que sont traitées la majeure partie des maladies chroniques; toutefois, la plupart des médecins de famille n’ont pas suffisamment de temps pour s’occuper de tous les problèmes lors d’un rendezvous habituel, si bien qu’ils doivent recourir à des stratégies de traitement qui ne répondent pas de façon idéale aux besoins de santé complexes des patients souffrant de maladies chroniques.

La clinique IMPACT est un modèle de soins interprofessionnel en équipe à l’intention de personnes âgées vivant dans la communauté qui requièrent des soins de santé complexes. Tous les membres de l’équipe interprofessionnelle participaient à l’évaluation des patients et à l’élaboration d’un plan de soins individuels adapté au patient, mais aussi à un plan pour le médecin de famille qui assurera le suivi après l’évaluation de l’IMPACT.

Les données de l’évaluation pilote indiquent que le modèle IMPACT est faisable, efficace, bien reçu et mobilisable. Le modèle IMPACT réunit une importante équipe de professionnels de la santé qui pratiquent et apprennent dans un contexte de temps réel et de partage d’une clinique, créant ainsi un climat favorisant des soins et une formation interprofessionnels.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Competing interests

None declared

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conception, design, and implementation of the program and to the evaluation of its effectiveness. Mr Tracy conducted the data analysis, drafted the first version of the manuscript, and contributed to subsequent revisions. Ms Bell participated in the data analysis and contributed to the drafting and revising of the manuscript. Drs Nickell, Charles, and Upshur contributed to the interpretation of data and to the revising of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Health Council of Canada . Why health care renewal matters: learning from Canadians with chronic health conditions. Toronto, ON: Health Council of Canada; 2007. Available from: www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/rpt_det.php?id=142. Accessed 2013 Jan 13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton FT, Spencer BG. Chronic health conditions: changing prevalence in an aging population and some implications for the delivery of health care services. Can J Aging. 2010;29(1):11–21. doi: 10.1017/S0714980809990390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Østbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajcar JM, Wang L, Moineddin R, Nie JX, Tracy CS, Upshur RE. From pharmaco-therapy to pharmaco-prevention: trends in prescribing to older adults in Ontario, Canada, 1997–2006. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upshur REG, Tracy S. Chronicity and complexity. Is what’s good for the diseases always good for the patients? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1655–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moineddin R, Nie JX, Wang L, Tracy CS, Upshur RE. Measuring change in health status of the elderly at the population level: the transition probability model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:306. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of specific disease guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2870–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutasingwa DR, Ge H, Upshur RE. How applicable are clinical practice guidelines to elderly patients with comorbidities? Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e253–62. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/57/7/e253.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2013 Jan 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upshur REG. Can family physicians practise good medicine without following clinical practice guidelines? Yes [Debate] Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:518, 520. (Eng), 522, 524 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortin M, Contant E, Savard C, Hudon C, Poitras ME, Almirall J. Canadian guidelines for clinical practice: an analysis of their quality and relevance to the care of adults with comorbidity. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Academy of Health Sciences . Transforming care for Canadians with chronic health conditions. Report of the Expert Panel. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2010. Available from: www.cahs-acss.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/cdm-final-English.pdf. Accessed 2013 Jan 13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oandasan IF. The way we do things around here. Advancing an interprofessional care culture within primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:1173–4. (Eng), e60–2 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman J, Meuser J, Rogers J, Lawrie L, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration in family health teams. An Ontario-based study. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e368–74. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/56/10/e368.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2013 Jan 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upshur REG, Wang L, Moineddin R, Nie J, Tracy CS. The complexity score: towards a clinically-relevant, clinician-friendly measure of patient multi-morbidity. Int J Pers Cent Med. 2012;2(4):799–804. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell SH, Tracy CS, Upshur REG, IMPACT Team The assessment and treatment of a complex geriatric patient by an interprofessional primary care team. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Mar 15; doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smirnova A, Bell SH, Tracy CS, Upshur REG, IMPACT team Still dizzy after all these years: a 90-year-old woman with a 54-year history of dizziness. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Sep 13; doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . Family health teams. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2011. Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/fht. Accessed 2013 Jan 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . Aging at home strategy. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2011. Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/program/ltc/33_ontario_strategy.html. Accessed 2013 Jan 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]