Abstract

In heroin-dependent individuals, the drive to avoid or ameliorate the negative affective/emotional state associated with the discontinuation of heroin contributes to the chronic relapsing nature of the disease. Here, we investigate changes in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) expression at three time points across an extended period of heroin withdrawal in a clinically relevant rodent model of addiction using conditioned place aversion (CPA) in POMC-EGFP bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice. Neurons expressing POMC-EGFP were found in the medial nucleus of amygdala (MeA), basomedial amygdala (BMA) and dentate gyrus of hippocampus (DG), as well as the arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus (ARC). Heroin-treated mice displayed robust CPA after acute spontaneous withdrawal (12h), which persisted across the extended (14d) withdrawal period. After 12h withdrawal, heroin-treated mice showed lower signal intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells in the ARC, higher levels of POMC mRNA in the amygdala but lower levels in the hippocampus than saline controls. After 7d withdrawal, heroin-treated mice showed fewer POMC-EGFP positive cells in the MeA and lower POMC mRNA in the amygdala than saline controls. After extended (14d) withdrawal, heroin-treated mice showed more POMC-EGFP positive cells in BMA and DG, increased intensity of POMC-EGFP signal in DG, and higher POMC mRNA levels in hippocampus compared to controls. Our results show dynamic changes in POMC in hypothalamic and extra-hypothalamic regions that may contribute to the negative affective/emotional state of heroin withdrawal shown by CPA from acute to extended periods of heroin withdrawal.

Keywords: Amygdala, Bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice, Conditioned place aversion, Heroin withdrawal, Hippocampus, Proopiomelanocortin

1. Introduction

Heroin addiction is a chronically relapsing disorder characterized by persistent and/or compulsive drug seeking and consumption, loss of control in limiting consumption, and emergence of aversive emotional and physiological states (e.g., dysphoria, anxiety, sympathetic hyperactivation) when drug exposure is discontinued (i.e., during withdrawal). The drive to avoid or ameliorate this negative emotional state is thought to contribute to the chronic relapsing nature of the disease and its clinical morbidity. To assess the aversive emotional state in withdrawal, we use the conditioned place aversion (CPA) paradigm, which has been used to study aversive motivational consequences of withdrawal from a chronic state of opioid dependence (e.g., Spanagel et al., 1994, Rothwell et al., 2009).

Like humans, rodents allowed to self-administer heroin with extended access (6–18 hours) (Ahmed et al., 2000, Shalev et al., 2001, Kruzich et al., 2003, Chen et al., 2006, Picetti et al., 2012) and/or escalating doses (Dai et al., 1989, Kruzich et al., 2003, Picetti et al., 2012) will increase their drug consumption over time. Since long-term molecular consequences of drug addiction and withdrawal from drug dependence cannot be systematically studied in humans, by taking advantage of a clinically relevant model of drug addiction, it is possible to reveal key neurobiological factors that contribute to the withdrawal state from drug dependence. Therefore, in this study, we used the clinically relevant mouse model which an escalating-dose paradigm of chronic heroin exposure following prolonged withdrawal, designed to mimic the self-administration patterns and drug history seen in human addicts (e.g., Dole et al., 1966, Kreek et al., 2009).

Heroin and other short-acting mu-opioid receptor (MOP-r) agonists have been shown to alter the activity of endogenous opioid systems. In humans, chronic exposure to such MOP-r agonists causes a relative deficiency in the beta-endorphin/MOP-r system (see review in Kreek, 1996). One study reported decreased beta-endorphin-immunoreactivity in several brain regions following chronic (7-day) morphine treatment by pellets (total of 6 pellets each containing 75 mg morphine; 1 pellet on the 1st day, 2 pellets on the 3rd day and 3 pellets on the 5th day), and in acute (16-hour) withdrawal after removal of the morphine pellets in Sprague-Dawley rats (Gudehithlu et al., 1991). Also, detected by cDNA hybridization, decreased levels of the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) gene, which encodes the precursor of the major endogenous opioid peptides beta-endorphin with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), has been found in the hypothalamus after chronic (7-day) morphine treatment by pellets (total of 4 pellets each containing 75 mg morphine; 1 pellet on the 1st day and 3 additional pellets on the 4th day) in Sprague-Dawley rats (Bronstein et al., 1990). However, changes in the beta-endorphin/MOP-r system in extended withdrawal from heroin dependence have not been elucidated. By identifying changes in the beta-endorphin/MOP-r system in the brain from acute to extended withdrawal periods in a clinically relevant model of heroin dependence, we may develop a better understanding of possible mechanisms underlying the efficacy of methadone and buprenorphine-naloxone treatment.

While expression of the POMC gene is primarily restricted to the arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus (ARC) and nucleus of the solitary tract (NST), our laboratory and others have detected low levels of POMC mRNA in extra-hypothalamic regions including the amygdala, cerebral cortex, nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, and striatum (Civelli et al., 1982, Zhou et al., 1996, Grauerholz et al., 1998). Recently, the advent of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic mice that use EGFP reporter genes have provided us with an anatomical map showing that POMC-EGFP positive neurons are found in mesocorticolimbic regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, ventral striatum, and caudate-putamen, (www.gensat.org) (developed in the NINDS GENSAT project) (Gong et al., 2003, Pinto et al., 2004), in parallel to the expression patterns mentioned above. Also, in the POMC-EGFP transgenic mouse, immunohistochemistry against POMC demonstrated >99% coexpression with POMC-EGFP-expressing neurons in the ARC (Pinto et al., 2004). Although these regions have been linked to behavioral and physiological responses to opiate withdrawal (Eisch et al., 2000, Rizos et al., 2005, Glass et al., 2008), because POMC expression levels tend to be low in extra-hypothalamic regions, limited work has explored the expression and/or function of POMC in these regions in relation to opiate withdrawal.

Therefore, in the present study, using a clinically relevant pattern of heroin exposure and extended withdrawal, we investigated POMC gene expression in hypothalamic and extra-hypothalamic regions linked with heroin withdrawal-induced aversive behavior in POMC-EGFP BAC transgenic mice.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

POMC-EGFP BAC transgenic mice, originally generated in Dr. J.M. Friedman’s laboratory at The Rockefeller University (New York, NY) were made by homologous recombination of a POMC gene-containing BAC comprising an EGFP insert, in which the POMC promoter drives EGFP expression (Gong et al., 2003, Pinto et al., 2004), maintained on a C57BL/6J background. Male POMC-EGFP positive mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) where the mutation had been backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for a minimum of 10 generations. Mice obtained from the Jackson Laboratory were then backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for an additional three generations in the Rockefeller University’s animal facility. POMC-EGFP positive and negative mice were identified by PCR analysis of DNA obtained from tail snips. POMC-EGFP negative mice were used as a control group to identify possible influences of the EGFP transgene on behavior and molecular endpoints. Male POMC-EGFP positive and negative mice (2–3 months) were housed in a stress-minimized animal facility, accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, at The Rockefeller University. Experimental animals were housed individually in standard clear cages with bedding, nest material and food/water ad libitum, and were weighed and handled daily (at 11:00). Animals were acclimated to a reverse 12:12 hour light/dark cycle (lights off from 07:00–19:00) for >1 week before the study; dim red lights allowed for observation.

2.2. Drug treatment

Heroin (diacetylmorphine HCl, obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse) was dissolved in physiological saline each day prior to injection. The schedule of heroin administration was designed to mimic patterns of heroin use often observed in human addicts with continued, intermittent administration of doses of heroin across the active period and into the inactive period of the circadian cycle, with escalating dose across for 14 days (Fig 2A). The regimen of chronic drug exposure (saline or heroin) consisted of intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections in the home cage three times daily with two 6-h intervals and one 12-h interval, beginning 4 hours after the beginning of the dark cycle and occurring every six hours thereafter (at 11:00, 17:00, and 23:00) for 14 days, as previously reported in rats (Seip et al., 2012). Each group started with 6 mice, and all completed the experiments.

Figure 2.

(A) Schedule of exposure to escalating doses of heroin, timing of the conditioning sessions during withdrawal state and timing of the post-test session in different groups. (B and C) Heroin withdrawal-induced Conditioned Place Aversion (CPA) after chronic intermittent escalating-dose heroin. Negative scores [downward bars] indicate an avoidance of the conditioned environment, due to its pairing with the aversive heroin withdrawal state. Both POMC-EGFP positive (B) and negative (C) mice showed strong CPA on acute spontaneous withdrawal (12 hours after receiving their final injection of chronic escalating dose of heroin). This CPA persists into extended spontaneous withdrawal (14 days after receiving their final injection of chronic escalating-dose of heroin). (D and E) Body weight loss induced by chronic escalating dose of heroin. Body weight changes (caluculated as percentage of baseline) displayed by POMC-EGFP positive (D) and negative (E) mice during received escalating-dose of heroin or saline and its withdrawal. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=6/group). ***p<0.001, *p<0.05 vs matched saline control group.

2.3. Heroin withdrawal-induced Conditioned Place Aversion (CPA)

2.3.1. Apparatus

The aversive state associated with heroin withdrawal was measured using a modified CPA procedure (Contarino and Papaleo, 2005). The CPA apparatus consisted of dimly lit, sound-attenuated chambers (model ENV-3013, MED Associates, St. Albans, VT) with three distinct compartments (white, gray and black) that could be separated by manually operated doors.

2.3.2. Pre-conditioning exposure

Prior to any injection, each mouse was placed in the central gray compartment with free access to the black and white compartments and time spent in each compartment was recorded for 30 min. The CPA was conducted using unbiased procedure, that is each mouse was assigned to a particular compartment for later heroin withdrawal conditioning, in a counter balance way, regardless of the initial preference for either compartment in the pre-conditioning exposure. Then, separate subsets of POMC-EGFP BAC positive and negative transgenic mice were exposed chronically to heroin or saline, as described above, for 14 days.

2.3.3. Conditioning

Each mouse was placed into either the black or white compartment of the apparatus (hereafter referred to as the “conditioning chamber”) for 30 min, 12 hours after the heroin injection (11:00) of the previous day. This 30 min conditioning session was repeated on the subsequent four days (Days 11–14) for a total of four conditioning sessions.

Post-conditioning test

The expression of CPA was tested in three separate groups of POMC-EGFP positive and negative mice after 12 hours, 7 days, or 14 days of withdrawal from the final injection of chronic heroin exposure. During the test session, each mouse was again placed in the central gray compartment with free access to the black and white compartments and time spent in each compartment was recorded for 30 min. The difference in time spent in the chamber associated with heroin withdrawal during the pre- and post-conditioning sessions was used to identify a withdrawal-induced CPA.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

In order to study neurobiological changes in parallel with the behavioral changes, mice were humanely sacrificed at three time points: 12 hours, 7 days, or 14 days after the final injection of chronic intermittent escalating-dose heroin administration following the post-conditioning session. Animals were sacrificed immediately following the post-conditioning session by decapitation following brief CO2 exposure (<20 s), their brains rapidly removed, and immediately placed into the fixation solution of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h at 4 °C. Then, the brains were equilibrated in PBS containing 10% sucrose for 4 h and then 30% sucrose for 48 h at 4 °C. As previously described (Niikura et al., 2008), brains were frozen, sectioned in 20 um slices and stored at −20°C in a solution containing 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 30% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.1 M PBS until they were used. For each animal, anatomically matched midbrain sections that included the arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus were defined and selected with reference to a mouse brain atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). Floating sections from POMC-EGFP positive mice were washed three times in 0.01 M PBS and then incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. After three washes in the PBS, the sections were blocked with 0.01 M PBS containing 3% normal donkey serum and 0.5% Triton X-100. Floating sections were then incubated in a goat polyclonal anti-EGFP primary antibody (1:200, Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA) for 24 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. The sections were further incubated with an Alexa488-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (1:500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in PBS for 90 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. Sections were then mounted onto Superfrost/Plus glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), air-dried and coverslipped with Fluoro-Gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). The images of immunostained sections were collected using the universal fluorescence microscope (Axiophot 2) (Carl Zeiss) at the Bio-Imaging Resource Center of The Rockefeller University.

2.4. Image analysis

Numbers of POMC-EGFP-positive neurons were counted in each brain region at 120 um intervals in consecutive sections. Brain regions were identified by anatomical landmarks defined by the mouse brain atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). Only cell nuclei with clear immunostaining were counted in the 4–5 sections of each brain region: arcuate hypothalamus (bregma from −1.46mm to −1.94), basomedial amygdala (bregma from −1.22 to −1.58), medial nucleus of amygdala (bregma from −1.34 to −1.70), dentate gyrus of hippocampus (from −1.34 to −1.70). The label intensity of positively labeled cells was also quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Briefly, the background intensity was measured using the ImageJ from non-stained parts of the same image and subtracted from the intensity of positive cells. The total intensity of each brain region obtained from heroin-treated mice was compared with the total intensity of mice treated with saline.

2.5. RNA preparation and quantitative analysis by real-time PCR

POMC-EGFP negative mice were sacrificed immediately following the testing session by decapitation followed by brief CO2 exposure (<20 s), as previously described (Schlussman et al., 2011). Their brains were rapidly removed, and slices were cut with a rodent brain matrix (ASI Instruments, Warren, MI). The hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus were dissected and RNA was isolated from their homogenates using the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion [ABI], Austin TX) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Following RNA isolation, all samples were treated with DNase (Turbo DNA-free™, Ambion [ABI], Austin, TX). The quantity and quality of RNA in each extract was determined with the NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). cDNA was synthesized from each sample using the Super Script™ III first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Five hundred ng of RNA extracted from the hypothalamus, amygdala or hippocampus were used for reverse transcription. Real time PCR analysis of the relative mRNA expression level of POMC was conducted using synthesized primers for POMC (forward: 5′-ATA GAT GTG TGG AGC TGG TG -3′, reverse: 5′-GGC TGT TCA TCT CCG TTG -3′) or GAPDH (forward: 5′ AAC TTT GGC ATT GTG GAA GG -3′, reverse: 5′-GGA TGC AGG GAT GAT GTT CT - 3′) and master mix (RT2qPCR™ primer assays and RT2 Real Time™ SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s directions in an ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (SDS2.3) (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA). Water controls for each primer set were included in every assay. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were calculated using SDS2.3 with an automatic baseline. All data were normalized to GAPDH and reported as 2−ΔΔCt where Ct is the threshold cycle for detecting fluorescence.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica (version 5.5), with a significance level of p<0.05. Student’s t-tests and analyses of variance (ANOVA) with independent and repeated measures followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test were used as appropriate for the experimental design. Development of CPA was analyzed by two-way ANOVA, Treatment × Withdrawal-time (time after the last injection). The change in the body weight was evaluated by two-way ANOVA (Treatment × Day) with repeated measures on the second factor. To examine the effect of genotype for the CPA and the change in the body weight, the data was examined by three-way ANOVA, Treatment × Genotype × Withdrawal-time (for CPA) or Treatment × Genotype × Day (for body weight). Total number of POMC-EGFP positive cells and intensity of immunoreactivity, and measurement of the POMC mRNA levels were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of POMC-EGFP fluorescence in the midbrain region

The distribution of POMC-EGFP fluorescence in the midbrain region, including the hippocampus, hypothalamus and amygdala in untreated mice, can be seen Fig. 1. This low magnification image shows the POMC-EGFP positive signal distribution in the hippocampus, hypothalamus and amygdala (example in Fig. 1A). For more detail, high magnification images show that POMC-EGFP fluorescence-positive cells exist in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus (DG) (Fig. 1B), the medial nucleus of amygdala (MeA), basomedial amygdala (BMA) (Fig. 1C), and arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus (ARC) (Fig. 1D). There is strong and bright fluorescence in the ARC. Although with a weaker signal, POMC-EGFP fluorescence-positive cells were also seen in the DG, the MeA and the BMA (arrows in B and C). Of interest, there are POMC-EGFP positive cells in submedius thalamic nucleus in the thalamus, not studied here.

Figure 1.

POMC-EGFP fluorescence in the midbrain region including the hippocampus, hypothalamus and amygdala (A). High magnification images show that POMC-EGFP fluorescence-expressing cells exist in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (DG) (B), the medial nucleus of the amygdala (MeA) and the basomedial amygdala (BMA) (C), and the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) (D). There is strong and bright fluorescence in the ARC. Although with a weaker signal, POMC-EGFP fluorescence-positive cells exist in the DG (arrows in B), MeA and BMA (arrows in C). Scale bar = 500 um (A), 50 um (B–D). 3V: third ventricular

3.2.1. Heroin withdrawal-induced conditioned place aversion (CPA)

The CPA of POMC-EGFP positive mice is shown in Fig. 2B. There was a significant main effect of Treatment [F(1,30)=51.25, p<0.001], of Withdrawal-time [F(2,30)=9.748, p<0.001] and a Treatment × Withdrawal-time interaction [F(2,30)=4.499, p<0.05] in the time spent in the withdrawal-paired compartment of the CPA apparatus by mice given chronic exposure to escalating-dose heroin or saline. The heroin-treated mice spent less time in the heroin withdrawal-paired chamber than did the saline-treated controls. Post-hoc tests revealed that the time spent in the heroin withdrawal -paired compartment differed from saline controls at all time points studied (12-hour, p<0.001; 7-day, p<0.05; 14-day, p<0.05). The CPA of POMC-EGFP negative mice is shown in Fig 2C: there was a significant main effect of Treatment [F(1,30)= 108.7, p<0.001], of Withdrawal-time [F(2,30)=6.319, p<0.001] and a Treatment × Withdrawal-time interaction [F(2,30)= 4.637, p<0.001] in the time spent in the withdrawal-paired compartment of the CPA apparatus by mice given chronic exposure to escalating-dose heroin or saline. These heroin-treated mice spent less time in the heroin withdrawal-paired chamber than did the saline-treated controls. These results are similar to those in POMC-EGFP positive mice. Three-way ANOVA revealed that there was no main effect of genotype. Thus, we find no evidence that the EGFP transgene affects heroin withdrawal-induced aversion.

3.2.2. Body weight

In order to confirm that mice were in withdrawal, loss of body weight was examined (Gellert and Holtzman, 1978, Langerman et al., 2001). In POMC-EGFP positive mice, body weight progressively decreased across the 14 days of chronic escalating-dose heroin administration [main day effect [F(19,200)= 26.03, P<0.001; main treatment effect: F(1,200)= 9.624, P<0.05; interaction: F(19,200)= 7.508; P<0.001] (Fig. 2D). Post hoc tests revealed that weights decreased significantly between day 8 and day 15 (P<0.05 to 0.001) compared with the day before injection (day 0), and were lower in the heroin-treated group than in saline treated controls (P<0.05 to 0.001). Two days after the last injection of heroin (day 16), body weights of the heroin group were at levels similar to control mice. A similar result was seen in POMC-EGFP negative mice (Fig. 2E). The body weight of POMC-EGFP negative mice that received chronic escalating-dose heroin decreased significantly [main day effect [F(19,200)= 24.77, P<0.001; main treatment effect: F(1,200)= 18.81, P<0.01; interaction: F(19,200)= 13.78; P<0. 001]. Post hoc tests revealed that weights decreased significantly between day 8 and day 15 (P<0.05 to 0.001) compared with the day before injection (day 0) and were lower in the heroin-treated group than its saline treated controls (P<0.001). This body weight loss in the heroin group was no longer seen two days after the last injection of heroin (day 16). Three-way ANOVA revealed that there was no main effect of EGFP status or its interactions. Thus, insertion of the EGFP construct into the POMC gene did not affect body weight changes during chronic escalating-dose heroin administration.

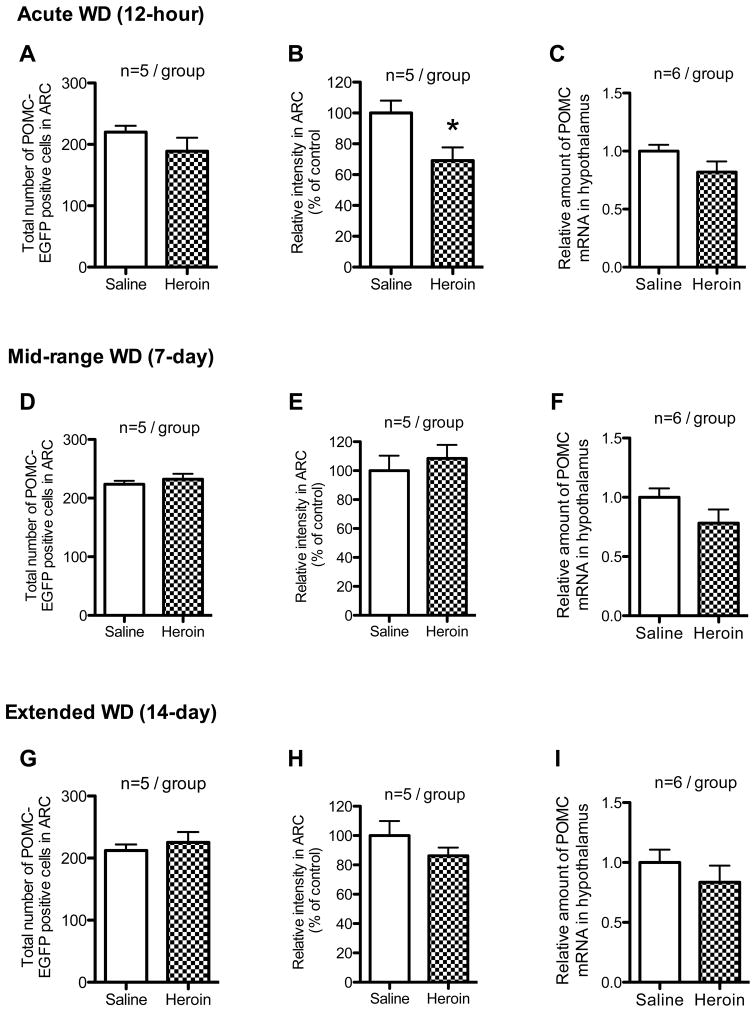

3.3. Effect on POMC-EGFP expression in hypothalamus of spontaneous withdrawal from escalating-dose heroin-induced CPA

3.3.1. Acute (12-hour) spontaneous withdrawal

The total number of the positive cells (Fig. 3A) and the level of POMC mRNA (Fig. 3C) in the heroin-treated group were similar to the saline-treated control. However, the total intensity of the positive cells was lower in the heroin-treated group than in its saline-treated control (Fig. 3B; t=2.63, df=8, p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Change in POMC-EGFP positive cells and POMC mRNA in the hypothalamus in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal (WD) from the last injection of chronic escalating doses of heroin administration. The total number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal are shown in A, D and G, respectively. The total relative intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in ARC in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal are shown in B, E and H, respectively. The level of POMC mRNA in the hypothalamus in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal in POMC-EGFP negative mice are shown in C, F and I, respectively. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 vs saline group.

3.3.2. Mid-range (7-day) spontaneous withdrawal

The total number (Fig. 3D) and intensity (Fig. 3E) of the positive cells and the level of POMC mRNA (Fig. 3F) in the heroin-treated group were similar to saline-treated controls.

3.3.3. Extended (14-day) spontaneous withdrawal

The total number (Fig. 3G), the intensity (Fig. 3H) of the positive cells and the level of POMC mRNA (Fig. 3I) in the heroin-treated group were similar to saline-treated controls.

3.4. Effect on POMC-EGFP expression in amygdala of spontaneous withdrawal from escalating-dose heroin-induced CPA

3.4.1. Acute (12-hour) spontaneous withdrawal

In the BMA, the total number of the positive cells was greater in the heroin-treated group than saline-treated controls (Fig. 4A; t=2.33, df=8, p<0.05). However, the total intensity of the positive cells in the heroin-treated group was similar to saline-treated controls (Fig. 4B). In the MeA, the total number (Fig. 4C) and total intensity (Fig. 4D) of positive cells in the heroin-treated group were similar to saline-treated controls. The levels of POMC mRNA in the whole amygdala were higher in the heroin-treated group than in saline-treated controls (Fig. 4E; t=2.52, df=10, p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Change in POMC-EGFP positive cells and POMC mRNA in the amygdala in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal from the last injection of chronic escalating doses of heroin administration. In acute spontaneous withdrawal, the total number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in the basomedial amygdala (BMA) and the medial nucleus of the amygdala (MeA) are shown in A and C, respectively. The total relative intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in BMA and MeA are shown in B and D, respectively. The level of POMC mRNA in POMC-EGFP negative mice in amygdala is shown in E. In mid-range spontaneous withdrawal, the total number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in BMA and MeA are shown in F and H, respectively. The total relative intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in BMA and MeA are shown in G and I, respectively. The level of POMC mRNA in POMC-EGFP negative mice in amygdala is shown in J. In extended spontaneous withdrawal, the total number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in BMA and MeA are shown in K and M, respectively. The total relative intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in BMA and MeA are shown in L and N, respectively. The level of POMC mRNA in POMC-EGFP negative mice in amygdala is shown in O. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 vs saline group.

3.4.2. Mid-range (7-day) spontaneous withdrawal

In the BMA, the total number (Fig. 4F) and intensity (Fig. 4G) of the positive cells in the heroin-treated group were similar to saline-treated controls. In the MeA, the total number of positive cells was lower in the heroin-treated group than in saline-treated controls (Fig. 4H; t=4.38, df=8, p<0.01). However, the total intensity of the positive cells in the heroin-treated group was similar to saline-treated controls (Fig. 4I). The levels of POMC mRNA in the whole amygdala were lower in the heroin-treated group than saline-treated controls (Fig. 4J; t=2.75, df=10, p<0.05).

3.4.3. Extended (14-day) spontaneous withdrawal

In the BMA, the total number of positive cells was greater in the heroin-treated group than in its saline-treated controls (Fig. 4K; t=3.11, df=8, p<0.05). However, the total intensity of the positive cells in the heroin-treated group was similar to saline-treated controls (Fig. 4L). In the MeA, the total number (Fig. 4M) and total intensity (Fig. 4N) of positive cells in the heroin-treated group were similar to saline-treated controls. Also, the levels of POMC mRNA in whole amygdala in the heroin- treated group were similar to saline-treated controls (Fig. 4O).

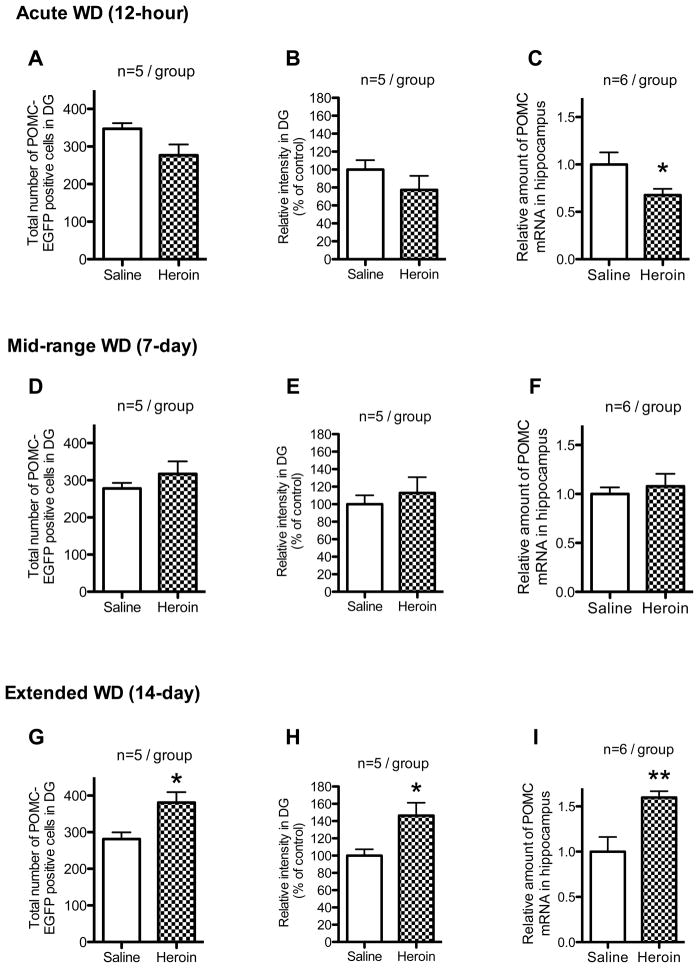

3.5. Effect on POMC-EGFP expression in hippocampus of spontaneous withdrawal from escalating-dose heroin-induced CPA

3.5.1. Acute (12-hour) spontaneous withdrawal

The total number of positive cells in the heroin-treated group was similar to saline-treated controls (Fig. 5A), but, there was a tendency toward a decreased total intensity of the positive cells in the heroin-treated group (Fig. 5B; t=2.16, df=8, p=0.0627). The levels of POMC mRNA were lower in the heroin-treated group than in saline-treated controls (Fig. 5C; t=2.25, df=10, p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Change in POMC-EGFP positive cells and POMC mRNA in the hippocampus in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal (WD) from the last injection of chronic escalating doses of heroin administration. The total number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in DG in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal are shown in A, D and G, respectively. The total relative intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells in POMC-EGFP positive mice in DG in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal are shown in B, E and H, respectively. The level of POMC mRNA in the hypothalamus in acute (12 hours), mid-range (7 days) or extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal in POMC-EGFP negative mice are shown in C, F and I, respectively. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 vs saline group.

3.5.2. Mid-range (7-day) spontaneous withdrawal

The total number (Fig. 5D) and intensity (Fig. 5E) of the positive cells, and the levels of POMC mRNA (Fig. 5F) in the heroin-treated group were similar to saline-treated controls.

3.5.3. Extended (14-day) spontaneous withdrawal

The total number (Fig. 5G) and intensity (Fig. 5H) of the positive cells in the heroin-treated group were higher than in saline-treated controls (t=2.95, df=8, p<0.05 and t=2.82, df=8, p<0.05, respectively). Also, the levels of POMC mRNA were higher in the heroin-treated group than saline-treated controls (Fig. 5I; t=3.42, df=10, p<0.01).

Since we conducted more than 30 t-tests, the statistical issue of multiple comparison should be considered. This is the first study of its kind and we would not like to miss any change of POMC expression at any time point or brain region studied, so we set the alpha level = 0.05. If the alpha level were set at 0.01, 2 tests are significant experiment-wise.

3.6. Examination of rostrocaudal sections of each brain region

This is the first study to explore that POMC expressions in MeA, BMA and DG as well as ARC. We counted the number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in the different rostrocaudal sections (“position”) in each brain region at three different withdrawal time points studied (see supplementary material and figures). Briefly, we found the number of positive cells was greater at position −1.46 mm from bregma in BMA in the heroin-treated group than saline-treated controls on both acute (12-hour) and extended (14-day) spontaneous withdrawal from escalating-dose heroin (both p<0.05; data not shown). Also we found the number of positive cells was greater at position −1.58 mm from bregma in DG in the heroin-treated group than saline-treated controls after extended (14-day) spontaneous withdrawal from escalating-dose heroin (p<0.05; data not shown).

4. Discussion

The present study used an escalating-dose paradigm of chronic heroin exposure in mice that was designed to mimic the dosing patterns and drug history seen in human addicts (e.g., Dole et al., 1966, Kreek et al., 2009). Using this clinically relevant paradigm, we find alteration of POMC expression in the MeA, BMA and DG as well as ARC at various withdrawal periods from chronic escalating-dose heroin exposure in mice, at periods when aversive behavior, CPA, occurred. These results support the idea that in heroin addiction, there are persistent changes in the endorphin/MOP-r system (Kreek, 1996). In heroin-dependent individuals without MOP-r agonist or partial agonist treatment (methadone or buprenorphine), the negative affective, emotional and physiological responses that characterize the withdrawal state are thought to be driven, in part, by some of these endorphin/MOP-r changes, but to date no study has systematically evaluated this possibility using a clinically relevant model of addiction. Our results revealed widespread changes to the endorphin/MOP-r system that emerge in parallel to the aversive state of withdrawal associated with discontinued heroin exposure.

Although CPA has been used to measure the aversive state of withdrawal (Spanagel et al., 1994, Rothwell et al., 2009), few studies have examined the strength or persistence of CPA across an extended heroin withdrawal period. In the present study, heroin-treated mice displayed robust CPA after acute spontaneous withdrawal (12h), and this CPA persisted across the extended (14d) withdrawal period. These results systematically extend previous reports in which mice chronically exposed to morphine expressed CPA after six days of spontaneous morphine withdrawal (Contarino and Papaleo, 2005).

Heroin, morphine and other short-acting mu agonists regulate the activity of endogenous opioid systems. It is well known that the expression of the POMC gene is mainly restricted to the ARC and the NST. However, little is known about either the regulation of POMC gene expression by chronic mu-agonist exposure, or the potential roles of POMC-derived peptides in other extra-hypothalamic regions, and their involvement in the neurobiology of heroin addiction. It has been reported that POMC transgenic mice with a different construct than the mice used in the current study also showed POMC expression in the DG (Overstreet et al., 2004). The GENSAT project reported that POMC-EGFP positive neurons are found in mesocorticolimbic regions, which include the amygdala, hippocampus, ventral striatum, and caudate-putamen (www.gensat.org) (Gong et al., 2003), in POMC BAC transgenic mice. Furthermore, our laboratory and others have also detected POMC mRNA in brain regions such as the amygdala, cerebral cortex, nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, and striatum, although in lower levels than in the ARC (Civelli et al., 1982, Zhou et al., 1996, Grauerholz et al., 1998). In the current study, we observed POMC-EGFP positive cells in the DG, the MeA and BMA, and, as expected, in the ARC. More importantly, we found that both POMC-EGFP expression and POMC mRNA levels are altered in the hippocampus, amygdala and hypothalamus at distinct points across an extended withdrawal period from chronic escalating doses of heroin. We therefore focused on these three regions.

Alteration of POMC expression found in this study could be due to the memory of withdrawal during conditioning, chronic heroin exposure itself, or their combination. It is unlikely that POMC expression could be altered by 30 min post-test of CPA.

Hypothalamic POMC neurons have been associated with several physiological functions and behaviors, such as regulation of eating, respiration and limbic excitability, pain perception and analgesia, drug addiction, sexual behavior, locomotion, learning and memory, cardiovascular homeostasis and hypophyseal hormone secretion (Kiefer and Wiedemann, 2004). In early studies using morphine pellets, several research groups have shown that POMC mRNA in the hypothalamus in rats is decreased after chronic morphine pellets (Mocchetti et al., 1989, Bronstein et al., 1990). In the current study, we found POMC expression to be decreased during acute spontaneous withdrawal. Together, these findings incorporate a “relative endogenous opioid-deficiency hypothesis” which we generated by showing relative inactivity of the mu opioid receptor inhibitory effects on regulating stress responsivity.

Intriguingly, POMC expression in the DG changed dynamically across withdrawal, decreasing during acute withdrawal and increasing during extended withdrawal. It has been proposed that POMC in the DG may reflect neurogenesis. In fact, NeuroD1, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that has been implicated in neuronal differentiation (Miyata et al., 1999, Schwab et al., 2000), is implicated in cell-specific transcription of POMC gene expression (Poulin et al., 2000). Specifically, changes in POMC-EGFP positive cells are associated with aging and exercise, suggesting that POMC-EGPF positive cells in the hippocampus could be a marker for alterations in neurogenesis. Overstreet and colleagues showed that POMC-EGFP positive cells increased after exercise on a running wheel for 4 weeks (Overstreet et al., 2004), which had also been shown to increase cell proliferation and survival of new neurons in the hippocampus (van Praag et al., 1999). Moreover, the number of POMC-EGFP positive cells in the hippocampus was lower in sixteen-month old mice compared to three-month-old mice (Overstreet et al., 2004), likely reflecting the negative relationship between aging and neurogenesis (Kuhn et al., 1996). In the present study, levels of POMC mRNA in the hippocampus were significantly reduced during acute spontaneous withdrawal from chronic escalating-dose heroin exposure; there was also a trend toward decreased numbers of POMC-EGFP positive cells in these heroin-withdrawn animals. Chronic or repeated exposure to morphine, either via pellet implantation in mice and rats, or via experimenter-administered injections in rats, robustly and reliably decreases proliferation and neurogenesis in the DG (Eisch et al., 2000), suggesting a possible mechanism by which POMC levels may be reflecting altered neurogenesis across withdrawal. After extended (14d) withdrawal, the number and total intensity of POMC-EGFP positive cells, as well as levels of POMC mRNA, were elevated compared to the control group in the hippocampus. To our knowledge, hippocampal neurogenesis has not been studied across extended withdrawal from chronic opiate exposure. However, reports on long-term withdrawal from enriched environmental stimuli have revealed that rats had 2.5 times as many proliferating cells in the DG as mice that remained in the enriched environment and in non-enriched controls (Kempermann and Gage, 1999). Although further studies are required to examine the relationship between POMC levels and neurogenesis, it is likely that extended withdrawal from chronic heroin administration is associated with altered hippocampal neurogenesis.

The amygdala is a heterogeneous structure that has been implicated in a wide variety of functions such as fear conditioning (Rogan and LeDoux, 1996), reward behaviors (Will et al., 2004, Lu et al., 2005), anxiety-like behaviors (Davis and Shi, 2000), the stress response (Herman et al., 2003), and social processes (Newman, 1999), including sexual behavior (Segovia and Guillamon, 1993, Wood, 1998) and social recognition (Ferguson et al., 2001, Choleris et al., 2007), and it is thought to be that the MeA integrates socially relevant olfactory inputs from the main and accessory olfactory system (Beauchamp and Yamazaki, 2003, Dulac and Torello, 2003, Johnston and Peng, 2008, Kang et al., 2009). The lateral and basolateral subdivisions of the amygdala receive afferent inputs from sensory processing areas implicated in addiction-related behaviors in response to heroin (Rizos et al., 2005, Zhou et al., 2008). In contrast, the central nucleus of the amygdala has been viewed as the major output nucleus to a network of neural structures implicated in responses to morphine (Glass et al., 2008), and heroin (Shalev et al., 2001). However, the role and function of the MeA and BMA in addiction-related behaviors remain unclear. The MeA is known to be involved in the stress response, as c-fos expression in the MeA is induced by various emotional or psychological stressors such as restraint stress (Chen and Herbert, 1995) and foot shock stress (Li and Sawchenko, 1998), The neurons in MeA also projects to the medial hypothalamus (Canteras et al., 1995) and may play a critical role in activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in response to emotional stressors (Dayas et al., 1999). Furthermore, activation of c-Fos expression, following naloxone- and naltrexone-precipitated morphine withdrawal, has been found in the MeA in the rat (Georges et al., 2000, Jin et al., 2004). Thus, in terms of drug addiction, it may be thought that MeA has a highly specialized role in emotional stress processing. In the present study, the number of POMC-EGFP positive cells was lower in the MeA after 7 days of spontaneous withdrawal from escalating doses of heroin. Together, these data suggest that POMC is involved in stress-related responses during mid-range withdrawal from escalating doses of heroin.

There is limited information about the function of the BMA based on specific physiological manipulations. Anatomically, this structure is known to project to anxiety-related areas including the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis and the nucleus accumbens (Canteras et al., 1992, Petrovich et al., 1996). The BMA is considered to be part of the basolateral complex involved in controlling fear responses, depression, and anxiety-like behaviors (Goosens and Maren, 2001, Hale et al., 2006, Martinez et al., 2011). Exposure to an open-field apparatus, used to measure anxiogenic responses, leads to increased c-fos expression in the BMA of the rat (Hale et al., 2006). Here, we found that the number of the POMC-EGFP positive cells was increased in BMA after acute (12 hr) and extended (14 days) spontaneous withdrawal from escalating doses of heroin. This finding suggests that POMC in BMA is involved in the response of the anxiety/fear caused by heroin withdrawal.

This study reveals the existence of POMC-EGPF positive cells in the MeA and BMA, in addition to the DG and ARC, extending previous reports. Withdrawal from escalating-dose heroin administration induced conditioned place aversion that persisted across an extended withdrawal period. Furthermore, different withdrawal time periods are associated with distinct patterns of POMC expression in different brain regions. This is the first study to characterize that POMC expression in hypothalamus and extrahypothalamic regions is changed during spontaneous withdrawal from heroin mimicking the pattern of heroin taking of the human addict. Future studies may explore the role of POMC in specific brain regions at particular times across the withdrawal periods. The current study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between POMC and addiction-like behaviors, particularly the negative affective/emotional states, such as dysphoria, that can lead to chronically relapsing drug-taking motivation across the withdrawal period.

Highlight.

POMC-EGFP positive cells are expressed in BMA, MeA and DG, besides ARC

CPA was found in spontaneous acute and extended heroin withdrawal

In BMA, POMC-EGFP cells were increased in acute and extended withdrawal

In DG, POMC-EGFP cells were increased in extended withdrawal

Altered expression of POMC in BMA and DG is associated with withdrawal-induced CPA

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from NIH-NIDA P60-DA05130 (MJK). This study was also generously supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Essel Foundation in support of KN. Diacetylmorphine hydrochloride was generously provided by the NIH-NIDA Division of Drug Supply and Analytical Services. We would like to thank Drs. Eduardo Butelman, Katharine Seip-Cammack, and Collene Lawhorn for instructive comments during preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Ms. Susan Russo for proofreading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, pertaining to any aspect of the work reported in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

KN, YZ and MJK conceived the general ideas for this study and designed the experiments. KN performed the experiments, data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AH assisted in statistical analysis and writing of the manuscript. All authors provided input into the writing of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed SH, Walker JR, Koob GF. Persistent increase in the motivation to take heroin in rats with a history of drug escalation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp GK, Yamazaki K. Chemical signalling in mice. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:147–151. doi: 10.1042/bst0310147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein DM, Przewlocki R, Akil H. Effects of morphine treatment on pro-opiomelanocortin systems in rat brain. Brain Res. 1990;519:102–111. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90066-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Connections of the posterior nucleus of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:143–179. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the medial nucleus of the amygdala: a PHAL study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;360:213–245. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SA, O’Dell LE, Hoefer ME, Greenwell TN, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Unlimited access to heroin self-administration: independent motivational markers of opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2692–2707. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Herbert J. Regional changes in c-fos expression in the basal forebrain and brainstem during adaptation to repeated stress: correlations with cardiovascular, hypothermic and endocrine responses. Neuroscience. 1995;64:675–685. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00532-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choleris E, Little SR, Mong JA, Puram SV, Langer R, Pfaff DW. Microparticle-based delivery of oxytocin receptor antisense DNA in the medial amygdala blocks social recognition in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4670–4675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700670104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civelli O, Birnberg N, Herbert E. Detection and quantitation of pro-opiomelanocortin mRNA in pituitary and brain tissues from different species. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6783–6787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contarino A, Papaleo F. The corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-1 pathway mediates the negative affective states of opiate withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18649–18654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506999102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Kalant H. Heroin self-administration by rats: influence of dose and physical dependence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Shi C. The amygdala. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R131. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, Buller KM, Day TA. Neuroendocrine responses to an emotional stressor: evidence for involvement of the medial but not the central amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2312– 2322. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole VP, Nyswander ME, Kreek MJ. Narcotic blockade--a medical technique for stopping heroin use by addicts. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1966;79:122–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C, Torello AT. Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals: from genes to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:551–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Schad CA, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7579–7584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120552597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ. Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8278–8285. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08278.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. California: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gellert VF, Holtzman SG. Development and maintenance of morphine tolerance and dependence in the rat by scheduled access to morphine drinking solutions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;205:536–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges F, Stinus L, Le Moine C. Mapping of c-fos gene expression in the brain during morphine dependence and precipitated withdrawal, and phenotypic identification of the striatal neurons involved. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4475–4486. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass MJ, Hegarty DM, Oselkin M, Quimson L, South SM, Xu Q, Pickel VM, Inturrisi CE. Conditional deletion of the NMDA-NR1 receptor subunit gene in the central nucleus of the amygdala inhibits naloxone-induced conditioned place aversion in morphine-dependent mice. Exp Neurol. 2008;213:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, Losos K, Didkovsky N, Schambra UB, Nowak NJ, Joyner A, Leblanc G, Hatten ME, Heintz N. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosens KA, Maren S. Contextual and auditory fear conditioning are mediated by the lateral, basal, and central amygdaloid nuclei in rats. Learn Mem. 2001;8:148–155. doi: 10.1101/lm.37601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauerholz BL, Jacobson JD, Handler MS, Millington WR. Detection of pro-opiomelanocortin mRNA in human and rat caudal medulla by RT-PCR. Peptides. 1998;19:939–948. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudehithlu KP, Tejwani GA, Bhargava HN. Beta-endorphin and methionine-enkephalin levels in discrete brain regions, spinal cord, pituitary gland and plasma of morphine tolerant-dependent and abstinent rats. Brain Res. 1991;553:284–290. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90836-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale MW, Bouwknecht JA, Spiga F, Shekhar A, Lowry CA. Exposure to high- and low-light conditions in an open-field test of anxiety increases c-Fos expression in specific subdivisions of the rat basolateral amygdaloid complex. Brain Res Bull. 2006;71:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Cullinan WE. Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Araki H, Nagata M, Suemaru K, Shibata K, Kawasaki H, Hamamura T, Gomita Y. Withdrawal-induced c-Fos expression in the rat centromedial amygdala 24 h following a single morphine exposure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175:428–435. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RE, Peng A. Memory for individuals: hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) require contact to develop multicomponent representations (concepts) of others. J Comp Psychol. 2008;122:121–131. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.122.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang N, Baum MJ, Cherry JA. A direct main olfactory bulb projection to the ‘vomeronasal’ amygdala in female mice selectively responds to volatile pheromones from males. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:624–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Gage FH. Experience-dependent regulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis: effects of long-term stimulation and stimulus withdrawal. Hippocampus. 1999;9:321–332. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:3<321::AID-HIPO11>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, Wiedemann K. Neuroendocrine pathways of addictive behaviour. Addict Biol. 2004;9:205–212. doi: 10.1080/13556210412331292532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ. Opiates, opioids and addiction. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:232–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Schlussman SD, Reed B, Zhang Y, Nielsen DA, Levran O, Zhou Y, Butelman ER. Bidirectional translational research: Progress in understanding addictive diseases. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzich PJ, Chen AC, Unterwald EM, Kreek MJ. Subject-regulated dosing alters morphine self-administration behavior and morphine-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding. Synapse. 2003;47:243–249. doi: 10.1002/syn.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2027–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langerman L, Piscoun B, Bansinath M, Shemesh Y, Turndorf H, Grant GJ. Quantifiable dose-dependent withdrawal after morphine discontinuation in a rat model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HY, Sawchenko PE. Hypothalamic effector neurons and extended circuitries activated in “neurogenic” stress: a comparison of footshock effects exerted acutely, chronically, and in animals with controlled glucocorticoid levels. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:244–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Hope BT, Dempsey J, Liu SY, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. Central amygdala ERK signaling pathway is critical to incubation of cocaine craving. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:212–219. doi: 10.1038/nn1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez RC, Carvalho-Netto EF, Ribeiro-Barbosa ER, Baldo MV, Canteras NS. Amygdalar roles during exposure to a live predator and to a predator-associated context. Neuroscience. 2011;172:314–328. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T, Maeda T, Lee JE. NeuroD is required for differentiation of the granule cells in the cerebellum and hippocampus. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1647–1652. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocchetti I, Ritter A, Costa E. Down-regulation of proopiomelanocortin synthesis and beta-endorphin utilization in hypothalamus of morphine-tolerant rats. J Mol Neurosci. 1989;1:33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02896854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman SW. The medial extended amygdala in male reproductive behavior. A node in the mammalian social behavior network. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:242–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niikura K, Narita M, Nakamura A, Okutsu D, Ozeki A, Kurahashi K, Kobayashi Y, Suzuki M, Suzuki T. Direct evidence for the involvement of endogenous beta-endorphin in the suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect under a neuropathic pain-like state. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet LS, Hentges ST, Bumaschny VF, de Souza FS, Smart JL, Santangelo AM, Low MJ, Westbrook GL, Rubinstein M. A transgenic marker for newly born granule cells in dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3251–3259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5173-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich GD, Risold PY, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the basomedial nucleus of the amygdala: a PHAL study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;374:387–420. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961021)374:3<387::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picetti R, Caccavo JA, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Dose escalation and dose preference in extended-access heroin self-administration in Lewis and Fischer rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;220:163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto S, Roseberry AG, Liu H, Diano S, Shanabrough M, Cai X, Friedman JM, Horvath TL. Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science. 2004;304:110–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1089459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin G, Lebel M, Chamberland M, Paradis FW, Drouin J. Specific protein-protein interaction between basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors and homeoproteins of the Pitx family. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4826–4837. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4826-4837.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizos Z, Ovari J, Leri F. Reconditioning of heroin place preference requires the basolateral amygdala. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan MT, LeDoux JE. Emotion: systems, cells, synaptic plasticity. Cell. 1996;85:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell PE, Thomas MJ, Gewirtz JC. Distinct profiles of anxiety and dysphoria during spontaneous withdrawal from acute morphine exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2285–2295. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlussman SD, Cassin J, Zhang Y, Levran O, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Regional mRNA expression of the endogenous opioid and dopaminergic systems in brains of C57BL/6J and 129P3/J mice: strain and heroin effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;100:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab MH, Bartholomae A, Heimrich B, Feldmeyer D, Druffel-Augustin S, Goebbels S, Naya FJ, Zhao S, Frotscher M, Tsai MJ, Nave KA. Neuronal basic helix-loop-helix proteins (NEX and BETA2/Neuro D) regulate terminal granule cell differentiation in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3714–3724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03714.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia S, Guillamon A. Sexual dimorphism in the vomeronasal pathway and sex differences in reproductive behaviors. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:51–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90007-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip KM, Reed B, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Measuring the incentive value of escalating doses of heroin in heroin-dependent Fischer rats during acute spontaneous withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2380-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Morales M, Hope B, Yap J, Shaham Y. Time-dependent changes in extinction behavior and stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking following withdrawal from heroin in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:98–107. doi: 10.1007/s002130100748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Almeida OF, Bartl C, Shippenberg TS. Endogenous kappa-opioid systems in opiate withdrawal: role in aversion and accompanying changes in mesolimbic dopamine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;115:121–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02244761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will MJ, Franzblau EB, Kelley AE. The amygdala is critical for opioid-mediated binge eating of fat. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1857–1860. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200408260-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI. Integration of chemosensory and hormonal input in the male Syrian hamster brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;855:362–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Leri F, Cummins E, Hoeschele M, Kreek MJ. Involvement of arginine vasopressin and V1b receptor in heroin withdrawal and heroin seeking precipitated by stress and by heroin. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:226–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Spangler R, LaForge KS, Maggos CE, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Modulation of CRF-R1 mRNA in rat anterior pituitary by dexamethasone: correlation with POMC mRNA. Peptides. 1996;17:435–441. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]