Abstract

The efficacy of biological therapeutics against cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis is restricted by the limited transport of macromolecules through the dense, avascular extracellular matrix. The availability of biologics to cell surface and matrix targets is limited by steric hindrance of the matrix, and the microstructure of matrix itself can be dramatically altered by joint injury and the subsequent inflammatory response. We studied the transport into cartilage of a 48 kDa anti-IL-6 antigen binding fragment (Fab) using an in vitro model of joint injury to quantify the transport of Fab fragments into normal and mechanically injured cartilage. The anti-IL-6 Fab was able to diffuse throughout the depth of the tissue, suggesting that Fab fragments can have the desired property of achieving local delivery to targets within cartilage, unlike full-sized antibodies which are too large to penetrate beyond the cartilage surface. Uptake of the anti-IL-6 Fab was significantly increased following mechanical injury, and an additional increase in uptake was observed in response to combined treatment with TNFα and mechanical injury, a model used to mimic the inflammatory response following joint injury. These results suggest that joint trauma leading to cartilage degradation can further alter the transport of such therapeutics and similar-sized macromolecules.

Keywords: cartilage, TNFα, Fab, transport, injury, osteoarthritis

1. Introduction

Proinflammatory cytokines are key mediators involved in the pathogenesis of both osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The roles of predominant cytokines in cartilage destruction have been extensively studied in efforts to find effective therapeutic targets for these arthritic diseases [1, 2]. Monoclonal antibodies against specific cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6 are now administered to RA patients by systemic infusion or subcutaneous injection [3, 4]. Following the success of these biological therapies for RA, similar approaches have been under study to target selected cytokines for OA [1, 2]. However, since OA involves the local pathophysiology of specific joint tissues, systemic administration of biologics may not be efficacious and may increase the risk of side effects [5]. Intra-articular (IA) injection directly to affected joints is therefore advantageous, and may better control the concentration of a desired drug in the joint space.

Despite the potential benefits of IA injection, the effect of biologics against cartilage degradation in OA is significantly compromised by limited transport into and through the tissue's dense extracellular matrix (ECM). Previous studies by Maroudas showed that large solutes are sterically excluded by ECM proteoglycans (mainly aggrecan), and that full-size immunoglobulin (IgG) antibodies (150 kDa) cannot penetrate into cartilage ECM to reach cellular therapeutic targets [6]. Since the extent of steric hindrance by the ECM depends on the size of solute, smaller-sized antibody fragments (e.g., 48 kDa Fab fragments or 26 kDa single-chain Fv (ScFv)), should be able to penetrate the ECM while maintaining their biological activity. For example, a ScFv against TNFα showed a similar inhibitory effect but also an increased tissue penetration compared to its full-sized counterpart [7]. 40 kDa dextrans, which have similar molecular weight to Fab fragments, are capable of diffusing into cartilage [8–10]. However, to our knowledge, there has been no direct study of the transport of Fab antibodies into and within cartilage. Thus, the ability of a Fab to reach intra-cartilage targets as a potential OA therapeutic has not been confirmed.

Recent attention to the role of IL-6 in post-traumatic OA has motivated the potential use of anti-IL-6 therapeutics for OA [1]. Sui and co-workers showed that GAG loss from cartilage explants induced by the combination of mechanical injury and co-incubation with TNFα in vitro was reduced by treatment with an anti-IL-6 Fab fragment [11]. Thus, upregulation of endogenous IL-6 by these degradative stimuli was responsible in part for the observed cartilage degradation. However, it was not known whether the partial effectiveness of the anti-IL-6 Fab was associated with transport limitations into the tissue. In addition, transport of macromolecular solutes into cartilage can be dramatically affected by binding of the solutes to sites in the ECM; the resulting diffusion-reaction transport kinetics can lead to an effective solute diffusivity that is orders of magnitude lower than that in the absence of binding [12]. Therefore, studies of Fab transport into cartilage should examine the possibility of binding of the Fab within the ECM.

Damage to cartilage following traumatic joint injury and the subsequent inflammatory response in vivo may alter the cartilage transport properties, since matrix hindrance to molecular transport will be affected by changes in the structure, composition and hydration of cartilage ECM [6, 9, 13]. Such changes in ECM transport properties caused by combined mechanical injury and inflammatory cytokines have not been studied in detail. Several groups have used ECM proteolysis in vitro, e.g., using trypsin, to mimic cartilage degeneration, and found increased solute diffusivity and partition coefficient after GAG loss [14–18]. However, injurious compression as occurs during joint trauma [19] additionally causes tissue swelling, collagen damage and denaturation, GAG loss, and decreased ECM integrity [20]. Furthermore, the interaction between exogenous cytokines and cartilage mechanical injury is known to cause synergistic loss of proteoglycans which, taken together, suggest the possibility of substantial changes in tissue transport properties [11, 20–26].

Motivated by these previous reports, the objectives of this study were (1) to quantify the transport of anti-IL-6 Fab fragment in articular cartilage, and (2) to characterize the changes in transport of anti-IL-6 Fab following mechanical injury and simultaneous treatment with the inflammatory cytokine TNFα. Diffusive transport of Fab was quantified and its spatial distribution in cartilage tissue was visualized. A competitive binding assay was performed to confirm whether or not the anti-IL-6 Fab could bind to cartilage ECM. Changes in transport of the anti-IL-6 Fab were compared to measured changes in tissue hydration and GAG density.

2. Materials and Methods

Bovine tissue harvest

Bovine articular cartilage explants were harvested from the femoropatellar grooves of 1–2 weeks old calves (Research 87, Marlborough, MA) as described previously [27]. A total of 12 joints from 6 different animals were used. Briefly, 9-mm diameter cartilage-bone cylinders were drilled perpendicularly to the surface and mounted on a microtome. After obtaining a level surface by removing the top superficial layer, 1–2 sequential 1-mm thick middle zone slices were cut. Finally, four or five disks (3-mm diameter, 1-mm thick) were cored from each slice using a dermal punch. Explants were matched for location and depth across treatment groups. All cartilage specimens were equilibrated either in serum-free medium (low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM; 1 g/L]) supplemented with 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (10 μg/mL, 5.5 μg/mL, and 5 ng/mL, respectively) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 10 mM HEPES buffer, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 0.4 mM proline, 20 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 100 units/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator or in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.01% sodium azide (NaN3) and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) at 4°C prior to experiments.

Postmortem adult human tissue

A knee joint from a human subject (26-year-old woman) was obtained 36 hr postmortem from the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network (Elmhurst, IL). All procedures were approved by the Office of Research Affairs at Rush–Presbyterian–St. Luke's Medical Center and the Committee on Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All joint surfaces of this knee joint were scored according to modified Collins scale [28] as grade 0–1, and only cartilage from visually unfibrillated areas were harvested for this study. After coring 3-mm diameter cartilage disks from the femoropatellar groove and femoral condyles using a dermal punch, 0.8-mm thick slices were cut from the top-most surface including the intact superficial zone. These human cartilage disks (3-mm diameter, 0.8-mm thick) were cultured using the same methods as above for bovine tissue, except that culture medium for human tissue contained high-glucose DMEM (4.5 g/L) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate.

Solute preparation

Iodinated 48 kDa Fab fragment (125I-Fab) and unlabeled Fab raised against the inflammatory cytokine, IL-6, were kindly provided by Janssen Research & Development, LLC [11]. Before performing experiments with the 125I-Fab, Sephadex G50 chromatography was used to separate and remove any small 125I-species that may have resulted from degradation of 125I-Fab (0.7 × 50 cm gravity-fed column equilibrated in 1×PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.01% NaN3, and the void volume collected to obtain the purified 125I-Fab) [12].

Measurement of 125I-Fab uptake into bovine cartilage

In order to measure the partitioning of Fab fragments into cartilage, free-swelling bovine calf cartilage disks were incubated at 4°C up to 8 days in a buffer containing 125I-Fab (5.01 nM) without unlabeled Fab. Multi-well plates containing equilibration baths and cartilage explants were placed on a rocker to maintain continuously well-mixed conditions. The amount of Fab in cartilage disks was quantified using an uptake ratio calculated as the measured concentration of 125I-Fab in the disks (per intratissue water weight) normalized to the concentration of 125I-Fab in the equilibration bath [12, 29]. The buffer consisted of 1×PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% NaN3 and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). At selected time points, disks were collected from the bath and briefly rinsed in fresh PBS. The surface of each disk was quickly blotted with Kimwipes and the wet weight was measured. The amount of 125I-radioactivity of each disk and aliquots of the equilibration baths were measured individually using a gamma counter (model B5002, Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, CT). Disks were then lyophilized and the dry weight was measured. Water weight was then calculated as the difference of wet and dry weights. To take into account the accumulation of any small labeled species (e.g., 125I) from the degradation of 125I-Fab during each experiment and correct the uptake ratio for the presence of these small species, samples of the equilibration baths were analyzed by Sephadex G50 chromatography at the end of each experiment. Assuming the small species to be 125I, the uptake ratio of 125I alone was measured in separate experiment to calibrate the correction factor [30].

Autoradiography of human cartilage disks

Free swelling human cartilage disks with intact superficial zone were incubated with 125I-Fab with no unlabeled Fab at 37°C for 3 days in 1×PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% NaN3 and protease inhibitors. Collected cartilage disks at the end of experiment were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept frozen at −80°C. Briefly, slides containing cryosections of 5 μm thickness were dipped into Kodak NTB-2 emulsion, followed by drying at room temperature, and exposure at 4°C for up to 3 weeks. After the exposure period, the slides were developed in Kodak D-19 developer. Each slide was lightly section-stained with 0.001% toluidine blue in buffer (2% boric acid, 1% sodium tetraborate, pH 7.6) and viewed by light microscopy using ×10 and ×40 objectives [31]. To quantify the depth-dependence of autoradiography grain intensity, images were converted to grayscale, inverted, and 20–40 μm wide vertical sections of the images were chosen that avoided cells. Within these sub-images, grains in each horizontal row were summed to calculate a relative grain density as a function of depth. The resulting densitometry data were smoothed using a running average algorithm with a window size of approximately 40 μm.

Concentration dependent uptake ratio

To determine whether Fab may bind to sites within the bulk of the tissue, bovine calf cartilage disks under free-swelling condition were incubated in a buffer containing 125I-Fab (5.01 nM for experiments at 4°C and 2.21 nM for experiments at 37°C) with graded amounts of unlabeled Fab (0, 10, 100, and 1000 nM). The uptake ratio was measured at 4°C as well as 37°C since the studies at 4°C provide measurements under conditions when potential effects of matrix degradation, cellular activity and artifactual degradation of iodinated proteins over time are minimized. The buffer consisted of 1×PBS with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% NaN3 and protease inhibitors at 4°C or DMEM with 1% ITS and 0.1% BSA at 37°C. Cartilage disks were incubated for 5 days and the uptake ratio at each condition was quantified as described above.

Effecst of injurious compression on uptake ratio and tissue swelling

Bovine calf cartilage disks were subjected to a single injurious compression in a custom-designed, incubator-housed loading apparatus [20, 32]. Briefly, each individual disk was placed between impermeable platens of a polysulfone chamber, in a radially unconfined compression configuration. During injury loading, the disk was compressed to 50% final strain with a constant velocity of 1 mm/s (strain rate 100%/s) and then immediately released at the same rate. This injury protocol resulted in a peak stress of ~ 20 MPa, which is known to produce ECM damage, reduced mechanical properties, decreased biosynthesis, increased GAG loss to media, and approximately 10–20% cell death [20–23]. Untreated and injured cartilage disks were then incubated under free swelling conditions for 6 days with 125I-Fab without unlabeled Fab at 4°C in 1×PBS with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% sodium azide, and protease inhibitors. At the end of experiment, disks were collected to measure the uptake ratio. Wet and dry weights of cartilage disks were used to calculate tissue hydration and water content. Tissue hydration was defined as tissue water weight (mg) normalized by dry weight (mg).

Effects of exogenous cytokines combined with mechanical injury

To test the effect of exogenous cytokines combined with mechanical injury on the uptake of 125I-Fab, bovine calf cartilage disks were subjected to no treatment (control), mechanical injury, exogenous TNFα (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), or the combination of injury and TNFα. Uptake of 125I-Fab in these same four conditions was then measured under conditions of sustained 10% static compression: normal or mechanically injured 3-mm diameter × 1-mm thick bovine disks were first compressed by 10% in the same loading chamber, then incubated with 125I-Fab plus unlabeled Fab (10 μg/ml) with or without TNFα (2.5 ng/ml for day 0–2, 25 ng/ml for day 2–6). Under 10% offset static compression, only 1-dimensional (radial) diffusion was allowed from the bath to the disk center. The medium was replaced every 2 days and saved for further analysis. At day 2, 4, and 6, disks were collected and processed to measure the uptake ratio. Disks were then digested with proteinase-K (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). The dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) dye binding assay was used to measure the sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) content of each disk and also the amount sGAG release from the disk to the media [27].

Statistical Analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of unlabeled Fab concentration and temperature on the uptake. The effect of injurious compression on the uptake ratio and tissue swelling was tested with two-way ANOVA using the injury and time as factors. The effects of mechanical injury and TNFα on the uptake ratio, tissue hydration, and GAG density were evaluated by two-way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc Tukey test. For all statistical test, p-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant. Systat 12 software (Richmond, CA) was used to perform all analyses.

3. Results

Anti-IL-6 Fab fragment (48 kDa) was able to penetrate into cartilage explants

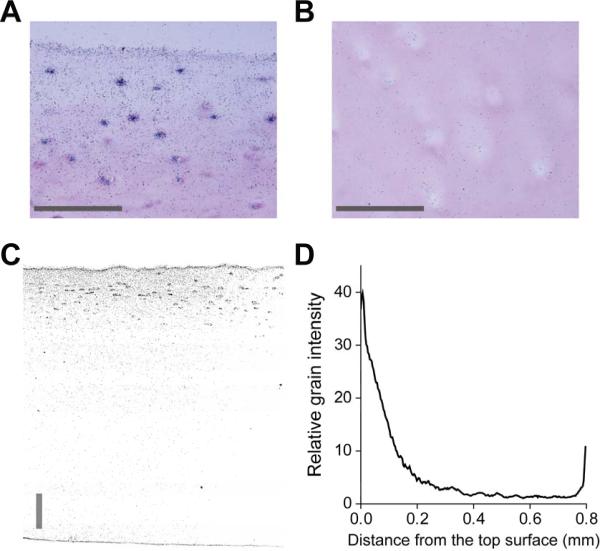

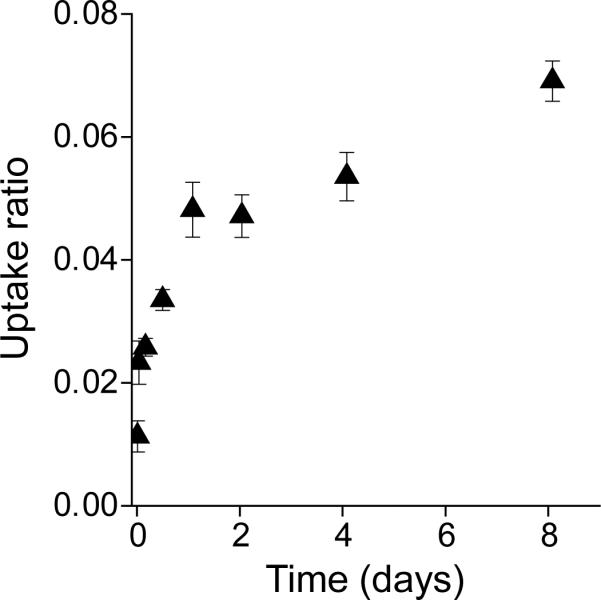

The uptake of 125I-Fab was measured daily during a 9-day incubation of middle zone bovine disks to evaluate the ability of the fab fragment to penetrate into cartilage by simple diffusion (Fig. 1). The uptake ratio of 125I-Fab increased continuously, suggesting the accumulation of the solute within the disk. Due to its large size, diffusion of the Fab was relatively slow, similar to that reported previously for other similarly sized solutes [6]. However, the time-dependent increase in uptake ratio does not necessarily mean full penetration of Fab fragment beyond the outer surfaces of the explant disks. Non-specific binding or adsorption to the outer surfaces could also result in an apparent increase in the accumulation of 125I-Fab [33], leading to an increase in calculated uptake measurement whether or not the Fab penetrated into deeper regions of the tissue. To confirm qualitatively whether 125I-Fab could diffuse more deeply into the tissue, the spatial distribution of 125I-Fab was visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 2). Human knee cartilage disks including the intact superficial zone were incubated with 125I-Fab without unlabeled Fab at 37°C for 3 days; 125I-Fab could thereby enter the disks from the top and the bottom surfaces. Autoradiography revealed that 125I-Fab was detectable throughout the tissue at day 3, though there was still a pronounced gradient in the grain density which was higher in the superficial zone than the deeper zones (Fig. 2). This observation is qualitatively consistent with the known higher concentration of aggrecan in the middle and deep zones compared to the superficial zone, enabling the 125I-Fab to enter more quickly from the superficial zone. The apparent high grain intensity at the very top and bottom surfaces (Fig. 2d) may be due to adsorption to these surfaces [33]; nevertheless, full penetration of 125I-Fab into the disks by simple diffusion was clear at day 3, and equilibrium partitioning throughout the depth could thus occur given sufficient time. Since the Fab did not appear to bind reversibly to specific sites within the bulk cartilage tissue (see Fig. 3 below), each data point of Fig. 1 can be interpreted as the integrated sum of 125I-Fab molecules that are distributed in a spatially non-uniformly profile inside each disk prior to final equilibrium.

Figure 1.

Uptake ratio of 125I-Fab in bovine calf cartilage disks incubated at 4°C under free-swelling conditions without unlabeled Fab in 1×PBS with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% sodium azide, and protease inhibitors. Mean ± SEM (n = 5–6 disks at each time point, harvested from 2 joints).

Figure 2.

Autoradiography images of 125I-Fab distributed within human knee cartilage explants at day 3. Cartilage disks were harvested from first ~ 800 μm layer of grade 0–1 human knee cartilage including the intact superficial zone. Free-swelling cartilage disks were incubated in medium containing 125I-Fab without unlabeled Fab at 37°C for 3 days in 1×PBS with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% sodium azide, and protease inhibitors. The 125I-Fab penetrated throughout the human tissue but still exhibited a pronounced gradient in grain density with depth at day 3, showing a more concentrated distribution of 125I-Fab in the upper region near the surface (A), compared to that approximately 500–600 μm below the surface (B). Distribution of 125I-Fab across the full thickness from the same disk (C) was consistent with higher magnification images (A, B), showing the gradient in the grain intensity throughout the thickness (D, relative grain intensity measured from C). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure 3.

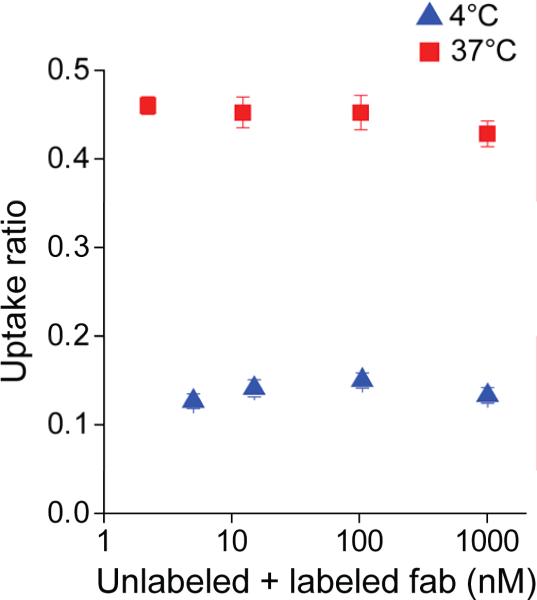

Concentration-dependent uptake ratio of 125I-Fab in bovine calf cartilage after 5 days under free swelling conditions at 4°C and 37°C. Graded amounts of unlabeled Fab (0, 10, 100, and 1000 nM) were added to a fixed concentration of 125I-Fab (5.01 nM at 4°C and 2.21 nM at 37°C). At both temperatures, the uptake ratio of 125I-Fab did not change significantly with the concentration of unlabeled Fab (2-way ANOVA, p=0.495). The uptake ratio of 125I-Fab was significantly higher at 37°C compared to 4°C (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001). Mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 disks for each condition, harvested from 2 joints).

Anti-IL-6 Fab fragment did not bind to sites in the bulk of bovine cartilage explants

To determine whether Fab fragment may bind to specific sites within the tissue, graded amounts of unlabeled Fab were added to the baths during incubation and the uptake ratio was measured at day 5 [12, 29, 34]. Competition for binding sites between labeled and unlabeled Fab would cause decreased uptake ratio of 125I-Fab with increasing concentration of unlabeled Fab. However, the data of Fig. 3 showed no significant change in uptake of 125I-Fab at either 37°C or 4°C with addition of unlabeled Fab up to 1 μM, indicating negligible competitive binding between the labeled and unlabeled Fab under these conditions [29] (2-way ANOVA, no significant effect of unlabeled Fab concentration or the interaction between temperature and concentration). The same experiment was repeated with disks from two joints each from two additional animals and showed the same trend as Fig. 3 (data not shown).

Injurious compression and exogenous TNFα altered transport of anti-IL-6 Fab into bovine knee cartilage

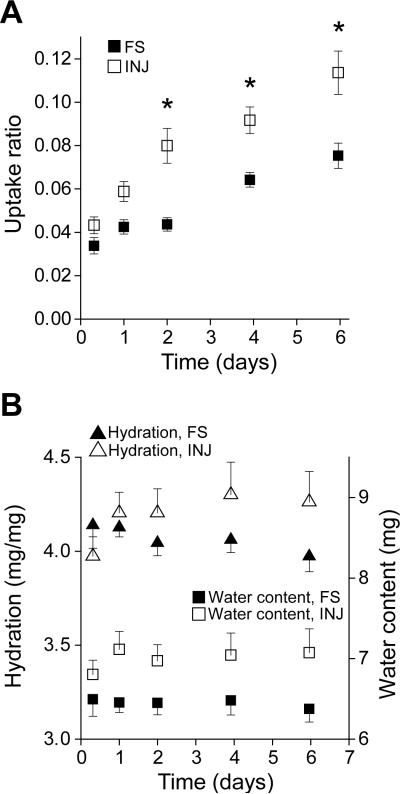

To test the effect of injurious compression alone on transport of Fab fragments into cartilage, the uptake ratio of 125I-Fab was measured after cartilage explants were subjected to a single injurious compression cycle. Injurious loading induced a significant increase in the uptake ratio of 125I-Fab compared to uninjured controls (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 for effect of injury, Fig. 4a). Mechanical injury also caused tissue swelling (Fig. 4b), as manifested in increased tissue hydration (tissue water weight/dry weight [35, 36], 2-way ANOVA, p = 0.098 for effect of injury) and water content (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 for effect of injury), consistent with previously reported effects of mechanical injury on cartilage swelling [20, 21]. These results demonstrated that a single mechanical overload of cartilage was enough to increase the micro-permeability of the matrix to Fab fragments, consistent with the increase in macroscopic matrix swelling.

Figure 4.

Effect of the mechanical injury on the uptake ratio of 125I-Fab and tissue swelling. Untreated and injured disks were incubated under free swelling conditions up to 6 days with 125I-Fab without unlabeled Fab at 4°C in 1×PBS with 0.1% BSA, 0.01% sodium azide, and protease inhibitors. A. Uptake ratio of 125I-Fab in untreated (FS) and injured (INJ) disks. Mechanical injury induced a significant increase in the uptake ratio (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 for both injury and time, * = p<0.05 by Tukey's test). B. Hydration (tissue water weight/dry weight) and water content in untreated (FS) and injured (INJ) disks. Tissue water content changed significantly after the injury (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 with injury), accompanied by an increase in hydration (2-way ANOVA, p=0.098 with injury). Mean ± SEM (n = 8 disks for each condition, harvested from 2 joints).

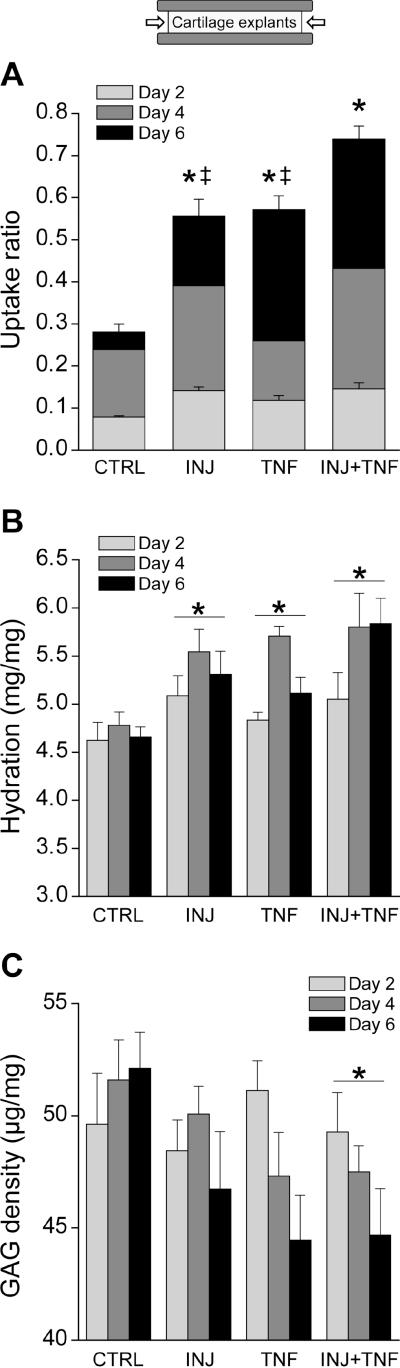

In addition, we tested the effects of exogenous TNFα, alone and combined with mechanical injury on the uptake of 125I-Fab. Treatment with injury, TNFα, and the combination of injury and TNFα each significantly increased the uptake ratio of 125I-Fab over 6 days. The combined effect of injury and TNFα induced the largest increase (post hoc Tukey's test, p<0.05, Fig. 5a). GAG release from explants to the medium showed a trend similar to the uptake ratio: mechanical injury and TNFα each significantly increased GAG release, and their combination caused the highest GAG loss, consistent with the previously reported effects of injury and exogenous cytokines on GAG loss [11, 22] (cumulative GAG loss to the media at day 6 for control, injury, TNFα, and injury with TNFα, was 7.3%, 8.9%, 16.3%, and 16.8%, respectively, data not shown). We also observed changes in tissue hydration and GAG density (GAG content/tissue water weight) after injury and cytokine treatment. Tissue hydration was significantly increased by all three treatments compared to control (Fig. 5b, post hoc Tukey's test, p<0.05), suggesting, again, that the change in tissue hydration affected the uptake ratio of 125I-Fab. Similarly, GAG density was significantly decreased after the treatment (2-way ANOVA). This result indicated that the steric hindrance imposed by tissue GAG was also responsible for the limited uptake of Fab fragment and the change in the GAG density combined with tissue swelling resulted in the greatest change in the uptake ratio.

Figure 5.

Effect of the injurious compression and exogenous TNFα on the uptake of 125I-Fab, tissue hydration, and GAG density. Cartilage disks were subjected to mechanical injury (INJ), TNFα (TNF), or the combination of injury and TNFα (INJ+TNF), with TNF concentration at 2.5 ng/ml for day 0–2 and then 25 ng/ml for day 2–6. The disks were incubated at 37°C with 125I-Fab and unlabeled Fab (10 μg/ml = 66.7 nM) in DMEM with 0.1% BSA, and 1% ITS under 10% offset static compression so that only radial diffusion could occur from the bath to the disk center (inset in A). A. Uptake ratio of 125I-Fab measured after 2, 4, and 6 days in culture. Uptake varied significantly with the treatment (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 for both treatment and time, * = p<0.05 vs. CTRL by Tukey's test, ‡ = p<0.05 vs. INJ+TNF by Tukey's test). B. Hydration (tissue water weight/dry weight) of cartilage tissue was significantly increased by the treatment (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 for the treatment, * = p<0.05 vs. CTRL by Tukey's test). C. GAG density (GAG content / water content) of cartilage disks was significantly decreased after the treatment (2-way ANOVA, p=0.042 for the treatment, * = p<0.05 vs. CTRL by Tukey's test). Mean ± SEM (n = 5 disks for each condition, harvested from 2 joints).

4. Discussion

Our results suggest that Fab fragments (48 kDa) can diffuse into and throughout the depth of 1mm-thick middle zone bovine cartilage disks. Both uptake into bovine cartilage explants and autoradiography images of human knee cartilage explants suggest that complete equilibration into full-thickness cartilage would take at least one week. There was demonstrably greater accessibility of the Fab into the cartilage after direct mechanical injury and/or treatment with the inflammatory cytokine TNFα, and the increase in uptake was related to the severity of matrix damage and GAG loss. The combination of mechanical injury and TNFα induced the most dramatic increase in the uptake, suggesting that changes in cartilage associated with traumatic joint injury [13, 19], including the immediate inflammatory response [37], could greatly alter transport processes in cartilage.

Although full-penetration of 125I-Fab into human explant disks was observed in autoradiography images, the spatial distribution was not uniform. At day 3, significant penetration of 125I-Fab was detected in the more hydrated surface regions but less in the middle and deep regions of the disks. Nevertheless, these results suggest that Fab fragments can reach targets located beyond the superficial zone of cartilage, which is a key requirement for Fab to be useful as a therapeutic if the target is located throughout the tissue thickness. In contrast, previous studies have shown that full sized monoclonal antibodies (mAb, MW ~150 kDa) cannot penetrate into cartilage beyond the top most surface regions of cartilage due to steric exclusion [6]. Thus, targets deeper within the tissue cannot be reached by mAbs. For comparison, we show lack of penetration of a fluorescently tagged anti-IL-6 mAb into native bovine cartilage (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Only when cartilage GAGs are completely removed (in this case by a 14-day pre-treatment with IL-1 and oncostatin M (OSM)) can this anti-IL-6 mAb fully penetrate into bovine cartilage (Fig. S1b).

In addition, it is important to note that anti-IL-6 Fab did not appear to bind reversibly to sites in the bovine cartilage disks (Fig. 3); such binding would have greatly slowed the diffusive transport of Fab within the cartilage matrix compared to size-restriction alone [12, 34]. For example, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) binds to specific IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) contained within cartilage ECM, and the binding of IGF-1 to these IGFBPs slows diffusive transport kinetics of IGF-1 by a factor of ~ 10 in bovine cartilage [12]. Thus, Fab can penetrate beyond the surface of the cartilage (Fig. 2) and freely diffuse into the deeper regions of the tissue at a rate dependent primarily on the local steric hindrance within the matrix. However, in the absence of binding to sites in the matrix, Fab fragments could diffuse out of the cartilage at the same rate as they diffuse in, once the Fab had been cleared from synovial fluid by the circulation [38, 39] and the inward concentration gradient was no longer sustained. Thus, the absence of binding to sites in the ECM is beneficial for achieving deeper penetration in given time, but a mechanisms for sustained delivery within cartilage and intratissue release is also needed [29, 40].

Assuming no binding of Fab fragments to sites in the tissue (based on the data of Fig. 3), the diffusivity D and partition coefficient K in our specimens can be estimated from the measured uptake ratio. As an example, the temporal increase in uptake ratio measured under free-swelling conditions of Fig. 4A (both untreated and post-mechanical injury) was fitted using a two-dimensional axisymmetric diffusion model, assuming that diffusion into the cartilage disk occurred from all surfaces (since the multi-well plates were constantly mixed). The diffusivity and partition coefficient of Fab fragments into untreated disks were estimated to be D = 3.5×10−9 cm2/s and K = 0.09, respectively. For mechanically injured disks, the diffusivity and partition coefficient increased by ~ 30% and ~ 40%, respectively. For comparison, the diffusivity and partition coefficient of 40 kDa dextran in human and animal cartilages have been reported previously to be in the ranges D ~ 1×10−8 to 6×10−8 cm2/s and K ~ 0.03–0.3, respectively [8–10].

We also observed that the uptake ratio measured at 37°C was higher than that at 4°C (Fig. 3). Previously, Torzilli used glucose and dextran (10 kDa) to test the effect of temperature on transport into adult bovine cartilage [41]. Increasing the temperature from 10°C to 37°C induced a significant increase in diffusivities and partition coefficients of glucose and dextran, suggesting that the uptake of Fab could be similarly affected by temperature. Fab uptake was indeed higher at 37° compared to 4° (Fig. 3). However, the uptake of radiolabeled Fab did not change with the addition of substantial amounts of unlabeled Fab, further supporting the conclusion that there is little or no binding of Fab to sites in the tissue.

Interestingly, Fab diffused more freely into the tissue following mechanical injury of the matrix. Mechanical loading as used in the present study induced tissue swelling, as demonstrated by the increase in tissue hydration and tissue water content (Fig. 4b). Such tissue swelling is likely caused by micro-damage to the collagen fibril network which ordinarily restricts the osmotic swelling generated by highly charged GAG chains [42]. The increased hydration and tissue water content following mechanical injury would allow Fab to move with less hindrance within the cartilage, resulting in an increased uptake ratio (e.g., Fig. 4). Compared to the middle zone, which was used throughout the current study, the superficial zone is even more vulnerable to the compressive mechanical injury, showing more matrix disruption and GAG loss [43]. Therefore, following traumatic joint injury and the associated damage to cartilage, changes in the uptake of Fab or similarly-sized molecules into the superficial zone may be even more significant than that in the middle zone.

TNFα treatment combined with mechanical injury further increased uptake of Fab, suggesting that the inflammatory response following joint injury can play a critical role in altering the transport properties of damaged cartilage. It is well known that GAG density plays a major role in restricting the penetration of large solutes, such as Fab fragments (48 kDa). Cytokine treatment of bovine cartilage disks resulted in increased GAG release, and the highest GAG loss was caused by the combination of mechanical injury and cytokine insult, as previously reported [11]. Thus, the observed increase in Fab uptake due to injury plus cytokine treatment (Fig. 5) is likely due to the combined increase in tissue hydration and decrease in GAG density. These findings are consistent with several previous reports regarding the effects of zonal GAG density, enzymatic digestion, and static compression showed significant changes in the solute transport of large molecules, such as serum albumin (69 kDa), transferrin (76 kDa), and dextrans (40 kDa and 70 kDa) [6, 14, 44].

The in vitro injury model used in the present study was established to characterize and understand the effects of cartilage injury as a risk factor for cartilage degradation, relevant to the progression of OA [11, 22]. Using the same model, Sui et al. showed that anti-IL-6 Fab fragments significantly reduced the aggrecan degradation induced by mechanical injury and TNFα [11], suggesting that an anti-cytokine strategy could potentially be applied to treatment of joint trauma and the risk of post traumatic OA. Here we quantified the transport of an anti-IL-6 Fab fragment into cartilage to test the practical use of Fab as a therapeutic against intratissue targets.

In addition, Sui et al. [11] showed that the mechanical injury potentiated aggrecan catabolism mediated by TNFα and IL-6/sIL-6R, and hypothesized that altered transport associated with injury could facilitate entry of inflammatory cytokines and proteases involved in cartilage degradation. Although the transport of TNFα, IL-6, and other inflammatory mediators was not studied in the present work, the results of this study indeed support the importance of transport in the kinetics of catabolic processes following cartilage damage caused by traumatic joint injury. If the solute(s) of interest interacts with specific binding sites within the cartilage, changes in transport kinetics after the joint injury would be further affected by solute-matrix binding, since the distribution of such sites could also undergo significant change.

Penetration of Fab fragments into damaged cartilage subjected to mechanical injury and TNFα was measured under 10% static compression, which only allowed transport of 125I-Fab into cartilage disks in the radial direction (as depicted in Fig. 5), whereas transport into free-swelling disks (Figs. 1–4) allowed diffusion in both radial and axial directions. Leddy et al. used 3 kDa and 500 kDa dextrans to study the possibility of anisotropic diffusion in porcine cartilage mediated by collagen fibril orientation [45]; however, they found no such diffusion anisotropy in the middle zone in which collagen is randomly oriented. These results suggest that in our middle zone bovine specimens, diffusion would be similar in the radial and axial directions.

In summary, this study validates for the first time the transport into cartilage of Fab fragments as a putative molecular therapy, in this case against IL-6. Fab can penetrate and diffuse into cartilage, overcoming the limited usefulness of mAb in treating targets fully within cartilage tissue (e.g., molecules, cell receptors, etc.). Uptake of such therapeutics would likely be affected by joint injury and the associated inflammatory response, leading to the entry of catabolic cytokines into cartilage from the synovium and other surrounding joint tissues. Although our study of the effects of injury and cytokines on transport was limited to the 48 kDa Fab fragment, it is possible to predict that the transport of other similarly-sized proteins, including growth factors, cytokines, and matrix molecules, would be affected by similar traumatic injury to cartilage. Therefore, the present study suggests that mechanical injury and inflammatory cytokines could further affect cellular activities via altering transport properties of cartilage matrix, since cell metabolism relies on various solutes that diffuse through the tissue. We suggest that therapeutics against specific molecular targets using smaller-sized molecules such as Fab fragments could be more efficacious than full-size mAb in limiting cartilage degradation caused by traumatic joint injury, due to the ability of Fab fragments to fully penetrate cartilage.

Supplementary Material

We validated the transport of Fab fragments into cartilage as a putative therapy.

Fab fragments against IL-6 can penetrate into and throughout cartilage tissue.

Binding of anti-IL-6 Fab fragments to sites in cartilage matrix was negligible.

Mechanical injury of cartilage tissue increased the uptake of Fab fragments.

TNFα treatment combined with mechanical injury further increased the uptake of Fab.

Acknowledgements

Funded by NIH/NIAMS grant AR45779 and a grant from Janssen Research & Development.

Abbreviations

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α;

- IL-6

interleukin-6;

- ECM

extracellular matrix;

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan;

- OA

osteoarthritis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. References

- 1.Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, et al. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;7:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramson SB, Yazici Y. Biologics in development for rheumatoid arthritis: relevance to osteoarthritis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:212–25. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Vollenhoven RF. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: state of the art 2009. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:531–41. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Z, Bouman-Thio E, Comisar C, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of a human anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody (sirukumab) in healthy subjects in a first-in-human study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:270–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerwin N, Hops C, Lucke A. Intraarticular drug delivery in osteoarthritis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:226–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maroudas A. Transport of solutes through cartilage: permeability to large molecules. J Anat. 1976;122:335–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urech DM, Feige U, Ewert S, et al. Anti-inflammatory and cartilage-protecting effects of an intra-articularly injected anti-TNF{alpha} single-chain Fv antibody (ESBA105) designed for local therapeutic use. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:443–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maroudas A. Distribution and diffusion of solutes in articular cartilage. Biophys J. 1970;10:365–79. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(70)86307-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn TM, Kocian P, Meister JJ. Static compression is associated with decreased diffusivity of dextrans in cartilage explants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:327–34. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leddy HA, Guilak F. Site-specific molecular diffusion in articular cartilage measured using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:753–60. doi: 10.1114/1.1581879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sui Y, Lee JH, DiMicco MA, et al. Mechanical injury potentiates proteoglycan catabolism induced by interleukin-6 with soluble interleukin-6 receptor and tumor necrosis factor alpha in immature bovine and adult human articular cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2985–96. doi: 10.1002/art.24857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia AM, Szasz N, Trippel SB, et al. Transport and binding of insulin-like growth factor I through articular cartilage. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;415:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biswal S, Resnick DL, Hoffman JM, et al. Molecular imaging: integration of molecular imaging into the musculoskeletal imaging practice. Radiology. 2007;244:651–71. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443060295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torzilli PA, Arduino JM, Gregory JD, et al. Effect of proteoglycan removal on solute mobility in articular cartilage. J Biomech. 1997;30:895–902. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank EH, Grodzinsky AJ, Koob TJ, et al. Streaming potentials: a sensitive index of enzymatic degradation in articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1987;5:497–508. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burstein D, Gray ML, Hartman AL, et al. Diffusion of small solutes in cartilage as measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and imaging. J Orthop Res. 1993;11:465–78. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foy BD, Blake J. Diffusion of paramagnetically labeled proteins in cartilage: enhancement of the 1-D NMR imaging technique. J Magn Reson. 2001;148:126–34. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Y, Farquhar T, Burton-Wurster N, et al. Self-diffusion monitors degraded cartilage. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;323:323–8. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.9958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson DL, Urban WP, Jr., Caborn DN, et al. Articular cartilage changes seen with magnetic resonance imaging-detected bone bruises associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:409–14. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260031101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loening AM, James IE, Levenston ME, et al. Injurious mechanical compression of bovine articular cartilage induces chondrocyte apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381:205–12. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurz B, Jin M, Patwari P, et al. Biosynthetic response and mechanical properties of articular cartilage after injurious compression. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:1140–6. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patwari P, Cook MN, DiMicco MA, et al. Proteoglycan degradation after injurious compression of bovine and human articular cartilage in vitro: interaction with exogenous cytokines. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1292–301. doi: 10.1002/art.10892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiMicco MA, Patwari P, Siparsky PN, et al. Mechanisms and kinetics of glycosaminoglycan release following in vitro cartilage injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:840–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurz B, Lemke AK, Fay J, et al. Pathomechanisms of cartilage destruction by mechanical injury. Ann Anat. 2005;187:473–85. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Fitzgerald JB, Dimicco MA, et al. Mechanical injury of cartilage explants causes specific time-dependent changes in chondrocyte gene expression. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2386–95. doi: 10.1002/art.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens AL, Wishnok JS, White FM, et al. Mechanical injury and cytokines cause loss of cartilage integrity and upregulate proteins associated with catabolism, immunity, inflammation, and repair. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1475–89. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800181-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sah RL, Kim YJ, Doong JY, et al. Biosynthetic response of cartilage explants to dynamic compression. J Orthop Res. 1989;7:619–36. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muehleman C, Bareither D, Huch K, et al. Prevalence of degenerative morphological changes in the joints of the lower extremity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(97)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byun S, Tortorella MD, Malfait AM, et al. Transport and equilibrium uptake of a peptide inhibitor of PACE4 into articular cartilage is dominated by electrostatic interactions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;499:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia AM, Lark MW, Trippel SB, et al. Transport of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 through cartilage: contributions of fluid flow and electrical migration. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:734–42. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buschmann MD, Maurer AM, Berger E, et al. A method of quantitative autoradiography for the spatial localization of proteoglycan synthesis rates in cartilage. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:423–31. doi: 10.1177/44.5.8627000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank EH, Jin M, Loening AM, et al. A versatile shear and compression apparatus for mechanical stimulation of tissue culture explants. J Biomech. 2000;33:1523–7. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moeini M, Quinn TM. Solute adsorption to surfaces of articular cartilage explants: apparent versus actual partition coefficients. Soft Matter. 2012;8:11880–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhakta NR, Garcia AM, Frank EH, et al. The insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) I and II bind to articular cartilage via the IGF-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5860–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia AM, Frank EH, Grimshaw PE, et al. Contributions of fluid convection and electrical migration to transport in cartilage: relevance to loading. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;333:317–25. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basser PJ, Schneiderman R, Bank RA, et al. Mechanical properties of the collagen network in human articular cartilage as measured by osmotic stress technique. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;351:207–19. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irie K, Uchiyama E, Iwaso H. Intraarticular inflammatory cytokines in acute anterior cruciate ligament injured knee. Knee. 2003;10:93–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(02)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owen SG, Francis HW, Roberts MS. Disappearance kinetics of solutes from synovial fluid after intra-articular injection. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1994;38:349–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simkin PA, Nilson KL. Trans-synovial exchange of large and small molecules. Clin Rheum Dis. 1981;7:99–129. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller RE, Grodzinsky AJ, Cummings K, et al. Intraarticular injection of heparin-binding insulin-like growth factor 1 sustains delivery of insulin-like growth factor 1 to cartilage through binding to chondroitin sulfate. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010;62:3686–94. doi: 10.1002/art.27709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torzilli PA. Effects of temperature, concentration and articular surface removal on transient solute diffusion in articular cartilage. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1993;31(Suppl):S93–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02446656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maroudas AI. Balance between swelling pressure and collagen tension in normal and degenerate cartilage. Nature. 1976;260:808–9. doi: 10.1038/260808a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rolauffs B, Muehleman C, Li J, et al. Vulnerability of the superficial zone of immature articular cartilage to compressive injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3016–27. doi: 10.1002/art.27610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinn TM, Morel V, Meister JJ. Static compression of articular cartilage can reduce solute diffusivity and partitioning: implications for the chondrocyte biological response. J Biomech. 2001;34:1463–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leddy HA, Haider MA, Guilak F. Diffusional anisotropy in collagenous tissues: fluorescence imaging of continuous point photobleaching. Biophysical journal. 2006;91:311–6. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.