Abstract

Objective

Negative inferential style and deficits in emotional clarity have been identified as vulnerability factors for depression in adolescence, particularly when individuals experience high levels of life stress. However, previous research has not integrated these characteristics when evaluating vulnerability to depression.

Method

In the present study, a racially-diverse community sample of 256 early adolescents (ages 12 and 13) completed a baseline visit and a follow-up visit nine months later. Inferential style, emotional clarity, and depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline, and intervening life events and depressive symptoms were assessed at follow-up.

Results

Hierarchical linear regressions indicated that there was a significant three-way interaction between adolescents’ weakest-link negative inferential style, emotional clarity, and intervening life stress predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for initial depressive symptoms. Adolescents with low emotional clarity and high negative inferential styles experienced the greatest increases in depressive symptoms following life stress. Emotional clarity buffered against the impact of life stress on depressive symptoms among adolescents with negative inferential styles. Similarly, negative inferential styles exacerbated the impact of life stress on depressive symptoms among adolescents with low emotional clarity.

Conclusions

These results provide evidence of the utility of integrating inferential style and emotional clarity as constructs of vulnerability in combination with life stress in the identification of adolescents at risk for depression. They also suggest the enhancement of emotional clarity as a potential intervention technique to protect against the effects of negative inferential styles and life stress on depression in early adolescence.

Keywords: Negative Cognitive Style, Emotional Clarity, Stress, Vulnerability, Depression

Adolescence is an important developmental phase during which the prevalence of depression increases dramatically, with debilitating consequences (Avenevoli, Knight, Kessler, & Merikangas, 2008). It is also the period in which the gender difference in depression emerges, with girls becoming more than twice as likely as boys to experience an episode of depression (Hankin et al., 1998). Additionally, research has indicated that subthreshold depression is associated with substantial functional impairment among adolescents (Gonzáles-Tejera et al., 2005), and that subclinical depressive symptoms in adolescence predict the onset of major depression in adulthood (e.g., van Lang et al., 2007). Life stress has been shown to confer proximal risk for depression (Monroe, Slavich, & Georgiades, 2009), and levels of stress increase during adolescence (Ge et al., 1994), which may help to explain the increase in rates of depression during this developmental period (Hankin & Abramson, 2001). Thus, given the high prevalence and burden of depression, it is important to examine factors that may confer vulnerability to and resilience against depressive symptoms in adolescents, particularly in the context of life stress.

One theory that has been used to examine risk for depression is learned helplessness theory, which proposes that individuals who make internal (“it’s my fault”), stable (“it’s always going to happen”), and global (“it will affect everything in my life”) attributions about the causes of negative events are at greater risk for depression than are individuals who make external, unstable, and specific attributions about negative events (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). More recently, the hopelessness theory of depression has suggested that individuals who attribute negative events to stable and global causes, and who infer negative consequences (“other bad things will happen to me”) and negative self-characteristics (“there’s something wrong with me”) are hypothesized to be at increased risk for experiencing hopelessness, and in turn, depression (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989).

Negative inferential styles, or the tendency to make internal, stable, and global attributions about the causes of negative life events as well as to infer negative consequences and self-characteristics, are thought to consolidate into a trait-like set of interrelated domains that reflect stable individual differences during adolescence, thereby increasing vulnerability to depression during this period (e.g., Cole et al., 2008; Gibb & Alloy, 2006; Hankin, 2008; Turner & Cole, 1994). Once consolidated, negative inferential styles may predict depressive symptoms alone, but should be particularly likely to predict depressive symptoms when experienced in combination with life stressors (e.g., Cole et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1992). Indeed, numerous prospective studies of adolescents have found that inferential styles predict increases in depressive symptoms specifically among adolescents who experience high levels of life stressors (e.g., Abela & McGirr, 2007; Gibb & Alloy, 2006; Hankin, Abramson, Miller, & Haeffel, 2004; Hankin, Abramson, & Siler, 2001; Hilsman & Garber, 1995; Lau & Eley, 2008; Lee, Hankin, & Mermelstein, 2010; for a review, see Abela & Hankin, 2008).

However, prior to consolidation during adolescence, inferential styles may be less internally consistent and stable (Abela & Hankin, 2008). Researchers have suggested that negative inferential styles may only emerge as vulnerabilities to depression during the transition from middle childhood to early adolescence, when children develop the capacity to engage in abstract reasoning and formal operational thought (Turner & Cole, 1994; Weitlauf & Cole, in press). Indeed, although research examining the hopelessness theory among adults has not found inferential styles about causes, consequences, and the self to be empirically distinguishable (Abela, 2002; Hankin et al., 2007; Metalsky & Joiner, 1992), research has suggested that among children, negative inferential styles in different domains are relatively independent of one another (Abela, 2001; Abela & Payne, 2003; Abela & Sarin, 2002; Hankin et al., 2007; Joiner & Rudd, 1996).

Given that inferential styles in childhood and early adolescence may not be fully consolidated (Abela & Hankin, 2008; Cole et al., 2008), Abela and Sarin (2002) suggested that the “weakest link” (the most negative of a youth’s inferential style dimensions) may be the best marker of vulnerability to depression during these periods. According to Abela and Sarin (2002), hopelessness theory suggests that negative inferences about negative events should increase the probability of developing depression, regardless of whether these inferences are about the self, or about the causes or consequences of negative events. Consistent with this proposal, in a sample of early adolescents, Abela and Sarin (2002) found that individuals’ weakest links, but not their inferential styles on any specific domain, interacted with negative events to predict prospective increases in depressive symptoms. Since this initial evaluation, several additional studies of children and adolescents (e.g., Abela & McGirr, 2007; Abela, McGirr & Skitch, 2007; Abela & Payne, 2003) have found similar support for conceptualizing inferential style from the perspective of the weakest link.

In addition to inferential styles, recent work has identified deficits in emotional clarity (EC) as a risk factor for depression. A component of emotional intelligence, EC is characterized by awareness and understanding of one’s own emotions and emotional experiences, as well as the ability to properly label them (Gohm & Clore, 2000). It is hypothesized that the ability to perceive and discriminate among one’s own emotions allows for the allocation of resources toward goal-oriented thoughts and behavior rather than toward directing efforts towards understanding one’s own emotional experiences (Gohm & Clore, 2000). Indeed, among adults, lower levels of EC have been linked to less adaptive coping and less positive well-being (Gohm & Clore, 2000), as well as to less adaptive problem-solving behavior and poorer performance with complex problems compared to individuals with higher EC (Otto & Lantermann, 2006). Among older adults, higher EC also has been shown to protect against depressive symptoms caused by the stress of chronic pain (Kennedy et al., 2010). Among children, lower EC has been shown to predict depressive symptoms over time (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010). Only a few studies have evaluated EC in relation to psychological adjustment in samples of adolescents. Among adolescents, lower EC has been associated with higher perceived stress, anxiety, and less life satisfaction (Extremera & Fernandez-Berrocal, 2005; Fernandez-Berrocal, Alcaide, Extremera, & Pizarro, 2006). Additionally, one study of late adolescents found that higher EC buffered against the impact of several types of negative cognitive styles (dysfunctional attitudes, self-criticism, and neediness) on prospective increases in depressive symptoms (Stange et al., in press). Thus, there is evidence that higher EC may protect against the negative impact of cognitive styles and stress on symptoms of depression, whereas lower EC may exacerbate symptoms of depression. However, it is unclear whether low EC can meaningfully be viewed as a vulnerability to depression from within a vulnerability-stress perspective during adolescence. To date, no studies have prospectively evaluated EC as a protective factor against depression in early adolescence, particularly in the context of life stressors.

Given that negative inferential style and EC both have been identified as risk factors for depression, it is surprising that little research to date has evaluated their relationship to each other. To our knowledge, only one study has evaluated the association between EC and inferential styles. In a sample of adults, Gohm and Clore (2000) found that EC was positively correlated with inferential style for positive events, but was not significantly correlated with inferential style for negative events. Accordingly, individuals with high EC may tend to make positive, self-affirming inferences about the causes of good events, but may exhibit variety in their inferential styles for negative or stressful events.

However, developmental scientists traditionally have examined cognition and emotion separately (e.g., Calkins & Bell, 2010), and little is known about specific cognition-emotion interactions that contribute to depression during adolescence. For instance, one line of research has shown that inferential styles develop and continue to consolidate through early adolescence (Abela & Hankin, 2008) as they are shaped by life experiences (Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb, & Neeren, 2006; Gibb et al., 2006; Hankin et al., 2009). A second line of research reveals the emergence of emotional competence, broadly speaking, during childhood as children acquire the ability to differentiate emotions in themselves and others, and to understand the causes and consequences of emotions (e.g., Saarni, 1991). Notably, emotional clarity represents a fundamental component of emotional competence; indeed, empirical findings demonstrate the existence of individual differences in emotional clarity as early as third grade (i.e., age 8–10 years). Thus, although emotional clarity may precede the consolidation of inferential styles, the interactive contribution of negative inferential style and low emotional clarity to depression may become increasingly pronounced during the transition to adolescence.

In regards to the specific nature of this interaction, individuals with negative inferential styles are more likely to make negative inferences for stressful events, leading them to become dysphoric. If they also have low EC, they may not be able to clearly understand their emotional reactions to the stressful events and will have to focus attention on their dysphoria to try to understand it. Increased attention to the dysphoria and lack of clarity about it should worsen the dysphoria, leading to more severe and persistent dysphoric mood as well as a greater likelihood of becoming depressed. Thus, low EC may lead to greater attentional focus and rumination on the dysphoria brought about by negative inferences for stressors (e.g., Ciesla & Roberts, 2007).

Finally, although negative inferential style and EC have been established as vulnerabilities to depression, no work to date has integrated these characteristics when evaluating which adolescents may be most at risk for depression. Insight into one’s emotions is likely helpful, if not necessary, for the utilization of appropriate coping strategies (Gohm & Clore, 2000), which may be particularly useful among individuals vulnerable to experiencing depressed mood. For example, although negative inferential styles confer vulnerability to depression, it is possible that having high EC protects against the impact of negative inferential styles on depression; better awareness of one’s emotions could allow for more adaptive coping or superior problem-solving strategies, even if one generates negative inferences about the causes of negative events. An individual with a negative inferential style who experiences negative events is likely to experience dysphoric mood, but if she can recognize her feelings of sadness, she may be able to engage in strategies such as distraction (thus reducing her negative thoughts about the causes and consequences of the event) or problem-solving (thus potentially improving the outcome of the negative event), either of which is likely to improve her mood. In contrast, the impact of negative inferential styles on depressed mood may be more severe if individuals have low EC and are unable to cope well with stress or the associated negative affect (e.g., one might become stuck in a cycle of negative thoughts about the causes and consequences of the event and spiral into depression; e.g., Ciesla & Roberts, 2007). Hence, the combination of negative inferential styles and low EC may confer particularly high levels of vulnerability to depressed mood following life stress. Thus, identifying low EC as an additional vulnerability factor for depression among adolescents with negative inferential styles has the potential to have significant implications for prevention and treatment programs. However, to date, no longitudinal studies of adolescents have investigated EC and inferential styles together as predictors of depression in the context of life stress.

In the present study, we prospectively evaluated predictors of depressive symptoms among a sample of early adolescents just prior to the age of greatest risk of first onset of depression. We sought to integrate previous models of depression by evaluating whether inferential styles and emotional clarity would interact to predict prospective changes in depressive symptoms among adolescents who experienced life stress. Specifically, we hypothesized that high EC would buffer against the impact of life stress among adolescents with more negative inferential styles. Similarly, we hypothesized that negative inferential styles would exacerbate the impact of life stress on depressive symptoms among adolescents with lower EC. Thus, we expected adolescents to be most vulnerable to experiencing depression following life stress if they had negative inferential styles in combination with low EC.

Method

Participants

Sample recruitment

The current sample was part of a study intended to evaluate racial and gender differences in the development of depression among Caucasian and African-American adolescents (Alloy et al., 2012). Caucasian and African-American adolescents between the ages of 12 and 13, and their mothers or primary female caregivers, were recruited from Philadelphia area public and private middle schools. Participants were recruited in two primary ways. First, with the permission of the Philadelphia School District (PSD), we mailed a letter of introduction and description of the study to parents of students attending some schools in the PSD. Because the study was designed to have equal proportions of Caucasian and African American adolescents, schools were selected partly to achieve this racial representation. Caregivers could call or return a prepaid postcard indicating their interest in the study, but most families were recruited through follow-up phone calls from project staff inviting female caregivers and their adolescent children to participate (approximately 68% of the sample). Second, advertisements describing the study were placed in Philadelphia area newspapers and caregivers (32% of the sample) called in to indicate their interest.

Mothers (93.7% of caregivers were the mothers of the adolescents) interested in participating with their adolescent children completed a screening instrument over the phone to determine eligibility. Adolescents were eligible for the study if they were 12 or 13 years old; self-identified as Caucasian/White, African-American/Black or Biracial (adolescents could be Hispanic or non-Hispanic as long as they also identified as White or Black); and the primary female caregiver was also willing to participate. Adolescents were ineligible for the study if there was no mother/primary female caregiver available to participate; either the adolescent or caregiver did not read or speak English well enough to be able to complete the study assessments; or either the adolescent or caregiver was mentally retarded, had a severe developmental disorder (e.g., autism), had a severe learning disability or other cognitive impairment, was psychotic, or exhibited any other medical or psychiatric problem that would prevent either of them from completing the study assessments.

Study sample

The sample for this study includes 256 adolescents (Mean = 12.32 years old; SD = 0.61) and their mothers/female caregivers who completed at least the baseline assessments and one follow-up assessment. The study sample was 54% female, 51% African American, and 2.3% Hispanic. The families exhibited a range of socioeconomic status levels, with 24.1% of participants falling below $30,000 annual family income, 35.4% falling between $30,000 – $59,999, 17.2% falling between $60,000 – $89,999, and 23.3% falling above $90,000. Fifty-two percent of the sample was eligible for free lunch at school. An original sample of 292 families completed the baseline study visits, but 36 families declined further participation and did not complete a follow-up visit, resulting in the current sample of 256 adolescents (an 88% retention rate). Adolescents who completed a follow-up visit had lower levels of depressive symptoms at Time 1 (t = 2.32, p = .02) and were less likely to be Caucasian (χ2 = 5.37, p = .02), but did not differ on any other demographic characteristics or study variables.

Procedures

Adolescents completed a baseline session lasting between 2–3 hours at which measures of depressive symptoms, negative inferential styles, and emotional clarity were completed. At a follow-up visit approximately 9 months later (Mean = 264 days; SD = 95 days), adolescents completed measures of depressive symptoms, and adolescents and their mothers completed a measure of life events that had occurred to the adolescent since the first baseline visit.

Measures

Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is a widely used self-report measure assessing depressive symptoms in youth. It is designed for use with youth of ages 7–17 and consists of 27 items that reflect affective, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of depression. Items are rated on a 0–2 scale and are summed for a total depression score, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Scores range from 0 to 54 and scores ≥ 13 are considered clinically significant (Kovacs, 1985). The CDI has good reliability and validity as a measure of depressive symptoms (Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005). Internal consistency in this sample was α = .86 at baseline and .80 at follow-up.

Inferential Styles

The Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire-Modified (ACSQ-M; Alloy et al., 2012) is a modified version of the original ACSQ (Hankin & Abramson, 2002) that assesses inferential styles regarding the internality (“was it caused by something about you or something else?”), stability (“will it cause [the same event] to happen in the future?”), and globality (“will it cause problems in other parts of your life?”) of causes, as well as the consequences (“will other bad things happen to you in the future because of [the event]?”) and self-worth implications (“Is there something wrong with you because of [the event]?”), of negative life events. The original ACSQ assessed inferential styles for negative events in the achievement and interpersonal domains, whereas the ACSQ-M also assesses inferential styles in the appearance domain, another content area that is of importance to adolescents. Adolescents are presented with 12 hypothetical negative events in the achievement, interpersonal, or appearance domains (4 events per domain) and are asked to make inferences about the causes (internal-external, stable-unstable, and global-specific), consequences, and self-worth implications of each event. Each dimension is rated from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating a more negative inferential style, and dimension scores range from 12 to 60. Because we studied a sample of early adolescents, we used each adolescent’s weakest link on the ACSQ (his/her most negative dimension of inferential style) in our analyses. Although some studies have averaged the causality dimensions prior to calculating the weakest link, we reasoned that an adolescent’s most negative inferential style should be the best predictor of his/her vulnerability to depression, regardless of whether the inferential style was about the causes, self, or consequences of an event. The ACSQ has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, good retest reliability, and adequate factor structure among adolescents (Alloy et al., 2012; Hankin & Abramson, 2002). Internal consistencies in this sample were α = .79 – .88 for the 5 individual dimensions.

Emotional Clarity

The Emotional Clarity Questionnaire (ECQ; Flynn & Rudolph, 2010) is a measure adapted for children from an instrument used with adults (TMMS; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995) that assesses perceived emotional clarity. The ECQ is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that asks children to rate the way they experience their feelings (e.g., “I usually know how I am feeling,” “My feelings usually make sense to me,” and “I am often confused about my feelings” [reverse scored]) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Item scores are summed with higher scores indicating greater levels of emotional clarity. Scores range from 5 to 35. The ECQ has demonstrated good internal consistency, and convergent validity has been established through significant correlations with behavioral measures assessing overlapping emotion processing capabilities, specifically the identification of affective information presented via facial expressions (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010). In the current study, the EC demonstrated good internal consistency, α = .82.

Life Events

Life events were evaluated with the Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire (ALEQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002), which is designed to assess the occurrence of a broad range of negative or stressful events often reported by adolescents, including familial, social, relationship, appearance-related, and school/achievement events. Adolescents and their mothers completed separate versions of the 63-item ALEQ and indicated events that occurred to the adolescent since the baseline assessment. Following completion of the ALEQ, adolescents completed the Life Events Interview (LEI; Safford, Alloy, Abramson, & Crossfield, 2007) with trained interviewers who objectively evaluated whether events endorsed by the adolescents and/or their mothers on the ALEQ met a priori event definition criteria. Any events that did not meet the stringent criteria were disqualified, thus reducing any problems related to subjective report biases. For example, for the event “a close family member died,” interviewers verified that the family member was a member of the immediate family or was very close with (e.g., frequently communicated with) the adolescent; for the event “did poorly on, or failed, a test or class project,” interviewers verified that the adolescent received a grade of C- or less. Interviewers also verified that events occurred within the timeframe since the baseline study visit and obtained frequencies of the occurrence of each event. In the original development of the a priori event definition criteria for the LEI, life event items were discussed at weekly research team meetings and a final consensus decision was made on the occurrence and rating of the events (Safford et al., 2007). The process used was similar to the consensus ratings commonly used in other interview-based (Brown & Harris, 1978) life events research. Reliability and validity have been established for the ALEQ (e.g., Hankin, 2008; Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010) and for the LEI (e.g., Safford et al., 2007; Alloy & Abramson, 1999; Alloy & Clements, 1992) in their ability to accurately capture the life events experienced over a period of time. A composite variable reflecting total number of occurrences of negative life events was used for the analyses in the present study.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Each adolescent’s weakest link inferential style score was equal to the most negative of his or her domains on the ACSQ, which were distributed as follows: internal (84.8%), stable (7.4%), global (5.1%), consequences (1.2%), and self (1.6%). This distribution of weakest links across ACSQ domains appeared to be attributable to the fact that adolescents had higher scores on the internal domain relative to the other domains, as follows: internal (Mean = 47.45, SD = 13.18), stable (Mean = 33.59, SD = 11.76), global (Mean = 31.12, SD = 11.61), consequences (Mean = 25.85, SD = 10.36), and self (Mean = 22.70, SD = 13.38).

There were no gender differences in negative inferential styles (t = 0.99, p = .32), EC (t = 0.33, p = .74), life events experienced (t = −0.57, p = .57), or depressive symptoms at baseline (t = −1.15, p = .25). However, girls had higher levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up (t = −2.40, p = .02); therefore, gender was included as a covariate in prospective analyses. African American adolescents had higher levels of EC (t = −2.03, p = .04) and marginally less negative weakest link inferential styles (t = 1.90, p = .06). There were no racial differences in life events experienced (t = 1.53, p = .13), or in depressive symptoms at baseline (t = −0.35, p = .73) or follow-up (t = 0.10, p = .92). Additionally, children with lower socioeconomic status (as indexed by eligibility for free lunch) experienced more stressful events (t = 2.11, p = .04). Depressive symptoms were relatively low in our sample at both time points (see Table 1); 41.4% of the sample experienced increases in depressive symptoms at follow-up. Bivariate correlations are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Measure | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| CDI (Baseline) | 6.39 | 5.93 |

| CDI (Follow-Up) | 4.96 | 4.82 |

| ACSQ Weakest Link | 48.46 | 12.44 |

| Emotional Clarity | 25.01 | 4.09 |

| Life Events | 57.82 | 69.13 |

Note. CDI = Child Depression Inventory; ACSQ = Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Correlations between Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDI (Baseline) | --- | .60*** | .13* | −.34*** | .19** |

| 2. CDI (Follow-Up) | --- | .23*** | −.26*** | .34*** | |

| 3. ACSQ Weakest Link | --- | −.05 | .14* | ||

| 4. Emotional Clarity | --- | −.07 | |||

| 5. Life Events | --- |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Note. CDI = Child Depression Inventory; ACSQ = Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire.

Prospective Analyses

To evaluate whether inferential styles, EC, and life stress would interact to predict depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for initial depressive symptoms, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions. Continuous predictor variables were centered at their means prior to analysis (Aiken & West, 1991). To test our hypotheses, we regressed follow-up CDI scores on a number of predictor variables (see Table 3). In Step 1, baseline CDI scores and gender were entered, thus creating a residual score reflecting change in depressive symptoms from baseline to follow-up. In Step 2, we entered main effects of inferential style weakest link, EC, and life events. In Step 3, the two-way interaction terms between each of the three main effect variables were entered. Finally, in Step 4, the three-way interaction term between inferential style weakest link, EC, and life events was entered.

Table 3.

Three-Way Interaction between Emotional Clarity, Inferential Style Weakest Link, and Life Events Predicting Depressive Symptoms at Follow-Up, Controlling for Baseline Depressive Symptoms

| Step | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CDI (Baseline) | .49 | 9.50*** | .37*** |

| Gender | .10 | 2.06* | ||

| 2 | Emotional Clarity (EC) | −.03 | −0.57 | .07*** |

| Inferential Style Weakest Link (ACSQ) | .14 | 2.92** | ||

| Life Events (LE) | .20 | 4.15*** | ||

| 3 | EC x LE | −.03 | −0.63 | .01 |

| ACSQ x LE | .05 | 1.11 | ||

| EC x ACSQ | −.07 | −1.43 | ||

| 4 | EC x ACSQ x LE | −.15 | −2.89** | .02** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Note. CDI = Child Depression Inventory. Gender is coded as Male = 0, Female = 1.

All significant effects remain significant when not controlling for gender.

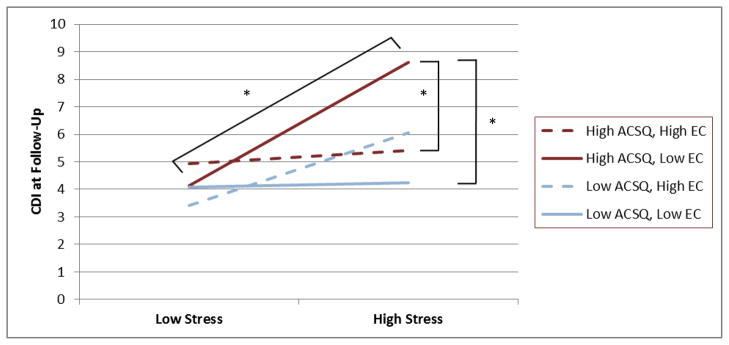

A significant three-way interaction emerged between inferential style, EC, and life events predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up (Table 3; Figure 1)1. To probe the form of this three-way interaction, we tested for lower-order effects using the commonly-accepted a priori-defined cutoffs of one standard deviation above and below the mean of each continuous predictor variable (Aiken & West, 1991) (for means and standard deviations, see Table 1). As hypothesized, among adolescents with higher EC, there was not a significant interaction between inferential style and life events, t = −1.62, p = .11. However, among adolescents with lower EC, there was a significant two-way interaction between inferential style and life events, t = 2.64, p < .01, such that life events predicted increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents with more negative inferential styles, t = 4.35, p < .0001, but not among adolescents with less negative inferential styles, t < 0.01, p > .99. Similarly, among adolescents with lower EC, negative inferential style predicted increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents who experienced higher levels of negative life events, t = 3.84, p < .001, but not among adolescents who experienced lower levels of life events, t = −0.08, p = .94. Additionally, among adolescents with more negative inferential styles, there was a significant two-way interaction between EC and life events, t = −2.70, p < .01, such that lower EC predicted increases in depressive symptoms when adolescents experienced higher levels of negative life events, t = −3.26, p = .001, but not when adolescents experienced lower levels of life events, t = 0.78, p = .44. However, among adolescents with less negative inferential styles, there was not a significant interaction between EC and life events, t = 1.62, p = .11. Thus, higher EC appeared to buffer against the impact of negative life events on depressive symptoms among adolescents with negative inferential styles, whereas lower EC exacerbated the impact of life events on depressive symptoms. In other words, adolescents with more negative inferential styles in combination with lower EC were most vulnerable to experiencing increases in depressive symptoms following life stress. The incremental effect size of the three-way interaction was small-to-medium (f2 = .03).

Figure 1.

Three-way interaction between inferential style weakest link (ACSQ), emotional clarity (EC), and life stress predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for initial depressive symptoms. * p < .05.

Discussion

The results of the present study support an integrated model of risk factors for depression among early adolescents. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that negative inferential styles conferred risk for depression, and low EC further exacerbated this risk for depression, among adolescents who encountered higher levels of life stress. Specifically, adolescents with low emotional clarity and high negative inferential style weakest links experienced the greatest increases in depressive symptoms following life stress. We found evidence for a vulnerability-stress interaction between negative inferential styles and life events predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up, but only among adolescents with lower EC. Similarly, there was also evidence for an interaction between EC and life events predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up, but only among adolescents with more negative inferential style weakest links. Thus, when adolescents experience high levels of stress, the impact of negative inferential styles and EC on depressive symptoms may differ depending on whether one has higher or lower levels of the other construct. Inferential styles and EC may therefore both be important in determining which adolescents are most vulnerable to experiencing increases in depressive symptoms following life stress.

Several findings of the present study are notable. First, life events predicted prospective increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents with more negative inferential style weakest links, consistent with previous studies. However, this interaction was specific to adolescents who had lower EC. This suggests that negative inferential styles may serve as a vulnerability to depression particularly when adolescents have low insight into their emotions. Because few previous studies examining the interaction between negative inferential styles and life events have evaluated protective factors such as high EC, including EC in attributional models of depression could help to explain with more precision which adolescents are most vulnerable to experiencing depression following naturally-occurring stressors, which researchers have noted is an important goal of future research in youth depression (Hankin, 2012). It is likely that having higher EC allows adolescents to regulate their emotions more effectively and to engage in more adaptive coping strategies such as problem-solving. Thus, even if adolescents have a cognitive vulnerability to depression and experience high levels of stress, understanding their emotions may allow them to cope appropriately and to experience sadness as only transient. In contrast, adolescents who have lower EC may spend more time attempting to understand their sadness rather than determining how to actively improve their situation, which may be particularly deleterious when the content of their thoughts is negative and when they are in stressful environments. This suggests that EC may buffer against the effects of negative inferential styles and life stress on depressive symptoms, suggesting a potentially new target for intervention to increase resilience during adolescence.

Although previous research has indicated that lower EC is cross-sectionally associated with psychological maladjustment and history of depression (e.g., Ehring, Fischer, Schnulle, Bosterling, & Tuschen-Caffier, 2008; Extremera, Duran, & Rey, 2007; Fernandez-Berrocal et al., 2006; Hansenne & Bianchi, 2009), as well as associated with increases in depressive symptoms over time (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010), to our knowledge this represents the first study among adolescents that has prospectively evaluated EC as a predictor of depression in the context of life stressors. These results suggest that low EC may serve as a vulnerability to depression when adolescents are confronted with life stress. As noted, however, other factors such as negative inferential styles may indicate when low EC serves as a vulnerability to depression. This study suggests that for adolescents in high-stress environments, it may be helpful to have at least one adaptive characteristic such as higher EC or less negative inferential styles. Indeed, it was only adolescents who had both negative inferential styles and low EC who experienced significant increases in depressive symptoms in the face of life stressors.

This study has several strengths, including the use of a prospective design with a racially and socioeconomically diverse community sample of early adolescents, and the evaluation of EC in the context of life stress. Additionally, life event data were verified via an interview with objective event criteria, which likely reduced the confounding of self-reported life events with other self-report measures used that are also associated with depression (e.g., negative inferential style; Safford et al., 2007).

Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, although we found that high EC buffered against increases in depressive symptoms following life stressors, it is not clear why EC served as a protective factor. Previous research has suggested that high EC may be adaptive because of its association with problem-solving and interpersonal skills, but we did not evaluate the exact mechanisms of its protective effects in the current sample. Additionally, it is unclear why adolescents’ weakest links were so often from the internal domain. Prior studies have not included the internality domain when evaluating the weakest link, so it is unclear whether the weighting of the weakest link toward the internality domain in our sample is unusual. Some studies of adolescents (e.g., Calvete, Villardon, & Estevez, 2008) have found high distributions of the weakest link toward the “implications for the self” domain, which shares some conceptual overlap with the internality domain (which refers to the tendency to explain negative events as being caused by oneself). Adolescents’ tendency to attribute negative events to internal causes could be due to the self-focus that often occurs during adolescence and which has been associated with depressed mood (Baron, 1986; Goossens, Seiffge-Krenke, & Marcoen, 1992). It is possible that negative inferential style in the internal domain thus may begin to consolidate sooner than the other domains that are featured in helplessness and hopelessness theories, and that the internal domain, therefore, was the best predictor of vulnerability to depression in our sample.

Although the present study was prospective in design, it was limited by having only two waves of data, which precluded our ability to use idiographic (within-subject) measurement of variations in stress, which has more consistently supported vulnerability-stress models of depression (Abela & Hankin, 2008; Hankin, 2012). Although we evaluated negative life events, it could also have been useful to evaluate hassles (or ongoing negative conditions), which may play an important role in the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence (e.g., Abela et al., 2012; Pettit et al., 2010). Our study may also have been limited by the use of self-reported inferential styles, EC, and depressive symptoms. However, self-report may be an effective method of evaluating certain subjective experiences about which people may be self-aware, which may include constructs such as these (Haeffel & Howard, 2010). Additionally, although retention of participants was high, Caucasian families and adolescents with higher levels of depressive symptoms were less likely to complete the follow-up visit, which may limit the generalizability of these results.

Although we selected our sample at an age prior to the age of greatest risk of first onset of depression, levels of depressive symptoms in our sample were relatively low at both time points. Future work should seek to replicate these results among older adolescent samples that are becoming more symptomatic. Next, although the figure appears to indicate that adolescents with higher EC and less negative inferential styles (who would be expected to be most resilient against stress) experienced increases in depressive symptoms following stress, we were not able to investigate and interpret this apparent trend because the relevant two-way interactions were not significant. Future replications of this study should examine the effects of stress on symptoms of depression among these adolescents who are hypothesized to be most resilient. Finally, the effect size of the three-way interaction was relatively small, so the clinical significance of these effects is unclear; nevertheless, these results indicate interactive relationships between EC, inferential styles, and life events that are suggestive of potential targets for intervention and prevention of depression in adolescents.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Although programs exist for enhancing resiliency against depression in children and adolescents through the development of adaptive inferential styles (e.g., the Penn Resiliency Program; Brunwasser et al., 2009; Gillham et al., 2008), the results of the current study suggest that prevention programs in early adolescence should also consider helping adolescents to understand their emotions with greater clarity. Future work is needed to determine whether enhancing the ability to understand one’s emotions would serve as a buffer against depression, but these results suggest that understanding one’s feelings may be an important characteristic that determines whether adolescents will develop symptoms of depression in the presence of life stress, particularly among adolescents with negative inferential styles. Research investigating vulnerabilities to depression should consider including EC, as when evaluated in combination with negative inferential styles, it may specify with greater accuracy which individuals are most at risk for experiencing depression. In addition to evaluating predictors of fluctuations in depressive symptoms, future studies should evaluate whether low EC (in combination with inferential styles) contributes to the first onset or recurrence of episodes of major depression in adolescents. In so doing, this work will contribute to understanding the dramatic increase in rates of depression during adolescence.

Footnotes

The two-way interaction between inferential style weakest link and life events was not significant overall (t = 0.04, p = .45), but was significant specifically among adolescents with lower EC as reported above. In contrast, when using the ACSQ total score rather than the weakest link, there was a significant interaction between inferential styles and life events predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up (t = 2.07, p = .04). However, the three-way interaction between ACSQ total score, EC, and life events was not significant (t = −1.16, p = .25), indicating that support for the integrated model was specific to the inferential style weakest link conceptualization of the ACSQ.

Contributor Information

Jonathan P. Stange, Email: jstange@temple.edu, Temple University - Psychology, 1701 N. 13th St. Weiss Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122

Lauren B. Alloy, Email: lalloy@temple.edu, Temple University - Psychology, 1701 N. 13th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122

Megan Flynn, Email: megan-flynn@bethel.edu, Bethel University - Psychology, Arden Hills, Minnesota.

Lyn Y. Abramson, Email: lyabrams@wisc.edu, University of Wisconsin, Madison - Psychology, Madison, Wisconsin

References

- Abela JRZ. The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis–stress and causal mediation components in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:241–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1010333815728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ. Depressive mood reactions to failure in the achievement domain: A test of the integration of the hopelessness and self-esteem theories of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, Sheshko DM, Fishman MB, Stolow D. Multi-wave prospective examination of the stress-reactivity extension of the response styles theory of depression in high-risk children and early adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, McGirr A. A. Operationalizing cognitive vulnerability and stress from the perspective of the hopelessness theory: A multi-wave longitudinal study of children of affectively ill parents. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46(4):377–395. doi: 10.1348/014466507X192023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, McGirr A, Skitch SA. Depressogenic inferential styles, negative events, and depressive symptoms in youth: An attempt to reconcile past inconsistent findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2397–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Payne AVL. A test of the integration of the hopelessness and self-esteem theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:519–535. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Sarin S. Cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression: A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96(2):358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;87(1):49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. The Temple–Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression (CVD) Project: conceptual background, design and methods. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1999;13:227–262. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Smith JM, Gibb BE, Neeren AM. Role of parenting and maltreatment histories in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: Mediation by cognitive vulnerability to depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:23–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Black SK, Young ME, Goldstein KE, Shapero BG, Stange JP, Abramson LY. Cognitive vulnerabilities and depression versus other psychopathology symptoms and diagnoses in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(5):539–560. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.703123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Clements CM. Illusion of control: invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101(2):234–245. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Knight E, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baron P. Egocentrism and depressive symptomatology in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1986;1(4):431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Social Origins of Depression: a Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. Free Press; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Brunwasser SM, Gillham JE, Kim ES. A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program’s effect on depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1042–1054. doi: 10.1037/a0017671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Bell MA. Introduction: Putting the domains of development into perspective. In: Calkins SD, Bell MA, editors. Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition. Washington, DC: APA; 2010. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Villardon L, Estevez A. Attributional style and depressive symptoms in adolescents: An examination of the role of various indicators of cognitive vulnerability. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:944–953. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Rumination, negative cognition, and their interactive effects on depressed mood. Emotion. 2007;7(3):555–565. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Ciesla JA, Dallaire DH, Jacquez FM, Pineda AQ, Lagrange B, Felton JW. Emergence of attributional style and its relation to depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):16–31. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Fischer S, Schnulle J, Bosterling A, Tuschen-Caffier B. Characteristics of emotion regulation in recovered depressed versus never depressed individuals. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44(7):1574–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera N, Duran A, Rey L. Perceived emotional intelligence and disposition optimist-pessimism: Analyzing their role in predicting psychological adjustment among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(6):1069–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera N, Fernandez-Berrocal P. Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: Predictive and incremental validity using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(5):937–948. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Berrocal P, Alcaide R, Extremera N, Pizarro D. The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individual Differences Research. 2006;4(1):16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD. The contribution of deficits in emotional clarity to stress responses and depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychopathology. 1994;30(4):467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:264–274. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Walshaw PD, Comer JS, Shen GHC, Villari AG. Predictors of attributional style change in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:425–439. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Brunwasser SM, Freres DR. Preventing depression in early adolescence: The Penn Resiliency Program. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16(4):495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Tejera G, Canino G, Ramirez R, Chavez L, Shrout P, Bird H, Bauermeister J. Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(8):888–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens L, Seiffge-Krenke I, Marcoen A. The many faces of adolescent egocentrism: Two European replications. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Howard GS. Self-report: Psychology’s four-letter word. American Journal of Psychology. 2010;133:181–188. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.123.2.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Future directions in vulnerability to depression among youth: Integrating risk factors and processes across multiple levels of analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.711708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: a short-term prospective multiwave study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):324–333. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:491–504. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Miller N, Haeffel GJ. Cognitive vulnerability-stress theories of depression: Examining affective specificity in the prediction of depression versus anxiety in three prospective studies. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:309–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Siler M. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in adolescence. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25(5):607–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex dfferences in adolescent depression. Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Oppenheimer C, Jenness J, Barrocas A, Shapero BG, Goldband J. Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: Review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1327–1338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansenne M, Bianchi J. Emotional intelligence and personality in major depression: Trait versus state effects. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsman R, Garber J. A test of the cognitive diathesis-stress model of depression in children: Academic stressors, attributional style, perceived competence, and control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(2):370–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Rudd MD. Toward a categorization of depression-related psychological constructs. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1996;20:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LA, Cohen TR, Panter AT, Devellis BM, Yamanis TJ, Jordan JM, Devellis RF. Buffering against the emotional impact of pain: Mood clarity reduces depressive symptoms in older adults. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:975–987. [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, Olino TM. Toward guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:412–432. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JYF, Eley TC. Attributional style as a risk marker of genetic effects of adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:849–859. doi: 10.1037/a0013943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Hankin BL, Mermelstein RJ. Perceived social competence, negative social interactions, and negative cognitive style predict depressive symptoms during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:603–615. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.501284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metalsky GI, Joiner TE., Jr Vulnerability to depressive symptomatology: A prospective test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components of the hopelessness theory of depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:667–675. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Georgiades K. The social environment and life stress in depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of Depression. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2009. pp. 340–360. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman MEP. Predictors and consequences of childhood depressive symptoms: A fine-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:405–422. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto JH, Lantermann ED. Individual differences in emotional clarity and complex problem solving. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 2006;25(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Yaroslavsky I. Developmental relations between depressive symptoms, minor hassles, and major events from adolescence through age 30 years. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:811–824. doi: 10.1037/a0020980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. Children’s understanding of strategic control of emotional expression in social transactions. In: Harris PL, editor. Children’s understanding of emotion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Crossfield AG. Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: a test of the stress generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99(1–3):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the trait meta-mood scale. In: Pennebaker JW, editor. Emotional, Disclosure, and Health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Boccia AS, Shapero BG, Molz AR, Flynn M, Matt LM, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Emotion regulation characteristics and cognitive vulnerabilities interact to predict depressive symptoms in individuals at risk for bipolar disorder: A prospective behavioral high-risk study. Cognition and Emotion. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.689758. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JE, Jr, Cole DA. Developmental differences in cognitive diatheses for child depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:15–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02169254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lang ND, Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC. Predictors of future depression in early and late adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97(1–3):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitlauf AS, Cole DA. Cognitive development masks support for attributional style models of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9617-8. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]