Abstract

Previous studies showed that fitter yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) that can grow by fermenting glucose in the presence of allyl alcohol, which is oxidized by alcohol dehydrogenase I (ADH1) to toxic acrolein, had mutations in the ADH1 gene that led to decreased ADH activity. These yeast may grow more slowly due to slower reduction of acetaldehyde and a higher NADH/NAD+ ratio, which should decrease the oxidation of allyl alcohol. We determined steady-state kinetic constants for three yeast ADHs with new site-directed substitutions and examined the correlation between catalytic efficiency and growth on selective media of yeast expressing six different ADHs. The H15R substitution (a test for electrostatic effects) is on the surface of ADH and has small effects on the kinetics. The H44R substitution (affecting interactions with the coenzyme pyrophosphate) was previously shown to decrease affinity for coenzymes 2-4-fold and turnover numbers (V/Et) by 4-6-fold. The W82R substitution is distant from the active site, but decreases turnover numbers by 5-6-fold, perhaps by effects on protein dynamics. The E67Q substitution near the catalytic zinc was shown previously to increase the Michaelis constant for acetaldehyde and to decrease turnover for ethanol oxidation. The W54R substitution, in the substrate binding site, increases kinetic constants (K’s, by > 10-fold) while decreasing turnover numbers by 2-7-fold. Growth of yeast expressing the different ADHs on YPD plates (yeast extract, peptone and dextrose) plus antimycin to require fermentation, was positively correlated with the log of catalytic efficiency for the sequential bi reaction (V1/KiaKb = KeqV2/KpKiq, varying over 4 orders of magnitude, adjusted for different levels of ADH expression) in the order: WT H15R > H44R > W82R > E67Q > W54R. Growth on YPD plus 10 mM allyl alcohol was inversely correlated with catalytic efficiency. The fitter yeast are “bradytrophs” (slow growing) because the ADHs have decreased catalytic efficiency.

Keywords: Alcohol dehydrogenase, Kinetics, Mutagenesis, Allyl alcohol, Fitter Yeast

1. Introduction

In a pioneering study of evolution of fitter organisms in the laboratory, Wills and coworkers selected for yeast strains that must grow by fermenting glucose while being exposed to allyl alcohol [1-4]. The yeast require alcohol dehydrogenase I (ADH1, cytoplasmic isoenzyme 1) to reduce acetaldehyde for anaerobic growth (NADH + acetaldehyde == NAD+ + ethanol), but oxidation of allyl alcohol (CH2=CH-CH2 OH) with NAD+ to acrolein (CH2=CH-CHO) catalyzed by ADH is lethal to wild-type yeast. It was originally proposed that the fitter yeast might express an ADH with decreased activity for allyl alcohol due to substitutions of amino acid residues in the active site. However, Wills and coworkers found mutant yeasts had decreased ADH activity for oxidation of ethanol or reduction of acetaldehyde. Many of the mutated ADHs had more positive charge upon electrophoresis at pH 8.6. Decreased ADH activity can be expected to cause slower growth, due to slower reduction of acetaldehyde, and higher NADH/NAD+ levels, which should decrease the rate of oxidation of allyl alcohol and be protective. Changes in redox state in mutant yeasts were observed, but it has not been clear what changes in kinetic constants for the substituted ADHs could account for the altered redox state and the increased fitness [4-6].

Amino acid substitutions were identified by protein sequencing methods in four different ADH1s to be H44R, W54R, W82 (to an unidentified basic amino acid), and P316R [4,7]. We previously produced the H44R enzyme by site-directed mutagenesis and concluded that 5-fold decreases in turnover numbers and catalytic efficiencies could explain the growth of fitter yeast [8]. We have now extended the study by determining how the H15R, W54R, and W82R substitutions affect the steady-state kinetic constants. Furthermore, we correlated the characteristics of six enzymes (kinetic constants, expression levels) with fitness for growth on selective media.

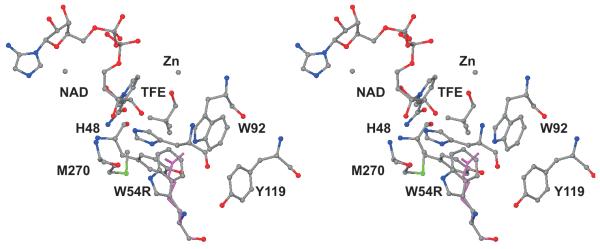

Fig. 1 shows the locations of the substituted amino acid residues. (The residue numbers correspond to the amino acid sequence of the expressed yeast ADH1.) The H15R substitution was chosen to test for a general electrostatic effect on catalysis, as His-15 is on the surface of the protein and not in the active site. The H44R substitution affects coenzyme binding as this residue interacts with the pyrophosphate of the coenzyme [8]. Trp-54 contributes to the hydrophobic substrate binding site and might be expected to affect binding. Trp-82 is distant from the active site but may perturb the protein structure or dynamics. We also included the E67Q enzyme as a test of the general effects of mutations that decrease catalytic activity [9].

Fig. 1.

Stereo view of one subunit of the tetrameric yeast alcohol dehydrogenase showing the locations of the amino acid residues that were substituted. NAD, TFE (trifluoroethanol) and the catalytic zinc atom are shown. The four substituted arginine residues are in magenta near the residue number. Residue 67 is a glutamic acid, which is behind the catalytic zinc and was substituted with a glutamine in a previous study [9]. The structure of the yeast ADH was determined at 2.4 Å (PDB ID: 2HCY).

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Materials

LiNAD+ and Na2NADH were purchased from Roche. DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow was obtained from GE Healthcare and Octyl-Sepharose CL-6B was from Pharmacia P-L Biochemicals. Other chemicals were reagent grade. Oligonucleotide mutamers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology, Coralville, IA.

2.2. Mutagenesis

Substitutions in the wild-type yeast ADH1 gene (obtained from Dr. E. T. Young [10]) were created by using the polymerase chain reaction of the QuickChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene. The SphI genomic fragment (1648 bp) including the ADH1 gene was inserted into the YEp13 plasmid to create the 12.4 kbp YEp13/ADCS vector [9]. A similar plasmid was produced by inserting the Sal1-BamH1 fragment from the YEp13/ADCS vector into the YEPB phagemid [11] to create the 9.7 kbp YEPB/ADC vector. These multicopy shuttle vectors include an ampicillin resistance gene for selection in E. coli, parts of the 2μ yeast plasmid for autonomous replication in yeast, and the LEU2 gene for selection in yeast. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain (302-21#2: adc1 adr2 adm leu2 trp1, from Dr. E. T. Young) produces no active ADH and was used to express the wild-type and mutated ADHs. The substitutions with arginine residues for His-15 and Trp-82 were coded for separately in YEPB/ADC and for His-44 and Trp-54 in YEp13/ADCS with the following oligonucleotides (“forward” sequences given, and complementary “reverse” implied) with sites of mutations underlined: 5′-GTT ATC TTC TAC GAA TCC CGC GGT AAG TTG GAA TAC AAA-3′ (H15R), 5′-C GTT AAA TAC TCT GGT GTC TGT AGA ACT GAC TTG CAC GCT TGG GC-3′ (H44R), 5′-GCT TGG CAC GGT GAC AGA CCA TTG CCA GTT AAG CTA CC-3′ (W54R), 5′-GGT GAA AAC GTT AAG GGC AGA AAG ATC GGT GAC TAC GCC G-3′ (W82R). Plasmid DNA was amplified in E. coli and purified using a Qiagen Maxiprep kit. The mutations were confirmed by sequencing of the complete ADH gene by The University of Iowa DNA Facility. The host yeast were transformed with the Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II kit from Zymo Research. The E67Q mutation in YEp13 was prepared previously [9].

2.3. Yeast growth media

Selective media (2% agar plates) were used to characterize the host and transformed yeast strains. Minimal media (SD) contained 0.67% Bacto Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB), without amino acids, and 2% dextrose, upon which none of the yeast strains should grow. Synthetic complete (SC-Leu) media contained 0.67% YNB, supplemented with the usual 13 amino acids (including tryptophan and threonine added after autoclaving, but not leucine) and adenine, uracil and 2% dextrose, upon which host yeast transformed with the either of the two plasmids should grow. YPD contained 1% Bacto Yeast Extract, 2% Bacto Peptone and 2% dextrose, on which all yeast strains grow. YPD plus 1 μg/mL antimycin A only supports growth of yeast with active ADH1, which is required to ferment the glucose. YPD plus 1 or 10 mM allyl alcohol (added after autoclaving) support growth of yeast that lack active alcohol dehydrogenases, although we found that 10 mM allyl alcohol was required to prevent the growth of the host strain that was transformed with the plasmids expressing wild-type ADH1. Unsealed petri dishes were incubated at 30 °C.

2.4. Enzyme purification and kinetics

Starter cultures of yeast were grown in 50 mL of SC-Leu, and a 1% inoculum was added to 1.5 L YPD in Fernbach flasks at 30 °C. The wild-type and substituted enzymes were purified by procedures described previously [8]. Most of the enzymes were purified in good yield and to homogeneity, but the W54R enzyme bound less well to the DEAE column and seemed to be unstable and heterogeneous after purification. The concentration of enzyme (as active site molarity) was determined by titration with NAD+ in the presence of pyrazole so that correct turnover numbers could be calculated [12].

Initial velocity and product and dead-end inhibition experiments used 83 mM potassium phosphate, 40 mM KCl, and 0.25 mM EDTA, at pH 7.3 and 30 °C (to mimic physiological conditions [13,14]) as done previously [15,16]. Re-distilled 95% ethanol and freshly distilled acetaldehyde were used. Enzymes were diluted with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin in pH 8 buffer and kept on ice during kinetics experiments. Maximum velocities and Michaelis and inhibition constants were determined by varying the concentrations of both substrates (5 x 5 matrix) and fitting the data to the equation for a sequential bi reaction, v = VAB/(KiaKb + KaB + KbA + AB) [17]. Inhibition constants for coenzymes were also determined by competitive inhibition against varied concentrations of the other coenzyme. Concentrations of substrates were adjusted appropriately for the kinetic characteristics of each mutated enzyme. The inhibition constant for 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol was determined by competitive inhibition against varied concentrations of ethanol at a fixed concentration of NAD+. Kinetic data were fitted to appropriate equations using the SEQUEN, COMP, NONCOMP, UNCOMP programs [17].

3. Results

3.1. Enzyme characterization

The mutations were confirmed by sequencing of the complete ADH1 gene in the plasmids. The transformed yeast had the phenotype expected for “fitter” mutants, as these yeast grew on YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol and on YPD + antimycin. As confirmation of the substitutions, the mutated enzymes were purified and subjected to electrophoresis under non-denaturing conditions. The four enzymes with the introduced arginine residues migrated more slowly than the wild-type enzyme at pH 9.5, as expected (Fig. 2). The H44R and W82R enzymes have mobilities intermediate between wild-type and H15R and W54R enzymes, and we presume that masking of the additional positive charge, or anion binding, alters the isoelectric point somewhat. Similar changes in mobility were observed for the D49N and E67Q enzymes [9]. For reference, commercial yeast ADH, which has two additional negatively-charged residues, migrates more rapidly [18].

Fig. 2.

Native, non-denaturing, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of purified, mutated ADHs. The full gel is shown with the origin at the top. The dashed line indicates the position of wild-type enzyme, and numbers at the dye front indicate the expected change in charge due to the substitutions. The gel was 6% acrylamide (12 cm high, 14 cm wide, 1 mm thick) and used the high pH discontinuous buffer system, which separates at pH 9.5 [39]. The high pH is required to separate the wild-type enzyme (with histidine residues) from the forms that retain an additional positive charge above pH 9 (as indicated on the figure). Commercial yeast ADH, which comes from Saccharomyces carlsbergensis, has 2 additional negative charges [18]. The E67Q enzyme also migrates with more positive charge [9]. About 1 unit of enzyme activity in a loading buffer with 10% sucrose, 0.05% Bromophenol Blue, and 0.2 mg/ml of -lactalbumin (to stabilize enzyme activity) was loaded into each lane. The gel was run for one hour at 25 mA, and then for 3 h at 200 V at 4 oC to avoid overheating. The samples were stained for activity (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.25 M ethanol, 1 mM NAD+, 0.024 mg/ml phenazine methosulfate, 0.4 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium) at room temperature and destained in water. (The mutated enzymes can also be separated on a thin 1% agarose gel in 50 mM sodium glycine buffer, pH 9.0, run at 100 V and 2 mA for 1.5 h at 5 °C.)

The steady-state kinetic constants of the mutated enzymes were determined by initial velocity experiments (Table 1). The double reciprocal patterns with varied concentrations of NAD+ and ethanol were typically intersecting and were fitted to the general sequential bi equation. The data with NADH and acetaldehyde often did not give good estimates of Kiq, the inhibition (dissociation) constant for NADH, because Kiq was smaller than Kq (Table 1), and the patterns tended toward being parallel. Thus, product inhibition was used to obtain the inhibition constants for both coenzymes. The errors from the computer fitting were generally less than 20% of the values, but the accuracy of the values (reproducibility among different experiments) is typically within a factor of 2. The good agreement between the equilibrium constant calculated from the Haldane relationship (Keq) and the experimentally determined value of 12 pM [19] indicates good internal consistency among the kinetic constants. The kinetic results are consistent with the ordered bi bi mechanism, which was shown previously for the wild-type and H44R enzymes [8,15,16].

Table 1.

Kinetic constants for wild-type and substituted alcohol dehydrogenases.a

| Kinetic constant | WTb | H15R | H44Rb | W82R | E67Qc | W54R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ka (μM) | 160 | 130 | 150 | 160 | 410 | 18000* |

| Kb (mM) | 21 | 13 | 66 | 22 | 41 | 1300* |

| Kp (mM) | 0.74 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 56 | 91* |

| Kq (μM) | 94 | 190 | 10 | 87 | 160 | 2000* |

| Kia (μM) | 950 | 440 | 260 | 610 | 3500 | 7300 |

| Kiq (μM) | 31 | 12 | 16 | 24 | 29 | 570 |

| V1/Et (s−1) | 360 | 390 | 60 | 56 | 9.9 | 48 |

| V2/Et (s−1) | 1800 | 4000 | 460 | 350 | 730 | 960 |

| V1/EtKb (mM−1s−1) | 17 | 30 | 0.91 | 2.6 | 0.24 | 0.037 |

| V2/EtKp (mM−1s−1) | 2400 | 2300 | 98 | 290 | 13 | 11 |

| Keq (pM)d | 12 | 16 | 29 | 11 | 7.5 | 14 |

| Ki CF3CH2OH (mM) | 2.5 | 19 | 0.98 | 25 | 74 | |

| activity, s−1e | 400 | 480 | 60 | 54 | (15) | 1.7 |

Ka, Kb, Kp, and Kq are the Michaelis constants for NAD+, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and NADH, respectively. Ki values are inhibition constants. V1/Et is the turnover number for ethanol oxidation and V2/Et is the turnover number for acetaldehyde reduction. Kinetics were determined in 83 mM potassium phosphate buffer with 40 mM KCl and 0.25 mM EDTA, pH 7.3, 30 °C. Standard errors of the fits to the appropriate computer programs were typically less than 10 - 20 % of the values, indicating good precision [17], except those marked with * where the errors ranged up to 50 % of the values.

Values from [8].

Values from [9].

Equilibrium constant calculated from the Haldane equation: Keq= (V1KpKiq[H+])/(V2KbKia), where [H+] = 5 × 10−8 M.

Turnover number in standard assay [38] at 30 °C, based on titration of active sites, or protein concentration for the value in parentheses.

The H15R enzyme and wild-type enzymes have similar kinetic constants, consistent with the location of residue 15 on the surface of the protein and not at the active site. ADHs from various species have lysine, glycine or asparagine residues at this site, indicating that the enzyme can tolerate varied amino acids [20]. The similarity of kinetic constants suggests that electrostatic effects are small, at pH 7.3.

As shown previously, the H44R enzyme has modestly increased affinity for coenzymes but somewhat higher Michaelis constants for ethanol and acetaldehyde and decreased turnover numbers [8]. Since the Michaelis constants are not equivalent to the binding constants, the decrease in affinity for alcohol is best determined by comparison to the inhibition constant for trifluoroethanol (an inactive substrate analogue), which is increased 7-fold with the H44R enzyme. The results for the H44R enzyme can be explained by local changes in the active site, since residue 44 interacts with the pyrophosphate of the coenzyme as shown by X-ray crystallography (PDB ID: 2HCY). The horse liver enzyme has an arginine residue (number 47) at this position [21], which shows how an arginine could interact with the pyrophosphate in a model of the yeast enzyme. The arginine/histidine substitutions in human ADH1B and monkey ADH1A also have significant effects on the kinetics [22,23].

The W82R enzyme has Michaelis and dissociation constants (K’s) that are very similar to those for wild-type enzyme, but the turnover numbers for the forward and reverse reactions (V/Et’s) are decreased 5-6-fold. Inhibition constants for NAD+ or NADH, against varied concentrations of the other coenzyme, were not affected when the concentrations of the fixed substrate (acetaldehyde or ethanol) were at the level of their Km values or 4-13 times higher, consistent with an ordered mechanism rather than a rapid equilibrium random mechanism. Ethanol was a non-competitive inhibitor against varied concentrations of acetaldehyde (with a Ki value of 110 ± 18 mM, similar to the value for wild-type enzyme), which is consistent with an ordered mechanism for the reverse reaction in which NADH binds before acetaldehyde [8,15,16]. Trifluoroethanol was a competitive inhibitor against varied concentrations of ethanol and uncompetitive against varied concentrations of NAD+, indicating that NAD+ binds first to free enzyme, followed by ethanol. The Ki value for trifluoroethanol is similar to that found for wild-type enzyme, suggesting that the binding of alcohol is not much affected by the substitution [8,15]. Since residue 82 is quite distant from the active site (Fig. 1), and the site is relatively hydrophobic (Fig. 3), the W82R substitution may alter the local structure and affect overall folding or stability. ADHs from other species have leucine, valine, or phenylalanine residues, suggesting that hydrophobic amino acid residues are favored in this site [20]. The local structural change may also decrease catalytic turnover by affecting protein dynamics that are coupled to the reaction coordinate.

Fig. 3.

Model for the substitution in the W82R enzyme. The arginine residue can overlay most atoms of the tryptophan residue and might be stabilized by electrostatic interactions with Asp-86. However, the hydrophobic interactions with His-138 and Leu-33 within the site may be diminished.

The kinetic constants for the E67Q are significantly different from wild-type enzyme, especially the Michaelis constant for acetaldehyde, the turnover number for ethanol oxidation and the inhibition constant for trifluoroethanol [9]. The mechanism appears to be random for reaction of NAD+ and ethanol, but ordered with NADH binding first for reaction of NADH and acetaldehyde. The glutamic acid residue is located “behind” the catalytic zinc and may be important for local conformational changes that facilitate the replacement of water from the zinc when ethanol and acetaldehyde bind [9,24].

The W54R substitution has large effects on all of the kinetic constants. The concentrations of substrates used for the experiments could not be increased enough to obtain the most precise estimates of the constants, even with shorter path-length cuvettes used for experiments with NADH, but the values obtained are consistent with the Keq obtained from the Haldane relationship and are reasonably good. Some substitutions at the coenzyme binding site (S176F, G202I, S246I, A178:A179L, G204A) also greatly affect coenzyme binding [11]. Since residue 54 is located in the substrate binding site, significant effects on kinetics can be expected. Modeling of the W54R substitution can place the arginine in the active site (Fig. 4), but burying the guanidino group in the hydrophobic pocket would be energetically unfavorable, and we could expect that some rearrangements in the active site could also affect binding of coenzyme. The W54R enzyme is also unstable, perhaps due to loss of catalytic zinc. Kinetic data had to be corrected for loss of activity of diluted enzyme during a kinetics experiment. ADHs from other yeasts have tryptophan at residue 54, but ADHs from other species have a variety of amino acids in this region, apparently affecting substrate specificity. Because of gaps in the sequence alignments with other ADHs, it is difficult to identify the residues corresponding to Trp-54 in yeast ADH1, but candidates include aspartic acid in ADH3 (which acts on hydroxymethyl glutathione), glycine in plant enzymes, and leucine, methionine, and phenylalanine in other enzymes [20]. How such substitutions would affect yeast ADH activity remains an open question. Substitutions of several residues in the binding site have large effects on substrate specificity [25].

Fig. 4.

Model for the substitution in the W54R enzyme. A sterically acceptable substitution of Trp-54 could overlay most atoms and place the guanidino group of Arg-54 into the substrate binding site near the trifluoromethyl group of TFE. However, burying the positively-charged group may be energetically unacceptable, and the structure may undergo considerable changes.

3.2. Growth of fitter yeast

Yeast transformed with the YEp13 or YEPD plasmids were selected for growth on SC-Leu media, since the host yeast lack the LEU2 gene that is contained in the plasmid. Any of the transformed yeast should grow on YPD, but not on minimal media (yeast nitrogen base without amino acids), which was the case. The host yeast (expressing no active ADH) grows on YPD or YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol, but does not grow on YPD + antimycin. The critical test for fitter yeast strains was growth on YPD + antimycin, which requires active ADH1 to support fermentation, and growth on YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol, upon which yeast with wild-type ADH1 will not grow. According to these criteria, yeast transformed with plasmids encoding the H44R, W54R, E67Q, and W82R enzymes were “fitter”, but the H15R transformant was not (Table 2). (ADH1-deficient strains were previously selected with 1 mM allyl alcohol [26], but replica plating from cultures originally streaked onto SC-Leu plates showed growth of all transformants on YPD + 1 mM allyl alcohol, and more stringent conditions with 10 mM allyl alcohol were used for our studies.)

Table 2.

Relative growth rates of transformed yeast and correlation with catalytic efficiencies of ADHs.

| Parameter for yeast with form of ADH | WT | H15R | H44R | W82R | E67Q | W54R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth: YPD + antimycin | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 2+ | 2+ | + |

| Growth: YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol mg ADH/g cell proteina |

0 42 |

0 40 |

+ 68 |

+ 2.8 |

2+ 63 |

3+ 15 |

| V1/EtKbKia, alcohol oxidation, mM−2s−1 | 18 | 68 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 0.068 | 0.0054 |

| Log V1/KbKia, adjusted for [enzyme]b | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 0.63 | −1.1 |

Cell homogenates were assayed for ADH activity [38] and for protein with the BioRad Protein Assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Catalytic efficiency for alcohol oxidation, V1/EtKbKia, was multiplied by mg ADH/g cell protein and the logarithm calculated. Note that V1/KbKia = KeqV2/KpKiq so that either measure of catalysis correlates with growth.

In the initial replica plating, however, it appeared that growth of the W82R transformants was somewhat slower than growth of the H44R, W54R, and E67Q transformants. These observations led us to examine more closely the correlation between growth and the characteristics of the ADH variants. Relative growth rates of the transformed yeast over 3 days on agar plates were estimated. Yeast were grown in liquid SC-Leu media and then diluted serially over a 100-fold range for spotting on selective plates. Fig. 5 shows that growth of all transformants after 3 days was similar on SC-Leu or YPD + 1 mM allyl alcohol, but the W54R and E67Q transformants had grown slowly on YPD + antimycin and very well on YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol, whereas wild-type and H15R transformants had grown well on YPD + antimycin but not with 10 mM allyl alcohol. After one day, yeast with W82R, E67Q, and W54R ADHs had grown more slowly on SC-Leu and YPD + antimycin than the other yeast, and wild-type and H15R transformants had grown more slowly on YPD + 1 mM allyl alcohol. Examining the plates each day for 3 days led to the judgments of the relative growth rates given in Table 2, which shows an inverse correlation between growth in the presence of antimycin or 10 mM allyl alcohol.

Fig. 5.

Relative growth rates of transformed yeast on selective media. Yeast strains were grown to OD600/cm of 4-5 in SC-Leu media at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm and then diluted to different OD levels before spotting 5 μl of culture on SC-Leu, YPD + 1 μg/ml antimycin A, YPD + 1 mM allyl alcohol, and YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol agar plates. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 3 days with cell growth recorded each day. All cultures grew on YPD, but none grew on minimal media lacking tryptophan.

In order to make a semi-quantitative correlation of growth with the kinetics of the ADHs in the transformants, we determined the amount of ADH present in the cultures grown in liquid SC-Leu, assaying cell homogenates for enzyme activity and soluble protein. The measured activities were converted to mg of ADH by using the turnover number or “activity” in the standard assay given in Table 1. The W54R and W82R enzymes were expressed at lower levels than the other enzymes; perhaps this reflects the inherent stability of these enzymes in the yeast. Then we compared the kinetic characteristics of the mutated ADH’s, adjusted for the amounts of ADH with the growth rates. The best correlation showed that overall catalytic efficiency (V1/KbKia) was directly correlated with growth rate on YPD + antimycin and inversely correlated with growth on YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol (Table 2). Total enzyme activity, V1 or V2, or V/Km,substrate did not correlate as well, even when only the rank order was considered. The logarithm of V1/KbKia is best correlated with relative growth rates, which is exponential, but a statistical analysis is not feasible with the present data. It should be noted that catalytic efficiency in the forward reaction (alcohol oxidation) is directly related to catalytic efficiency in the reverse reaction (acetaldehyde reduction) by the equilibrium constant for the reaction, which enzyme catalysis does not change.

The criteria used to define “fitter” yeast are defined operationally for this study as in Fig. 5. However, other growth conditions gave somewhat different results, which we describe here for complete disclosure and impetus for future studies. Yeast transformed with the plasmids with the H44R and E67Q substitutions did not grow on YPD + 10 mM allyl alcohol by replica plating from YPD plates, in contrast to replica plating from SC-Leu plates. The W54R and W82R transformants did grow with 10 mM allyl alcohol, and all four “fitter” transformants grew on SC-Leu and YPD + antimycin, as was observed with replica plating from SC-Leu plates. Perhaps the growth on YPD sensitized the transformants to poisoning by allyl alcohol. We also tried to determine growth rates in liquid culture, using 50 mL of SC-Leu + 1 μg/mL antimycin (and 20 μg/ml tetracycline and 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin to prevent growth of bacteria that could infect the culture during numerous samplings) in 125 mL flasks. The doubling time, measured by OD600 (with dilution to keep the measured OD below 0.5), was about 3 h for all six transformed yeast. (Under the microscope, the cells were confirmed to be budding yeast.) The growth rates may have been limited by factors other than ADH activity. It was previously noted, with surprise, that respiration-deficient strains lacking ADH were able to grow without marked differences compared to wild-type strains [26]. Hypoxic or anoxic atmospheres protect against toxicity by allyl alcohol [27]. These studies suggest that allyl alcohol toxicity is metabolically complex.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structure-function relationships

The kinetic constants for several ADHs from fitter yeast were previously determined at pH 8.8 and 25 °C [3], in contrast to pH 7.3 and 30 °C that we chose for the present studies to be more physiologically relevant. Thus, the kinetic constants from the two studies can be different, because of differential pH effects [8]. For instance, His-44 binds the pyrophosphate of the coenzyme, and a high pH would eliminate electrostatic effects. Nevertheless, the magnitudes of the corresponding kinetic constants for the wild-type enzyme agreed within about 2-fold, and those for H44R were within about 3-fold [8]. On the other hand, the kinetic constants for the W54R enzyme differed by 5-fold or more (Table 1 cf. [4]), but the kinetic constants for this enzyme were difficult to determine because they were so large. The W54R substitution is in the active site (Fig. 4) and severely disrupts binding of coenzymes and substrates.

Many, but not all, of the mutated ADHs from resistant strains had altered electrophoretic mobilities consistent with additional positive charge, such as the H44R, W54R, W82R and P316R enzymes [4]. Our results with the H15R enzyme (not selected from a genetic screen) show that just increasing the positive charge of the ADH does not necessarily produce a fitter yeast. The kinetic constants for the H15R enzyme differ slightly from those of wild-type enzyme. In particular, the binding of coenzymes (Kia and Kiq) appear to be 2-3-fold tighter, and the turnover number for acetaldehyde reduction is 2-fold faster. General electrostatic effects can affect catalysis [28], and studies suggest that binding of coenzymes can be affected by the overall charge on horse liver ADH [29,30]. For yeast ADH1, His-15 is on the “front side” of the enzyme where substrates approach and might provide some electrostatic attraction. However, the effects on kinetics are small and near the limits of accuracy.

The W82R enzyme is interesting because the substitution is distant from the active site, and the substituted amino acid was not identified in the original studies. We chose the W82R substitution because the mutated enzyme from fitter yeast had additional positive charge at pH 8.6, which would probably be due to an arginine or lysine residue [5]. In our study, the kinetic constants (K’s) were very similar to those for wild-type enzyme, but the turnover numbers were decreased about 5-fold. In the studies of the W82 mutant (“S-AA-1”) enzyme (at pH 8.8), all of the kinetic constants were very similar to those for wild-type enzyme [3], which might suggest that the substitution was arginine. Calculation of turnover numbers depends critically on the determination of the concentration of active sites, either with a pure enzyme or by titration, and we can expect variances in different studies. However, if the kinetic constants (K’s) are similar for wild-type and W82R enzymes, why should yeast expressing the W82R enzyme be fitter? Our explanation is that the turnover numbers and the levels of expression of the enzyme are decreased. These results may be due to overall structural changes that affect dynamics of catalysis and protein stability. Because the binding of coenzymes and trifluoroethanol are not much affected by the W82R substitution whereas the turnover numbers are modestly decreased, global protein dynamics appear to affect catalysis.

In accord with other structure-function studies, the results of the present studies show that amino acid residues throughout the protein can contribute to catalysis. In many cases, changes distal from the active site have modest effects on activity, whereas substitutions in the active site have varied effects. Complete kinetic studies are essential to determine how the activity is changed.

4.2. Biochemical and physiological basis of fitter yeast

A major result of this study is that growth on YPD + antimycin (requiring ADH1 activity) is directly correlated with catalytic efficiency of the ADH (adjusted for expression of enzyme), whereas growth on YPD + allyl alcohol is inversely correlated with catalytic efficiency. Because the kinetic definition of overall catalytic efficiency includes the Km for ethanol or acetaldehyde and the Ki for coenzyme, it is reasonable to find a correlation with growth as this kinetic term accounts for the steady-state concentrations of the substrates. Maximum velocities would be difficult to obtain in vivo if concentrations of coenzymes were limiting the activity, as may be the case for the impaired E67Q and W54R enzymes. Nevertheless, why the resistance to allyl alcohol is inversely correlated with enzyme catalysis is a complex issue.

Allyl alcohol is oxidized by yeast ADH to form acrolein, which is toxic to cells, apparently because of reaction of the double bond with sulfhydryl groups of proteins and glutathione and the resulting oxidative stress, but not because of reactive oxygen species [27]. Many genes are required for resistance to acrolein, among them old yellow enzyme (OYE2), which reduces acrolein to the less toxic propionaldehyde [31]. Allyl acohol is a good substrate for ADH, which oxidizes it more efficiently than ethanol, but ADH is 5 times more active in reducing acetaldehyde than in reducing acrolein [32]. (ADH1 can also provide resistance to formaldehyde for yeast [33].) Since disruption of the ADH genes protects yeast from poisoning by allyl alcohol, the activity of ADH is critical for the toxicity of allyl alcohol. Therefore, decreasing the activity of ADH should protect against toxicity. The different growth rates of the yeast transformed with mutated ADHs in the presence of 10 mM allyl alcohol (Fig. 5 and Table 2) can be explained simply by the different rates of formation of acrolein. This explanation makes the reasonable assumption that these mutated ADHs retain similar relative activities on ethanol and allyl alcohol.

ADH is itself inactivated during the oxidation of allyl alcohol in vitro, and dithiothreitol can protect the enzyme [34], apparently by trapping free acrolein. Yeast ADH has cysteine residues (ligated to the zinc in the active site) that are required for enzymatic activity and react especially readily with alkylating agents to destroy activity [35, 36]. Either or both of the two cysteine residues react differentially with chemical agents [37]. Since yeast growing aerobically on YPD do not require ADH, it does not appear that the ADH is inactivated substantially by acrolein in vivo, because if it were, toxicity would be prevented.

Growth on YPD + antimycin, however, requires ADH1 activity. As shown in Fig. 5 and Table 2, the growth rates of transformed yeast are correlated with the catalytic efficiency of the mutated ADHs that they contain. The simple explanation is that ADH1 is required for fermentation. Although the plasmids derived from YEp13 are multicopy, the levels of ADH activity determined in the transformed strains are about the same as in a wild-type yeast. We did not test for growth under dual selection for growth in the presence of both antimycin and allyl alcohol, but the original fitter yeast were selected with petite strains that lacked mitochondria [1].

Wills proposed that the fitter yeast would be resistant to allyl alcohol because the redox state (NAD+/NADH ratio) decreased [3]. Since the oxidation of allyl alcohol is reversible, it is in a steady-state, quasi-equilibrium coupled to the redox state, and the ratio of acrolein to allyl alcohol would be relatively lower in the fitter yeast if the levels of NADH increased. The explanation was supported by direct measurements of NAD+ and NADH levels, and by perturbing the ratio by adding ethanol or acetaldehyde to growth media [4,6]. For instance, adding 2% ethanol to the media decreased the ratio and also decreased the sensitivity of the yeast to allyl alcohol. The shift in redox balance was originally proposed to be related to changes in kinetic constants that affected “cooperativity” in the enzyme mechanism, but we suggest that “fitness” results from decreased catalytic efficiency of the ADHs. (For the sequential bi reaction, “cooperativity” is an illusion because both the ordered bi and rapid equilibrium random mechanisms are described by the same equation, with KiaKb = KaKib.) Decreased rates of reduction of acetaldehyde during fermentation would decrease the rate of growth on YPD + antimycin, and decreased rates of oxidation of allyl alcohol would protect yeast during growth on YPD + allyl alcohol. Substitutions that produce bradykinetic ADHs can explain the physiology of resistance to allyl alcohol and the bradytrophic growth during fermentation.

Highlights.

Fitness correlates with decreased catalytic efficiency of alcohol dehydrogenase.

Fermentation positively correlates with catalysis by alcohol dehydrogenase.

The W54R substitution in the active site has large effects on catalysis and improves fitness.

The W82R substitution, distal to the active site, decreases catalytic turnover and improves fitness.

The H15R substitution has small effects on catalysis, but none on fitness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, Grant GM078446. These experiments were originally designed for an undergraduate biochemistry laboratory course. We thank The University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine DNA Facility for assistance.

Abbreviations

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- amino acid substitutions

e.g.,W54R, indicates that Trp-54 in wild-type enzyme is replaced with Arg-54

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Wills C, Phelps J. A technique for the isolation of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase mutants with altered substrate specificity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1975;167:627–637. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(75)90506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wills C. Controlling protein evolution. Fed. Proc. 1976;35:2098–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wills C. Production of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase isoenzymes by selection. Nature. 1976;261:26–29. doi: 10.1038/261026a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wills C, Kratofil P, Martin T. Functional mutants of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. In: Hollaender A, editor. Genetic Engineering of Microorganisms for Chemicals. Plenum; New York: 1981. pp. 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wills C, Phelps J. Functional mutants of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase affecting kinetics, cellular redox balance, and electrophoretic mobility. Biochem. Genet. 1978;16:415–432. doi: 10.1007/BF00484208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wills C, Martin T. Alteration in the redox balance of yeast leads to allyl alcohol resistance. FEBS Lett. 1980;119:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)81008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wills C, Jörnvall H. Amino acid substitutions in two functional mutants of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Nature. 1979;279:734–736. doi: 10.1038/279734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gould RM, Plapp BV. Substitution of arginine for histidine-47 in the coenzyme binding site of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase I. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5463–5468. doi: 10.1021/bi00475a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ganzhorn AJ, Plapp BV. Carboxyl groups near the active site zinc contribute to catalysis in yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:5446–5454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Williamson VM, Bennetzen J, Young ET, Nasmyth K, Hall BD. Isolation of the structural gene for alcohol dehydrogenase by genetic complementation in yeast. Nature. 1980;283:214–216. doi: 10.1038/283214a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fan F, Plapp BV. Probing the affinity and specificity of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase I for coenzymes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;367:240–249. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Theorell H, Yonetani T. Liver alcohol dehydrogenase-DPN-pyrazole complex: A model of a ternary intermediate in the enzyme reaction. Biochem. Z. 1963;338:537–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cornell NW. Properties of alcohol dehydrogenase and ethanol oxidation in vivo and in hepatocytes. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1983;18(Suppl 1):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].den Hollander JA, Ugurbil K, Brown TR, Shulman RG. Phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the effect of oxygen upon glycolysis in yeast. Biochemistry. 1981;20:5871–5880. doi: 10.1021/bi00523a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ganzhorn AJ, Green DW, Hershey AD, Gould RM, Plapp BV. Kinetic characterization of yeast alcohol dehydrogenases. Amino acid residue 294 and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:3754–3761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Plapp BV, Ganzhorn AJ, Gould RM, Green DW, Jacobi T, Warth E, Kratzer DA. Catalysis by yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1991;284:241–251. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5901-2_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cleland WW. Statistical analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:103–138. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pal S, Park D-H, Plapp BV. Activity of yeast alcohol dehydrogenases on benzyl alcohols and benzaldehydes: Characterization of ADH1 from Saccharomyces carlsbergensis and transition state analysis. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2009;178:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sund H, Theorell H. Alcohol dehydrogenases. The Enzymes. 1963;7:25–83. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sun HW, Plapp BV. Progressive sequence alignment and molecular evolution of the Zn-containing alcohol dehydrogenase family. J. Mol. Evol. 1992;34:522–535. doi: 10.1007/BF00160465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ramaswamy S, Eklund H, Plapp BV. Structures of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase complexed with NAD+ and substituted benzyl alcohols. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5230–5237. doi: 10.1021/bi00183a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hurley TD, Edenberg HJ, Bosron WF. Expression and kinetic characterization of variants of human 1 1 alcohol dehydrogenase containing substitutions at amino acid 47. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:16366–16372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Light DR, Dennis MS, Forsythe IJ, Liu CC, Green DW, Kratzer DA, Plapp BV. α-Isoenzyme of alcohol dehydrogenase from monkey liver. Cloning, expression, mechanism, coenzyme, and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:12592–12599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Plapp BV. Conformational changes and catalysis by alcohol dehydrogenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010;493:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Green DW, Sun HW, Plapp BV. Inversion of the substrate specificity of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:7792–7798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ciriacy M. Genetics of alcohol dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: I. Isolation and genetic analysis of adh mutants. Mutat. Res. 1975;29:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kwolek-Mirek M, Bednarska S, Bartosz G, Bili ski T. Acrolein toxicity involves oxidative stress caused by glutathione depletion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2009;25:363–378. doi: 10.1007/s10565-008-9090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Russell AJ, Fersht AR. Rational modification of enzyme catalysis by engineering surface charge. Nature. 1987;328:496–500. doi: 10.1038/328496a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pettersson G, Eklund H. Electrostatic effects of bound NADH and NAD+ on ionizing groups in liver alcohol dehydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;165:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].LeBrun LA, Plapp BV. Control of coenzyme binding to horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12387–12393. doi: 10.1021/bi991306p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Trotter EW, Collinson EJ, Dawes IW, Grant CM. Old yellow enzymes protect against acrolein toxicity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:4885–4892. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00526-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pietruszko R, Crawford K, Lester D. Comparison of substrate specificity of alcohol dehydrogenases from human liver, horse liver, and yeast towards saturated and 2-enoic alcohols and aldehydes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1973;159:50–60. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Grey M, Schmidt M, Brendel M. Overexpression of ADH1 confers hyper-resistance to formaldehyde in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 1996;29:437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rando RR. Allyl alcohol-induced irreversible inhibition of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974;23:2328–2331. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Plapp BV, Woenckhaus C, Pfleiderer G. Evaluation of N1-(ω-bromoacetamidoalkyl)nicotinamides as inhibitors of dehydrogenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968;128:360–368. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Heitz JR, Anderson CD, Anderson BM. Inactivation of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase by N-alkylmaleimides. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 1968;127:627–636. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Twu JS, Chin CC, Wold F. Studies on the active-site sulfhydryl groups of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1973;12:2856–2862. doi: 10.1021/bi00739a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Plapp BV. Enhancement of the activity of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase by modification of amino groups at the active sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:1727–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Blackshear PJ. Systems for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1984;104:237–255. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)04093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]