Abstract

We report a case of CMV corneal endotheliitis that was treated with intravitreal ganciclovir injection. A 56-year-old man who has suffered from uveitis was referred to our clinic due to corneal endothelial abnormality. Slit lamp examination showed a localized sectoral corneal edema and linear keratic precipitates along the boundary of edema. In spite of treatment with oral steroid and acyclovir, the disease progressed and two new coin-like lesions were developed. After topical ganciclovir and intavitreal injection of ganciclovir, the corneal lesions disappeared.

Keywords: CMV endotheliitis, Intravitreal ganciclovir injection

Linear endotheliitis is an endothelial disease which is characterized by sectorial corneal edema and keratic precipitates (KPs) lines along the boundary of the edema [1]. It has been described as being more difficult to treat than disciform endotheliitis, which is associated with the immune system response to infection [2]. Linear endotheliitis may be caused by viral infection, including infection by the herpes virus [3]. Recently, cytomegalovirus has been reported as another causative agent of linear endotheliitis [1,4-6]. Topical and systemic ganciclovir is commonly used to treat CMV endotheliitis [3-5]. However, systemic ganciclovir has various side effects including pancytopenia or myelosuppression [7].

In this report, we present a case of linear corneal endotheliitis caused by CMV (confirmed by polymerase chain reaction [PCR]). The patient was later treated with topical ganciclovir and intravitreal ganciclovir injection.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man who had recurrent anterior uveitis for the last 30 years was referred to our clinic due to a corneal endothelial abnormality. He had no history of immunologic and infectious disease that may cause an anterior chamber reaction or endothelial abnormality. At his first visit, slit lamp examination showed sectorial corneal edema and KPs along the boundary of the edema (Fig. 1) and mild anterior chamber reaction. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 29 mmHg measured by non-contact tonometry. We prescribed oral acyclovir 400 mg twice a day, topical acyclovir 3% (Herpecid; Samil, Seoul, Korea) 5 times a day, topical prednisolone 1% (Pred forte; Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) every 2 hours, and dorzolamide plus timolol maleate 6.83 mg/mL (Cosopt; Merk & Co, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) twice a day. At his second visit, the corneal lesions were stationary while the anterior chamber reaction was reduced. We prescribed topical 5% NaCl (Muro 128; Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY, USA) every 6 hours for corneal edema and oral prednisolone 20 mg per day. New coin-like corneal lesions developed a week after adding the oral steroid (Fig. 2). CMV endotheliitis was suspected because the new lesions had a coin-like appearance, which is specific for CMV endotheliitis (Fig. 3). Oral steroids were tapered off. The patient rejected treatment with systemic gancyclovir because of his private situation and possible complications. He agreed to topical and intravitreal ganciclovir instead of systemic gancyclovir. Topical acyclovir was changed to topical gancyclovir ophthalmic gel (0.15%; Virgan, Farmila-Thea Farmaceutici SpA, Milan, Italy) and gancyclovir (2 mg/0.05 mL) intra-vitreous injection. During the injection, we removed 0.1 mL of aqueous humor from anterior chamber to prevent IOP elevation. We performed qualitative PCR analysis for CMV only. We did not perform PCR analysis for other pathogens because CMV infection was strongly suspected. DNA extraction was performed using a QIAamp DNA blood mini QIAcube kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. CMV DNA was amplified using a nested PCR technique using two primer sets derived from the CMV glycoprotein B gene region (1st PCR, 5-GGCCGATCCTCTGAGAG TCTGC & 5-GTGGGTGCTCTTGCCTCCAGAG-3; 2nd PCR, 5-CCTAGTGTGGATGACCTACGGGCCA-3 & 5-CAGACACAGTGTCCTCCCGCTCCTC-3). The nested amplification product was visualized on 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and confirmed the expected 249 base pair products. After this point, the corneal lesion seemed to be have improved minimally. The frequency of applying topical steroids (Pred forte) was reduced from 12 to 6 times a day. Qualitative PCR analysis showed the presence of CMV-DNA in the aqueous humour. Ganciclovir (2 mg/0.05 mL) was injected into the vitreous one more time. Ten days later, the patient's corneal edema had almost subsided and the linear KPs had disappeared (Fig. 3). After symptoms and signs associated with endotheliitis abated, the lesions did not recur for more than 6 months, and we did not perform follow-up PCR analysis. Specular microscopy showed a reduced number of endothelial cells (Fig. 4). The patient underwent a cataract operation about a month later.

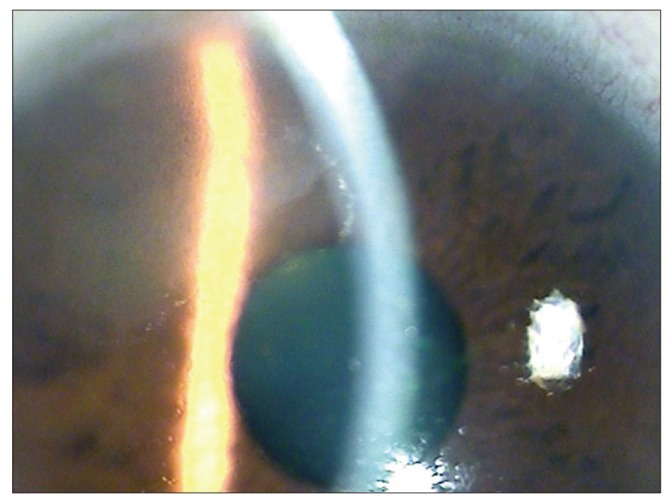

Fig. 1.

Slit lamp examination showed sectorial corneal edema, keratic precipitates along the boundary of edema.

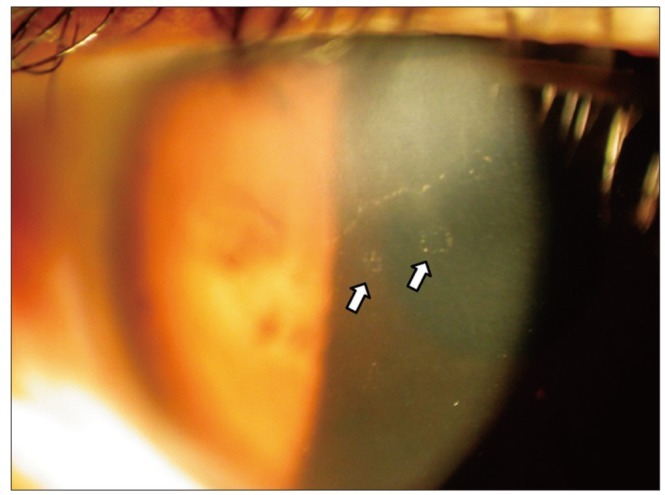

Fig. 2.

Two new coin-like lesions pointed by arrows developed 1 week after adding oral steroids to the treatment course.

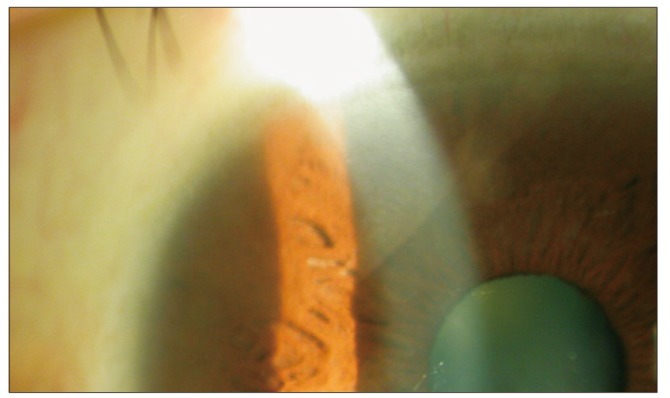

Fig. 3.

After ganciclovir 2 mg/0.05 mL was injected into the intra-vitreous space, corneal edema almost subsided and linear keratic precipitates disappeared. The cornea returned to a normal state.

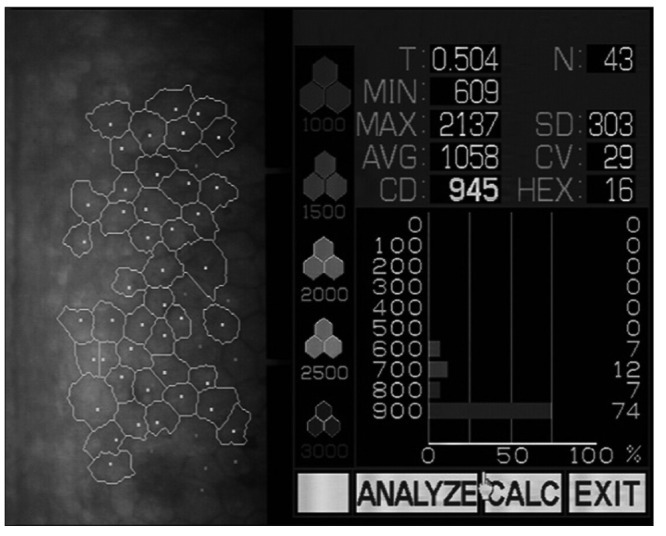

Fig. 4.

Specular microscopy shows the reduced number of endothelial cells after treatment of linear endotheliitis.

Discussion

CMV has been reported as a causative agent of linear endotheliitis [1,4-6]. We confirmed the presence of CMV-DNA in the aqueous humour with qualitative PCR analysis. Topical and systemic ganciclovir is commonly used for treating CMV endotheliitis [1,4-6]. However, systemic ganciclovir has the serious side effects of myelosuppression and carcinogenesis [8,9]. In this case, intravitreal ganciclovir injection was performed twice for CMV endotheliitis, which is effective against CMV endotheliitis and does not have systemic side effects. Intraocular injections of anti-viral agents instead of systemic agents can be an effective treatment that reduces systemic side effects [9-12]. While there has been no report of intracameral ganciclovir injection and corneal endothelial toxicity due to ganciclovir, intravitreal ganciclovir injection has been commonly used for the treatment of CMV retinitis [9,11,12]. Intravitreal injection of ganciclovir may have side effects such as endophthlamitis [13], intraocular hemorrhage [14], crystallization of the vitreous humor [15], and retinal toxicity [16,17]. In our case, the concentration of intravitreal ganciclovir was set to 2 mg/0.05 mL, which has been used in other previous studies [18,19]. As described in a previous publication, intravitreal injection of ganciclovir should be done every ten days in order to maintain an adequate concentration in the aqueous humor [20]. In this case, there were no side effects associated with intravitreal ganciclovir injection. The cataract operation was carried out a month later. This patient's cataracts may be due to long-term use of steroids to treat anterior uveitis. His cataracts had already advanced when he first visited our clinic; he had used topical steroid for the last 30 years. In addition, cataracts have been reported as a complication of intravitreal ganciclovir injection [11].

In this case study, we treated CMV endotheliitis with topical ganciclovir and intravitreal ganciclovir injection, which was effective in treating CMV endotheliitis without systemic side effects. Topical ganciclovir and intravitreal ganciclovir injection can be considered as an effective treatment option for CMV endotheliitis that avoids systemic side effects.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Suzuki T, Ohashi Y. Corneal endotheliitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23:235–240. doi: 10.1080/08820530802111010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ. Cornea. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011. pp. 961–971. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohashi Y, Yamamoto S, Nishida K, et al. Demonstration of herpes simplex virus DNA in idiopathic corneal endotheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:419–423. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koizumi N, Yamasaki K, Kawasaki S, et al. Cytomegalovirus in aqueous humor from an eye with corneal endotheliitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:564–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koizumi N, Suzuki T, Uno T, et al. Cytomegalovirus as an etiologic factor in corneal endotheliitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:292–297.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chee SP, Bacsal K, Jap A, et al. Corneal endotheliitis associated with evidence of cytomegalovirus infection. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:798–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellay J, Venetz JP, Aubert JD, et al. Treatment of cytomegalovirus infection or disease in solid organ transplant recipients with valganciclovir. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:949–951. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall BC, Koch WC. Antivirals for cytomegalovirus infection in neonates and infants: focus on pharmacokinetics, formulations, dosing, and adverse events. Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11:309–321. doi: 10.2165/11316080-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yutthitham K, Ruamviboonsuk P. The high-dose, alternate-week intravitreal ganciclovir injections for cytomegalovirus retinitis in acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88(Suppl 9):S63–S68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JS, Joo MJ, Yoo JH. Histological changes of the retinal following high dose intravitreal ganciclovir injection in rabbit. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;38:1172–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ausayakhun S, Yuvaves P, Ngamtiphakom S, Prasitsilp J. Treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS patients with intravitreal ganciclovir. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88(Suppl 9):S15–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arevalo JF, Garcia RA, Mendoza AJ. High-dose (5000-microg) intravitreal ganciclovir combined with highly active antiretroviral therapy for cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-infected patients in Venezuela. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15:610–618. doi: 10.1177/112067210501500512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinemann MH. Long-term intravitreal ganciclovir therapy for cytomegalovirus retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1767–1772. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020849025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager RD, Aiello LP, Patel SC, Cunningham ET., Jr Risks of intravitreous injection: a comprehensive review. Retina. 2004;24:676–698. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choopong P, Tesavibul N, Rodanant N. Crystallization after intravitreal ganciclovir injection. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:709–711. doi: 10.2147/opth.s10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng KT, Lam WC, Parker JA, Yucel YH. Retinal toxicity of intravitreal ganciclovir in rabbit eyes following vitrectomy and insertion of silicone oil. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saran BR, Maguire AM. Retinal toxicity of high dose intravitreal ganciclovir. Retina. 1994;14:248–252. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199414030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang YS, Shen CR, Chang SH, et al. The validity of clinical feature profiles for cytomegaloviral anterior segment infection. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1510-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang YS, Lin KK, Lee JS, et al. Intravitreal loading injection of ganciclovir with or without adjunctive oral valganciclovir for cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chee SP, Jap A. Cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis: outcome of treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1648–1652. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.167767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]