Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of study was to compare blood glucose in capillary finger-prick blood and gingival crevice blood using a self-monitoring blood glucose device among patients with gingivitis or periodontitis.

Methods

Thirty patients with gingivitis or periodontitis and bleeding on probing (BOP) were chosen. The following clinical periodontal parameters were noted: probing depth, BOP, gingival bleeding index, and periodontal disease index. Blood samples were collected from gingival crevicular blood (GCB) and capillary finger-prick blood (CFB). These samples were analyzed using a glucose self-monitoring device.

Results

Descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out in the present study. Data were analyzed using a Pearson's correlation coefficient and Student's t-test. A r-value of 0.97 shows very strong correlation between CFB and GCB, which was statistically highly significant (P<0.0001).

Conclusions

The authors conclude that GCB may serve as potential source of screening blood glucose during routine periodontal examination in populations with an unknown history of diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Blood glucose self-monitoring, Diabetes mellitus, Gingival hemorrhage, Periodontal diseases

INTRODUCTION

The increasing prevalence of obesity and physical inactivity due to population growth, aging, urbanization has prompted the rise in the incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM). The prevalence of DM for all age groups worldwide was estimated to be 2.8% in 2000 and 4.4% in 2030 [1]. The countries with the largest number of people with DM will be India, China, and the United States by 2030. It is estimated that every fifth person with DM will be an Indian [2]. Because of these sheer numbers, the economic burden due to diabetes in India is among the highest in the world [2]. About half of diabetic patients are undiagnosed [3], as DM is asymptomatic in its early stage and can remain undiagnosed for many years. Screening for type 2 DM would alone lead to earlier recognition of cases, with the potential to intervene earlier in the disease course. Early diagnosis may prevent long term complications [3].

Community screening is not a cost-effective approach to screening for DM [4-6]. It may best be performed in primary care as part of a review of a patient's health. Other settings such as dental clinics may be appropriate. There are large numbers of patients who seek dental treatment each year and there is an association between periodontal disease and DM. The two reinforce each other [7-9]. The dentist may play an important role in the health team by participating in the search for undiagnosed asymptomatic DM.

In this study we used a readily available self-monitoring device (SMD) as a simple method for rapid monitoring of the glucose level in the blood. We compared the blood glucose level between gingival crevicular blood (GCB) and capillary finger prick blood (CFB). The purpose of this study was to assess the usefulness of an SMD for the estimation of the GCB glucose level during routine periodontal examinations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection criteria

The study population was recruited from patients visiting the Department of Periodontology, Tatyasaheb Kore Dental College and Research Centre, New Pargaon. A total of 30 patients (age range, 25 to 70 years) with gingivitis or periodontitis, at least one site with positive bleeding on probing (BOP), were randomly selected for the study. Exclusion criteria included the following: any indication for antibiotic prophylaxis, any bleeding disorder, severe systemic disease such as cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, immunologic, or hematological disorders, and any medication interfering with the coagulation system.

Consent forms were duly signed by the participants. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics and research committee.

Clinical examination

Data was recorded by using the probing depth, BOP, gingival bleeding index (GBI) [10], and periodontal disease index (PDI) [11], all measured by the same examiner.

All of the sites were probed by a Williams probe, inserted into the gingival sulcus, as is commonly done during a periodontal examination. When the probe was removed, the gingival crevice was observed for bleeding [12]. One site with profuse BOP was chosen for testing (GCB). The sites most commonly selected were the interproximal area of the maxillary premolar and molar regions. These areas were isolated with cotton rolls to prevent saliva contamination and dried with compressed air, and the remaining fluid in the site was wiped out using a piece of gauze.

Collection of GCB and CFB

For the collection of the GCB sample, we selected a readily available SMD (OneTouch Horizon Blood Glucose Monitoring System, Johnson and Johnson Medical, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) with a compact design that facilitated intraoral collection requiring only a small quantity of blood for an accurate reading. The SMD was introduced intraorally with the test strip in place and blood was allowed to flow onto its reactive area according to the manufacturer's instructions. The test strip was prevented from contacting the tooth, and its entry into the sulcus was also avoided. Immediately after measuring the GCB, the CFB was assessed using the same glucose SMD. The pad of the finger was wiped with alcohol, allowed to dry, and then punctured with a sterile lancet. A CFB sample was drawn onto the test strip preloaded in the SMD. The GCB and CFB glucose readings were recorded.

These CFB readings were viewed as "casual" readings because they were taken without regard to the time of meals. Study participants with elevated casual readings were referred to primary care providers for a more detailed medical evaluation [13].

RESULTS

A descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out in the present study. Results of continuous measurements are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) (min-max) and results of categorical measurements are presented as number (%). Significance has been assessed at a 5% level of significance. The Pearson's correlation has been used to find the correlation between the variables, and the significance of correlation has been obtained using the Student's t-test.

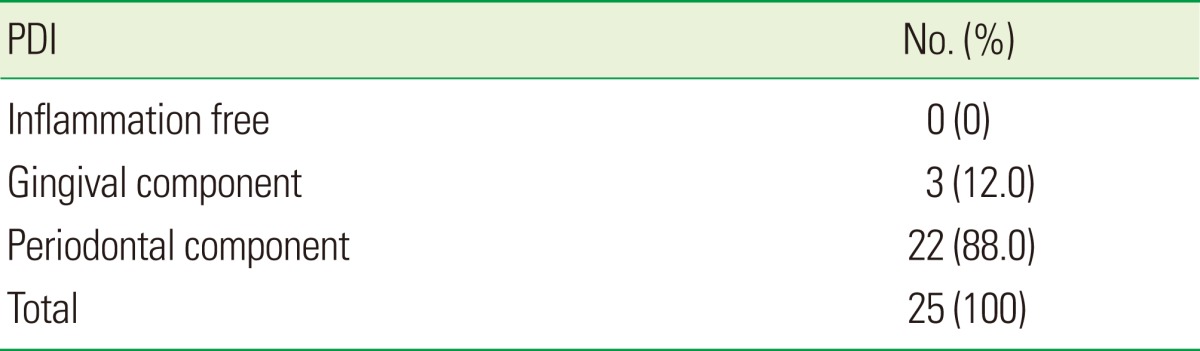

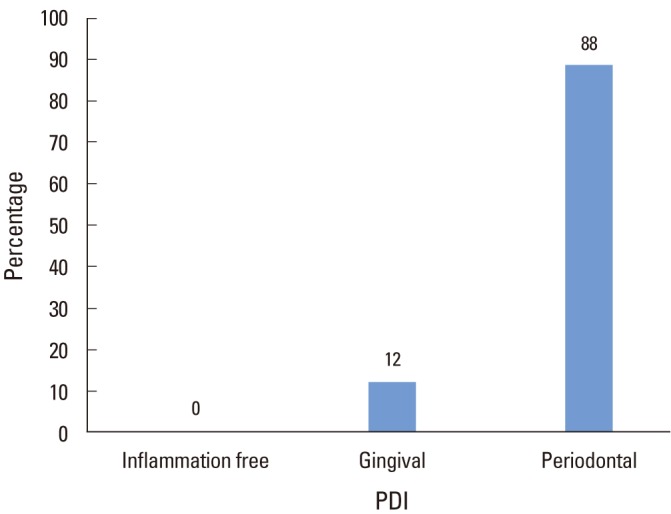

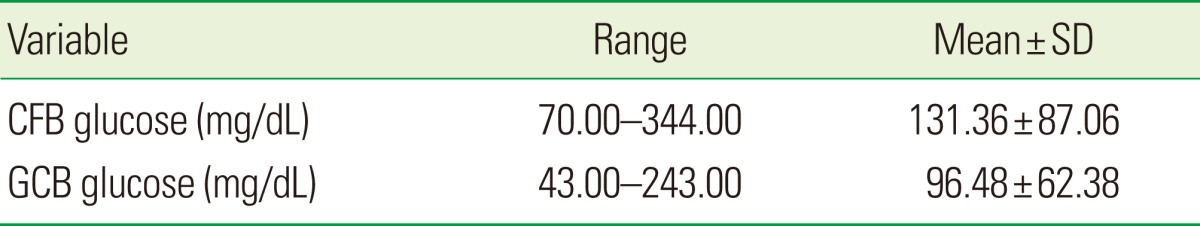

Among the 30 patients, the blood glucose in GCB could be determined in only 25 patients, of which 88% comprised periodontitis cases and 12% gingivitis cases (Table 1, Fig. 1). In the remaining 5 cases, the volume of blood procured on probing was insufficient for collection. Of the 25 successfully tested patients, 3 revealed elevated blood glucose levels. According to epidemiological data on DM in urban India, the ratio of the unknown to known diabetic population is 1.8:1 and the prevalence of undiagnosed DM is estimated to be 7.2%; in the present study, it is 12% [14]. The glucose measurement from the GCB sample ranged from 43 to 243 mg/dL with a mean of 96.48±62.38 mg/dL and the glucose measurement obtained from the CFB ranged from 70 to 344 mg/dL with a mean of 131.9±61.1 mg/dL (Table 2).

Table 1.

Periodontal disease index (PDI).

Figure 1.

Distribution of periodontal disease index (PDI) score for sample.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

SD: standard deviation, CFB: capillary finger-prick blood, GCB: gingival crevicular blood.

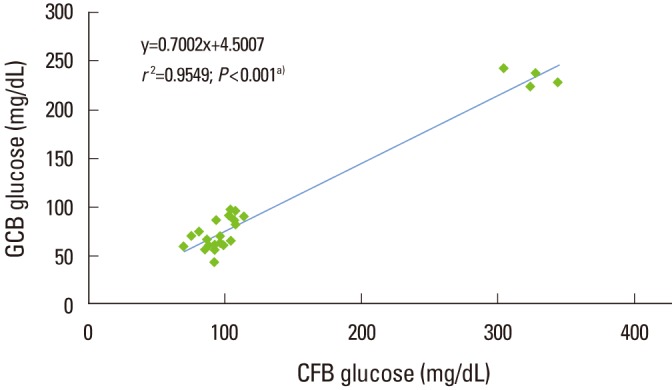

Pearson's correlation coefficient showed a positive correlation between GCB and CFB (Table 3). The linear relationship between GCB and CFB is drawn graphically in a scatter plot (Fig. 2). A r-value of 0.97 shows a very strong correlation between CFB and GCB, which was statistically highly significant (P<0.0001).

Table 3.

Pearson's correlation between CFB and GCB glucose.

CFB: capillary finger-prick blood, GCB: gingival crevicular blood.

a)Indicates high statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Linear regression of gingival crevicular blood (GCB) sample measurements on capillary finger-prick blood (CFB) sample reading. a)High statistical significance (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

DM is a complex metabolic disorder. Periodontitis is considered as the sixth complication of DM [15]. Data has shown that the prevalence of the DM is greater among individuals with periodontitis than healthy individuals. Adequate blood is extravasated from the gingival crevice during routine oral examination in dental clinics. With regard to the significance of early detection of DM and the need for an easy and quick method for screening for DM, we planned to use this extravasated blood from the gingival crevice for estimation of the blood glucose level using SMD.

The results of the present study are in agreement with the study conducted by Shetty et al. [16]. Strauss et al. [17] reported that GCB samples are suitable to screen for DM in individuals with sufficient BOP. However, they failed to give results in individuals with little or no BOP. Sarlati et al. [18] reported that GCB is useful for testing blood glucose during routine periodontal examination in subjects with DM and periodontitis, but not in those without DM. The present study reiterates the results by Parker et al. [19] and Beikler et al. [20]: a strong correlation was observed between blood glucose measured in GCB and CFB when diabetic and nondiabetic patients with moderate to advanced periodontitis were examined. Khader et al. [21] reported that GCB can be an acceptable source for measuring the blood glucose level. In contrast to the above study, Muller and Behbehani [22] failed to obtain any correlation between GCB and CFB.

The results of the present study revealed a higher correlation between GCB and CFB with a smaller sample size. A large study sample should be able to demonstrate robustness in the correlation between GCB and CFB.

From the above discussion, it can be concluded that GCB may serve as a potential source for screening of blood glucose during routine periodontal examination in populations with an unknown history of DM. This study sheds light on the screening of individuals not suspected of DM, using GCB blood samples. Thus, with minimal cost and time investment for patients and clinicians, dental professionals can play a critical role in supporting their patients' overall health. The technique is safe, easy to perform, and comfortable for the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. K.P. Suresh for statistical analysis.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Express Healthcare. Diabetes in India: current status [Internet] Mumbai: Express Healthcare; c2001. [cited 2012 Feb 16]. Available from: http://healthcare.financialexpress.com/200808/diabetes02.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris MI, Eastman RC. Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16:230–236. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dmrr122>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glümer C, Yuyun M, Griffin S, Farewell D, Spiegelhalter D, Kinmonth AL, et al. What determines the cost-effectiveness of diabetes screening? Diabetologia. 2006;49:1536–1544. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward S, Simpson E, Davis S, Hind D, Rees A, Wilkinson A. Taxanes for the adjuvant treatment of early breast cancer: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:1–144. doi: 10.3310/hta11400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wee LE, Koh GC. The effect of neighborhood, socioeconomic status and a community-based program on multi-disease health screening in an Asian population: a controlled intervention study. Prev Med. 2011;53:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:51–61. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mealey BL, Rethman MP. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus. Bidirectional relationship. Dent Today. 2003;22:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurav A, Jadhav V. Periodontitis and risk of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes. 2011;3:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramfjord SP. The Periodontal Disease Index (PDI) J Periodontol. 1967;38:Suppl:602–Suppl:610. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker RC, Rapley JW, Isley W, Spencer P, Killoy WJ. Gingival crevicular blood for assessment of blood glucose in diabetic patients. J Periodontol. 1993;64:666–672. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes: 2007. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 1):S4–S41. doi: 10.2337/dc07-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diabetes India. The Indian task force on diabetes care in India [Internet] Diabetes India; [cited 2012 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.diabetesindia.com/diabetes/itfdci.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shetty S, Kohad R, Yeltiwar R, Shetty K. Gingival blood glucose estimation with reagent test strips: a method to detect diabetes in a periodontal population. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1548–1555. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss SM, Wheeler AJ, Russell SL, Brodsky A, Davidson RM, Gluzman R, et al. The potential use of gingival crevicular blood for measuring glucose to screen for diabetes: an examination based on characteristics of the blood collection site. J Periodontol. 2009;80:907–914. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarlati F, Pakmehr E, Khoshru K, Akhondi N. Gingival crevicular blood for assessment of blood glucose levels. J Periodontol Implant Dent. 2010;2:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker RC, Rapley JW, Isley W, Spencer P, Killoy WJ. Gingival crevicular blood for assessment of blood glucose in diabetic patients. J Periodontol. 1993;64:666–672. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beikler T, Kuczek A, Petersilka G, Flemmig TF. In-dental-office screening for diabetes mellitus using gingival crevicular blood. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:216–218. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khader YS, Al-Zubi BN, Judeh A, Rayyan M. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus using gingival crevicular blood. Int J Dent Hyg. 2006;4:179–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2006.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller HP, Behbehani E. Methods for measuring agreement: glucose levels in gingival crevice blood. Clin Oral Investig. 2005;9:65–69. doi: 10.1007/s00784-004-0290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]