Abstract

Background

The efficacy of AQX-1125, a small-molecule SH2-containing inositol-5′-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) activator and clinical development candidate, is investigated in rodent models of inflammation.

Experimental Approach

AQX-1125 was administered orally in a mouse model of passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) and a number of rodent models of respiratory inflammation including: cigarette smoke, LPS and ovalbumin (OVA)-mediated airway inflammation. SHIP1 dependency of the AQX-1125 mechanism of action was investigated by comparing the efficacy in wild-type and SHIP1-deficient mice subjected to an intrapulmonary LPS challenge.

Results

AQX-1125 exerted anti-inflammatory effects in all of the models studied. AQX-1125 decreased the PCA response at all doses tested. Using bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell counts as an end point, oral or aerosolized AQX-1125 dose dependently decreased the LPS-mediated pulmonary neutrophilic infiltration at 3–30 mg kg−1 and 0.15–15 μg kg−1 respectively. AQX-1125 suppressed the OVA-mediated airway inflammation at 0.1–10 mg kg−1. In the smoke-induced airway inflammation model, AQX-1125 was tested at 30 mg kg−1 and significantly reduced the neutrophil infiltration of the BAL fluid. AQX-1125 (10 mg kg−1) decreased LPS-induced pulmonary neutrophilia in wild-type mice but not in SHIP1-deficient mice.

Conclusions

The SHIP1 activator, AQX-1125, suppresses leukocyte accumulation and inflammatory mediator release in rodent models of pulmonary inflammation and allergy. As shown in the mouse model of LPS-induced lung inflammation, the efficacy of the compound is dependent on the presence of SHIP1. Pharmacological SHIP1 activation may have clinical potential for the treatment of pulmonary inflammatory diseases.

Linked Article

This article is accompanied by Stenton et al., pp. 1506–1518 of this issue. To view this article visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.12039

Keywords: SHIP1, inflammation, pulmonary, chemotaxis, PI3K, COPD, asthma

Introduction

Small-molecule agonists of SH2-containing inositol-5′-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) have been shown to inhibit the PI3K pathway in haematopoietic cells (Ong et al., 2007). Moreover, the pharmacological properties of AQX-1125, a next-generation SHIP1 activator, were described in part 1 of the current series of papers (Stenton et al., 2013).

SHIP1 has been implicated in the regulation of myeloid and lymphoid development, cell activation and cell death/survival. Valuable information regarding the functional roles of SHIP1 has come from the characterization of SHIP1−/− mice (Helgason et al., 1998; Oh et al., 2007). These animals are viable and fertile but have a shortened lifespan. They also have a higher number of granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages and exhibit progressive splenomegaly and massive myeloid infiltration of the lungs (Helgason et al., 1998; Oh et al., 2007; Maxwell et al., 2011). Macrophages, mast cells, T-cells, B-cells, dendritic cells and natural killer cells isolated from SHIP1−/− mice exhibit functional deficiencies of variable degree (Helgason et al., 1998; Oh et al., 2007). By characterizing the phenotype of SHIP1−/− mice, SHIP1 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases including allergic inflammation and asthma (Haddon et al., 2009), acute lung injury (Strassheim et al., 2005) and inflammatory bowel disease (Kerr et al., 2011).

With this body of evidence linking SHIP1 to pulmonary inflammation and allergic disease, and pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution characteristics suitable for in vivo testing, the efficacy of the SHIP1 activator, AQX-1125, was investigated in various allergic and pulmonary inflammatory diseases, including lipopolysaccharide-, ovalbumin- (OVA) and smoke-induced airway inflammation.

Methods

Animals

In vivo animal use protocols were approved by the local ethics committees. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). Animals were acclimated for a minimum of 3 days after arrival in the animal facilities and were allowed free access to food and water with a 12 hour light/dark cycle maintained.

Mouse passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) model

Based on the methods of Teshima et al. (1998), male BALB/c mice (8 weeks old) were injected intradermally in the right ear with 25 ng of anti-DNP-IgE. The left ears were not injected and served as a negative control. Twenty-four hours post-injection, AQX-1125 or vehicle (10 mL kg−1 dose volume) was administered once by oral gavage in saline. Sixty minutes after dosing, animals received a tail vein injection of 2% Evans' blue (0.22 μm filtered, in 200 μL saline) followed by a second tail vein injection of 100 μg dinitrophenyl-human serum albumin (DNP-has; in 200 μL PBS). Sixty minutes following the DNP-HSA injection, mice were killed and ear biopsies were collected, with 4 mm punches placed into 100 μL formamide and incubated overnight at 70°C. Eluents were read using a SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 620 nm. Background readings from all samples were taken at 740 nm.

Pulmonary inflammation model induced by intratracheal (IT) LPS administration in rats

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (230 ± 10 g) received AQX-1125 or vehicle (saline) once daily for 4 consecutive days by oral gavage (10 mL kg−1 dose volume), followed by LPS administration (Beck-Schimmer et al., 1997). The last dose of AQX-1125 or vehicle was administered 2 h before IT challenge with ∼50 μg kg−1 of Escherichia coli LPS (serotype O111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Dexamethasone acted as a reference standard, administered once orally 2 h before LPS challenge. Rats were anaesthetized 4 or 24 h after LPS challenge, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. Total leukocyte cell numbers and cell differential populations in BAL were then determined. Inflammatory mediator content was determined by Rules Based Medicine (Austin, TX, USA) using a Rodent Multi-Analyte Profile Luminex-based analysis (Heuer et al., 2005).

The efficacy of aerosolized AQX-1125 on pulmonary inflammation induced by IT LPS was also determined. AQX-1125 was administered in saline (0.15, 1.5 or 15 μg kg−1; in 50 μL dose volume) qd for 4 days by aerosolization using a PennCentury device. The last dose was administered 2 h before IT challenge with ∼50 μg kg−1 of E. coli lipopolysaccharide as described above. Dexamethasone in saline was administered as a reference standard (single oral dose) 2 h before LPS challenge. Rats were anaesthetized 24 h after LPS challenge, and BAL was performed and cell counts determined as described above.

Pulmonary inflammation induced by IT LPS administration in wild-type or SHIP1 knockout mice

Wild-type (SHIP1+/+), or SHIP1 knockout (SHIP1−/−) male and female BALB/c mice weighing 20–30 g (bred at the BC Cancer Agency, Vancouver, BC, Canada) received AQX-1125 or vehicle (saline) once daily for 4 consecutive days by oral gavage (10 mg kg−1; 7.5 mL kg−1 dose volume), followed by LPS administration (Birrell et al., 2004). The last dose of AQX-1125 or vehicle was administered 2 h before nasal challenge with E. coli LPS (serotype O111:B4, in sterile saline, 10 μg in 50 μL saline per mouse). Mice were killed 18 h after LPS challenge and BAL was performed to determine total leukocyte cell numbers and cell differentials.

OVA-induced asthma model in the rat

Male Brown Norway rats weighing 230 ± 10 g were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of 1 mL sterile phosphate buffered saline containing 1.0 mg OVA and 11.7 mg of Al(OH)3 adjuvant on 3 consecutive days (days 1, 2 and 3). Sham-sensitized rats received 1 mL sterile PBS alone (Stenton et al., 2000). AQX-1125 was administered once a day for 3 days by oral gavage (10 mL kg−1 dose volume) on days 19, 20 and 21. Rats were challenged on day 21, 2 h after AQX-1125 administration, with aerosolized OVA (1% in PBS) for 20 min or with PBS alone. On day 22, rats were killed, followed by BAL analysis. The reference standard dexamethasone was formulated in carboxymethylcellulose and administered twice per day on days 18, 19, 20 and 21 as a positive control. BAL and lung homogenates were used for determining inflammatory mediator content (Rules Based Medicine).

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of the efficacy of AQX-1125 in the OVA-induced lung inflammation model

The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships and duration of action of AQX-1125 was investigated using the model of OVA-induced pulmonary inflammation. AQX-1125 was administered once a day for 3 days by oral gavage in saline (3 or 10 mg kg−1; 10 mL kg−1 dose volume) and animals were challenged with OVA as described above, 2, 4, 8, 24 or 48 h after the last dose of AQX-1125. Parallel groups of rats were treated the same way, however, at the corresponding challenge time, plasma or lung samples were collected for determination of drug content, enabling the correlation between plasma and lung AQX-1125 concentrations at the time of challenge and the anti-inflammatory efficacy of AQX-1125.

Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation model in mice

Male BALB/c mice weighing 25 g were treated with AQX-1125 alone (30 mg kg−1; 10 mL kg−1 dose volume) or in combination with dexamethasone (1 mg kg−1; 10 mL kg−1 dose volume), administered once a day for 15 days by oral gavage in sterile saline. Treatment with dexamethasone alone (1 mg kg−1; 10 mL kg−1 dose volume) was also assessed. Mice were exposed to cigarette smoke for 14 days (three cigarettes at 9:30 a.m., 12:30 p.m. and 3:30 p.m. daily; Vlahos et al., 2006). Cigarettes were commercially available filter-tipped, manufactured by Philip Morris and consisted of 16 mg or less of tar and 1.2 mg or less of nicotine. On day 15, mice were killed, followed by BAL analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by anova followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. Smoke-induced lung inflammation data were analysed using anova followed by Student Newman Keuls.

Results

AQX-1125 exerts anti-inflammatory effects in a mouse PCA model

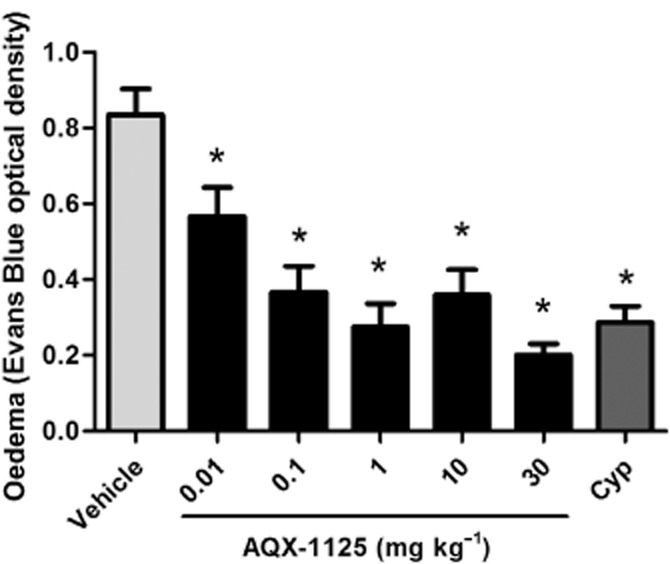

PCA-induced oedema formation was markedly and dose dependently reduced by AQX-1125. At 0.01–30 mg kg−1, the efficacy of the compound was comparable to that of the positive control antihistaminic/antiserotonin/antimuscarinic agent, cyproheptadine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Efficacy of AQX-1125 or cyproheptadine (Cyp, 1 mg kg−1) in a mouse PCA model. Mice were administered AQX-1125 by oral gavage followed by an i.v. administration of Evans Blue 60 min later. The PCA response was induced by i.v. DNP-HSA for 60 min. Evans Blue was extracted from ear punches by dimethyl formamide incubation and the data are presented as the optical density (620 nm). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 10), *P < 0.05 denotes the anti-inflammatory effect of AQX-1125 or of cyproheptadine, compared to the response of the vehicle-treated control animals.

AQX-1125 exerts anti-inflammatory effects in a pulmonary inflammation model induced by IT LPS administration in a SHIP1-dependant manner

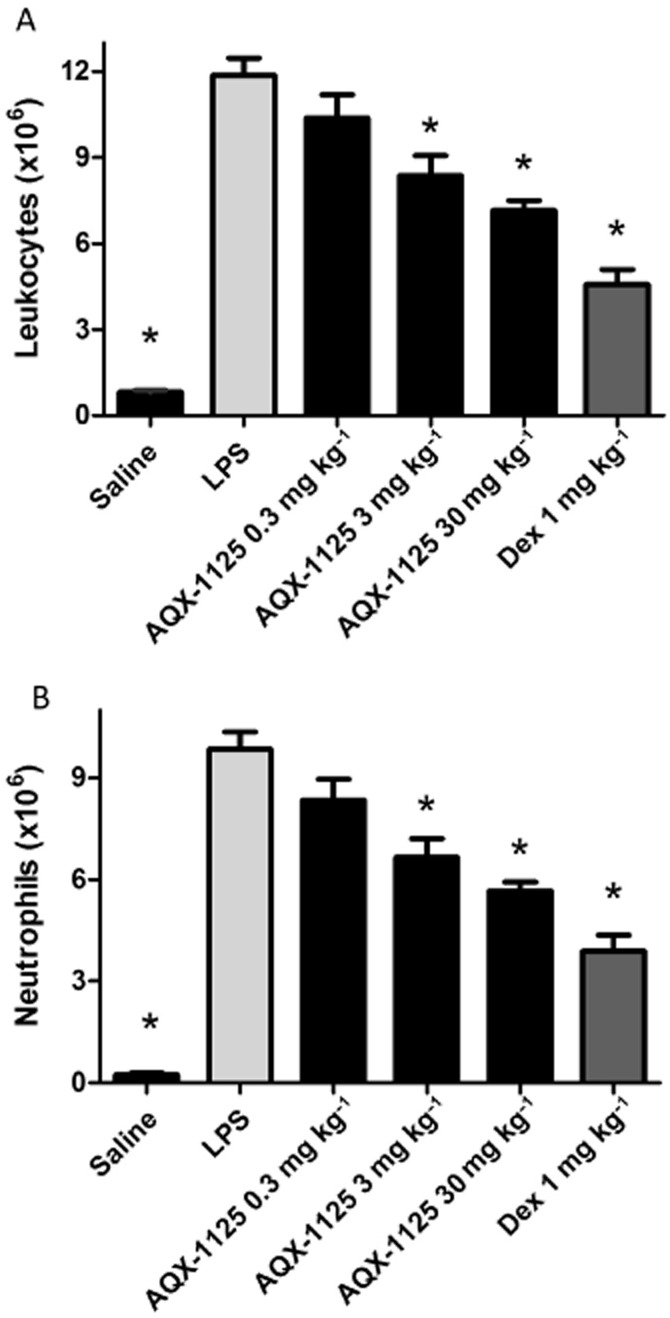

Anti-inflammatory effects of AQX-1125 were observed in a model of LPS-mediated airway inflammation. Total leukocyte and neutrophil data are shown in Figure 2. Neutrophil infiltration was decreased in a dose-dependent manner beginning at 0.3 mg kg−1 with significant (P < 0.05) inhibition of 33 and 43% observed at 3 and 30 mg kg−1 respectively. At a dose of 30 mg kg−1, the effect of AQX-1125 was approaching that of the positive control compound dexamethasone.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of AQX-1125 on total leukocyte counts and neutrophil infiltration of the airways in the rat LPS-induced lung inflammation model. Rats were administered AQX-1125 by oral gavage, once per day for 4 consecutive days, followed by LPS challenge 2 h after the last dose. BAL was performed 24 h after LPS challenge. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the absolute leukocyte counts (A) and the neutrophil counts (B) (×106 cells) (n = 5–9), *P < 0.05 denotes the anti-inflammatory effect of AQX-1125 or dexamethasone, compared to the response of the vehicle-treated control animals.

To further characterize the anti-inflammatory effects of AQX-1125 during LPS-mediated pulmonary inflammation, the production of multiple inflammatory mediators was measured in the BAL fluid. BAL samples were taken from PBS controls, LPS controls, AQX-1125 (10 mg kg−1) and dexamethasone (1 mg kg−1) groups for the analysis of 59 inflammatory markers using multi-analyte Luminex profiling. Table 1 shows the list of mediators that were affected by AQX-1125 and/or dexamethasone. AQX-1125 decreased the LPS-induced production of multiple pro-inflammatory mediators, and exhibited a characteristic response pattern that was different from that of the positive control anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid dexamethasone.

Table 1.

Effect of AQX-1125 and dexamethasone on BAL inflammatory mediator concentrations in the rat model of LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation

| Analytes | PBS | LPS | AQX-1125 (10 mg kg−1) | Dexamethasone (1 mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloperoxidase (ng mL−1) | 2.1 ± 0.4* | 25.8 ± 1.6 | 17.3 ± 3.0* | 6.6 ± 2.2* |

| Leukaemia inhibitory factor (pg mL−1) | 70.8 ± 15.7* | 1447 ± 204 | 648 ± 24.9* | 244 ± 27.0* |

| Stem cell factor (pg mL−1) | 68.2 ± 5.5* | 175.2 ± 14.7 | 110.8 ± 11.8* | 68.6 ± 3.1* |

| Eotaxin (pg mL−1) | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (pg mL−1) | 15.1 ± 6.8* | 382.2 ± 76.5 | 189.6 ± 51.3* | 17.8 ± 3.34* |

| Monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (pg mL−1) | 17.5 ± 8.2* | 314 ± 63.8 | 148.8 ± 45.9* | 12.2 ± 1.9* |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (pg mL−1) | 116.9 ± 22.2* | 230.2 ± 8.2 | 222.6 ± 13.9 | 199.2 ± 16.1 |

| Macrophage-derived chemokine (pg mL−1) | 12.1 ± 1.89* | 165.4 ± 56.0 | 35.4 ± 14.2* | 11.1 ± 1.7* |

| C-reactive protein (ng mL−1) | 0.5 ± 0.1* | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.70 ± 0.1* |

| Interleukin-1α (pg mL−1) | 41.8 ± 3.9* | 140.4 ± 13.5 | 103.8 ± 14.5 | 58.2 ± 4.4* |

| Interleukin-11 (pg mL−1) | 58.2 ± 15.6* | 142.0 ± 16.9 | 94.4 ± 7.5 | 60.4 ± 11.5* |

Efficacy of AQX-1125 and dexamethasone on BAL inflammatory markers in the airways of LPS challenged Sprague-Dawley rats. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the analyte concentrations (n = 5).

P < 0.05 shows a significant effect of AQX-1125 or dexamethasone compared to the vehicle-treated LPS group.

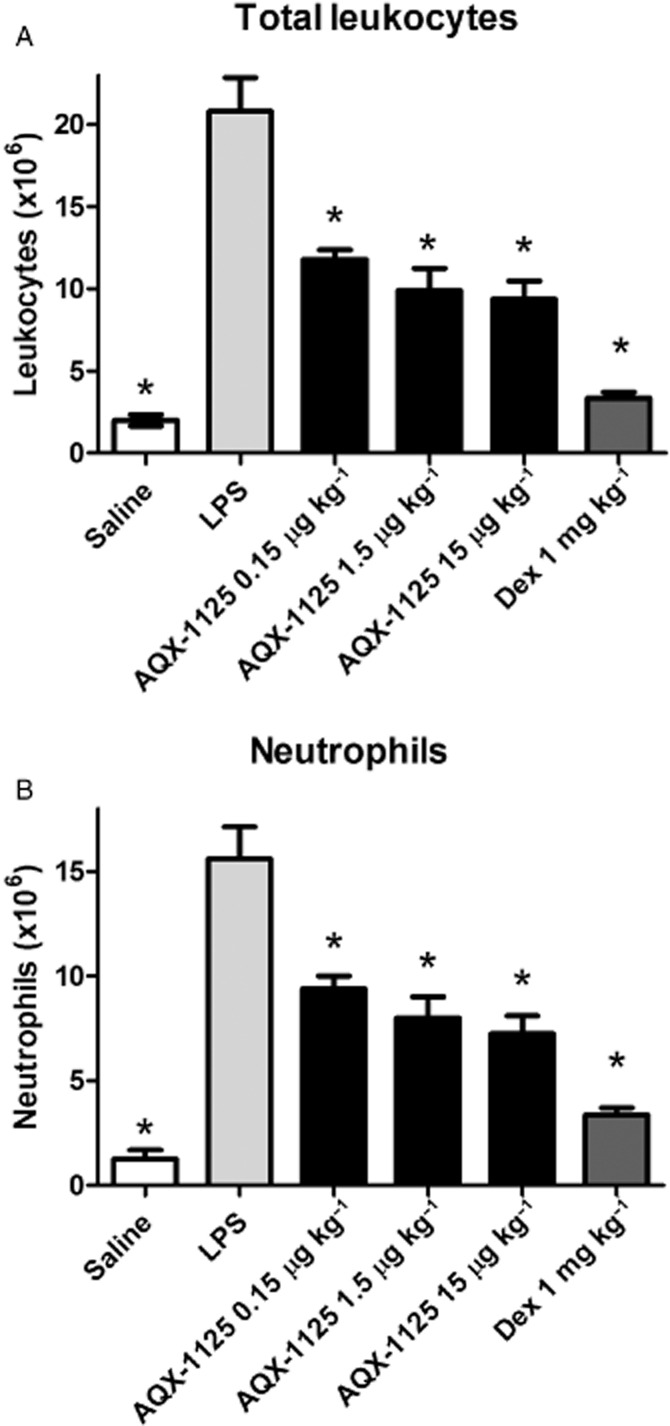

Aerosolized AQX-1125 was also shown to be efficacious in the same LPS experimental model, decreasing neutrophil infiltration at all three doses tested with a maximal inhibition of neutrophil infiltration (52%) observed at the top dose of 15 μg kg−1 (P < 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Efficacy of aerosolized AQX-1125 on total leukocyte and neutrophil infiltration of the airways in the rat LPS-induced lung inflammation model. Rats were administered AQX-1125 by aerosolization, once per day for 4 consecutive days, followed by LPS challenge 2 h after the last dose of test article. BAL was performed 24 h after LPS challenge. Data are presented as the absolute leukocyte counts (A) or neutrophil counts (B) (×106 cells). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 5–15), *P < 0.05 compared to vehicle-treated animals challenged with LPS.

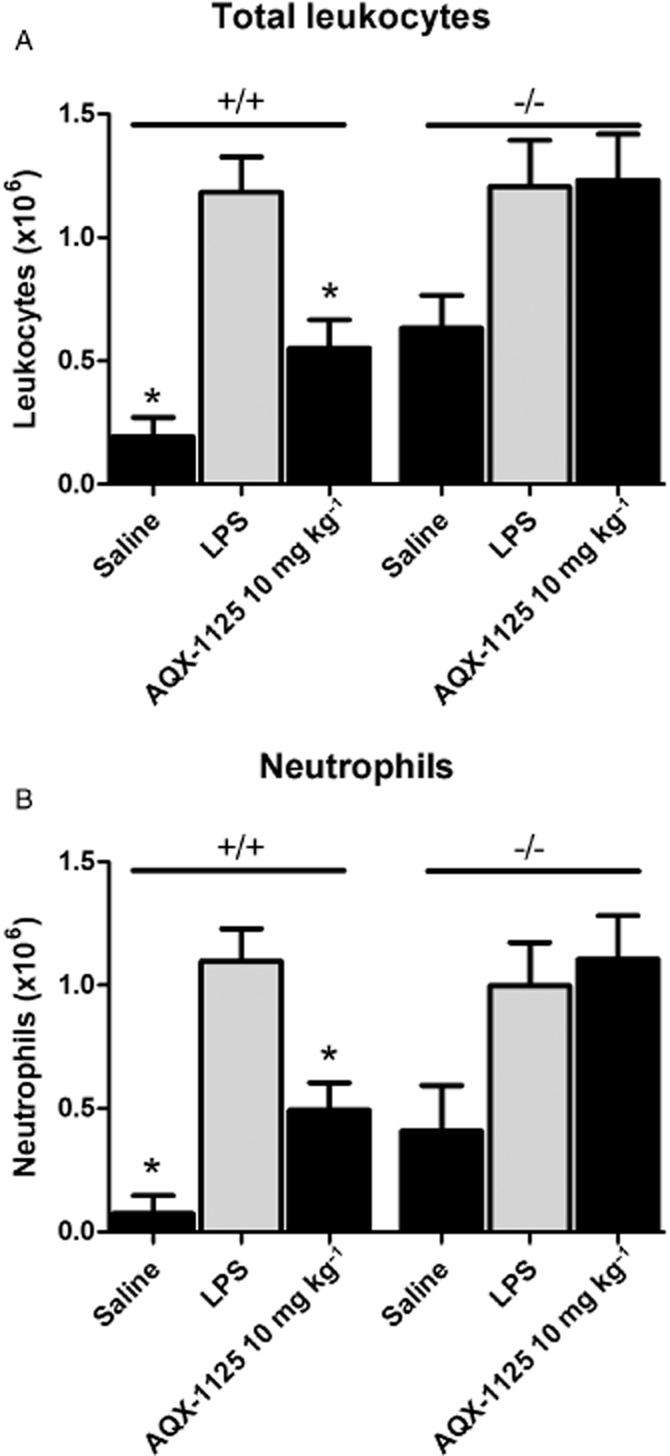

The SHIP1 dependance of AQX-1125 was demonstrated in an LPS airway inflammation model in SHIP1+/+ and SHIP1−/− mice. Neutrophil infiltration was reduced by AQX-1125 treatment of the SHIP1+/+ mice by 59 ± 11% (P < 0.05), but did not affect the SHIP1−/− mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Efficacy of AQX-1125 on total leukocyte and neutrophil infiltration of the airways of SHIP1+/+ and SHIP1−/− mice in an LPS-induced lung inflammation model. Mice were administered AQX-1125 by oral gavage, once per day for 4 consecutive days, followed by LPS challenge 2 h after the last dose of test article. BAL was performed 18 h after LPS challenge. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the absolute leukocyte counts (A) and the neutrophil counts (B) (×106 cells) (n = 6–8). *P < 0.05 denotes the anti-inflammatory effect of AQX-1125, compared to the response of the corresponding vehicle-treated control animals.

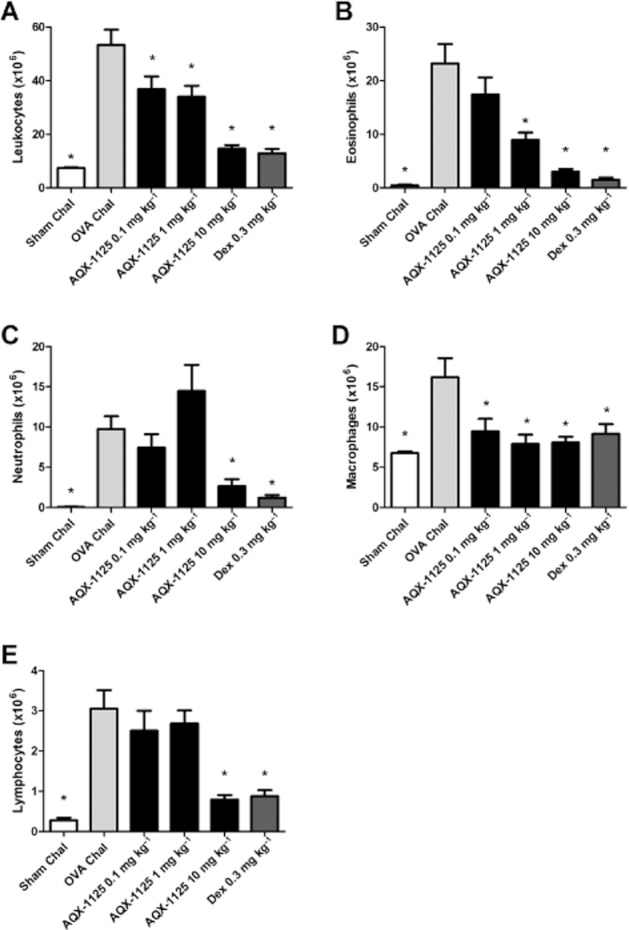

AQX-1125 exerts anti-inflammatory effects in OVA-induced airway inflammation

OVA challenge caused significant lung inflammation that resulted in increased total BAL cell numbers consisting largely of eosinophils and neutrophils (Figure 5, P < 0.05). AQX-1125 dose dependently reduced inflammatory cell counts in the BAL (P < 0.05). At 10 mg kg−1, its efficacy was comparable to that of the positive control compound dexamethasone at 0.3 mg kg−1 (Figure 5A–E). Analyte data from lung homogenates and BAL fluid samples taken after OVA challenge are presented in Table 2. Similar to the findings from the LPS model, AQX-1125 decreased the production of multiple pro-inflammatory mediators, and exhibited a characteristic response pattern that was different from that of the glucocorticoid dexamethasone.

Figure 5.

Efficacy of AQX-1125 in a Brown Norway rat OVA-induced lung inflammation model. Effects of AQX-1125 on (A) total leukocyte, (B) eosinophil, (C) neutrophil, (D) macrophage and (E) lymphocyte infiltration of the airways are shown. OVA sensitized rats were administered AQX-1125 by oral gavage, once per day for 3 consecutive days, followed by OVA challenge 2 h after the last dose of test article. BAL was performed 24 h after OVA challenge. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of absolute leukocyte counts (×106 cells) (n = 5–11), *P < 0.05 denotes the anti-inflammatory effect of AQX-1125 or of dexamethasone, compared to the response of the vehicle-treated control animals.

Table 2.

Effect of AQX-1125 and dexamethasone on BAL and lung tissue inflammatory mediator concentrations in the rat model of OVA-induced pulmonary inflammation

| PBS | OVA | AQX-1125 (10 mg kg−1) | Dexamethasone (0.3 mg kg−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAL fluid analytes | ||||

| CD40-L (pg mL−1) | 67.5 ± 9.5* | 121 ± 26.4 | 63.3 ± 16.2* | 84.0 ± 15.5 |

| Myeloperoxidase (ng mL−1) | 4.6 ± 2.1* | 43.6 ± 2.2 | 32.8 ± 3.6 | 19.1 ± 4.2* |

| Endothelin-1 (pg mL−1) | 5.2 ± 0.3* | 40.2 ± 14.1 | 5.7 ± 0.6* | 10.2 ± 0.8* |

| Fibrinogen (μg mL−1) | 15.0 ± 2.0* | 132 ± 22.0 | 23.3 ± 1.9* | 23.3 ± 1.9* |

| Stem cell factor (pg mL−1) | 23.9 ± 5.5* | 319 ± 124 | 23.0 ± 2.5* | 89.7 ± 4.9* |

| Eotaxin (pg mL−1) | 14.7 ± 1.1* | 198 ± 102 | 23.1 ± 1.2* | 32.2 ± 4.4 |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (pg mL−1) | 64.5 ± 13.5* | 427 ± 102 | 49.5 ± 2.5* | 38.8 ± 3.6* |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (pg mL−1) | 5.8 ± 0.5* | 20.8 ± 2.1 | 7.6 ± 0.8* | 6.2 ± 0.6* |

| Macrophage-derived chemokine (pg mL−1) | 253 ± 109* | 3291 ± 1287 | 420 ± 100* | 57.2 ± 14.9* |

| C-reactive protein (ng mL−1) | 0.40 ± 0.10* | 2.90 ± 0.50 | 0.40 ± 0.05* | 0.20 ± 0.05* |

| Interleukin-1α (pg mL−1) | 42.0 ± 3.7* | 130 ± 16.4 | 37.4 ± 3.8* | 31.6 ± 1.1* |

| Interleukin-11 (pg mL−1) | 26.1 ± 5.7* | 64.2 ± 8.6 | 14.8 ± 1.2* | 17.9 ± 7.1* |

| Lung homogenate analytes | ||||

| Fibroblast growth factor-9 (ng mL−1) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.01* | 1.4 ± 0.2* |

| Fibroblast growth factor-basic (ng mL−1) | 11.1 ± 1.1* | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.6* | 3.5 ± 0.3* |

| Stem cell factor (pg mL−1) | 133 ± 6* | 171 ± 9 | 106 ± 4* | 90 ± 5* |

| Eotaxin (pg mL−1) | 486 ± 49* | 1195 ± 56 | 706 ± 103* | 506 ± 34* |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (ng mL−1) | 0.5 ± 0.07* | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.08* | 0.3 ± 0.03* |

| Macrophage-derived chemokine (pg mL−1) | 425 ± 184* | 1217 ± 208 | 425 ± 55* | 139 ± 11* |

| Myeloperoxidase (ng mL−1) | 24.0 ± 1.5* | 66.6 ± 7.7 | 31.8 ± 3.6* | 29 ± 1.8* |

| Interleukin-1α (pg mL−1) | 52.3 ± 5.5* | 94.1 ± 5.8 | 63.1 ± 7.7* | 65.7 ± 1.5* |

| Interleukin-2 (pg mL−1) | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 15.2 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3* | 25.2 ± 1.7* |

Efficacy of AQX-1125 on BAL and lung homogenate inflammatory markers in the airways of OVA sensitized and challenged Brown Norway rats treated with either the SHIP1 activator AQX-1125 or with dexamethasone. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the analyte concentrations (n = 4–5), *P < 0.05 shows a significant effect of AQX-1125 or dexamethasone compared to the vehicle-treated OVA group.

The therapeutic versus prophylactic efficacy of AQX-1125 (10 mg kg−1) was assessed where AQX-1125 was either administered once daily on 3 consecutive days, once every 2 h before challenge, once every 2 h after challenge or once every 8 h after challenge. BAL was performed and absolute and differential leukocyte cell counts were determined (Table 3). AQX-1125 (10 mg kg−1) given once daily for 3 days prior to challenge or once every 2 h prior to challenge significantly decreased the airway infiltration of total leukocytes and, more specifically, eosinophils following OVA challenge (P < 0.05). A single dose of AQX-1125 given 2 h after challenge had no statistically significant effect on airway infiltration by any cell type (P > 0.05). A single dose of AQX-1125 given 8 h after challenge did not suppress total cell infiltration but significantly reduced eosinophilia (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Efficacy of AQX-1125 in the Brown Norway rat ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation model

| Group | Total cells (×106) | Eosinophils (×106) | Macrophages (×106) | Lymphocytes (×106) | Neutrophils (×106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 8.7 ± 1.1* | 0.4 ± 0.1* | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0* |

| OVA | 24.3 ± 2.7 | 14.2 ± 1.5 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.9 ± 0.9 |

| AQX-1125 (three doses prior to challenge) | 16.1 ± 1.2* | 7.9 ± 1.0* | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| AQX-1125 (2 h pre-challenge) | 16.6 ± 1.8* | 8.8 ± 1.0* | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.6 |

| AQX-1125 (2 h post-challenge) | 20.0 ± 1.2 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| AQX-1125 (8 h post-challenge) | 18.6 ± 1.6 | 7.2 ± 1.1* | 9.5 ± 1.7 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.8 |

AQX-1125 was administered orally at a dose of 10 mg kg−1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of absolute leukocyte counts (×106 cells) (n = 6–10), *P < 0.05 shows a significant effect of AQX-1125 compared to the vehicle-treated OVA group.

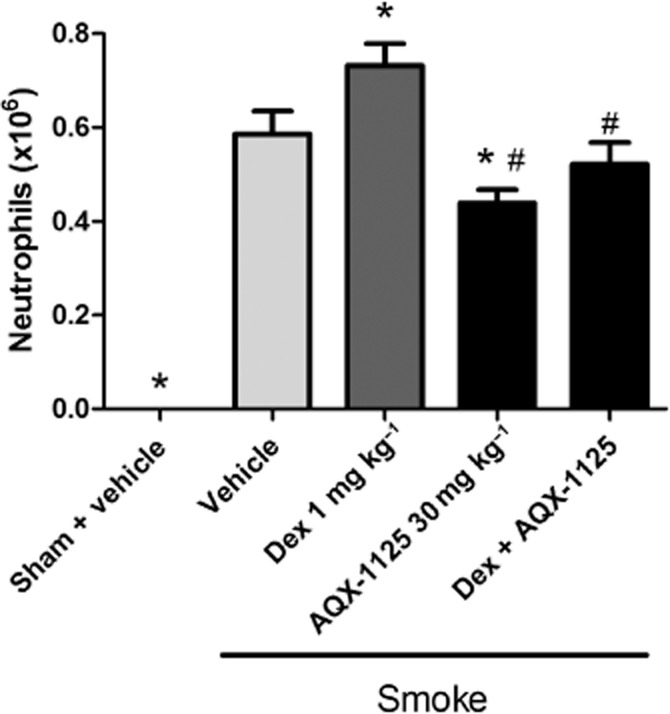

Effect of AQX-1125 in a cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation model

Cigarette smoke caused significant lung inflammation, resulting in increased BAL neutrophil numbers as shown in Figure 6 (P < 0.01). AQX-1125 (30 mg kg−1) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the BAL neutrophil number compared with the smoke control. Dexamethasone treatment significantly (P < 0.05) increased the BAL neutrophil number compared with the smoke control. The combination of 30 mg kg−1 AQX 1125 and 1 mg kg−1 dexamethasone significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the BAL neutrophil numbers compared with dexamethasone treatment alone.

Figure 6.

Efficacy of AQX-1125, dexamethasone (Dex) or AQX-1125 and Dex on neutrophil infiltration of the airways in a cigarette smoke-induced mouse lung inflammation model. Mice were administered AQX-1125 by oral gavage, once per day for 15 consecutive days. Two hours after the second dose of test article, mice were exposed to cigarette smoke, which continued three times a day for 14 days. BAL was performed on day 15 and data are presented as the mean ± SEM of absolute neutrophil counts (×106 cells) (n = 8), *P < 0.05 denotes the anti-inflammatory effect compared to vehicle; #P < 0.05 denotes significant effect of AQX-1125 compared to the effect of dexamethasone.

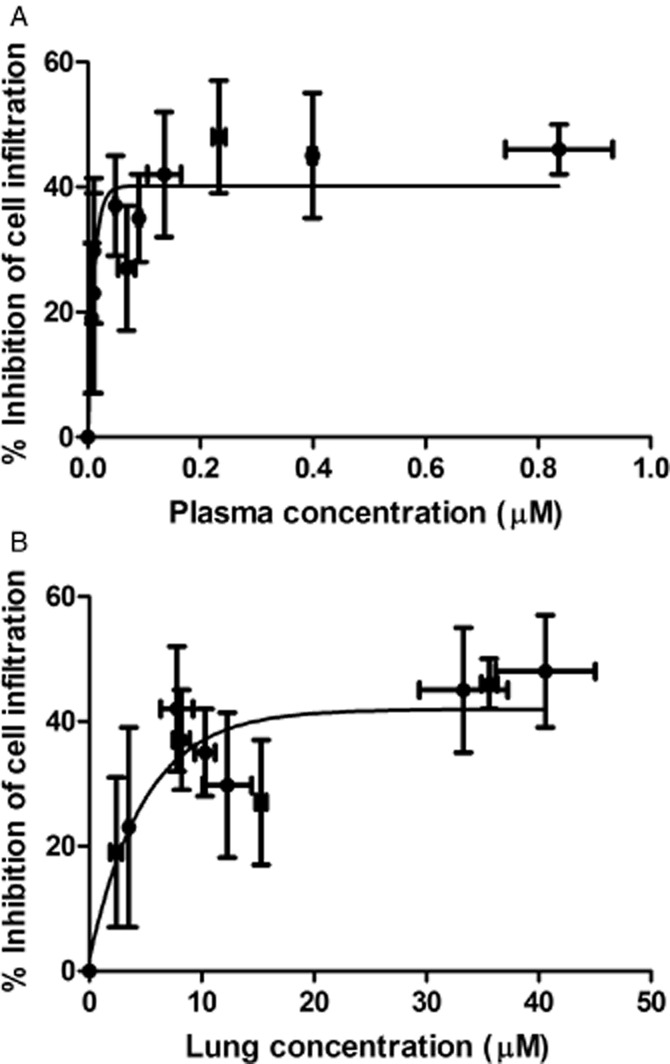

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic assessment of AQX-1125 in the OVA-induced airway inflammation model

The lung and plasma threshold concentrations of AQX-1125 necessary to achieve anti-inflammatory effects were determined in the Brown Norway rat OVA-induced airway inflammation model. As shown in Figure 7, AQX-1125 achieved a maximal effect with a plasma concentration >0.2 μM or a lung concentration of 10–30 μM at time of challenge. Increasing the plasma or lung concentrations above these values did not further enhance the efficacy of AQX-1125.

Figure 7.

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship of AQX-1125 in a Brown Norway rat OVA-induced lung inflammation model. Effects of AQX-1125 on total leukocyte infiltration of the airways are shown plotted against the corresponding plasma (A) or lung concentrations (B). OVA-sensitized rats were administered test article by oral gavage, once per day for 3 consecutive days, followed by OVA challenge 2, 4, 8, 24 or 48 h after the last dose of test article. BAL was performed 24 h after OVA challenge. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM absolute leukocyte counts (×106 cells), plasma concentrations (μM) or lung concentrations (μM, i.e. μmol equiv kg−1 tissue).

Discussion

SHIP1 has been reported to play a critical role in regulating leukocyte activation and chemotaxis, with the introduction of constitutively active SHIP1 into SHIP1-deficient cells resulting in suppression of the chemotactic response (Kim et al., 1999; Sattler et al., 2001; Mancini et al., 2002; Wain et al., 2005; Nishio et al., 2007). In the previous paper in this series, the SHIP1 activator, AQX-1125, was shown to be a potent inhibitor of in vitro leukocyte chemotaxis (Stenton et al., 2013) and cell function. Consistent with this, the current findings confirm the in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of AQX-1125, demonstrating a reduction in the infiltration of inflammatory cells (eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages), inflammatory mediator production and oedema formation in several models of inflammation in the skin and the lung.

These effects of the SHIP1 activator are consistent with the known role of SHIP1 in allergic responses and inflammatory lung diseases. First, SHIP1−/− mice exhibit a progressive and severe pulmonary inflammation, governed by the pulmonary infiltration of macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils (Helgason et al., 1998; Oh et al., 2007). These animals also show signs of mucous hyperplasia, airway epithelial hypertrophy and subepithelial fibrosis (Helgason et al., 1998; Oh et al., 2007). These pathological changes are accompanied by exaggerated production of Th2 cytokines and chemokines, including IL-4, IL-13, eotaxin and monocyte chemotactic protein-1, in the lung (Helgason et al., 1998; Oh et al., 2007). Second, SHIP1−/− mice respond to various pro-inflammatory stimuli with a highly exacerbated pro-inflammatory response in the lung. For instance, peptidoglycan-induced pulmonary inflammation (neutrophil infiltration into the lung and pulmonary extravasation) is much more severe in SHIP1−/− mice than in the corresponding wild-type controls (Strassheim et al., 2005). Third, when mast-cell-deficient mice are reconstituted with SHIP1−/− mast cells, there is a markedly exacerbated passive systemic anaphylaxis and an increased severity of OVA-induced allergic pulmonary inflammation as compared to mast-cell-deficient mice that are reconstituted with SHIP1 proficient mast cells (Haddon et al., 2009). Interestingly, the exacerbated pro-inflammatory phenotype of SHIP1 appears to develop in C57.SHIP1−/− mice, but not in BALB.SHIP1−/− mice, consistently with the importance of genetic background in the development of pulmonary allergic/inflammatory diseases (Maxwell et al., 2011). The specificity of AQX-1125 to SHIP1 is highlighted by the finding that the compound does not reduce the number of inflammatory cells in the BAL of SHIP1−/− mice.

Pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution studies showed that AQX-1125 is present at high concentrations in the lung tissue (Stenton et al., 2013). Oral dosing at 3–10 mg kg−1 as used in vivo, achieved the concentrations needed for in vitro anti-chemotactic and anti-inflammatory effects as described in Stenton et al., (2013). Moreover, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic investigations in the OVA model determined that the threshold lung concentration of AQX-1125 necessary to inhibit inflammatory cell infiltration into the BAL is approximately 10 μM, a concentration where AQX-1125 exerts significant anti-inflammatory/anti-chemotactic activity in vitro.

AQX-1125 demonstrated a potent anti-inflammatory effect in a mouse PCA model by reducing cutaneous oedema. Moreover AQX-1125 had a significant anti-inflammatory effect in two distinct models of lung inflammation: LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation and OVA-induced allergic pulmonary inflammation in vivo, inhibiting both cell infiltration of the lung and cytokine production. Recent studies characterized the pathways involved in the regulation of cytokine production by SHIP1 in immune cells and implicated a role for IκB kinase α/β and IFN regulatory factor 3 activation (Cekic et al., 2011). However, it must be emphasized that both in vitro (Stenton et al., 2013) and in vivo (LPS and OVA models of lung inflammation), the net production of cytokines and chemokines and other inflammatory mediators is the result of complex interactions between multiple interacting cell types (Leff et al., 1991; Ajuebor et al., 1999; Vignola et al., 2002; Lambrecht and Hammad, 2003). Therefore, the efficacy of AQX-1125 likely involves the simultaneous modulation of multiple interacting pathways and cell types.

In addition to the LPS and OVA models, AQX-1125 was also effective at reducing pulmonary neutrophilia in the murine model of smoke-induced lung inflammation where dexamethasone did not exert any protective effects. The lack of effect by dexamethasone in this model has previously been reported (Medicherla et al., 2008; Marwick et al., 2009; To et al., 2010) and is consistent with the limited clinical efficacy of glucocorticoids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Marwick and Chung, 2010). AQX-1125 remained effective in reducing pulmonary neutrophilia in the presence of the glucocorticoid. These data are interesting in the context of recent studies showing that PI3K inhibitors also maintain their efficacy in the presence of glucocorticoids in a cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation model (Marwick et al., 2009). The relative comparative efficacy of these different approaches and the ultimate clinical utility of SHIP1 activation as a potential therapeutic approach in humans remain to be determined in future clinical studies.

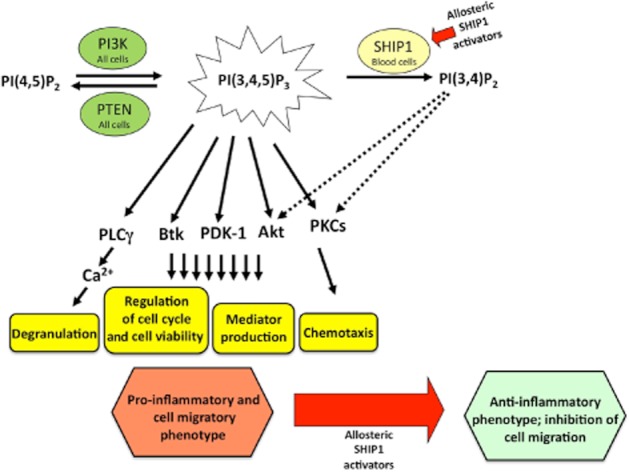

In summary, AQX-1125, a member of a novel class of pharmacological SHIP1 activators, inhibits cutaneous oedema, as well as leukocyte accumulation and pro-inflammatory mediator release into the BAL fluid in rodent models of allergy and pulmonary inflammation in vivo. We conclude that SHIP1 activation has significant anti-inflammatory potential with multiple potential mechanisms of action as outlined in Figure 8. Additional preclinical and clinical studies are needed to evaluate the clinical therapeutic potential of AQX-1125 in inflammation.

Figure 8.

Proposed molecular mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory effects of allosteric SHIP1 activation. PI3Ks are a family of critical intracellular enzymes that catalyse the addition of a phosphate molecule specifically to the 3-position of the inositol ring to generate the D3 phosphoinositides including PIP3. PI3K initiates signalling pathways that regulate, among others, vesicular trafficking, cell proliferation, differentiation, protein translation, proinflammatory mediator production, cell survival, actin cytoskeletal rearrangements and cell migration. Two major PIP3 degradation pathways have been defined, namely, the 3′-phosphatase phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN; deleted on chromosome 10; ubiquitously expressed) and 5′-phosphatase SHIP1 (expressed primarily in haematopoietic cells), which convert PIP3 to PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2, respectively. Although the PTEN pathway is generally considered a constitutively active pathway, SHIP1 activity is dynamically regulated by the cellular environment. Pharmacological activation of SHIP1 selectively redirects PIP signalling in haematopoietic cells from PIP3-mediated responses to PI(3,4)P2-mediated responses. Although PIP3 promotes degranulation, pro-inflammatory mediator production and chemotaxis via a variety of complex intracellular signalling pathways (solid arrows), PI(3,4)P2 modulates these responses differentially (dashed arrows). Consequently, after SHIP1 activation, the cellular response is shifted to an anti-inflammatory phenotype as evidenced by reduced activation of Akt signalling, attenuated inflammatory mediator production and inhibition of chemotaxis. Akt, protein-serine/threonine kinase activated by PIP3; Btk, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; PDK-1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; PIP, phosphatidylinositol phosphate; PLCγ, phospholipase C gamma; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Murigenics (Vallejo, CA), Ricerca Biosciences (Bothell, WA), PharmaLegacy Laboratories (Shanghai, China) and Pneumolabs (London, UK) for their expertise in the work outlined herein. We are also grateful for Dr. Gerry Krystal (University of British Columbia) for providing SHIP1+/+ and SHIP1−/− mice for these studies.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- DNP-HSA

dinitrophenyl-human serum albumin

- IT

intratracheal

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PCA

passive cutaneous anaphylaxis

- SHIP1

SH2-containing inositol-5′-phosphatase 1

Conflict of interest

All authors of this article are employees, former employees, consultants or stockholders of Aquinox Pharmaceuticals, a for-profit organization involved in the development of small-molecule SHIP1 activators as potential human therapeutic agents.

References

- Ajuebor MN, Das AM, Virág L, Flower RJ, Szabo C, Perretti M. Role of resident peritoneal macrophages and mast cells in chemokine production and neutrophil migration in acute inflammation: evidence for an inhibitory loop involving endogenous IL-10. J Immunol. 1999;162:1685–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Schimmer B, Schimmer RC, Warner RL, Schmal H, Nordblom G, Flory CM, et al. Expression of lung vascular and airway ICAM-1 after exposure to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:344–352. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.3.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell MA, Patel HJ, McCluskie K, Wong S, Leonard T, Yacoub MH, et al. PPAR-gamma agonists as therapy for diseases involving airway neutrophilia. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:18–23. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00098303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cekic C, Casella CR, Sag D, Antignano F, Kolb J, Suttles J, et al. MyD88-dependent SHIP1 regulates proinflammatory signaling pathways in dendritic cells after monophosphoryl lipid A stimulation of TLR4. J Immunol. 2011;186:3858–3865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddon DJ, Antignano F, Hughes MR, Blanchet MR, Zbytnuik L, Krystal G, et al. SHIP1 is a repressor of mast cell hyperplasia, cytokine production, and allergic inflammation in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183:228–236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason CD, Damen JE, Rosten P, Grewal R, Sorensen P, Chappel SM, et al. Targeted disruption of SHIP leads to hemopoietic perturbations, lung pathology, and a shortened life span. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1610–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer JG, Cummins DJ, Edmonds BT. Multiplex proteomic approaches to sepsis research: case studies employing new technologies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2005;2:669–680. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WG, Park MY, Maubert M, Engelman RW. SHIP deficiency causes Crohn's disease-like ileitis. Gut. 2011;60:177–188. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Helgason CD, Yew S, Humphries RK, et al. Altered responsiveness to chemokines due to targeted disruption of SHIP. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1751–1759. doi: 10.1172/JCI7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. The other cells in asthma: dendritic cell and epithelial cell crosstalk. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff AR, Hamann KJ, Wegner CD. Inflammation and cell-cell interactions in airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:L189–L206. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.260.4.L189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini A, Koch A, Wilms R, Tamura T. The SH2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase (SHIP)-1 is implicated in the control of cell-cell junction and induces dissociation and dispersion of MDCK cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:1477–1484. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwick JA, Chung KF. Glucocorticoid insensitivity as a future target of therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:297–309. doi: 10.2147/copd.s7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwick JA, Caramori G, Stevenson CS, Casolari P, Jazrawi E, Barnes PJ, et al. Inhibition of PI3Kdelta restores glucocorticoid function in smoking-induced airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:542–548. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1570OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell MJ, Duan M, Armes JE, Anderson GP, Tarlinton DM, Hibbs ML. Genetic segregation of inflammatory lung disease and autoimmune disease severity in SHIP-1-/- mice. J Immunol. 2011;186:7164–7175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicherla S, Fitzgerald MF, Spicer D, Woodman P, Ma JY, Kapoun AM, et al. P38alpha-selective mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor SD-282 reduces airway inflammation in a subchronic model of tobacco smoke-induced airway inflammation. J Pharmacol Exper Ther. 2008;324:921–929. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio M, Watanabe K, Sasaki J, Taya C, Takasuga S, Iizuka R, et al. Control of cell polarity and motility by the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase SHIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ncb1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SY, Zheng T, Bailey ML, Barber DL, Schroeder JT, Kim YK, et al. Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 1 deficiency leads to a spontaneous allergic inflammation in the murine lung. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CJ, Ming-Lum A, Nodwell M, Ghanipour A, Yang L, Williams DE, et al. Small-molecule agonists of SHIP1 inhibit the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2007;110:1942–1949. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M, Verma S, Pride YB, Salgia R, Rohrschneider LR, Griffin JD. SHIP1, an SH2 domain containing polyinositol-5-phosphatase, regulates migration through two critical tyrosine residues and forms a novel signaling complex with DOK1 and CRKL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2451–2458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenton GR, Kim MK, Nohara O, Chen CF, Hirji N, Wills FL, et al. Aerosolized Syk antisense suppresses Syk expression, mediator release from macrophages, and pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;164:3790–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenton GR, Mackenzie LF, Tam P, Cross JL, Harwig C, Raymond J, et al. Characterization of AQX-1125, a small molecule SHIP1 activator. Part 1. Effects on inflammatory cell activation and chemotaxis in vitro and pharmacokinetic characterization in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:1506–1518. doi: 10.1111/bph.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassheim D, Kim JY, Park JS, Mitra S, Abraham E. Involvement of SHIP in TLR2-induced neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2005;174:8064–8071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima R, Akiyama H, Akasaka R, Goda Y, Toyoda M, Sawada J. Simple spectrophotometric analysis of passive and active ear cutaneous anaphylaxis in the mouse. Toxicol Lett. 1998;95:109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To Y, Ito K, Kizawa Y, Failla M, Ito M, Kusama T, et al. Targeting phosphoinositide-3-kinase-delta with theophylline reverses corticosteroid insensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:897–904. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0937OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignola AM, La Grutta S, Chiappara G, Benkeder A, Bellia V, Bonsignore G. Cellular network in airways inflammation and remodeling. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2002;3:41–46. doi: 10.1053/prrv.2001.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos R, Bozinovski S, Jones JE, Powell J, Gras J, Lilja A, et al. Differential protease, innate immunity, and NF-kappaB induction profiles during lung inflammation induced by subchronic cigarette smoke exposure in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:931–945. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00201.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wain CM, Westwick J, Ward SG. Heterologous regulation of chemokine receptor signaling by the lipid phosphatase SHIP in lymphocytes. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]