Abstract

The tobacco whitefly Bemisia tabaci is one of the most devastating pests worldwide. Current management of B. tabaci relies upon the frequent applications of insecticides. In addition to direct mortality by typical acute toxicity (lethal effect), insecticides may also impair various key biological traits of the exposed insects through physiological and behavioral sublethal effects. Identifying and characterizing such effects could be crucial for understanding the global effects of insecticides on the pest and therefore for optimizing its management in the crops. We assessed the effects of sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of four widely used insecticides on the fecundity, honeydew excretion and feeding behavior of B. tabaci adults. The probing activity of the whiteflies feeding on treated cotton seedlings was recorded by an Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG). The results showed that imidacloprid and bifenthrin caused a reduction in phloem feeding even at sublethal concentrations. In addition, the honeydew excretions and fecundity levels of adults feeding on leaf discs treated with these concentrations were significantly lower than the untreated ones. While, sublethal concentrations of chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan did not affect feeding behavior, honeydew excretion and fecundity of the whitefly. We demonstrated an antifeedant effect of the imidacloprid and bifenthrin on B. tabaci, whereas behavioral changes in adults feeding on leaves treated with chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan were more likely caused by the direct effects of the insecticides on the insects' nervous system itself. Our results show that aside from the lethal effect, the sublethal concentration of imidacloprid and bifenthrin impairs the phloem feeding, i.e. the most important feeding trait in a plant protection perspective. Indeed, this antifeedant property would give these insecticides potential to control insect pests indirectly. Therefore, the behavioral effects of sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid and bifenthrin may play an important role in the control of whitefly pests by increasing the toxicity persistence in treated crops.

Keywords: ecotoxicology, Electrical Penetration Graph, feeding behavior; honeydew excretion; fecundity.

Introduction

Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), is one of the most damaging pests worldwide 1-5, including China where, since the 1990s, it has been largely affecting many major crops resulting in huge yield losses every year 6,7. In China, various classes of insecticides, such as organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids and, more recently, neonicotinoids are extensively used by growers to control B. tabaci 8. However, it has been reported that this pest has been difficult to control with conventional and newer insecticides because of the rapid development of resistance, as a result of overuse 8-11.

In field crops, lower insecticide concentrations usually occur after the initial insecticide application 12. These concentrations depend on how often insecticides are applied, how they are degraded by abiotic factors, such as rainfall, temperature and sunlight 12-14 and, in the case of systemic products, how fast is the plant growth 15-17. Under field conditions, B. tabaci would be exposed to sublethal and low-lethal doses of insecticides and may experience certain related sublethal effects. These are defined as physiological or behavioral trait modifications in individuals that survive an exposure to toxic compounds (notably insecticides) being the toxicant dose/concentration either sublethal or lethal 18. In addition to direct mortality by typical poisoning effects, pesticides may interfere with the feeding behavior of exposed insects by repellent, antifeedant, or reduced olfactory capacity effects 18-21.

Traditionally, pesticide efficacy assessment has relied on the determination of an acute median lethal dose/concentration. However, the effects of the newly developed insecticides are usually subtle, thus acute toxicity tests may only be a partial measure of the toxic effects 18,22. The impairment of key behavioral and physiological traits may strongly affect population dynamics 23. Therefore, accurate assessment of sublethal effects is crucial to acquire knowledge on the overall insecticide efficacy in controlling insect pest populations, as well as on their selectivity towards non-target organisms 18,24,25.

In the past three decades, a growing body of literature has aimed at assessing pesticide sublethal effects on various important biological traits of pests but, among them, feeding behavior has been scarcely investigated. Most plant-sucking organisms, notably homopteran insects, insert their piercing mouthparts (stylets) into the plant, imbibe fluids and expel honeydew. In previous studies, weight and honeydew excretion had usually been used as biological clues to assess effects of insecticides on feeding behaviors of homopteran insects, owing to the difficulties involved in measuring feeding quantitatively. The electronic penetration graph (EPG) technique was developed to record distinct phases of penetration and feeding activity in aphids 26. The principal component of this system is an electrical circuit made by a potted plant, an electrical resistor, a voltage source, the tested insect and various thin wire connections. When the insect mouthparts penetrate into the plant tissues, the circuit is completed and a fluctuating voltage originates different waveforms. The biological meanings of the various EPG waveforms were studied per each specific feeding behavioral trait for various plant-sucking insect species, whiteflies included 27-30. However, the majority of previous studies aimed at assessing insecticides effects on feeding behavior using the EPG technique were mainly conducted on aphids and brown planthopper, and few on the other homopteran insects, as well as on whiteflies. As phloem sap feeders, whiteflies penetrate their mouthparts into the leaf tissue, covering the distance from the epidermis to the phloem vessel intercellularly, and finally feed on substances in the sieve elements 31. Using the EPG technique, the mechanical stylet activity, the punctures of plant cells, the salivation and the active and passive ingestion can be easily recorded and distinguished 26. Inability to feed normally, as observed after the application of insecticides, should therefore be reflected in changes in the normal sequence of the EPG waveforms.

Mindful of this context, the aim of the present study is to assess the effects of sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of four insecticides (bifenthrin, carbosulfan, chlorpyrifos and imidacloprid) widely used to control whitefly pests 1,8-11 on B. tabaci adult females. For this we first conducted a concentration-response bioassay and then, evaluated the amount of insecticides to test, we investigated the sublethal effects on fecundity, honeydew excretion activity and on the feeding behavior by the electronic penetration graph (EPG) technique. The obtained results could be useful: (i) to acquire knowledge on the subtle mechanisms of action of the tested insecticides; and (ii) to assess the full insecticidal potential of these pesticides, since they may be able to slow down B. tabaci population growth at low concentration through sublethal effects.

Materials and Methods

Biological material

Adults of B. tabaci were collected from vegetable fields at the suburbs of Fuzhou city, Fujian Province, China, during July-August 2008. Bemisia tabaci pupae and adults were identified at the specific level using morphological characters. The population was assigned to the B biotype using molecular markers (cytochrome oxidase I) according to the method of Alon et al. 32. Individuals were used to establish a laboratory colony that was maintained for multiple generations on pesticide-free cotton plants, Gossypium hirsutum L., in a growth chamber (25±1 °C, 65±5% RH, and 14:10 L:D).

Insecticides

All the insecticides tested in the study were of technical grade. The neonicotinoid imidacloprid (96.8% purity) and the carbamate carbosulfan (95% purity) were provided by Changlong Chemical Limited Company (Jiansu, China), the pyrethroid bifenthrin (95% purity) was provided by Longdeng Chemical Limited Company (Jiansu, China) and the organophosphate chlorpyrifos (98.9% purity) was provided by Xinnong Chemical Limited Company (Zhejiang, China). Stock solutions of all the insecticides were first prepared in acetone, and then were diluted with purified water to obtain final concentrations of the active ingredients (a.i.) as follows: imidacloprid 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 ppm (parts per million); bifenthrin 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 ppm; chlorpyrifos 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 and 1600 ppm; carbosulfan 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 and 3200 ppm. Preliminary experiments were carried out to determine the range of insecticide concentrations, by exposing whitefly adults (from the population studied) to concentrations equal to recommended field application rates until observing mortality rates lower than 100%. The acetone concentration in the insecticidal solutions finally used was 10 ml l-1 or lower. The insecticides were chosen for the experiments since they are widely used in conventional cotton cultivations worldwide, mainly to control whitefly pests, and because they well represent four different insecticides families, i.e. those of neonicotinoids, pyrethroids, organophosphates and carbamates 1,8-11. These insecticide families impair different targets in exposed organisms: (i) the voltage-sensitive sodium channel on neuron membranes by pyrethroids, the acetylcholinesterase by the organophosphates and the carbamates, and (ii) the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by the neonicotinoids.

Insecticide exposure

For the concentration-mortality response and for the honeydew excretion and fecundity assessments, the whiteflies were exposed to dry residues of the various insecticides on cotton leaves. Cotton leaves were treated using the leaf-dip bioassay, and it was carried out following the methodology described by He et al. 33. Briefly, untreated cotton leaves were dipped for five seconds in the serial insecticide dilutions or in water plus acetone (as untreated control). Subsequently, the leaves were air-dried until all the insecticides solution droplets evaporated (1 h), and then leaf discs (35 mm of diameter) were cut and placed with their adaxial surface downwards onto agar in 35 mm-diameter Petri dishes. Whereas, to conduct the EPG assay (see below), entire 30-day old cotton seedlings were dipped in the insecticide solutions or in water plus acetone for five seconds. Cotton seedlings were air-dried for 1 h prior being used for the experiments.

Concentration-mortality response: LC50 and LC10

To obtain the concentrations to be used in further experiments, the concentration-mortality regression lines, the lethal concentration 50 (LC50) and 10 (LC10), the whiteflies were exposed for 24 h to the insecticide concentrations using the method previously described (see the Insecticide exposure section). 0-2-day old B. tabaci female adults per replicate were anesthetized with CO2 for two seconds, and then they were carefully transferred onto the leaf discs. Each Petri dish was then covered with a perforated lid and kept upside down in a growth chamber (25±1°C, 65±5% RH and 14:10 L:D). Mortality was recorded after 24h of exposure and the adults were considered dead when they remained immobile after being touched by a fine paintbrush. For each treatment (i.e. the four insecticides and the untreated control) and concentration tested, six replicates of 25 whiteflies were carried out.

Sublethal effects on honeydew excretion and on fecundity

To assess the effects of the insecticides on two important B. tabaci biological traits, i.e. honeydew excretion and egg laying activity, a sublethal concentration (inducing no significant mortality when compared to the untreated control 18) and a low-lethal concentration (< 40% mortality after 24-h of exposure) of each insecticides were used. These concentrations were chosen based on results of the section Concentration-mortality response. More specifically, we tested 5 and 20 ppm of imidacloprid, 10 and 40 ppm of bifenthrin, 50 and 200 ppm of chlorpyrifos, and 100 and 400 ppm of carbosulfan. The whiteflies were exposed to the insecticides using the methodology described above with the exception that the dishes were placed upside down on filter paper imbibed in ethanol solutions containing 0.1% bromocresol green. This system allows estimating the deposited honeydew, since bromocresol green produces blue spots where honeydew droplets are deposited with their size (surface) representing the amount of honeydew secreted by the tested insects 34. After 24 h of insecticides exposure, the area of blue spots on the filter paper was determined, and the adult mortality and the number of laid eggs were recorded. Five replicates of 0-2-day old adult females, previously starved for 2 h, for each treatment and concentration were carried out.

Sublethal effects on feeding behavior: EPG recording and studied parameters

The feeding behavior of the whiteflies exposed to plants treated with the sublethal and low lethal concentrations (see the Sublethal effects on fecundity and honeydew excretion section) was studied using the EPG DC (direct current) system technique 35 aiming at monitoring the whitefly stylet activity. For this we used an EPG Giga-4 amplifier (Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands) which was connected to a microcomputer. A gold wire (length: 2cm, diameter: 10µm) was attached, with water soluble silver glue, to the notum (thoracic dorsum) of the whiteflies, and then was connected to the EPG amplifier. The tested whiteflies were placed on the abaxial surface of the treated leaf disc. After 30 min of acclimation, the experiment was carried out inside a Farady cage to avoid electrical noises 36 in the laboratory (25±1°C, 65±5% RH). At least 20 0-2-day old females (previously starved for 2 h) per each insecticide and concentration were exposed to treated plants and tested using the EPG DC system. Behavioral observations were conducted between noon and 7.30pm. The EPG signal was recorded during 6h and the output signals were stored using the DI-720 Series® software (DataQ Instruments, Ohio, USA). The same software was also used to analyze the various EPG behavioral waveforms recorded during the experiments. The waveforms, previously described for B. tabaci and correlated with the probing activity of this particular species 28,35-37, were characterized as: (i) non-probing (waveform Np: stylets external to the plant); (ii) pathway phase (waveforms A, B C and pd [potential drop] reflecting an intercellular stylet pathway, intracellular feeding); (iii) xylem ingestion (waveform G); and (iv) phloem activities (waveform E [E1 and E2] representing salivation into phloem sieve elements and phloem ingestion).

Statistical analysis

The concentration-mortality response, the LC50 and the LC10 for B. tabaci, after 24 of exposure, were determined using a regression log-probit model 38. Dose-mortality relationships were considered valid (i.e. they fitted the observed data) when there was absence of significant deviation between the observed and the expected data (at the P<0.05 level). The surface of the honeydew deposits, the number of eggs laid (fecundity) and percentage of mortality of B. tabaci adults when exposed to sublethal and low-lethal insecticides concentrations was analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a HSD post hoc test for multiple comparisons with the control group. The same statistical method was used for analyzing the data obtained in the feeding behavior experiments i.e. time spent before the first probe (waveforms A, B, C, G and Pd) and phloem activities event (waveform E), total time spent in non-probing (waveform Np), in non- phloem (waveforms Pd + A + B + C) and in phloem activities (waveform E). All datasets were first tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using Kolmogorov-Smirnov D test and Cochran's test respectively, and transformed if needed. All analyses were conducted using SAS program 39.

Results

Determination of the LC50 and the LC10

Log-probit regression analyses of concentration-mortality data showed that, after 24 h of exposure to imidacloprid, bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan, the LC50 values were estimated at 39.60 ppm, 52.35 ppm, 337.04 ppm and 632.22 ppm, respectively. Whereas, The LC10 values at 24 h for imidacloprid, bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan were estimated at 5.28 ppm, 10.02 ppm, 55.18 ppm and 128.37 ppm, respectively. Therefore, 5 ppm, 10 ppm, 50 ppm and 100 ppm (~LC10) were selected as sublethal concentrations for further experiments for imidacloprid, bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan, respectively (Table 1). Absence of significant mortality in B. tabaci adults exposed to these concentrations was confirmed during the Honeydew excretion and egg production experiments (see below).

Table 1.

LC50 and LC10 values (with corresponding 95 % confidence intervals) for Bemisia tabaci adults after 24 h of exposure to insecticide-contaminated cotton leaves. Mortality in all control groups was always below 5 %. The results are presented as LC50 and LC10 with corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CI), chi-square results, degree of freedom (df) and regression equations.

| Imidacloprid | Bifenthrin | Chlorpyrifos | Carbosulfan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression equations | y=2.660+1.464x | y=1.932+1785x | y=0.878+1.631x | y=-0.184+1.861x |

| χ² (df) | 1.8617(4) | 0.8544 (3) | 0.8944 (3) | 0.6225 (3) |

| LC50 (ppm) 95% CI | 39.60 | 52.35 | 337.04 | 632.22 |

| 33.19-48.11 | 45.68-62.40 | 280.59-420.81 | 537.25-765.53 | |

| LC10 (ppm) 95% CI | 5.28 | 10.02 | 55.18 | 128.37 |

| 3.63-7.01 | 7.14-12.89 | 38.69-71.52 | 95.81-160.23 |

Honeydew excretion and egg production

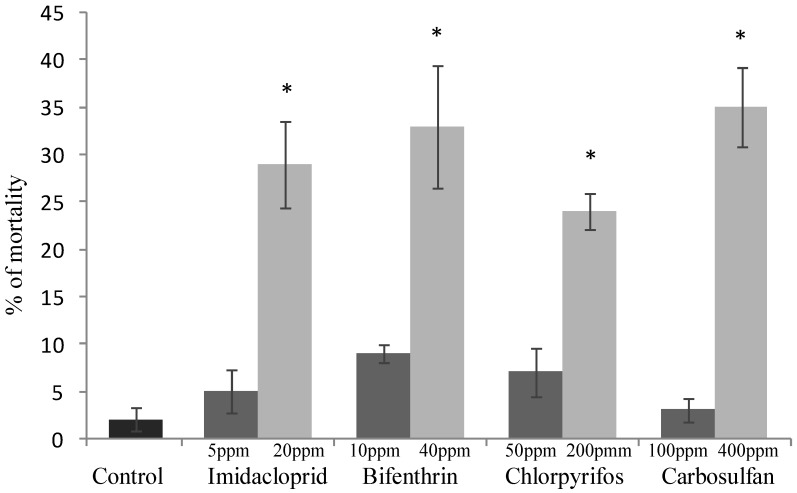

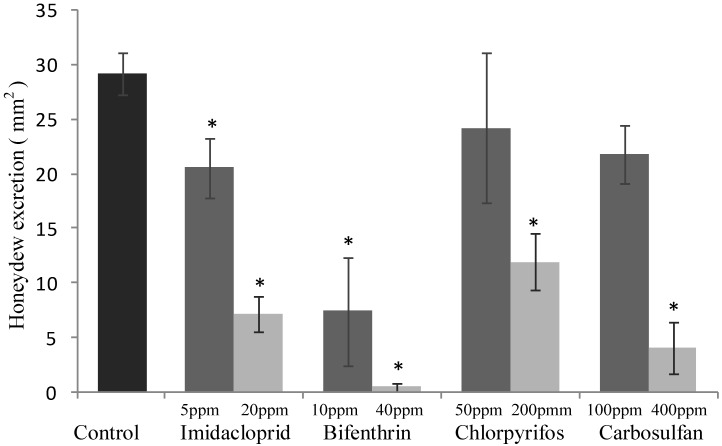

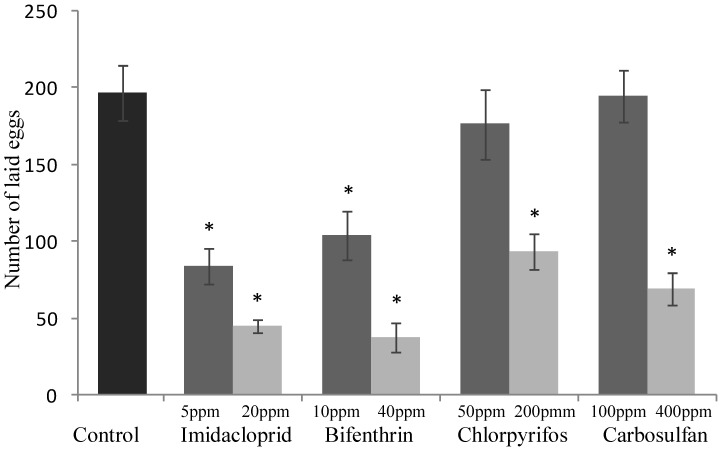

The sublethal concentrations caused mortality rates ranging from 3% to 9% and they were not significantly different from the mortality percentages recorded for the untreated control (F4,20 = 2.645; P =0.0638) (Fig. 1). The same concentrations caused a significant decrease of honeydew excretion only for imidacloprid and bifenthrin, 20.59 and 7.40 mm2, respectively (F4,20 = 4.512; P = 0.007) (Fig. 2). By contrast, sublethal concentrations of chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan did not significantly decrease honeydew secretion of B. tabaci. The same trend was observed for the fecundity; only the sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid and bifenthrin significantly reduced the number of eggs laid by adults (about by one third and a half, respectively) during the 24-h exposure period (F4,20 = 9.398; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Lethal effect of sublethal and low-lethal insecticide concentrations. Percentages (means ± SEM) of Bemisia tabaci females after 24 h of exposure to sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of the four tested insecticides. Means for treatment bearing asterisks differed from the untreated control at P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by HSD test.

Figure 2.

Sublethal effect on honeydew excretion of sublethal and low-lethal insecticide concentrations. Means (±SEM) of honeydew excretion deposited by Bemisia tabaci females, measured as blue spots size (mm2) on bromocresol green after 24 h of exposure to sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of the four tested insecticides. Means for treatment bearing asterisks differed from the untreated control at P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by HSD test.

Figure 3.

Sublethal effect on egg production of sublethal and low-lethal insecticide concentrations. Total number of laid eggs (means ± SEM) by Bemisia tabaci females after 24 h of exposure to sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of the four tested insecticides. Means for treatment bearing asterisks differed from the untreated control at P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by HSD test.

The mortality rates caused of the low-lethal concentrations ranged from 24% to 35% for chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan, respectively (Fig. 1), and the mortality caused by all the insecticides was significantly different from the untreated control one (F4,20 = 11.439; P <0.001). Honeydew excretion and egg production significantly decreased when B. tabaci adults were exposed to the low-lethal concentrations of all the tested insecticides (honeydew excretion: F4,20 = 40.114; P < 0.001. Egg production: F4,20 = 30.961; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2 and 3). The most detrimental chemical was bifenthrin that caused the lowest honeydew excretion and fecundity levels, 0.40 mm2 and 37.20 eggs laid, respectively. Although significantly different from the control, the results obtained with chlorpyrifos at 200 ppm were the highest, i.e. 11.90 mm2 of honeydew deposits and 93.20 laid eggs (Fig. 2 and 3).

Feeding behavior

In the 6-h period of recorded EPGs, we observed typical waveforms of B. tabaci feeding on cotton leaves 37, such as non-probing (waveform Np), pathway phase (waveforms A, B, C, and Pd), xylem ingestion (waveform G), and phloem activities (waveform E). However, since xylem ingestion occurred very rarely in the EPGs, it was not analyzed further.

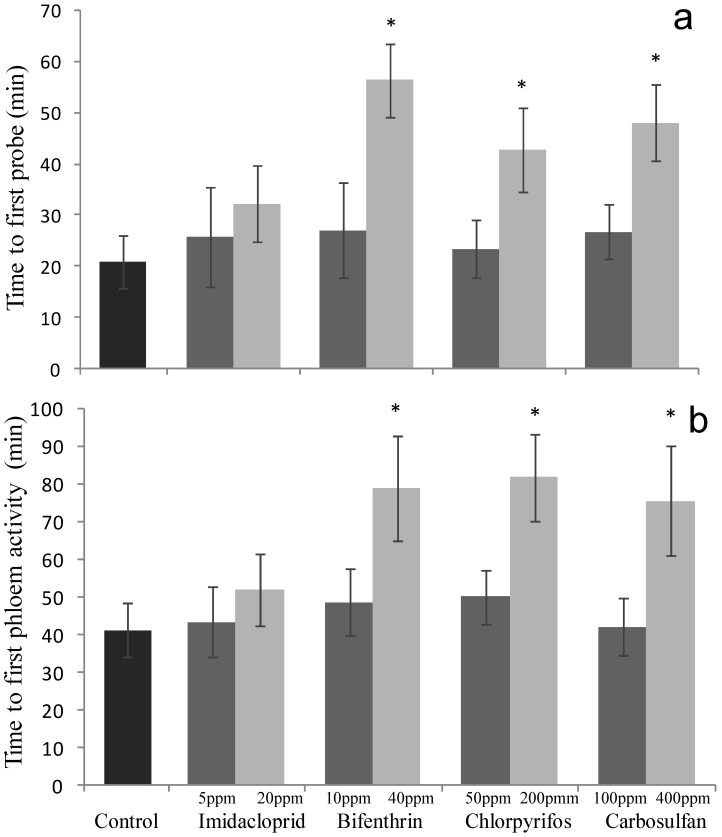

The time spent before the first probing event was significantly altered only after exposure to low-lethal concentrations of bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan (F4,95 = 4.44; P = 0.002) (Fig. 4a). In particular, when compared to the untreated control, the corresponding time intervals increased by 35.44, 21.84 and 27.1 minutes, respectively. By contrast, this trait was not significantly affected when exposing the whiteflies to sublethal concentrations of all the insecticides tested (F4,103 = 0.173; P = 0.952) (Fig. 4a). The same trend (i.e. only low-lethal concentrations of bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan caused significant effects) was recorded when analyzing the time spent before the first phloem feeding (F4,95 = 3.576; P = 0.009) (Fig. 4b). By contrast, sublethal concentrations of all the tested insecticides did not affect this parameter (F4,103 = 0.231; P = 0.920) (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Sublethal effect on feeding behavior of sublethal and low-lethal insecticide concentrations. Means (±SEM) of minutes spent by Bemisia tabaci females before the first (a) probing (waveforms A, B, C and Pd) and (b) phloem (waveform E) activities, during the 6-h behavioral bioassay conducted on leaves treated with sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of the four tested insecticides. Means for treatment bearing asterisks differed from the untreated control at P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by HSD test.

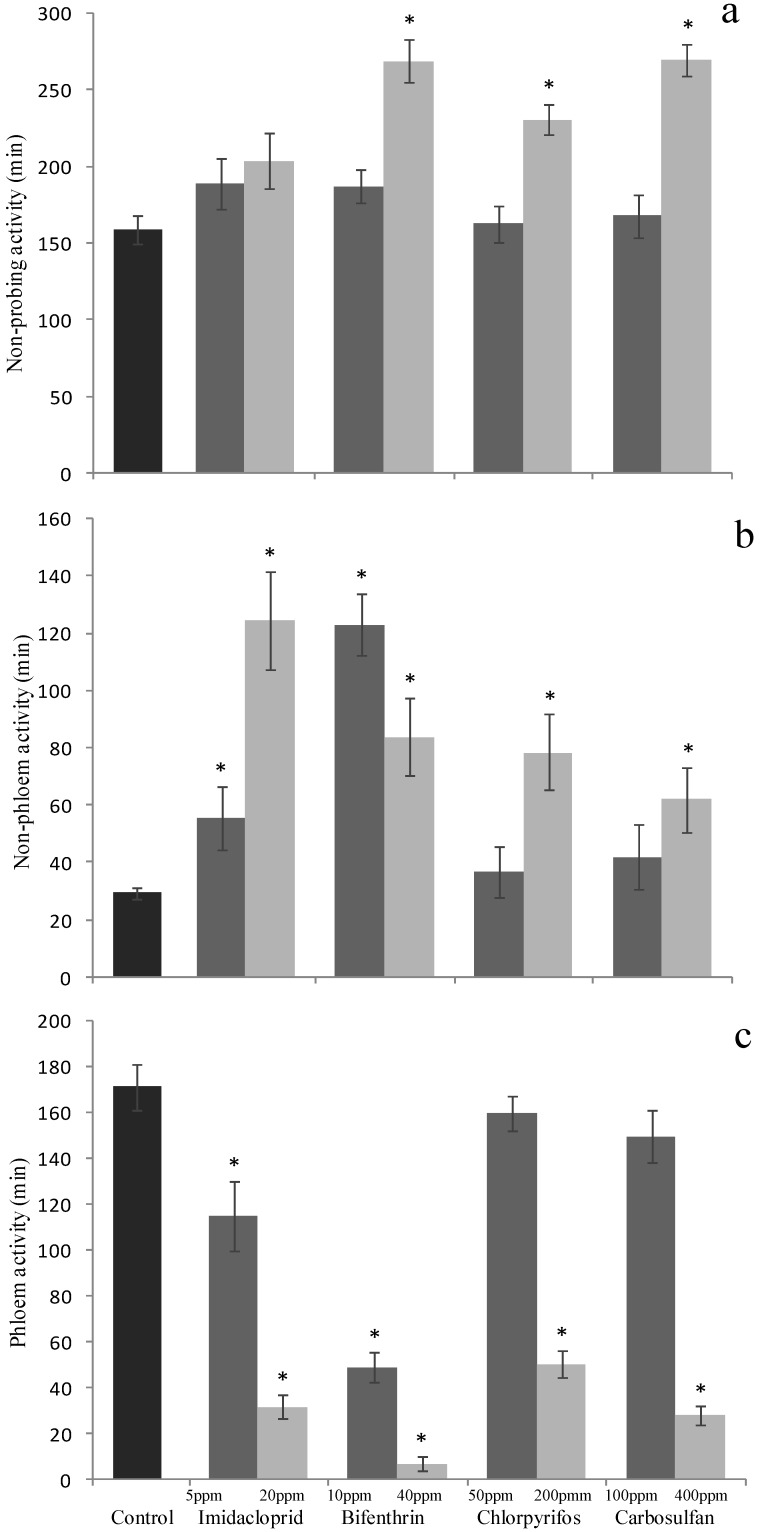

On the other hand, when the total durations (for the 6 h of observations) of the single traits of the B. tabaci feeding behavior were studied, sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid and bifenthrin both decreased the duration of the phloem activity (F4,103 = 16.821; P <0.001) (Fig. 5c) and increased the non-phloem activity durations (F4,103 = 35.637; P <0.001) (Fig. 5b), this resulting in a marked decrease of the overall feeding activities. The total duration of the non-probing behavior was not significantly affected by sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid and bifenthrin (F4,103 = 1.269; P = 0.287) (Fig. 5a). By contrast, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan at sublethal concentrations did not affect all these traits and the various recorded time intervals were similar to those recorded for the whiteflies exposed to insecticide-free cotton leaves (Fig. 5a, 5b and 5c).

Figure 5.

Sublethal effect on probing behavior of sublethal and low-lethal insecticide concentrations. Means (±SEM) of total time (minutes) spent by Bemisia tabaci in (a) non-probing (waveform Np), (b) non-phloem (waveforms A, B, C and Pd) and (c) phloem (waveform E) activities, during the 6-h behavioral bioassay on leaves treated with sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of the four tested insecticides. Means for treatment bearing asterisks differed from the untreated control at P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by HSD test.

The low-lethal concentrations of bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan significantly affected the duration of the non-probing (F4,95 = 17.02; P <0.001) (Fig. 5a), non-phloem (F4,95 = 17.305; P <0.001) (Fig. 5b) and phloem behaviors (F4,95 = 55.403; P <0.001) (Fig. 5c). The increase of durations of non-probing (chlorpyrifos: +72 min., bifenthrin and carbosulfan: + ~110 min.) and non-phloem activities (55, 49, 33 min. for bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan, respectively) caused a marked decrease of the feeding activity sensu stricto, i.e. of the phloem activities (-165, -121 and-143 minutes for bifenthrin, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan, respectively). Imidacloprid at the low-lethal dose did not affect significantly the non-probing behavior (Fig. 5a), but significantly increased the duration of non-phloem activity (+95 minutes) (Fig. 5b) and decreased the amount of time spent for phloem feeding (-140 minutes) (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

In addition to direct mortality induced by pesticides, insects that survive to an exposure to these products may experience behavioral and/or physiological alterations 18. This is particularly true in the case of newly developed insecticide which has a slower mode of action and may produce a greater degree of sublethal effects rather than acute ones 18, 22-24. In the present study we assessed the effects of insecticides belonging to four different chemical families and we provided experimental evidence of sublethal effects induced by the four insecticides on B. tabaci adults. Interestingly, imidacloprid and bifenthrin caused major sublethal effects on both reproduction and feeding-related traits even when applied at sublethal concentrations, i.e. at rates of insecticides that do not cause significant insect mortality. By contrast, chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan affected physiological and behavioral traits only when B. tabaci were exposed to higher (low-lethal) concentrations. Interestingly, no stimulatory effects of low concentrations were found in any of the tested insecticide. This phenomenon, known as hormesis, has been proved to occur on both pest and natural enemy insects after the exposure to low doses of some insecticides, such as imidacloprid 25,40. The obtained results show that the effects of the insecticides can strongly vary depending upon various factors, such as the endpoint considered (mainly lethal, physiological and behavioral), the insecticide chemical family and the insecticide concentration considered.

Severe detrimental effects on the whitefly fecundity were observed in individuals feeding on cotton leaves treated with the imidacloprid and bifenthrin at sublethal concentrations, and with all the tested insecticides at low-lethal concentrations. Reduced fecundity of the whitefly after feeding on leaves treated with sublethal concentration of imidacloprid is consistent with previous works studying other Hemipteran insect species. The fecundity of aphid species (Myzus persicae and M. nicotianae) and leafhopper species (Nephotettix cincticeps, N. lugens and N. virescens) was reduced by more than 50% after feeding on plants/leaves treated with sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid 41-43. Similar reproductive effects of pyrethroids had been also reported for mite Tetranychus urticae 44 and thrips Frankliniella occidentalis 45. Reproduction related traits have traditionally been the most sublethal parameter studied and represent one of the most important life-history when studying the insect population levels 13,18,21-23. Therefore, the obtained results may be of primary importance for the management of pests in crops.

Comparing the reductions in honeydew excretion of whitefly feeding on imidacloprid-, bifenthrin-, chlorpyrifos- and carbosulfan-treated leaves, it arises that honeydew excretion was decreased by imidacloprid and bifenthrin even when applied at sublethal concentration (i.e. LC10 in our study). In a previous study, imidacloprid gave similar results since the Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri) adults excreted significantly less honeydew, when they fed on citrus leaves treated systemically with lethal and sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid 46. By contrast, in our study, sublethal concentrations of chlorpyrifos and carbosulfan did not cause reduction in the honeydew excretion of whitefly adults remarkably. Furthermore, the decrease in honeydew excretion of whitefly adults feeding on leaves treated with low-lethal concentrations of chlorpyrifos (200 ppm) and carbosulfan (400 ppm) may be linked to the observed mortality and pre-lethal typical symptoms of poisoning by insecticides in arthropods. The results obtained for imidacloprid are in accordance with those of a previous study, in which, although female adults of B. tabaci preferred untreated leaf discs rather than the treated ones, the honeydew excretion was inhibited by 50% when whiteflies fed on leaves treated even with very low imidacloprid concentrations, i.e. 150- to 850-times lower than the LC50 47.

Honeydew excretion is a physiological process that originates from the feeding activity, since honeydew is expelled from the gut's terminal opening after that the mouthpart penetrates the phloem. Therefore, whitefly-feeding data, obtained with the EPG analysis, may help in understanding the mechanism of the antifeedant properties of the studied chemicals. Indeed, feeding behavior results were well correlated with the amount of honeydew secreted, since at sublethal concentrations only imidacloprid and bifenthrin caused significant behavioral changes of B. tabaci and, at low-lethal concentrations, all the tested insecticides impaired the feeding activity. Whiteflies exposed to sublethal concentrations did not delay their first phloem activities (Fig. 4b) and, after being in contact with the treated plant sap, they significantly reduced the phloem activity (Fig. 5c) and increased the non-phloem one (Fig. 5b). This clearly proves that the insecticides did not have repellency proprieties, since the insects were not repulsed by the treated leaves, while they act as antifeedant, i.e. decreasing the feeding of the pest. Similar antifeedant effects of imidacloprid have been reported on other plant sucking insects, such as the aphids M. nicotianae and M. persicae 27,41. Daniels et al. 29 and Cui et al. 30 also found that sublethal dose of thiamethoxam and IPP10 (a novel neonicotinoid), caused reduction in xylem and phloem feeding by Rhopalosiphum padi on wheat. Antifeedant activity of pyrethroids was reported for other sucking insects, such as mite T. urticae adults 44, and thrips F. occidentalis adults 45. For organophosphates and carbamates, carbosulfan at 0.5 ppm (LC50 2.9 ppm) and methiocarb at ≤5 ppm (LC50 52.6 ppm) suppressed the feeding of F. occidentalis. Methamidophos and monocrotophos also inhibited the feeding activity of immature instars of this thrip species at concentrations less than the LC10 45. By contrast, T. urticae behavior appeared to be unaffected by phosmet 44.

We assume that the antifeeding response of B. tabaci exposed to imidacloprid and bifenthrin may be related to the effects on the epipharyngeal chemoreceptors (through altered cibarial pump activity and overall decreased capacity to ingest xylem sap). Indeed, studies suggest a possible negative effect of another neonicotinoid, the thiamethoxam, on the cibarial pump in aphid species 30. This negative effect on the cibarial pump may be due to a neurotoxic effect on either the pharyngeal valve or the dilator muscles, which are innervated via the thoracic ganglion 48. Luo et al. 49 reported that toosendanin, a triterpenoid derivative, inhibits the sugar and the glucosinolate receptors in the epipharyngeal sensillum (the lateral styloconicum). McLean and Kinsey 26 also reported that negative stimulation of the gustatory epipharyngeal sensilla, which are located in the epipharyngeal gustatory organ, may initiate the relaxation of either the cibarial pump muscles or the pharyngeal valve, thus slowing ingestion and resulting in an antifeedant effect. Moreover, another hypothesis is plant composition changes induced by imidacloprid and bifenthrin, e.g. due to alterations in the amino acid composition, which could also inhibit ingestion by the whiteflies. Indeed, Wu et al. 50 found that, although the total free amino acid composition was not affected by the pesticide treatment, some amino acids were significantly altered after pesticide application, as exemplified by lower γ-aminobutyric acid, bisultap and jingganmycin in treated plants than that in the untreated ones.

Taken as a whole, the results show that aside from the lethal effect, sublethal concentration of imidacloprid and bifenthrin modify whitefly behavior by impairing phloem feeding, the most important feeding trait in a plant protection perspective. Indeed, this pest causes direct crop damage through phloem feeding (sap suction) and indirectly through honeydew contamination and associated fungal growth, or by vectoring several plant viruses plant injuries (infected saliva inoculation) 1, 3 and the successful virus transmission is often enhanced by an increase of B. tabaci phloem feeding duration 51. Therefore, the antifeedant property of imidacloprid and bifenthrin sublethal doses would give these insecticides potential to control insect pests indirectly, or at least to reduce their negative effects on the crops.

However, although this study showed that some biological traits of whiteflies are still affected even at low concentrations, the impact on other life history traits of this insect needs to be evaluated before deployment in this sense. Meanwhile, a long-term study should evaluate the potential sublethal effects on the broader insect community under field conditions, especially on natural enemies of B. tabaci. Sublethal effects can impair various key processes of the natural enemies' efficacy against pests 52-58. Studies on the effects of pesticides on natural enemies often aim at assessing the suitability of pesticides for Integrated Pest Management (IPM), therefore an appreciation of the lethal and sublethal effects on natural enemies as well would help to optimize IPM programmes involving use of both natural enemies and pesticides against pests like whiteflies in cotton 18,59.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by financial assistance from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2013CB127600) and Fujian Science and Technology Agency of China (2008J0062).

References

- 1.Oliveira M, Henneberry T, Anderson P. History, current status, and collaborative research projects for Bemisia tabaci. Crop Prot. 2001;20:709–723. [Google Scholar]

- 2.González-Zamora J, Moreno R. Model selection and averaging in the estimation of population parameters of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) from stage frequency data in sweet pepper plants. J Pest Sci. 2011;84:165–177. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Barro PJ, Liu SS, Boykin LM. et al. Bemisia tabaci: a statement of species status. Ann Rev Entomol. 2011;56:1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.do Valle GE, Lourenc AL, Pinheiro JB. Adult attractiveness and oviposition preference of Bemisia tabaci biotype B in soybean genotypes with different trichome density. J Pest Sci. 2012;85:431–442. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiao X, Xie W, Wang S. et al. Host preference and nymph performance of B and Q putative species of Bemisia tabaci on three host plants. J Pest Sci. 2012;85:423–430. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren SX, Wang ZX, Qiu BL. et al. The pest status of Bemisia tabaci in China and non-chemical control strategies. Entomol Sinica. 2001;8:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu BL, Dang F, Li SJ. et al. Comparison of biological parameters between the invasive B biotype and a new defined Cv biotype of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyradidae) in China. J Pest Sci. 2011;84:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang P, Tian YA, Biondi A. et al. Short-term and transgenerational effects of the neonicotinoid nitenpyram on susceptibility to insecticides in two whitefly species. Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:889–1898. doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0922-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He YX, Weng QY, Huang J. et al. Insecticide resistance of Bemisia tabaci field populations. Chin J Appl Ecol. 2007;18:1578–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad M, Arif M, Naveed M. Dynamics of resistance to organophosphate and carbamate insecticides in the cotton whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) from Pakistan. J Pest Sci. 2010;83:409–420. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng Y, Zhao JW, He YX. et al. Development of insecticide resistance and its effect factors in field population of Bemisia tabaci in Fujian Province, East China. Chin J Appl Ecol. 2012;23:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desneux N, Fauvergue X, Dechaume-Moncharmont FX. et al. Diaeretiella rapae limits Myzus persicae populations after applications of deltamethrin in oilseed rape. J Econ Entomol. 2005;98:9–17. doi: 10.1093/jee/98.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biondi A, Desneux N, Siscaro G. et al. Using organic-certified rather than synthetic pesticides may not be safer for biological control agents: Selectivity and side effects of 14 pesticides on the predator Orius laevigatus. Chemosphere. 2012;87:803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanaclocha P, Vidal-Quist C, Oheix S, Acute toxicity in laboratory tests of fresh and aged residues of pesticides used in citrus on the parasitoid Aphytis melinus. J Pest Sci. 2012. DOI:10.1007/s10340-012-0448-8.

- 15.Laurent FM, Rathahao E. Distribution of [14C] imidacloprid in sunflowers (Helianthus annuus L.) following seed treatment. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:8005–8010. doi: 10.1021/jf034310n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonmatin JM, Marchand PA, Charvet R. et al. Quantification of imidacloprid uptake in maize crops. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5336–5341. doi: 10.1021/jf0479362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang LP, Greenberg SM, Zhang YM. et al. Effectiveness of thiamethoxam and imidacloprid seed treatments against Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) on cotton. Pest Manag Sci. 2011;67:226–232. doi: 10.1002/ps.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desneux N, Decourtye A, Delpuech JM. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Ann Rev Entomol. 2007;52:81–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han P, Niu CY, Lei CL. et al. Quantification of toxins in a Cry1Ac+ CpTI cotton cultivar and its potential effects on the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:1452–1459. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0530-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han P, Niu CY, Lei CL. et al. Use of an innovative T-tube maze assay and the proboscis extension response assay to assess sublethal effects of GM products and pesticides on learning capacity of the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:1612–1619. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0546-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zappalà L, Siscaro G, Biondi A. et al. Efficacy of sulphur on Tuta absoluta and its side effects on the predator Nesidiocoris tenuis. J Appl Entomol. 2012;136:401–409. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wennergren U, Stark J. Modeling long-term effects of pesticides on populations: beyond just counting dead animals. Ecol Appl. 2000;10:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stark JD, Banks JE, Vargas R. How risky is risk assessment: The role that life history strategies play in susceptibility of species to stress. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:732–736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304903101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biondi A, Mommaerts V, Smagghe G. et al. The non-target impact of spinosyns on beneficial arthropods. Pest Manag Sci. 2012;68:1523–1536. doi: 10.1002/ps.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan Y, Biondi A, Desneux N. et al. Assessment of physiological sublethal effects of imidacloprid on the mirid bug Apolygus lucorum (Meyer-Dür) Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:1989–1997. doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0933-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLean DL, Kinsey MG. A Technique for electronically recording aphid feeding and salivation. Nature. 1964;202:1358–1359. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nauen R. Behaviour modifying effects of low systemic concentrations of imidacloprid on Myzus persicae with special reference to an antifeeding response. Pestic Sci. 1995;44:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao QG, Luo C, Guo XJ. et al. EPG-recorded probing and feeding behaviors of Bemisia tabaci and Trialeurodes vaporariorum on cabbage. Chin Bull Entomol. 2006;43:802–805. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniels M, Bale J, Newbury H. et al. A sublethal dose of thiamethoxam causes a reduction in xylem feeding by the bird cherry-oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi), which is associated with dehydration and reduced performance. J Insect Physiol. 2009;55:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui L, Sun LN, Shao XS. et al. Systemic action of novel neonicotinoid insecticide IPP-10 and its effect on the feeding behaviour of Rhopalosiphum padi on wheat. Pest Manag Sci. 2010;66:779–785. doi: 10.1002/ps.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollard DG. Feeding habits of the cotton whitefly, Bemisia tabaci Genn. (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) Ann Appl Biol. 1955;43:664–671. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alon M, Benting J, Lueke B, et al.Multiple origins of pyrethroid resistance in sympatric biotypes of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera. Aleyrodidae) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He YX, Zhao JW, Wu DD. et al. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid on Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) under laboratory conditions. J Econ Entomol. 2011;104:833–838. doi: 10.1603/ec10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao JW, He YX, Weng QY. et al. Effects of host plants on selection behavior and biological parameters of Bemisia tabaci Gennadius biotype B. Chin J Appl Ecol. 2009;20:2249–2254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson DD, Walker GP. Intracellular punctures by the adult whitefly Bemisia argentifolii on DC and AC electronic feeding monitors. Entomol Exp Appl. 1999;92:257–270. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yue M, Luo C, Xu H. Gluing techniques of gold wire electrode to Bemisia tabaci in electrical penetration graph. Chin Bull Entomol. 2005;42:326–328. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu BM, Yan FM, Chu D. et al. Difference in feeding behaviors of two invasive whiteflies on host plants with different suitability: implication for competitive displacement. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:697–706. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finney D. Probit analysis. London, UK: Cambridge University; 1971. p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- 39.SAS. SAS/STAT user's guide, Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calabrese EJ, Blain R. The occurrence of hormetic dose responses in the toxicological literature, the hormesis database: an overview. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2005;202:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devine GJ, Harling ZK, Scarr AW. et al. Lethal and sublethal effects of imidacloprid on nicotine-telerant Myzus incotianae and Myzus persicae. Pestic Sci. 1996;48:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widiarta IN, Matsumura M, Suzuki Y. et al. Effects of sublethal doses of imidacloprid on the fecundity of green leafhoppers, Nephotettix spp.(Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) and their natural enemies. Appl Entomol Zool. 2001;36:501–507. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bao HB, Liu SH, Gu JH. et al. Sublethal effects of four insecticides on the reproduction and wing formation of brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:170–174. doi: 10.1002/ps.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iftner DC, Hall FR, Sturm MM. Effects of residues of fenvalerate and permethrin on the feeding behaviour of Tetranychus urticae (Koch) Pestic Sci. 1986;17:242–248. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kontsedalov S, Weintraub P, Horowitz A. et al. Effects of insecticides on immature and adult western flower thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Israel. J Econ Entomol. 1998;91:1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boina DR, Onagbola EO, Salyani M. et al. Antifeedant and sublethal effects of imidacloprid on Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:870–877. doi: 10.1002/ps.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nauen R, Koob B, Elbert A. Antifeedant effects of sublethal dosages of imidacloprid on Bemisia tabaci. Entomol Exp Appl. 1998;88:287–293. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufmann L, Schürmann F, Yiallouros M. et al. The serotonergic system is involved in feeding inhibition by pymetrozine. Comparative studies on a locust (Locusta migratoria) and an aphid (Myzus persicae) Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2004;138:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo LE, van Loon JJA, Schoonhoven L. Behavioural and sensory responses to some neem compounds by Pieris brassicae larvae. Physiol Entomol. 1995;20:134–140. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu JC, Xu JX, Yuan SZ. et al. Pesticide-induced susceptibility of rice to brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Entomol Exp Appl. 2001;100:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang YX, Blas C, Barrios L. et al. Correlation between whitefly (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) feeding behavior and transmission of tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2000;93:573–579. [Google Scholar]

- 52.He YX, Zhao JW, Zheng Y. et al. Lethal effect of imidacloprid on the coccinellid predator Serangium japonicum and sublethal effects on predator voracity and on functional response to the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:1291–1300. doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnó J, Gabarra R. Side effects of selected insecticides on the Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) predators Macrolophus pygmaeus and Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae) J Pest Sci. 2011;84:513–520. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desneux N, Rafalimanana H, Kaiser L. Dose-response relationship in lethal and behavioural effects of different insecticides on the parasitic wasp Aphidius ervi. Chemosphere. 2004;54:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desneux N, Ramirez-Romero R, Kaiser L. Multistep bioassay to predict recolonization potential of emerging parasitoids after a pesticide treatment. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25:2675–2682. doi: 10.1897/05-562r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cordeiro EMG, Corrêa AS, Venzon M. et al. Insecticide survival and behavioral avoidance in the lacewings Chrysoperla externa and Ceraeochrysa cubana. Chemosphere. 2010;81:1352–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cabral S, Soares A, Garcia P. Voracity of Coccinella undecimpunctata: effects of insecticides when foraging in a prey/plant system. J Pest Sci. 2011;84:373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stara J, Ourednickova J, Kocourek F. Laboratory evaluation of the side effects of insecticides on Aphidius colemani (Hymenoptera: Aphidiidae), Aphidoletes aphidimyza (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), and Neoseiulus cucumeris (Acari: Phytoseidae) J Pest Sci. 2011;84:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Y, Wu K, Jiang Y. et al. Widespread adoption of Bt cotton and insecticide decrease promotes biocontrol services. Nature. 2012;487:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature11153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]