Abstract

Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma is an uncommon benign tumor of the jaws that belongs to the group of mixed odontogenic tumors. The descriptions of its clinical and radiological features in the literature are not always accurate and sometimes even contradictory. The aim of the present study was to critically evaluate their clinical and radiological features as reported in the English-language literature. A total of 114 well–documented cases of ameloblastic fibro-odontomas (103 from publications and 11 of our own new cases) were analyzed. The patients’ age ranged from 8 months to 26 years (mean 9.6). There were 74 (65 %) males, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.85:1 (P = 0.001). The mandible was involved in 74 (65 %) cases, and the mandible-to-maxilla ratio was 1.85:1 (P < 0.001). Nearly 80 % of the lesions were located in the posterior region of the jaws, and most (58 %) were in the posterior mandible. Radiographically, most of the lesions were unilocular and only a few (~10 %) were multilocular. Most lesions were mixed radiolucent-radiopaque, and only a few (~5 %) were radiolucent. Almost all lesions (~92 %) were associated with the crown of an unerupted tooth/teeth. This comprehensive analysis of a large number of patients with an uncommon lesion revealed that ameloblastic fibro-odontomas are significantly more common in males and in the mandible, and that multilocular lesions are uncommon. It also revealed that, based on their clinical and radiological features, some of them are probably true neoplasms while others appear to be developing odontomas (hamartomas).

Keywords: Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma, Mixed odontogenic tumors, Ameloblastic fibroma, Developing odontoma, Odontoma

Introduction

Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma (AFO) has been defined by the WHO as a rare odontogenic tumor with the histopathological features of an ameloblastic fibroma (AF) in conjunction with the presence of dentin and enamel [1]. Histopathologically, the tumor is composed of soft and hard tissues. The soft tissue component is composed of epithelial strands and small islands of odontogenic epithelium associated with a primitive–appearing myxoid connective tissue that resembles the dental papilla. The hard tissue component consists of foci of enamel and dentin [2]. According to the scant information on AFO that is provided in the 2005 WHO classification of odontogenic tumors [1], AFO is a “tumor of children with a mean age between 8 and 12 years with no gender or anatomic site predilection. Radiologically, it exhibits a well-circumscribed, unilocular or multilocular radiolucency with varying levels of radiopacity”. The findings of the present study, which is based on a comprehensive analysis of the literature, add new information on the demographic, clinical and radiographic characteristics of AFO.

AFOs had originally been termed ameloblastic odontomas but in 1971 the WHO suggested that this term is inappropriate since it encompasses two types of odontogenic tumors that share a different histology and biologic behavior [3]. They suggested that tumors presenting a histopathological combination of AF and a complex odontoma and that is biologically non-invasive be termed AFOs, and those that histopathologically represent a combination of ameloblastoma and complex odontoma and behave in an invasive manner, like the classical ameloblastoma, be termed odontoameloblastoma.

An AFO is a rare tumor and its relative frequency within the group of odontogenic tumors seen in oral pathology biopsy services in various parts of the world reportedly ranges from 0 to 3.4 % [4]. Because of its rarity, there are sparse details in the literature regarding its clinical and radiological features, and some of the existing reports are conflicting. Except for two comprehensive reviews that were published about 30 and 15 years ago [5, 6] most of the papers on AFOs describe single cases and a few report on small series of cases.

The purpose of the present investigation was to critically analyze the clinical and radiological features of AFOs based on case reports and case series published in the literature, and to add 11 cases from our own files, in order to update and improve our knowledge and diagnostic ability of this entity.

Methods

The English-language literature was searched for adequately documented cases of AFOs published between 1967 and 2010. Medline’s PubMed and Google Scholar were searched using the keywords “ameloblastic fibro-odontoma” and “ameloblastic odontoma”. References of published papers were also searched for additional cases. Included in the study were only cases that exhibited the histopathological features of AFO, namely the presence of dental papilla-like tissue with epithelial strands and nests, as seen in AF, and induction changes with the formation of dentin and enamel. Additional inclusion criteria were information of the clinical features and an acceptable radiographic image or detailed radiological description for each case. Not all data were available for all cases. Special attention was given to cases that were diagnosed in the past as ameloblastic odontoma since this term was used historically for both ameloblastic fibro-odontoma and odontoameloblastoma [3]. The cases of ameloblastic odontoma in which the histopathology was consistent with odontoameloblastoma were excluded from the study, as were cases that were published under the title of AFO but the histopathology was consistent with ameloblastic fibrodentinoma or odontoma.

We also omitted from our study cases that were diagnosed as ameloblastic fibrodentinoma (AFD) because of the ongoing debate as to whether AFD is a variant of ameloblastic fibroma, a variant of AFO, or a separate entity altogether. In the 1971 WHO classification [3], AFD was considered to be a separate entity. In the 1992 WHO classification [2], it was considered to be a variant of AFO, and in the latest 2005 WHO classification [1], it was considered to be a variant of ameloblastic fibroma. On the other hand, Reichart and Philipsen [7] and Praetorious [8] have recently suggested that AFD should be considered a separate entity and did not include AFD in their analysis of AFOs. Because of the continuous debate and the lack of agreement among oral pathologists, we decided not to include AFD in our current analysis. Finally, the series of cases by Buchner et al. [4] and Hooker [9] were excluded because there was no individual clinical and radiological information.

A total of 114 cases (103 from publications and 11 new cases from our files) were analyzed [10–84]. The data of 11 new cases are described in Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2, and they represent the largest detailed series of cases from one biopsy service to have been thus far reported.

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological features of 11 new cases of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma

| Case # | Age (years) | Gender | Jaw | Area | Expansion | Size (cm) | Locularity | Content | Border | Unerupted tooth | Displaced tooth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | F | Max | Molars and sinus | Yes | 2.5 | Uni | Rl with scattered opacities | Mostly defineda | 16 | Superior |

| 2 | 12 | M | Max | Incisors | Yes | 1.0 | Uni | Rl with small central opacity | Well defined | Nob | Distal |

| 3 | 13 | M | Mand | Molar and ramus | Yes | 5.0 | Uni | Rl with large number of opacities | Well defined | 47 | Inferior |

| 4 | 3 | M | Max | Incisor | No | 1.1 | Uni | Rl with few opacities | Well defined | 51 | Superior |

| 5 | 8 | F | Mand | Molars | No | 1.5 | Uni | Rl with small opacity | Well defined | 46 | Inferior |

| 6 | 3 | M | Mand | Cuspid | Yes | 0.8 | Uni | Rl with dense mass | Well defined | 83 | No |

| 7 | 10 | M | Mand | Molars | Yes | 3.0 | Uni | Rl with few opacities | Well defined | 46c | Inferior |

| 8 | 13 | M | Mand | Molars | Minimal | 1.5 | Uni | Rl with few opacities | Mostly defineda | 47d | Inferior |

| 9 | 9.5 | M | Max | Molars and sinus | No | 3.0 | Uni | Rl with opacities | Well defined | 25–27 | 25–26 superior, 27 posterior |

| 10 | 8.5 | F | Mand | Premolars and molars | Yes | 1.5 | Multi | Rl with few small opacities | Well defined | 35 | Inferior |

| 11 | 9 | M | Mand | Premolar and molar | Yes | 4.0 | Multi | Rl with few small opacities | Well defined | 44–46 | Inferior |

M male, F female, Max maxilla, Mand mandible, Uni unilocular, Multi multilocular, Rl radiolucency

aMostly but not entirely defined

bBetween roots of erupted teeth 11,12; c Missing tooth 47; d Missing tooth 48

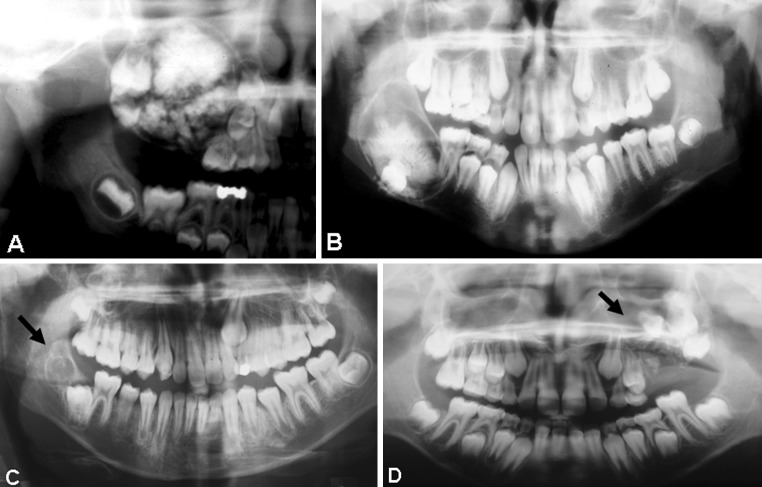

Fig. 1.

Radiographs showing ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. a Case 1. b Case 3. c Case 8. d Case 9

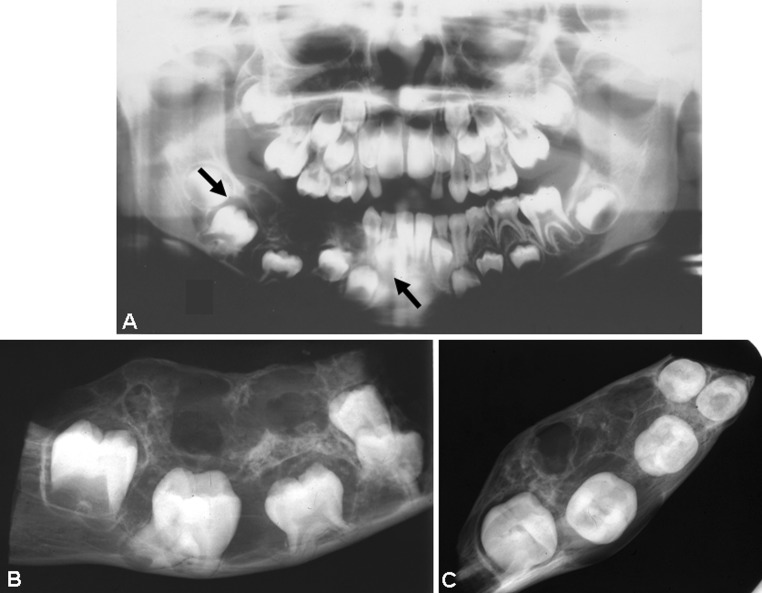

Fig. 2.

a Panoramic radiograph of Case 11 showing a multilocular radiolucency with few small opacities. b and c Radiographs of the resected specimen of the mandible

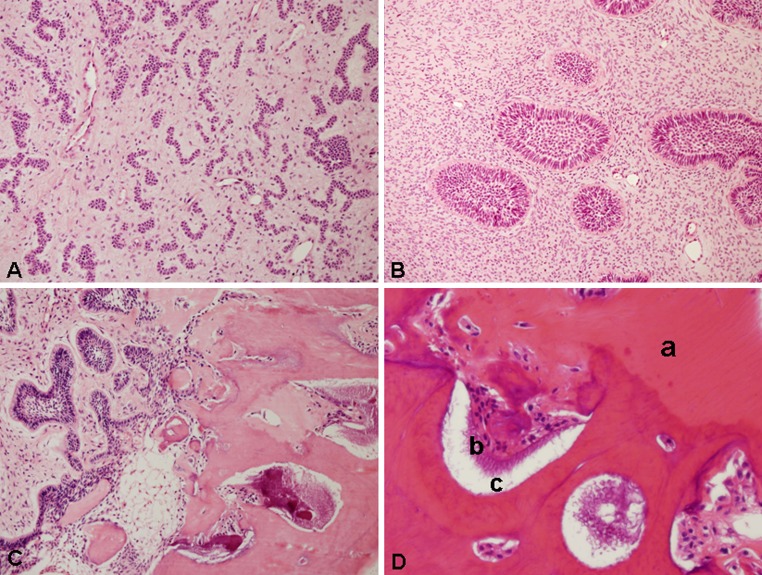

The histopathologic features of our 11 cases were basically similar. The lesions were composed of a soft tissue component and calcified elements. The soft tissue resembled ameloblastic fibroma and exhibited mainly strands and cords of odontogenic epithelium that resembled the dental lamina (Fig. 3a). In a few cases, the lesion also contained epithelial islands that consisted of a peripheral layer of columnar palisaded cells, which enclosed loosely arranged cells resembling the enamel organ of a developing tooth (Fig. 3b). The epithelial elements were supported by loose primitive connective tissue containing randomly oriented fibroblasts that resembled the dental papilla of a developing tooth. Mesenchymal tissue dominated in some lesions, while there was an abundance of epithelial elements in others. The calcified elements showed the characteristic structure of an odontoma consisting of irregular dentin, an enamel matrix and enamel in close relationship to the epithelial elements (Fig. 3c). The dentin contained entrapped epithelial and mesenchymal cells. The dentinal structures enclosed clefts or hollow spaces that contained mature enamel that was removed during decalcification. The spaces also contained areas of enamel matrix (Fig. 3d). The soft tissue component dominated in some lesions, while hard tissue was abundant in others.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. a Strands, cords and nests of odontogenic epithelium supported by richly cellular connective tissue (HE, original magnification ×200). b Epithelial islands showing a peripheral, tall columnar palisaded layer enclosing stellate reticulum-type cells in a primitive-appearing myxoid connective tissue (HE, original magnification ×200). c Intermediate zone between the soft tissue component and the hard tissue composed of dentin and enamel (HE, original magnification ×200). d Higher magnification of the hard tissue component composed of dentin (a), enamel matrix (b) and enamel spaces (c) (HE, original magnification ×400)

All the cases were treated by enucleation and curettage, except for case 11 that was treated by segmental resection. Follow-up of the 11 lesions ranged from 5 to 20 years and none had a recurrence.

The clinical and radiological data of the 114 lesions were evaluated according to the criteria proposed by White [85], which include age, gender, location, symptoms, expansion and radiological features of lesion size, content, borders, loculation, tooth relation, tooth impaction, tooth displacement and root resorption. The size was determined according to the greatest dimension. In the present study, incisors and canines were regarded as composing the anterior region. Premolars (or primary molars), molars and ramus (in the mandible) and molars and sinus (in the maxilla) were regarded as composing the posterior region.

Differences in the frequency of the lesions between genders, jaw location (mandible or maxilla) and lesion size (in the mandible versus in the maxilla) were analyzed by the Chi-square test and crosstabs test using the SPSS software (Chicago, IL, USA). Significance was set at P < 0.05.

The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Tel Aviv University.

Results

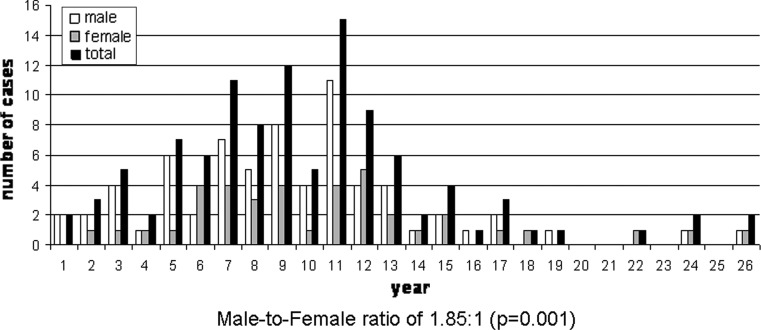

A total of 114 cases of AFO were analyzed, of which 11 were new and are now being reported for the first time. Data on the age and gender distribution of AFOs were known in all 114 cases and they are shown in Fig. 4. At the time of initial presentation, the patient’s age ranged from 8 months to 26 years (mean 9.6, median 9.0). Most of the cases (71 %) were diagnosed in patients between 5 and 14 years of age, and only 4.3 % cases were diagnosed in patients older than 20 years. There were 74 (65 %) males and 40 (35 %) females, with a male–to–female ratio of 1.85:1 (P = 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Age and gender distribution of ameloblastic fibro-odontomas at the time of presentation (n = 114)

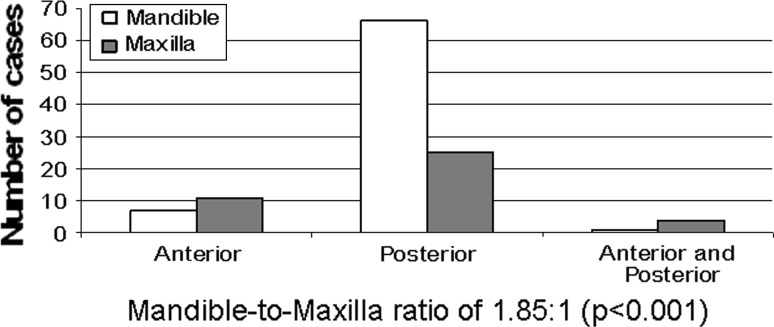

The distribution of the lesion (mandible or maxilla) was known for all cases. Lesions were located in the mandible in 74 (65 %) cases and in the maxilla in 40 (35 %), with a mandible–to–maxilla ratio of 1.85:1 (P < 0.001). Figure 5 shows the specific location within the mandible and maxilla. Nearly 80 % of the lesions were located in the posterior region of the jaws and only 15.8 % in the anterior region, while 4.4 % of the lesions were located in both regions. In patients 7 years and older, the posterior mandible was the most frequently involved region compared to the anterior region of the mandible and anterior and posterior regions of the maxilla (P < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of ameloblastic fibro-odontomas in the mandible and maxilla (n = 114)

The clinical presentation of the AFOs was reported in 94 cases. An AFO is characteristically painless and slow growing, and usually expands with time. In 27 (29 %) cases, the lesion was asymptomatic and discovered on radiographs taken because of failure of tooth eruption or during preparation for orthodontic treatment. There was a painless expansion of bone in 44 (47 %) cases and facial asymmetry, sometimes very pronounced, due to severe expansion of bone in 23 (24 %) cases. Only two patients complained of pain [18, 65].

Data on radiographic characteristics of AFOs are shown in Table 2. AFOs usually manifested as unilocular lesions (90.3 %), and multilocular lesions were uncommon (9.7 %). Most of the lesions were described as being mixed radiolucent-radiopaque (94.8 %) and only a few were radiolucent (5.2 %). In the latter lesions, the amount of the calcified material was so small that it was not visible on radiographs. Mixed lesions exhibited several patterns, such as radiolucency with a few scattered opacities, radiolucency with a large number of opacities in various size and shapes, and a single opaque mass (usually in the center) that was surrounded by a narrow or wide area of radiolucency. The borders of the lesion were well–defined in almost all cases (91 %), and only a few lesions were mostly but not entirely defined and locally non-defined (9 %).

Table 2.

Radiological features of ameloblastic fibro-odontomas

| Locularity (n = 93) | |

| Unilocular | 84 (90.3 %) |

| Multilocular | 9 (9.7 %) |

| Density (n = 97) | |

| Radiolucent | 5 (5.2 %) |

| Radiolucent and radiopaque (mixed) | 92 (94.8 %) |

| Few scattered opacities | 33 |

| Large number of opacities | 8 |

| Single opaque mass | 19 |

| Mixed, WS | 32 |

| Border (n = 89) | |

| Well–defined | 81 (91 %) |

| Mostly defined and locally not defined | 8 (9 %) |

| Tooth relationship (n = 95) | |

| Associated with crown of unerupted tooth | 87 (91.6 %) |

| Not associated with unerupted tooth | 8 (8.4 %) |

WS without specification

The tooth relationship with the lesion was known for 95 cases. Most of the lesions (n = 87, 91.6 %) were associated with a single unerupted tooth or with several unerupted teeth, usually of the permanent dentition but also of the primary dentition. The lesion was usually located coronally to the crown of the tooth/teeth. Table 3 shows the specific unerupted teeth that are associated with the lesion. Sixty-three cases were associated with one unerupted tooth and 24 cases with several (i.e., 2–5) unerupted teeth. The first and second permanent molars were the most common teeth to be associated with an AFO. The unerupted teeth were usually displaced inferiorly in the mandible and superiorly in the maxilla. In a very few cases, the AFOs had developed between roots of erupted teeth, in the periapical area of erupted teeth, or in place of a tooth [10, 56, 61, 63, 65, 84], Cases 2, 7, and 8 of the present study]. Root resorption caused by AFO was rare, having been reported in only three cases [33, 56, 74]. Perforation of the cortical plates is also uncommon, having been reported in only six cases [23, 30, 43, 45, 71, 75].

Table 3.

Unerupted teeth associated with ameloblastic fibro-odontomas (n = 87)

| Mandible | Maxilla | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent | Primary | Permanent | Primary | ||||

| Tooth # | No. of cases | Tooth # | No. of cases | Tooth # | No. of cases | Tooth # | No. of cases |

| Single tooth | Single tooth | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | – | 2 | – | 2 | – | 2 | – |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | – |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | – | 4 | – | 4 | – |

| 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | – | 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 16 | 6 | 9 | ||||

| 7 | 15 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| 8 | 5 | 8 | 1 | ||||

| Total | Total | ||||||

| 40 | 5 | 16 | 2 | ||||

| Multiple teeth | Multiple teeth | ||||||

| 3–5 | 1 | 2–3 | 1 | 2–6 | 1 | 1–2 | 1 |

| 4–6 | 1 | 4–5 | 1 | 4–7 | 1 | 1–3 | 1 |

| 4–7 | 2 | 5–7 | 2 | ||||

| 5–6 | 3 | 6–7 | 3 | ||||

| 5–7 | 1 | 7–8 | 1 | ||||

| 6–7 | 3 | ||||||

| 6–8 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | Total | ||||||

| 12 | 2 | 8 | 2 | ||||

The size of the AFO was known in 93 cases. Lesion size ranged from 0.8 to 14 cm (mean 3.3 cm, median 3.0 cm). Although the mean size of the mandibular lesions was 3.1 cm and that of the maxilla 3.6 cm, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Also, there was no association between the size of the lesions and the age of the patients (P > 0.05). It is worthy to note that the sizes of AFOs are relatively large considering the fact that they develop in the small jaws of children.

Discussion

An AFO belongs to the group of mixed odontogenic tumors that histopathologically represent odontogenic epithelium with odontogenic ectomesenchyme, with or without hard tissue formation [2]. In general, this group of lesions is composed of AFs, ameloblastic fibro-dentinomas and AFOs. There is ongoing debate and disagreement among oral pathologists as to the relation of these lesions to the complex odontoma lesion. Some believe in the “maturation theory”, which suggests that an AF will develop through a continuum of differentiation and maturation into an AFO and eventually to a complex odontoma, which is a hamartoma [86]. Other authors claim that while an AF is probably a true neoplasm, an AFO should be regarded as an immature complex odontoma, thereby indicating that AFO is a hamartoma [5, 6]. On the other hand, there are oral pathologists who believe that AFs and AFOs are separate and distinct pathological entities that represent a neoplasm [1, 2, 8, 87]. They claim that an AFO differs significantly from the hamartomatous odontoma by having a greater potential for growth and causing considerable deformity and bone destruction [88, 89]. Furthermore, there is a malignant counterpart for AFO, the ameloblastic fibro-odontosarcoma [90, 91]. Trodahl [92] suggested that the truth may lie somewhere between these two poles of opinion. He pointed out that odontomas must have gone through a development stage and that a non-calcified stage of development must have occurred. This stage would mimic the histopathological appearance of an AF. As such, he concluded that there are two lesions that have the same histopathological appearance of an AF: one is the early stage of a developing odontoma and the other is the actual neoplasm. According to Gardner [93], the same also holds true for an AFO, i.e., some lesions with the histopathological appearance of an AFO are probably developing odontomas and some are the actual neoplasms. The problem is that the histopathological appearance of AFO in its neoplastic form is indistinguishable from a developing odontoma, whereupon clinical and radiological features may be of assistance in making the distinction. There is no question that large, expansile lesions that exhibit extensive bone destruction, cortical perforation and loosening of teeth are neoplasms. Some typical example are huge maxillary tumors, like the one reported by Miller et al. [18 Case 4], in which the extensive maxillary enlargement caused disfigurement and interfered with nasal respiration, feeding and speech, as well as the maxillary aggressive tumor reported by Piette et al. [40] that caused destruction of the maxillary sinus and extended to the orbital floor and pterygoid region. Other examples are the massive aggressive tumor of the maxilla reported by Hegde and Hemavathy [75] that caused facial disfigurement, perforated the buccal plate and presented as a soft tissue mass, and the case described by Ozer et al. [47] in which the tumor occupied the maxillary sinus with expansion of its walls causing proptosis. There are several other reports of large aggressive maxillary tumors in the literature [29, 54, 67, 68, 74]. Examples of large destructive mandibular lesions where the tumor extended from the premolar or molar area to the sigmoid notch, coronoid notch or neck of the condyle were reported by several authors [17, 19, 46, 50]. On the other hand, asymptomatic small lesions directly overlying the crown of an unerupted tooth in young subjects, with no or minimal expansion of bone, are likely to be developing odontomas (immature odontomas) rather than neoplasms [2, 54, 93]. Examples of these are probably the cases reported by Olech and Alvares [10], Miller et al. [18, Case 3], and Warnock et al. [38].

In light of these collected data, we can assume that some cases that have been reported in the literature under the diagnosis of AFO are, in fact, examples of developing odontoma. However, at the present time, there is no unequivocal way of distinguishing between a neoplastic AFO and a developing odontoma [7, 8, 37, 89, 93].

The clinical and radiological profiles of AFOs that are described in many papers and textbooks of oral pathology are not always accurate because the authors rely on data from small series of cases. There is no argument in the literature that an AFO is an uncommon lesion of children and adolescence. In our current study, the mean age of the patient was 9.6 years, in the review by Philipsen et al. [6] it was 9.0 years, and in the 2005 WHO classification of odontogenic tumors it was between 8 and 12 years [1]. There is, however, disagreement between our findings on gender differences and some of those reported in the literature. In the 2005 WHO classification [1] as well as in the textbook of Neville et al. [89], it is claimed that there is no gender predilection. Our study revealed that the AFO is significantly more common in males (F:M = 1:1.85, P = 0.001). There is also disagreement between our study results and some of those in the literature regarding the site of an AFO lesion. Some authors claim that there is slight predilection for the maxilla [94], others claim that AFO is evenly divided between the mandible and maxilla. The 2005 WHO classification [1] also states that there is no site predilection. Our findings revealed that an AFO is more common in the mandible (maxilla–to–mandible ratio of 1:1.85) and that the difference is of statistical significance (P < 0.001).

As for the radiological features of an AFO, most authors state that it presents as a “unilocular or multilocular lesion” [1, 7, 95]. Although this statement generally holds true, our study revealed that about 90 % of the lesions are unilocular and that 10 % are multilocular. Thus, it would be more correct to state that an AFO is usually a unilocular lesion and that multilocular lesions are uncommon.

The treatment of an AFO, which in most cases is a well-defined, circumscribed, non-aggressive, noninvasive lesion, is by conservative surgical enucleation [7]. However, the larger, more extensive and destructive lesions may require surgical resection of either partial maxillectomy [40, 68] or partial mandibulectomy [33, 66, and Case 11 of the present study].

Recurrence of AFO is uncommon and our search yielded only 4 cases [50, 57, 66]. The histopathology of the recurrent lesions was AFO in two cases [50, 57] and complex odontoma in the other two [66]. The latter two cases may lend support to the theory that some AFOs are indeed immature odontomas. Some authors suggest that recurrence occurs due to a residual lesion resulting from inadequate surgical removal at the time of initial treatment [66], but others refute that possibility [57].

Only a small number of AFOs have been submitted to molecular and genetic studies but no significant findings have been found thus far that can contribute to our knowledge of the biological behavior of this lesion [96, 97].

It is important not to confuse AFOs with odontoameloblastomas that are extremely rare tumors and that, like AFOs, occur in young age groups. Odontoameloblastomas consist histopathologically of a combination of ameloblastomas and odontomas. The odontogenic epithelium proliferates in a follicular or plexiform pattern in a mature connective tissue stroma, like a conventional ameloblastoma. Intermingled with this tissue are dental hard structures similar to a compound or a complex odontoma. Unlike AFOs, odontoameloblastomas have an aggressive biological behavior such as that seen in conventional ameloblastomas and they are treated in the same manner [98].

In summary, an AFO is an uncommon lesion that belongs to the group of mixed odontogenic tumors. There is ongoing debate in the literature as to whether it should be regarded as a true neoplasm or as a developing odontoma (hamartoma). The problem is that both lesions share the same histopathological appearance. Our analysis of the literature revealed that some lesions that exhibit aggressive growth, causing considerable facial deformity and bone destruction, probably represent true neoplasms, while others that are small, asymptomatic and have no bony expansion probably represent developing odontomas (hamartomas). Since the literature relies on single case reports and small series of cases, there are many inaccuracies and conflicting data on the lesion’s clinical and radiographic features. Our current analysis revealed that an AFO is not equal between genders but rather significantly more common in males, that it is not equally distributed between the mandible and the maxilla but significantly more common in the mandible, and that it does not present as a unilocular or multilocular lesion but mostly unilocular and that multilocular AFO lesions are uncommon.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Ed and Herb Stein Chair in Oral Pathology, Tel Aviv University. The authors would like to thank Prof. S. Calderon and Prof. S. Taicher for the radiographs of cases number 3 and 11, and to Ms. Esther Eshkol for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Takeda Y, Tomich CE. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramer IRH, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. Histological Typing of Odontogenic Tumours. 2. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pindborg JJ, Kramer IRH. Histological Typing of Odontogenic Tumours, Jaws Cysts, and Allied Lesions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of central odontogenic tumors: a study of 1,088 cases from Northern California and comparison to studies from other parts of the world. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1343–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slootweg PJ. An analysis of the interrelationship of the mixed odontogenic tumors: ameloblastic fibroma, ameloblastic fibro-odontoma and odontoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;51:266–276. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Praetorius F. Mixed odontogenic tumours and odontomas. Consideration on interrelationship. Review of the literature and presentation of 134 new cases of odontomas. Oral Oncol. 1997;33:86–89. doi: 10.1016/S0964-1955(96)00067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. Odontogenic Tumors and Allied Lesions. London: Quintessence; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Praetorius F. Odontogenic Tumors. In: Barnes L. Surgical pathology of the head and neck. 3rd ed. India: Informa; 2009.

- 9.Hooker SP. Ameloblastic odontoma: an analysis of twenty-six cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;24:375–376. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olech E, Alvares O. Ameloblastic odontoma. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;23:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(67)90543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamner JE, Pizer ME. Ameloblastic odontoma: report of two cases. Am J Dis Child. 1968;115:332–336. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1968.02100010334006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobsohn PH, Quinn JH. Ameloblastic odontoma: reports of three cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;26:829–836. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutta A. Ameloblastic odontoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;29:827–831. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(70)90431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien FV. Ameloblastic odontome: a case report. Br Dent J. 1971;131:71–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4802702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worley RD, McKee PE. Ameloblastic odontoma: report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1972;30:764–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders DW, Kolodny SC, Jacoby JK. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1974;32:281–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meerkotter VA. The ameloblastic fribro-odontome: report of a case and the histogenesis of an anomalous denticle. J Dent Ass S Afr. 1974;29:389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller AS, Lopez CF, Pullon PA, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Report of seven cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41:354–365. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanna RJ, Regezi JA, Hayward JR. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of case with light and electron microscopic observations. J Oral Surg. 1976;34:820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cran JA, Herd JR, Chau KK. An unusual odontogenic lesion: case report. Aus Dent J. 1976;21:520–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1976.tb05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eda S, Tokuue S, Kato K, et al. A melanotic ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 1977;18:119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herd JR. An ameloblastic fibro-odontome. Aus Dent J. 1977;22:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1977.tb04433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Album MM, Neff JH, Myerson RC. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of a case. ASDC J Dent Child. 1977;44:320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geller LJ, Fielding AF. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a case report. J Dist Columbia Dent Soc. 1978; Spring:65–70. [PubMed]

- 25.Bernhoft CH, Bang G, Gilhuus-Moe O. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Int J Oral Surg. 1979;8:241–244. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(79)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slootweg PJ. Epithelio-mesenchymal morphology in ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a light and electron microscopic study. J Oral Pathol. 1980;9:29–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1980.tb01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josephsen K, Larsson A, Pejerskov O. Ultrastructural features of epithelial-mesenchymal interface in an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Scand J Dent Res. 1980;88:79–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1980.tb01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curran JB, Owen D, Lanoway J. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of a case. J Can Dent Assoc. 1980;46:314–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daley TD, Lovas GL. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of a case. J Can Dent Assoc. 1982;48:467–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutt PH. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of a case with documented four-year follow-up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982;40:45–48. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(82)80016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anneroth G, Modeer T, Twetman S. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma in the mandible. A case report. Int J Oral Surg. 1982;11:130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(82)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reilly JS, Supance JS. Pathologic quiz case 1: ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:200–203. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800170066020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reich RH, Reichart PA, Ostertag H. Ameloblastic fibro-odontome. Report of a case with ultrastructural study. J Maxillofac Surg. 1984;12:230–234. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(84)80250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sole MS, Jacobson SM, Edwab RR, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. N Y State Dent J. 1986;52:20–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawkins PL, Sadeghi EM. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:1014–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(86)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda Y, Suzuki A, Kuroda M, et al. Pigmented ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: detection of melanin pigment in enamel. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 1988;29:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen LS, Ficarra G. Mixed odontogenic tumors: an analysis of 23 new cases. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10:330–343. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warnock GR, Pankey G, Foss R. Well-circumscribed mixed-density lesion coronal to unerupted permanent tooth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119:311–312. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1989.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glickman R, Salman L, Chaudhry AP. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a case report. Ann Dent. 1989;48:25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piette EM, Tideman H, Wu PC. Massive maxillary ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: case repot with surgical management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:526–530. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90247-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cataldo E, Santis HR. A clinico-pathologic presentation: ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. J Mass Dent Soc. 1992;41(53):83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okura M, Nakahara H, Matsuya T. Treatment of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma without removal of the associated impacted permanent tooth: report of cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:1094–1097. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90498-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker WR, Swift JQ. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma of the anterior maxilla: report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:294–297. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitano M, Tsuda-Yamada S, Semba I, et al. Pigmented ameloblastic fibro-odontoma with melanophages. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyauchi M, Takata T, Ogawa I, et al. Immunohistochemical observations on a possible ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:93–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sekine J, Kitamura A, Ueno K, et al. Cell kinetics in mandibular ameloblastic fibro-odontoma evaluated by bromodeoxyuridine and proliferating cell nuclear antigen immunohistochemistry: case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34:450–453. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(96)90106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozer E, Pabuccuouglu U, Gunbay U, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma of the maxilla: case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1997;21:329–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Favia GF, Di Alberti L, Scarano A, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of two cases. Oral Oncol. 1997;33:444–446. doi: 10.1016/S0964-1955(97)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savitha K, Cariappa KM. An effective extraoral approach to the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;27:61–62. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(98)80099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furst I, Pharoah M, Phillips J. Recurrence of an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma in a 9-year-old boy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:620–623. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haring JI. Case study. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. RDH. 1999;19(12):64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao NR. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of two cases. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1999;70:90–91. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinberg MJ, Herrera AF, Frontera Y. Mixed radiographic lesion in the anterior maxilla in a 6-year-old boy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:317–321. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flaitz CM, Hicks J. Delayed tooth eruption associated with an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:253–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.al-Sebaei MO, Gagari E. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. J Mass Dent Soc. 2001;50:52–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yagishita H, Taya Y, Kanri Y, et al. The secretion of amelogenins is associated with the induction of enamel and dentinoid in an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:499–503. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.030008499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fridrich RE, Siegert J, Donath K, et al. Recurrent ameloblastic fibro-odontoma in a 10-year-old boy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1362–1366. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.27537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fantasia JE, Damm DD. Mandibular radiolocency: ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Gen Dent. 2002;50(202):204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang H, Precious DS, Shimizu MS. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baughman R. Testing your diagnostic skills. Case no. 2. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Todays FDA. 2003;15(16):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alderson GL, McGuff HS, Jones AC, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology case of the month. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Tex Dent J. 2004;121(427):431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dhanuthai K, Kongin K. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004;29:75–77. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.29.1.f0543117u42n4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Gelderblom HR, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of two cases with ultrastructural study of tumour dental hard structures. Oral Oncol Extra. 2004;40:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2003.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sivapathasundharam B, Manikandhan R, Sivakumar G, et al. Amelobalstic fibro odontoma. Indian J Dent Res. 2005;16:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baughman R. Testing your diagnostic skills. Case no. 1. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Todays FDA. 2005;17(20):22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y, Li TJ, Gao Y, et al. Ameloblastic fibroma and related lesions: a clinicopathologic study with reference to their nature and interrelationship. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:588–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soares RC, Godoy GP, Neto JC, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: report of a case presenting an unusual clinical course. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2006;1:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pedex.2006.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu Y, Liu B, Su T, et al. A huge ameloblastic fibro-odontoma of the maxilla. Oral Oncol Extra. 2006;42:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2005.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Silva GCC, Jham BC, Silva EC, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Oral Oncol Extra. 2006;42:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2005.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oghli AA, Scuto I, Ziegler C, et al. A large ameloblastic fibro-odontoma of the right maxilla. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E34–E37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang JY, Marcantoni H, Kessler HP. Oral and maxillofacial pathology case of the month. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Tex Dent J. 2007;124(686–7):694–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gyulai-Gaal S, Takacs D, Szabo G, et al. Mixed odontogenic tumors in children and adolescents. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1338–1342. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e3180a7730f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reis SR, de Freitas CE, do Espirito Santo AR. Management of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma in a 6-year girl preserving the associated impacted permanent tooth. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:331–335. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dolanmaz D, Pampu AA, Kalayci A, et al. An unusual size of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:179–182. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/25869989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hegde V, Hemavathy S. A massive ameloblastic fibro-odontoma of the maxilla. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:162–164. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zouhary KJ, Said-Al-Naief N, Waite PD. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: expansile mixed radiolucent lesion in the posterior maxilla: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e15–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Atwan S, Geist JR. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: case report and review of the literature. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2008;90:46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anonymous. Oral pathology quiz #62. Case number 4. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. JN J Dent Assoc. 2009;80:19, 23. [PubMed]

- 79.Nascimento JE, Araujo LD, Almeida LY, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a conservative surgical approach. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:e654–e657. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cavalcante AS, Anbinder AL, Costa N, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:e650–e653. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Riu G, Meloni SM, Contini M, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Case report and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010;38:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhattacharyya I. Case of the month. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. Todays FDA. 2010;22:21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wewel J, Narayana N. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma of the anterior mandible in a 22-month-old boy. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:618–620. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.74237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Souza Tolentino E, Centurion BS, Lima MC, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dent. 2010;2010:pii104630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.White SC. Computer-aided differential diagnosis of oral radiopaque lesions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1989;18:53–59. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.18.2.2699592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cahn LR, Blum T. Ameloblastic odontoma: case report critically analyzed. J Oral Surg. 1952;10:169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cawson RA, Binnie WH, Speight P, et al. Lucas’s Pathology of Tumors of the Oral Tissues. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Howell RM, Burkes EJ., Jr Malignant transformation of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma to ameloblastic fibrosarcoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1997;43:399–401. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mainenti P, Oliveira GS, Valerio JB, et al. Ameloblastic fibro-odonotosarcoma: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trodahl JN. Ameloblastic fibroma: a survey of cases from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;33:547–558. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gardner DG. The mixed odontogenic tumors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58(166–8):93. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pindborg JJ, Hjorting-Hansen E. Atlas of Diseases of the Jaws. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Odell EW, Morgan PR. Biopsy Pathology of the Oral Tissues. London: Chapman and Hall Medical; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Galvao CF, Gomes CC, Diniz MG, et al. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in tumour suppressor genes in benign and malignant mixed odontogneic tumours. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:389–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Papagerakis P, Peuchmaur M, Hotton D, et al. Aberrant gene expression in epithelial cells of mixed odontogenic tumors. J Dent Res. 1999;78:20–30. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mosqueda-Taylor A, Carlos-Bregni R, Ramírez-Amador V, et al. Odontoameloblastoma. Clinico-pathologic study of three cases and critical review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:800–805. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]