Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins are key signaling molecules in response to cytokines and in regulating T cell biology. However, there are contradicting reports on whether STAT is involved in T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) signaling. To better define the role of STAT in TCR signaling, we activated the CD4/CD8-associated Lck kinase by co-crosslinking TCR and CD4/CD8 co-receptors in human peripheral blood T cells. Sequential STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 activation was observed 1 hour after TCR stimulation suggesting that STAT proteins are not the immediate targets in the TCR complex. We further identified interferon-gamma as the key cytokine in STAT1 activation upon TCR engagement. In contrast to transient STAT activation in cytokine response, this autocrine/paracrine-induced STAT activation was sustained. It correlated with the absence of two suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins, SOCS3 and cytokine-inducible SH2 containing protein, that are negative feedback regulators of STAT signaling. Moreover, enforced expression of SOCS3 inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation of zeta-associated protein kinase of 70 kD in TCR-stimulated human Jurkat T cells. This is the first report demonstrating delayed and prolonged STAT activation coordinated with the loss of SOCS expression in human primary T cells after co-crosslinking of TCR and CD4/CD8 co-receptors.

Keywords: cytokine, Lck, signal transducer and activator of transcription, suppressor of cytokine signaling, T-cell antigen receptor

Introduction

T cell activation involves at least two distinct stages of signal transduction events [1]. Engagement of T-cell antigen receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex upon recognition of a specific antigen in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) or through antibody crosslinking initiates the first signal [2]. CD4/CD8 co-receptors are recruited to the immunological synapse by binding to the MHC and further propagates the signal [3]. CD4/CD8-associated Lck protein tyrosine kinase phosphorylates the zeta-associated protein kinase of 70 kD (ZAP-70) that leads to a cascade of signaling events [4,5]. Multiple signal transduction pathways converge in the nucleus to regulate the expression of specific target genes, including cytokines and cytokine receptors [6]. Most notably, TCR-induced expression of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-2 receptor α chain (IL-2Rα) starts the second wave of signaling events. The secreted IL-2 and the formation of high-avidity IL-2R complex contribute to sequential activation of the receptor-associated Janus kinases (JAK) and downstream signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5). Activated STAT5 proteins translocate to the nucleus and, ultimately, result in T cell proliferation through activation of distinct target genes [7].

Both stages of T cell activation are tightly regulated by coordinated positive and negative regulation [8]. TCR signaling is diminished by dephosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules through different protein tyrosine phosphatases and other regulatory mechanisms. Numerous pathways also contribute to negative regulation of the subsequent JAK-STAT activation downstream of cytokine receptors. Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) is a family of genes best known for their role as a negative feedback regulator of the JAK-STAT pathway [9]. As the first identified SOCS family member, cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CIS) is induced by STAT5 and inhibits further STAT5 activation by competing with STAT5 in binding to cytokine receptors [10]. SOCS1 and SOCS3 are closely related to each other and inhibit JAK kinase activity through direct interaction. Both transgenic and knock-out mouse studies revealed a key role of SOCS1 in T cell development and function [11,12,13]. On the other hand, the effects of CIS and SOCS3 on T cell biology remain largely elusive.

While SOCS proteins are known to inhibit JAK-STAT pathway in response to cytokine stimulation, they are also implicated in the regulation of TCR signaling [14]. Bacterial flagellin-induced SOCS1 interacts with ZAP-70 and inhibits TCR activation [15]. SOCS1 also has been shown to associate with tyrosine-phosphorylated CD3ζ and suppress downstream signaling [16]. Overexpression of SOCS3 blocks TCR signaling by binding to the catalytic subunit of calcineurin and the subsequent inhibition of nuclear factor of activated T cell (NFAT) [17]. These findings suggest a potential cross-talk of negative regulation between TCR signaling and cytokine signaling in modulating T cell functions.

Other than SOCS proteins, STAT5 has been implicated in TCR signaling [18]. It raises the possibility that a cross-talk of positive regulation between TCR and cytokine signaling may also exist. In this report, we specifically examined the status of STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 in resting human peripheral blood T cells in response to the engagement of CD3 and CD4/CD8 co-receptors that strongly activated the Lck kinase. We further examined the expression of endogenous CIS and SOCS3 proteins to evaluate their role in TCR-induced STAT activation. The effect of CIS and SOCS3 on TCR signaling was also determined by the expression of exogenous genes. Results from these studies will provide important insights into the cross-talk of TCR and cytokine signaling in a more physiologically relevant context.

Materials and methods

Cells

Human peripheral blood T cells were isolated from healthy donors as described elsewhere [19]. Mononuclear cells were first isolated by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) gradient centrifugation, followed by monocyte/macrophage depletion via plastic adherence. Nonadherent cells were enriched for T cells by passage through a nylon wool column. Prior to experiments, T cells were rested for additional 24 hours in RPMI supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. The Jurkat T cell line (clone E6-1) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained as previously described [19,20].

Activation of primary T cells

Plastic petri dishes were first coated with 5 μg/ml of rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C, and then blocked with 1% gelatin for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, rabbit IgG-coated dishes were incubated with a mixture of anti-CD3 (OKT3), anti-CD4 (OKT4), and anti-CD8 (OKT8) mouse monoclonal antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) at 1 μg/ml for an additional hour at 4°C. Unbound antibodies were removed by repeated washes with cold PBS. Resting human peripheral blood T cells were added to antibody-coated dishes and incubated at 37°C for various periods of time. Antibody stimulation was terminated by collecting cells on ice and subsequent washes with cold PBS supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4).

For inhibitor analysis, cycloheximide (10 μg/ml), brefeldin A (3 μg/ml), cyclosporine A (1 μM), and FK506 (1 μM) were incubated with human primary T cells for 1 hour before stimulation with plate-bound antibodies. All inhibitors were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). For cytokine stimulation experiments, recombinant human interferon-γ (IFN-γ, 10 ng/ml), IL-2 (1,000 U/ml), and IL-6 (100 U/ml) were added to resting human peripheral blood T cells [19]. After 15 min incubation at 37°C, cells were harvested on ice for subsequent analysis. For neutralization experiments, 10 μg/ml of anti-IFN-γ or anti-IL-6 blocking antibodies were premixed with human primary T cells before stimulation with plate-bound antibodies. The recombinant cytokines and neutralizing antibodies were from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Preparation of nuclear extracts, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and antibody supershift assays were conducted as describer previously [21]. The Sis-inducible element (SIE) and mammary gland element (MGE) consensus oligonucleotides as well as the anti-STAT5 supershifting antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Electroporation

Jurkat T cells were transfected with pEF-FLAG-I without or with full-length mouse CIS and SOCS3 cDNAs [21,22] by electroporation using the Neon transfection system from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). For each transfection, 25 μg of plasmids were mixed with 2 × 106 cells in 100 μl tip setting according to manufacturer’s recommendation. Cells from eight separate electroporation of the same plasmid were pooled together and then recovered in culture media. Twelve hours later, transfected cells were washed twice with cold RPMI and then divided into three equal aliquots. One aliquot was kept as a transfection control. Two other aliquots were incubated on ice without or with 1 μg/ml of anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 for 10 min with frequent mixing. Antibody crosslinking was performed by adding 10 μg/ml of rabbit anti-mouse IgG with additional 10 min incubation on ice. Cells with or without antibody crosslinking were stimulated at 37°C for 3 min. Antibody stimulation was terminated by washing the cells twice with cold PBS supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Human primary T cells and Jurkat T cells were lysed by RIPA buffer. Normalized whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as described before [23]. Dilutions of different antibodies for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as well as subsequent detection by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and the LI-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system (Lincoln, NE) were performed as recommended by the manufacturers. Anti-CIS, anti-SOCS3, and anti-ZAP-70 antibodies for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Anti-FLAG M2 and anti-phosphotyrosine 4G10 monoclonal antibodies used for immunoblotting were from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. and Millipore (Billerica, MA), respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for ECL were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. IRDye-conjugated secondary antibodies for Odyssey imaging analysis were from Rockland, Inc. (Gilbertsville, PA).

Results and discussion

Delayed and prolonged STAT activation in response to TCR stimulation

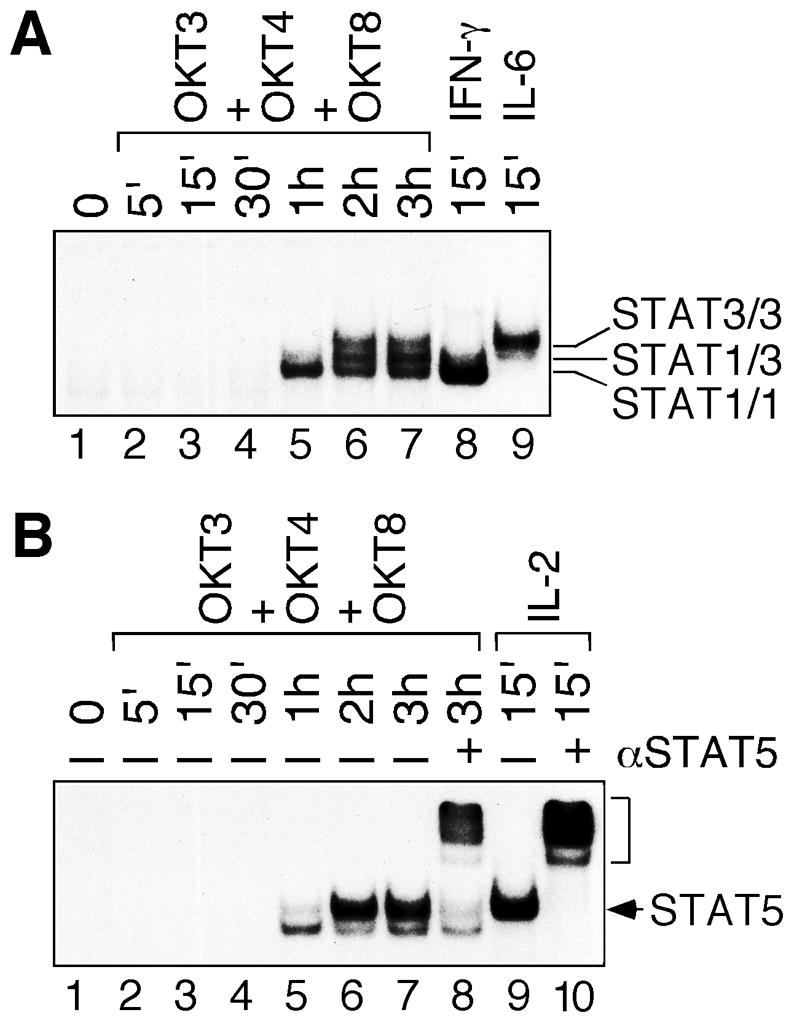

We showed previously that STAT3 and STAT5 were activated in cells transformed by oncogenic Lck [19,24]. To maximally activate Lck kinase in the context of TCR complex, we stimulated resting human peripheral blood T cells with plate-bound antibodies against human CD3, CD4 and CD8 [25]. As shown in Fig. 1A, STAT1 and STAT3 DNA-binding activity was detected 1 and 2 hours after TCR stimulation, respectively (lanes 5 and 6). Moreover, STAT1 and STAT3 activation was sustained for 3 (lane 7) to 8 hours (not shown). As controls, human primary T cells were stimulated with recombinant human IFN-γ and IL-6, respectively, for 15 min to show the positions of STAT1 homodimers (lane 8) and STAT3 homodimers (lane 9). Supershift assay with antibodies specific for STAT1 and STAT3 further confirmed the presence of STAT1 and STAT3, respectively, in the DNA-protein complexes (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Delayed and prolonged STAT activation in human primary T cells after TCR stimulation. Human peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with plate-bound OKT3, OKT4 and OKT8 antibody mixture from 5 min (5′) to 3 hours (3h). T cells were also stimulated with recombinant human IFN-γ, IL-6 or IL-2 for 15 min. Nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA with a 32P-labeled SIE (A) or MGE (B) consensus probe. The positions of specific STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 DNA-binding activity are marked on the right. Antibody supershift experiments were performed in the presence of anti-STAT5 antibody (αSTAT5). The bracket on the right indicates the position of supershifted STAT5-DNA complex.

Similar to STAT1, STAT5 DNA-binding activity was detectable 1 hour after TCR stimulation (Fig. 1B, lane 5). Maximal STAT5 activation was observed 2 hours after TCR stimulation and sustained for 3 (lane 7) to 8 hours (not shown). Supershift assay with STAT5-specific antibody confirmed the presence of STAT5 mostly in the upper, but not the lower, DNA-protein complex (compare lanes 7 and 8). In contrast to the delayed STAT5 activation by TCR stimulation, high dose of IL-2 activated STAT5 within 15 min in human primary T cells (lane 9). IL-2-induced STAT5 DNA-binding activity co-migrated with the upper band in TCR-stimulated cells and could be supershifted by anti-STAT5 antibody (lane 10).

Our data do not support the role of STAT as a signaling molecule in the TCR complex. Contradicting results were reported previously in mouse T cells on the role of STAT5 in TCR signaling through crosslinking with anti-CD3 antibody alone [18,26]. We believe that our studies of resting human peripheral blood T cells in response of CD3/CD4/CD8 co-crosslinkling more closely resemble the physiological contact between T cells and the antigen/MHC complex. Furthermore, our results show that STAT1 activation precedes STAT3 and STAT5 activation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of sequential STAT activation in response to co-crosslinking of TCR and CD4/CD8 co-receptors in human primary T cells.

Autocrine and/or paracrine-induced STAT activation

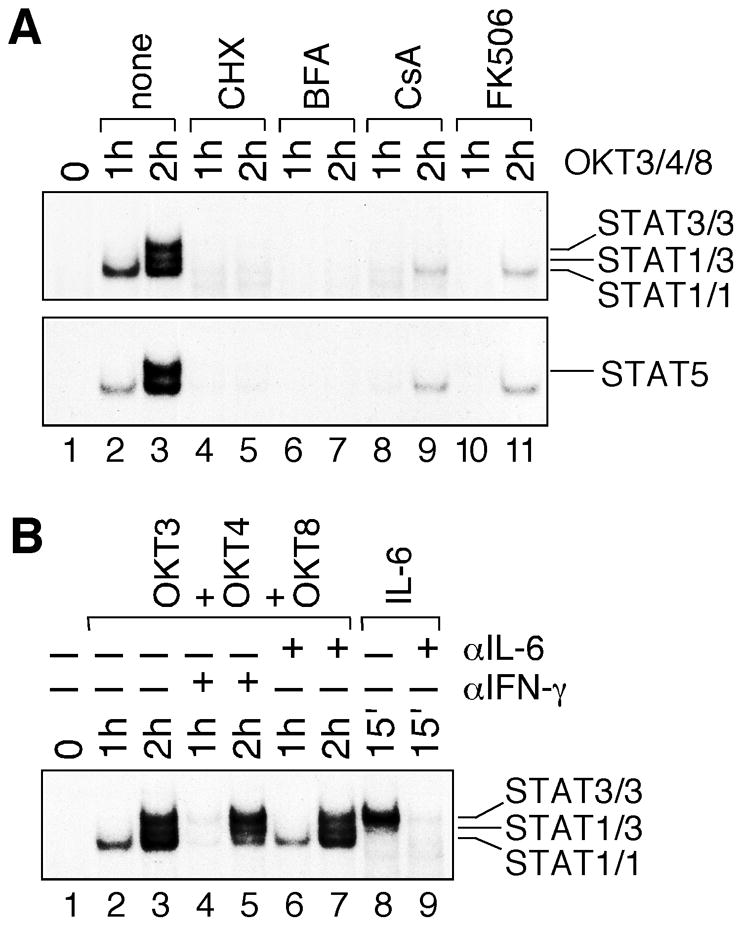

Delayed STAT activation in TCR-stimulated cells suggested that STAT activation was not a proximal event downstream of TCR/CD4/CD8 complex. As shown in Fig. 2A, pretreatment with both cycloheximide (a protein synthesis inhibitor) and brefeldin A (a protein secretion inhibitor) completely abolished the activation of STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 in TCR-stimulated human primary T cells (lanes 4–7). It clearly demonstrates that new protein synthesis and secretion are essential for STAT activation following TCR stimulation. Cyclosporine A and FK506 are two potent immunosuppressant that block TCR signaling by inhibiting calcineurin-dependent signal transduction in T cells [27]. Similarly, they both greatly reduced STAT activation in TCR-stimulated human primary T cells (lanes 8–11). All together, these results strongly support the role of autocrine/paracrine stimulation in delayed STAT activation in human primary T cells upon engagement of TCR and CD4/CD8 co-receptors.

Fig. 2.

Involvement of cytokines in TCR-induced STAT activation. (A) Human peripheral blood T cells were either left untreated (lanes 1–3) or treated with cycloheximide (CHX), brefeldin A (BFA), cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506 (lanes 4–11) for 1 hour, and then stimulated with plate-bound OKT3, OKT4 and OKT8 antibody mixture for 1 and 2 hours. Nuclear extracts containing the same amounts of total proteins were analyzed by EMSA using 32P-labeled SIE (upper panel) and MGE (lower panel) consensus probes. (B) Human peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with plate-bound OKT3, OKT4 and OKT8 antibody mixture either in the absence (lanes 2 and 3) or presence of anti-IFN-γ (lanes 4 and 5) and anti-IL-6 (lanes 6 and 7) neutralizing antibodies. Human primary T cells were also stimulated with recombinant human IL-6 without (lane 8) or with (lane 9) pre-incubation with anti-IL-6 neutralizing antibody at 37°C for 1 hour. Nuclear extracts were examined by EMSA with 32P-labeled SIE consensus probe.

Previous studies implicated autocrine stimulation of STAT proteins by IFN-γ and IL-6 in TCR-stimulated human T cells [28,29]. Consistent with these reports, recombinant human IFN-γ and IL-6 strongly activated STAT1 and STAT3, respectively, in human primary T cells (Fig. 1A). To determine whether they contribute to delayed STAT1 and STAT3 activation in human primary T cells, we utilized antibodies that specifically neutralize human IFN-γ and IL-6. As shown in Fig. 2B, IFN-γ-neutralizing antibody greatly diminished STAT1, but not STAT3, DNA-binding activity (lanes 4 and 5). On the other hand, IL-6-neutrlizing antibody had no significant effect on both STAT1 and STAT3 DNA-binding activity (lanes 6 and 7). As a positive control, the same IL-6-neutralizing antibody completely abolished IL-6-induced STAT3 activation (compare lanes 8 and 9). Therefore, while IFN-γ is the major cytokine that activates STAT1 in TCR-stimulated human primary T cells, the cytokine(s) responsible for STAT3 activation remain to be determined.

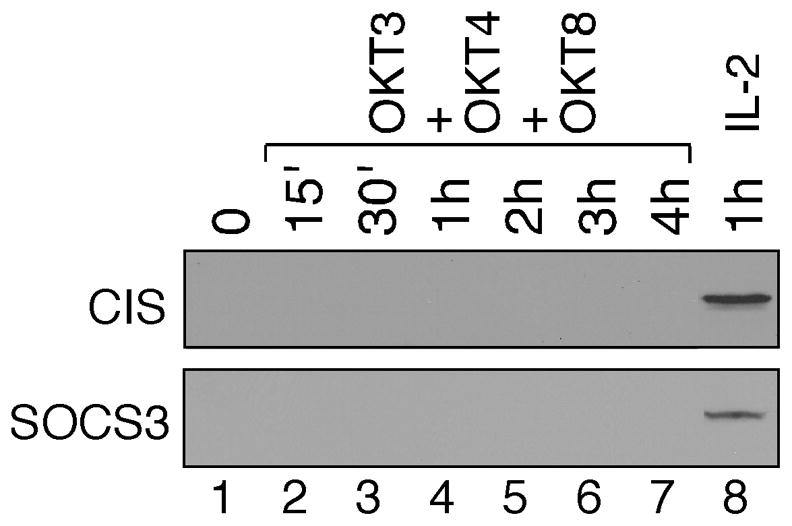

Absence of endogenous SOCS gene expression after TCR stimulation

SOCS proteins are the key negative feedback regulators of JAK-STAT signaling in response to cytokine stimulation [30]. We showed previously that both CIS and SOCS3 were not expressed in leukemic T cells that exhibited constitutive STAT3 and STAT5 activation [21,22]. It raises the possibility that absence of CIS and SOCS3 expression may also contribute to prolonged STAT activation in TCR-stimulated human primary T cells (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 3, endogenous CIS and SOCS3 proteins were undetectable in TCR-stimulated human primary T cells (lanes 1–7). As a positive control, both CIS and SOCS3 were induced in IL-2-stimulated T cells (lane 8), which is consistent with the transient kinetics of STAT5 activation [31].

Fig. 3.

The absence of CIS and SOCS3 expression in TCR-stimulated human primary T cells. Human peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with plate-bound OKT3, OKT4 and OKT8 antibody mixture (lanes 2–7) for 15 min to 4 hours or with recombinant human IL-2 for 1 hour (lane 8). Normalized whole cell lysates prepared from unstimulated (lane 1) and stimulated T cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using anti-CIS (upper panel) and anti-SOCS3 (lower panel) antibodies.

CIS is one of the best-characterized STAT5-target genes and plays a key role in the negative feedback control of STAT5 activity in response to cytokine stimulation [32]. The absence of CIS expression in human primary T cells after co-stimulation of CD3, CD4 and CD8 may contribute to prolonged STAT5 activation (Fig. 1B). Similar observation was also reported in TCR-stimulated mouse primary T cells [26]. On the other hand, SOCS3 has been shown to down-regulate STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 activity upon cytokine stimulation [33]. Therefore, the absence of SOCS3 expression may contribute to sustained STAT1 and STAT3 activation (Fig. 1A). More importantly, these findings suggest that cytokine signaling is distinctly different with or without prior TCR stimulation in human primary T cells. It is plausible that the initial engagement of TCR and CD4/CD8 co-receptors may trigger a temporary repression on SOCS gene induction.

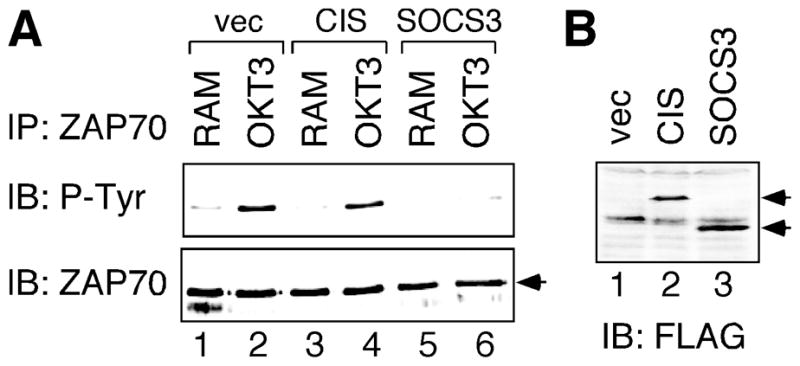

Suppression of TCR signaling by enforced SOCS gene expression

The observation that both CIS and SOCS3 were not expressed in TCR-stimulated cells prompted us to further examine the effects of exogenous CIS and SOCS3 on TCR signaling. Due to the difficulty in transfecting primary human T cells, we transfected FLAG-tagged CIS and SOCS3 into the human Jurkat T cells, a well-established model cell line in studying TCR signaling. ZAP-70 is the key substrate of Lck kinase in response to TCR engagement. As shown in Fig. 4A, ZAP-70 became tyrosine phosphorylated within 3 min of CD3 crosslinking (compare lanes 1 and 2). Even though both CIS and SOCS3 proteins were expressed in transfected Jurkat T cells (Fig. 4B), tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 was only diminished in cells expressing SOCS3, but not CIS (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 4 and 6). This result suggests that SOCS3 can also suppress Lck kinase activity in the context of TCR signaling.

Fig. 4.

Suppression of TCR signaling by enforced SOCS3 expression. Human Jurkat T cells were transfected with CIS or SOCS3 expression constructs, or vector control (vec). (A) Transfected cells were stimulated by anti-CD3 antibody and rabbit anti-mouse (RAM) antibody crosslinking for 3 min (lanes 2, 4, 6). As negative controls, transfected cells were also stimulated with rabbit anti-mouse antibody alone for 3 min (lanes 1, 3, 5). Normalized whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-ZAP-70 antibody, followed by sequential blotting (IB) with antibodies specific for phosphotyrosine (P-Tyr) and ZAP-70. (B) Normalized whole cell lysates prepared from aliquots of transfected cells were analyzed by anti-FLAG immunoblotting to confirm expression of exogenous SOCS proteins. The arrows on the right show the correct positions of CIS (lane 2) and SOCS3 (lane 3) proteins.

SOCS1 is the SOCS family member most closely related to SOCS3 and has been shown to block TCR signaling through interaction with Syk and CD3ζ [16]. Our data suggest that SOCS3 may target directly at the TCR complex through a similar mechanism. Consistent with the role of SOCS3 as a TCR repressor, overexpression and knock-down experiments showed that SOCS3 negatively regulated TCR-induced proliferation of mouse Th cells [34]. On the contrary, CIS overexpression promotes TCR-mediated proliferation of mouse CD4 T cells [35]. Our studies showed that, in human primary T cells, ectopic CIS expression had no effect on proximal TCR signaling (Fig. 4). It suggests that CIS may act further downstream of TCR signal transduction pathways, such as on protein kinase C [35]. Collectively, these results demonstrate diverse functions of distinct SOCS family members in the regulation of T cell signaling.

In summary, our data indicate that STAT5 is not a direct target of CD4/CD8-associated Lck kinase in the context of normal TCR signaling. Similarly, STAT1 and STAT3 do not participate in the signaling events proximal to the TCR complex. Instead, autocrine/paracrine subsequent to TCR stimulation leads to sequential STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 activation. The prolonged STAT activation correlates with the absence of CIS and SOCS3 expression. These findings demonstrate important differences between CD4/CD8-associated Lck and oncogenic Lck kinases. They also point to the distinct intracellular environment in naïve primary T cells with regard to SOCS protein expression.

Research Highlights.

CD3/4/8 engagement induces sequential STAT1/3/5 activation in human primary T cells.

Delayed STAT activation is due to autocrine/paracrine stimulation.

IFN-γ contributes to STAT1 activation in TCR-stimulated cells.

Prolonged STAT activation correlates with the absence of CIS and SOCS3 proteins.

Exogenous SOCS3, but not CIS, inhibits TCR signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tracy Willson (WEHI, Australia) for the CIS and SOCS3 cDNA constructs. We would also like to give our special thanks to Dr. Steven J. Burakoff (Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY) for reagents and technical support. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant CA107210 and RFUMS H. M. Bligh Cancer Research Fund (to C.L. Yu).

Abbreviations used

- TCR

T-cell antigen receptor

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- ZAP-70

zeta-associated protein kinase of 70 kD

- IL

interleukin

- JAK

Janus kinase

- SOCS

suppressor of cytokine signaling

- CIS

cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cell

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- IFN

interferon

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- SIE

Sis-inducible element

- MGE

mammary gland element

- ECL

enhanced chemiluminescence

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fooksman DR, Vardhana S, Vasiliver-Shamis G, Liese J, Blair DA, Waite J, Sacristan C, Victora GD, Zanin-Zhorov A, Dustin ML. Functional anatomy of T cell activation and synapse formation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierer BE, Sleckman BP, Ratnofsky SE, Burakoff SJ. The biologic roles of CD2, CD4, and CD8 in T-cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:579–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salmond RJ, Filby A, Qureshi I, Caserta S, Zamoyska R. T-cell receptor proximal signaling via the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, influences T-cell activation, differentiation, and tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:9–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu DH, Morita CT, Weiss A. The Syk family of protein tyrosine kinases in T-cell activation and development. Immunol Rev. 1998;165:167–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nel AE, Slaughter N. T-cell activation through the antigen receptor. Part 2: role of signaling cascades in T-cell differentiation, anergy, immune senescence, and development of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:901–915. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriggl R, Topham DJ, Teglund S, Sexl V, McKay C, Wang D, Hoffmeyer A, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, Bunting KD, Grosveld GC, Ihle JN. Stat5 is required for IL-2-induced cell cycle progression of peripheral T cells. Immunity. 1999;10:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koretzky GA, Myung PS. Positive and negative regulation of T-cell activation by adaptor proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:95–107. doi: 10.1038/35100523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer DC, Restifo NP. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) in T cell differentiation, maturation, and function. Trend Immunol. 2009;30:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshimura A, Ohkubo T, Kiguchi T, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Hara T, Miyajima A. A novel cytokine-inducible gene CIS encodes an SH2-containing protein that binds to tyrosine-phosphorylated interleukin 3 and erythropoietin receptors. EMBO J. 1995;14:2816–2826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto M, Naka T, Nakagawa R, Kawazoe Y, Morita Y, Tateishi A, Okumura K, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Defective thymocyte development and perturbed homeostasis of T cells in STAT-induced STAT inhibitor-1/suppressors of cytokine signaling-1 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:1799–1806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornish AL, Davey GM, Metcalf D, Purton JF, Corbin JE, Greenhalgh CJ, Darwiche R, Wu L, Nicola NA, Godfrey DI, Heath WR, Hilton DJ, Alexander WS, Starr R. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 has IFN-gamma-independent actions in T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2003;170:878–886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trop S, De Sepulveda P, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Rottapel R. Overexpression of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 impairs pre-T-cell receptor-induced proliferation but not differentiation of immature thymocytes. Blood. 2001;97:2269–2277. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher J, Starr R. The role of suppressors of cytokine signalling in thymopoiesis and T cell activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1774–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okugawa S, Yanagimoto S, Tsukada K, Kitazawa T, Koike K, Kimura S, Nagase H, Hirai K, Ota Y. Bacterial flagellin inhibits T cell receptor-mediated activation of T cells by inducing suppressor of cytokine signalling-1 (SOCS-1) Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1571–1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda T, Yamamoto T, Kishi H, Yoshimura A, Muraguchi A. SOCS-1 can suppress CD3zeta- and Syk-mediated NF-AT activation in a non-lymphoid cell line. FEBS Lett. 2000;472:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee A, Banks AS, Nawijn MC, Chen XP, Rothman PB. Cutting edge: Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 inhibits activation of NFATp. J Immunol. 2002;168:4277–4281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welte T, Leitenberg D, Dittel BN, al-Ramadi BK, Xie B, Chin YE, Janeway CA, Jr, Bothwell AL, Bottomly K, Fu XY. STAT5 interaction with the T cell receptor complex and stimulation of T cell proliferation. Science. 1999;283:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu CL, Jove R, Burakoff SJ. Constitutive activation of the Janus kinase-STAT pathway in T lymphoma overexpressing the Lck protein tyrosine kinase. J Immunol. 1997;159:5206–5210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chueh FY, Leong KF, Yu CL. Mitochondrial translocation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) in leukemic T cells and cytokine-stimulated cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:778–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper JC, Shi M, Chueh FY, Venkitachalam S, Yu CL. Enforced SOCS1 and SOCS3 expression attenuates Lck-mediated cellular transformation. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:1201–1208. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper JC, Boustead JN, Yu CL. Characterization of STAT5B phosphorylation correlating with expression of cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CIS) Cell Signal. 2006;18:851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkitachalam S, Chueh FY, Leong KF, Pabich S, Yu CL. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 interacts with oncogenic lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:677–683. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi M, Cooper JC, Yu CL. A Constitutively Active Lck Kinase Promotes Cell Proliferation and Resistance to Apoptosis through Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5b Activation. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:39–45. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravichandran KS, Pratt JC, Sawasdikosol S, Irie HY, Burakoff SJ. Coreceptors and adapter proteins in T-cell signaling. Anna NY Acad Sci. 1995;766:117–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb26656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriggl R, Sexl V, Piekorz R, Topham D, Ihle JN. Stat5 activation is uniquely associated with cytokine signaling in peripheral T cells. Immunity. 1999;11:225–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bierer BE, Hollander G, Fruman D, Burakoff SJ. Cyclosporin A and FK506: molecular mechanisms of immunosuppression and probes for transplantation biology. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:763–773. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90135-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girdlestone J, Wing M. Autocrine activation by interferon-gamma of STAT factors following T cell activation. Eu J Immunol. 1996;26:704–709. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henttinen T, Levy DE, Silvennoinen O, Hurme M. Activation of the signal transducer and transcription (STAT) signaling pathway in a primary T cell response. Critical role for IL-6. J Immunol. 1995;155:4582–4587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen XP, Losman JA, Rothman P. SOCS proteins, regulators of intracellular signaling. Immunity. 2000;13:287–290. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu CL, Jin YJ, Burakoff SJ. Cytosolic tyrosine dephosphorylation of STAT5. Potential role of SHP-2 in STAT5 regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:599–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshimura A. Negative regulation of cytokine signaling. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:205–220. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Sullivan LA, Liongue C, Lewis RS, Stephenson SEM, Ward AC. Cytokine receptor signaling through the Jak-Stat-Socs pathway in disease. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2497–2506. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu CR, Mahdi RM, Ebong S, Vistica BP, Gery I, Egwuagu CE. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 regulates proliferation and activation of T-helper cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29752–29759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li S, Chen S, Xu X, Sundstedt A, Paulsson KM, Anderson P, Karlsson S, Sjogrenn HO, Wang P. Cytokine-induced Src homology 2 protein (CIS) promotes T cell receptor-mediated proliferation and prolongs survival of activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:985–994. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]