Abstract

Background

Currently, a new generation of synthetic pulmonary surfactants is being developed that may eventually replace animal-derived surfactants used in the treatment of respiratory distress syndrome. Enlightened by this, we prepared a synthetic peptide-containing surfactant (Synsurf) consisting of phospholipids and poly-l-lysine electrostatically bonded to poly-l-glutamic acid. Our objective in this study was to investigate if bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)-induced acute lung injury and surfactant deficiency with accompanying hypoxemia and increased alveolar and physiological dead space is restored to its prelavage condition by surfactant replacement with Synsurf, a generic prepared Exosurf, and a generic Exosurf containing Ca2+.

Methods

Twelve adult New Zealand white rabbits receiving conventional mechanical ventilation underwent repeated BAL to create acute lung injury and surfactant-deficient lung disease. Synthetic surfactants were then administered and their effects assessed at specified time points over 5 hours. The variables assessed before and after lavage and surfactant treatment included alveolar and physiological dead space, dead space/tidal volume ratio, arterial end-tidal carbon dioxide tension (PCO2) difference (mainstream capnography), arterial blood gas analysis, calculated shunt, and oxygen ratios.

Results

BAL led to acute lung injury characterized by an increasing arterial PCO2 and a simultaneous increase of alveolar and physiological dead space/tidal volume ratio with no intergroup differences. Arterial end-tidal PCO2 and dead space/tidal volume ratio correlated in the Synsurf, generic Exosurf and generic Exosurf containing Ca2+ groups. A significant and sustained improvement in systemic oxygenation occurred from time point 180 minutes onward in animals treated with Synsurf compared to the other two groups (P < 0.001). A statistically significant decrease in pulmonary shunt (P < 0.001) was found for the Synsurf-treated group of animals, as well as radiographic improvement in three out of four animals in that group.

Conclusion

In general, surfactant-replacement therapy in the animals did not fully restore the lung to its prelavage condition. However, our data show that the formulated surfactant Synsurf improves oxygenation by lowering pulmonary shunt.

Keywords: pulmonary surfactant, synthetic peptides, respiratory dead space, capnometry, pulmonary gas exchange, oxygenation

Introduction

Surfactant-replacement therapy with animal-derived surfactant preparations is an established treatment modality for respiratory distress syndrome that revolutionized the care of preterm babies in intensive care units.1,2 Pulmonary surfactant is a complex mixture of phospholipids and at least four apoproteins that reduces surface tension at the alveolar surface.3 The mixture has unique spreading properties, promotes lung expansion during inspiration, and prevents lung collapse during expiration. Of all the protein components in the mixture, the hydrophobic surfactant proteins B (SP-B) and C (SP-C) have an essential function in the spreading, adsorption, and stability of surfactant lipids.4–6

Over the past decade, natural and synthetic surfactants have extensively been tested with regard to their in vitro properties and in vivo physiologic effects.1 Unfortunately, synthetic products have lost popularity in favor of natural products that contain low concentrations of SP-B and SP-C, which are essential for adsorption and spreading of the surfactant film at the air–liquid interface. However, commercially the large-scale production and supply of natural surfactants are not only time-consuming and expensive with a limited supply, but there are concerns about the reproducibility and purity and the possibility of transmission of infectious material.7 The development of an effective artificial surfactant mixture, devoid of foreign protein, that can be prepared in large quantities at a reasonable cost remains challenging. Moreover, a common denominator in acute lung diseases is inactivation of surfactant by plasma and other components. Much work is therefore aimed at constructing a new generation of synthetic surfactants that will be more resistant towards inactivation.

Various research groups have chemically prepared peptides with amino acid sequences based on that of SP-B. In two such studies, the treatment of preterm infant rhesus monkeys and human infants with respiratory distress syndrome was demonstrated with a peptide/phospholipid mixture (KL4-surfactant).8,9 In both studies, this synthetic surfactant expanded the pulmonary alveoli and promoted gas exchange. Based on such a design, we prepared a surfactant consisting of the phospholipids dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and two polymers: poly.lysine electrostatically complexed with poly-l-glutamic acid (Syn-surf [S]). The polymers were added to the phospholipids, in order to mimic the hydrophobic and hydrophilic nature of SP-B in the mixture.

In this study, we were particularly interested to compare the efficacy of S as a synthetic surfactant in a comparative study with a previously used synthetic protein-free surfactant, Exosurf Neonatal10,11 (we prepared a generic version), hereafter named GE. Although similar in chemical composition, we cannot guarantee that the GE used in our experiments was identical to commercially manufactured Exosurf Neonatal, as it was discontinued at the time of the present study. However, in a previous study12 before its discontinuation, we were able to compare the in vivo efficacy of our GE and its physiological effects and gas-exchange capabilities with the then-available commercial Exosurf Neonatal product. Although we found differences that we could not provide plausible explanations for in the on-site formulations, the overall outcome in performance was similar to Exosurf Neonatal. Moreover, the surface tension-lowering ability of the GE preparations were not significantly different to that of Exosurf Neonatal when we tested them.13 In the present study, we also found that the surface-lowering ability of GE and S is virtually similar. Although surface-tension measurements strongly depend on the technique applied our data, measured under dynamic conditions, are in agreement with the less effective surface tension-lowering ability reported by others in the absence of SP-B and SP-C.14

Considering reports in literature1516 that bivalent cations such as Ca2+ can increase the speed of surface adsorption of surfactant molecules and to stabilize films in experimental conditions, we decided to include a GE preparation mixed with Ca2+ (GECa2+) to elucidate the beneficial effect. Hence we tested the efficacy of three surfactant preparations in an adult rabbit model with acute lung injury and surfactant deficiency. We tested the hypothesis that a synthetic peptide-containing surfactant (S) would improve systemic oxygenation and restore the surfactant-deficient lungs to prelavage condition after surfactant depletion was induced by repeated bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in comparison to two synthetic surfactants devoid of protein.

Materials and methods

DPPC was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). PG, cetyl alcohol, tyloxapol, poly-L-lysine (molecular weight 16.1 kDa) and poly-L-glutamic acid (molecular weight 12 kDa) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Phospholipid purity was verified by thin-layer chromatography17 Sterile water for injection was used in the preparation of surfactant. Chloroform used was high-performance liquid chromatography-grade (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Experimental surfactant preparations

Synsurf (S) was prepared by mixing DPPC, hexadecanol, and PG in a 10:1.1:1 ratio (w/w) in chloroform. The organic solvent was then removed by rotary evaporation and the mixture was dried under a continuous stream of nitrogen at room temperature. Poly-l-lysine (~100–120 residues) was mixed with poly-l-glutamate (approximately 80 residues) and incubated at 3°C in 0.1 M NaCl to give a complex that was 50% neutralized. The complex was prepared in such a manner as to be positively charged through having an excess of poly-l-lysine residues. The dried phospholipid film was then hydrated with the polymer mixture (3% by weight of the phospholipid concentration) and gently mixed in the presence of glass beads. A Branson (Danbury CT, USA) B-15P ultrasonicater fitted with a microtip was then used to sonicate the mixture on ice under a stream of nitrogen (power of 20 watts for 7 × 13 seconds; 60-second intervals). Hereafter, 24 mg of tyloxapol was added to the preparation, and the tube was sealed under nitrogen before use. The GE surfactant was also prepared in a similar fashion as described above and consisted of three components: DPPC/hexadecanol/tyloxapol (13.5:1.5:1) in 0.1 M NaCl. The dose of S, GE, and GECa2+ used was 100 mg/kg. CaCl2 included in GECa2+ amounted to 5 mM.

Animal preparation

Animal care and experimental procedures were performed under approval from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Committee of Stellenbosch University. Adult New Zealand white rabbits weighing 2.5–3.75 kg ± 0.39 kg were premedicated with ketamine (25–50 mg/kg). They were positioned on their back and kept in this position throughout the experiment. An auricular intravenous line was inserted and an infusion (5 mL/kg/hour) with a Ringer’s glucose solution started. Animals then underwent tracheostomy, and an uncuffed endotracheal tube (size 2.5–4.0 mm) was inserted and firmly tied to exclude air leaks. Intravenous pentobarbital (6 mg/kg body weight) and pancuronium bromide (0.1 mg/kg body weight) were administered. Anesthesia was maintained with an infusion of sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 6 mg/kg/hour. The left carotid artery was catheterized for arterial blood gas measurements and hemodynamic monitoring (blood pressure and pulse rate). Lidocaine (1%) was used for local anesthesia at surgical sites. Animals were ventilated using the time-cycled pressure-limited mode (Julian Anaesthetic Workstation; Dräger, Lübeck, Germany) at a peak inspiratory pressure necessary to maintain a tidal volume (VT) of 10 mL/kg and partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) between 4 and 7.5 kPa (30–56 mmHg). The VT of a spontaneously breathing young adult rabbit (2.775 ± 0.198 kg) varies between 19 and 25 mL, and the mean PaCO2 for rabbits weighing 2.9–3.5 kg (in the absence of ketamine) is 31.8 ± 1.7 mmHg (4.2 ± 0.22 kPa).18,19 Using the same model, VT varying between 8 and 12 mL/kg resulting in partial arterial pressure of CO2 between 4.5 and 5.3 kPa have been reported.20–22 However, since a body of researchers used VT of 10 mL/kg in adult rabbits, we decided to standardize our protocol accordingly.23–27 This VT was verified by a combined neonatal CO2/flow sensor (CO2SMO plus respiratory profile monitor model 8000; Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, CT, USA). At the moment of the incision of the trachea, continuous intravenous infusion of pentobarbital sodium was commenced (6 mg/kg/hour). Neuromuscular paralysis was achieved by administering intravenous pancuronium bromide (0.1 mg/kg) on an hourly basis. The rectal temperature was monitored, and the aim was to keep it between 38°C and 40°C with an electrical heating pad. The reported normal range of rectal temperatures in the rabbit is 38.6°C–40.1°C.19 The blood pressure transducer was intermittently flushed with saline containing heparin 5 IU heparin/mL. The blood pressure of the healthy rabbit varies between 90–130 (systolic) and 60–91 (diastolic) mmHg.19 The depth of anesthesia was intermittently checked by pinching the web of a hind-leg paw to create a painful stimulus, and by the flow sensor to check for spontaneous breathing efforts. The study lasted 5 hours before the animals were killed by a lethal intra-arterial injection of 15% potassium chloride.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and surfactant treatment

Animals were subjected to repeated warm saline (37°C) lavage (20 mL/kg) via the endotracheal tube, similar to the technique described by Lachmann et al.28 Lavage end points included a decrease in arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) to below 11 kPa (fraction of inspiratory oxygen [FiO2] 1.0) and a decrease in dynamic respiratory compliance (Cdyn) by 40% or more. The total volume of lavage fluid (corrected for body weight) necessary to achieve significant surfactant deficiency/acute lung injury was recorded together with the volume retrieved. The retrieved volume was expressed as a percentage of the instilled volume. A 10-minute period was allowed for stabilization following lavage, and then animals were randomized into three treatment groups. Group A received the GE protein-free surfactant, group B the GE plus Ca2+ (5 mM), and group C the peptide-containing surfactant (Synsurf, InnovUS, Stellenbosch University) via the endotracheal tube (DPPC concentration 100 mg/kg).

Measurement of lung mechanics, capnometry, and arterial blood gases

The FiO2 (1.0), VT (aim 10 mL/kg), respiratory rate (40 breaths per minute, spontaneous breathing rate of a rabbit varies between 32 and 60/minute), positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP: 5 cmH2O after lavage), and the inspiratory time (TI):expiratory time (TE) at 1:1.5 (TI 0.6 seconds, TE 0.9 seconds) were kept constant throughout the study. Arterial blood gases (Radiometer ABL 500 blood gas analyzer; Regent Medic, London, UK), pulmonary functions (dynamic expiratory airway resistance [Rawe], VT, Cdyn), ventilator settings, physiological parameters (rectal temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate), oxygenation, capnometry, and other calculations were recorded/measured before and after lavage and at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 300 minutes after surfactant-replacement therapy. Oxygenation variables were calculated. The arterial/alveolar (a/A) ratio = PaO2/(PB − 47) FiO2 − PaCO2/R (R assumed respiratory quotient 0.8). Pulmonary function and CO2 measurements were measured with the CO2SMO Plus respiratory profile monitor. The low dead-space measurement chamber with flow sensor was placed inbetween the ventilator circuit wye and endotracheal tube adaptor. The CO2SMO Plus monitor measures and displays respiratory mechanics and carbon dioxide data and calculates flow, CO2, and oximetry-related parameters. Flow-sensor calibration was not necessary, since the device automatically zeroed periodically by internal values. Partial pressure of end-tidal carbon dioxide tension (PETCO2) was measured by mainstream infrared absorption. By using the tension of carbon dioxide (PCO2) and volume measurements, the anatomic dead space, alveolar dead space (VDalv), physiological dead space, physiological dead space/VT ratio, and VDalv/VT ratio were determined. The arterial end-tidal PCO difference (P[a-et]CO2) was obtained by subtracting the PetCO2 from PaCO2 of an arterial blood gas sample. The shunt was calculated as follows: Qs/Qt = 88.77 − 2.4 (20.4 log PaO2/FiO2).29

Chest radiography

Anteroposterior chest radiographs were taken prior to lavage, immediately prior to randomization, and at the end of the study. The distance between the probe and film was kept at 24 cm. Changes in lung fields were assessed in a blinded manner in regard to whether the radiographic opacification following lavage (atelectasis) resolved (better), remained unchanged (similar), or deteriorated (worse).

Statistical methods

One-way analysis of variance and linear mixed-effects modeling were used as described by Pinheiro et al30 and Maritz et al.31 Variables measured for groups at the predetermined time points were also compared using unpaired t-tests. For continuous variables measured over time, a linear regression of the variables over time by least-squares analysis was used to compare groups by differences in the initial responses to surfactant (y-intercepts) and change over time (slopes). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. A P-value < 0.05 was taken as significant (Statistica version 10; StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). GraphPad (La Jolla, CA, USA) Prism 5 was used to determine correlations.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean (± standard deviation) values for weight and prelavage mean arterial blood pressure, arterial blood gases, capnometry, and pulmonary functions are shown in Table 1. The total volume of lavage fluid required to induce acute lung injury and surfactant deficiency (S 74.75 ± 17.04 mL, GE 73.58 ± 21.2 mL, GECa2+ 73.58 ± 21.2 mL) and the percentage of fluid retrieved from the airways (lavage %: S 86.5% ± 6.73%; GE 79.38% ± 7.70%; GEca2+ 79.25% ± 3.30%) did not differ between the groups. The end points of lavage were similar between the groups. Although the aim was to randomize the individual animals 10 minutes after the final lavage and after the chest X-ray was performed in reality, the randomization occurred at 9 ± 3.16 minutes. There were no intergroup differences.

Table 1.

Results before bronchoalveolar lavage at 3 hours and 5 hours after surfactant treatment in twelve rabbits

| Variable | Synsurf group (n = 4) | Exosurf group (n = 4) | Exosurf + Ca2+ group (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 3.13 ± 0.56 | 2.95 ± 0.19 | 3.44 ± 0.24 |

| Pre-VT (mL/kg) | 10.08 ± 0.29 | 10.20 ± 0.58 | 10.03 ± 0.35 |

| 180 minutes | 10.08 ± 0.17 | 9.85 ± 0.21 | 10.13 ± 0.19 |

| 300 minutes | 10.05 ± 0.10 | 9.75 ± 0.24 | 9.93 ± 0.22 |

| Pre-MABP (mmHg) | 82.60 ± 4.07 | 92.40 ± 3.83 | 91.50 ± 7.51 |

| 180 minutes | 89.50 ± 11.21 | 100.30 ± 6.99 | 93.25 ± 4.72 |

| 300 minutes | 87.00 ± 15.12 | 96.75 ± 12.2 | 91.00 ± 14.67 |

| Pre-PaO2 (mmHg) | 499.70 ± 9.46 | 511.10 ± 17.38 | 509.30 ± 24.08 |

| Post- | 57.95 ± 14.90 | 53.25 ± 15.97 | 50.81 ± 18.30 |

| 180 minutes | 152.30 ± 49.27 | 85.69 ± 25.85 | 109.90 ± 46.32 |

| 300 minutes | 281.30 ± 47.64 | 74.25 ± 8.84 | 85.69 ± 32.56 |

| Pre-a/A ratio | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.03 |

| Post- | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.03 |

| 180 minutes | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.07 |

| 300 minutes | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.05 |

| Pre-PaCO2 (mmHg) | 40.69 ± 3.15 | 39.38 ± 6.26 | 36.19 ± 8.04 |

| 180 minutes | 38.44 ± 4.99 | 38.63 ± 5.49 | 36.19 ± 4.99 |

| 300 minutes | 36.75 ± 2.12 | 40.13 ± 4.18 | 38.81 ± 7.15 |

| Pre-PetCO2 (mmHg) | 14.25 ± 3.06 | 14.63 ± 3.09 | 13.88 ± 1.3 |

| 180 minutes | 9.56 ± 1.88 | 10.13 ± 2.17 | 10.69 ± 0.94 |

| 300 minutes | 9.75 ± 1.50 | 9.38 ± 1.44 | 9.75 ± 2.21 |

| Pre-P(a-et)CO2 (mmHg) | 26.44 ± 4.95 | 24.75 ± 6.15 | 22. 31 ± 7.07 |

| Postlavage | 43.50 ± 15.16 | 42.66 ± 8.67 | 42.88 ± 15.07 |

| 300 minutes | 27.00 ± 2.60 | 30.75 ± 3.06 | 29.06 ± 8.58 |

| Cdyn (mL/cm H2O/kg) | |||

| Prelavage | 0.93 ± 0.16 | 0.98 ± 0.16 | 0.88 ± 0.17 |

| Postlavage | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.06 |

| 300 minutes | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.06 |

| Rawe | |||

| Prelavage | 33.75 ± 3.59 | 45.25 ± 24.06 | 36.75 ± 11.03 |

| Postlavage | 53.50 ± 4.20 | 74.25 ± 25.93 | 59.25 ± 13.07 |

| 300 minutes | 46.75 ± 11.33 | 72.00 ± 22.32 | 55.25 ± 9.85 |

Note: Data are shown as the means ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: VT, tidal volume; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; PaO2, arterial PO2; PAO2, alveolar PO2; PaCO2, arterial PCO2; PetCO2, end-tidal PCO2; P(a-et) CO2, arterial end-tidal PCO2; Rawe, expiratory airway resistance; Cdyn, dynamic respiratory compliance; a/A ratio, arterial/alveolar ratio.

Changes in gas exchange and shunt

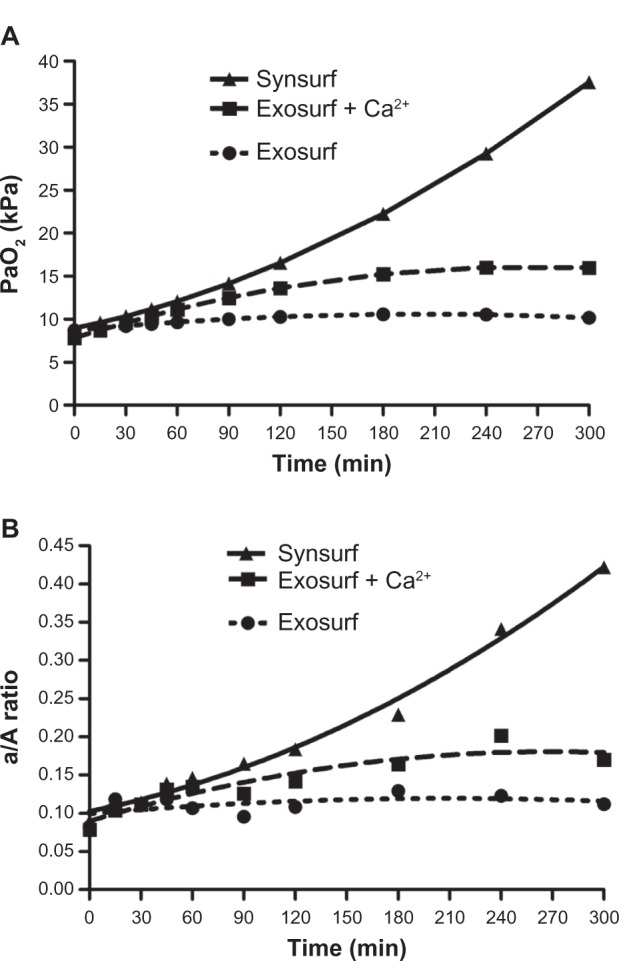

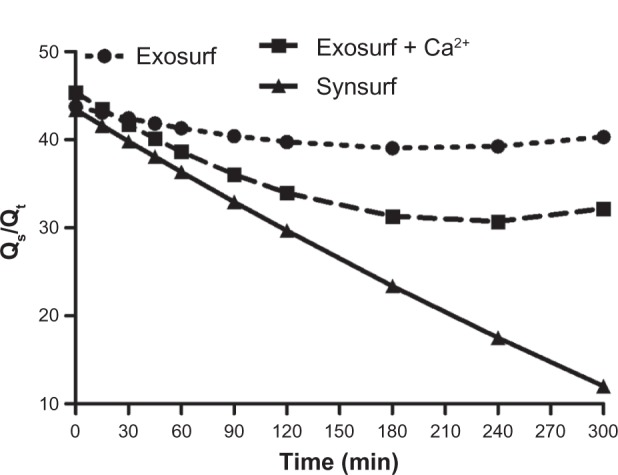

The changes in PaO2 and a/A ratio before and after surfactant treatment are given in Table 1. The PaO2 and a/A ratio decreased significantly (P < 0.05) after lavage. Following treatment with the respective surfactants, the following was noted: oxygenation as reflected by the PaO2 and a/A ratio improved significantly over time in comparison to the postlavage level (time point 0, P < 0.05; Figure 1, A and B). However, significantly better and sustained impovement in systemic oxygenation occurred from baseline at 60 minutes in the animals treated with S (P = 0.02) compared to the other two groups (global test mixed-effects model χ2 = 58.81, P < 0.001). Improvement in oxygenation was also recorded for the animals treated with GECa2+, but it was significantly less than that recorded in the S group. A statistically significant decrease in calculated pulmonary shunt (time period 0–300 minutes) was observed in the S-treated group of animals (intergroup differences S 31.49 ± 10.68 vs GE 41.13 ± 1.63, P = 0.01, and S vs GECa2+ 37.36 ± 5.29, P = 0.002; Friedman analysis of variance). At 300 minutes, the mean calculated value for S was 12.03% versus 32.17% and 40.33% for GECa2+ and GE, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Time profile for oxygenation in the rabbit groups, as reflected by the arterial PaO2 and a/A ratio after surfactant administration.

Abbreviations: a/A, arterial/alveolar; PaO2, arterial PO2.

Figure 2.

Time profile of pulmonary shunt after administration of surfactant in rabbit groups.

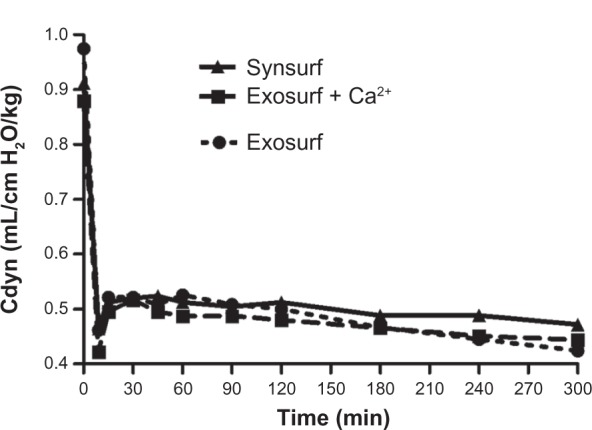

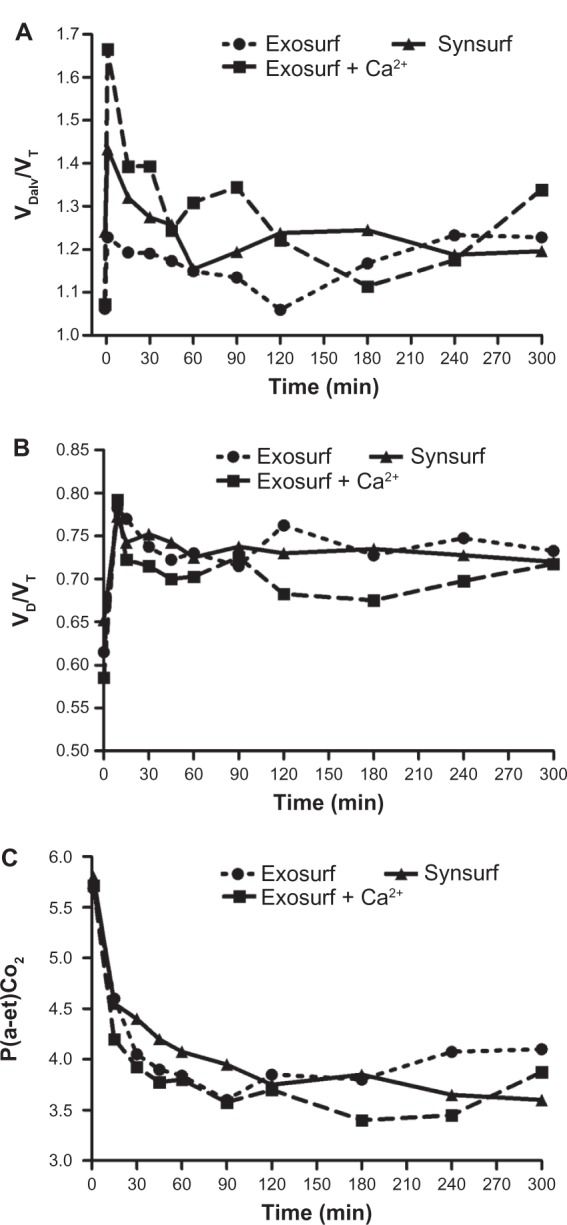

Changes in pulmonary mechanics

Despite the significant improvement in systemic oxygenation (gas exchange), no real changes in pulmonary mechanics from baseline (time point 0) over time were demonstrated. Cdyn decreased significantly from the prelavage value, and in spite of surfactant treatment decreased nonsignificantly thereafter over time in the three groups (Figure 3). BAL resulted in significant reduction of Cdyn in all of the rabbits and an increase of Rawe by approximately 52%, 64% and 61%, respectively, from baseline (Table 1). After surfactant instillation, no significant changes for these two parameters were observed over time. Capnometry revealed the effects of lavage on dead spaces and the changes in VDalv/VT ratio, physiological dead space/VT ratio, VDPhys/VT ratio and the arterial end-tidal PCO2 difference P(a-et)CO2 before lavage and after surfactant treatment (Table 1 and Figure 4A–C). At randomization (baseline), all of these variables had significantly changed in comparison to the prelavage measurements. In all three groups, the VD/VT ratio as well as the VDalv/VT ratio did not change significantly from baseline, despite treatment with surfactant. This finding, together with the increased P(a-et) CO2, indicates a ventilation–perfusion mismatch.

Figure 3.

Compliance of the respiratory system: time-profile comparison of rabbit groups prelavage and after surfactant administration.

Abbreviation: Cdyn, dynamic respiratory compliance.

Figure 4.

Time profile of (A) alveolar dead space/tidal volume ratio (VDalv/VT), (B) dead space/tidal volume ratio (VD/VT), and (C) arterial end-tidal PCO2 difference before and after surfactant administration.

Correlations

We found that the best correlation could be calculated between the physiologic dead space and the a/A PO2 ratio, as well as the physiologic dead space/VT ratio and a/A PO2 ratio in all three groups of rabbits (Table 2). We also found good correlations between the arterial end-tidal PCO2 and VDalv, as well as VDalv/VT components in the S- and GECa2+-treated groups of rabbits (Table 3). There was a significant negative correlation between P(a-et)CO2 and PaO2 in S- and GEca2+-treated rabbits (S, r = −0.65, P = 0.044; GECa2+, r = −0.74, P = 0.014) and a significant positive correlation between P(a-et)CO2 and Qs/Qt in all three groups for shunt percentage above 30% (S, r = 0.86, P = 0.0014; GE, r = 0.92, P = 0.0002; GECa2+, r = 0.91, P = 0.0003).

Table 2.

Relation between arterial/alveolar PO2 ratio and dead-space components

| Surfactant group | Variable | Correlation coefficients

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | r2 | P | ||

| Synsurf | VDalv | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.2704 |

| VDalv/VT | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.3510 | |

| VDphys | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.0000 | |

| VDphys/VT | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.0001 | |

| Exosurf | VDalv | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.0928 |

| VDalv/VT | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.2675 | |

| VDphys | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.0000 | |

| VDphys/VT | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.0000 | |

| Exosurf + Ca2+ | VDalv | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.0497 |

| VDalv/VT | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.0307 | |

| VDphys | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.0006 | |

| VDphys/VT | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.0009 | |

Abbreviations: VDalv, alveolar dead space; VDalv/VT, alveolar dead-space/tidal volume ratio; VDphys, physiologic dead space; VDphys/VT, physiologic dead space/tidal volume ratio.

Table 3.

Relation between arterial end-tidal PCO2 difference and dead-space components

| Surfactant group | Variable | Correlation coefficients

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | r2 | P | ||

| Synsurf | VDalv | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.0004 |

| VDalv/VT | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.0005 | |

| VDphys | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.0382 | |

| VDphys/VT | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.0172 | |

| Exosurf | VDalv | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.0096 |

| VDalv/VT | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.5788 | |

| VDphys | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.1071 | |

| VDphys/VT | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.2861 | |

| Exosurf + Ca2+ | VDalv | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.0002 |

| VDalv/VT | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.00003 | |

| VDphys | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.0091 | |

| VDphys/VT | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.0024 | |

Abbreviations: VDalv, alveolar dead space; VDalv/VT, alveolar dead space/tidal volume ratio; VDphys, physiologic dead space; VDphys/VT, physiologic dead space/tidal volume ratio.

Radiographic changes

Radiographic improvement was found in three out of four animals treated with S, in comparison to one out of four rabbits in the GECa2+ group and two out of four in the pure GE-treated rabbit group.

Discussion and conclusions

By selecting the well-established saline-lavage methodology introduced by Lachmann et al,28 we were able to create acute respiratory failure and lung injury with associated surfactant deficiency in adult rabbits. Repeated saline lavage brought about a deterioration in gas exchange, increased dead spaces, intrapulmonary right-to-left shunting, venous admixture, and impaired lung mechanics.29,32,33

Following lavage, alveoli become unstable and tend to collapse abruptly during expiration when the transalveolar pressure decreases below critical closing pressure.34 In the presence of continuing capillary perfusion of these unstable gas-exchange units, venous admixture (intrapulmonary shunt) increases. Surfactant deficiency induced by BAL elevates alveolar and physiological dead space,25 lowers mean lung volume above residual volume,35 decreases arterial PaO2, increases arterial PaCO2, decreases the a/A ratio, elevates pulmonary arterial pressure,36 elevates systolic right ventricular pressure,23 increases right-to-left shunting/venous admixture,23,25 and increases perfusion of low ventilation– perfusion regions.37 In the adult rabbit, whole-lung lavage increases VDalv almost fivefold and the VDalv/VT ratio from zero to one-third of VT.25 If not treated with surfactant, the majority of lavaged rabbits deteriorate over 1–2 hours in regard to static lung compliance and oxygenation status.38 Like others, we found that lavage increased the alveolar and physiologic dead space/VT ratio.25 The increase in physiological dead space would indicate that less of the tidal volume is involved in gas exchange. In addition we found a good correlation between alveolar and physiological dead space/VT ratio and arterial end-tidal PCO2 differences for the S and GECa+2 groups, but not for the GE group (Table 3). In general, higher arterial end-tidal differences were based on an increase in dead space/VT ratio. The alveolar dead space/VT ratio has previously been shown to be the best indicator of ventilation disorders and to indicate right-to-left shunt, based mainly on atelectasis.25 Regions of high ventilation–perfusion ratios contribute to dead space, and the P(a-A)CO2 value is accepted as an indicator of high ventilation–perfusion lung regions.39 Within 3 hours following surfactant instillation, we found a significant and sustained improvement in oxygenation in S-treated animals compared to the other groups. Concurrent with the improved oxygenation status, we observed a significant decrease in the P(a-et)CO2 in the S and GECa2+ groups, which led us to conclude that S clearly improved (decreased) high ventilation–perfusion regions, more so than was the case in the other two groups.39

An increase in oxygenation following instillation of surfactant is largely due to an increase in lung volume, more specifically the functional residual capacity (FRC),40,41 and it is reasoned that the increase in FRC is due to stabilization of already open but underventilated air spaces and recruitment of atelectatic gas-exchange units. In the presence of surfactant, the relative contribution of these two mechanisms may depend on ventilator settings, ie, employment of PEEP, mean airway pressure, and other recruitment maneuvers. In the present study, PEEP and mean airway pressures did not differ between groups. We did not measure FRC and could not standardize dynamic compliance for changes in FRC. Did we overventilate open lung units? In that regard, we checked and reviewed the quantitative change in compliance during the last 20% of inspiration (C20) and compared this value to the total compliance value for the entire breath (C) using the ratio C20/C.42 In patients with overdistention, the C20/C values decrease below 0.8. Reviewing the same in our groups showed that no rabbits were overventilated for any significant period of time. However, the 300-minute values were significantly lower than the 15-minute values, correlating with higher and lower compliance values at the corresponding time points, respectively. This correlation suggests that some degree of overventilation was taking place that influenced dynamic compliance values towards the end of the study. Another factor that has to be considered in regard to changes observed in oxygenation and shunt over time is lavage-induced pulmonary vascular constriction. In addition to surfactant deficiency, large-volume saline lavage (>20 mL/kg) has previously been shown to increase intrapulmonary right-to-left shunt, with a simultaneous increase in systolic right ventricular pressure.23 We speculate that a raised systolic right ventricular pressure reflects a raised pulmonary vascular resistance, which could have adversely affected cardiac output, with lowered saturation of mixed venous blood. We substituted the true calculation of shunt (which requires measuring of mixed venous blood) with the calculated shunt29 whilst animals were receiving 100% oxygen. Several variables may affect this calculation. In this regard, the effect of FiO2 was taken out of the equation, since FiO2 remained at 1.0. In regard to possible hypoventilation, we measured serial PaCO2 levels and attempted to deliver a constant tidal volume and minute ventilation throughout the study period. Furthermore, PEEP was kept constant, with intermittent checks for inadvertent PEEP, and blood pressure and pulse rates and rectal temperature did not vary between groups. We were able to show that the intrapulmonary right-to-left shunt increased from baseline to approximately 45% after lavage, thereafter significantly decreasing over time following surfactant instillation. The initial postlavage value was very similar to values obtained by Boynton et al35 who determined venous admixture and found that the percentage venous admixture varied between 35% and 55% at a mean airway pressure between 10 and 15 cmH2O, respectively. We therefore conclude that in the S-treated group, mean airway pressure changes possibly altered lung volumes and/or redistributed ventilation within alveoli already ventilated, which affected shunt values.

Since we did not measure pulmonary vascular resistance, mixed venous oxygen content, or assessed lung volume, we speculate that the decrease in shunt fraction after surfactant instillation could be related to one or more of the following: shunting of blood from poorly to better-ventilated lung regions (improved ventilation–perfusion matching), a decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (relief of hypoxic vasoconstriction) in the open but not hypoventilated compartment, or lung-volume recruitment. Similar to our study, Wenzel et al25 found that protein-containing bovine surfactant replacement after BAL improved gas exchange but failed to restore the lung to its prelavage condition, which they concluded indicates that exogenous surfactant affects only partly the recruitment of the atelectatic areas.

A criticism of the present study is the lack of lung histology, and this would have to be addressed in future studies involving animal models treated with newer synthetic surfactants. A paucity of studies in this regard, especially following surfactant treatment after saline lavage of adult rabbits, was noted. Repetitive total lung lavage in adult rabbits leads to a reproducible severe surfactant-deficient lung injury. The most prominent light-microscopy findings include varying degrees of atelectasis, edema, intra-alveolar protein leak, hyaline membrane formation, congestion, patchy intraalveolar hemorrhage, lymphatic dilatation, and infiltration of neutrophils associated with peripheral neutropenia. After treatment with surfactant, these changes are still evident, albeit more marked in placebo controls.12,43,44 In addition, some authors have described better aeration of alveoli, measured by volume density, in surfactant-treated groups.43

Poly-l-lysine can exist in a variety of conformations, depending on the degree of ionization of the amino groups in the side chains, temperature, and salt concentration. When we examined the circular dichroism spectrum of the poly-l-lysine–poly-l-glutamic acid complex, it showed a maxima at 218 nm, indicative that the mixture exists in the native random-coil conformation (JM van Zyl, unpublished results, 2000). This is in accordance with the findings of Chittchang et al45 who found that the random coil is the native secondary structure of polylysine. Although hydrophobicity of poly-l-lysine significantly increases in the order; random coil < α-helix < β-sheet conformers,46 we know from our previous experience that complexes of poly-l-lysine and poly-l-glutamic acid have a degree of hydrophobicity, as we have shown that conjugates of polylysine electrostatically bind to DNA and make good cell-transfecting agents.47 Moreover, poly-l-lysine adopts a β-sheet conformation from the random coil during interaction with phospholipids.48 On the other hand, the random coil (disordered state) of a polymer mixture will favor the exposure of the basic charged surface groups on the lysine side chains whereby the peptide could interact flexibly with other molecules to perform a functional role in cell membranes. The overall effect could then possibly be electrostatic binding to phospholipid monolayers.49 With regards to SP-B, the α-helical and β-sheet secondary structure is proposed to penetrate into the lipid acyl chains of the phospholipid membrane lining in alveolar walls, thus providing stability and preventing atelectatic collapse.50 We therefore make the assumption that the charged amino groups of poly-l-lysine in our S preparation could also possibly interact with the phospholipid bilayer and thus could mimic some structural and/or functional properties of SP-B. On the other hand, as positive charges are important for maintaining the structure and function of SP-C,51 it can alternatively be argued that the overall positive character of poly-l-lysine residues in S could then rather contribute to the mimicking of SP-C structural and/or functional properties.

To conclude, in keeping with the finding of similar experimental and human studies, the best indicator of the efficacy of the surfactant was the changes observed in systemic oxygenation over time. In addition to this, the statistically significant decrease in pulmonary shunt found for the S-treated group of animals suggests that the present phospholipid mixture formulated with poly-l-lysine–poly-l-glutamic acid as a complex (cationic and hydrophobic) improves oxygenation in the rabbit model of acute lung injury/surfactant depletion.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Johan Smith, Johann van Zyl and Arthur Hawtrey are code-signers and developers of the peptide-containing synthetic surfactant. The surfactant has been patented by InnovUS (Stellenbosch University).

References

- 1.Soll R. Natural surfactant extract versus synthetic surfactant for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2:CD000144. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliday HL, Speer CP. Strategies for surfactant therapy in established neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. In: Taeusch HW, editor. Surfactant Therapy for Lung Disease (Lung Biology in Health and Disease) New York: Marcell Dekker; 1995. pp. 443–459. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King RJ, Klass DJ, Gikas EG, Clements JA. Isolation of apoproteins from canine surface active material. Am J Physiol. 1973;224(4):788–795. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffrey A, Whitsett MD, Weaver TE. Hydrophobic surfactant proteins in lung function and disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(26):2141–2148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack MD. Molecular biology of surfactant apoprotreins. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;16(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baatz JE, Bruno MD, Ciraolo PJ, et al. Utilization of modified surfactant-associated protein B for delivery of DNA to airway cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(7):2547–2551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strayer DS, Robertson B. Surfactant as an immunogen: implications for therapy of respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1992;81(5):446–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cochrane CG, Revak SD, Merrit TA, et al. The efficacy and safety of KL4-surfactant in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(1):404–410. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma J, Koppenol S, Yu II, Zografi G. Effects of a cationic and hydrophobic peptide, KL4, on model surfactant lipid monolayers. Biophys J. 1998;74(4):899–907. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77899-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revak SD, Merritt TA, Cochrane CG, et al. Efficacy of synthetic peptide-containing surfactant in the treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infant rhesus monkeys. Pediatr Res. 1996;39(4 Pt 1):715–724. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199604000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durand DJ, Clyman RI, Heymann MA, et al. Effects of a protein-free, synthetic surfactant on survival and pulmonary function in preterm lambs. J Pediatr. 1985;107(5):775–780. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith J, Hoal EG, Coetzee AR, et al. Addition of trehalose to dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine, hexadecanol and tyloxapol improves oxygenation in surfactant-deficient rabbits. S Afr J Sci. 2006;102(3–4):155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith J. Evaluation of a Novel Surfactant (1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-Phosphatidylcholine and Trehalose [C12H22O11]) and Comparison with Other Synthetic Formulations [thesis] Cape Town: Stellenbosch University; 2002. A comparison of Synthetic Surfactants. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notter RH, Finkelstein JN, Taubold RD. Comparative adsorption of natural lung surfactant, extracted phospholipids, and artificial phospholipid mixtures to the air-water interface. Chem Phys Lipids. 1983;33(1):67–80. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(83)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee R, Bellare J. Effect of calcium on the surface properties of phospholipid monolayers with respect to surfactant formulations in respiratory distress syndrome. Biomed Mater Eng. 2001;11(1):43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benson BJ, Williams MC, Sueishi K, Goerke J, Sargeant T. Role of calcium in the structure and function of pulmonary surfactant. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;793(1):18–27. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(84)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Touchstone JC, Chen JC, Beaver KM. Improved separation of phospholipids in thin layer chromatography. Lipids. 1979;15(1):61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath JC, MacKenzie JE, Millar RA. Circulatory responses to ketamine: dependence on respiratory pattern and background anaesthesia in the rabbit. Br J Anaesth. 1975;47(11):1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/bja/47.11.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozma C, Macklin W, Cummins LM, Mauer R. The anatomy, physiology and biochemistry of the rabbit. In: Weisbroth SH, Flatt RE, Kraus AL, editors. The Biology of the Laboratory Rabbit. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rider ED, Ikegami M, Whitsett JA, Hull W, Absolom D, Jobe AH. Treatment responses to surfactants containing natural surfactant proteins in preterm rabbits. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(3):669–676. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dizon-Co L, Ikegami M, Ueda T, et al. In vivo function of surfactants containing phosphatidylcholine analogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(10):918–923. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu GFA, Sun B, Niu SF, Cai YY, Lin K, Lindwall R. Combined surfactant therapy and inhaled nitric oxide in rabbits with oleic acid-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(2):437–443. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9711107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krause MF, Lienhart HG, Haberstroh J, Hoehn T, Schulte-Monting J, Leititis JU. Effect of inhaled nitric oxide on intrapulmonary right-to-left-shunting in two rabbit models of saline lavage induced surfactant deficiency and meconium instillation. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(5):410–415. doi: 10.1007/s004310050841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimensberger PC, Cox PN, Frndova H, Bryan AC. The open lung during small tidal volume ventilation: concepts of recruitment and “optimal” positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(9):1946–1952. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenzel U, Rudiger M, Wagner H, Wauer RR. Utility of deadspace and capnometry measurements in determination of surfactant efficacy in surfactant depleted lungs. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(5):946–953. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199905000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr CL, Ito Y, Manwell SEE, et al. Effects of surfactant distribution and ventilation strategies on efficacy of exogenous surfactant. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85(2):676–684. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.2.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gommers D, Hartog A, van ′t Veen A, Lachmann B. Improved oxygenation by nitric oxide is enhanced by prior lung reaeration with surfactant, rather than positive end-expiratory pressure, in lung-lavaged rabbits. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(11):1868–1873. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199711000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lachmann B, Robertson B, Vogel J. In vivo lung lavage as an experimental model of respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Anaesth Scand. 1980;24(3):231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1980.tb01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coetzee AR. Hipoksie: die agtergrond vir die interpretasie van moontlike oorsake. [Hypoxia: the background to the interpretation of possible causes] S Afr J Crit Care. 1987;3(2):28–31. Afrikaans. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar DR. The R Development Core Team nlme. Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. 2011. R package version 3.1–102.

- 31.Maritz JS, Lombard CJ, Morell CH. Exact group comparison using irregular longitudinal data. Appl Stat. 1998;47(3):351–360. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi T, Kataoka H, Ueda T, Murakami S, Takada Y, Kobubo M. Effects of surfactant supplement and end-expiratory pressure in lung-lavaged rabbits. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57(4):995–1001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.4.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mcculloch PR, Forkert PG, Froese AB. Lung volume maintenance prevents lung injury during high frequency oscillatory ventilation in surfactant-deficient rabbits. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137(5):1185–1192. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.5.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cotton RB. A model of the effect of surfactant treatment on gas exchange in hyaline membrane disease. Semin Perinatol. 1994;18(1):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boynton BR, Villanueva D, Hammond MD, Vreeland PN, Buckley B, Frantz ID. Effect of mean airway pressure on gas exchange during high-frequency oscillatory ventilation. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70(2):701–707. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.2.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burger R, Bryan AC. Pulmonary hypertension after postlavage lung injury in rabbits: possible role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71(5):1990–1995. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.5.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schermuly RT, Gunther A, Weissmann N, et al. Differential impact of ultrasonically nebulized versus tracheal-instilled surfactant on ventilation-perfusion (VA/Q) mismatch in a model of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):152–159. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9812017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makhoul IR, Kugelman A, Garg M, Berkeland JE, Lew CD, Bui K. Intratracheal pulmonary ventilation versus conventional mechanical ventilation in a rabbit model of surfactant deficiency. Pediatr Res. 1995;38(6):878–885. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Billman D, Nicks J, Schumacher R. Exosurf rescue surfactant improves high ventilation-perfusion mismatch in respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1994;18(5):279–283. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950180503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gommers D, Vilstrup C, Bos JAH, et al. Exogenous surfactant therapy increases static lung compliance, and cannot be assessed by measurements of dynamic compliance alone. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(4):567–574. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199304000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cotton RB, Olsson T, Law AB, et al. The physiological effects of surfactant treatment on gas exchange in newborn premature infants with hyaline membrane disease. Pediatr Res. 1993;34(4):495–501. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199310000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher JB, Mammel MC, Coleman JM, Bing DR, Boros SJ. Identifying lung overdistention during mechanical ventilation by using volume-pressure loops. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1988;5(1):10–14. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou BH, Sun B, Zhou ZH, Zhu LW, Fan SZ, Lindwall R. Comparison of effects of surfactant and inhaled nitric oxide in rabbits with surfactant-depleted respiratory failure. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1999;20(8):691–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burger R, Fung D, Bryan ACJ. Lung injury in a surfactant-deficient lung is modified by indomethacin. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69(6):2067–2071. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.6.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chittchang M, Alur HH, Mitra AK, Johnston TP. Poly(L-lysine) as a model drug macromolecule with which to investigate secondary structure and membrane transport, part 1: physicochemical and stability studies. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001;54(3):315–323. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gray RA, Vander Velde DG, Burke CJ, Manning MC, Middaugh CR, Borchardt RT. Delta-sleep-inducing peptide: solution conformational studies of a membrane-permeable peptide. Biochemistry. 1994;33(6):1323–1331. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larson G, Pieterse A, Quick G, Van der Bijl P, Van Zyl J, Hawtrey A. Development of a reproducible procedure for plasmid DNA encapsulation by red blood cell ghosts. Biodrugs. 2004;18(3):189–198. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200418030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fukushima K, Sakamoto T, Tsuji J, Kondo K, Shimozawa R. The transition of α-helix to β-structure of poly(L-lysine) induced by phosphatidic acid vesicles and its kinetics at alkaline pH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1191(1):133–140. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carrier D, Dufourcq J, Faucon JF, Pézolet M. A fluorescence investigation of effects of polylysine on dipalmitoylphosphatidylglycerol bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;820(1):131–139. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitsett JA, Weaver TE. Hydrophobic surfactant proteins in lung function and disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(26):2141–2148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Creuwels LAJM, Boer EH, Demel RA, Van Golde LMG, Haagsman HP. Neutralization of the positive charge of SP-C: effects in structure and function. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(27):16225–16229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]