Abstract

Human cystic echinococcosis (hydatid disease) caused by the Echinococcus granulosus tapeworm continues to be a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality in many parts of the world. France is still considered as endemic area, but the current infestation by E. granulosus of intermediate hosts in France remains currently unknown due to the absence of official data reporting for the last 20 years. A 1-year prevalence survey was conducted in the 24 slaughterhouses of ten departments of the South of France. We demonstrate that the E. granulosus parasite is still currently present at low prevalence at slaughterhouses in the study area (4 cases for 100,000 sheep and 3 cases for 100,000 cattle). In addition, we assess the presence of genotype G1 in infected animals and identify for the first time in France genotypes G2 and G3 of E. granulosus sensu stricto.

Hydatid disease is a parasitic zoonosis caused by the Echinococcus granulosus tapeworm, which continues to be a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality in many parts of the world (Craig et al. 2007). Human is considered as a dead-end host in the parasite life cycle. Dog is the main definitive host of the cestode and release eggs in its faecal matter infesting the environment. Usual intermediate hosts are sheep, cattle, swine and goats but horses, cervids or camels can also present visceral cysts. Molecular analyses of mtDNA sequences have previously demonstrated that E. granulosus can be divided into ten different genotypes, named G1 to G10 (Bowles et al. 1992; Bowles and McManus 1993; Lavikainen et al. 2003; Scott et al. 1997) corresponding to the previous strains definitions (Thompson 1995) The taxonomy of E. granulosus was recently revised leading to a more simplified one by grouping some genotypes in order to obtain new valid species: E. granulosus sensu stricto (G1,G2,G3), Echinococcus equinus (G4), Echinococcus ortleppi (G5) and Echinococcus canadensis (G6 to G10)(Nakao et al. 2007, 2010; Thompson and McManus 2002).

The last national survey on E. granulosus in France dates back to 1989 (Soule et al. 1989). Diagnosis was based on the macroscopic observation of hydatid cysts at the slaughterhouse. National infection prevalence was 0.42 % in sheep or goats (n = 515,679) and 0.13 % in cattle (n = 2,876,863). If almost all the country was observed infected, the main infected area was the south of France, where sheep breeding and traditional transhumance is concentrated. More recently, a regional survey on 43,148 cattle in the Midi-Pyrenees region revealed a prevalence at slaughterhouse of 0.31 % (Bichet and Dorchies 1998). Since 1998, no data were available. Moreover, no case has been officially declared by slaughterhouses because of no reporting obligation concerning E. granulosus, explaining why no case is yearly reported by French agriculture authority to the European Food Safety Agency. Yet, France is commonly considered as endemic (Eckert et al. 2001), whereas human cases of hydatidosis identified in France are most often considered as imported cases (i.e. infestation of the patient outside France).

The aim of the present study was thus to conduct a survey in slaughterhouses of the south of France, the main historic endemic area of E. granulosus (Romig et al. 2006), to assess the presence and the prevalence of the parasite in sheep and cattle and to identify the species/genotypes of E. granulosus sensu lato.

From April 2009 to March 2010, 725,903 sheep and 138,624 cattle were inspected in the 24 slaughterhouses of ten departments (French administrative unit) of the south of France. During meat inspection (visual examination and palpation), any hydatid cyst found on the liver or lungs of inspected cattle and sheep was collected. The samples were kept in ethanol (70 %) or frozen prior to be dispatched to the National Reference Laboratory for Echinococcus sp. (NRL).

At the NRL, hydatid fluid of each sample, if any, was microscopically observed for the presence of protoscoleces in order to assess the fertility of the cyst. Protoscoleces or germinal layers were collected from hydatid cysts and kept frozen prior to molecular analysis. DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, France) according to the supplier’s recommendations.

For all DNA extracts, PCR were conducted on the gene encoding subunit 1 of the cytochrome c oxidase (cox1) and for the gene encoding subunit 1 of NADH dehydrogenase (nad1). The cox1 sequence was amplified using primers JB3-JB4.5 (Bowles et al. 1992) and nad1 with primers JB11-JB12 (Bowles and McManus 1993). PCR were carried out under the following conditions: 2 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 30 s at 52 °C for cox1 and at 54 °C for nad1, 72 °C for 30 s and a final elongation stage at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were visualised after electrophoresis using a 1 % w/v agarose gel stained with SYBR® Safe (Invitrogen, France). The amplicons were sequenced by a private company (Beckmann Coulter Genomics, UK). The nucleotide sequences were aligned using the Vector NTI software program (Invitrogen, France) and compared with sequences available in GenBank using the BLASTn program. The E. granulosus genotypes were determined using the reference sequences available of the cox1 and nad1 genes (Bowles et al. 1992; Bowles and McManus 1993; Okamoto et al. 1995).

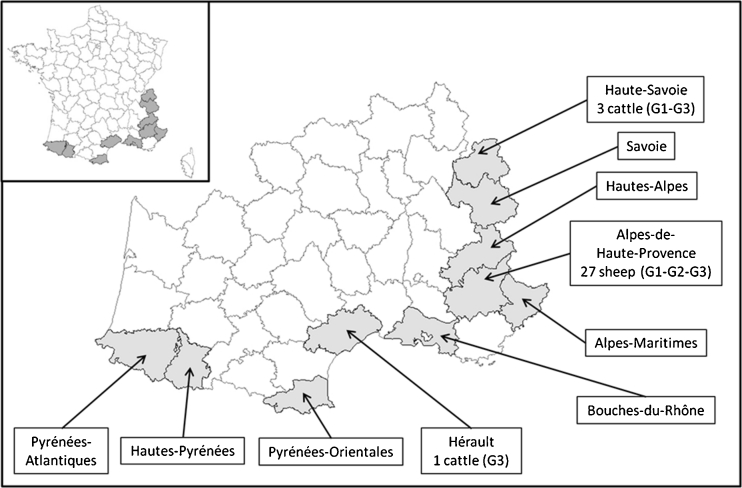

Hydatid cysts from 31 animals coming from three of the ten departments surveyed: 27 sheep from Alpes-de-Haute-Provence and four cattle from Haute-Savoie (n = 3) and Hérault (n = 1) (Fig. 1). Analyses of the nucleotide sequences of the cox1 and nad1 genes confirmed the E. granulosus species for all the samples (Table 1). These results indicate an apparent prevalence of hydatidosis in livestock of the whole study area of 4 cases for 100,000 animals: 4 cases for 100,000 in sheep and 3 cases for 100,000 in cattle. In fact, as the infection concerned only animals from three departments of slaughtering, the prevalence is locally higher: 6 cases for 1000,000 sheep in Alpes-de-Haute-Provence and 13 and 25 cases for 100,000 cattle in Haute-Savoie and Hérault, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Origin of the hydatid cysts samples. In grey are the department surveyed. The numbers of cattle or sheep indicate the number and breeding species of infected animals by E. granulosus in each department

Table 1.

Number of inspected cattle and sheep, E. granulosus cases, and apparent prevalence per department

| Department of slaughtering | Animals inspected | E. granulosus s.s. genotypes | Apparent prevalence at slaughterhouse (cases for 100,000) [IC95 %] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | Sheep | G1 | G2 | G3 | G1/G2 | G1/G3 | Overall | Cattle | Sheep | |

| Pyrenees-Orientales | 3,522 | 37,347 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hautes-Pyrenees | 10,943 | 27,485 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Savoie | 14,028 | 7,426 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Haute-Savoie | 23,8 | 0 | 2a | – | 1a | – | – | – | 13a [4–37] | – |

| Bouches-du-Rhone | 5,556 | 39,395 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pyrenees-Atlantiques | 72,397 | 105,664 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Herault | 4,016 | 26,945 | – | – | 1a | – | – | 1a | 25a [4–141] | – |

| Hautes-Alpes | 3,947 | 16,636 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alpes-Maritemis | 415 | 5,182 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alpes-de-Haute-Provence | 0 | 459,923 | 8b | 10b | 6b | 2b | 1b | 27b | – | 6b [4–9] |

| Whole study area | 138,624 | 725,903 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 31 (4a + 27b) | 3a [1–7] | 4b [3–5] |

| 4 [2–5] | ||||||||||

(–) no case

aCattle

bSheep

Single genotypes G1, G2 and G3 of E. granulosus sentu stricto (s.s.) were identified for ten, ten and eight animals, respectively. Moreover, three sheep exhibited mixed genotyping patterns G1/G2 (n = 2) and G1/G3 (n = 1), due to different genotypes obtained for cysts in the liver and lungs. For the G1 genotype, the nucleotide sequence of the cox1 gene obtained (GenBank JQ356712) corresponded to the reference sequence (GenBank U50464), except for one ovine which presented a unique substitution of a thymine by a cytosine in the 67th nucleotide position (GenBank JQ356711). The nucleotide sequences identified as G2 and G3 from sheep (GenBank JQ356713, JQ356715) and cattle (GenBank JQ356714), respectively, corresponded to the appropriate reference sequences of cox1 gene (GenBank M84662 and M84663). Concerning the nad1 gene, the sequences obtained from sheep (GenBank JQ356721, JQ356723) and cattle (GenBank JQ356720, JQ356722) were all identical to G1 and G2-G3 reference sequences (GenBank AJ237633, AJ237634). Among the 27 positive sheep, all slaughtered in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department, 70 % of the hydatid cysts were found on both liver and lungs, 15 % on solely the liver and 15 % on solely the lungs. For cattle, the parasitic infection was observed on the lungs in three cases and on the liver for one cow. Protoscoleces were observed in 81 % of the sheep cysts (n = 23), independently of the genotype and organs involved, whereas no protoscolex were observed for all the four cattle.

Whereas no official data of E. granulosus infection are reported in France nowadays, because of no reporting obligation, we show here that E. granulosus is still spread at least in the main endemic region of mainland France, i.e., the Pyrenean and Alpine departments bordering other endemic countries, Spain (González et al. 2002) and Italy (Casulli et al. 2008; Rinaldi et al. 2008), respectively. The current level of infection is much lower than in 1989, both in cattle and in sheep. Moreover, while the presence of cases in sheep in the south-east is confirmed, no case was observed in the south-west, particularly in Pyrénées-Atlantiques, which was a major area of sheep infection in 1989. A broader survey covering the whole country would enable to determine if the location of E. granulosus is limited to the studied area or not.

The genotype G1 of E. granulosus s.s. is the most widespread genotype in southern Europe (Romig et al. 2006), and its presence in France is commonly admitted even if no published data for G1 are available. Here, we actually assess its presence. We also described for the first time in France the genotypes G2 and G3 of E. granulosus s.s. These two genotypes have already been described in Europe in sheep and cattle, notably in Italy (Busi et al. 2007; Casulli et al. 2008), Romania (Bart et al. 2006), Portugal (Beato et al. 2010) and Turkey (Vural et al. 2008). The genotype G1 is mainly responsible for infection in humans, but genotypes G2 and G3 are known to be infectious as well (Busi et al. 2007; Eckert and Thompson 1997; Maillard et al. 2007).

Mixed genotyping patterns in sheep were identified, due to infection of liver and lungs by two distinct genotypes of E. granulosus. At least one of the two genotypes identified in these mixed genotyping pattern was systematically observed in other sheep within the three different herds concerned (data not shown). These mixed profiles can be explained by successive infections of the intermediate hosts, or by a single infection due to a definitive host harbouring simultaneously adult worms of the two genotypes. Moreover, 85 % of the sheep cysts were fertile. These results reveal the coexistence of active G1, G2 and G3 parasitic life cycles in some department. The department of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence is a crossroad of the sheep transhumance in the Alps which is probably the main factor to explain the transmission of the parasite in sheep.

None of the infected cattle exhibited fertile cyst. This result is in agreement with those obtained in Italy (Rinaldi et al. 2008) and in Spain (Mwambete et al. 2004), indicating that, except for infection by their attributed genotype/species (G5, E. ortleppi) (Thompson 1986), cattle are not a major active intermediate hosts for E. granulosus s.s. but a dead-end host. Nevertheless, the infection of the four cattle observed in the department of Hérault and Haute-Savoie indicates that they are bred in, or have transited by, infested areas where active life cycles of E. granulosus s.s. persist.

The persistence of E. granulosus life cycle depends on the ability for dogs, the definitive hosts, to consume infested organs of intermediate host. When livestock are slaughtered in an official slaughterhouse, these infested organs are seized and destroyed. The presence of E. granulosus in France highlight in the present study can be explained by different hypotheses. One can be that some uncontrolled slaughter without elimination of all infested organs still occurs. Secondly, dogs infected by the parasite may be imported from endemic areas which results to contamination of the pastures. Finally, the death of animals without collection and treatment of carcass can appear for instance in mountain pasture. The study of the infection in sheep dogs would enable to assess the persistence of E. granulosus s.s. in France at a more accurate geographical level.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the departmental veterinary authorities for samples collection in slaughterhouses.

References

- Bart JM, Moriaru S, Knapp J, Ilie MS, Pitulescu M, Anghel A, Cosoroaba I, Piarroux R. Genetic typing of Echinococcus granulosus in Romania. Parasitol Res. 2006;98(2):130–137. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato S, Parreira R, Calado M, Grácio MAA. Apparent dominance of the G1-G3 genetic cluster of Echinococcus granulosus strains in the central inland region of Portugal. Parasitol Int. 2010;59(4):638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet H, Dorchies P. Estimation of the prevalence of bovine hydatid cyst in the south Pyrenees. Parasite. 1998;5(1):61–68. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1998051061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, McManus DP. NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene sequences compared for species and strains of the genus Echinococcus. Int J Parasitol. 1993;23(7):969–972. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(93)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Blair D, McManus DP. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90109-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busi M, Šnábel V, Varcasia A, Garippa G, Perrone V, De Liberato C, D’Amelio S. Genetic variation within and between G1 and G3 genotypes of Echinococcus granulosus in Italy revealed by multilocus DNA sequencing. Vet Parasitol. 2007;150(1–2):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casulli A, Manfredi MT, La Rosa G, Cerbo AR, Genchi C, Pozio E. Echinococcus ortleppi and E. granulosus G1, G2 and G3 genotypes in Italian bovines. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155(1–2):168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, Chabalgoity JA, Garcia HH, Gavidia CM, Gilman RH, Gonzalez AE, Lorca M, Naquira C, Nieto A, Schantz PM. Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(6):385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert J, Thompson RC. Intraspecific variation of Echinococcus granulosus and related species with emphasis on their infectivity to humans. Acta Trop. 1997;64(1–2):19–34. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(96)00635-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin FX, Pawlowski ZS. WHO/OIE Manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. Paris: O.I.E.–O.M.S; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- González LM, Daniel-Mwambete K, Montero E, Rosenzvit MC, McManus DP, Garate T, Cuesta-Bandera C. Further molecular discrimination of Spanish strains of Echinococcus granulosus. Exp Parasitol. 2002;102(1):46–56. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4894(02)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavikainen A, Lehtinen MJ, Meri T, Hirvela-Koski V, Meri S. Molecular genetic characterization of the Fennoscandian cervid strain, a new genotypic group (G10) of Echinococcus granulosus. Parasitology. 2003;127(Pt 3):207–215. doi: 10.1017/S0031182003003780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard S, Benchikh-Elfegoun MC, Knapp J, Bart JM, Koskei P, Gottstein B, Piarroux R. Taxonomic position and geographical distribution of the common sheep G1 and camel G6 strains of Echinococcus granulosus in three African countries. Parasitol Res. 2007;100(3):495–503. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwambete K, Ponce-Gordo F, Cuesta-Bandera C. Genetic identification and host range of the Spanish strains of Echinococcus granulosus. Acta Trop. 2004;91(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M, McManus DP, Schantz PM, Craig PS, Ito A. A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Parasitology. 2007;134(Pt 5):713–722. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M, et al. State-of-the-art Echinococcus and Taenia: phylogenetic taxonomy of human-pathogenic tapeworms and its application to molecular diagnosis. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10(4):444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Bessho Y, Kamiya M, Kurosawa T, Horii T. Phylogenetic relationships within Taenia taeniaeformis variants and other taeniid cestodes inferred from the nucleotide sequence of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene. Parasitol Res. 1995;81(6):451–458. doi: 10.1007/BF00931785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi L, Maurelli MP, Veneziano V, Capuano F, Perugini AG, Cringoli S. The role of cattle in the epidemiology of Echinococcus granulosus in an endemic area of southern Italy. Parasitol Res. 2008;103(1):175–179. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romig T, Dinkel A, Mackenstedt U. The present situation of echinococcosis in Europe. Parasitol Int. 2006;55(Suppl):S187–S191. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Stefaniak J, Pawlowski ZS, McManus DP. Molecular genetic analysis of human cystic hydatid cases from Poland: identification of a new genotypic group (G9) of Echinococcus granulosus. Parasitology. 1997;114(Pt 1):37–43. doi: 10.1017/S0031182096008062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule C, Fabien JF, Maillot E (1989) Enquête échinococcose-hydatidose. DGAL–CNEVA–LCRV, Nogent-sur Marne–Maisons-Alfort, p. 173

- Thompson RCA. The biology of Echinococcus and hydatid disease. London: Allen & Unwin; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RCA. Biology and systematics of Echinococcus. In: Thompson RCA, Lymbery AJ, editors. Echinococcus and hydatid disease. Wallingford: CAB; 1995. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RC, McManus DP. Towards a taxonomic revision of the genus Echinococcus. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(10):452–457. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vural G, Baca AU, Gauci CG, Bagci O, Gicik Y, Lightowlers MW. Variability in the Echinococcus granulosus cytochrome C oxidase 1 mitochondrial gene sequence from livestock in Turkey and a re-appraisal of the G1-3 genotype cluster. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154(3–4):347–350. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]