Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) is recommended for pregnant women who test positive for group B Streptococcus (GBS) in their genitourinary tract to prevent GBS-induced neonatal sepsis. Penicillin G is used as the primary antibiotic, and clindamycin or erythromycin as the secondary, if allergies exist. Decreased susceptibility to penicillin G has occasionally been reported; however, clindamycin and erythromycin resistance is on the rise and is causing concern over the use of clindamycin and erythromycin IAP.

METHODS:

Antibiotic resistance was characterized phenotypically using a D-Test for erythromycin and clindamycin, while an E-Test (E-strip) was used for penicillin G. GBS was isolated from vaginal-rectal swabs and serologically confirmed using Prolex (Pro-Lab Diagnostics, Canada) streptococcal grouping reagents. Susceptibility testing of isolates was performed according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines.

RESULTS:

All 158 isolates were penicillin G sensitive. Inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance was observed in 13.9% of isolates. Constitutive MLSB resistance was observed in 12.7% of isolates. M phenotype resistance was observed in 6.3% of isolates. In total, erythromycin resistance was present in 32.9% of the GBS isolates, while clindamycin resistance was present in 26.6%.

DISCUSSION:

The sampled GBS population showed no sign of reduced penicillin susceptibility, with all being well under susceptible minimum inhibitory concentration values. These data are congruent with the large body of evidence showing that penicillin G remains the most reliable clinical antibiotic for IAP. Clindamycin and erythromycin resistance was higher than expected, contributing to a growing body of evidence that suggests the re-evaluation of clindamycin and erythromycin IAP is warranted.

Keywords: Clindamycin, Erythromycin, Group B Streptococcus, Macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance, Penicillin resistance, Regional hospital

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La prophylaxie antibiotique intrapartum (PAI) est recommandée chez les femmes enceintes positives au Streptococcus du groupe B (SGB) dans l’appareil génito-urinaire, afin de prévenir la septicémie néonatale induite par le SGB. La pénicilline G est utilisée comme antibiotique primaire et, en cas d’allergies, la clindamycine ou l’érythromycine comme antibiotique secondaire. On déclare parfois une diminution de la susceptibilité à la pénicilline G, mais la résistance à la clindamycine et à l’érythromycine est à la hausse et suscite des inquiétudes quant à leur utilisation en PAI.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont caractérisé les phénotypes de résistance aux antibiotiques au moyen d’un test de diffusion pour l’érythromycine et la clindamycine et d’un test E (bandelette E) pour la pénicilline G. Ils ont isolé le SGB dans les écouvillons vagino-rectaux et en ont fait la confirmation sérologique au moyen des réactifs de groupement streptococcique Prolex (Pro-Lab Diagnostics, Canada). Les tests de susceptibilité des isolats ont été exécutés conformément aux lignes directrices du Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute.

RÉSULTATS :

Les 158 isolats étaient sensibles à la pénicilline G. Les chercheurs ont observé une résistance au macrolide, à la lincosamide et à la streptogramine de type B (MLSB) dans 13,9 % des isolats. Ils ont observé une résistance à MLSB dans 12,7 % des isolats et la résistance au phénotype M dans 6,3 % des isolats. Au total, ils ont constaté une résistance à l’érythromycine dans 32,9 % des isolats de SGB, et une résistance à la clindamycine dans 26,6 % des cas.

EXPOSÉ :

L’échantillon de population atteint du SGB n’a révélé aucun signe de diminution de la susceptibilité à la pénicilline, car tous les sujets se situaient bien en deçà des valeurs CMI susceptibles. Ces données coïncident avec le vaste ensemble de données probantes démontrant que la pénicilline G demeure l’antibiotique clinique le plus fiable pour la PIA. La résistance à la clindamycine et à l’érythromycine était plus élevée que prévu, ce qui contribue à l’ensemble croissant de données probantes indiquant qu’il faut réévaluer la PIA à la clindamycine et à l’érythromycine.

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) are commensal bacteria of the human gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract that are clinically significant due to their role as a major cause of neonatal sepsis and meningitis (1). Neonatal GBS infections occur as early or late onset (2) and, in the early 1990s, before widespread preventative measures were in place, early onset GBS neonatal infections occurred at an overall rate of 1.2 per 1000 live births in Canada (3). The 1994 consensus policy statement by the Canadian Paediatric Society and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) on neonatal GBS disease first recommended an intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) regimen that was shown to be effective in preventing vertical transmission of early onset GBS infections (4). Since 1994, continually updated IAP recommendations that now include universal culture screening have been reducing cases of neonatal GBS infections, as demonstrated by the latest 2004 SOGC guidelines that report infection rates of 0.64 per 1000 live births (5). Even more recent is the 2010 United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC, Georgia, USA) revised guidelines on the prevention of perinatal GBS disease, which reported infection rates of between 0.34 and 0.37 per 1000 live births (6). A recent major concern, however, is the loss of IAP effectiveness due to an increase in antibiotic resistance among the GBS population. Penicillin G is the primary antibiotic used, while clindamycin and erythromycin are secondary and used only when a risk of anaphylaxis from penicillin and cefazolin exists (5,6). GBS has remained universally susceptible to penicillin G; however, some cases of reduced penicillin susceptibility strains have been reported. Consecutive mutations in the penicillin binding proteins were shown to be the cause of the reduced susceptibility (7), which reinforces the need for closely monitoring penicillin G minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). Clindamycin and erythromycin resistance in GBS is well documented, and has been shown recently to be substantially rising in other parts of the world, notably the United States (8,9), demanding continuous monitoring of both resistance rates to ensure an effective IAP regimen is implemented. To our knowledge, no such data have been reported for the Royal Inland Hospital (RIH), which is a regional hospital serving the Thompson, Nicola and Cariboo regions of British Columbia.

METHODS

One hundred fifty-eight GBS isolates were collected between September 2010 and March 2011 from 158 vaginal-rectal swabs of pregnant patients. Each swab was subsequently used to inoculate LIM broth (Oxoid, ThermoFisher, United Kingdom), which was then incubated overnight. Broth (50 μL) was plated onto a chromagar plate (GBSelect, Bio-Rad, USA) and incubated overnight. Turquoise-coloured colonies were tested using Prolex (Pro-Lab Diagnostics, Canada) extraction and streptococcal grouping reagents (Intermedico, Canada) to positively identify GBS. The GBS isolates to be included in the study were plated on 5% blood agar plates and briefly kept under 4°C refrigeration until they were subcultured and subsequently screened for penicillin G and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance using an E-Test and D-Test, respectively, on 5% blood agar plates. For the E-Test, the MICs were read directly off a penicillin G epsilometer in μg/mL. The D-Test is a disc diffusion test performed by using 2 μg clindamycin disk adjacent (seperated by 12 mm) to a 15 μg erythromycin disc, which measures the zones of inhibition in millimeters. The D-test has the ability to phenotypically identify inducible, constitutive or M phenotype MLSB resistance. The tests were performed with strict adherence to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines for β-hemolytic Streptococci antimicrobial testing (10). Four strains of Staphylcoccus aureus, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 29213, ATCC 25923, ATCC BAA 977 and ATCC BAA 976 (Lyphocult, BioMerieux, France) were used to ensure the quality and accuracy of susceptibility measurements, as per CLSI guidelines.

RESULTS

Penicillin G susceptibility testing of the 158 GBS isolates revealed that no isolates were resistant, with all MIC levels well below the CLSI sensitivity limit of 0.12 μg/mL (Table 1). The highest observed MIC value was 0.064 μg/mL, which was seen in 41% of isolates. The second highest MIC value of 0.047 μg/mL was observed in 56% of isolates and, finally, the lowest MIC value of 0.032 μg/mL was observed in 3% of isolates. These data confirm predictions of a stable penicillin G-sensitive GBS population at the RIH. Table 2 summarizes the results observed from using the D-test to evaluate erythromycin and clindamycin resistance levels, which show four possible phenotypic observations. The first was inducible resistance, characterized by erythromycin inducing resistance to clindamycin. The second was constitutive resistance, characterized by resistance to both erythromycin and clindamycin. The third was M phenotype resistance, characterized by resistance to erythromycin but susceptibility to clindamycin. The fourth was susceptibility to both antibiotics. Only 67.1% of tested isolates showed sensitivity to both erythromycin and clindamycin. Constitutive resistance was observed in 12.7% of isolates, 13.9% had inducible clindamycin resistance and, finally 6.3% had M phenotype resistance. In a clinical setting, inducible clindamycin resistance is considered to be resistant, therefore; a total of 26.6% of the tested isolates were clindamycin resistant. The total prevalence of erythromycin resistance was 32.9%.

TABLE 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)* values observed according to a penicillin G susceptibility test (E-test)

| MIC, μg/mL | % Isolates |

|---|---|

| 0.064 | 41 |

| 0.047 | 56 |

| 0.032 | 3 |

For each isolate, a penicillin G epsilometer in μg/mL was used to screen for penicillin G resistance/susceptibility and the MIC value was measured.

The sensitivity limit of the MIC according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute is 0.12 μg/mL

TABLE 2.

Erythromycin and clindamycin resistance phenotypes (D-Test)*

| Resistance phenotype | Isolates, n | % Isolates |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible MLSB† | 22 | 13.9 |

| Constitutive MLSB‡ | 20 | 12.7 |

| M phenotype§ | 10 | 6.3 |

| No resistance¶ | 106 | 67.1 |

| Total | 158 | 100 |

The D-Test is a disc diffusion test, which uses a 2 μg clindamycin disk adjacent (seperated by 12 mm) to a 15 μg erythromycin disc, which measures the zones of inhibition in millimeters. The D-test has the ability to phenotypically identify inducible, constitutive, or M phenotype macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance and no resistance;

Inducible MLSB resistance is characterized by erythromycin inducing resistance to clindamycin;

Constitutive MLSB resistance is characterized by resistance to both erythromycin and clindamycin;

M phenotype MLSB resistance is characterized by resistance to erythromycin but susceptibility to clindamycin.

No resistance is characterized by susceptibility to both antibiotics

DISCUSSION

Since the introduction of IAP in the early 1990s, the possibility of an increase in antibiotic resistance has been a concern. Even after an extensive implementation of penicillin G as the primary antibiotic for GBS IAP, the literature has reported a relatively stable susceptibility rate (6,8). Our data contribute to this view, with the highest MIC observed being only 0.064 μg/mL, which is low relative to the CLSI susceptibility limit of 0.12 μg/mL (10). However, it must be remembered that MIC rates as high as 1.0 μg/mL have now been reported (7) and, therefore, the medical community should remain diligent in monitoring penicillin susceptibility.

Resistance rates for the secondary antibiotics clindamycin and erythromycin are also important, considering that in Canada 10% of patients will self-report an allergy to penicillin (11). The CDC reported erythromycin resistance rates of up to 32% in the United States from 2006 to 2009, and the 2010 CDC guidelines no longer recommend erythromycin as an acceptable antibiotic for IAP (6). We have reported an erythromycin resistance rate of 32.9%, suggesting that there is a potential need to review the Canadian guidelines to reconsider the continued use of erythromycin for IAP.

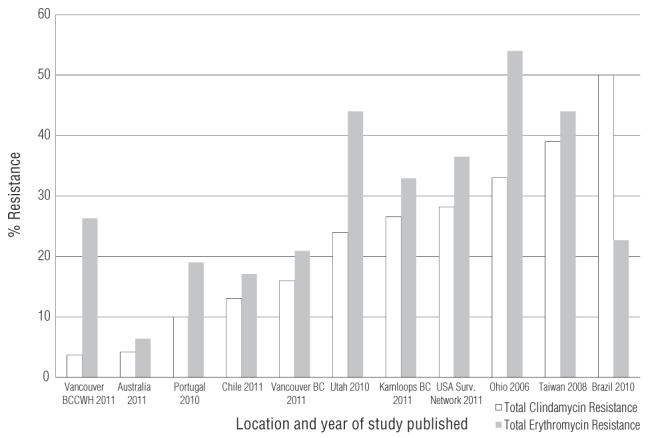

With regard to clindamycin resistance, as of 2004, the SOGC reported rates as high as 15% (5), while the CDC reported rates as high as 20% from 2006 to 2009 (6). Our clindamycin resistances rates are higher (26.6%). Recent Canadian studies on GBS resistance rates are lacking; however, our study reports much higher clindamycin rates than a study from Vancouver, British Columbia (12), which reported rates of 3.7% and 16% from an outpatient laboratory and hospital laboratory, respectively. Geographical variations in resistance rates may be caused by environmental factors such as regional use of clindamycin. International GBS clindamycin resistance rates also reveal wide geographical variation in recent studies, with low rates of 4.2% in Australia, all the way up to high rates of 50% in Brazil, including many in between (13–17) (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Comparison of recently published studies on rates of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance observed worldwide. BCCWH British Columbia Children’s and Women’s Hospital

Studies conducted in the United States have recently reported large increases in rates of clindamycin resistance among GBS. A new study from upstate New York reported 38.4% resistance to clindamycin and 50.7% resistance to erythromycin (9). Other recent studies from across the United States have reported clindamycin resistance rates of 24%, 28.2% and 33% (18,19). We found a clindamycin resistance rate of 26.6% at RIH, which may reflect a North American trend of increasing resistance. More Canadian studies are required to confirm our findings.

It is evident that before clindamycin is used in instances of penicillin allergy, susceptibility testing is essential to ensure an effective IAP regimen is implemented. Therefore, clinical microbiology laboratories should routinely test and report clindamycin and erythromycin susceptibilities of GBS isolated from vaginal-rectal swabs of pregnant women. Clinicians should not prescribe erythromycin or clindamycin empirically for IAP.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Biological Sciences and Faculty of Science at Thompson Rivers University (TRU) (Kamloops, British Columbia) for their continued support. Their sincere thanks go to Dr Colin James of the TRU AVP Research & Graduate Studies Office for his manuscript editorial skill. Special thanks to Carolynne Fardy for her laboratory assistance and all unnamed staff at the Royal Inland Hospital (Kamloops) microbiology laboratory for collecting and characterizing all the isolates for the present study. The present work was selected and poster-presented in student sessions at both the 2011 Annual Conference of the Canadian Society of Microbiologists and the General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. Thanks also go to the TRU Comprehensive Undergraduate Enhancement Fund Travel Fund for travel expenses to present this work at the 111th American Society for Microbiology General Meeting in New Orleans (USA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Schrag S, Zywicki S, Farley M, et al. Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:15–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001063420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franciosi RA, Knostman JD, Zimmerman RA. Group B streptococcal neonatal and infant infections. J Pediatr. 1973;82:707–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies HD, Leblanc J, Bortolussi R, McGeer A, PICNIC The Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada (PICNIC) study of neonatal group B streptococcal infections in Canada. Pediatr Child Health. 1999;4:257–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and Canadian Paediatric Society National consensus statement on the prevention of early onset group B streptococcal infections in the newborn. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 1994;16:2271–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada Infectious Diseases Committee The prevention of early onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26:826–32. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: Revised guidelines from the CDC. MMWR. 2010;59:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura K, Suzuki S, Wachino J, et al. First molecular characterization of group B streptococci with reduced penicillin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2890–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00185-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards M. Issues of antimicrobial resistance in group B Streptococcus in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2006;17:149–52. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Back EE, O’Grady E J, Back JD. High rates of perinatal Group B Streptococcus clindamycin and erythromycin resistance in an Upstate New York hospital. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 56(2) doi: 10.1128/AAC.05794-11. < http://aac.asm.org/content/early/2011/12/01/AAC.05794-11.abstract> (Accessed January 16, 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twentieth Informational Supplement M100-S20 January. 2010;30:M100–S20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada Infectious Diseases Committee Antibiotic prophylaxis in obstetric procedures. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:878–92. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34662-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong T, Dhaliwal S, Al-rawahi G, et al. Community and hospital antibiotic profiles of group B Streptococcus for penicillin, erythromycin and clindamycin in Vancouver, Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2011;22(Supplt A):3A. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garland S, Cottrill E, Markowski L, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in group B Streptococcus: The Australian experience. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:230–5. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.022616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abarzua F, Arias A, Garcia P, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae increase in resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin in vaginal-anal colonization in third quarter of pregnancy in one decade of universal screening. Revista Chilena De Infectologia. 2011;28:334–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florindo C, Viegas S, Paulino A, Rodrigues E, Gomes JP, Borrego MJ. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles in Streptococcus agalactiae colonizing strains: Association of erythromycin resistance with subtype III-1 genetic clone family. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1458–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellano DS, da Silva VL, Nascimento TC, Vieira MD, Diniz CG. Detection of group B Streptococcus in Brazilian pregnant women and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41:1047–55. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220100004000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janapatla R, Ho Y, Yan J, Wu H, Wu J. The prevalence of erythromycin resistance in group B streptococcal isolates at a university hospital in Taiwan. Microb Drug Resist. 2008;14:293–97. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blaschke A, Pulver L, Korgenski K, Savitz L, Daly J, Byington C. Clindamycin-resistant group B Streptococcus and failure of intrapartum prophylaxis to prevent early-onset disease. J Pediatr. 2010;156:501–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiPersio L, DiPersio J. High rates of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance among OBGYN isolates of group B Streptococcus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]