Abstract

Amid numerous complications that plague the health and quality of life of people living with HIV, neurocognitive and psychiatric illnesses pose unique challenges. While there remains uncertainty with respect to the pathophysiology surrounding these disorders, their adverse implications are increasingly recognized. Left undetected, they have the potential to significantly impact patient well being, adherence to antiretroviral treatment and overall health outcomes. As such, early identification of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) and psychiatric illnesses will be paramount in the proactive management of affected patients. The present review focuses on strategies to ensure optimal screening and detection of HAND, depression and substance abuse in routine practice. For each topic, currently available screening methods are discussed. These include identification of risk factors, recognition of relevant symptomatology and an update on validated screening tools that can be efficiently implemented in the clinical setting. Specifically addressed in the present review are the International HIV Dementia Scale, a novel screening equation and algorithm for HAND, as well as brief, validated, verbal questionnaires for detection of depression and substance abuse. Adequate understanding and usage of these screening mechanisms can ensure effective use of resources by distinguishing patients who require referral for more extensive diagnostic procedures from those who likely do not.

Keywords: Depression, HIV, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, Screening, Substance use disorders

Abstract

Parmi les multiples complications qui compromettent la santé et la qualité de vie des personnes qui vivent avec le VIH, les maladies neurocognitives et psychiatriques comportent des défis uniques. Il reste de l’incertitude quant à la physiopathologie de ces troubles, mais leurs conséquences négatives sont de plus en plus établies. Non décelées, elles peuvent nuire considérablement au bien-être du patient, à sa compliance à l’antivirothérapie et à son issue de santé globale. C’est pourquoi il est capital de dépister rapidement les troubles neurocognitifs associés au VIH (TNAV) et les maladies psychiatriques dans la prise en charge proactive des patients atteints. La présente analyse porte sur des stratégies pour garantir le dépistage et la détection optimales des TNAV, de la dépression et de la consommation abusive d’alcool et de drogues dans la pratique habituelle. Pour chaque sujet, les méthodes de dépistage existantes sont exposées,soitladéterminationdesfacteursderisqueetdelasymptomatologie pertinente ainsi qu’une mise à jour des outils de dépistage validés qui peuvent être mis en œuvre avec efficacité en milieu clinique. L’échelle de démence du VIH, un nouvel outil et algorithme de dépistage des TNAV et de brefs questionnaires verbaux validés pour déceler la dépression et la consommation excessive d’alcool et de drogues. Si on comprend et qu’on utilise bien ces mécanismes de dépistage, on peut s’assurer d’une utilisation efficace des ressources en séparant les patients qui ont besoin d’être aiguillés vers des interventions diagnostiques plus poussées de ceux qui n’en ont probablement pas besoin.

A mid numerous complications that plague the health and quality of life of people living with HIV, neurocognitive and psychiatric illnesses pose a unique challenge. Left undetected, they may have a significant effect on adherence to antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, health outcomes and overall well being (1,2).

Furthermore, because there is considerable symptomatic overlap between various mental changes and somatic illnesses, it is often challenging to distinguish one from another (1). Clinical experience has indicated that considering a differential diagnosis that includes the following may be important when assessing neurocognitive or psychiatric challenges encountered in HIV management:

Depression (primary underlying comorbid illness)

Drug-related mental changes

Substance abuse

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND)

Sleep apnea or other sleep disorders

Metabolic disorder (hypothyroidism or hypogonadism)

Adult attention deficit disorder

Beyond this, currently available screening tools must be used effectively to hone in on the presence of potential neurocognitive or psychiatric illness to ensure that the appropriate referrals are made and/or treatment is provided in a timely manner. The present review focuses on the screening and detection of mental illness in HIV-infected individuals, with a primary focus on HAND, depression and substance abuse, because they represent some of the more commonly emerging mental challenges in the management of HIV. Within the present review, a strong emphasis is placed on strategies and tools that can be easily administered by clinicians; as such, established risk factors, commonly observed symptomatology and validated screeners have been presented clearly to ensure accessibility. The objective was to help identify patients who may benefit from specialized neurocognitive or psychiatric testing and/or referrals. A brief review of management strategies is provided but is not intended to replace currently available recommendations from evidence-based guidelines.

METHODS

All topics included within the present review were selected and discussed extensively during a day-long, live meeting attended by the authors. Key words identified during this meeting included “adverse events”, “clinical”, “comorbid”, “depression”, “detection”, “HIV”, “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder”, “impairment”, “mental”, “neuropsychiatric”, “prevalence”, “substance use” and “symptoms”.

These key words were used to search the PubMed database for relevant articles published between 2000 and 2010, giving preference to articles published between 2005 and 2010. Older publications were included if they were either commonly referenced or well regarded. Reference lists for all articles identified using the above search were consulted and the relevant publications used.

Key word searches were also performed across the abstract databases of internationally-recognized HIV clinical conferences (Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections and International AIDS Conference) for abstracts presented between 2008 and 2010.

In addition, widely recognized resources, including the American Psychiatric Association, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatment, Department of Health and Human Services, European AIDS Clinical Society, Health Canada and HIV Clinical Resource (www.hivguidelines.org) were consulted, where appropriate, to further supplement findings from the literature searches.

HAND PERSISTS DESPITE EFFECTIVE TREATMENT

As outlined by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the term ‘HAND’ describes three categories of neurocognitive impairment, which include (from mildest to most severe): asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) and HIV-associated dementia (HAD) (3).

The three subcategories of HAND primarily differ according to severity of cognitive and functional impairment and have varying impacts on activities of daily living (3,4) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) criteria

|

Asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI)*

|

|

|

Mild neurocognitive disorder (MND)*

|

|

|

HIV-associated dementia (HAD)*

|

|

If there is a previous diagnosis of ANI, MND or HAD, but currently the individual does not meet criteria, the diagnosis of ANI, MND or HAD in remission can be made;

Neuropsychological assessment must survey at least the following abilities: verbal/language, attention/working memory, abstraction/executive, memory (learning recall), speed of information processing, sensory-perceptual, motor skills;

If the individual with suspected ANI, MND or HAD also satisfied criteria for a major depressive episode or substance dependence, the diagnose of HAND should be deferred to a subsequent examination conducted at a time when the major depression has remitted or at least one month after cessation of substance use (Adapted from references 3 and 4)

Risk factors for HAND include older age, history of central nervous system (CNS) disease, shorter combination ARV therapy (cART) duration, lower CD4+ cell count and insulin resistance (5,6).

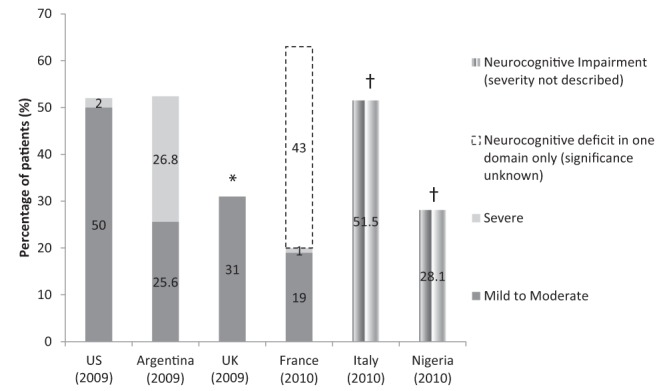

The prevalence of HAND has been reported by several groups and remains high, despite the availability of potent ARV regimens. To date, reported prevalence rates of neurocognitive impairment have ranged between 30% and 60% (7–12) (Figure 1). While there remains some inconsistency in the definitions used when reporting HAND across studies, accumulating evidence indicates that severe impairment is no longer common and that a relatively larger proportion of HIV-infected individuals may be asymptomatically or mildly impaired. However, most studies do not concomitantly assess the rate of neurocognitive impairment among seronegative patients, providing little insight into how the general population might perform on commonly used tests. Given the potential for milder impairment to lead to more severe forms of HAND, screening for HAND across ‘higher-risk’ patients has been advocated by some authors (3).

Figure 1).

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders prevalence rates. Gray bars represent mild to moderate impairment; light gray bars represent severe impairment; white bars with dashed outline represent neurocognitive deficit in one domain only (significance unknown) and multistriped bars represent neurocognitive impairment (severity not described). *Severe neurocognitive impairment rates were not reported in this study.†These studies reported the proportions of HIV-infected patients who were neurocognitively impaired versus normal; they did not differentiate the severities of impairment. Data adapted from references 7–12. US United States; UK United Kingdom

Clinical features of HAND

The absence of symptoms in patients’ daily lives makes ANI difficult to diagnose, particularly without the use of neuropsychological screening and testing. In contrast, patients with MND and HAD may present with more characteristic symptoms, which may be more readily observed before testing. It is believed that detection of ANI may encourage more frequent neurological follow-up, thus, helping to identify patients at earlier stages of functional impairment that could lead to MND or HAD (3). Clinical features and typical patient-reported symptoms are listed in Table 2(13).

TABLE 2.

Clinical and patient-reported symptoms of mild neurocognitive disorder and HIV-associated dementia

|

Mild neurocognitive disorder

| |

| Clinical features | Patient complaints/report |

| Mild impairment in functioning | Difficulty with complex tasks |

| Impaired attention/concentration | Mild memory problems |

| Impaired coordination | Some distractibility |

| Slowed movements | Needs to make lists |

| Emotional lability | Makes excuses for forgetting |

| Adherence problems | |

|

HIV-associated dementia

| |

| Clinical features | Patient complaints/report |

| Cognitive/motor/behavioural problems | Marked memory problems |

| Easily distracted (during conversation, etc) | |

| Slowed decision making | Inability to keep up with work |

| Speech/language problems | Fatigued/slow |

| Abstraction/reasoning problems | Complains of clumsiness/poor balance |

| Visuospatial skill problems | Anger/irritability |

| Attention/concentration problems | Depressed mood/sadness |

| Memory/learning impairment | Late stages: may not realize/complain of symptoms |

Table adapted from reference 13

Practical screening strategies for the detection of HAND

Diagnoses of HAND in the primary care setting often poses a practical challenge due to the time-consuming nature of neuropsychological testing and the lack of access to the various tests and required resources. As such, there may be value in the use of short, sensitive screeners that are not time intensive or complicated to implement.

In this regard, the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS), a brief, five-question screener initially developed to detect severe impairment, was recently validated by Simioni et al (14) to be highly sensitive and specific for mild forms of impairment. The group determined that a score ≤14 is predictive of HAND and should warrant further neuropsychological testing. An abbreviated (three-question) version of the HDS, known as the International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) has been developed and validated across culturally distinct patient populations; however, the IHDS has not been validated to screen for milder forms of HAND to date (15) (Table 3). Both scales have been compared with the established Mini Mental Status Evaluation and have demonstrated improved capability for the detection of HAND (16).

TABLE 3.

International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) screening questionnaire

|

Memory-registration

| |

| Give four words to recall (dog, hat, bean, red) – 1 sec to say each. Then ask the patient all four words after you have said them. Repeat words if the patient does not recall them all immediately. Tell the patient you will ask for recall of the words again a bit later. | |

| Directions | Scoring |

|

| |

| Motor speed: Have the patient tap the first two fingers of the nondominant hand as widely and as quickly as possible. | 4 = 15 in 5 sec |

| 3 = 11–14 in 5 sec | |

| 2 = 7–10 in 5 sec | |

| 1 = 3–6 in 5 sec | |

| 0 = 0–2 in 5 sec | |

Psychomotor speed: Have the patient perform the following movements with the nondominant hand as quickly as possible:

Demonstrate and have patient perform twice for practice. |

(A “sequence” indicates one complete set of actions, in the correct order.) |

| 4 = 4 sequences in 10 sec | |

| 3 = 3 sequences in 10 sec | |

| 2 = 2 sequences in 10 sec | |

| 1 = 1 sequence in 10 sec | |

| 0 = unable to perform | |

| Memory-recall: Ask the patient to recall the four words. For words not recalled, prompt with a semantic clue as follows: animal (dog); piece of clothing (hat); vegetable (bean); color (red). | 1 for each word spontaneously recalled |

| 0.5 for each correct answer after prompting | |

| Maximum = 4 points | |

| Scoring: Maximum score is 12. A score ≤10 warrants further assessment | |

Adapted with permission from reference 15

Recently, Cysique et al (6) published a sensitive (78%) and specific (70%) equation developed to predict the risk of HAND among patients with advanced disease (CD4+ cell count <200 cells/μL and the presence of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention AIDS indicators [17]). The group indicated that higher scores in the presence of clinical symptoms may help determine the need for more formal neurological assessment. In this equation, CNS disease encompassed any HIV-related brain disease, excluding neurological and psychiatric illness. A score ≥ 0 suggests that the patient is at a higher risk of developing HAND. The equation was estimated to take a total of 3 min to complete. Although future studies will attempt to include more predictive factors in the equation, the group recommended the use of the equation among HIV-infected Caucasian men with advanced disease.

Neurophyscological impairment (6):

To facilitate the use of the equation, Cysique et al (6) provided an algorithm for its implementation, which describes proposed therapeutic management considerations for HAND (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Suggested algorithm for the detection and management of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). cART Combination anti-retroviral therapy; CNS Central nervous system. Reproduced with permission from reference 6

Should HAND be suspected following screening, patients may be referred to a psychiatrist or neurologist for assessment with a standard neuropsychological battery or mental status evaluation to diagnose HAND (3).

Management considerations for neurocognitive impairment

To date, cART remains the most effective treatment for HAND. Recent evidence suggests that ARV regimens that are better able to penetrate into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), may lead to better outcomes (18,19). To this extent, Letendre et al (20,21) of the CNS HIV ARV Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) team developed the CNS penetration effectiveness (CPE) ARV ranking system to differentiate ARVs according to their ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier into the CSF. These rankings were hierarchically based on: clinical effectiveness in reducing CSF viral load or improving cognition; the ability for CSF concentrations to be above the half maximal inhibitory concentration; and chemical properties suggesting CNS penetration. Based on these criteria, higher scoring ARV regimens are believed to be associated with improved neurocognitive outcomes (20). (The CPE ranking system has been updated since its initial version; the most recently available rankings are presented in Table 4.) Given that highly active ARV therapy has demonstrated efficacy in HAD, it might be reasonable to suggest that CNS-penetrating ARV therapy might lead to clinical improvement among patients with milder forms of neurocognitive impairment. However, clinical trials that confirm these reports have not been performed. Thus, while it may be safe to use specific regimens in patients with neurocognitive impairment, the absence of more concrete data preclude the establishment of a formal, universal consensus on the treatment of HAND.

TABLE 4.

Central nervous system penetration effectiveness ranking* of antiretrovirals

|

Central nervous system penetration

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best (4) | Moderately good (3) | Moderately poor (2) | Poor (1) | |

| PI | Indinavir/r | Lopinavir/r | Atazanavir/r | Nelfinavir |

| Darunavir/r | Atazanavir | Ritonavir | ||

| Fosamprenavir/r | Fosamprenavir | Saquinavir/r | ||

| Indinavir | Saquinavir | |||

| Tipranavir/r | ||||

| NNRTI | Nevirapine | Delavirdine | Etravirine | |

| Efavirenz | ||||

| NRTI | Zidovudine | Abacavir | Didanosine | Tenofovir |

| Emtricitabine | Lamivudine | Zalcitabine | ||

| Stavudine | ||||

| Other | Maraviroc | Enfuvirtide | ||

| Raltegravir | ||||

Numbers in parentheses indicate rank. NNRTI Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI Protease inhibitor; r Ritonavir. Table adapted with permission from reference 21

Nonetheless, the European AIDS Clinical Society guidelines (22) currently recommend that a diagnosis of HAND would warrant ensuring that patients are receiving at least two ARVs that are known to penetrate the CNS. The guidelines also reiterate the need to check for previous ARV resistance and, where feasible, CSF and plasma viral loads, before modifying the regimen.

MAJOR DEPRESSION: THE MOST COMMON PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS IN HIV MANAGEMENT

Depression is at least twice as common among people living with HIV/AIDS compared with the general population and can develop as a primary, underlying disorder or as a result of the HIV infection, coping, its treatment and/or substance abuse (23,24). Depressed mood is associated with poorer disease course and health-risk behaviour. Depressive symptoms in patients living with HIV have been related to more rapid decline in the number of CD4+ cells, disease progression and mortality (25).

Among seropositive individuals, several socioeconomic and health-related factors have been identified as being risk factors for depression. These include high viral load, low CD4+ cell count, signs of AIDS symptoms, severe neurological or somatic comorbidity, substance abuse, history of depression, female sex, old age, adolescence, lack of sexual partner in the past month, living alone, low income, unemployment, low level of education, lack of health insurance and use of efavirenz (EFV) (22,26). Awareness of factors that might increase the likelihood of depression can help ensure that high-risk patients can be identified at earlier stages and managed in a timely manner.

Practical screening strategies for the detection of major depression

Historically, detection of depression has proven challenging within the general population. In fact, depression may be underdiagnosed among seropositive individuals, at least partly owing to the effect of overlapping somatic symptoms such as fatigue and sleep or appetite changes (1,2). Moreover, our current management strategies are limited in their specificity for our patient population and often draw on evidence from studies of seronegative patients.

Well known screener scales include the Beck Depression Inventory, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Rating Scale, Quick Inventory of Depression Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire (27). While many of these scales may be useful for their screening and diagnostic value, they may not be readily adopted by most primary care clinicians due to time constraints. In such an instance, it may be useful to verbally screen patients first to assess whether there is a need for more formalized assessment. A short verbal interview addressing the main symptom domains outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition can help identify whether further investigation is required (28). The following two questions have demonstrated a sensitivity of 97% (95% CI 83% to 99%) and specificity of 67% (95% CI 62% to 72%) when asked verbally; similar sensitivity and specificity were shown when the questions were posed in a written, questionnaire format (28,29):

During the past month have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

During the past month have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?

Patients identified through screening may undergo diagnostic evaluation based on criteria outlined by established management guidelines (27).

Management considerations for major depression

Overall, there is a lack of randomized controlled trials in the field with respect to currently available treatment modalities for the management of patients with major depression. Moreover, available clinical trials have focused on the general population, with very few trials studying depression in the HIV-seropositive population. As such, management strategies tailored specifically to the needs of patients with HIV have not been established. Thus, management of depressed HIV-infected patients typically follows management guidelines developed to address seronegative patients (27). In the seropositive population, a greater emphasis may be placed on the potential for drug-drug interactions between ARVs and commonly used antidepressants; some ARVs are potent inhibitors and inducers of certain cytochromes and may influence drug levels of other ARVs and/or antidepressants. The Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic (Toronto, Ontario) has developed comprehensive tables that describe the various interactions between ARVs and antidepressants (as well as other classes of medications) (www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html) (30).

Pharmacotherapy in combination with psychotherapy may also be an effective strategy (27). Utilization of an interdisciplinary health care approach, including a pharmacist, psychiatrist and/or counsellor, where available, will be valuable in this respect. The relationship between depressed mood and poor adherence to ARV is well documented (31). Safren et al (25) found that a cognitive behavioural intervention improved adherence by 25% in HIV-positive patients struggling with depression and adherence. Himelhoch and Medoff (32), and Himelhoch et al (33) performed two meta-analyses of randomized double-blinded controlled trials of antidepressants and group psychotherapy targeting depressive symptoms in HIV-infected patients. They found that antidepressant medication is effective in improving depression in HIV-positive men in an outpatient setting. The under-representation of women in the studies limited the generalizability of the findings in this group and suggests that future studies should target this population (32). The same group, found that group therapy, particularly cognitive behavioural therapy, was effective in treating depression in HIV-infected individuals (33).

Evidence and clinical experience have suggested a role for certain ARVs in the induction of neuropsychiatric events among patients (34–37). This may often be a treatment-limiting effect of EFV, a commonly used non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; however, recent case reports of neuropsychiatric events with raltegravir (RAL) use have also emerged (35–38).

Reported side effects of EFV include mood changes, irritability, nightmares, vivid dreams, dizziness, nervousness, fatigue, insomnia and impaired concentration, with major depression, hallucinations and suicide attempts among the more severe, persistent effects (24,35,36).

Across pivotal clinical trials, EFV was associated with a higher incidence of CNS adverse events (52.7% versus 24.6% control groups). Specifically, depression was experienced by 19% of patients receiving EFV compared with 16% in control groups; severe depression was reported by 2.4% versus 0.9% of patients in control groups. In these trials, anxiety was also reported with EFV (13% versus 9% control group) (38). However, in three recent clinical trials, EFV was not associated with higher rates of depression versus the respective comparators. In these studies, neuropsychiatric effects reported at a higher rate in the EFV arms were comprised primarily of sleep disturbances (abnormal dreams, nightmares, sleep disorders) and dizziness or vertigo (39–41).

Several studies have suggested that certain individuals have a polymorphism of the CYP2B6 isoenzyme that produces higher plasma concentrations of EFV, which may be linked to a higher rate of CNS adverse events (42). However, EFV-CNS adverse events may also occur independently of plasma concentrations of the drug (43). As a result, therapeutic drug monitoring to manage EFV-related adverse events is inconsistently recommended in guidelines at this time (22,44,45).

Emergence of neuropsychiatric side effects are often highly concerning to patients and could lead to nonadherence to the ARV regimen, especially if they persist. As a result, guidelines recommend that discontinuation of EFV be considered in some patients if symptoms persist beyond two to four weeks (44). The emergence of symptoms at later stages of EFV treatment might warrant referral to a psychiatrist for further investigation.

Neuropsychiatric events with RAL have, to date, been limited to six published case reports involving the exacerbation of pre-existing depressive symptoms and emergence of insomnia, which resolved on discontinuation of RAL (37,38). In pivotal clinical trials of RAL, psychiatric adverse events occurred at rates that were comparable with placebo (46). For now, longer-term experience is required to better determine the extent to which RAL is associated with these adverse events.

ADDRESSING THE TRIPLE COMORBIDITY: HIV, SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND MENTAL ILLNESS

Substance use (drugs or alcohol) has long been recognized to go hand-in-hand with mental illness; individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) are at an elevated risk of psychiatric illness and individuals with psychiatric illness are more likely to develop SUDs (47–49). In fact, an early analysis of data from the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study (48) demonstrated that greater than one-half of all patients with a lifetime history of a drug abuse disorder had a comorbid mental illness and that mental disorders were up to 4.5-times more common among patients with a history of drug dependence disorders. In fact, a fourth comorbidity exists in relation to this patient group. Hepatitis C infection is prevalent among injection drug users and pegylated-interferon/ribavirin treatment is associated with the emergence of neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression (50,51). Thus, the contribution of drug and alcohol dependence to psychiatric illness in our patients cannot be underestimated.

Practical screening strategies for the detection of SUDs

According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services Guidelines (Section: HIV and Illicit Drug Users), the first step to managing SUDs is recognition of the SUD. To this extent, alcohol abuse can be detected using a range of available screeners. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, developed in collaboration with the WHO is able to identify early symptoms of alcohol abuse as opposed to symptoms associated with dependency. This scale has also shown utility in screening women and minorities (52–54). A total score of ≥8 suggests hazardous and harmful alcohol abuse.

CAGE is a shorter, simpler screener, which has demonstrated efficacy in detecting ongoing alcohol abuse and dependence (54). The following questions comprise the CAGE screener:

C – Have you ever felt that you should cut down on your drinking?

A – Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

G – Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?

E – Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover? (eye-opener)

The CAGE screener has also been validated in an adaptation (CAGE-AID) which expands the focus of each question from alcohol alone, to alcohol and drug use (ie, “Have you ever felt that you should cut down on your drinking and/or drug use?). One or more positive responses indicate a positive screen, warranting further assessment (55).

Currently, a widely-recognized, validated screener for the assessment of mental illness in individuals with substance abuse disorders does not exist.

Management considerations for SUDs

Effective management of this patient population truly hinges on an interdisciplinary effort that focuses on the ongoing challenges of psychosocial counselling for addiction, management of comorbid illness, drug interactions and ARV adherence. Participation in substance abuse treatment programs is a crucial component of HIV management among these patients; adherence support programs have also proven to be valuable in this population (45).

Overall, more trials that assess the population of ‘triply comorbid’ patients may assist in establishing recommendations specific to this population.

CLOSING REMARKS

In a short period of time, significant advances have been made in ensuring that our patients have access to effective treatment and the best possible care. Today, newer challenges have emerged to the forefront prompting us to shift our focus toward ensuring our patients receive support tailored to their individual needs.

However, because we manage psychiatric challenges among our patients, there is still much progress to be made. Relevant questions that remain to be addressed include the following:

Beyond the potential to transition to more severe forms of HAND, what is the clinical significance of ANI?

The data on the CPE score are highly controversial and more studies are necessary to support this approach in guiding therapy.

What are appropriate management strategies for HAND?

Is there a need to develop and test depression tools specific to the HIV-infected population?

How can we improve on and tailor SUD management strategies to the HIV-patient population?

Is there a need to develop screening tools to identify depression or comorbid psychiatric illness specifically among HIV-infected patients?

While we have highlighted important mental issues that face our patients today, it is important to remember that the topics discussed in the present report represent only some of the myriad mental challenges that may affect our patients as they live longer with HIV. With this in mind, continued emphasis must be placed on the individualization of our management strategies to ensure that we address the unique mental challenges faced by our patients in the post-highly active antiretroviral therapy era.

Acknowledgments

The present article was written by Dr Adriana Carvalhal, Dr Jean-Guy Baril, Dr Frederic Crouzat, Dr Joss De Wet, Dr Patrice Junod, Dr Colin Kovacs and Nancy Sheehan with the help of a medical writer – Neha Kumar of ANTIBODY Healthcare Communications.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors were renumerated by Abbott Laboratories Limited for their travel logistics and participation ($2,000 per attendee) in a workshop meeting designed to facilitate information exchange on the topic of psychiatric illness and its management in HIV-positive individuals. Given identification of a need for publications on this topic area, authors decided on the development of the manuscript for potential publication. Thus, the authors developed the present manuscript following the aforementioned meeting, using some of the insights gained therein. However, the authors did not receive any financial support for the preparation of the manuscript. The medical writer was sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant provided by Abbott Laboratories Limited, for time spent preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brogan K, Lux J. Management of common psychiatric conditions in the HIV-positive population. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6:108–15. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodkjaer L, Laursen T, Balle N, Sodemann N. Depression in patients with HIV is under-diagnosed: A cross-sectional study in Denmark. HIV Medicine. 2010;11:46–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker J, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–99. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant I. Neurocognitive disturbances in HIV. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:33–47. doi: 10.1080/09540260701877894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valcour V, Sacktor N, Paul R, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with cognition among HIV-1-infected patients: The Hawaii Aging with HIV cohort. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2006;43:405–10. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243119.67529.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cysique L, Murray JM, Dunbar M, Jeyakumar V, Brew BJ. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Medicine. 2010;11:642–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaton R, Franklin D, Clifford D, et al. Persistence and progression of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment (NCI) in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (CART) and the role of comorbidities: The CHARTER study (Abst). 5th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Cape Town. July 19 to 22. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodkin K, Cahn P, Concha M, et al. Prevalence of HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders in Argentina (Abst). 5th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Cape Town. July 19 to 22, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garvey L, Yerrakalva D, Winston A. High rates of asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (aNCI) in HIV-1 infected subjects receiving stable combination anti-retroviral therapy (CART) with undetectable plasma HIV RNA (Abst). 5th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Cape Town. July 19 to 22, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vassallo M, Harvey-Langton A, Malandain G, et al. The Neuradapt Study: Clinical, radiological and immunovirologic findings in patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (Abst). 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco. February 16 to 19, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Di Giambenedetto S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of minor neurocognitive disorders in asymptomatic HIV-infected outpatients (Abst). 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco. February 16 to 19, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royal W, Akomolafe A, Habib A, et al. Neurocognitive impairment and HIV in Nigeria: Functional and virologic correlates (Abst). 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco. February 16 to 19, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.HIV Clinical Resource. New York: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins University Division of Infectious Diseases; c2000-2011 < www.hivguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/Dec09AINeuro.ppt> (Accessed March 25, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni J-M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24:1243–50. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283354a7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale: A new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skinner S, Adewale AJ, DeBlock L, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurocognitive screening tools in HIV/AIDS: Comparative performance among patients exposed to antiretroviral therapy. HIV Medicine. 2009;10:246–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HIV classification: CDC and WHO Staging Systems. United States of America: AIDS Education and Treatment Centers National Resource Centre; c2011. < www.aidsetc.org/aidsetc?page=cm-105_disease#t-3>. (Accessed March 25, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cysique L, Vaida F, Letendre S, et al. Dynamics of cognitive change in impaired HIV-positive patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Neurology. 2009;73:342–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Salvatori M, et al. Changes in cognition during antiretroviral therapy: Comparison of 2 different ranking systems to measure antiretroviral drug efficacy on HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2009;52:56–63. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181af83d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Capparelli E, et al. Validation of the CNS penetration-effectiveness rank for quantifying antiretroviral penetration into the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:65–70. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letendre S, Ellis T, Deutsch R, et al. Correlates of time-to-loss-of-viral-response in CSF and plasma in the CHARTER Cohort (Abst). 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco. February 16 to 19, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) Guidelines: Clinical management of treatment of HIV infected adults in Europe. Version 6. < www.europeanaidsclinicalsociety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=59&Itemid=41> (Accessed March 25, 2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arendt G. Affective disorders in patients with HIV infection. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:507–18. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safren S, O’Cleirigh C, Tan J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected Individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campos L, Bonolo P, Guimaraes M. Anxiety and depression assessment prior to initiating antiretroviral treatment in Brazil. AIDS Care. 2006;18:529–36. doi: 10.1080/09540120500221704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Guidelines: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:S1–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327:1144–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whooley M, Avins A, Miranda J, Browner W. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic Drug interaction tables 2010. < www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html> (Accessed March 25, 2011).

- 31.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk for noncompliance with medical treatment meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Int Med. 2000;160:2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himelhoch S, Medoff D. Efficacy of antidepressant medication among HIV-positive individuals with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:813–22. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Himelhoch S, Medoff D, Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:732–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fumaz CR, Muňoz-Moreno JA, Moltó J, et al. Long-term neuropsychiatric disorders on efavirenz-based approaches: Quality of life, psychologic issues, and adherence. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2005;38:560–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000147523.41993.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lochet P, Peyrière H, Lotthé A, Mauboussin J, Delmas B, Reynes J. Long-term assessment of neuropsychiatric adverse reactions associated with efavirenz. HIV Medicine. 2003;4:62–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris M, Larsen G, Montaner JG. Exacerbation of depression associated with starting raltegravir: A report of four cases. AIDS. 2008;22:1890–2. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e0169. (Lett). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gray J, Young B. Acute onset insomnia associated with the initiation of raltegravir: A report of two cases and literature review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:689–90. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0012. (Lett). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada; Nov 26, 2010. Sustiva (efavirenz) Canadian Product Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pozniak AL, Morales-Ramirez J, Katabira E, et al. Efficacy and safety of TMC278 in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-1 patients: Week 96 results of a phase IIb randomized trial. AIDS. 2010;24:55–65. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833032ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson M, Stellbrink H-J, Podzamczer D, et al. A comparison of neuropsychiatric adverse events during 12 weeks of treatment with etravirine and efavirenz in a treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected population. AIDS. 2011;25:335–40. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283416873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Berger DS, et al. Raltegravir versus efavirenz regimens in treatment-naïve HIV-1–infected patients: 96-week efficacy, durability, subgroup, safety, and metabolic analyses. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2010;55:39–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181da1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rotger M, Colombo S, Furrer H, et al. Influence of CYP2B6 polymorphism on plasma and intracellular concentrations and toxicity of efavirenz and nevirapine in HIV-infected patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi M, Ibe S, Kudaka Y, et al. No observable correlation between central nervous system side effects and EFV plasma concentrations in Japanese HIV type 1-infected patients treated with EFV containing HAART. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:983–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Department of Health and Human Services Panel on ARV Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents Guidelines: Guidelines for the use of ARV agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. < www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-treatment-guidelines/0/> (Accessed March 25, 2011).

- 45.Santé et Services sociaux Québec Guidelines: La thérapie antirétrovirale pour les adultes infectés par le VIH, guide pour les professionnels de la santé du Québec. < http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/acrobat/f/documentation/2010/10-337-02.pdf> (Accessed March 25, 2011).

- 46.Isentress (raltegravir) Canadian Product Monograph. Merck Frosst Canada, Ltd; Jan 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regier D, Farmer M, Rae D, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bing E, Burnam M, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:729–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merikangas K, Mehta R, Molnar B, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: Results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav. 1998;23:893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Latimer W, Hedden S, Floyd L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Hepatitis C among injection drug users: The significance of duration of use, incarceration and race/ethnicity. J Drug Issues. 2009;39:893–904. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fumaz C, Muňoz-Moreno J, Ballesteros A, et al. Influence of the type of pegylated interferon on the onset of depressive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in HIV-HCV coinfected patients. AIDS Care. 2007;19:138–45. doi: 10.1080/09540120600645539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saunders J, Aasland O, Babor T, de la Fuente J, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption – II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fiellin D, Reid M, O’Connor P. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1977–89. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reinert D, Allen J. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:272–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown R, Rounds L. Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: Criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wis Med J. 1995;94:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]