Abstract

Cell cycle transitions are driven by the periodic oscillations of cyclins, which bind and activate CDKs (cyclin-dependent kinases) to phosphorylate target substrates. Cyclin F uses a substrate recruitment strategy similar to that of the other cyclins, but its associated catalytic activity is substantially different. Indeed, cyclin F is the founding member of the F-box family of proteins, which are the substrate recognition subunits of SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein) ubiquitin ligase complexes. Here, we discuss cyclin F function and recently identified substrates of SCFcyclin F involved in dNTP production, centrosome duplication, and spindle formation. We highlight the relevance of cyclin F in controlling genome stability through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and the implications for cancer development.

Introduction

In each cell division cycle, cells replicate their DNA (in S-phase) and equally distribute the genetic information to the daughter cells (in M-phase). Cell cycle phases are driven by the periodic activity of cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), whose activities are controlled by the oscillations of the cyclins, the obligate CDK activators. CDK activity drives cell cycle phase transitions in a very accurate and ordered manner, and these transitions can be blocked by multiple checkpoint mechanisms that monitor each phase for completion and fidelity [1]. In addition to CDKs, cell cycle transitions and checkpoints are also regulated by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis that ensures rapid elimination of target proteins. Briefly, protein substrates are covalently tagged with chains of the small protein ubiquitin, directing recruitment of the substrates to the proteasome for proteolysis. The polyubiquitin chain is assembled on the substrate protein via an enzymatic cascade, in which ubiquitin is activated through an ATP-dependent reaction that results in a thioester linkage to an E1 ubiquitin activating enzyme, which, in turn, transfers the ubiquitin moiety to an E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (UBC). The majority of E3 ubiquitin ligases function by bringing together substrates with UBCs, which mediate the transfer of ubiquitin to a lysine residue in the substrate. Thus, the ultimate regulation of the reaction is dictated by a large family of E3s, which determine substrate specificity. The irreversible nature of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis allows fast and controlled transition from one cell cycle phase to the next [2].

In 1994, the Elledge laboratory identified a new mammalian cyclin as a suppressor of a S. cerevisiae cdc4 mutant (deficient in the G1/S transition) [3], and following the alphabetic nomenclature for mammalian cyclins, it was named cyclin F. Cyclin F is expressed during S phase and peaks during the G2 phase of the cell cycle. Independently, the Frischauf laboratory identified cyclin F as a new cyclin with unknown function from a search for candidate genes responsible for polycystic kidney disease in a gene-rich region of chromosome 16p13.3 [4]. Further investigation of cyclin F by Elledge and colleagues identified an important functional domain that was designated the “F-box,” after cyclin F itself [5]. Accordingly, cyclin F is also known as F-box only protein 1 (Fbxo1) and is the founding member of a large family of proteins containing F-box domains present in all eukaryotes [6]. The F-box domain is required for binding to Skp1, a component of the Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein (SCF) ubiquitin ligase machinery. Skp1 binds one of many F-box proteins (69 in human) and, at the same time, recruits Cul1 (and RBX1 with Cul1) to assemble a functional SCF complex. RBX1, in turn, recruits the E2 for ubiquitylation of target substrates [7].

The SCF ubiquitylation system allows the specific recognition of multiple substrates by a single E3 ubiquitin ligase. For example, βTrCP, which is among the best characterized F-box proteins, recognizes and physically binds a degradation motif (degron; typically DSGxxS for βTrCP) in substrates. βTrCP can access the substrate only upon phosphorylation of the serine residues in this DSGxxS motif [8]. This mechanism requires the cooperation of a kinase, conferring further specificity in selection of the substrate that is targeted for degradation. Over 40 βTrCP substrates, involved in very different cellular processes, have been identified so far [9].

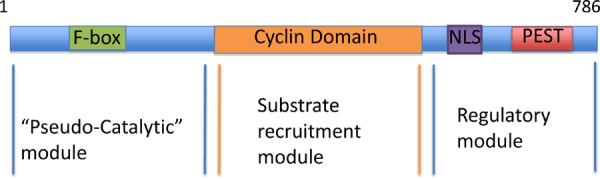

In mice, the cyclin F gene (Ccnf) is essential [10], but despite its importance to development and status as the first F-box protein, its molecular function was unrecognized until recently. Cyclin F may be divided in three separate modules, as depicted in Figure 1: a pseudo-catalytic module, a substrate recruitment module, and a regulatory module. The pseudo-catalytic module contains the F-box domain, which mediates interaction with other components of the SCF for ubiquitylation of target substrates. Because F-box proteins lack intrinsic catalytic activity, but recruit activity through the SCF scaffold, we have defined the F-box domain as pseudo-catalytic.

Fig. 1.

Cyclin F contains three separate modules. A schematic representation of the three cyclin f modules: the pseudo-catalytic, substrate recruitment (cyclin box), regulatory modules.

D'Angiolella et al.,

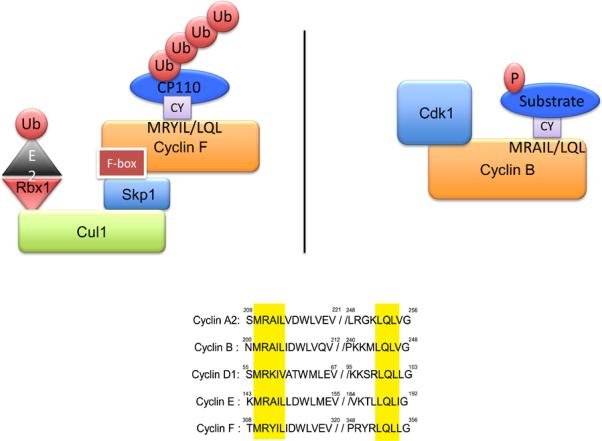

Most of the characterized F-box proteins use phosphorylation as a recognition mechanism to bind their respective substrates (as in the above example of βTrCP). Interestingly, cyclin F utilizes a different strategy to bind its substrates- it uses a hydrophobic patch within the cyclin box domain to bind a CY motif (RxL) in the substrate, in a manner analogous to the binding of other cyclins to CDKs [11]. Indeed, the cyclin box of cyclin F shares homology with the cyclin box domains of other cyclins (Figure 2), but cyclin F uses the F-box domain to promote the ubiquitylation of target substrates, whereas other cyclins (e.g., cyclins A, B, C, D, or E) use the CDK catalytic subunit to phosphorylate target substrates (Figure 2). Interestingly, cyclin F seems to target only a limited subset of known CDK substrates, revealing a certain degree of specificity among different cyclins (and their hydrophobic patches) and/or the presence of a cofactor that modulates such interaction. Therefore, while cyclin F shares a similar domain with other cyclins, its catalytic activity is substantially different.

Fig. 2.

Cyclin F uses a hydrophobic patch to bind the CY motif of target substrates. Cyclin F uses the hydrophobic patch in the cyclin domain to bind CY-containing substrates and through the F-box domain (pseudo-catalytic module) targets them for ubiquitylation and subsequent proteolysis. Cyclin B recruits substrates in a similar manner, but uses the CDK catalytic subunit to phosphorylate target substrates.

D'Angiolella et al.,

The carboxy-terminal region of cyclin F is the regulatory module that controls its nuclear localization [cyclin F localizes to both the nucleus (in S and G2) and the centrosomes (mostly in G2)] as well as its abundance during the cell cycle and following genotoxic stress. This region of cyclin F contains a Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) [12] and a PEST sequence [3, 13], a short stretch of amino acids enriched in proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine that signals for proteolysis. The PEST sequence contains two distinct regions for the regulation of cyclin F levels. One region signals for cyclin F proteolysis in G1 phase, and the other region controls cyclin F proteolysis after DNA damage ([14] and VDA and MP, unpublished results).

Therefore, cyclin F modules underscores both its ability to modulate events taking place during the G2 phase and its regulation by localization and stability.

The Cyclin F-RRM2 axis

Using immuno-purification and mass spectrometry, Ribonucleotide Reductase family Member 2 (RRM2) was identified as an interactor of cyclin F, and it was shown that SCFCyclin F promotes the ubiquitylation and consequent degradation of RRM2 [14].

Ribonucleotide Reductase (RNR) catalyzes the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs) for the synthesis of DNA during replication and repair. Being endowed with such an essential function places RNR among the most highly conserved and regulated enzymes. The catalytic site of RNR is formed when two RRM2 subunits are bound to two Ribonucleotide Reductase family Member 1 (RRM1) subunits. Each RRM1 subunit contains an active site, and each RRM2 subunit contains a non-heme iron center and a stable tyrosyl free radical [15]. A complex and intricate arrangement of regulatory mechanisms control RNR function to ensure timely production of the correct levels of dNTPs. RRM1 levels are constant throughout the cell cycle and are always in excess of the levels of RRM2 [16]. Therefore, the cell cycle-dependent activity of RNR is regulated by the synthesis and degradation of RRM2.

Two different ubiquitin ligases provide tight control over the levels of RRM2 in the G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle. During G1, APC/CCdh1, a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, targets RRM2 for degradation [17]. During G2, cyclin F controls the degradation of RRM2 [14]. As mentioned above, cyclin F, like other cyclins, recognizes substrates that contain the CY motif, and RRM2 contains a CY motif (at position 49 in human RRM2) that mediates binding to cyclin F. However, RRM2 binding is not solely dependent on this CY motif. Threonine 33 (Thr33) of RRM2 needs to be phosphorylated by a G2 CDK for efficient cyclin F binding since this event exposes the CY motif of RRM2 [14]. Levels of phosphorylated Thr33 increase during G2, when levels of RRM2 decrease. Interestingly, Cdh1 recognizes a KEN box at position 29 of RRM2 [17], which is present right before Thr33. A non-phosphorylated peptide containing the KEN box is able to bind Cdh1 in vitro, but an identical peptide in which Thr33 is constitutively phosphorylated does not bind Cdh1 [14]. Therefore, it appears that phosphorylation of Thr33 prevents recognition by Cdh1. This mechanism might prevent RRM2 degradation in G2 phase cells exposed to genotoxic stress, when APC/CCdh1 is re-activated [18].

RRM2 is also phosphorylated on Ser20 by a CDK, but, in contrast to Thr33, which is phosphorylated mostly in G2, Ser20 is phosphorylated mostly in S phase, and the biological significance of this event is not understood [19]. Interestingly, phosphorylation of Thr33 increases when phosphorylation of Ser20 is prevented by point mutation to alanine (VDA and MP, unpublished result). Thus, it is possible that phosphorylation of Ser20 inhibits phosphorylation of Thr33 to prevent unscheduled RRM2 degradation during S-phase.

Cyclin F-mediated degradation of RRM2 is essential to maintain balanced levels of dNTPs. Failure to properly regulate dNTP levels causes genome instability and a hypermutator phenotype. Cells in which cyclin F expression is silenced or cells expressing a stable mutant of RRM2 that escapes cyclin F-mediated degradation accumulate high levels of dNTPs and display an increase in mutation frequency compared to control cells [14]. Such an increase in mutation frequency might be expected to induce neoplastic transformation. However, transgenic mice expressing high levels of RRM2 only develop lung adenocarcinomas with low penetrance [20], indicating that tumorigenesis requires additional factors beyond dNTP imbalance. Indeed, K-Ras expression stimulates a metabolic change characterized by increased levels of RRM2 in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer [21]. In addition to tumor initiation, altered proteolytic regulation of RRM2 might also favor the expansion of dNTP pools and increased genome instability during tumor progression. However, even if there have been no detailed analyses of cyclin F protein levels in cancer, different mutations have been reported. In a breast tumor without germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, cyclin F was rearranged with AC141586.2 [22]. This rearrangement generates an in-frame protein product in which the F-box domain of cyclin F is substituted by the first exon of AC141586.2. Although this seems to be a rare event in breast cancer, it might still contribute to tumorigenesis by increasing the rate of mutations due to RRM2 accumulation. From a therapeutic point of view, cells bearing this translocation might be more sensitive to RNR inhibition. A genome-wide RNAi screen also identified cyclin F as a mediator of neratinib resistance in a breast cancer cell line, suggesting a possible cyclin F mutation or deregulation [23].

dNTPs are not only required for DNA synthesis, but also for DNA repair. Therefore, precise mechanisms control dNTP production following DNA damage. RNR localizes to DNA damage foci to allow production of dNTPs at sites of DNA repair synthesis [24]. In response to a variety of genotoxic stimuli, including gamma irradiation, campotethicin, neocarzinostatin, cisplatin, MMS, and ultraviolet light, cyclin F is degraded, and the drastic drop in cyclin F levels coincides with the accumulation of RRM2 in the nucleus [14]. Cyclin F degradation after DNA damage is necessary to allow this accumulation of RRM2 within the nucleus to facilitate DNA repair [14]. Furthermore, cells expressing wild type cyclin F display a reduced ability to repair damaged DNA despite genotoxic stress compared to cells expressing an inactive cyclin F mutant, supporting a role for cyclin F in the DNA damage response. Because dNTP production is critical for cell survival, additional mechanisms operate following genotoxic stress to regulate the cyclin F-RRM2 axis. For example, cyclin F mRNA levels decrease 6 hours after treatment of B lymphocytes with ionizing radiation [25]. Additionally, four RRM2 transcript variants have been found in zebrafish, and one of the four variants that is most highly expressed following the treatment of embryos with genotoxic stress lacks the first 52 amino acids, where the binding sites for cyclin F and Cdh1 reside. [26]. Thus, both transcriptional and post-translational control appear to prevent RRM2 degradation in G2 cells exposed to genotoxic stress.

The degradation of cyclin F is signaled through ATR via a mechanism that is not well understood [14]. Further exploration of this pathway will be crucial to understand the molecular mechanisms leading to cyclin F degradation. The regulation of cyclin F might reveal more insight into the role of dNTP production after DNA damage. Normally, dNTPs are produced in the cytoplasm. It is only after the cell receives a genotoxic insult that RNR translocates into the nucleus. Currently, the requirement for RNR localization to the site of DNA damage to produce and supply dNTPs is unclear. It is puzzling because dNTPs are freely diffusible through the nuclear pore, and therefore, the nuclear localization of RNR should not be necessary. It has been proposed that RNR localization to sites of DNA damage might prevent incorporation of nucleotides (instead of dNTPs) into the DNA by less proficient polymerases [27, 28]. Measuring the levels of free dNTPs in different cell compartments is technically challenging, and the few methods that are available are based on indirect measurements. Therefore, although the levels of cyclin F and RRM2 appear to be governed by highly organized mechanisms, it will be difficult to understand whether they strictly reflect a similar regulation of dNTP pools.

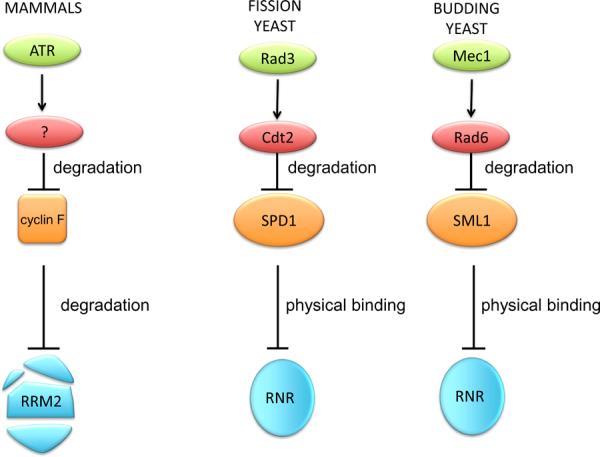

Due to its essential role in maintaining appropriate dNTP pools, RNR is highly conserved through evolution, and the mechanisms of RNR regulation in mammals resemble RNR regulation in yeast. Similar to cyclin F, Spd1 and Sml1 are two inhibitors of RNR in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, respectively [29, 30]. These inhibitors do not promote RRM2 degradation and instead inhibit RNR by physical binding. However, in response to genotoxic stress, the CRL4Cdt2 ubiquitin ligase complex targets Spd1 for degradation [31], and the ubiquitin ligase Ubr2/Rad6 controls the degradation of Sml1 [32] in a mechanism dependent on the two ATR orthologs, Rad3 and Mec1 (Summarized in Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

ATR-dependent regulation of RNR from yeast to mammals. RNR is is among the most well-conserved (from prokaryotes to eukaryotes) and highly-regulated enzymes. Spd1, Sml1, and cyclin F are three inhibitors of RNR in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and mammals, respectively. Whereas cyclin F promotes RRM2 degradation, Spd1 and Sml1 inhibit RNR by physical binding. In response to genotoxic stress, Cdt2 targets Spd1 for degradation,, while Ubr2/Rad6 promotes Sml1 proteolysis. All three events are dependent on ATR or ATR orthologs, (Rad3 and Mec1).

D'Angiolella et al.,

Cyclin F regulation of CP110 and NUSAP

Centrosomes are organelles that determine the geometry of microtubule arrays in mitosis, controlling chromosome segregation and cell division. In cycling cells, centrosomes are duplicated once each cell cycle. In addition to localizing to the nucleus, cyclin F also localizes to the centrosomes, where it controls the levels of CP110, a centrosomal protein that promotes centrosome duplication. Cyclin F regulates the protein levels of CP110 during G2 through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, restricting the centrosome replication to once per cell cycle. Thus, the regulation of CP110 by cyclin F during the cell cycle ensures faithful duplication of centrosomes and avoids mitotic aberrations due to centrosome misregulation [33]. Additional regulation of this process is achieved through the cell cycle inhibitor p27. Ectopic expression of a p27 mutant that binds cyclin F, but not CDKs, induces centrosome amplification and mitotic aberrations by disrupting the interaction between cyclin F and CP110 [34]. The accumulation of p27 in daughter cells soon after cytokinesis may therefore,contribute to the stability of CP110 during G1.

While increased CP110 levels are associated with centrosomal duplication [33, 35], their reduction leads to elongation of the centrioles, a prerequisite for the formation of cilia [36]. Therefore, levels of CP110 should be fine tuned not only during cell cycle progression but also during cilia formation, which occurs in certain quiescent and post-mitotic cells. Besides cyclin F-mediated regulation of CP110, additional mechanisms may contribute to the control of CP110 levels. For example, a different ubiquitin ligase may target CP110 in G0/G1 cell cycle phases and in differentiated cells to enable cilia formation. Moreover, considering that CP110 prevents an excessive elongation of the centrioles [36], a de-ubiquitylating enzyme could act on CP110 at the centrosomes to preserve a minimal amount of CP110 at the site, thus preventing unscheduled cilia formation in G2, when levels and activity of cyclin F peak.

Recently, a comprehensive and elegant approach identified many novel SCF substrates, including NUSAP, which was validated as a substrate of cyclin F [37]. NUSAP is a microtubule-associated protein that plays an important role in spindle assembly. NUSAP deficiency prevents the proper alignment of chromosomes at the metaphase plate, resulting in a mitotic block and early embryonic lethality in mice [38]. Knockdown of cyclin F increases the levels of NUSAP during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [37]. The biological relevance of NUSAP regulation by cyclin F has not been investigated, but it is conceivable that, together with CP110, cyclin F controls NUSAP abundance to regulate the assembly of the mitotic spindle. While NUSAP overexpression induces mitotic arrest and microtubule bundling [39], cyclin F interference does not lead to a similar phenotype [10, 14, 33], indicating that different levels of NUSAP might lead to different phenotypes. Notably, NUSAP was shown to be a target of RanGTP, stabilizing the interaction between microtubules and chromatin [40]; accordingly, localized control of degradation could be crucial for correct organization of the mitotic spindle. Interestingly, a prolonged arrest in nocodazole (a microtubule-depolymerizing agent that stalls cells in prometaphase), leads to reduction of cyclin F levels [13, 14, 33]; this reduction may be due to a feedback mechanism that allows NUSAP accumulation when the spindle is defective.

Future studies may provide insight as to whether cyclin F deregulation contributes to the chromosomal instability observed in human cancers through its action on CP110 and NUSAP. Indeed, increased NUSAP levels have been observed in prostate cancer and are associated with poor outcomes [41]. Further investigation of cyclin F-mediated degradation of NUSAP may lead also to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which the microtubule stabilizing agents used in chemotherapeutic regimens affect cell division.

Concluding remarks

Cyclin F fine-tunes centrosome duplication and DNA synthesis, underscoring the importance of this cyclin for normal cell physiology and transformation. By promoting the elimination of RRM2, cyclin F protects the cell from genome instability, and by inducing CP110 degradation, it prevents chromosome instability. Cyclin F-mediated degradation of RRM2 ensures the maintenance of a balanced pool of dNTPs. Balanced dNTP levels are crucial to prevent the acquisition of mutations through increased misincorporation of ribonucleotides and, at the same time, to provide material for DNA repair in response to genotoxic stress. In this respect, cyclin F-mediated regulation of RRM2 might have clinical implications for cancer treatment. DNA damaging anti-cancer drugs, such as gemcitabine, hydroxyurea, and cisplatin, are used in carcinomas, including non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, and breast cancer. Interestingly, these drugs also interfere with RNR function to varying degrees, and ongoing studies are testing the efficacy of combined treatment strategies. For instance, combined gemcitabine and cisplatin administration is used to produce a synergistic effect in pancreatic cancer and non-small cell lung cancer [42, 43]. Gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells is associated with RRM2 overexpression. Inhibition of RRM2 sensitizes cancer cells to gemcitabine treatment and suppresses tumor growth and metastasis [44]. Overexpression of RRM2 has also been proposed as a mechanism of resistance to hydroxyurea treatment in myelogenous leukemia cells [45]. Stable suppression of RRM2 correlates with a reduction in dATP and dGTP levels and sensitizes colon cancer cells to cisplatin and hydroxyurea treatments [46].

It has been recently shown that one of the most common forms of damage in mammalian cells is due to the incorporation of ribonucleotides instead of deoxyribonucleotides into DNA [47]. Colon cancers frequently exhibit loss or mutation of mismatch repair genes (i.e., Msh2 and Msh6) [48]. Because mismatch repair is involved in the recognition and repair of rNMP incorporated in DNA [49], these tumors might be more sensitive to nucleotide incorporation compared to normal cells. A better understanding of cyclin F-mediated RNR regulation will allow the exploitation of this tumor-specific weakness to develop synthetic lethal strategies and/or aid in the design of novel, targeted therapies. Furthermore, whereas cyclin F degradation ensures rapid accumulation of RRM2 in response to genotoxic stress, a secondary response involves a paralog of RRM2, namely p53R2 (also known as RRM2B), whose transcription is induced by p53 [50]. It is possible that p53R2 is defective in approximately 50% of human cancers bearing p53 mutations, making this another potential weakness to exploit.

The recent RRM2 and cyclin F findings demonstrate that DNA damaging agents elevate the levels of RRM2, leading to production of dNTPs, and this process confers a survival advantage to cells. Therefore, these studies provide the rationale for the inhibition of RNR in combination with DNA damaging drugs. Fine modulation of RRM2 levels could be achieved through blocking cyclin F-mediated degradation, so it will be important to identify the ubiquitin ligase responsible for ATR-dependent degradation of cyclin F. Full elucidation of this mechanism might aid the design of small molecules inhibiting the degradation of cyclin F. Whereas RRM2 levels have been investigated in a large number of cancers, the levels of cyclin F in cancer remain unexplored. However, the limited success of current therapeutic regimens emphasizes the need for molecular profiling of tumors. A careful study of cyclin F levels in RRM2 overexpressing tumors might provide insight into drug resistance, predict response to chemotherapy, and prove to be a powerful tool for the design and implementation of new chemotherapies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. R. Skaar and L. Young for critical reading of the manuscript. Work in the Pagano laboratory is funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM057587, R37-CA076584, and R21-CA161108). MP is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Satyanarayana A, Kaldis P. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene. 2009;28(33):2925–39. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman JS, Skaar JR, Pagano M. SCF ubiquitin ligases in the maintenance of genome stability. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2012;37(2):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai C, Richman R, Elledge SJ. Human cyclin F. The EMBO journal. 1994;13(24):6087–98. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraus B. A novel cyclin gene (CCNF) in the region of the polycystic kidney disease gene (PKD1) Genomics. 1994;24(1):27–33. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai C. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell. 1996;86(2):263–74. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin J. Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F-box proteins. Genes & development. 2004;18(21):2573–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2004;5(9):739–51. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. Stabilizers and destabilizers controlling cell cycle oscillators. Molecular cell. 2006;22(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skaar JR. SnapShot: F Box Proteins II. Cell. 2009;137(7):1358–1358. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tetzlaff MT. Cyclin F disruption compromises placental development and affects normal cell cycle execution. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24(6):2487–98. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2487-2498.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulman BA, Lindstrom DL, Harlow E. Substrate recruitment to cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by a multipurpose docking site on cyclin A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(18):10453–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong M. Cyclin F regulates the nuclear localization of cyclin B1 through a cyclin-cyclin interaction. The EMBO journal. 2000;19(6):1378–88. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fung TK. Cyclin F is degraded during G2-M by mechanisms fundamentally different from other cyclins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(38):35140–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Angiolella V. Cyclin F-mediated degradation of ribonucleotide reductase M2 controls genome integrity and DNA repair. Cell. 2012;149(5):1023–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annual review of biochemistry. 2006;75:681–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chabes A, Thelander L. Controlled protein degradation regulates ribonucleotide reductase activity in proliferating mammalian cells during the normal cell cycle and in response to DNA damage and replication blocks. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(23):17747–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chabes AL. Mouse ribonucleotide reductase R2 protein: a new target for anaphase-promoting complex-Cdh1-mediated proteolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(7):3925–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330774100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassermann F. The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell. 2008;134(2):256–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang LY. Quantitative phosphoproteome profiling of Wnt3a-mediated signaling network: indicating the involvement of ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 subunit phosphorylation at residue serine 20 in canonical Wnt signal transduction. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2007;6(11):1952–67. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700120-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X. Broad overexpression of ribonucleotide reductase genes in mice specifically induces lung neoplasms. Cancer research. 2008;68(8):2652–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying H. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell. 2012;149(3):656–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephens PJ. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462(7276):1005–10. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seyhan AA. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies novel targets of neratinib resistance leading to identification of potential drug resistant genetic markers. Molecular bioSystems. 2012;8(5):1553–70. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05512k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niida H. Essential role of Tip60-dependent recruitment of ribonucleotide reductase at DNA damage sites in DNA repair during G1 phase. Genes & development. 2010;24(4):333–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1863810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyng H. Response of malignant B lymphocytes to ionizing radiation: gene expression and genotype. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2005;115(6):935–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shang H. Identification and characterization of alternative promoters, transcripts and protein isoforms of zebrafish R2 gene. PloS one. 2011;6(8):e24089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu CM. Tumor Cells Require Thymidylate Kinase to Prevent dUTP Incorporation during DNA Repair. Cancer cell. 2012;22(1):36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stover PJ, Weiss RS. Sensitizing Cancer Cells: Is It Really All about U? Cancer cell. 2012;22(1):3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hakansson P. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe replication inhibitor Spd1 regulates ribonucleotide reductase activity and dNTPs by binding to the large Cdc22 subunit. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(3):1778–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X. Mutational and structural analyses of the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 define its Rnr1 interaction domain whose inactivation allows suppression of mec1 and rad53 lethality. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20(23):9076–83. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9076-9083.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss J. Break-induced ATR and Ddb1-Cul4(Cdt)(2) ubiquitin ligase-dependent nucleotide synthesis promotes homologous recombination repair in fission yeast. Genes & development. 2010;24(23):2705–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.1970810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andreson BL. The ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, Sml1, is sequentially phosphorylated, ubiquitylated and degraded in response to DNA damage. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(19):6490–501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Angiolella V. SCF(Cyclin F) controls centrosome homeostasis and mitotic fidelity through CP110 degradation. Nature. 2010;466(7302):138–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma SS. A p27(Kip1) mutant that does not inhibit CDK activity promotes centrosome amplification and micronucleation. Oncogene. 2012;31(35):3989–98. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J. Neurl4, a novel daughter centriole protein, prevents formation of ectopic microtubule organizing centres. EMBO reports. 2012;13(6):547–53. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spektor A. Cep97 and CP110 suppress a cilia assembly program. Cell. 2007;130(4):678–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emanuele MJ. Global identification of modular cullin-RING ligase substrates. Cell. 2011;147(2):459–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanden Bosch A. NuSAP is essential for chromatin-induced spindle formation during early embryogenesis. Journal of cell science. 2010;123(Pt 19):3244–55. doi: 10.1242/jcs.063875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raemaekers T. NuSAP, a novel microtubule-associated protein involved in mitotic spindle organization. The Journal of cell biology. 2003;162(6):1017–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ribbeck K. NuSAP, a mitotic RanGTP target that stabilizes and cross-links microtubules. Molecular biology of the cell. 2006;17(6):2646–60. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gulzar ZG, McKenney JK, Brooks JD. Increased expression of NuSAP in recurrent prostate cancer is mediated by E2F1. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinemann V. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(24):3946–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandler AB. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(1):122–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duxbury MS. RNA interference targeting the M2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase enhances pancreatic adenocarcinoma chemosensitivity to gemcitabine. Oncogene. 2004;23(8):1539–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ask A. Development of resistance to hydroxyurea during treatment of human myelogenous leukemia K562 cells with alpha-difluoromethylornithine as a result of coamplification of genes for ornithine decarboxylase and ribonucleotide reductase R2 subunit. Cancer research. 1993;53(21):5262–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin ZP. Stable suppression of the R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase by R2-targeted short interference RNA sensitizes p53(−/−) HCT-116 colon cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents and ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279(26):27030–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reijns MA. Enzymatic removal of ribonucleotides from DNA is essential for mammalian genome integrity and development. Cell. 2012;149(5):1008–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen Y. Mispaired rNMPs in DNA are mutagenic and are targets of mismatch repair and RNases H. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19(1):98–104. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka H. A ribonucleotide reductase gene involved in a p53-dependent cell-cycle checkpoint for DNA damage. Nature. 2000;404(6773):42–9. doi: 10.1038/35003506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]