Abstract

The catalytic (C) subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase [protein kinase A (PKA)] is a major target of cAMP signaling, and its regulation is of fundamental importance to biological processes. One mode of regulation is N-myristylation, which has eluded structural and functional characterization so far because most crystal structures are of the non-myristylated enzyme, are phosphorylated on Ser10, and generally lack electron density for the first 13 residues. We crystallized myristylated wild-type (WT) PKA and a K7C mutant as binary (bound to a substrate peptide) and ternary [bound to a substrate peptide and adenosine-5′-(β,γ-imido)triphosphate] complexes. There was clear electron density for the entire N-terminus in the binary complexes, both refined to 2.0 Å, and K7C ternary complex, refined to 1.35 Å. The N-termini in these three structures display a novel conformation with a previously unseen helix from residues 1 to 7. The K7C mutant appears to have a more stable N-terminus, and this correlated with a significant decrease in the B-factors for the N-terminus in the myr-K7C complexes compared to the WT binary complex. The N-terminus of the myristylated WT ternary complex, refined to 2.0 Å, was disordered as in previous structures. In addition to a more ordered N-terminus, the myristylated K7C mutant exhibited a 53% increase in kcat. The effect of nucleotide binding on the structure of the N-terminus in the WT protein and the kinetic changes in the K7C protein suggest that myristylation or occupancy of the myristyl binding pocket may serve as a site for allosteric regulation in the C-subunit.

Keywords: crystal structure, protein kinase A, N-myristylation (N-myristoylation), multiple conformations, stabilize

Introduction

cAMP-dependent protein kinase [protein kinase A (PKA)] is a Ser/Thr phosphoryl transferase that consists of two catalytic (C) subunit monomers that phosphorylate target substrates as well as a regulatory (R) subunit dimer that binds to and inactivates the C-subunit.1 PKA is regulated by the second messenger, cAMP, which binds to the R-subunit dimer causing a conformational change that allows for the release of the active C-subunit monomers.1 There are four isoforms of the regulatory subunit: RIα, RIβ, RIIα, and RIIβ. These R-subunit isoforms serve nonredundant functions, and RIα and RIIα are ubiquitously expressed while RIβ and RIIβ exhibit tissue-specific expression.2,3 The RI subunits are thought to typically be cytosolic while RII subunits are generally localized to specific regions within the cell via A-kinase anchoring proteins. However, RI subunits can also be localized by A-kinase anchoring proteins.2,3 Therefore, there are specific mechanisms to localize and regulate PKA activity.

The catalytic subunit of PKA performs the phosphotransfer reaction, and it is well characterized structurally and biochemically.4–7 The C-subunit of PKA was the first protein kinase structure solved,8 and there are many structures of the enzyme in multiple states including apo,9,10 bound to a peptide (binary complex),8,11–13 and bound to a peptide and ATP (ternary complex).14–16 The C-subunit of PKA serves as an important model for the kinase family because the core of the C-subunit (residues 40–300) is conserved throughout the protein kinase superfamily, whereas the C-terminus (residues 301–350) is a distinguishing feature of the AGC group of protein kinases. In contrast, the N-terminus of the C-subunit (residues 1–39) is not found in other kinases and is variable even within different PKA isoforms. The N-terminus of PKA is largely composed of one helix termed the A-helix, which is a site for protein interactions. A-kinase-interacting protein (AKIP) binds to the N-terminus between residues 15 and 30 and acts to localize PKA to the nucleus.17 Additionally, the N-terminus is a site of many potential modes of co- and posttranslational regulation via different modifications including myristylation of the N-terminal glycine, deamidation of Asn2, and phosphorylation of Ser10, any or all of which may influence PKA interactions, activity, or localization.18

Myristylation is the irreversible, covalent attachment of the 14-carbon saturated fatty acid, myristic acid, onto the N-terminal glycine of target proteins that typically occurs cotranslationally via N-myristyl transferase (NMT).19 Many signaling and viral proteins are myristylated, and myristylation is important for membrane binding and proper localization of many proteins.20,21 However, myristylation has many other roles beyond membrane binding. For example, myristylation is important for the autoinhibition of c-Abelson (c-Abl) tyrosine kinase by stabilizing the autoinhibited state of the protein.22,23 Additionally, myristylation enhances c-Src kinase activity and may be involved in proper ubiquitination and degradation of the protein.24 Also, proteins such as recoverin undergo myristyl-switch mechanisms where binding to Ca2+ influences the location and effect of myristylation on the protein.25–27 With respect to PKA, N-myristylation enhances the thermal stability of the enzyme28,29 and the myristylated C-subunit has a higher affinity for membranes alone; however, association with membranes is further enhanced in RII but not in RI holoenzyme complexes.30

In addition to N-myristylation, the C-subunit of PKA may be regulated by irreversible deamidation of Asn2. Deamidation is a process that is thought to occur non-enzymatically where asparagine or aspartate residues can cyclize with the backbone amide forming a succinimide intermediate and can then be deamidated to form aspartate or iso-aspartate.31 Although this modification is generally thought to occur non-enzymatically, there are some virulence factors that catalyze deamidation of proteins to evade immune response.32,33 The deamidation of residues to iso-aspartate can be reversed by the enzyme L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase, which converts the residue back to aspartate.31 However, if the residue was originally asparagine, then it is permanently changed to aspartate. Additionally, proteins that contain aspartate at residue 2 are not typically myristylated and, indeed, PKA cannot be myristylated if Asn2 is mutated to Asp.34 Therefore, deamidation is a mechanism where aspartate can be present at residue 2 within a myristylated protein. With PKA that is purified from tissues, irreversible deamidation of Asn2 to Asp or isoAsp occurs in about 1/3 of the total C-subunit protein. Also, the deamidated form of the protein has a higher cytosolic-to-nuclear ratio than the non-deamidated protein.35 Thus, deamidation may influence protein localization, and this influence could be attributed to effects from myristylation. For instance, it is possible that the added negative charge at the N-terminus in the deamidated protein may remove myristic acid from its binding pocket, allowing the myristate group to interact with membranes or other binding partners and retain cytosolic localization.

The N-terminus of the C-subunit may also be regulated by phosphorylation of Ser10. Phosphorylation of Ser10 has not been observed from PKA purified from tissues,35 which suggests that it may be a transient phosphorylation event. However, when the C-subunit is expressed in Escherichia coli, most of the protein is autophosphorylated on Ser10.36 Furthermore, PKA purified from tissues can autophosphorylate at Ser10 but only if the protein is deamidated at Asn2.37 This fact suggests the possibility of Ser10 phosphorylation and Asn2 deamidation acting synergistically to add negative charges at the N-terminus, which may prevent membrane binding. Furthermore, NMR studies were recently performed on the myristylated C-subunit, which suggested that Ser10 phosphorylation destabilizes the N-terminus of PKA and causes the myristyl moiety to be removed from its hydrophobic pocket.29 The authors argue that removal of the myristic acid group following Ser10 phosphorylation may improve the capacity for PKA to bind to membranes. Additionally, removing myristic acid from the hydrophobic pocket may also improve the ability for PKA to bind protein partners such as AKIP via the A-helix.

In addition to the potential role of N-myristylation and other N-terminal modifications regulating C-subunit localization and interactions, it is also possible that myristylation can influence the active site of the enzyme. Although C-subunit activity is not altered by myristylation, there is some evidence of a potential influence of myristylation on the active site of the enzyme. First of all, recent NMR studies of the myristylated protein identified chemical shifts near the active site of the enzyme with the myristylated protein.29 Additionally, NMR studies performed in the presence and absence of nucleotide and peptide provide further evidence of a potential cross talk between the myristic acid binding pocket and the active site of the enzyme. These studies identified Trp302, which is in the myristate pocket, as a sensor for binding of both nucleotide and peptide. It exhibits a large chemical shift upon binding to adenosine-5′-(β,γ-imido)triphosphate (AMP-PNP) and protein kinase inhibitor residues 5-24 (IP20).38 This finding provides further evidence that the myristate pocket and the active site could influence each other. Trp302 is especially significant because it lies at the junction of the C-lobe in the kinase core and the beginning of the C-terminal tail. The position of this C-terminal tail is highly conserved in all AGC kinases as is Trp302. Therefore, myristylation of the C-subunit may regulate PKA activity or substrate binding in addition to potential roles in localization.

In this study, we were interested in further elucidating the role of N-myristylation on the structure and regulation of the C-subunit. Structural information about myristylation of PKA is lacking because currently reported structures of the myristylated C-subunit display only part of the N-terminus and the myristic acid group11,14 or are at relatively low resolution with poor density at the N-terminus.12 Using X-ray crystallography and kinetics, we investigated the role of N-myristylation on the structure and function of the C-subunit. We obtained crystal structures of binary and ternary complexes of the wild-type (WT) enzyme and a K7C mutant that exhibited altered kinetics in a myristylated state. We identified a novel conformation of PKA and suggest that the myristic acid binding pocket may be an allosteric regulator of PKA.

Results

Purification and kinetic characterization of the myristylated C-subunit

One of the difficulties of studying the myristylated C-subunit in vitro is that bacterial expression of the acylated C-subunit yields a heterogeneous mixture of phosphorylation/myristylation states. One mutation, K7C, initially generated for fluorescent labeling studies, provided several advantages for studying the effects of N-terminal myristylation. This mutation eliminates the PKA recognition sequence at Ser10 and therefore blocks autophosphorylation of Ser10, which minimizes the total number of phosphorylation isoforms of the C-subunit. More importantly, eliminating Ser10 phosphorylation increased the total yield of myristylated protein (Fig. S1) because we found that myristylation and Ser10 phosphorylation typically do not occur together in our bacterial coexpression system, which was also observed previously with the recombinant myristylated protein.36 The K7C mutation also appears to decrease the mobility of the N-terminus based on time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy (data to be published separately), which helped to structurally characterize the effects of N-myristylation in crystals.

Additionally, we measured the steady-state kinetics of the WT and K7C proteins in myristylated and non-myristylated states. Myristylation of the WT protein does not alter the kinetics. However, the K7C mutant exhibited modest changes in kinetics including increased kcat and Km values compared to the WT C-subunit when myristylated (Table 1). Increased activity of the myr-K7C protein was also verified using rapid quench pre-steady-state kinase assay39 with radiolabeled [γ-32P]ATP experiments, which yielded a similar 55% increase in steady-state rate with no effect on phosphotransfer rate (Fig. S2). The increased kcat also appears specific to the cysteine mutation as several other mutations of this residue including K7A and K7S did not yield this increase (data not shown).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of myristylated and non-myristylated WT and K7C proteins

| Km (μM) kemptide | Km (μM) ATP | kcat (s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 29 ±5 | 19 ±3 | 19±2 |

| Myr-WT | 23 ±2 | 23 ±2 | 18 ±3 |

| K7C | 27 ±2 | 23 ±7 | 18 ±3 |

| Myr-K7C | 43 ±9 | 32 ±7 | 29 ±2 |

Values represent mean±SD from three separate protein preparations that were each measured in triplicate.

Myristylated WT ternary structure (AMP-PNP, Mg2+, and SP20)

We were interested in obtaining crystal structures of the ternary myristylated WT and K7C C-subunits in hopes of further elucidating how myristylation affects the structure and activity of the C-subunit. To further understand substrate binding rather than inhibitor binding, we utilized the peptide, SP20, which corresponds to the minimal 20 residues in PKI (5–24) that are necessary for inhibition of the C-subunit with two mutations (N20A and A21S) that convert this peptide from an inhibitor to a substrate.13 We solved the crystal structure of the myristylated WT ternary complex to 2.0 Å resolution, but we obtained very little novel information compared to the older ternary structure obtained by Bossemeyer et al.14 Like the previous structure, only part of the N-terminus and myristic acid are visible in the electron density. The density for the N-terminus begins at Ser10, and although the entire myristic acid group was included in the structure, the electron density is strong for only part of the myristic acid group (Fig. S3).

Myristylated K7C ternary structure

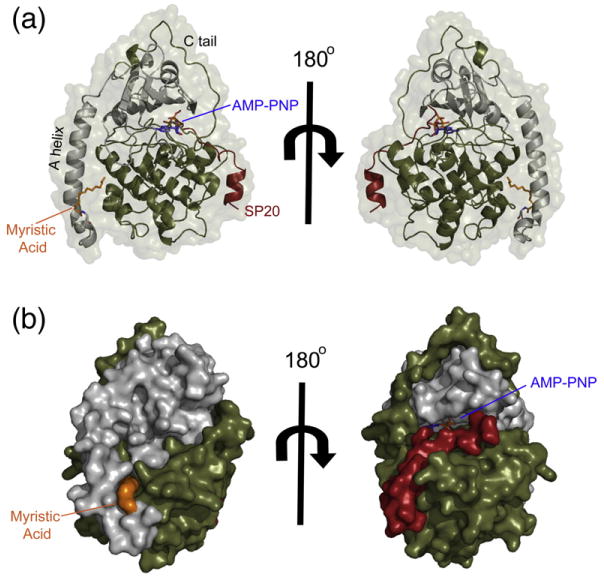

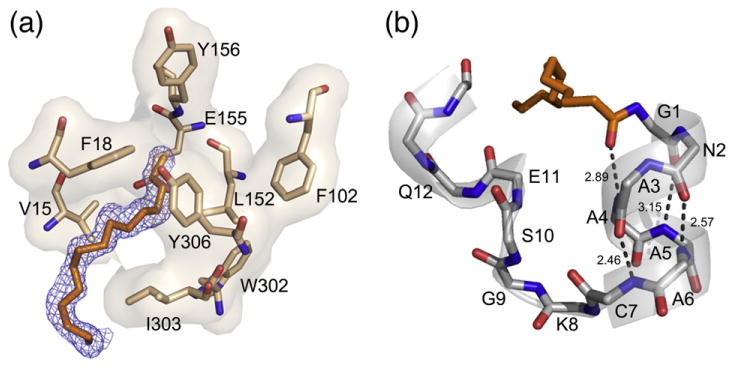

In contrast to the structure of the myr-WT C-subunit, the ternary complex of myr-K7C displays a well-ordered N-terminus. The structure of the ternary myristylated K7C complex was solved to 1.35 Å resolution, which is one of the highest-resolution PKA structures reported. This structure reveals a novel conformation (Fig. 1a and b) with the entire N-terminus and myristic acid visible in the electron density (Fig. 3). The myristyl moiety binds within its previously defined hydrophobic pocket, but for the first time, there is strong electron density for each atom of the myristic acid (Fig. 2a). The N-terminus adopts a new conformation in which the A-helix ends at Ser10 and is preceded by a small loop from Ser10 to Cys7. A new helix is formed from Cys7 through the myristic acid group, which is also part of the helix with its carbonyl oxygen hydrogen bonding with the backbone amide of Ala4 (Fig. 2b). Specifically, the carbonyl oxygen caps the N-terminus of the helix. To our knowledge, this is the first instance of myristic acid being part of a protein's secondary structure.

Fig. 1.

The overall myristylated K7C ternary structure that displays the entire N-terminus in a novel conformation. (a) The overall structure of the myristylated K7C ternary complex is shown in cartoon representation with the small lobe colored gray, large lobe colored olive, SP20 colored red, AMP-PNP colored blue, and myristic acid colored orange. The protein surface is shown in transparent representation. This is the first time that the entire N-terminus and myristic acid are visible in a ternary complex and displays a novel α-helix from residues 1 to 7, unlike the WT ternary complex (see also Fig. S3). (b) The K7C ternary complex is shown as a surface representation with same color scheme as in (a). The surface representation highlights the myristic acid binding pocket as well as the platform created by the novel N-terminal helix.

Fig. 3.

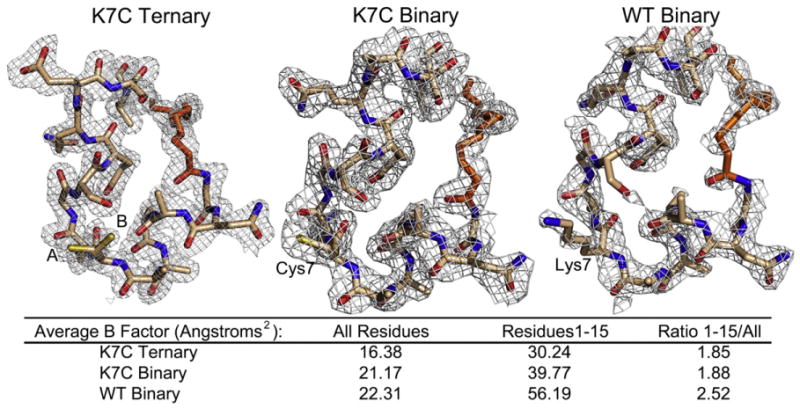

Electron density of the N-termini for the structures displaying the entire N-terminus and myristic acid. The 2Fo– Fc electron density maps contoured to 1 σ are shown for the first 15 residues and myristic acid for the myristylated K7C ternary, K7C binary, and WT binary structures. Residue 7 is annotated in each structure, and the K7C ternary structure adopts two conformations, A (65%) and B (35%). There is strong electron density for each structure at the N-terminus. However, the electron density for the WT binary structure is not as good with density lacking at some regions including part of the myristic acid and the Ser10 side chain. This is also reflected by the average B-factors for all residues compared to residues 1–15 for each structure that are listed in the figure.

Fig. 2.

The myristic acid binding pocket and N-terminal helix. (a) The location of the myristic acid and interacting residues within its binding pocket are shown in stick representation with the 2Fo–Fc electron density map at 1 σ displayed for myristic acid in blue. (b) The myristic acid and main-chain atoms of the novel helix are shown in stick representation with H-bonding distances shown to highlight the properties of the helix.

Structures of myristylated WT and K7C proteins in binary complex with SP20

Binary complexes were also crystallized in hopes that they might yield further insights into the role of myristylation in the catalytic cycle of PKA. Both myristylated WT and K7C proteins bound to the SP20 peptide were crystallized and the structures were refined to 2.0 Å resolution. Both binary structures, like the K7C ternary structure, have completely resolved N-termini. The entire N-terminus and myristic acid are visible in the electron density (Fig. 3) and display the same conformation that was seen with the K7C ternary structure. Again, the A-helix ends at Ser10 and both binary structures display the novel helix from residues 1 to 7.

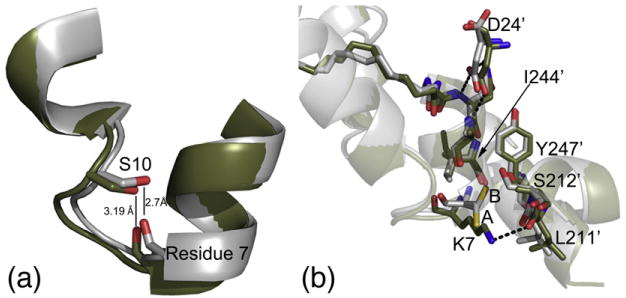

The fact that the myr-WT protein displays this conformation suggests that the conformation is not an artifact of the mutation, and it allows us to make conclusions about why the myr-K7C protein retains this conformation in a ternary complex. Alignment of the myr-K7C and myr-WT binary structures reveals one possible explanation for stabilization of this conformation with the K7C protein. The distance between the Ser10 side chain and backbone carbonyl of residue 7 is around 2.7 Å in the K7C structure compared to around 3.1 Å in the WT structure (Fig. 4a). Therefore, the mutation possibly stabilizes this hydrogen bond, which may help in the ordering of the N-terminus. Further evidence that the N-terminus is more stable in the myr-K7C protein than in the WT protein is evident from the electron density and B-factors of the binary structures. Although the binary K7C and WT structures were refined to the same resolution, the electron density is better at the N-terminus for the K7C structure than for the WT structure (Fig. 3). Also, the B-factors at the N-terminus are greater for the WT structure (56 Å2) than for the K7C structure (40 Å2) despite similar overall B-values (∼20 Å2) for both enzymes, which further suggests that the N-terminus is more stable in the mutant (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Potential roles of the K7C mutation in the stabilization of the N-terminus. (a) The K7C (gray) and WT (olive) binary structures are aligned with the backbone atoms of residue 7 and side chain of Ser10 shown in stick representation. The distance between the Ser10 side chain and the backbone carbonyl of residue 7 is displayed, showing that the atoms are in H-bonding distance in the K7C mutant but not in the WT structure. It is possible that this hydrogen bond could stabilize the N-terminus. (b) K7C ternary and WT binary structures are aligned and colored as in (a); also shown here are the crystal packing interactions with symmetry-related molecules at the N-terminus. The K7C and WT structures adopt similar crystal packing with Ile210, Leu211, and Ser212, which are near the APE motif; Ile244 and Tyr247 from the G-helix; and Asp24 from the SP20 peptide. However, residue 7 and Leu211 from the symmetry-related molecule are slightly shifted in the WT structure possibly to facilitate packing and possibly to form a hydrogen bond between Lys7 and the backbone carbonyl of Leu211. Also, the K7C ternary structure adopts two conformations, A (65%) and B (35%), but the K7C binary structure only has density for conformation A. This B conformation would destabilize this crystal packing with the WT lysine residue.

Crystal contacts in structures with an ordered versus disordered N-terminus

Another difference between the complexes with ordered N-termini (WT binary, K7C binary, and K7C ternary structures) and the WT ternary complex that exhibits a disordered N-terminus is changes in unit cell dimensions. Both conformations crystallized in the same space group. However, the WT ternary complex crystallized with unit cell dimensions of a=57.80 Å, b=78.73 Å, and c=99.00 Å, and the complexes with resolved N-termini crystallized with unit cell dimensions of a=48 Å, b=80 Å, and c=118 Å (Table 2). The WT ternary complex unit cell dimensions are a fairly common crystal form for PKA.15,16,41,42 In contrast, the a=48 Å, b=80 Å, and c=118 Å unit cell dimensions were observed only once previously in 1SMH.43 This previous structure also exhibits a completely resolved N-terminus except that the N-terminus adopts a single α-helix from residues 1 to 31.

Table 2.

Crystallography data collection and refinement statistics

| Myr-WT ternary | Myr-WT binary | Myr-K7C ternary | Myr-K7C binary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | 4DG0 | 4DG2 | 4DFX | 4DFZ |

| Data Collection | ||||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a (Å) | 57.80 | 48.48 | 48.10 | 48.46 |

| b (Å) | 78.73 | 79.63 | 79.70 | 79.63 |

| c (Å) | 99.00 | 117.89 | 117.23 | 118.06 |

| Unique reflections | 31,277 (4494) | 25,942 (3628) | 95,939 (13,243) | 30,558 (4292) |

| Multiplicity | 6.5 (6.5) | 6.2 (6.4) | 5.3 (5.7) | 5.0 (5.2) |

| Resolution range (Å) | 39.37–2.0 (2.11–2.00)a | 39.30–2.00 (2.11–2.00)a | 25.03–1.35 (1.42–1.35)a | 37.46–2.00 (2.11–2.00)a |

| Rsym (%) | 11.4 (38.7) | 7.2 (26.8) | 4.8 (35.9) | 11.7 (54.5) |

| I/σI | 9.5 (4.2) | 16.3 (5.9) | 15.8 (3.9) | 9.3 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 82.6 (80.5) | 96.5 (92.5) | 96.8 (94.7) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Rwork/Rfree(%)b | 19.4/22.7 (22.4/24.6) | 19.2/21.1 (21.4/25.1) | 15.5/17.9 (22.4/25.5) | 20.5/23.4 (26.1/27.3) |

| Ramachandran angles (%)c | ||||

| Favored regions | 98.31 | 98.07 | 98.07 | 98.07 |

| Allowed regions | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| r.m.s.d. | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.952 | 0.866 | 1.34 | 0.887 |

All data collection was performed at the Advanced Light Source laboratory in Berkeley, CA, on beamline 8.2.1.

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest-resolution shell.

Five percent of the data were excluded from the refinement to calculate the Rfree.

Ramachandran plot quality as defined in MolProbity.40

The ordered N-terminus in the myristylated structures forms crystal contacts with Ile210, Leu211, and Ser212, which are near the APE motif, and Ile244 and Tyr247 from the G-helix. Additionally, Asp24 from the SP20 peptide may make hydrogen bonds with the Asn2 side chain and with the backbone nitrogen atoms from Asn2 and Ala3 and could help to stabilize this N-terminal helix (Fig. 4b). 1SMH forms similar crystal contacts except that it does not interact with the PKI peptide and instead forms additional contacts with Glu248 and Val251 with the extended A-helix (Fig. S4a). Additionally, one other PKA structure, 3QAM,16 exhibits similar crystal packing at the N-terminus as 1SMH and these myristylated structures. Although this structure belongs to a different space group, P21, it has similar a and b cell dimensions (a=48 Å, b=80 Å, and c=61 Å) and exhibits similar crystal packing with a symmetry-related molecule at the N-terminus. This structure shows similar interactions as 1SMH and also forms an extended A-helix (Fig. S4a). In contrast to these ordered structures, the WT ternary structure does not make crystal contacts at the N-terminus, which supports the possibility of high level of flexibility of this region within protein crystals. There is a large space near the N-terminus that may allow for flexibility of the region without interfering with crystal packing (Fig. S4b).

Additionally, another aspect to consider is how the K7C mutation may have influenced the crystal packing in these structures. This possibility is especially important because previous reports suggest that mutation of lysine residues to small hydrophobic residues may improve crystallization by decreasing conformational entropy and improving crystal packing.44 Alignment of the K7C structures with the WT binary structures illustrates very similar packing. However, there is one change, which is a difference in the positioning of Lys7 and Leu211, from the symmetry-related molecule, in the WT binary structure compared to Cys7 and Leu211 in the K7C structures. In the WT binary structure, Lys7 is moved down relative to the Cys7 structures by about 1.7 Å, which may be necessary to facilitate packing and possibly to optimize the formation of a hydrogen bond between Lys7 and the backbone carbonyl of Leu211 (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, in the K7C ternary structure, Cys7 adopts two conformations, A modeled with 65% occupancy and B modeled with 35% occupancy, and one of these conformations, termed conformation B, is facing the symmetry-related molecule (Fig. 4b). The K7C binary structure only shows density for conformation A. This B conformation and the potential for increased flexibility of the N-terminus in a ternary structure may partially explain why the WT protein does not adopt this conformation in a ternary complex. If a lysine is present at residue 7, then the B conformation observed in the K7C ternary structure would interfere with this crystal packing.

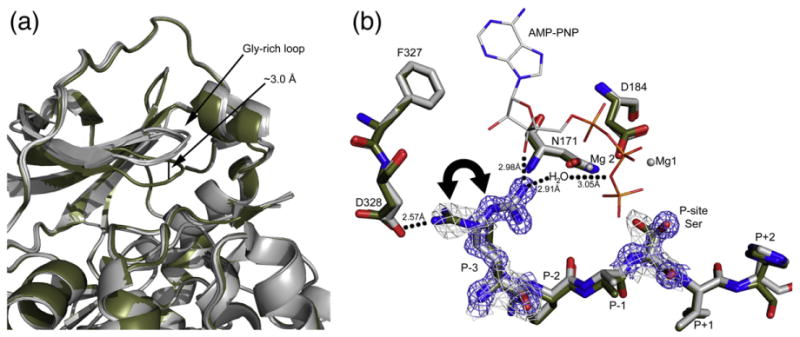

Comparison of myristylated binary and ternary structures

All structures reported here crystallized in a closed conformation except for a slightly raised glycine-rich loop, which was seen in all structures (Fig. 5a). There were not many major differences between the binary and ternary structures, suggesting that the active site and active state of the enzyme can be formed by substrate binding alone. This result was not surprising since other binary structures also crystallized in a closed conformation.13 The majority of residues involved in ATP binding are essentially preformed in the binary complex. One exception is repositioning of the P-site Ser after AMP-PNP binding, and the P-3 Arg repositions from binding Asp328 in the C-tail in a binary complex to coordinate AMP-PNP by potentially hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl group from the 3′ carbon on the ribose and/or via a water molecule in a ternary complex (Fig. 5b). The binary complexes were modeled with one conformation, facing the C-tail, but display some positive density for the P-3 Arg facing the active site and may exhibit some exchange between the two conformations. However, the ternary complex only shows density for the conformation with the P-3 Arg facing the active site. At least one other binary structure, 1APM,45 displays both conformations of the P-3 Arg facing the active site and C-tail.

Fig. 5.

Changes at the active site in the myristylated structures. (a) The four myristylated structures presented here are colored gray and aligned. Also aligned and displayed is another PKA structure, 1RDQ,15 in olive. The myristylated structures adopt a slightly raised glycine-rich loop, about 3 Å, compared to most closed PKA structures. (b) The active-site residues of the myr-K7C binary complex (olive) and myr-K7C ternary complex (gray) are shown. Also displayed is the location of the magnesium ions (gray spheres) and AMP-PNP (stick representation) from the ternary complex. The 2Fo–Fc electron density maps at 1 σ are shown in gray for the binary complex and in blue for the ternary complex for the P-site Ser and P-3 Arg, highlighting the shifts in these residues upon formation of a ternary complex. The P-3 Arg was modeled facing the C-tail in the binary complexes, but there is some positive density for the P-3 Arg facing the active site, and it may exert some exchange between the two conformations. However, the residue only faces the active site in a ternary complex.

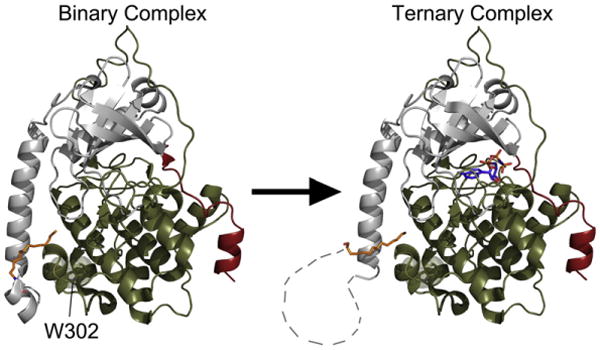

Furthermore, although the myristylated K7C mutant retains an ordered N-terminus in both a binary and a ternary complex, the myr-WT protein apparently undergoes a disordering of its N-terminus upon formation of a ternary complex (Fig. 6). This result suggests that the formation of a ternary complex and catalysis by PKA may cause long-range dynamic effects throughout the enzyme, which causes the N-terminus to become disordered. Also, with no other major differences between the myr-WT and myr-K7C proteins, it is possible that the altered kinetics observed with myr-K7C may be due to its ability to retain an ordered N-terminus with myristic acid bound within its hydrophobic pocket in a ternary complex.

Fig. 6.

The formation of a ternary complex produces dynamic movements within the C-subunit that causes a disordering of the N-terminus. The C-subunit of PKA is shown in cartoon representation with the small lobe colored gray, large lobe colored olive, SP20 colored red, myristic acid colored orange, and AMP-PNP colored blue. The WT binary complex has a completely ordered N-terminus, which is displayed on the left, but upon formation of a ternary complex, the N-terminus of the WT C-subunit becomes disordered as illustrated on the right. The disordered regions of the N-terminus are displayed as connecting lines. Also, highlighted is Trp302, which is thought to be a sensor of active-site occupancy38 and may support the link between nucleotide binding and the conformation of the N-terminus.

Discussion

Acylation adds potential modes of protein regulation, and in the case of myristylation, the acyl moiety is added cotranslationally and, thus, the modification is carried throughout the lifetime of the protein. Having established previously that the N-terminal myristylation site in the PKA C-subunit serves as a “switch” that can be mobilized in type II holoenzymes to associate with membranes,30 here we show how the N-myristylated N-terminus can be docked to the kinase core where it may influence the active site of the enzyme. We identify a new conformation of the N-terminus that is present in the WT binary complex and appears to be stabilized by a K7C mutation that allows the protein to retain this conformation in a ternary complex. Since this conformation was seen in the WT protein when a high-affinity peptide was bound, we believe that this reflects a true physiological state of the protein.

Myristylation of the C-subunit is important for the structural stability of the enzyme as evident by an increase in thermostability with myristylated compared to non-myristylated PKA,28,29 and structural stabilization with myristylation may be a general trend for many proteins.46 The results presented here provide a structural basis for the stabilizing effect of myristylation on PKA. Myristylation results in a completely ordered N-terminus in the binary complexes of both the mutant and WT C-subunit structures and in the K7C ternary structure, which is not typically observed in PKA structures. Also, binding of myristic acid to the hydrophobic pocket may stabilize the A-helix that spans both lobes of the kinase (Fig. 1a) and could therefore stabilize the entire protein. Additionally, the myristic acid group interacts directly with the core of the protein, which may provide structural stability.

Although myristic acid is present within its hydrophobic pocket in all four structures, the WT C-subunit shows density for only part of the N-terminus and myristic acid in the ternary complex (Fig. S3), but the K7C mutant C-subunit retains an ordered N-terminus in a ternary complex. The stabilization of this conformation in the K7C protein may be attributed to a hydrogen bond between the side chain hydroxyl group of Ser10 and backbone carbonyl oxygen of Cys7 that are in hydrogen bonding distance in the K7C structures but not in the WT structure (Fig. 4a). It may also be due to enhanced crystal packing with the K7C mutant that may allow this conformation to exist in a crystal lattice even with a more flexible N-terminus, which cannot occur with the WT lysine at residue7 (Fig. 4b). Because both WT and K7C C-subunits form a stable helix at the N-terminus in a binary complex, this conformation is relevant to the WT enzyme and provides several possibilities with regard to other N-terminal modifications.

First of all, the structures with the ordered N-termini suggest functional roles for the other N-terminal modifications including Ser10 phosphorylation and Asn2 deamidation. In the structures with ordered N-termini, the Ser10 side-chain hy-droxyl group is around 4.0 Å or less distance away from the backbone carbonyl of Lys7, the backbone carbonyl of Ala3, the Cα of Ala3, and the Cα of Ala4. Therefore, phosphorylation of Ser10 would almost certainly destabilize this conformation. Based on NMR studies, Gaffarogullari et al. suggested that Ser10 phosphorylation may remove myristic acid from the myristate pocket, which could increase membrane binding of the enzyme.29 Phosphorylation of Ser10 may also make the A-helix more mobile, which may enhance protein–protein interactions via the A-helix with other proteins such as AKIP.17 Furthermore, Asn2 deamidation may exhibit a similar destabilizing effect on the N-terminus because of the added negative charge near the myristic acid group. Also, because the deamidated form of PKA can autophosphorylate on Ser10,37 these two modifications may act synergistically to prevent membrane binding of the enzyme by adding negative charges at the N-terminus. These structures suggest interplay between N-myristylation and other N-terminal modifications, which are likely to have biological significance.

In addition, these structures reveal a role of ATP binding on the structure of the N-terminus. With the WT protein, the ordered N-terminus in the binary complex (bound only to SP20) becomes disordered in the ternary complex with the addition of AMP-PNP binding (Fig. 6). This cross talk is interesting considering that the N-terminus or myristic acid and the ATP binding site are 20–30 Å apart, suggesting allosteric networks throughout the enzyme. This possibility is further exemplified by c-Abl, which is affected by small molecules binding within its myristic acid binding pocket. Abl can be either inhibited 7,4 or activated in response to small-molecule binding within its myristate pocket. The location of the myristate pockets in c-Abl versus PKA differs. The myristic acid group in c-Abl binds in the hydrophobic core of the large lobe between the E-and F-helices. In PKA, the myristate pocket is formed between the A-, J-, and E-helices near the surface of the protein. Despite different locations of the myristate pockets, the findings presented here offer evidence that the myristic acid binding site may influence the active site or enzyme activity of PKA. This idea is further supported by the increased kcat and Km values exhibited by the myristylated K7C protein, which only differed in structure from the WT protein with its ordered N-terminus, suggesting that myristylation has the potential to influence catalytic activity.

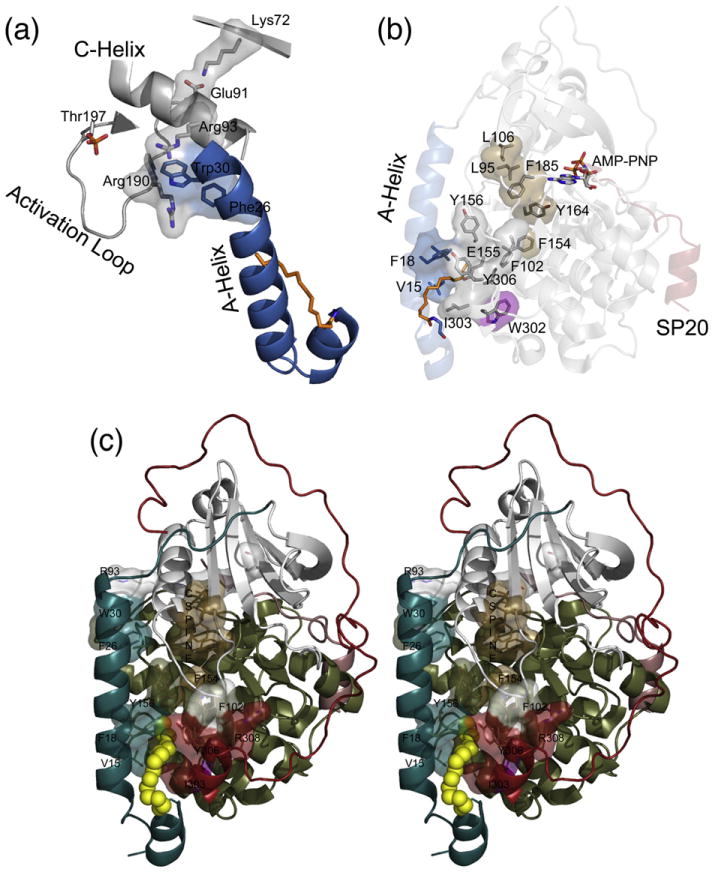

An examination of interactions of the A-helix and the myristic acid binding pocket with the enzyme provides possible reasons why myristylation may influence the active site of the enzyme. First of all, one of the most important features for an active kinase is an interaction between Glu91 from the C-helix and Lys72 from the β3 strand.50 Lys72 binds to the α and β phosphate of ATP and is positioned by Glu91. The A-helix may influence the C-helix, and therefore Glu91, because Trp30 from the A-helix is packed against Arg93 from the C-helix, and if myristylation influences A-helix dynamics or interactions, it could influence the important K72–E91 interaction and possibly influence ATP binding (Fig. 7a and c). Furthermore, the same Trp30 interacts with the activation loop, which is a critical component for PKA activity.51 Trp30 is near Arg190 from the activation loop and may also impact this region of the protein when myristylated. Therefore, these A-helix interactions may be altered by myristylation, which, in turn, may influence the active site.

Fig. 7.

Interactions of the myristic acid group and the A-helix within the C-subunit could influence the active site. (a) The A-helix is colored blue, myristic acid is colored orange, and other elements are colored gray. The A-helix residues Trp30 and Phe26 may interact with Arg93 and Arg190, which may influence the C-helix and the important Lys72–Glu91 interaction or the activation loop, respectively. (b) The A-helix is colored blue, myristic acid is colored orange, small lobe is colored gray, large lobe is colored olive, and SP20 is colored red. The protein is shown in transparent cartoon representation with specific residues highlighted in stick and surface representation. Residues in or near the myristate pocket may influence the active site such as Phe154 that is directly opposite of the myristate pocket and may influence the C-spine;50 residues Y164, F185, L95, and L106, which are colored brown; and the active site of the enzyme. Also, W302, highlighted in purple, is known to be a sensor of active-site occupancy38 and suggests potential cross-talk between the myristate pocket and active site. (c) A stereo view of the myristic acid pocket and interacting residues is displayed. In this depiction, the myristylated K7C binary structure is shown in cartoon representation with the N-terminus (residues 1–40) colored teal, the small lobe (residues 41–126) colored gray, the large lobe (residues 127–300) colored olive, the C-tail (residues 301–350) colored red, the myristic acid colored yellow and depicted in sphere representation, and the C-spine residues colored brown.

Additionally, it is possible that the myristic acid group may influence the active site or enzyme activity via interactions that are known to be important for activity of PKA and all kinases. Comparison of many eukaryotic and prokaryotic kinases identified a hydrophobic “spine” that is thought to be important for kinase activity and is composed of Leu95, Leu106, Tyr164, and Phe185, with numbering based on PKA.50 Although the myristic acid group and residues within its hydrophobic pocket do not directly interact with the catalytic spine, it is possible that it can influence these elements via residues surrounding the myristic acid pocket. For example, Phe154, which is directly opposite of the myristate pocket in the E-helix (Fig. 7b and c), interacts with Tyr164 that is part of the hydrophobic spine, and if myristylation influences Phe154 and the catalytic spine, then it could influence magnesium binding, ATP binding, or the active site and enzyme activity in general. Additionally, Trp302 is part of the myristic acid binding pocket (Figs. 2a and 7b), and although very distant from the active site, it exhibits very large chemical shifts following peptide and AMP-PNP binding based on NMR studies.38 Therefore, this residue provides further evidence of cross-talk between the active site and the myristate pocket.

Occupation of the myristate pocket may increase the dynamics at the active site. This possibility could explain why the myr-K7C protein had increased kcat but also increased Km values. The enzyme efficiency (kcat/Km) is essentially unchanged with the myr-K7C protein, and this may be due to a faster ADP off-rate, the rate limiting step for activity,52 and lower affinity for substrates. This possibility may suggest increased dynamics at the active site and may explain the slightly raised Gly-rich loop observed in these myristylated structures (Fig. 5a). Therefore, although the kinetics of the WT protein is not influenced by myristylation, it is possible that different binding partners or ligands may influence the active site or enzyme activity by binding to the N-terminus. For instance, AKIP or other N-terminal binding partners may keep myristic acid within its binding pocket to influence PKA activity. Additionally, other lipids or ligands may alter the activity of PKA by utilizing this allosteric site. Like c-Abl, the myristate pocket of PKA may be a potential site for small-molecule activators or inhibitors. Indeed, a recent study of Cα2, which is not myristylated but retains the hydrophobic myristate pocket, exhibited small but not significant increases in enzyme activity in the presence of excess fatty acid.53 Perhaps specific lipids, ligands, or protein interactions can enhance this effect on PKA activity. In general, these structures suggest that, in addition to potential roles in localization, myristylation may serve additional regulatory roles on active-site dynamics, substrate binding, or enzyme activity when bound into the hydrophobic pocket.

Materials and Methods

Purification of the myristylated C-subunit proteins

The non-myristylated WT and K7C C-subunits were expressed and purified as described previously.54 The myristylated C-subunit was prepared by coexpression with yeast NMT as described previously55 and purified following a method described previously.56 Cultures of NMT/PKA were grown at 37 °C to an OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of ∼0.6 and induced with 1.0 mM IPTG and 0.26 mM sodium myristate. The cultures were grown for 18–24 h at 24 °C before being harvested. The PKA/NMT pellet and a H6-tagged RIIα(R213K) pellet corresponding to at least a third of the culture volume of the PKA/NMT pellet [i.e., 12 L PKA/NMT: 4 L H6-RIIα(R213K)] was resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM imidazole, 150 mM KCl, 200 μM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.5]. The resuspended pellets were then lysed using a microfluidizer (microfluidics) at 18,000 psi. The cells were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C for 60 min in a Beckman JA20 rotor, and the supernatant was incubated with ProBond Resin (Invitrogen) for 24 h at 4 °C. The resin was loaded onto a column and washed twice with the lysis buffer. Three 10-mL elutions were then collected using 1 mM cAMP dissolved in lysis buffer. The elutions were combined and dialyzed overnight into 20 mM KH2PO4, 25 mM KCl, and 5 mM DTT, pH 6.5, and then loaded onto a pre-packed Mono-S 10/100 (GE Healthcare) cation-exchange column equilibrated in the same buffer. The protein was eluted from the column with a KCl gradient ranging from 0 to 1 M. The myristylation state of the protein was confirmed using mass spectrometry. The myristylated protein eluted from the MonoS at a higher KCl concentration than the non-myristylated protein, allowing for effective separation of non-myristylated from myristylated protein. Also, the majority of the protein was myristylated (around 75% for WT and ∼100% for K7C) (Fig. S1 and Table S1).

Crystallization

Myristylated WT and myristylated K7C ternary (AMP-PNP, Mg2+, SP20) and binary (SP20) complexes were crystallized under very similar conditions utilized for previous C-subunit structures.10,15 In each case, the protein being crystallized was dialyzed overnight into 50 mM N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine, 150 mM ammonium acetate, and 10 mM DTT, pH 8.0. Then, the protein was concentrated to 8–10 mg/mL. The proteins were set up for crystallization using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 4 °C. Immediately preceding the crystal tray preparation, the protein was combined in 1:10:20:5 molar ratio of protein:AMP-PNP:Mg2+:SP20 for the ternary complex or 1:5 protein:SP20 for the binary complex. These complexes were screened under different 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) concentrations ranging from 2% to 18% and with different buffer conditions in the mother liquor including no buffer in the mother liquor or buffers ranging from pH 5.35 to pH 8.5. The drop contained 1:1 volume of protein solution:well solution, and 9–13% methanol was added to the well solution before sealing the well. For the ternary complexes, crystals were typically seen after 1–2 weeks and generally appeared to reach maximum size by 4–6 weeks, and with the binary complexes, crystals appeared after 4–6 weeks and reached maximum size by 8–10 weeks. The myristylated WT C-subunit ternary structure was obtained from a crystal grown with a well solution containing 10% MPD and 9% MeOH added to the well. The myristylated K7C ternary structure was obtained from a crystal grown with a well containing 12% MPD, 100 mM 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl) propane-1,3-diol, pH 6.5, and 9% MeOH added to the well. The myristylated WT and K7C binary structures were obtained from crystals grown with wells containing 6% MPD and 9% MeOH added to the well solution. The WT and K7C binary complexes were crystallized from protein samples with two phosphates on Thr197 and Ser338. The WT and K7C ternary complexes were crystallized from a protein mixture containing two or three phosphates with phosphates being on Thr197 and Ser338 for all proteins and some proteins with phosphate on Ser139. The WT and K7C ternary structures were both modeled with 40% phosphorylation of Ser139.

Data collection and refinement

The crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen with cryoprotectant solution (16% MPD and 15% glycerol). Data were collected on the synchrotron beamline 8.2.1 of the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Labs (Berkeley, CA). For each crystal structure, the data were integrated using iMOSFLM.57 All protein variants and complexes crystallized in the P212121 space group similar to the WT structure. Molecular replacement was carried out using Phaser58 with a previously solved C-subunit structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 3FJQ42] as a search model. The refinement was performed using refmac559 and model building was done in Coot.60 With the binary complexes and ternary K7C complex, positive density was readily apparent at the N-terminus of the protein. The myristylated ternary K7C structure had the clearest density at the N-terminus due to its high resolution, and the N-terminus and myristic acid were modeled into this density. Then, the conformation seen with the K7C ternary complex was modeled into the binary complexes and also fit the density for these proteins very well with only slight changes necessary. The myristylated WT ternary structure, myristylated K7C ternary structure, myristylated WT binary structure, and myristylated K7C binary structure were refined to Rwork/Rfree values of 19.4%/22.7%, 15.5%/17.9%, 19.2%/21.1%, and 20.5%/23.4%, respectively. The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 2.

Steady-state kinetics

The kinetics were performed as described previously.61,62 Reactions were performed in 100 mM Mops (pH 7.0) and 10 mM MgCl2. The concentration of kemptide (LRRASLG) was fixed at 250 μM and ATP was varied from 10 to 500 μM to measure the Km for ATP. The concentration of ATP was fixed at 1 mM and kemptide was varied from 10 to 300 μM to measure the Km for kemptide. The final concentration of enzyme was ∼0.003 mg/mL. Three separate protein preparations of each C-subunit isoform were measured. All measurements were done in triplicate. Data were fit using GraphPad Prism.

Mass spectrometry analysis of myristylated proteins

Proteins (5 μg each) were dissolved in 14% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and separated using Magic 2002 HPLC system (Michrom BioResources, Inc.) and eluted into an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) using electrospray ionization. The HPLC gradient was 14–100% Buffer B in 10 min (Buffer A: 2% acetonitrile and 0.05% TFA; Buffer B: 90% acetonitrile and 0.04% TFA). The flow rate was 10 μL/min. The LTQ-Orbitrap was set to scan from 400 to 2000 (MS only) with a resolution of 100,000 in positive, profile mode. The raw data were deconvoluted using Xtract to obtain the intact protein molecular weight.

Rapid quench flow experiments

Pre-steady-state kinetic measurements of the myr-K7C versus non-myristylated WT protein were performed using rapid quench flow apparatus (Model RGF-3) from KinTek Corp., following previously described procedures.39,51 Experiments were performed with 200 μM ATP and 2 mM kemptide. The activity of [γ-32P]ATP was (5000–15,000 cpm/pmol). The reaction was carried in 100 mM Mops (pH 7.4), 10 mM Mg2+, and 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. The reaction was quenched using 30% acetic acid.

PDB coordinates

The structure factors and coordinates for the following structures are deposited in the PDB: K7C ternary (PDB ID: 4DFX), K7C binary (PDB ID: 4DFZ), WT ternary (PDB ID: 4DG0), and WT binary (PDB ID: 4DG2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (GM19301 to S.S.T and F31GM099415 to A.C.B.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the NIH. Additionally, Adam C. Bastidas was funded by the Ford Foundation Diversity Fellowship. Additional support was provided to A.C.B. by the University of California San Diego Graduate Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology through an institutional training grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, T32 GM007752 (J.M.S.), and through support by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award NIH/National Cancer Institute T32 CA009523 to J.M.S. We would also like to thank Ganapathy Sarma and Jian Wu for helpful discussions, and we would like to thank Joe Adams for use of the rapid quench flow apparatus.

Abbreviations

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKI

protein kinase inhibitor

- MPD

2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol

- AMP-PNP

adenosine-5′-(β,γ-imido)triphosphate

- WT

wild type

- AKIP

A-kinase-interacting protein

- NMT

N-myristyl transferase

- c-Abl

c-Abelson

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

Edited by C. Kalodimos

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.021

References

- 1.Taylor SS, Kim C, Cheng CY, Brown SH, Wu J, Kannan N. Signaling through cAMP and cAMP-dependent protein kinase: diverse strategies for drug design. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirschner LS, Yin Z, Jones GN, Mahoney E. Mouse models of altered protein kinase A signaling. Endocr-Relat Cancer. 2009;16:773–793. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mucignat-Caretta C, Caretta A. Clustered distribution of cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory isoform RI alpha during the development of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2002;451:324–333. doi: 10.1002/cne.10352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis SH, Corbin JD. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:237–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tasken K, Skalhegg BS, Tasken KA, Solberg R, Knutsen HK, Levy FO, et al. Structure, function, and regulation of human cAMP-dependent protein kinases. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1997;31:191–204. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(97)80019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shabb JB. Physiological substrates of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2381–2411. doi: 10.1021/cr000236l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson DA, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knighton DR, Zheng JH, Ten Eyck LF, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Structure of a peptide inhibitor bound to the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1991;253:414–420. doi: 10.1126/science.1862343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akamine P, Madhusudan, Wu J, Xuong NH, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS. Dynamic features of cAMP-dependent protein kinase revealed by apoenzyme crystal structure. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J, Yang J, Kannan N, Madhusudan, Xuong NH, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS. Crystal structure of the E230Q mutant of cAMP-dependent protein kinase reveals an unexpected apoenzyme conformation and an extended N-terminal A helix. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2871–2879. doi: 10.1110/ps.051715205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlsson R, Zheng J, Xuong N, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Structure of the mammalian catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and an inhibitor peptide displays an open conformation. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1993;49:381–388. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993002306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng J, Knighton DR, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM, Ten Eyck LF. Crystal structures of the myristylated catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase reveal open and closed conformations. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madhusudan, Trafny EA, Xuong NH, Adams JA, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. cAMP-dependent protein kinase: crystallographic insights into substrate recognition and phosphotransfer. Protein Sci. 1994;3:176–187. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bossemeyer D, Engh RA, Kinzel V, Ponstingl H, Huber R. Phosphotransferase and substrate binding mechanism of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit from porcine heart as deduced from the 2.0 Å structure of the complex with Mn2+ adenylyl imidodiphosphate and inhibitor peptide PKI(5–24) EMBO J. 1993;12:849–859. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J, Ten Eyck LF, Xuong NH, Taylor SS. Crystal structure of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase mutant at 1.26 Å: new insights into the catalytic mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2004;336:473–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Wu J, Steichen JM, Kornev AP, Deal MS, Li S, et al. A conserved Glu–Arg salt bridge connects coevolved motifs that define the eukaryotic protein kinase fold. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:666–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sastri M, Barraclough DM, Carmichael PT, Taylor SS. A-kinase-interacting protein localizes protein kinase A in the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:349–354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408608102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tholey A, Pipkorn R, Bossemeyer D, Kinzel V, Reed J. Influence of myristylation, phosphorylation, and deamidation on the structural behavior of the N-terminus of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:225–231. doi: 10.1021/bi0021277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farazi TA, Waksman G, Gordon JI. The biology and enzymology of protein N-myristylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39501–39504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song KS, Sargiacomo M, Galbiati F, Parenti M, Lisanti MP. Targeting of a G alpha subunit (Gi1 alpha) and c-Src tyrosine kinase to caveolae membranes: clarifying the role of N-myristylation. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1997;43:293–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Dou J, Ding L, Spearman P. Myristylation is required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag–Gag multimerization in mammalian cells. J Virol. 2007;81:12899–12910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01280-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hantschel O, Nagar B, Guettler S, Kretzschmar J, Dorey K, Kuriyan J, Superti-Furga G. A myristyl/phosphotyrosine switch regulates c-Abl. Cell. 2003;112:845–857. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagar B, Hantschel O, Young MA, Scheffzek K, Veach D, Bornmann W, et al. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase. Cell. 2003;112:859–871. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patwardhan P, Resh MD. Myristylation and membrane binding regulate c-Src stability and kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4094–4107. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00246-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ames JB, Porumb T, Tanaka T, Ikura M, Stryer L. Amino-terminal myristoylation induces cooperative calcium binding to recoverin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4526–4533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka T, Ames JB, Harvey TS, Stryer L, Ikura M. Sequestration of the membrane-targeting myristyl group of recoverin in the calcium-free state. Nature. 1995;376:444–447. doi: 10.1038/376444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiergraber OH, Senin II, Philippov PP, Granzin J, Koch KW. Impact of N-terminal myristylation on the Ca2+-dependent conformational transition in recoverin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22972–22979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yonemoto W, McGlone ML, Taylor SS. N-myristylation of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase conveys structural stability. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2348–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaffarogullari EC, Masterson LR, Metcalfe EE, Traaseth NJ, Balatri E, Musa MM, et al. A myristoyl/phosphoserine switch controls cAMP-dependent protein kinase association to membranes. J Mol Biol. 2011;411:823–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gangal M, Clifford T, Deich J, Cheng X, Taylor SS, Johnson DA. Mobilization of the A-kinase N-myristate through an isoform-specific intermolecular switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12394–12399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu T, Matsuoka Y, Shirasawa T. Biological significance of isoaspartate and its repair system. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:1590–1596. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buetow L, Ghosh P. Structural elements required for deamidation of RhoA by cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12784–12791. doi: 10.1021/bi035123l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui J, Yao Q, Li S, Ding X, Lu Q, Mao H, et al. Glutamine deamidation and dysfunction of ubiquitin/NEDD8 induced by a bacterial effector family. Science. 2010;329:1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.1193844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jedrzejewski PT, Girod A, Tholey A, Konig N, Thullner S, Kinzel V, Bossemeyer D. A conserved deamidation site at Asn 2 in the catalytic subunit of mammalian cAMP-dependent protein kinase detected by capillary LC-MS and tandem mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 1998;7:457–469. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pepperkok R, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Konig N, Girod A, Bossemeyer D, Kinzel V. Intracellular distribution of mammalian protein ki-nase A catalytic subunit altered by conserved Asn2 deamidation. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:715–726. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yonemoto W, Garrod SM, Bell SM, Taylor SS. Identification of phosphorylation sites in the recombinant catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18626–18632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toner-Webb J, van Patten SM, Walsh DA, Taylor SS. Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25174–25180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masterson LR, Shi L, Metcalfe E, Gao J, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Dynamically committed, uncommitted, and quenched states encoded in protein kinase A revealed by NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6969–6974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102701108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams JA, McGlone ML, Gibson R, Taylor SS. Phosphorylation modulates catalytic function and regulation in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2447–2454. doi: 10.1021/bi00008a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Kennedy EJ, Wu J, Deal MS, Pennypacker J, Ghosh G, Taylor SS. Contribution of non-catalytic core residues to activity and regulation in protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6241–6248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805862200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson EE, Kornev AP, Kannan N, Kim C, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS. Comparative surface geometry of the protein kinase family. Protein Sci. 2009;18:2016–2026. doi: 10.1002/pro.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breitenlechner C, Engh RA, Huber R, Kinzel V, Bossemeyer D, Gassel M. The typically disordered N-terminus of PKA can fold as a helix and project the myristoylation site into solution. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7743–7749. doi: 10.1021/bi0362525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Derewenda ZS, Vekilov PG. Entropy and surface engineering in protein crystallization. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:116–124. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905035237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knighton DR, Bell SM, Zheng J, Ten Eyck LF, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. 2.0 Å refined crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase complexed with apeptide inhibitor and detergent. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1993;49:357–361. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stephen R, Bereta G, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Sousa MC. Stabilizing function for myristyl group revealed by the crystal structure of a neuronal calcium sensor, guanylatecyclase-activating protein 1. Structure. 2007;15:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fabbro D, Manley PW, Jahnke W, Liebetanz J, Szyttenholm A, Fendrich G, et al. Inhibitors of the Abl kinase directed at either the ATP- or myristate-binding site. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi Y, Seeliger MA, Panjarian SB, Kim H, Deng X, Sim T, et al. N-myristylated c-Abl tyrosine kinase localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum upon binding to an allosteric inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29005–29014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang J, Campobasso N, Biju MP, Fisher K, Pan XQ, Cottom J, et al. Discovery and characterization of a cell-permeable, small-molecule c-Abl kinase activator that binds to the myristyl binding site. Chem Biol. 2011;18:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kornev AP, Haste NM, Taylor SS, Eyck LF. Surface comparison of active and inactive protein kinases identifies a conserved activation mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17783–17788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607656103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steichen JM, Kuchinskas M, Keshwani MM, Yang J, Adams JA, Taylor SS. Structural basis for the regulation of protein kinase A by activation loop phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:14672–14680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.335091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams JA, Taylor SS. Divalent metal ions influence catalysis and active-site accessibility in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Protein Sci. 1993;2:2177–2186. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hereng TH, Backe PH, Kahmann J, Scheich C, Bjoras M, Skalhegg BS, Rosendal KR. Structure and function of the human sperm-specific isoform of protein kinase A (PKA) catalytic subunit Calpha2. J Struct Biol. 2012;178:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herberg FW, Bell SM, Taylor SS. Expression of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Escherichia coli: multiple isozymes reflect different phosphorylation states. Protein Eng. 1993;6:771–777. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.7.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duronio RJ, Jackson-Machelski E, Heuckeroth RO, Olins PO, Devine CS, Yonemoto W, et al. Protein N-myristylation in Escherichia coli: reconstitution of a eukaryotic protein modification in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1506–1510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hemmer W, McGlone M, Taylor SS. Recombinant strategies for rapid purification of catalytic subunits of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Anal Biochem. 1997;245:115–122. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.9952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collaborative Computational Project, No. 4 The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cook PF, Neville ME, Jr, Vrana KE, Hartl FT, Roskoski R., Jr Adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate dependent protein kinase: kinetic mechanism for the bovine skeletal muscle catalytic subunit. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5794–5799. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steichen JM, Iyer GH, Li S, Saldanha SA, Deal MS, Woods VL, Jr, Taylor SS. Global consequences of activation loop phosphorylation on protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3825–3832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.