Abstract

Transposase, TnpA, of the IS200/IS605 family member IS608, catalyses single-strand DNA transposition and is dimeric with hybrid catalytic sites composed of an HUH motif from one monomer and a catalytic Y127 present in an α-helix (αD) from the other (trans configuration). αD is attached to the main body by a flexible loop. Although the reactions leading to excision of a transposition intermediate are well characterized, little is known about the dynamic behaviour of the transpososome that drives this process. We provide evidence strongly supporting a strand transfer model involving rotation of both αD helices from the trans to the cis configuration (HUH and Y residues from the same monomer). Studies with TnpA heterodimers suggest that TnpA cleaves DNA in the trans configuration, and that the catalytic tyrosines linked to the 5′-phosphates exchange positions to allow rejoining of the cleaved strands (strand transfer) in the cis configuration. They further imply that, after excision of the transposon junction, TnpA should be reset to a trans configuration before the cleavage required for integration. Analysis also suggests that this mechanism is conserved among members of the IS200/IS605 family.

INTRODUCTION

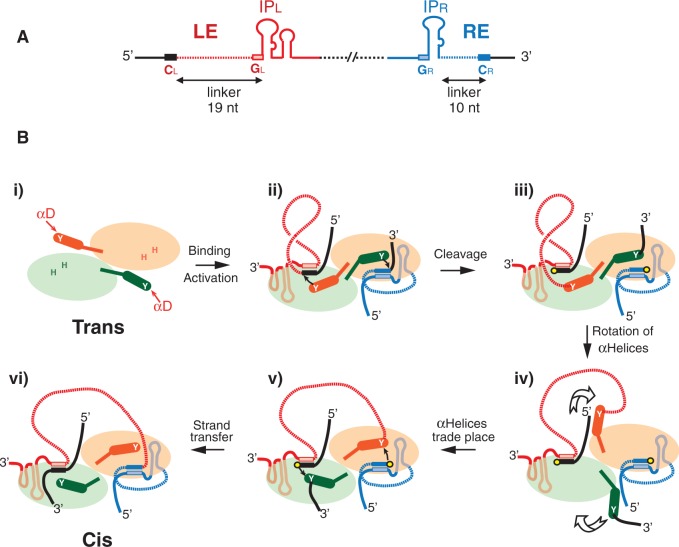

Members of the IS200/IS605 family of bacterial insertion sequences (IS) transpose using a unique mechanism involving single-strand DNA (ssDNA) intermediates (1,2). They generate a circular ssDNA intermediate by strand-specific excision, and this is then inserted 3′ to a specific tetra- or pentanucleotide sequence in an ssDNA target [e.g. into the lagging strand template at a replication fork; (3)]. Their transposases (TnpA) represent a subgroup of the HUH endonuclease family that use a single catalytic tyrosine (Y) as an attacking nucleophile. TnpA recognizes short sub-terminal imperfect palindrome structures at each end of the IS (Figure 1A) rather than the terminal inverted repeat sequences of classical ISs.

Figure 1.

IS608 and strand transfer model of transpososome. The left (LE) and right (RE) IS ends are shown in red and blue, respectively. The LE and RE linkers are indicated as dotted red, and blue lines and flanking DNA as black horizontal lines, respectively. (A) Organization of IS608 DNA ends. The left (red) and right (blue) sub-terminal secondary structures IPL and IPR are shown as the left and right cleavage (CL and CR) and guide (GL and GR) sequences. The distances in nucleotides between CL or CR and the foot of IPL or IPR (linker lengths) are indicated. (B) Cartoon of the IS608 transpososome and potential conformational changes. (i) The IS608 transposase TnpA dimer (pale green and pale orange) with hybrid active sites in a trans-form. These are composed of an HUH motif (H) from one TnpA monomer and a Tyrosine residue (Y) situated on αD-helix of the other (dark green and dark orange cylinders; shown by the arrow). (ii) The IS608 transpososome carrying an LE (red) and an RE (blue) bound to sites underneath each monomer. (iii) Covalent TnpA(Y127)–DNA complex after cleavage of the DNA ends in the presence of Mg2+. Corresponding 3′-OH residues are shown as yellow circles. (iv) Reciprocal rotation (indicated by large arrows) of the two αD-helices. (v) Formation of a cis active site configuration. (vi) Formation of the RE–LE transposon junction and donor joint from the DNA flanks.

Structural studies have shown that TnpA of IS608 (TnpAIS608) from Helicobacter pylori (4,5), ISDra2 (TnpAISDra2) from Deinococcus radiodurans (6) and TnpA from Sulfolobus solfataricus (7) are dimeric, with the catalytic Y located on an α-helix (αD) attached to the main body of the protein via a potentially flexible loop (Figure 1B). In the crystal structure, each catalytic site is a hybrid composed of the HUH (histidine–hydrophobic–histidine) motif from one monomer and the Y residue from the other [the catalytic site is said to be in a ‘trans’ configuration; Figure 1B i; (4)]. TnpA binds specifically to short sub-terminal secondary structures (IP) at the left (LE) and right (RE) IS ends (Figure 1B ii), and binding induces a conformational change (5) within each hybrid TnpA catalytic site that activates the protein for cleavages (Figure 1B iii).

The cleavage sites at LE and RE (CL and CR) are not recognized directly by TnpA. Instead, they form a complex set of interactions primarily with a tetranucleotide ‘guide’ sequence (GL and GR) 5′ to the foot of the hairpin (Figure 1A) and with additional nucleotides located to the 3′ of the hairpin (5,8). These interactions form a network of canonical and non-canonical base interactions that stabilize the nucleoprotein complex (8), the transpososome, within which the DNA strand cleavages and transfers are carried out.

Although these structures provided an informative picture of the overall nucleoprotein complex, our structural studies pertain only to Figure 1B i and ii. They did not allow visualization of authentic synaptic complexes carrying a single LE and RE copy at the same time. Neither did they provide information concerning the important step of strand transfer (the rejoining step where the phosphate is transferred from the catalytic tyrosine to its new 3′-OH partner) leading to excision of the ssDNA circular IS transposition intermediate or to the subsequent strand transfer involved in integration of this intermediate into its single-strand target.

A possible way of accomplishing such strand transfer during excision would be to assume a further major conformational change in which the two αD helixes rotate (Figure 1B iv) and trade places bringing the LE that is covalently attached to it via a 5′-phosphotyrosine linkage into position for attack by a 3′-OH of the cleaved RE to generate the transposon junction. Likewise, the similarly attached RE flank would be moved to the 3′-OH of the cleaved LE flank to generate the donor joint in a reciprocal strand transfer (Figure 1B v). In this configuration, the active sites are said to assume a ‘cis’ configuration. Similarly, the integration reaction requires cleavages of the transposon junction and of the target, rotation of the tyrosine–phosphate linked αD helixes and strand transfer (5).

This model for excision has several implications. It is important to note that there is a strong asymmetry in the organization of LE and RE (Figure 1A): CL is located 5′ to IPL at a distance (the linker) of 19 nt, whereas CR (located 3′ to IPR) is much closer to IPR, only 10 nt. As RE remains in place and the 5′-end of LE, attached to Y127 through the phosphotyrosine linkage, would be moved towards RE, the longer LE linker is required to reach the other active site in the proper orientation for strand transfer. This also raises the question of whether the TnpA catalytic sites remain in a cis configuration for the cleavage steps required for subsequent integration as suggested previously (5), or whether the enzyme is ‘reset’ and assumes the original trans conformation before initiating integration by cleaving the target and the transposon joint.

The results reported here address several questions central to understanding the different transposition steps of IS608. We provide evidence that supports a strand transfer model involving rotation of the two Y127-carrying αD helices. This is based on the in vivo and in vitro behaviour of LE derivatives of different linker lengths and of combinations of different TnpA mutants, as well as phenanthroline–copper DNA protection studies. The data further suggest that TnpA must be reset to assume a trans configuration before the subsequent cleavages and strand transfer involved in integration of the single-strand circle. This could provide a mechanism to prevent reversal of the transposition reactions and to ensure that transposition proceeds in a forward direction. We also provide bioinformatic evidence suggesting that this strand transfer mechanism is conserved among IS200/IS605 family members.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General procedures

Luria–Bertani broth was used for bacterial growth. E. coli strain JS219 [MC1061, recA1, lacIq; (9)] was used as a donor in mating-out experiments and in all other transposition-related assays. The recipient for mating-out experiments was MC240 [XA103, F−, ara, del (lac pro), gyrA (nalR), metB, argEam, rpoB, thi, supF]. Selective media included antibiotics as needed at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Ap), 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 25 μg/ml; kanamycin (Km), 25 μg/ml; nalidixic acid (Nx), 20 μg/ml; streptomycin (Sm), 300 μg/ml; and spectinomycin (Sp), 100 μg/ml. Standard techniques were used for DNA manipulation and cloning. Restriction and DNA modifying enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs or Fermentas. Plasmid DNA was extracted using miniprep kits (Qiagen). Polymerase chain reaction products were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). Restriction endonucleases, DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase were from Fermentas or New England Biolabs. Primer oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S2) were purchased from Sigma, whereas oligonucleotides used as substrates for in vitro experiments (Supplementary Table S1) were purchased from Eurogentec (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis purified). Where necessary, they were 5′- or 3′-end–labelled by 32P.

Constructions

The plasmid expressing TnpA–6His Y127F (TnpAY127F) has been described (4). The plasmid expressing the TnpA–6His G117A/G118A double mutant (TnpAG117A/G118A) was modified from plasmid pBS134 (2) by site-directed mutagenesis with primers G117/118Aup and G117/118Ado (Supplementary Table S2). The plasmids expressing two copies of tnpA to produce the heterodimers TnpAWT–TnpAY127F, TnpAH64A–TnpAY127F and TnpAWT–TnpAH64A/Y127F, were constructed as follows: tnpAY127F was amplified using primers Flag_Dir and Flag_Rev with a ribosome binding site on the 5′-end, a Flag tag on the 3′-end and an SphI site on both ends for cloning purposes. The SphI–SphI fragment was then inserted into SphI-linearized pBS134. The correctly orientated insertion was identified by sequencing, and the second mutation of H64A was then introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using primers H64A_Dir and H64A_Rev. Relevant mutations were introduced into LE or RE by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange Site-Directed mutagenesis kit, Stratagene) on pBS102 (1) using the corresponding primers (Supplementary Table S2). The required mutations were identified by sequencing.

In vivo assays

The transposition frequency was determined by mating-out assays using the conjugal plasmid pOX38Km as a target replicon (10) as previously described (11). Briefly, JS219/pOX38Km, containing a p15A derivative (pBS121) as a source of transposase under control of plac, was transformed with the different transposon donor plasmids. The wild-type IS donor plasmid was pBS102, a pBR322-based replicon carrying an ApR gene and a synthetic transposon composed of IS608 LE and RE flanking a CmR cassette (1). In vivo excision was monitored as previously described (1). For this, Escherichia coli strain MC1061recA was transformed with both the compatible plasmids pBS102 or its derivatives (ApR, CmR, carrying the transposon substrate) and pBS121 (SpRSmR specifying TnpA) and plated at 37°C with appropriate antibiotic selection. Plasmid DNA was extracted by the alkaline lysis method from overnight cultures of single transformant colonies grown at 37°C with 0.5 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and analysed on 0.8% Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) agarose gels.

Protein purification

Purification of ‘wild-type’ TnpA–6His, TnpAY127F–6His and the TnpAG117A/G118A–6His mutants from the E. coli Rosetta strain (Novagen) carrying corresponding expressing plasmids (pBS134 derivates) was as described previously (1,2). Heterodimer purification was carried out by sequential affinity chromatography. His-tag purification was used for the TnpA–6His homodimer, except for the last dialysis step. The dialysis buffer was 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10% Glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The His-tag purified protein was incubated with anti-flag M2-agarose (Sigma A2220) suspended in 9 volume of TNET buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA and 0.1% Triton X100) for 2 h at 4°C. The sample was centrifuged, washed four times with TNET buffer, resuspended in TNET buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml of FLAG peptide (Sigma, F3290) and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The anti-flag M2-agarose was removed by centrifugation, and the eluted protein contained in the supernatant was dialysed in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 20% Glycerol, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM DTT.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

32P radiolabelled (10 000 c.p.m. HIDEX liquid Scintillation Counter) together with unlabelled (>100-fold in excess, 0.6 µM) oligonucleotides were incubated with TnpA–6His in binding buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 15% glycerol, 3.5 mM DTT, 20 µg/ml of bovine serum albumin, 0.5 µg of poly-dIdC competitor and in the presence or absence of 5 mM MgCl2, as required, at 37°C for 45 min. Complexes were then separated in an 8% native polyacrylamide gel in TGE buffer (25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine and 1 mM EDTA) at 170 V for 3 h at 4°C.

Cleavage and strand transfer

The mixtures of complexes were treated by adding an equal volume of 0.6 mg/ml proteinase K in 0.4% sodium dodecyl sulphate and 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, at 37°C for 1 h (optional for 5′-end–labelled DNA but essential for 3′-end–labelled DNA) and were loaded in a 9% denaturing polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing 7 M urea and migrated in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid and 2 mM EDTA, pH 8) at 50 W for 1 h at room temperature.

Phenanthroline–copper footprinting

The phenanthroline–copper footprinting was carried out according to Sigman et al. (12). After the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), the whole gel was immersed in 200 ml of 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0). Twenty mililiters of 2 mM 1–10 phenanthroline/0.45 mM CuSO4 was added and incubated for 5 min. Twenty mililiters of 200× diluted mercaptopropionic acid was then added to start the reaction. The digestion lasted for 30 min at room temperature and was quenched by adding 20 ml of 30 mM neocuproine and left to stand for 5 min. The gel was then washed extensively with water and exposed to X-ray film for 2 h. Bands of interest were cut from the gel and eluted overnight at 37°C in elution buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulphate and 0.3 M NaCl. Eluted DNA was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in denaturing loading buffer (0.1% xylene cyanol and 0.1% bromophenol Blue in formamide) and separated on a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Immunoprecipitation

The immunoprecipitation was carried out by incubating the heterodimer TnpA–DNA complex formed in the presence of Mg2+ with anti-flag M2-agarose (Sigma A2220) suspended in 9 volume of TNET-B buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X100 and 40 µg/ml of bovine serum albumin) at 4°C for 2 h and washing in the same buffer five times. The DNA was released from the complex by adding denaturing loading buffer (0.1% xylene cyanol and 0.1% bromophenol Blue in formamide) and heating at 95°C for 5 min.

RESULTS

In vivo excision and transposition depends on the length of the LE and RE linkers

The asymmetry in the linker lengths of LE and RE is consistent with the cartoon model of IS608 transposition (Figure 1B). The strand transfer step requires that LE, attached via a phosphotyrosine residue to one of the two TnpA catalytic αD helices, and the RE flank, attached to the other, undergo rotation, whereas RE and the LE flank, both carrying a terminal 3′-OH, remain in place. To accomplish this, the LE linker should be sufficiently long. To investigate whether the observed asymmetry in the length of the LE and RE linkers indeed has functional significance, we analysed the effect of changing their lengths in vivo.

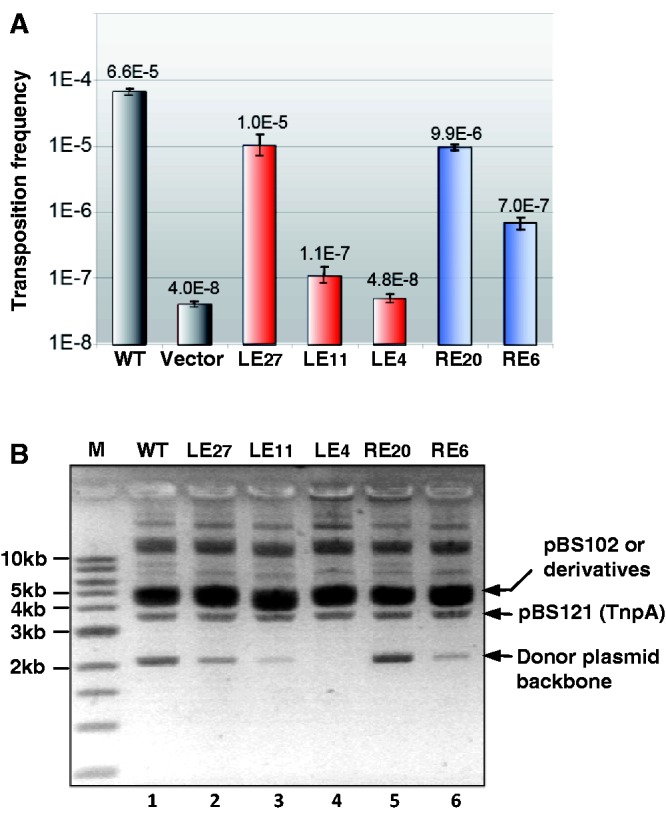

In the first step, we measured the activity of a synthetic IS608 transposon carried by plasmid pBS102 (1) (‘Materials and Methods’ section) and composed of LE, RE and a CmR gene cassette that replaces tnpA. Mutations were introduced into the wild-type LE with a 19-nt linker to increase (27 nt; LE27) or to decrease linker length (11 nt; LE11 and 4 nt; LE4). Transposase was supplied in trans from a compatible plasmid (‘Materials and Methods’ section). Overall transposition activity was measured using a standard mating-out assay (13) with the conjugative F-derived plasmid pOX38Km as a target.

Transposition (measured by CmR transfer; Figure 2A) of the LE27 mutant (1.0 × 10−5) was comparable with that of wild-type LE19 (6.6 × 10−5), whereas that of LE11 (1.1 × 10−7) was strongly reduced and approached background transfer levels. Transposition of LE4 (4.8 × 10−8) was undetectable compared with the background transfer frequency without transposase (4.0 × 10−8).

Figure 2.

LE and RE linker lengths and transposition efficiency. (A) Mating-out assay. For LE27, LE11 and LE4, the numbers indicate the distance between the cleavage site of LE and the 5′-foot of IPL. For RE20 and RE6, the numbers indicate the distance between the cleavage site of RE and the 3′-foot of IPR. For IS derivatives carrying a wild-type RE, columns are labelled according to the LE derivative used (LE27, LE11, LE4). Similarly, for IS derivatives carrying a wild-type LE, columns are labelled according to the RE derivative ends (RE20, RE6). Error bars show standard deviations from four matings with each derivative. (B) In vivo excision assay. Extracted plasmid DNA was separated by electrophoresis in a 0.8% TAE agarose gel. The relevant plasmid species are indicated. Lanes are labelled according to the LE derivative used with a wild-type RE (lanes 1–4) or according to the RE derivative together with a wild-type LE (lanes 5–6). Lane M is a linear 1-kb ladder standard marker.

Similar experiments were undertaken with RE. The results of mating-out assays using IS608 with a wild-type LE and mutant RE are presented in Figure 2A. Transposition of RE20, an RE derivative with an increased linker length (9.9 × 10−6), was only slightly less than that of wild-type RE10 (6.6 × 10−5), whereas that of RE6, in which the linker was reduced from 10 to 6 nt, was strongly reduced (7.0 × 10−7). Although we have not formally ruled out the possibility that the sequence of the linker itself may have some influence, these results support the idea that the length of the linker influences overall transposition frequency.

Overall transposition frequency is a product of the frequency of excision from the donor and that of insertion into the target. To determine whether excision was affected, plasmids containing transposons with different length spacers in left and right ends were exposed to transposase in vivo from a second compatible plasmid, and the level of excision was estimated by gel electrophoresis of plasmid DNA (1). This provides an estimate of excision activity by assessing the level of the donor backbone plasmid species lacking the transposable element. The results are shown in Figure 2B. The positions of the closed donor backbone, pBS121 providing TnpA, and the parental pBS102 derivatives are indicated. The pattern is similar to that obtained previously (1). Bands migrating high in the gel are presumably multimeric forms of the plasmid. Results for both LE and RE (Figure 2B) correlated well with those of the mating assay, indicating that reduction in the length of the LE linker compromises the excision step. IS608 with LE27 yielded slightly lower donor plasmid backbone levels than that with wild-type LE, whereas that with LE11 yielded lower product levels and that with LE4 failed to generate detectable levels.

Thus, although the linker length of both RE and LE is important for overall activity, the optimal length for LE is significantly larger than that for RE.

Reducing the LE linker length decreases the formation of excision complex in vitro

The sensitivity of LE activity to linker length may result from an effect on transpososome formation or on its activity once formed. To investigate whether the LE derivatives could form transpososomes, we used 5′-end–labelled LE derivatives and determined their ability to form complexes with an excess of wild-type RE (RE56) by EMSA as previously described (8). Note that neither the binding reactions nor the gels include Mg2+ which is required for cleavage. Therefore, these assays measure binding and synapsis. Two complexes were observed: a major band, CII, previously shown to include two IS ends and a TnpA dimer, and a minor faster migrating complex, CI, which we believe contains a single IS end (8). Wild-type LE generated a robust CII and some CI as expected (Figure 3A, lanes 2 and 3) as did LE27 (Figure 3A, lanes 5 and 6), whereas the capacity of LE11 to generate CII was reduced by 20% compared with LE19 (Figure 3A, lanes 8 and 9 and Supplementary Table S3). As LE11 binds robustly, as judged by its disappearance on increasing TnpA concentrations, this suggests that the CII complexes are less stable and may disintegrate during migration. Reducing the linker to only four nucleotides almost completely abolished CII formation (Figure 3A, lanes 11 and 12).

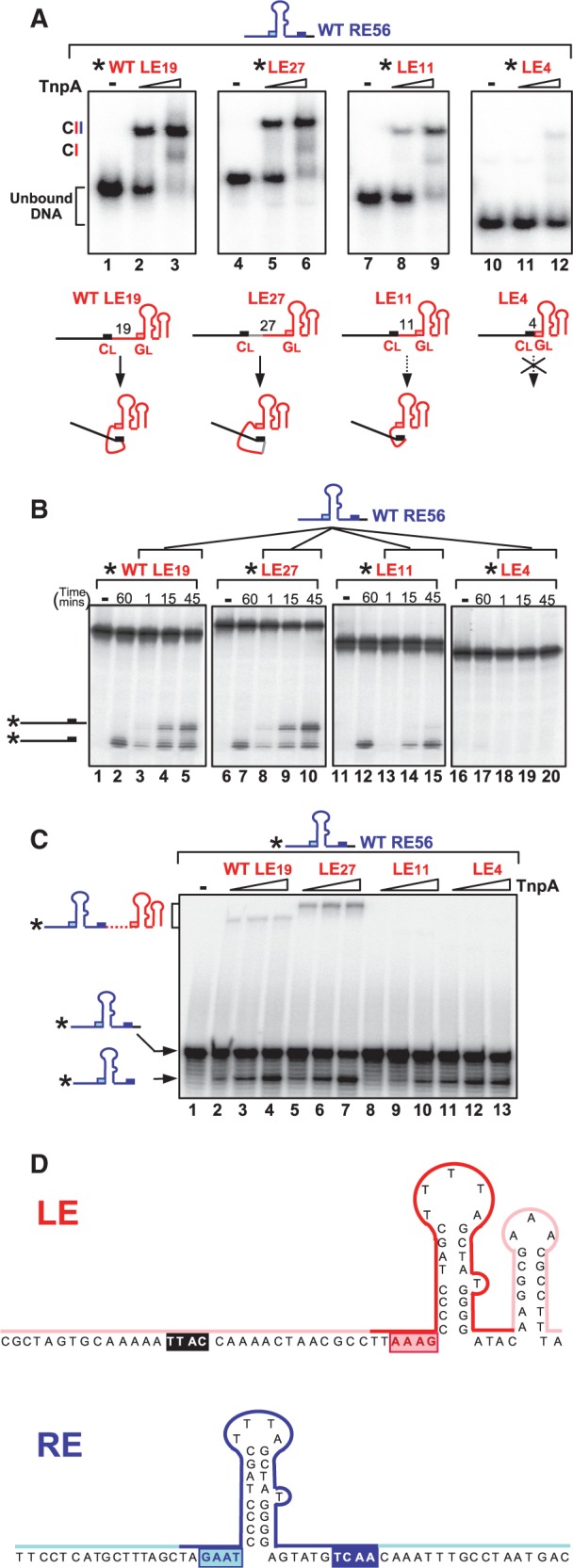

Figure 3.

In vitro activity of LE linker length variants. (A) EMSA analysis of complexes formed between TnpA, wild-type RE and LE variants. The 5′-end–labelled LE variants with excess unlabelled RE56 were incubated with TnpA without Mg2+; CII: the biologically relevant synaptic complex carrying labelled LE and non-labelled RE; RE56: length of the oligonucleotide used, including a wild-type RE linker; LE19, LE27, LE11 and LE4 indicate the LE linker length (see Supplementary Table S1); asterisk: the 5′-label; guide sequences GL (pink boxes); cleavage sequences CL (black boxes); hyphen: absence of TnpA–6His; triangle: increasing TnpA–6His concentrations (0.5 and 2.5 µM). Complexes were separated in 8% polyacrylamide native gels. Lower panel shows the potential folding capacity of LE variants because of the interaction between the cleavage site and guide sequence. (B) Cleavage of LE and donor joint formation. The 5′-end–labelled LE variants with excess unlabelled RE56 were incubated with TnpA in the presence of Mg2+. Samples were separated in a 9% sequencing gel. Hyphen indicates absence of TnpA–6His. The 60, 1, 15 and 45 indicate the reaction time (minutes) with 2.5 µM TnpA. Note that the 60 min point is without RE and is a measure of the cleavage activity without the accompanying strand transfer revealed by addition of RE. The 1, 15 and 45 min time points include RE and measure both cleavage and strand transfer. The products (the cleaved left flank and donor joint composed of the cleaved left and right flanks) are shown as cartoons on the left. (C) Cleavage of RE and transposon junction formation. The 5′-end–labelled RE56 with excess unlabelled LE variants were incubated with TnpA (0.1, 0.5 and 2.5 µM) in the presence of Mg2+. Samples were migrated on a 9% denatured sequencing gel for DNA analysis. The products (the cleaved RE and the RE–LE transposon junction) are shown as cartoons on the left. (D) Summary of phenanthroline–copper footprint of LE and RE within the IS608 transpososome. Red and dark blue indicate the zone protected by TnpA. Pink and pale blue indicate the exposed zone.

Correct interaction between the CL and the GL is essential to obtain a stable complex (5,8) and would be expected to require a minimum linker length. This is illustrated in the cartoon (Figure 3A). In this type of scheme, the CL/GL interaction could also occur when the linker length is increased from the 19-nt wild-type LE to 27 nt (LE27), but it might be reduced when the linker is shortened to 11 nt (LE11), and no interaction would be expected to occur if CL directly abuts GL as in LE4.

LE linker length affects cleavage and strand transfer efficiency in vitro

To monitor cleavage and strand transfer with the different LE derivatives, the samples including 5′-end–labelled LE derivatives described earlier in the text were incubated with Mg2+, and products were examined on a denaturing gel (Figure 3B). LE19 and LE27 were active both in cleavage (lanes 2 and 7) and strand transfer, generating a donor joint (lanes 3–5 and 8–10). LE11 also showed an equivalent cleavage to LE19 after 45 min (lane 12), although this occurred more slowly than with LE19 or LE27 (Supplementary Figure S1). However, the strand transfer activity was greatly reduced (lanes 13–15 and Supplementary Figure S1). LE4 seemed to be largely inactive in both cleavage (lane 17) and strand transfer (lanes 18–20), presumably reflecting its inability to form stable complexes (Figure 3A, lanes 11–12).

The 5′ LE labelling allows only donor joint formation to be monitored. This is postulated to require rotation of the αD helix carrying the 3′ flank, but not of that carrying LE, and is less likely to be affected by LE linker length, rotation of the loop carrying LE was, therefore, monitored by labelling the 5′-end of RE and identifying RE–LE transposon junctions. Both LE19 and LE27 clearly allowed cleavage and strand transfer of RE56 to generate the RE–LE junction (Figure 3C, lanes 2–4 and 5–7), consistent with the activity observed in donor joint formation (Figure 3B, lanes 3–5 and 8–10). RE cleavage was less apparent with LE11 than in conjunction with either LE19 or LE27, and no strand transfer could be detected (Figure 3C, lanes 8–10). The reduced RE cleavage activity in the presence of LE11 presumably results from a reduced ability of LE11 to form stable active complex. Cleavage of RE in the presence of LE4 was almost identical to that with wild-type LE19, but again, no strand transfer could be detected (lanes 11–13). LE4 bound TnpA poorly and could not form a stable complex with RE56 (Figure 3A, lanes 10–12). The cleavage observed could be because of preferential formation of TnpA complexes with two RE56 copies. This species was indeed detected in EMSA experiments (data not shown) and showed cleavage activity (Supplementary Figure S1).

Together, these results suggest that a longer linker in LE is necessary for correct stable interaction between CL and GL, and that this long 19-nt linker is also essential for strand transfer, supporting the transposition scheme shown in Figure 1B.

The LE linker is partially unprotected by the transpososome

The configuration of the transpososome carrying LE and RE, shown in Figure 1B ii, implies that the LE linker is exposed on the outside of the protein. To examine this, we used phenanthroline–copper footprinting. As Cu2+ activates TnpA (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3), we compared catalytically competent TnpA and Y127F catalytic mutant (1,4). EMSA experiments showed that this mutant can form CII with similar stability and mobility to that formed by wild-type TnpA (data not shown). A summary of the results obtained with the catalytically inactive TnpA is shown in Figure 3D and the corresponding gels in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3. Phenanthroline–copper treatment of the TnpA complex with 5′-end–labelled LE and unlabelled RE shows that IPL, and the 5′ (GL; AAAG) and 3′ (ATAC) sequences are protected, whereas a large region of the LE linker as well as the cleavage site (CL) are not protected. The pattern obtained with the TnpA complex and 5′-end–labelled RE and unlabelled LE was similar. The IPR, and the 5′ (GR; GAAT) and 3′ linker including the cleavage site (CR) are protected.

These results are consistent with the proposed scheme [Figure 1B and (5,8)] in which the LE linker is exposed on an exterior surface.

Reducing potential flexibility of TnpA αD decreases transposition activity in vivo and in vitro

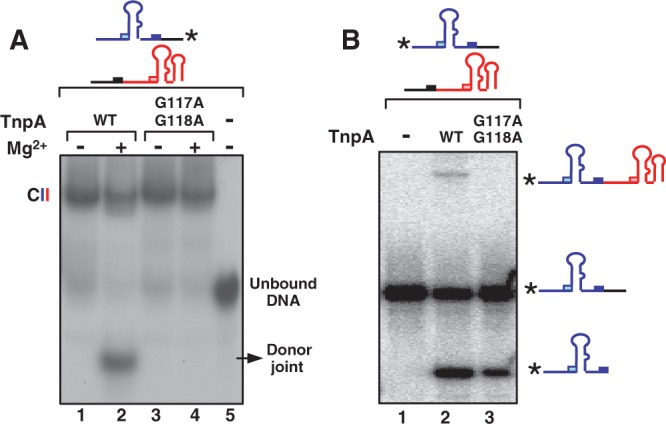

The strand transfer step in which LE and RE are joined during excision was proposed to occur by reciprocal rotation of the αD helices carrying the catalytic Y127 from their ‘trans’ position (Figure 1B). These helices are attached to the body of the protein by a flexible loop that includes a consecutive pair of glycine residues (G117 and G118) potentially providing the necessary flexibility. This idea was tested using a TnpAG117A/G118A double mutant.

Mating-out assays using TnpAG117A/G118A (6.60 × 10−7) show that transposition was greatly reduced compared with the wild-type TnpA (3.55 × 10−5).

Cleavage and strand transfer reactions of TnpAG117A/G118A were further studied in vitro. This mutant formed CII at similar levels to that of wild-type TnpA with a 3′-end–labelled RE70 and unlabelled LE80 in the absence of Mg2+ (Figure 4A, lanes 1 and 3). In the presence of the Mg2+, a fast migrating band was detected with wild-type TnpA (lane 2). This band was extracted from the gel and identified to be the donor joint (data not shown). This also implies that the donor joint is released from the transpososome after excision. However, no donor joint could be detected with TnpAG117A/G118A (lane 4). To discriminate whether this failure is because of either cleavage or strand transfer, and to examine whether the reciprocal event might occur generating the RE–LE junction, the reaction was carried out in the presence of Mg2+ using a 5′-end–labelled RE instead of the 3′-end–labelled RE and separated the products in a denaturing gel (Figure 4B). Clearly, TnpAG117A/G118A (lane 3) exhibited robust, but reduced, cleavage compared with wild-type (lane 2). Although initial cleavage occurred at a lower level, we were consistently unable to detect strand transfer products (in this case, the RE–LE transposon junction) in repeated assays. This would be expected if the movement of the αD helices was restrained; hence, they would not be able to rotate to assume the cis configuration.

Figure 4.

Activity of the TnpAG117A/G118A mutant. (A) EMSA analysis of complexes formed by TnpAG117A/G118A. The 3′-end–labelled RE with excess unlabelled LE was incubated with 2.5 µM wild-type TnpA (lanes 1 and 2) or TnpAG117A/G118A (lanes 3 and 4). Lane 5: TnpA free. Lanes 2 and 4: in the presence of Mg2+. (B) Cleavage of RE and transposon junction formation. The 5′-end–labelled RE with excess unlabelled LE incubated without (lane 1) or with 2.5 µM wild-type TnpA (lane 2) or TnpAG117A/G118A mutant (lane 3). Samples were electrophoresed in a 9% sequencing gel. The substrates (5′-end–labelled RE), its cleavage product and the RE–LE junction formed by strand transfer are indicated as cartoons.

A reset mechanism of TnpA from cis- to trans-forms during the transposition cycle?

Structural studies revealed that the TnpA catalytic site assumes a ‘trans’ configuration in which the HUH motif of one monomer and the nucleophilic Y127 from the other form an active site. This seems to be the configuration in which strand cleavage occurs. The data presented above are consistent with the idea that the second step, strand transfer, occurs after rotation of the αD helices, during which they exchange places leading to a ‘cis’ configuration of the active site (Figure 1B). The rotation model requires that TnpA forms the cis active site to perform the ligation step that terminates the strand transfer reaction. As the αD helices carrying Y127 are linked to the enzyme body by a flexible loop, we wished to know whether TnpA can assume a ‘cis’ form in which the catalytic site is constituted by the same monomer and, if so, whether such cis sites are catalytically active.

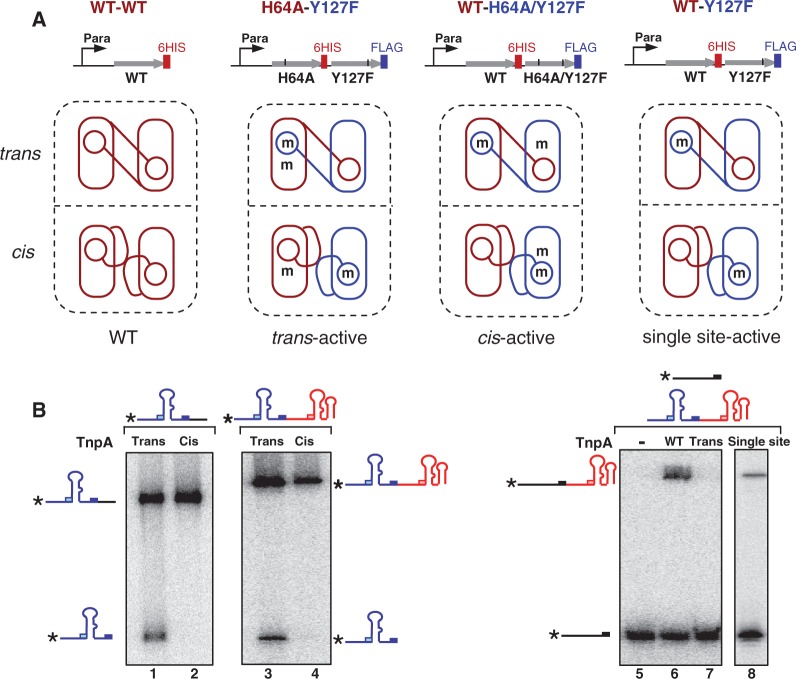

To determine whether TnpA can form catalytically competent active sites in both cis and trans configurations, we used heterodimeric TnpA derivatives carrying suitable inactivating mutations. Mutation of the catalytic site residues H64 or H66 (situated in the main body of the protein) or Y127 (present in the αD helix) inactivates TnpA (5). To obtain heterodimeric TnpA, we co-expressed two mutant genes from an artificially constructed operon. In the first case, this was composed of a tnpAH64A mutant with a C-terminal 6His-tag followed by a second mutant, tnpAY127F, with a C-terminal Flag-tag (DYKDDDDK). In the heterodimer, both catalytic sites should be inactive in the cis configuration, whereas one of the two should be active in the trans configuration [Figure 5A, second panel; see (5)]. We also constructed and expressed a second heterodimer carrying a wild-type TnpA monomer and a monomer of the double mutant, TnpAH64A/Y127F. In this heterodimer, both catalytic sites should be inactive in the trans configuration, whereas one of the two, the wild-type TnpA, should be active in the cis configuration (Figure 5A, third panel).

Figure 5.

Activity of trans-form and cis-form TnpA. (A) Construction of TnpA heterodimer. The top part of the figure shows the operon constructions. Grey arrow indicates the tnpA open reading frame. The short black vertical lines indicate mutations in tnpA. Para: arabinose promoter. In the lower part of the figure, protein expressed with a 6His-tag is shown in red, whereas that expressed with a Flag-tag is shown in blue. The rectangle represents the main body of TnpA, and the circle represents the αD-helix. Mutations of the His64 of HUH motif in the main body and Y127 in αD-helix are shown as ‘m’. The cis and trans configurations of the active site are indicated. (B) Cleavage and strand transfer activity of TnpA heterodimer. TnpA–Flag–TnpA–6His heterodimers were purified by consecutive anti-His and anti-Flag affinity chromatography. The reactions shown in lanes 1–4 used 5′-end–labelled RE70 and unlabelled RE70 (lanes 1–2) or 5′-end–labelled RE–LE junction and excess unlabelled junction (lanes 3–4) and were incubated for 45 min with Mg2+. The reactions were then immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag agarose before separating on a 9% sequencing gel. Cleavage activity in presence of trans TnpA heterodimer (lanes 1 and 3) or cis TnpA heterodimer (lanes 2 and 4). The reaction shown in lanes 5–7 used 5′-end–labelled pre-cleaved target with excess unlabelled junction incubated without (lane 5) or with WT TnpA (lane 6) or trans TnpA heterodimer (lane 7). Samples were separated on a 9% sequencing gel. Lane 8: activity of single–site-active heterodimeric TnpA by immunoprecipitation with anti-flag agarose. The 5′-end–labelled pre-cleaved target with excess unlabelled junction.

Heterodimers were obtained by two steps of affinity chromatography using consecutive Nickel agarose followed by anti-Flag agarose purification. In vitro cleavage was carried out by incubating 5′-end–labelled RE70 or the transposon junction with the TnpA heterodimer in the presence of Mg2+.

In this type of experiment, it is essential to eliminate the influence of monomer exchange after purification, as this could result in the formation of homodimers that could participate in the reaction. Although exchange of subunits in the trans-active TnpA heterodimer would not be expected to affect the results, as this would generate homodimers in which both sites are inactive (Figure 5A, second panel), this is not the case for the cis-active TnpA heterodimer (Figure 5A, third panel). In this case, exchange would generate both a wild-type and a double mutant homodimer. To eliminate these possibilities, the protein–DNA complex with the cis- and trans-active TnpA derivatives was isolated after the reaction by immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag agarose. The complexed DNA was then eluted and analysed in a 9% sequencing gel. Only the trans-active TnpA showed cleavage activity (Figure 5B, lanes 1 and 3), whereas the cis-active TnpA was totally inactive in cleavage of either RE (lane 2) or of the junction (lane 4).

To analyse the strand transfer of the TnpA heterodimer with the trans-active heterodimer, we used a 5′-end–labelled pre-cleaved target (with a free 3′-OH) and excess unlabelled junction. Although the trans-active heterodimer was able to cleave the RE–LE junction (Figure 5B, lane 3), it was unable to support strand transfer between the cleavage product and the pre-cleaved target (Figure 5B, lane 7).

We are unable to directly assay for strand transfer activity of the cis active site within the cis-active TnpA (Figure 5A, panel 3). This requires that the catalytic Y127 be linked to DNA generated by cleavage reaction, and we have shown that the cis active site is unable to support cleavage (Figure 5B, lanes 2 and 4). To circumvent this problem, we constructed and expressed a third type of heterodimer (single site-active; Figure 5A, fourth panel) carrying a wild-type tnpA with a C-terminal 6His-tag followed by the mutant tnpAY127F with a C-terminal Flag-tag. In this heterodimer, only a single catalytic site should be active in either the trans or the cis configuration. This heterodimer was also purified with two-step affinity chromatography. We used the same 5′-end–labelled pre-cleaved target with excess unlabelled RE–LE junction as for the trans-active TnpA. The reaction clearly generated a strand transfer product (Figure 5B, lane 8). As the TnpA with a trans-active site is proficient for cleavage (Figure 5B, lane 3) but not for strand transfer (Figure 5B, lane 7), this result suggests that strand transfer must have been accomplished by the cis active site.

In summary, these results, therefore, demonstrate that the trans-active TnpA site is proficient for cleavage but not for rejoining, whereas the cis-active TnpA site is proficient for rejoining but inactive in cleavage. Thus, a trans-active site is required for the next step of cleavage of the junction and target. This implies that following initial cleavage in the trans configuration and strand transfer after a transition to generate active sites in a cis configuration, TnpA must be reset to the trans configuration to continue the next step of transposition reaction, junction cleavage and IS integration.

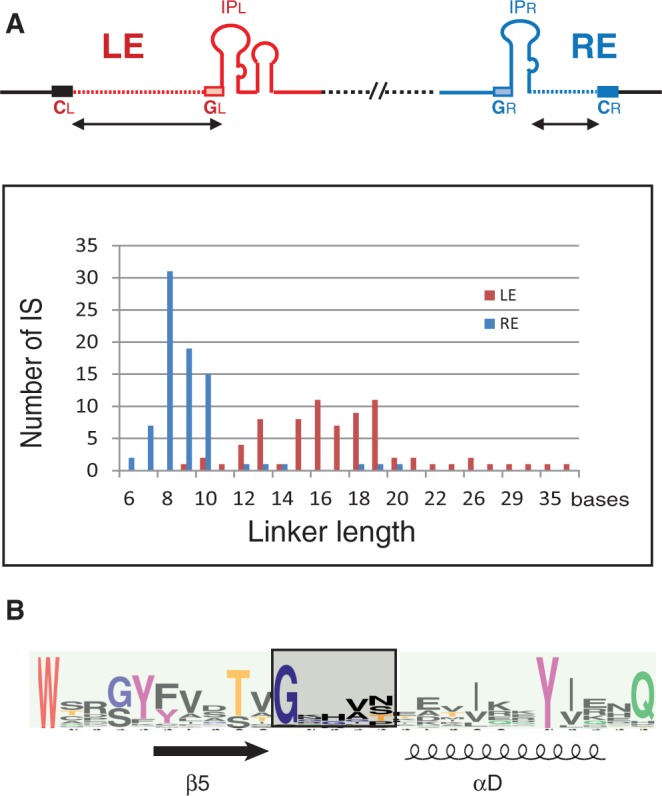

Implications for the IS200/IS605 family

IS200/IS605 family members are widespread. They are found in all major eubacterial and archaeal groups (ISfinder; Siguier in preparation) and share many key features. These include the unusual complementarity between the guide and cleavage sites, CL,R and GL,R, originally observed with both IS608 and ISDra2 (5,6), permitting recognition of the left- and right-end cleavage sites (2). The conservation also concerns the overall organization of the ends and their asymmetry—the left linker is always longer than the right (15–16 versus 8 nt) (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Key common characters of IS200/IS605 family members. (A) Organization of IS200/IS605 family members. The cartoon at the top recapitulates that presented in Figure 1A. Lower graph: linker length distribution of LE and RE from 76 and 80 different IS, respectively. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of TnpA potential flexible loop and surrounding regions of 89 members. WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/) was used to illustrate the consensus. The loop sequence is boxed, and secondary structures β5 and αD are shown. The catalytic Y (on the αD helix) and other conserved residues including the G (at the beginning of the loop sequence) are represented in such way that the overall height of stacks indicates the sequence conservation, whereas the height of symbols within the stack indicates the relative frequency of each amino acid at that position.

Furthermore, alignment using WebLogo (14,15) of the TnpA sequences from a large number of family members showed that at least one glycine residue is conserved at the beginning of the flexible loop (Figure 6B). Although in the case of ISDra2 where the equivalent positions are occupied by two different residues (S122 and E123), comparison of two available structures, nevertheless, suggests that the rotation of the αD helix is possible without violating the structural constraints imposed by the main-chain dihedral angles (Ramachandran plot) (6).

DISCUSSION

Although we know much about the mechanism of single-strand transposition, we have not captured the structure of transient intermediates necessary to understand the dynamic behaviour of the transpososome which is a key to the transposition process. Our present view of IS608 transposition implies considerable changes in transpososome conformation during the steps of transposition. These are thought to occur primarily by movement of two α-helices.

Organization of the ends

In vivo and in vitro results indicated that the IS608 linker length between the foot of the IP and the cleavage site is critical (Figure 1A). One reason for this is that formation of the catalytically competent transpososome, CII, involves a specific and complex set of interactions between CL and GL and between CR and GR (8). If the cleavage site and the guide sequence are too close to each other, CII does not assemble correctly as observed with the shorter LE substrate (Figure 3A).

On the other hand, if the LE linker undergoes rotation while attached to Y127 (Figure 1B), the strand transfer reaction, which generates the donor joint and the transposon junction during excision, should be more sensitive to linker length than the cleavage reaction. The results (Figure 3B and C and Supplementary Figure S1) indeed show that, in vitro, reduction in LE linker length had a more marked effect on strand transfer than on initial cleavage. Thus, the asymmetry in the organization of IS608 ends has functional significance.

αD helix is linked to the main body of TnpA by a flexible loop

Structural studies have shown that TnpAIS608 and another family member TnpAISDra2 from D. radiodurans are dimeric, each protomer carries a tyrosine nucleophile located on an α-helix (αD). This is in turn attached to the main body of the protein by a flexible loop. The αD-helix forms a catalytic site with an HUH motif located on the second monomer in the dimeric structure (trans configuration).

A principal feature of the strand transfer rotation model is the presence of this unconstrained loop. In TnpAIS608, this includes a consecutive pair of glycine residues (G117 and G118). Glycine can act as a pivot, as its main-chain dihedral angle is less restricted than that of all other amino acids. TnpAIS608 derivative TnpAG117A/G118A was severely affected in the ability to promote strand transfer (Figure 4), supporting the idea that reducing flexibility of the loop between αD and the body of the protein reduces the capacity of TnpAIS608 to undergo conformational changes.

TnpA catalytic sites: cis/trans configuration

We previously proposed that during the excision and integration steps in the transposition cycle, TnpAIS608 alternates between trans and cis configuration (5). Although currently there are no crystallographic data demonstrating that TnpAIS608, TnpAISDra2 or a related TnpA from Sulfolobus can assume a cis configuration (6,7), an inactive TnpA from D. radiodurans has indeed been crystallographically captured in this configuration (Protein Data Bank: 2fyx). Comparison of these structures also suggests that a cis/trans transition would be structurally reasonable. In this study, we, therefore, addressed the potential conformation changes using other approaches.

The rotation model raises the question of the catalytic properties of TnpA if it were to assume a cis configuration. αD helix rotation must form an alternative active site in which the 3′-OH carried by RE and by the LE flank can attack the 5′ phosphotyrosine bonds linked to LE and the RE flank, respectively, during excision (Figure 1B). Similarly, the 3′-OH carried by the cleaved left part of the target and by RE can attack the 5′ phosphotyrosine bonds linked to LE and to the right part of the target, respectively, during integration. Results using appropriately placed mutations in TnpA showed that a derivative which should generate a heterodimer with a single trans-active site was capable of robust cleavage of RE or of the RE–LE junction. It was unable, however, to catalyse detectable strand transfer using a pre-cleaved target and an RE–LE junction (Figure 5). On the other hand, a heterodimeric transposase in which only a cis conformation would be expected to be active is unable to catalyse the initial cleavages of RE or of the RE–LE junction. However, this derivative provides no information concerning strand transfer, as initial cleavage is required for formation of the phosphotyrosine intermediate, which then undergoes strand transfer. We, therefore, tested this using a third heterodimeric TnpA with a single active site in either a trans or cis conformation. This heterodimer allowed cleavage of the junction, presumably in the trans configuration to generate a covalently linked TnpA-LE intermediate allowing us to explore the rejoining activity of the cis configuration with a pre-cleaved target DNA. Results with this heterodimer demonstrated that the cis active site is active for rejoining. Thus, the cis active site is active for rejoining but inactive for cleavage. This, therefore, implies that the enzyme must be reset to the trans conformation for further cleavage activity.

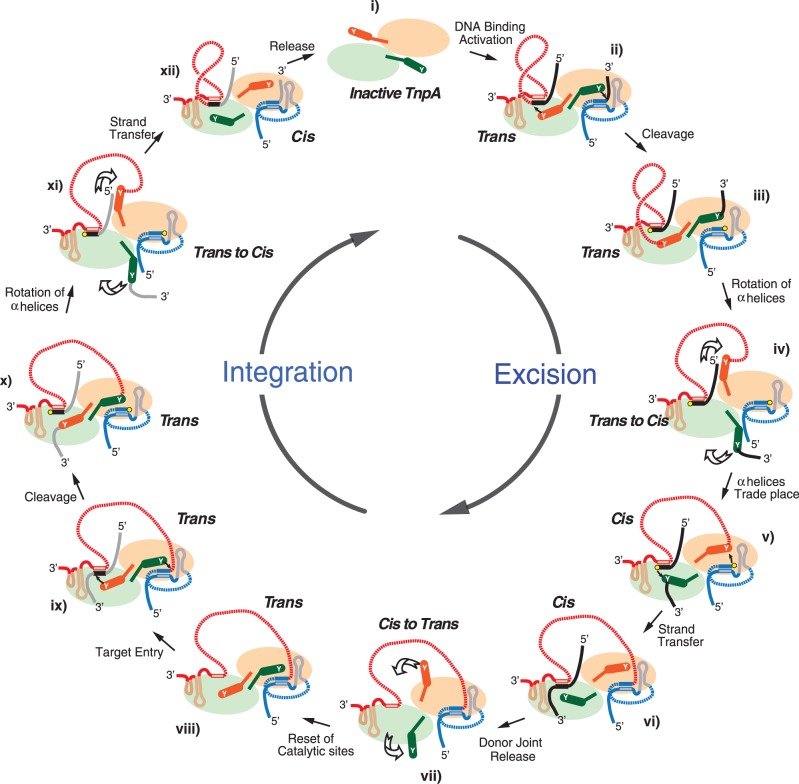

The reset model

These data have led to the following model for the dynamics in IS608 transpososome conformation during transposition (Figure 7): (i) in the absence of DNA, the TnpA dimer assumes an inactive form; (ii) LE and RE each bind and activate both trans configured catalytic sites; (iii) cleavage at both ends occurs within each of the trans active sites forming a 5′ phosphotyrosine linkage between Y127 and LE on one αD helix and between Y127 and the RE flank on the other; (iv) both αD helices then rotate reciprocally on the flexible loops; (v) the active sites assume a ‘cis’ configuration, bringing the attached RE flank into the correct position with respect to the 3′-OH of the LE flank and the attached LE to the 3′-OH of RE; (vi) strand transfer: the 3′-OH of the LE flank attacks the attached RE flank to generate the donor joint and reconstitute the joined donor backbone, whereas the 3′-OH of RE attacks the attached LE to generate the RE–LE transposon junction; (vii) the donor joint is released and both free αD helices again rotate reciprocally; (viii) TnpA is reset to the trans form ready for engagement of a suitable target site; (ix) target engagement occurs; (x) the RE–LE junction and target are cleaved using the trans form of TnpA, generating a phosphotyrosine linkage between Y127 and LE and between the right part of the target sequence; (xi) rotation of the two αD helices; and (xii) rejoining the cleaved junction and target in cis then generates the left and right transposon-donor joints completing integration. The alternative to this cleave–join–reset–cleave–join mechanism is that there is no reset, and the dimer remains in the cis configuration to cleave the RE–LE junction and target molecules. The evidence against this is the failure of the cis-active TnpA heterodimer to cleave the RE–LE junction.

Figure 7.

A strand transfer and reset model of IS608 transpososome. The same convention is used as in Figure 1B. (i) Inactive ground state of the dimeric TnpA with the active sites in the trans configuration. (ii) Binding of a copy of LE and RE resulting in TnpA activation. The excision complex is stabilized by base interactions between GL (pink rectangle) and CL (black rectangle) and between GR (pale blue rectangle) and CR (dark blue rectangle). (iii) Cleavage of RE and LE by Y127 resulted in the corresponding phosphotyrosine joined LE and RE flank. RE and LE flank, both with 3′-OH (yellow circles), remain bound to the protein presumably via interaction of CL with GL. (iv) Rotation of the two αD helices to assume the cis configuration with the accompanying movement of LE and the RE flank. (v) Attack of the LE phosphotyrosine bond by the RE 3′-OH and of the RE-flank phosphotyrosine bond by the LE-flank 3′-OH. (vi) Formation of the donor joint from the LE and RE flanks and of the RE–LE transposon junction. (vii) Reversal of the cis configuration to trans. (viii) Reset trans sites (here, it is assumed that the RE–LE junction remains bound to the TnpA dimer). (ix) Engagement of a new target (grey line) involving target sequence base interactions with GL and of GR with the RE–LE cleavage site. (x) Cleavage of the RE–LE junction by Y127 showing the corresponding phosphotyrosine joined LE and the future RE flank. (xi) Rotation of the two αD helices to assume the cis configuration with the accompanying movement of LE and the future RE flank. (xii) Formation of the LE and RE flanks to finalize the IS integration.

A reset mechanism such as this could provide an important regulatory mechanism. It would prevent reversal of the strand transfer reaction that generated the RE–LE junction (Figure 7 vi) during excision and would, therefore, ensure that transposition proceeds in a forward direction.

Analysis of an extensive library of IS200/IS605 family members showed that key features necessary for the rotation model, an extended LE linker compared with that of RE and a glycine residue, are conserved in various members of this widespread IS family.

Together, the results thus provide strong support for the rotation model, and the key conserved features of all family members suggest that this mechanism can be generalized to the entire IS200/IS605 family.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1–3 and Supplementary Figures 1–3.

FUNDING

Centre National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS, France); by ANR [ANR08 Blanc-0336 Mobigen to M.C]; intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (to F.D). Funding for open access charge: CNRS intramural funding.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank L. Lavatine, G. Duval-Valentin and O. Barabas for discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ton-Hoang B, Guynet C, Ronning DR, Cointin-Marty B, Dyda F, Chandler M. Transposition of ISHp608, member of an unusual family of bacterial insertion sequences. EMBO J. 2005;24:3325–3338. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guynet C, Hickman AB, Barabas O, Dyda F, Chandler M, Ton-Hoang B. In vitro reconstitution of a single-stranded transposition mechanism of IS608. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ton-Hoang B, Pasternak C, Siguier P, Guynet C, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Sommer S, Chandler M. Single-stranded DNA transposition is coupled to host replication. Cell. 2010;142:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronning DR, Guynet C, Ton-Hoang B, Perez ZN, Ghirlando R, Chandler M, Dyda F. Active site sharing and subterminal hairpin recognition in a new class of DNA transposases. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barabas O, Ronning DR, Guynet C, Hickman AB, Ton-Hoang B, Chandler M, Dyda F. Mechanism of IS200/IS605 family DNA transposases: activation and transposon-directed target site selection. Cell. 2008;132:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickman AB, James JA, Barabas O, Pasternak C, Ton-Hoang B, Chandler M, Sommer S, Dyda F. DNA recognition and the precleavage state during single-stranded DNA transposition in D. radiodurans. EMBO J. 2010;29:3840–3852. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HH, Yoon JY, Kim HS, Kang JY, Kim KH, Kim do J, Ha JY, Mikami B, Yoon HJ, Suh SW. Crystal structure of a metal ion-bound IS200 transposase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4261–4266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He S, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Johnson NP, Chandler M, Ton-Hoang B. Reconstitution of a functional IS608 single-strand transpososome: role of non-canonical base pairing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8503–8512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cam K, Bejar S, Gil D, Bouche JP. Identification and sequence of gene dicB: translation of the division inhibitor from an in-phase internal start. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6327–6338. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.6327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandler M, Galas DJ. Cointegrate formation mediated by Tn9. II. Activity of IS1 is modulated by external DNA sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;170:61–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guynet C, Achard A, Hoang BT, Barabas O, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Chandler M. Resetting the site: redirecting integration of an insertion sequence in a predictable way. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigman DS, Kuwabara MD, Chen C-HB, Bruice TW. Nuclease Activity of 1,10-Phenanthroline-Copper in Study of Protein-DNA Interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:414–433. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08022-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galas DJ, Chandler M. Structure and stability of Tn9-mediated cointegrates. Evidence for two pathways of transposition. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;154:245–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia J-M, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator 10.1101/gr.849004. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider TD, Stephens RM. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.