Abstract

To address how eukaryotic replication forks respond to fork stalling caused by strong non-covalent protein–DNA barriers, we engineered the controllable Fob-block system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This system allows us to strongly induce and control replication fork barriers (RFB) at their natural location within the rDNA. We discover a pivotal role for the MRX (Mre11, Rad50, Xrs2) complex for fork integrity at RFBs, which differs from its acknowledged function in double-strand break processing. Consequently, in the absence of the MRX complex, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) accumulates at the rDNA. Based on this, we propose a model where the MRX complex specifically protects stalled forks at protein–DNA barriers, and its absence leads to processing resulting in ssDNA. To our surprise, this ssDNA does not trigger a checkpoint response. Intriguingly, however, placing RFBs ectopically on chromosome VI provokes a strong Rad53 checkpoint activation in the absence of Mre11. We demonstrate that proper checkpoint signalling within the rDNA is restored on deletion of SIR2. This suggests the surprising and novel concept that chromatin is an important player in checkpoint signalling.

INTRODUCTION

The path of a replication fork is loaded with obstacles, which impose a frequent threat for the replication fork and make the process of DNA replication fragile. These obstacles are mainly caused by exogenous agents or reactive metabolic products that inevitably damage the DNA. In addition, particular regions in the genome, such as replication slow zones, constitute a challenge to replication fork movement and are associated with a high incidence of chromosomal rearrangements (1,2). Natural replication-impeding sequences also exist, which may form tight protein–DNA complexes that potentially inhibit fork progression (3,4). Replication fork arrest is often temporary, and if the fork is stabilized during this event, DNA synthesis can resume after the obstacle is removed. However, if cells are unable to resume replication, the arrest becomes irreversible, and fork collapse may occur. Recombination may then be a necessary outcome for the cell. Appropriate cellular responses to stalled replication forks are thus essential both for efficient DNA synthesis and the maintenance of genomic stability.

The cellular responses to fork stalling in eukaryotes have been most intensively studied using genotoxic drugs, but recently, more focus has been dedicated to study the cellular response to natural existing replication fork barriers (RFB). Of these, the best studied are the RFB found in the rDNA locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which on binding of the Fob1 protein constitutes a strong protein–DNA barrier (5,6), and the replication termination sequence 1 (RTS1) barrier in S. pombe, which generates unidirectional replication at the mating-type locus (7).

The cellular response to replication fork stalling caused by naturally existing RFBs may differ in many aspects from the response to genotoxic drugs such as hydroxurea (HU). In the latter case, it is important to maintain a coupling between DNA helicase activity and polymerase activity to avoid extensive DNA unwinding and thereby generation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) exposure ahead of the stall site (8). Physical barriers, which hinder helicase movement, will not have to cope with this problem, but replisome stabilization is still essential during stalling. This could require a functional checkpoint as seen for replisome resumption after methyl methane sulphonate (MMS) or HU exposure (9–13). However, experiments with ectopically placed RFBs in S. cerevisiae disclose a checkpoint independent pausing and recovery of the replisome at these barriers, contrasting the regulation of HU-stalled forks (14). A similar study from S. pombe reveals that cell viability in the presence of inducible RTS1 barriers does not require checkpoint kinases, but opposed to the former study, stalling rapidly leads to replisome disassembly (15).

Recombination is often associated with stalled replication forks. Although unscheduled recombination is undesirable, there is accumulating evidence that homologous recombination (HR) does play crucial roles in the rescue of stalled replication forks both in E. coli and in eukaryotic cells (15–18). Recently, rescue of a disassembled fork at the RTS1 barrier in S. pombe was suggested to occur via a double-strand break (DSB) independent but recombination dependent pathway through template switching, which leads to chromosomal rearrangements (19,20). In contrast, replication fork stalling at an ectopically placed RFB in S. cerevisiae has been suggested to be stably maintained in a recombination independent way (14). These discrepancies may reflect different evolutionary choices between organisms and thus highlight the importance of further investigations to dissect the cellular response to roadblocks and to better understand the relation between stalled forks, checkpoint and recombination events.

The rDNA constitutes a perfect in vivo model system for analysing replication fork stalling, as this is a natural event, taking place during each cell cycle in this compartment. Furthermore, the unidirectional mode of DNA replication and the repetitive nature of the rDNA add a strong pressure on the active replication fork, and thus, identification of factors involved in replication fork integrity may prove easier using the rDNA as a model system. To analyse the cellular response to replication fork stalling, we therefore took advantage of the rDNA and engineered a cellular system in S. cerevisiae, which allows us to strongly induce and control the barriers at this location. Using this Fob-block system, we uncover a pivotal role for the MRX complex at RFBs, which differs from its acknowledged role in DSB processing. Moreover, our studies reveal the unprecedented concept that chromatin context influences checkpoint activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids

Strains used were constructed using standard genetic techniques and are listed in Supplementary Table S1. All strains are derivatives of the original W303 genetic background with a mutation in RAD5. We therefore confirmed that the growth defect observed for mre11Δ on galactose was not due to a non-functional RAD5 (data not shown). All deletions of MRE11, XRS2 and RAD50 were tested for MMS sensitivity, as these strains very easily obtained suppressors, which gave rise to MMS resistance (data not shown).

To generate yeast strains with RFBs inserted ectopically at chromosome VI, we modified pFA6a-based plasmids in the following way. The RFB sequence was generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on genomic DNA using primers LBo-81 and LBo-82, respectively. The PCR product obtained was cloned into pFA6a-KanMX4 using AvrII and SpeI cloning sites, ligation was done in the presence of the enzyme and positive colonies were verified by sequencing (KanMX6-3xRFB, pLB112). To obtain strains with eRBF, the PCR product obtained with primer LBo-50 and LBo-117 on pLB112 was used for homologous recombination-mediated integration of 3xRFB close to ARS607 in a non-transcibed region between ATG18 and ROG3. Plasmid pML38 for integrating the tetO array into the intergenic region iYFR020W is described in (21). Plasmids and primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2 and S3, respectively.

Yeast growth

Cells were grown at 30°C in YP medium supplemented with 2% raffinose (YPRaff), if not otherwise stated. Overnight cultures were diluted and grown for two generations before cells were synchronized in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by the alpha-factor mating-type pheromone (Lipal Biochem, Switzerland) in YPRaff (pH 3.5) for 90 min. Induction of the FOB1 gene was carried out in G1-arrested cells for 90 min in YPRaff supplemented with 3% galactose (pH. 3.5) before cells were washed several times and released into S phase in YPRaff supplemented with 3% galactose.

Protein expression

Yeast strain LBy-365 was grown overnight in YPRaff medium at 30°C. Culture was diluted and grown to a log phase culture of 1 × 107 cells/ml, before it was divided into two cultures. Two percent galactose was added to one of the cultures. Aliquots were taken from each culture at the indicated times. Trichloroacetic acid precipitation of proteins were performed, sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% gels) conducted and western blotting carried out using monoclonal antibody against GST (Santa Cruz) and Mcm2 (Santa Cruz).

Spot assays

Cells were grown in liquid YPRaff O/N, adjusted to OD600 = 1 and 10-fold serial dilutions spotted on YPD and YP + 3% galactose plates, respectively. Plates were incubated for 2 days at 30°C.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Samples were taken for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis during the various experiments and processed as described in (22). Samples were analysed in a BD FACSCalibur.

2D DNA gels

Cells were grown at 20°C. Yeast genomic DNA was isolated from 2 × 109 cells by using Genomic-tip 20/G (QIAGEN) as described in (23). After the digestion with restriction enzymes (BglII for the rDNA), the DNA was subjected to neutral/neutral 2D gel analysis as described in (24). Southern blotting was carried out using probes with primers indicated in Supplementary Table S3 and shown in Figure 1A. Image analysis was performed using the Quantity One software. Replication fork stalling was quantified by calculating the percentage of the specific replication fork stalling signal relative to the 1 N spot followed by normalization to the values to time point 0.

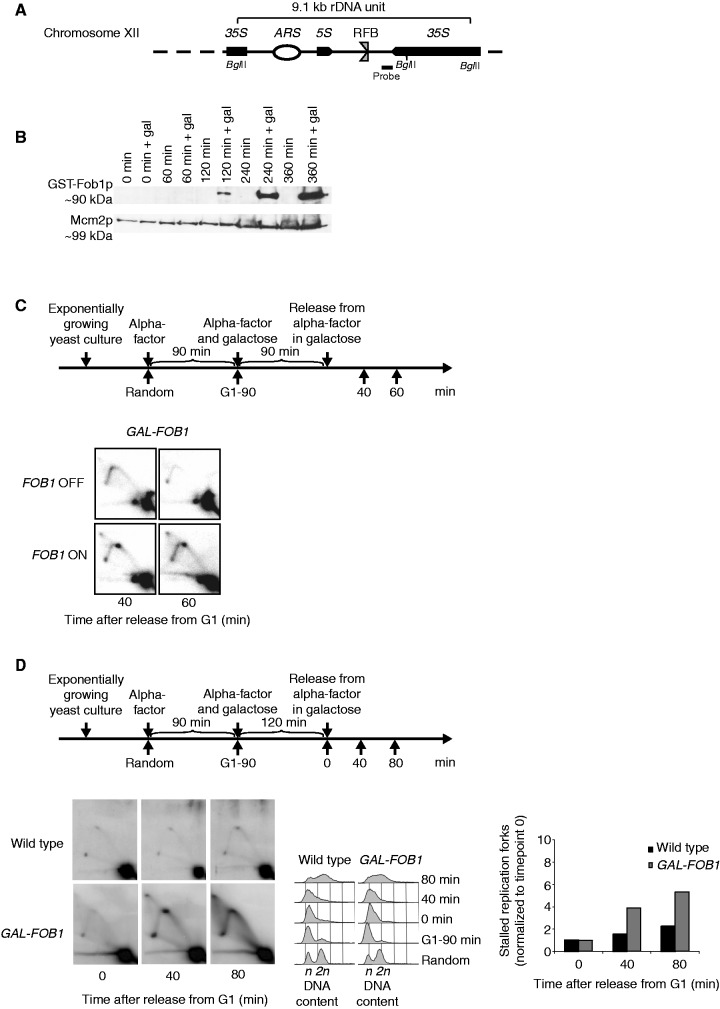

Figure 1.

Verification of the Fob-block system. (A) Schematic illustration of a single 9.1 kb repeat of the rDNA in S. cerevisiae found on Chr. XII. Position of the RFB, origin of DNA replication (ARS), 35S rRNA (35S) and 5S rRNA (5S) genes are indicated. Position of probe used for Southern blotting and BglII cleavage sites used for the 2D DNA gel are also shown. The RFB allows progression of the replication fork in the same direction as 35S rRNA transcription, but not in the opposite direction when Fob1p is bound to the sequence (B) Fob1p expression after different times of galactose induction (0, 60, 120, 240 and 360 min) together with negative controls (non-inducing conditions) on strain LBy-365. (C, upper panel) Outline of yeast culture treatment preceding isolation of DNA for 2D DNA gel analyses. (C, lower panel) 2D DNA gel analysis (strain LBy-413) reveals replication fork stalling in the rDNA (Chr. XII) during inducing conditions (FOB1 ON), but not during non-inducing conditions (FOB1 OFF); see text for details. (D) 2D DNA gel analyses conducted to compare replication fork stalling efficiency at the RFB between a wild-type (LBy-1) strain with endogenous levels of Fob1 and a strain (LBy-413) with overexpression of Fob1. During the experiment, the wild-type strain was kept in glucose medium to give optimal conditions for this strain, whereas LBy-413 was treated as indicated above the 2D gel. Both strains were synchronized. On the right is shown a quantification of replication fork stalling (see ‘Material and Methods’ section for further explanation), and in the middel is shown FACS profiles for the strains. The n and 2 n is DNA content in G1 and G2, respectively.

DSB assay

Isolation of intact yeast DNA was basically performed as described previously with few modifications (25). Briefly, 9 × 107 cells/plug were used. Cells were re-suspended in 50 µl of cold buffer [0.1 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 8, 0.01 M Tris, pH 7.6, and 0.02 M NaCl] containing 5 µl of zymolase (zymolase-20T Arthrobacter luteus, 20 000 U/gm) at a stock concentration of 20 mg/ml. The suspension was warmed for 42°C for 10 s and mixed briefly with 50 µl of 1% low melting agarose. Digestion was carried out with BglII (60 units). Gel plugs were loaded into wells of a 1% agarose gel, which was run in TBE at 2 V/cm at 4°C for 20 h. Standard Southern blotting was carried out.

Pulsed field gel electrophoresis

All steps for pulsed field gel electrophoresis were performed as described in (25). Southern blotting was carried out using a probe for Chr. XII, and for Chr. II, primers for these probes are indicated in Supplementary Table S3. Quantification of the amount of Chr. XII and Chr. II entering the gel was performed using Quantity One software, and shown is an average of two experiments performed. The intensity of the signals at the different time points is calculated relative to timepoint 0, which is set to 1.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

In all, 50 ml of cells (2 × 107 cells/ml) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at 25°C. Glycine was added to a final concentration of 125 mM, and the incubation continued for 5 min. Cells were harvested and washed with 1 ml PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 8 mM Na2HPO42·H2O, pH 7). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using polyclonal antibody against RPA (RFA1) (Agrisera, AS07 214). Antibody was bound to Dynabeads M-280 (Invitrogen Dynal AS, Norway) (5 µl/sample). Dynabeads without antibody were used as background control. The cell samples were added to 700 µl of lysisbuffer (140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% triton-x-100, 50 mM hepes, pH 7.5, protease inhibitors: 0.2 mM PMSF, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.5 µg/ml of leupeptin, 20 µM antipain, 1 µg/ml of pepstatin A, 100 µg/ml of TLCK, 100 µg/ml of TPCK) and acid-washed glass beads before they were lysed using a ribolyser (Hybaid Ltd.). The samples were enriched for chromatin-bound protein by centrifugation at 13 000 r.p.m. in 15 min. In all, 1 ml of lysis buffer was added to the DNA with the bound proteins before the DNA was sonicated to give fragments of ∼500–1000 bp. The extract was split into two tubes either containing antibody coupled Dynabeads or Dynabeads alone (control) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. Afterwards, the beads were washed twice with lysis buffer, once with wash buffer (500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 10 mM Tris, pH 8, protease inhibitors as in the lysis buffer) and once with TE buffer. The interactions between antibodies and beads were reversed by addition of TE + 1% SDS and incubation at 65°C for 10 min. Samples were incubated at 65°C overnight in TE + 1% SDS. Next day, the samples were proteinase K digested for 2 h at 37°C before LiCl was added and phenol-chloroform extraction performed. The recovered DNA was amplified with real-time PCR using a Stratagene MX3000 and performed with 5× AHPolHS EvaGreen qPCR Mix Plus (AH zymes). ChIP data were averaged for three independent experiments with real-time PCR performed in duplicate. Error bars are standard deviations. Fold increase is calculated as the amount of protein bound to Dynabeads (Ip) with antibody compared with the amount of protein bound to Dynabeads alone (Beads): Fold increase = 2 (CT Input – CT Ip)/2 (CT Input – CT Beads). The height of the bars in the figure represents fold increase relative to time point 0. Sequences of primers used can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

Rad53 in situ kinase assay

All steps of the in situ kinase assay (ISA) are as described in (26), except that 5 µCi/ml of [γ-32P] adenosine triphosphate was used. For every sample, protein concentration was determined by Comassie blue before equal loading on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels along with 5 µl of a standard (MMS ctrl) containing a known amount of MMS activated Rad53p. Dried filters were exposed to a Typhorn Trio+. After exposure, filters were re-probed with goat anti-Mcm2 (Santa Cruz) to check loading and to allow comparison among different gels and mutants. Experiments were performed 2–3 times with similar results.

RESULTS

Generation of a controllable Fob-block system with inducible RFBs in the rDNA

To address how eukaryotic replication forks respond to fork stalling caused by strong non-covalent protein–DNA barriers, we engineered a controllable Fob-block system in S. cerevisiae, which take advantage of the rDNA as a model system. We generated a yeast strain with expression of the FOB1 gene under control of the GAL1,10 promoter. Induction of FOB1 generates high levels of active RFBs in the rDNA and causes unidirectional replication at this locus owing to stalling of leftward moving forks (Figure 1A). This strain is referred to as GAL-FOB1. The GAL1,10 inducible promoter enables us to obtain a rapid induction of FOB1, when cells are grown in the presence of galactose (Figure 1B). To further verify that the Fob-block system has active RFBs on FOB1 induction, we performed classical neutral/neutral 2D gel analyses for the rDNA locus. We analysed a DNA fragment that would run as a simple Y-structure. If replication fork arrest occurs at the RFBs, partially replicated molecules will accumulate and give a distinctive dot on the Y-arc. Cells were grown as outlined in Figure 1C (top). As control, a yeast culture was also grown under repressed conditions. A dot is seen on the Y-arc at 40 and 60 min after release from the G1 block under inducing conditions (Figure 1C, bottom), but not during repressed conditions. Furthermore, a comparison of the GAL-FOB1 and a wild-type strain, where FOB1 is expressed from its endogenous promoter, reveals a significant higher level of fork stalling at the RFB site in GAL-FOB1 cells relative to wild-type cells, as visualized by the appearance of the distinctive dot in 2D gels (Figure 1D).

In conclusion, the Fob-block system allows induction of active protein–DNA barriers in the rDNA, which lead to replication fork stalling.

Growth of Fob-block cells requires the MRX complex, but not homologous recombination

Wild-type Fob-block cells were next tested by comparing growth of cells on glucose (FOB1 OFF) with growth on galactose (FOB1 ON). The GAL-FOB1 strain does not show any significant growth defect on galactose compared with a wild-type strain, demonstrating that cells with the Fob-block system are able to efficiently overcome induced RFBs without significantly affecting cell growth (Figure 2A).

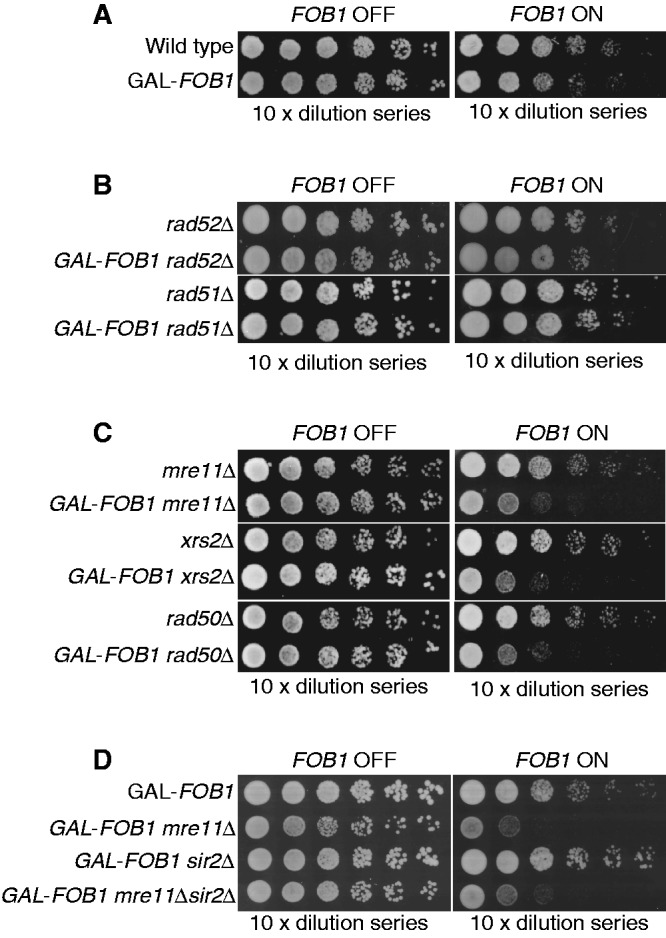

Figure 2.

Fob-block cells require the MRX complex, but not homologous recombination for proper cell growth. Also, 10-fold serial dilutions of raffinose-grown cultures (non-induced) were spotted on glucose and galactose plates. (A) Shown are isogenic strains of wild-type (LBy-1), GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413) (B) Shown are isogenic strains of rad52Δ (LBy-108), GAL-FOB1 rad52Δ (LBy-588), rad51Δ (LBy-14), GAL-FOB1 rad51Δ (LBy-612) (C) Shown are isogenic strains of mre11Δ (LBy-605), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756), xrs2Δ (LBy-80), GAL-FOB1 xrs2Δ (LBy-774), rad50Δ (LBy-615), GAL-FOB1 rad50Δ (LBy-581). (D) sir2Δ does not suppress the mre11Δ growth defect. Shown are isogenic strains of GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756), GAL-FOB1 sir2Δ (LBy-888), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ sir2Δ (LBy-909).

In S. cerevisiae, forks arrested at RFBs in the rDNA may be prone to collapse and thereby recombine (27). Indeed, replication- and FOB1-dependent DNA breaks have been mapped to the RFB regions (28). On the contrary, when RFBs are taken out of the rDNA context, fork arrest does not give rise to observable recombination, and survival does not depend on Rad52 (14). To investigate whether our Fob-block system requires HR for cell survival, the GAL-FOB1 strain was combined with deletions of central components of the RAD52 epistasis group, and cell growth was tested. Deletion of either RAD52 or RAD51 in the GAL-FOB1 strain did not give rise to any growth defects on galactose plates relative to a RAD52 or RAD51 deletion mutant without the Fob-block system (Figure 2B). This reveals that recovery from the induced RFBs is independent of HR.

Surprisingly, when the different components of the MRX complex were deleted (MRE11, RAD50 or XRS2) in the GAL-FOB1 strain, a strong growth defect was observed on galactose plates for all strains relative to the MRE11, RAD50 or XRS2 deletion mutants alone (Figure 2C). This highlights a need for MRX to cope with active RFBs, although HR per se is not required. Interestingly, even though active RFBs are a normal feature of rDNA, overexpression of Fob1 adds a pressure on the cell, which allows for identification of proteins required for cells to cope with RFBs or for normal fork integrity of the unblocked forks.

Binding of the Fob1 protein to RFB not only promotes polar replication fork arrest but also loads the NAD-dependent histone deacetylase Sir2 at the RFB via a protein complex called regulator of nucleolar silencing and telophase exit (29,30). Loading of Sir2 is known to cause rDNA silencing, which suppresses intrachromatid recombination. To establish whether requirement for the MRX complex on overexpression of Fob1 is due to replication fork stalling or Sir2 mediated at the rDNA, we performed growth analysis of a GAL-FOB1 sir2Δ deletion strain and a GAL-FOB1 mre11Δsir2Δ strain. Absence of SIR2 does not give rise to any growth defect in our GAL-FOB1 strain, and the growth defect scored in the absence of MRE11 is not suppressed by a SIR2 deletion (Figure 2D). This supports the idea that the MRX complex is required at the rDNA owing to replication fork stalling and not owing to an affected rDNA silencing on overexpression of Fob1.

In conclusion, our genetic data unravel a recombination independent function of MRX for cell growth on increased replication fork stalling in the rDNA locus.

Absence of the MRX complex leads to more ssDNA at protein–DNA barriers

As the Fob-block system is insensitive to the lack of Rad51 and Rad52, overexpression of Fob1 neither seems to induce more DSBs per se, which require HR for repair, nor to generate a need for HR-dependent fork restart at RFBs. It is thus unlikely that the need for MRX at active RFBs derives from its well-established role in early resection upstream of HR (31–33) or its scaffold role for recruiting the more extensive resection machinery (34,35).

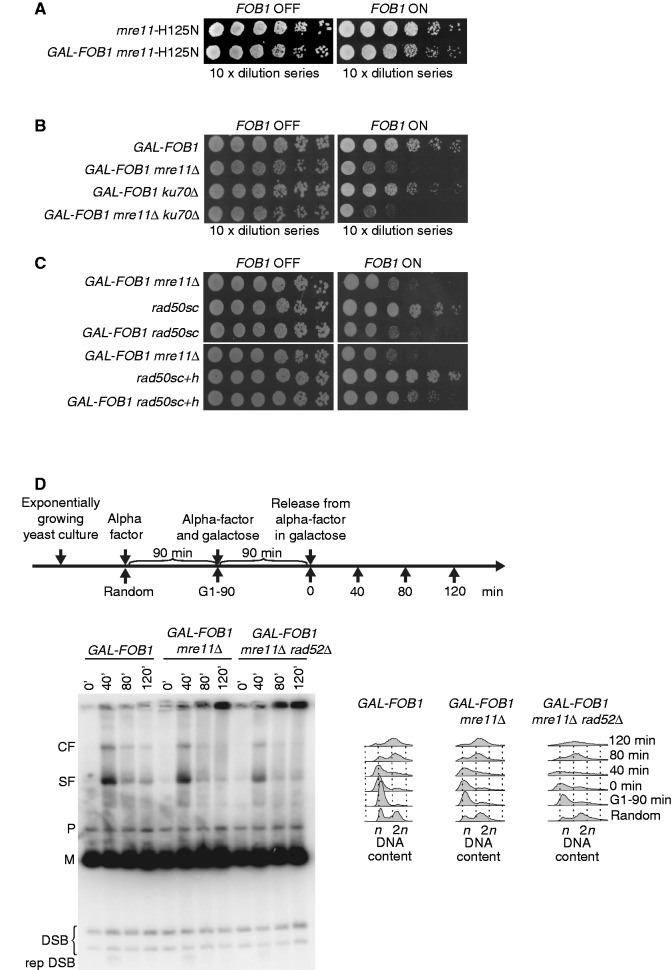

To further support this rationale, we investigated the behaviour of a well-characterized Mre11 mutant, which is endo- and exonuclease deficient (mre11-H125N), in our Fob-block system. Spot assays reveal that these enzymatic activities of Mre11 are not required for growth during conditions, where RFBs are induced (Figure 3A). We therefore rule out a function of the MRX complex in early resection. Next, an mre11Δ yku70Δ double mutant was generated in our GAL-FOB1 strain to test whether deletion of YKU70 would suppress the growth defect of an MRE11 deletion. It has previously been shown that the mre11Δ IR sensitivity is suppressed by YKU70 deletion. This is thought to originate from the loss of end protection by Ku, which then would allow DSB ends to be processed even in the absence of Mre11 (36,37). When the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ yku70Δ strain was analysed, a growth defect comparable with that of the mre11Δ single mutant was observed (Figure 3B). All together, this supports the notion that MRX accomplishes a task at RFBs, which is not directly connected with its role in DSB processing.

Figure 3.

The MRX complex plays a DSB independent role at RFBs (A) Shown are isogenic strains of mre11-H125N (LBy-623), GAL-FOB1 mre11-H125N (LBy-631). (B) Deletion of KU70 does not suppress the phenotype of GAL-FOB1 mre11 mutant. Shown are isogenic strains of GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756), GAL-FOB1 ku70Δ (LBy-905) and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ ku70Δ (LBy-903). (C) Molecular bridging is required by MRX complexes is required at protein–DNA barriers. Shown are isogenic strains of GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756), rad50sc (LBy-1061), GAL-FOB1 rad50sc (LBy-1070), rad50sc+h (LBy-1062) and GAL-FOB1 rad50sc+h (LBy-1071) (D) Absence of Mre11 does not generate more DSBs in the rDNA, but abnormal structures are detected. Shown is a DSB assay for GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756) and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ rad52Δ (LBy-680). Digested rDNA units (M), partial digested rDNA units (P), converging forks (CF), stalled forks at RFB (SF), replication independent DSBs (DSB), replication dependent DSB (rep DSB).

To establish whether the structural features intrinsic to the MRX complex is needed to cope with protein–DNA barriers, we took advantage of the rad50sc and rad50sc+h mutants. The rad50sc mutant is altered in the CXXC domain compromising hook–hook interactions, whereas the rad50sc+h mutant carries a truncated coiled-coil domain, which shortens the length of the molecular tether by 243 aa. Despite these structural alterations, the MRX complex remains intact in rad50sc and rad50sc+h mutants, and homologous recombination functions are largely unaffected in the rad50sc+h mutant (38). We coupled the two mutants with our Fob-block system and investigated growth by spot assays. The GAL-FOB1 rad50sc strain displays the same growth defect as a GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ strain on galactose, whereas the GAL-FOB1 rad50sc+h strain shows a milder but reproducible growth defect compared with the GAL-FOB1 mre11 strain (Figure 3C). Together, these data underscore the importance of the hook and coiled-coil domains of Rad50 for proper growth when protein–DNA barriers are induced, and thereby strongly points to molecular bridging being required at protein–DNA barriers.

We thus seek a function for the MRX complex, which is DSB independent, but pivotal for the cell on increased replication fork stalling in the rDNA. One such function could be as a fork stabilizer as has previously been suggested for HU-stalled forks (39). If replication forks stalled at protein–DNA barriers are unstable in the absence of a competent MRX complex, this may lead to more DSBs in the rDNA. We thus tested whether more DSBs could be scored in the rDNA in the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ strain using a DSB assay previously described (28,40). Although the majority of DSBs found for wild-type cells at the rDNA has been suggested to be a result of pre-existing nicks, which are insensitive to normal DSB repair processing (41), elevated levels of DSBs have been demonstrated in different mutants (40–42). Figure 3C shows an autoradiogram obtained with a probe recognizing a sequence located between 5S and the RFB. Consistent with previous reports, we obtain two bands in all samples, migrating below the digested rDNA units (M) and representing S-phase independent DSBs (28). Furthermore, we also detect the S-phase specific DSB at 40 min (28). Importantly, no obvious difference in the level of the DSBs are detected between GAL-FOB1 and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ cells, which suggests that absence of Mre11 does not give rise to a significant elevated level of DSBs around the RFB site in the rDNA. Even suppressing DSB repair by a RAD52 deletion (GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ rad52Δ) does not enable us to detect more DSBs in the rDNA (Figure 3C).

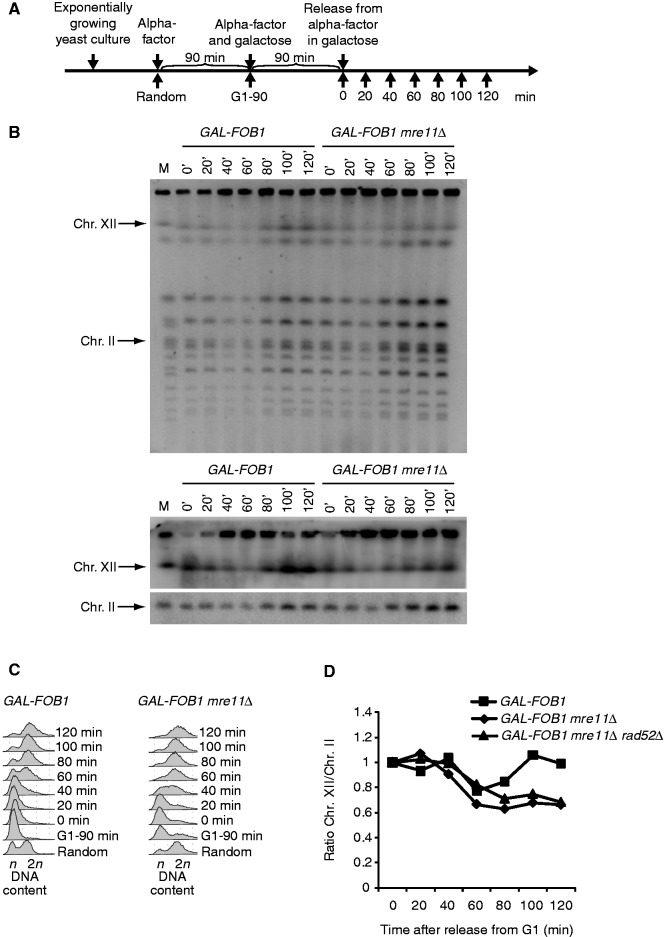

From our DSB assay, we notice an accumulation of DNA structures in the absence of Mre11, which fail to migrate into the gel at the later time points. Although replication dependent, these structures do not represent unreplicated DNA, as they are not detected during early DNA replication (40-min sample) in GAL-FOB1 and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ cells, but accumulate after bulk DNA synthesis has taken place according to FACS analyses. Furthermore, the DNA structures are formed in a recombination independent way, as retention is also observed in GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ rad52Δ cells.

To further investigate this phenomenon, we analysed genomic DNA using the well-established pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) method. In PFGs, linear DNA migrates according to its size, whereas branched structures as well as replication and recombination intermediates do not enter the gel and remain trapped in the wells. Cells were processed as schematically shown in Figure 4A, and DNA isolated in agarose plugs was analysed by PFGE. Figure 4B shows an EtBr stain of the PFG as well as a Southern blot obtained with probes recognizing Chr. XII and Chr. II. From this, it is evident that Chr. XII fails to fully enter the gel after bulk DNA synthesis has occurred in the absence of MRE11 (as evident from FACS analysis presented in Figure 4C). Quantification of the Southern blot reveals that ∼40% of Chr. XII remains in the wells in the absence of MRE11 (Figure 4D). This suggests that either branched structures, replication intermediates or recombination intermediates are frequently formed in GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ. As GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ rad52Δ cells still retain DNA in the wells, we can conclude that the retained structure is not a true recombination intermediate (only quantification is shown for GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ rad52Δ in Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Chr. XII partly fails to migrate into the gel in a Fob-block mre11Δ strain. (A) Outline of yeast culture treatment before PFGE analysis. (B) Shown are PFGE analysis for GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413) and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756) cells. The upper panel shows ethidium bromide staining of gel, and the lower panel shows Southern blotting of the same gel with probes recognizing Chr. XII and Chr. II, respectively. (C) FACS analysis on samples taken for PFGE analysis. (D) Quantification of the amount of Chr. XII entering the gel relative to Chr. II. Included is also quantification done for the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δrad52Δ strain (LBy-680). See ‘Material and Methods’ section for further details.

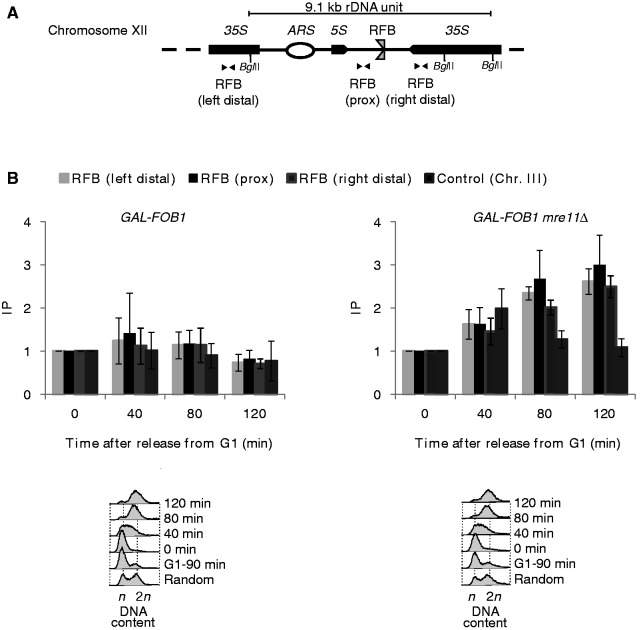

To investigate whether the retained structure contains any ssDNA, we performed ChIP using anti-Rfa1 antibody. Extensive levels of ssDNA may inhibit proper restriction digestion in our DSB assay, which could explain why DNA is retained in the wells in this assay. ChIP experiments were performed with the GAL-FOB1 and the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ strains, where the experimental setup was as schematically shown in Figure 3C. Recovered DNA was analysed using three primer sets located in close proximity to the RFB sequence in the rDNA (Figure 5A). During S–phase, there is a slight increase in recovered RPA for both strains (Figure 5B, 40-min timepoint). Oppose to the GAL-FOB1 strain, where recovered RPA decreases at the late time points of the experiments absence of Mre11 leads to an accumulation of RPA in late S-G2 phase. Thus, we recover a 2–3-fold increase of RPA in proximity to the RFB 80 and 120 min after release of cells into the S phase (Figure 5B). As we do not recover RPA above background at Chr. III in GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ, our data suggest that the structures accumulating in the rDNA in the absence of Mre11 includes RPA coated ssDNA. Increased levels of ssDNA in the rDNA are not intrinsic to lack of Mre11, as an mre11Δ strain does not give rise to more ssDNA compared with the GAL-FOB1 strain relative to the GAL-FOB1 strain (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 5.

RPA accumulates on replication fork stalling at the RFB in the rDNA. (A) Schematic illustration of a single rDNA unit with the positions of the primers used for real-time PCR shown (B) ChIP was performed using antibody against RPA (Rfa1) on synchronized cells from GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413) and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756) strains. Time (min) after release from alpha-factor block is indicated below each graph. Regions in near proximity to the RFB site [(RFB (prox)] and distal to the RFB site [RFB (right distal) and RFB (left distal)] were amplified by real-time PCR. Enrichment of RPA around the RFB site was plotted as fold increase of immunoprecipitated DNA over beads alone. Fold increase of time point 0 sample was set at 1. Error bars, s.d. (n = 3). A representative FACS profile for GAL-FOB1 (LBy-475) and GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-545) are shown (lower panel). n and 2 n are DNA content in G1 and G2, respectively.

In summary, we discover an endo- and exonuclease independent role for the MRX complex for DNA integrity at RFBs, where absence of MRX leads to an accumulation of DNA structures at the rDNA after bulk DNA synthesis, which are retained in the wells in a PFG. Furthermore, lack of MRX results in a higher level of RPA binding in the rDNA, which suggests that the retained DNA structure contains regions of ssDNA.

Ectopically placed RFBs but not RFBs in the rDNA trigger a checkpoint response in the absence of MRX

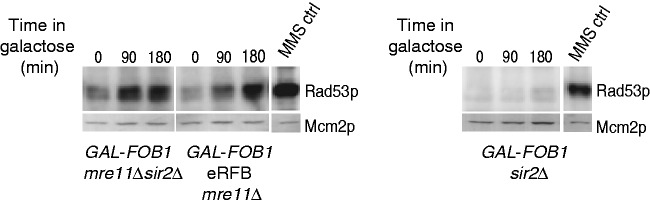

To test whether the higher levels of ssDNA observed in the absence of the MRX complex activate a checkpoint response, Rad53 activation was investigated using the in situ autophosphorylation assay (ISA) (26).

Rad53 activation was first investigated in the GAL-FOB1 strain. Cells were grown as shown schematically in Figure 6A. In accordance with our spot assays, where normal growth on galactose is observed, we do not detect any Rad53 activation in this strain (Figure 6B). Next, GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ was tested. To our surprise, we failed to detect Rad53 activation in the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ strain (Figure 6C), which could indicate that either the amount of ssDNA accumulating in the absence of Mre11 is not sufficient to trigger a checkpoint response or alternatively, checkpoint activation is suppressed in this chromosomal context.

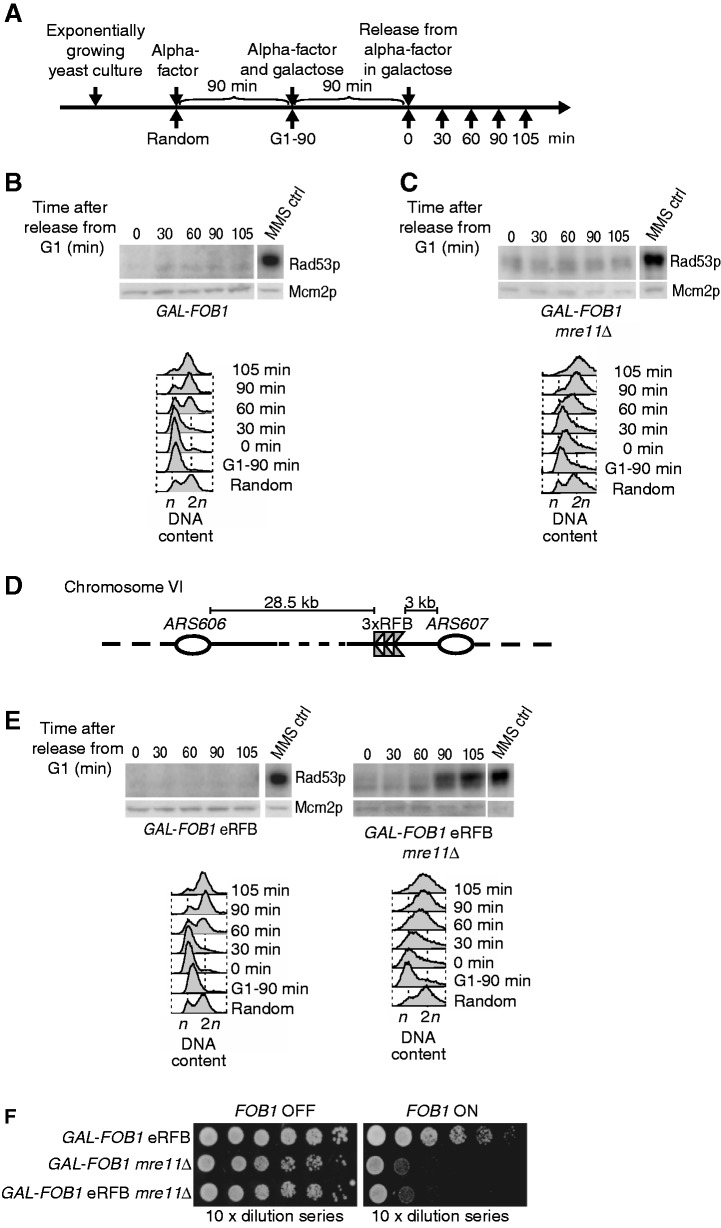

Figure 6.

Ectopically placed RFBs but not RFBs in the rDNA trigger a checkpoint response in the absence of Mre11. (A) Outline of yeast culture treatment preceding ISA. (B) The GAL-FOB1 (LBy-413) strain does not trigger checkpoint activation on induction of protein–DNA barriers. (C) A checkpoint response is not activated, despite growth problems and RPA accumulation in the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ strain (LBy-756). (D) Schematic representation of the modified Fob-block system at Chr. VI with ectopic RFBs inserted close to ARS607. (E) Absence of MRE11 leads to checkpoint activation when active protein–DNA barriers are present ectopically on Chr. VI in the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain (LBy-649). Checkpoint activation was also investigted for a GAL-FOB1 eRFB strain (LBy-439). For all kinase assays shown, equal amount of yeast extract was loaded on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels. For each strain, the upper box shows the incorporation of [γ-32P] adenosine triphosphate into Rad53p and the bottom panel a western for Mcm2p on the same blot. Time (min) after release from alpha-factor block is indicated above each gel. MMS control (ctrl) is 5 µl of a sample containing a fixed amount of MMS-activated Rad53p standard, which is used for internal control of the kinase assays and allows comparison between gels. Samples shown together and with the same MMS ctrl have been loaded on the same gel. FACS samples were taken throughout the experiments and cell cycle profile displayed below each gel. (F) Spot assays performed as in Figure 2 for the isogenic strains GAL-FOB1 eRFB (LBy-439), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ (LBy-756), GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ (LBy-649).

To differentiate between these options, we set out to investigate whether a checkpoint can be provoked if RFBs are inserted in another chromosomal context. We contructed a strain with a triplicate of RFB sequences inserted ectopically in a non-transcribed region on chromosome VI between the early firing origins ARS606 and ARS607 (GAL-FOB1 eRFB where e denotes ectopically). We chose this chromosomal locus, as we have previously used this to study responses to a single protein–DNA adduct (21). The rationale behind insertion of RFB triplicates and not only a single RFB sequence at this locus was to increase the percentage of cells in a culture with active RFBs (we still only expect binding of one Fob1 owing to constrain). Checkpoint activation was next investigated in two strains, GAL-FOB1 eRFB and GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ. As expected, the GAL-FOB1 eRFB did not give rise to checkpoint activation (Figure 6E), whereas we obtain robust Rad53 activation, when Mre11 is absent. Checkpoint activation is detectable in the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain at 90 min after release from the G1 arrest, giving more robust signals 105 min after release, which coincides with the late S/G2 phase of the cell cycle as revealed from FACS analysis (Figure 6E). Although the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain has activated checkpoint, this does not influence cell growth, as the scored growth defect for this strain is comparable with that observed for the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ strain (Figure 6F).

Although we do not expect that several Fob proteins are able to bind at these triplicates owing to constrain in the amount of base pairs available for wrapping around the Fob1 protein, we confirmed that the checkpoint activation observed for the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ was not due to increased ‘strength’ of the ectopic protein–DNA barrier relative to those in the rDNA compartment. Thus, checkpoint activation was investigated in a strain where only one RFB sequence was inserted between ARS606 and ARS607. As evident from Supplementary Figure S2, absence of MRE11 in this strain leads to a robust checkpoint activation much alike what was observed for the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain (Figure 6E). Thus, checkpoint activation in the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain cannot be explained by a difference in RFB strength. Furthermore, to rule out that homologous recombination is required at ectopic RFBs owing to different processing compared with RFBs in the rDNA, and thus could explain the difference in checkpoint activation, we generated a GAL-FOB1 eRFB rad52Δ mutant and investigated growth. These spot assays confirm that Rad52 is not required for cells to overcome an ectopic protein–DNA barrier, and thus in this respect, there is no difference between ectopic RFBs and RFBs in the rDNA (Supplementary Figure S3).

Taken together, the results demonstrate that absence of MRX leads to robust checkpoint activation when ectopically placed RFBs are present; on the contrary, although RPA-containing DNA is present at the rDNA, this fails to induce a detectable checkpoint response.

From the previous analysis, we do not know whether the ARS606–ARS607 region is fully replicated. If the MRX complex is a general replication fork stabilizer, the rightward-moving fork (coming from ARS606) may encounter problems in the absence of the MRX complex. Thus, we cannot rule out that the observed checkpoint activation is merely due to problems in the ARS606–ARS607 region rather than problems arising directly at the ectopically placed RFB in the absence of the MRX complex. To investigate the fate of the rightward-moving fork, we entertained the idea that if this fork encounters problems, it would lead to either delayed replication or unreplicated DNA in the ARS606–ARS607 region.

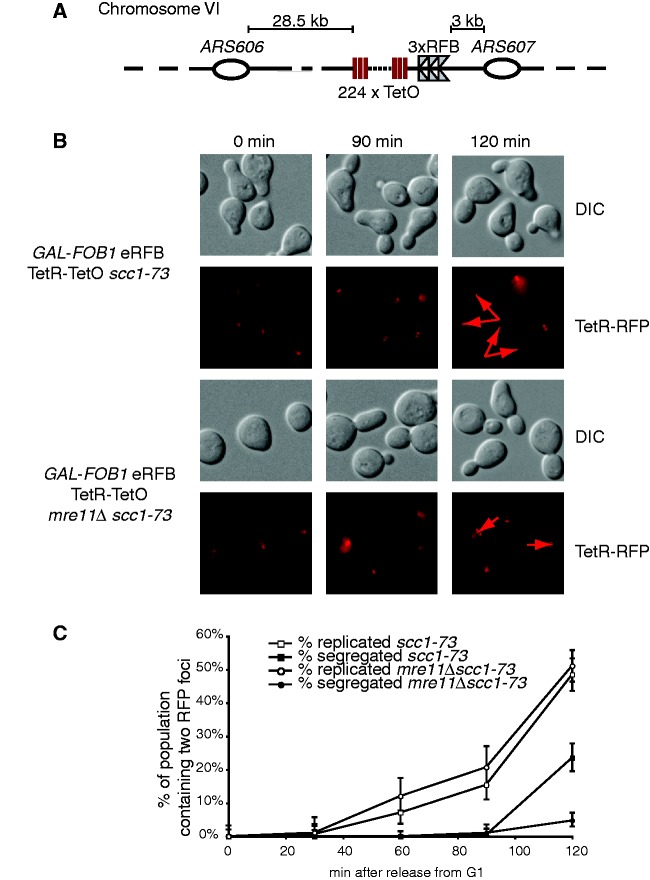

Fluorescence microscopy was used to study the potential presence of unreplicated DNA in near proximity to the RFBs at Chr. VI. A TetO array was inserted in the ARS606–ARS607 region close to the RFBs in GAL-FOB1 eRFB and GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strains (Figure 7A). We anticipated that a single Tet repressor (TetR)-RFP focus would exist in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, whereas two foci would be present in late S/G2 phase of the cell cycle in the case of normal replication of the region. To be able to score two dots independently of the segregation event, we combined our GAL-FOB1 eRFB TetR-TetO and GAL-FOB1 eRFB TetR-TetO mre11Δ strains with a ts allele of SCC1 (scc1-73), which at 34°C will result in sister chromatid cohesion failure (43). This will allow us to detect two dots before actual segregation due to ‘breathing’ of the sister chromatids. Cells were synchronized in G1, and Fob1 induced to activate the RFB, whereas Scc1 was inactivated at 34°C, before cells were released into S-phase at 34°C to keep Scc1 inactivated. At the indicated times, cells were analysed by fluorescence microscopy to score the presence of one or two (TetR)-RFP dots (Figure 7B). Two dots are seen in the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain, revealing that replication takes place in the ARS606–ARS607 region. As shown graphically, there is no difference in the timing of appearance of two dots in the two strains, and the percentage of cells with the locus replicated is also the same (Figure 7C). However, absence of MRE11 leads to a significant delay in the segregation process, which may be explained by the basal level of checkpoint activation, which we always detect for mre11Δ cells. Alternatively, the accumulation of late replication intermediates or branched structures we observed in the absence of MRE11 in our Fob-block system could also account for this delayed segregation.

Figure 7.

Checkpoint activation is a direct cause of the ectopically placed RFB (A) Schematic representation of the modified Fob-block system with a TetO-array. (B) The ARS606–ARS607 region is fully replicated as measured by fluorescence microscopy on strain GAL-FOB1 eRFB TetR-TetO scc1-73 (LBy-868) and GAL-FOB1 eRFB TetR-TetO mre11Δ scc1-73 (LBy-880). Fluorescence (TetR-RFP) and differential interference contrast images (DIC) of representive cells. Arrowheads mark foci. (C) Quantification of cells containing two RFB foci and of cells with segregated foci. At each time point, 100–300 cells were examined for RFB foci.

As we fail to detect unreplicated DNA in the ARS606–ARS607 region, we conclude that the rightward-moving fork is replication competent throughout this region. Thus, neither problems for the active fork nor unreplicated DNA is the checkpoint-causing event. Instead our data strongly suggest that it is an incidence directly at the ectopic RFBs, which generates the checkpoint-activating structure in the absence of the MRX complex. Thus, problems at a protein–DNA barrier at its natural cellular chromosomal context do not generate a detectable checkpoint signal, whereas placed ectopically, it causes a robust checkpoint-activating signal.

Chromatin context dictates checkpoint activation

The aforementioned data suggest that chromosomal context may have an influence on checkpoint signalling. Induction of the Fob-block system will likely affect the level of rDNA silencing, as more Sir2 will be recruited to the RFBs via the regulator of nucleolar silencing and telophase exit complex (29,30). Although we find that a SIR2 deletion does not rescue the slow growth phenotype of an MRE11 deletion in our Fob-block system, we cannot rule out that a higher level of rDNA silencing may affect the checkpoint response. To examine this, we investigated Rad53 activation in a GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ sir2Δ strain. This experiment was conducted with asynchronous yeast cultures, as sir2Δ strains are insensitive to alpha factor treatment. Samples were taken before galactose induction and after 90 and 180 min of induction. As a positive control for this experiment, we included the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain, and checkpoint activation was also investigated in a GAL-FOB1 sir2Δ strain. Excitingly, Rad53p activation now occurs in the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ sir2Δ strain to approximately the same level as seen for the GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strain, whereas deletion of sir2Δ alone in the GAL-FOB1 strain does not give rise to checkpoint activation (Figure 8). We cannot rule out that more DSBs are generated in the GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ sir2Δ cells, and that this is the checkpoint-causing event. Indeed, a triple mutant GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ sir2Δ rad52Δ is extremely slow growing compared with any of the double mutant combinations, which demonstrates a requirement for homologous recombination when both Mre11 and Sir2 are absent (data not shown). This slow growth is, however, totally independent on FOB1 induction opposed to the observed checkpoint activation, which requires FOB1 induction. Thus, checkpoint activation is caused by events, which are triggered by a protein–DNA barrier.

Figure 8.

Sir2 suppresses the checkpoint response in the rDNA. ISA was performed on asynchronous yeast cultures of GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ (LBy-649), GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ sir2Δ (LBy-909) and GAL-FOB1 sir2Δ (LBy-888) strains. Samples were taken before galactose induction and after 90 and 180 min of induction. The kinase assay was performed as described in ‘Material and Methods’ section and in Figure 6.

In summary, our results demonstrate that by alleviating Sir2-mediated rDNA silencing, cells are now able to provoke a checkpoint response from within the rDNA when the MRX complex is absent. The results suggest that rDNA silencing not only controls recombination but also suppresses proper checkpoint response at least in the vicinity of the RFB.

DISCUSSION

Our study reveals several novel observations. First, we uncover a DSB-independent function of the MRX complex for DNA integrity at protein–DNA barriers in the rDNA, where absence of the MRX complex leads to increased levels of ssDNA. Second, we find that absence of Mre11 does not trigger a checkpoint response from within the rDNA, whereas its absence leads to checkpoint activation when ectopically placed RFBs are present. Third, relieving rDNA silencing is sufficient to provoke checkpoint activation in the rDNA to the same extent as seen for the ectopic site, strongly suggesting that checkpoint activation is governed by chromatin context at least in the rDNA.

In our Fob-block system, all events caused by higher levels of stalled replication forks in the rDNA are unproblematic for wild-type cells but become detrimental when cells lack MRX. This is in agreement with genetic data reporting that absence of Rrm3, a helicase required for helping replication forks traverse protein–DNA barriers, leads to synthetic lethality with mre11Δ, rad50Δ and xrs2Δ (44). Although overexpression of Fob1 likely affects the level of rDNA, silencing deletion of SIR2 does not suppress the growth defect observed in the absence of the MRX complex. This supports the idea that the MRX complex is required at the rDNA owing to replication fork stalling and not owing to an affected rDNA silencing on overexpression of Fob1.

We provide evidence for a DSB independent role of MRX at protein–DNA barriers based on three facts. First, RAD52 is not required for proper cell growth in our Fob-block system, which argues against DSB formation. Second, the growth defect observed for GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ cells is not suppressed by a YKU70 deletion. It has previously been reported that suppression of mre11Δ phenotypes by a YKU70 deletion is restricted to events at DSB ends (37). Third, the endo- and exonuclease activities of Mre11p are not required.

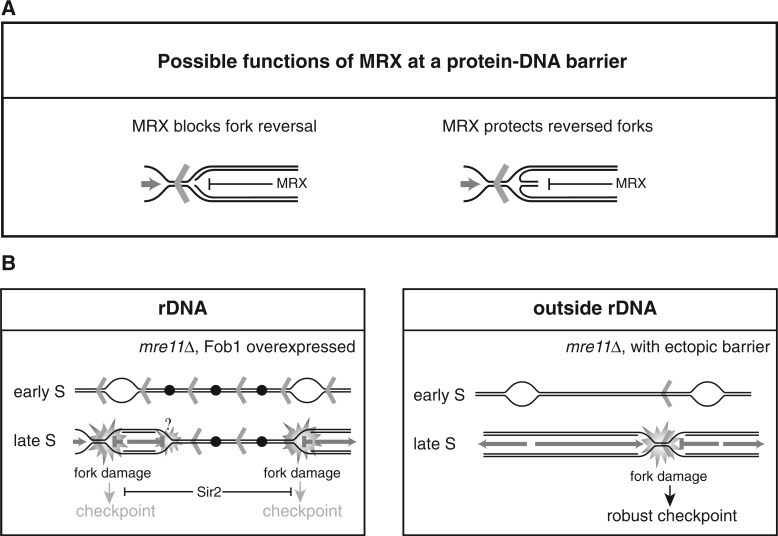

At present, we do not know the exact mechanism by which MRX protects forks at RFBs; however, several modes of action can be envisioned, which are not mutually exclusive. MRX may preserve the conformation of newly synthesized DNA behind forks at RFBs, thus preventing replisome collapse. This function would be analogous to what has been suggested for MRX at HU-stalled forks and is supported by structural data showing that the MRX complex can bridge two DNA duplexes held in the same distance as newly synthesized sister chromatids (39,45). Alternatively, the MRX complex may prevent fork reversal at RFBs (Figure 9A). At so-called terminal forks, absence of the Mre11 has been suggested to lead to fork reversal, where the generated structure is prone to cleavage (46). If fork reversal occurs at RFBs in the absence of Mre11, it does not seem to be prone to cleavage, as we fail to detect higher levels of DSBs at the RFBs in the rDNA. However, our PFGE analysis supports the idea that absence of the MRX complex could lead to more branched structures in the rDNA, as a large portion of Chr. XII is retained in the wells. The retention of DNA in the wells in the DSB assays more likely stems from an inhibition of restriction enzyme digestion owing to the presence of ssDNA, as branched structures will run into this type of gel. Furthermore, we detect more RPA in the rDNA at late time points (after bulk DNA synthesis) in the absence of Mre11. This indicates that processing occurs in these cells generating more ssDNA compared with wild-type cells. This can be explained if more reversed forks are generated in the absence of MRX, which are processed to give ssDNA. Indeed, regions of ssDNA are frequently detected on the regressed arm of a reversed fork (47). It has been suggested that reversed forks are formed in yeast cells at RFBs in the rDNA (48), and there are accumulating evidence that stalled replication forks are very prone to fork reversal (47,49–51). If fork reversal is a frequent incidence at RFBs even in wild-type cells, it is attractive to think of the MRX complex as a ‘protector’ of the structure (Figure 9A). On fork reversal, a double-stranded end is exposed, which can be recognized by the MRX complex. Binding of the MRX complex to this end could potentially protect the structure from further processing. Our ChIP data would also be consistent with this hypothesis.

Figure 9.

(A) Suggested functions of the MRX complex on replication fork stalling at a protein–DNA barrier. The MRX complex may hinder fork reversal (left) or protect a reversed fork from further processing (right). (B) Model for the cellular consequences to elevated levels of replication fork stalling in the rDNA (left panel), and for ectopically placed RFBs (right panel) in mre11Δ cells. Fob1 induction generates a higher level of active RFBs in the rDNA, which have detrimental effect on growth when the MRX complex is absent. The growth defect may stem from problems arising directly at the RFBs; however, as replication in the rDNA is challenged by its repetitive nature where unusual structures have the potential to form, fork stalling at other places than the RFB may be a frequent event. Together, this creates a strong need for the MRX complex either to suppress fork reversal or protect reversed forks in the rDNA. When the RFB sequence is placed ectopically, the MRX complex is required at the protein–DNA barrier as the rightward-moving fork is replication competent throughout the ARS606–ARS607 region. Aberrant structures generated in the absence of the MRX complex are checkpoint blind in the rDNA owing to the presence of Sir2, whereas ectopically placed RFBs provoke a checkpoint signal in the absence of the MRX complex. Open bubbles represent active origins, whereas black dots represent inactive origins. Red arrowheads represent Fob1-bound RFB sequences.

The observed growth defect is identical for GAL-FOB1 mre11Δ and GAL-FOB1 eRFB mre11Δ strains. Thus, the ectopically RFBs do not contribute additionally to a growth defect. It is tempting to believe that the growth defect stems from problems arising directly at the RFBs, but we cannot rule out that it originates owing to other problems in the rDNA. Replication in the rDNA is not only challenged by the unidirectional mode of replication but also owing to its repetitive nature, unusual secondary structures that may affect DNA replication (e.g. creating more stalling) are also more likely to be generated in this region. Together, this would create a stronger need for the MRX complex in this region either to suppress fork reversal or protect a reversed fork. Thus, we cannot exclude that the rightward-moving fork in the rDNA encounters problems in the absence of the MRX complex, although this is not the case for the rightward-moving fork in the ARS606–ARS607 region (Figure 7).

The cellular implications in the rDNA on FOB1 induction and in the absence of Mre11 are to our surprise checkpoint blind (Figure 8B), which is in striking contrast to the checkpoint activation arising when forks stall at ectopically placed barriers in the absence of Mre11 (Figure 9B). We believe that it is a structure arising at the ectopic barrier, which is checkpoint activating, as we fail to detect unreplicated DNA in this region, supporting that a fully competent fork emanates from ARS606. Opposed to the rDNA and to our surprise, we fail to detect more RPA at this location; however, this is probably due to limitations in our ChIP experiments.

Why is it that abnormal structures at ectopically placed RFBs are checkpoint activating but checkpoint blind in the rDNA? It has been shown that a DSB induced in the rDNA by the endonuclease I-SceI is checkpoint activating; thus, the unique heterochromatic structure found in the rDNA is not enough to suppress a checkpoint response under normal circumstances (52). Furthermore, we can rule out a general function of Mre11 for checkpoint activation in the rDNA, as we can detect checkpoint activation when a DSB is induced by the endonuclease I-SceI in the absence of Mrell (Supplementary Figure S4). However, we considered the idea that overexpression of Fob1 in our Fob-block system could lead to a significant higher level of heterochromatic structure in the rDNA, which may impact checkpoint activation. Indeed, when SIR2 is deleted, we are able to detect Rad53 activation to the same level as seen in strains with ectopically placed RFBs. Thus, disturbance of a balanced rDNA silencing may adversely affect the checkpoint response. This effect may be direct in that the heterochromatic structure hinders access of checkpoint sensors and thereby suppress the checkpoint response. However, it is also easy to imagine that unbalanced rDNA silencing encumbers proper processing of the DNA at the RFBs into a strong checkpoint activating structure. Another attractive possibility is that SIR2 in general suppresses checkpoint in the vicinity of RFBs.

Our finding that a SIR2 deletion restores checkpoint activation points to a significant influence of chromatin structure on checkpoint activation in the rDNA. In line with this, it has been reported that heterochromatin could pose a barrier to the DNA damage response pathway (53–57), and more recent, it was furthermore shown that heterochromatin induced by oncogenic stress restrains DNA damage response (58).

It is reasonable to picture that there is a delicate balance in the rDNA to know whether a checkpoint response is activated. In the Rdna, both replication dependent and independent double strand breaks occur in each cell cycle, which are not checkpoint activating (41), whereas an I-SceI generated DSB causes checkpoint activation [Supplementary Figure S3 and (52)]. Thus, in the rDNA, there may be an inherent way to distinguish between natural or aberrant damage. Alternatively, as RFBs are a natural integrated part of the rDNA, and a hotspot for DSBs, it is attractive to suggest that Sir2 in general suppresses checkpoint activation in the vicinity of the RFBs. Future studies will hopefully uncover the underlying mechanism controlling this phenomenon and unravel whether this is evolutionarily conserved.

SUPPLEMENTRY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1–3, Supplementary Figures 1–4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary reference [59]

FUNDING

Danish Research Counsil [FNU 21-04-0354, FNU 272-07-0366]; Aase og Einar Danielsens Foundation; Augustinus Foundation and Dagmar Marshall Foundation (to L.B.), the Danish Cancer Society (to A.H.A. and L.B.). The Lundbeckfoundation (53/06) (to I.B.B.); the Villum Kann Rasmussen Foundation and the European Research Council (to M.L.). Funding for open access charge: Augustinus Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank F. Uhlmann for the gift of ssc1-73 strain and L. Symington for the mre11-H125N allele, and J. Petrini for the Rad50 mutant strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Admire A, Shanks L, Danzl N, Wang M, Weier U, Stevens W, Hunt E, Weinert T. Cycles of chromosome instability are associated with a fragile site and are increased by defects in DNA replication and checkpoint controls in yeast. Genes Dev. 2006;20:159–173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1392506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glover TW. Common fragile sites. Cancer Lett. 2006;232:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert S, Carr AM. Checkpoint responses to replication fork barriers. Biochimie. 2005;87:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tourriere H, Pasero P. Maintenance of fork integrity at damaged DNA and natural pause sites. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2007;6:900–913. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewer BJ, Lockshon D, Fangman WL. The arrest of replication forks in the rDNA of yeast occurs independently of transcription. Cell. 1992;71:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90355-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi T. Regulation of ribosomal RNA gene copy number and its role in modulating genome integrity and evolutionary adaptability in yeast. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:1395–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0613-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalgaard JZ, Klar AJ. swi1 and swi3 perform imprinting, pausing, and termination of DNA replication in S. pombe. Cell. 2000;102:745–751. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katou Y, Kanoh Y, Bando M, Noguchi H, Tanaka H, Ashikari T, Sugimoto K, Shirahige K. S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature. 2003;424:1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature01900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desany BA, Alcasabas AA, Bachant JB, Elledge SJ. Recovery from DNA replicational stress is the essential function of the S-phase checkpoint pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2956–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobb JA, Bjergbaek L, Shimada K, Frei C, Gasser SM. DNA polymerase stabilization at stalled replication forks requires Mec1 and the RecQ helicase Sgs1. EMBO J. 2003;22:4325–4336. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Newlon CS, Foiani M. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tercero JA, Longhese MP, Diffley JF. A central role for DNA replication forks in checkpoint activation and response. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1323–1336. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tercero JA, Diffley JF. Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature. 2001;412:553–557. doi: 10.1038/35087607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calzada A, Hodgson B, Kanemaki M, Bueno A, Labib K. Molecular anatomy and regulation of a stable replisome at a paused eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1905–1919. doi: 10.1101/gad.337205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert S, Watson A, Sheedy DM, Martin B, Carr AM. Gross chromosomal rearrangements and elevated recombination at an inducible site-specific replication fork barrier. Cell. 2005;121:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn JS, Osman F, Whitby MC. Replication fork blockage by RTS1 at an ectopic site promotes recombination in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2005;24:2011–2023. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bidnenko V, Ehrlich SD, Michel B. Replication fork collapse at replication terminator sequences. EMBO J. 2002;21:3898–3907. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courcelle J, Donaldson JR, Chow KH, Courcelle CT. DNA damage-induced replication fork regression and processing in Escherichia coli. Science. 2003;299:1064–1067. doi: 10.1126/science.1081328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert S, Mizuno K, Blaisonneau J, Martineau S, Chanet R, Freon K, Murray JM, Carr AM, Baldacci G. Homologous recombination restarts blocked replication forks at the expense of genome rearrangements by template exchange. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuno K, Lambert S, Baldacci G, Murray JM, Carr AM. Nearby inverted repeats fuse to generate acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosomes by a replication template exchange mechanism. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2876–2886. doi: 10.1101/gad.1863009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen I, Bentsen IB, Lisby M, Hansen S, Mundbjerg K, Andersen AH, Bjergbaek L. A Flp-nick system to study repair of a single protein-bound nick in vivo. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:753–757. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frei C, Gasser SM. The yeast Sgs1p helicase acts upstream of Rad53p in the DNA replication checkpoint and colocalizes with Rad53p in S-phase-specific foci. Genes Dev. 2000;14:81–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu JR, Gilbert DM. Rapid DNA preparation for 2D gel analysis of replication intermediates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3997–3998. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.19.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huberman JA, Spotila LD, Nawotka KA, el-Assouli SM, Davis LR. The in vivo replication origin of the yeast 2 microns plasmid. Cell. 1987;51:473–481. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maringele L, Lydall D. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of budding yeast chromosomes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;313:65–73. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellicioli A, Lucca C, Liberi G, Marini F, Lopes M, Plevani P, Romano A, Di Fiore PP, Foiani M. Activation of Rad53 kinase in response to DNA damage and its effect in modulating phosphorylation of the lagging strand DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 1999;18:6561–6572. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou H, Rothstein R. Holliday junctions accumulate in replication mutants via a RecA homolog-independent mechanism. Cell. 1997;90:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkhalter MD, Sogo JM. rDNA enhancer affects replication initiation and mitotic recombination: Fob1 mediates nucleolytic processing independently of replication. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straight AF, Shou W, Dowd GJ, Turck CW, Deshaies RJ, Johnson AD, Moazed D. Net1, a Sir2-associated nucleolar protein required for rDNA silencing and nucleolar integrity. Cell. 1999;97:245–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Moazed D. Association of the RENT complex with nontranscribed and coding regions of rDNA and a regional requirement for the replication fork block protein Fob1 in rDNA silencing. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2162–2176. doi: 10.1101/gad.1108403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shim EY, Chung WH, Nicolette ML, Zhang Y, Davis M, Zhu Z, Paull TT, Ira G, Lee SE. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 2010;29:3370–3380. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cejka P, Cannavo E, Polaczek P, Masuda-Sasa T, Pokharel S, Campbell JL, Kowalczykowski SC. DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature. 2010;467:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature09355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niu H, Chung WH, Zhu Z, Kwon Y, Zhao W, Chi P, Prakash R, Seong C, Liu D, Lu L, et al. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2010;467:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature09318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bressan DA, Baxter BK, Petrini JH. The Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 protein complex facilitates homologous recombination-based double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:7681–7687. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 2010;29:3358–3369. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hohl M, Kwon Y, Galvan SM, Xue X, Tous C, Aguilera A, Sung P, Petrini JH. The Rad50 coiled-coil domain is indispensable for Mre11 complex functions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:1124–1131. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tittel-Elmer M, Alabert C, Pasero P, Cobb JA. The MRX complex stabilizes the replisome independently of the S phase checkpoint during replication stress. EMBO J. 2009;28:1142–1156. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weitao T, Budd M, Hoopes LL, Campbell JL. Dna2 helicase/nuclease causes replicative fork stalling and double-strand breaks in the ribosomal DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22513–22522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritsch O, Burkhalter MD, Kais S, Sogo JM, Schar P. DNA ligase 4 stabilizes the ribosomal DNA array upon fork collapse at the replication fork barrier. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2010;9:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weitao T, Budd M, Campbell JL. Evidence that yeast SGS1, DNA2, SRS2, and FOB1 interact to maintain rDNA stability. Mutat. Res. 2003;532:157–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K. Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1. Nature. 1999;400:37–42. doi: 10.1038/21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torres JZ, Schnakenberg SL, Zakian VA. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rrm3p DNA helicase promotes genome integrity by preventing replication fork stalling: viability of rrm3 cells requires the intra-S-phase checkpoint and fork restart activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:3198–3212. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3198-3212.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hopfner KP, Craig L, Moncalian G, Zinkel RA, Usui T, Owen BA, Karcher A, Henderson B, Bodmer JL, McMurray CT, et al. The Rad50 zinc-hook is a structure joining Mre11 complexes in DNA recombination and repair. Nature. 2002;418:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doksani Y, Bermejo R, Fiorani S, Haber JE, Foiani M. Replicon dynamics, dormant origin firing, and terminal fork integrity after double-strand break formation. Cell. 2009;137:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ray Chaudhuri A, Hashimoto Y, Herrador R, Neelsen KJ, Fachinetti D, Bermejo R, Cocito A, Costanzo V, Lopes M. Topoisomerase I poisoning results in PARP-mediated replication fork reversal. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:417–423. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Defossez PA, Prusty R, Kaeberlein M, Lin SJ, Ferrigno P, Silver PA, Keil RL, Guarente L. Elimination of replication block protein Fob1 extends the life span of yeast mother cells. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:447–455. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atkinson J, McGlynn P. Replication fork reversal and the maintenance of genome stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3475–3492. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Postow L, Crisona NJ, Peter BJ, Hardy CD, Cozzarelli NR. Topological challenges to DNA replication: conformations at the fork. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8219–8226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111006998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Postow L, Ullsperger C, Keller RW, Bustamante C, Vologodskii AV, Cozzarelli NR. Positive torsional strain causes the formation of a four-way junction at replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2790–2796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torres-Rosell J, De Piccoli G, Cordon-Preciado V, Farmer S, Jarmuz A, Machin F, Pasero P, Lisby M, Haber JE, Aragon L. Anaphase onset before complete DNA replication with intact checkpoint responses. Science. 2007;315:1411–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.1134025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodarzi AA, Noon AT, Deckbar D, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Lobrich M, Jeggo PA. ATM signaling facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks associated with heterochromatin. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JA, Kruhlak M, Dotiwala F, Nussenzweig A, Haber JE. Heterochromatin is refractory to gamma-H2AX modification in yeast and mammals. J. Cell Biol. 2007;178:209–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murga M, Jaco I, Fan Y, Soria R, Martinez-Pastor B, Cuadrado M, Yang SM, Blasco MA, Skoultchi AI, Fernandez-Capetillo O. Global chromatin compaction limits the strength of the DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 2007;178:1101–1108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noon AT, Shibata A, Rief N, Lobrich M, Stewart GS, Jeggo PA, Goodarzi AA. 53BP1-dependent robust localized KAP-1 phosphorylation is essential for heterochromatic DNA double-strand break repair. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:177–184. doi: 10.1038/ncb2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziv Y, Bielopolski D, Galanty Y, Lukas C, Taya Y, Schultz DC, Lukas J, Bekker-Jensen S, Bartek J, Shiloh Y. Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double–strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:870–876. doi: 10.1038/ncb1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Di Micco R, Sulli G, Dobreva M, Liontos M, Botrugno OA, Gargiulo G, dal Zuffo R, Matti V, d'Ario G, Montani E, et al. Interplay between oncogene-induced DNA damage response and heterochromatin in senescence and cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:292–302. doi: 10.1038/ncb2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lisby M, Rothstein R. Differential regulation of the cellular response to DNA double strand breaks in G1. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.